IV. Gaza: Abuses against Fatah

Hamas’s takeover of the Gaza Strip in June 2007 was violent and swift. In eight days Hamas forces seized control of all security facilities and main government offices throughout the territory. One hundred and sixty-one Palestinians died in the fighting, including 41 civilians, and at least 700 were wounded, according to the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights.104 Both Fatah and Hamas forces committed serious violations of international humanitarian and human rights law, including summary executions and torture. Human Rights Watch is unaware of any investigations or prosecutions in Gaza against Hamas members who committed crimes.

When the fighting ended, Hamas faced the monumental task of governing Gaza—a task for which it was ill-prepared, despite one year in the government. Traditionally focused on social programs and fighting the Israeli occupation, Hamas had to govern 1.4 million people after devastating internal clashes, ongoing military pressure from Israel and intensified economic pressure from Israel, the US, the EU and other donors.

The first matter of business was to consolidate control, and Hamas went about it with scant regard for the law. Hamas’s armed wing, the ‘Izz-al-Din al-Qassam Brigades, commanded by Ahmad Jabari, and its internal police, the Executive Force, commanded by Jamal al-Jarrah (aka Abu Obaidah), arrested hundreds of Fatah leaders, activists and supporters, especially those suspected of using or possessing weapons, and held many of them in unauthorized detention facilities. Torture and beatings were common, and one man is known to have died in custody during this time.105 Hamas forces blocked demonstrations or public meetings by Fatah, and used violence to break up gatherings that did take place. They closed media outlets run by or sympathetic to Fatah.106

The next step was to reorganize the security forces. After the Hamas takeover, President Abbas ordered all members of the official security forces in Gaza to stop reporting for work if they wanted to get paid. Eager to receive their salaries, many security force members left their respective forces.

In September, Hamas created the Internal Security Force (ISF) (al-Amnu al-Dakhily), modeled on the Fatah-dominated Preventive Security, to combat politically motivated crimes, and staffed it largely with members of the Qassam Brigades. In October, it integrated the Executive Force into the civil police, which deals mostly with common crime. Hamas also assumed full control in Gaza of the National Security Force, a PA-wide force, responsible for security along Gaza’s borders, which Hamas refers to as its army.107 Some officials who defied Abbas’s order not to work were reappointed, including in some cases to command positions. Most prominently, former Fatah security chief Tawfiq Jabber was named commander of the 12,000-member civil police. He reported to Prime Minister Ismail Haniya, who also held the interior portfolio until April 28, 2008, when the influential Hamas official Said Siyam assumed that post.108 Even during Haniya’s tenure as interior minister, Siyam was widely considered the man in charge of the security forces.

Siyam has claimed that the new security forces are depoliticized, and that the al-Qassam Brigades plays no role in Gaza’s internal security. “The Qassam are the military arm of Hamas for resistance against the occupation,” he said. “They have no internal role. Any member interfering in internal security will be treated as a violator of the law.”109 Journalists and human rights activists in Gaza, however, dispute that claim, saying that Hamas has appointed security force members and commanders whose primary loyalty is to the movement.110

The Haniya government gave some signs of wanting to respect rights. On September 19, 2007, it issued Order 128/2007, which directed the security forces to respect human rights. In particular, the order instructed all members of the security forces to:

- Respect “political and media freedoms;”

- Respect “political diversity” and the right to hold demonstrations according to the law;

- Respect the ban on torture and violence against detainees;

- Prohibit political detentions

- Prohibit arrests without a judicial order

- Detain individuals only in official detention facilities

- Inform all arrested and detained people of the reasons for their arrest or detention, and grant them access to a lawyer

- Allow human rights organizations to visit detainees according to the law.

The order emphasized that any person who disobeyed these instructions “will be accountable before the law.”111

Over the second half of 2007, Hamas established a degree of order and control. Common crimes and armed clashes decreased as security forces cracked down on criminal groups and Gaza’s well-armed clans, including the powerful Dughmush family.112 The Executive Force banned the public display of weapons, unofficial roadblocks and celebratory gunfire at weddings.113

But there was no imposition of order with regard to the rule of law and human rights. First, until it was absorbed into the police in October, the Executive Force, as an armed group, had no legal authority to make arrests or hold people in detention, although it was doing so. Second, after October the Executive Force-infused police regularly violated the law: warrantless arrests, beatings and torture of detainees, and abuses of due process were common.

Over the past year, Hamas authorities have maintained pressure on the media, closing several radio stations and banning pro-Fatah newspapers. On August 25, 2007, Executive Force members attacked journalists covering a Fatah demonstration.114 On September 7, 2007, the Executive Force beat Fatah supporters as they tried to hold a public prayer meeting, again assaulting at least seven journalists and detaining five others covering the event.115 On December 14, 2007, members of the ISF arrested Omar al-Ghul from al-Hayat al-Jadida, a newspaper considered pro-Fatah. On January 15, 2008, they detained the paper’s Gaza bureau chief, Munir Abu Rizq, for about 20 days.116 That same month, authorities blocked the Gaza distribution of three newspapers published in the West Bank: Al-Quds, Al-Ayyam, and Al-Hayat.117 A ban on the pro-Fatah Palestinian TV remained in effect.118

Hamas also imposed restrictions on freedom of assembly, including public prayers by Fatah supporters. On August 13, 2007, the Executive Force issued an order that banned any demonstration without permission from the Executive Force.119 In the second half of 2007, the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights documented “several cases in which the Executive Force dispersed peaceful assemblies by force.”120

In its letter to Human Rights Watch, the Hamas government said that it fully respected the right to free assembly, as guaranteed in the Palestinian Basic Law and the Law on Public Assemblies, the latter of which states that the organizer of any meeting or demonstration must request permission from the authorities 48 hours in advance.121

But even when permission for demonstrations was granted, the police and other Hamas forces sometimes used excessive force to disperse crowds. In the most deadly incident, documented below, on November 12, 2007, security forces fired into a large pro-Fatah demonstration, killing seven and wounding 90 (see case below). Thirty-eight policemen were eventually held responsible for those deaths, but it remains unclear whether the punishments they received—ranging from dismissal to imprisonment—were commensurate with the crimes.

Hamas did not deny that abuses took place in the first months of its rule. Interior Ministry spokesman Ihab al-Ghusain told Human Rights Watch:

There were many mistakes by the Executive Force after June because they were not meant to be more than an auxiliary force. There were some attacks on journalists and illegal detentions… We are very annoyed and discontent with these problems. The higher levels of the administration including the prime minister were very upset. We’ve dealt with many cases and now we can notice that the mistakes have decreased or stopped. If they continue, then the responsible party will be brought to account.122

Al-Ghusain did deny, however, that any of the arrests had a political taint. “They accuse us but I can confirm again that there are no political detainees,” he said.123

The disintegration of the criminal justice system since the Hamas takeover has contributed to the breakdown in respect for the rule of law and continued impunity. After the Hamas takeover, the attorney general stopped investigating and prosecuting criminal cases in Gaza. On July 2, the chief justice of the Supreme Court and head of the Higher Judicial Council, both based in the West Bank, instructed the heads of the courts of first instance and arbitration in Gaza to “suspend all decisions requiring police assistance for their implementations, in order to protect the independence and dignity of the judiciary.”124

Hamas moved quickly to fill the void. On August 14, the Hamas Minister of Justice Yousef al-Mansi suspended the Attorney General Ahmad al-Maghani, claiming that his appointment papers were incomplete. Two days later, Hamas security forces raided the attorney general’s office and briefly detained him and his assistants. On August 29, the minister of justice appointed a new deputy attorney general, Ismail Jabber, who served as acting attorney general.

On September 4, in violation of Palestinian law, the Hamas authorities formed a new Higher Justice Council to replace the Ramallah-based Higher Judicial Council, with a mandate to run Gaza’s justice system.125 They approved the council’s members one week later, with Abdel Raouf al-Halabi appointed the body’s head. “The Higher Judicial Council did not serve all Palestinians,” al-Halabi told Human Rights Watch to explain the formation of the new council. “Instead, it became biased towards one party against the other.”126

Al-Halabi implicitly accepted that the procedure for appointing the council was not legal, but he suggested that the authorities had no choice. “Normally the council is appointed by the president of the Palestinian Authority, but because of the circumstances and out of necessity and because it is illegal that the structures are not working—hospitals must work, the education system and the courts—Haniya used his authority and formed the Higher Justice Council.”

Judicial paralysis followed, as judges and prosecutors refused to follow the orders of a Higher Justice Council they did not recognize. On November 26, 2007, al-Halabi and some colleagues, accompanied by police, physically occupied the civilian court compound in Gaza City, informing judges and court staff to follow al-Halabi’s instructions. In protest, Gaza’s judges went on strike. Al-Halabi gave them one week to return, and he suspended them from work when they refused. Forty-eight judges left their jobs, as did 541 court employees, al-Halabi said.

The Higher Justice Council quickly appointed replacements, including al-Halabi as chief justice of the Supreme Court. As of mid-April 2008, it had appointed 24 new judges across Gaza, as well as 115 court employees.127 They had all passed the requisite exams and were appointed “according to the law,” al-Halabi said.

Lawyers in Gaza dispute that claim, stressing that, the legality of the new High Justice Council aside, judges must also be appointed by presidential decree. Without this check, some of the new judges, they say, are pro-Hamas, and most of them have never worked before as judges. Al-Halabi accepted this latter fact, saying that only one of the new judges has experience as a judge, but he otherwise defended the new appointments. “We were committed to fill the gaps,” he said. “If we suppose the formation [of the High Justice Council] was illegal, what is the solution? Should we leave criminals free to attack citizens?” Gaza-based human rights groups see it differently, saying Hamas has intruded on the judiciary and politicized the courts. “Human rights organizations call upon the dismissed government to immediately rescind the illegal decision to take over the civilian judicial system in the Gaza Strip,” four of Gaza’s leading human rights groups said in a joint December statement. “These organizations hold this government fully responsible for undermining and destroying the Judicial Authority in order to establish illegal judicial bodies that are not independent.”128

At the same time, some lawyers and human rights activists in Gaza say that a semblance of normalcy has returned to the justice system in recent months, especially compared to the chaotic period after June 2007. Arrest warrants are issued more regularly and detainees are increasingly brought before prosecutors and judges within the required time. Reports of torture are down.

According to al-Halabi, as of April 13, the newly staffed courts had completed 205 civil cases and 383 criminal cases. This is out of 3,590 civil cases and 3,077 criminal cases in the system, he said.

But human rights abuses have hardly disappeared, and human rights groups still report disturbing cases of abuse, including a death in detention in late June.129 A human rights lawyer from ICHR explained:

From June to September 2007, the performance of the police was very bad with regard to respect for the legal procedures. There were arrests without a judge’s order and lengthy detention periods. But citizens were glad when a thief was arrested. After September we saw a clear improvement in the behavior of the police. Slowly they put regulations in place. They have created a general prosecutor and judicial structures. With the internal security organization, however, which is in charge of political security, we still document failures to respect the regulations. We see arbitrary detentions, torture, political detainees and restrictions on freedom of movement and expression.130

According to Fatah, its members are under siege, and they must stop their political activity or risk arrest.131 In June 2008, reflecting on one year of Hamas control, a Fatah supporter named Muhammed Huasanain told the BBC:

The last year, since Hamas took over, has been a very difficult time for me and my family. Hamas accused my brother of injuring some of their men in a shootout. They surrounded the house, but he escaped and managed to get out to the West Bank. Me, my parents, his wife, and his children haven’t seen him since.

He can come back, but there are no guarantees that he will be safe here.

Fatah people have got no voice and no power here in Gaza under Hamas control. They stop us having rallies—and use electric batons to hit us if we do.

Even on personal issues, if you go to any ministry which is controlled by Hamas, they want to make things difficult for Fatah supporters.132

Human Rights Watch asked the Palestinian authorities in the West Bank for information on Fatah members who had been arrested or gone missing in Gaza since June 2007, but as of July 10 the authorities had not replied. According to one media report, as of late June 2008, 46 Fatah members were detained in Gaza, but this number is unconfirmed.133

As in the West Bank, lawyers in Gaza have complained of restrictions on visiting clients in detention. In April, PCHR publicly expressed concern that the restrictions were “motivated by the perpetration of illegal actions such as torture and other forms of cruel and inhumane treatment against prisoners.”134 PCHR said its lawyers had not been able to visit any of their clients for more than two months (February 20 to April 20), and that the organization had documented at least 30 cases in which lawyers were forbidden from visiting their clients despite prior coordination with the authorities.

In its response to Human Rights Watch questions, Hamas authorities denied any restrictions on access for lawyers. “The government provides all possible facilities for lawyers to communicate with their clients and to preserve their legal and constitutional rights,” the letter said.135

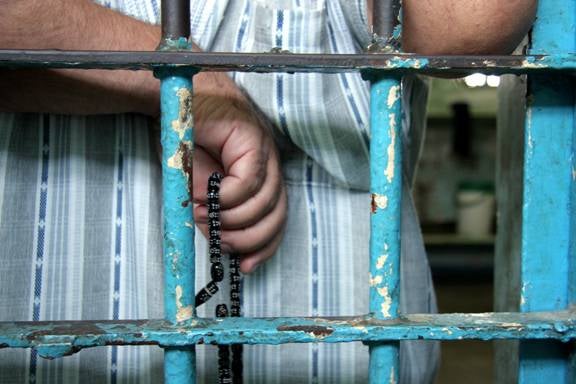

The interior ministry in Gaza allowed Human Rights Watch to visit Gaza Central Prison on October 12, 2007. According to the prison spokesman, the prison held 230 prisoners at the time.136 Most of those inmates were serving time for theft, drugs, or violent crimes, he said. A few were so-called “security criminals,” who had been convicted of crimes related to their supposed collaboration with Israeli security forces.

An inmate in Gaza Central Prison, October 2007. © 2007 Fred Abrahams/Human Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch inspected the prison facilities without restriction and was allowed to interview 11 prisoners, six men and five women, in one-on-one settings. The prisoners all said that conditions at the prison were adequate. None of them complained of abuse. Their main complaint was a lack of due process. Three of them—all arrested for alleged collaboration with Israel—had started their trials prior to June 2007, but those trials had failed to resume. The other prisoners arrested after June had faced no criminal proceedings at all. None of the prisoners with whom Human Rights Watch spoke had information about the status of their case.

On October 12, the interior ministry also granted Human Rights Watch permission to visit al-Mashtal, a facility run by the Internal Security Force, but guards at the facility refused entry. The ministry apologized for the confusion, and offered to coordinate another visit, but a lack of time prevented this from taking place. Human Rights Watch did, however, speak with the legal affairs director of the Internal Security Force, Abdalla Abu Luli, who said that al-Mashtal was holding 43 prisoners at that time, October 12, out of a 300-person capacity. He denied any political bias in the ISF’s work. “We have no political detention here,” he said. “Our work is limited to crimes involving the general security of the Gaza Strip, regardless of who committed the crime.”137

Hamas appointed guards praying in Gaza Central Prison. The freshly painted slogan says: “No Injustice Today – the Executive Force” © 2007 Fred Abrahams/Human Rights Watch

According to Abu Luli, the ISF started work on September 1, 2007, and in that first week interrogators received an internal note not to use physical force during interrogations. In the second week of September, an interrogator was fired for violating the instruction, he said, without providing details.

The ICHR is the only human rights group with regular access to al-Mashtal, police stations, and other places of detention, although human rights groups such as al-Mezan, PCHR and Addameer have had access on an ad hoc basis. Hamas authorities have generally allowed these groups to work unhindered, although ICHR came under attack in the pro-Hamas media after its March 2008 monthly report, which was critical of the interior ministry and justice system.138

A constant problem for human rights groups in Gaza is victims’ unwillingness to report abuse. “Some people were told by the Executive Force that if they spoke to human rights groups or the media, or even if they went to the hospital, then they would be taken again,” one Gaza human rights activist said in October. “About 90 percent of our cases were warned not to speak.”139 Another Gaza activist agreed. “Some people are too afraid to speak,” he said. “Even those who gave us their testimony have then called to say, ‘Don’t use it.’”140

As in the West Bank, impunity is disturbingly common. Human rights lawyers and activists told Human Rights Watch that very few security force members or commanders have been held accountable for their illegal acts, and punishments meted out frequently failed to match the severity of the crime.

Interior Ministry spokesman al-Ghusain acknowledged that mistakes had been made but said that the authorities punished persons responsible for abuse. Disciplinary action against abusive forces included temporary detention, demotion, salary reduction and dismissal, he said. According to al-Ghusain, three senior police officials had been dismissed for using excessive force between June and October 2007, including one in Rafah who chased a group of Fatah members who had thrown a grenade into a hospital, where he beat up some civilians. Al-Ghusain provided no dates or names.

In response to a Human Rights Watch request for information on accountability for police and ISF forces, Ismail Haniya’s office said the Hamas government strived to discipline forces who violate the law. Regarding the police, the government had punished 35 officers for “violating human rights”141 and 774 officers for violating the principles outlined in Order 128/2007 (see above).142 The difference between these two characterizations remains unclear. Human Rights Watch was unable to confirm the Hamas authorities’ claim.

Regarding the ISF, the government claimed to have disciplined nine members of the force by suspension from work, a salary freeze or an official rebuke.

Below is a selection of human rights abuses by Gaza security forces documented by Human Rights Watch, in reverse chronological order.

Death of Sami ‘Atiya Khattab

In the evening of April 13, 2008, two armed men came to the shop of Sami ‘Atiya Khattab, a 36 year-old father of five, and took him away. About 36 hours later police called the family to say Khattab had been found dead. Khattab was a former captain in the General Intelligence Service. The circumstances of his death remain unclear.

Human Rights Watch interviewed two people who witnessed Khattab’s arrest. One of them saw two vehicles and the other saw three, but both said they saw two armed men in dark clothes take Khattab out of his shop and put him into one of the cars just before 8 p.m.143

One of Khattab’s relatives explained what the family did next:

When Sami was kidnapped, we made unofficial contact with people close to Hamas on their personal capacities. They informed us that Sami was held by the internal security service [ISF]. Those people are mostly involved in political and public activities of Hamas, away from the military thing.

The next morning, we called the police and told them about Sami, since they are the de facto power. Nai'm al-Kurd, chief of Deir al-Balah police station, told me on the phone that we must go to the station and officially tell them about the kidnapping of Sami.

At 9 a.m., the mukhtar (clan head) of our family, Ismail Mohammed Khattab, and his son Fuad went to the station and wrote a memo about the kidnapping.

At 5 pm, the director of the station called me on my mobile -I have a previous tie with him when we were prisoners in an Israeli jail in the past. He told me that Sami is not held by the police and that he is held by the internal security and he doesn’t know where he is held exactly, whether in Dir al-Balah or in Gaza City. He also told me that Sami's story was easy and that it was only his long tongue which talks so much. He also said it was difficult for the police to intervene when it comes to the internal security and that they don't accept such intervention. I told him: anyway, keep us posted if you get any new information.

The next day, Tuesday, at 9:45 a.m., Nai'm al-Kurd phoned me and said he has got bad news: a dead body was found in Netzarim settlement, and probably it was Sami. I told the family about this and started to go to the hospital to get the body.144

After the police called, one of the relatives who saw Sami get arrested went with another relative to see Sami’s body. They drove past the Netzarim settlement on the way and went to take a look. “We went to the body which was on the ground, it was Sami’s,” the relative said. “His hands and feet were tied up with a white rope and his body was wrapped with a rug, the same rug that is used in the police stations and the jails. Most of his body showed clear signs of torture.”145

Human Rights Watch spoke with another relative who saw the body at al-Shifa hospital and explained what he saw:

We took Sami’s body out of the ambulance. He was tied up and wrapped in an old rug. Under the rope, the skin was torn because the rope was very tight. His legs were also bound. It is the same rug that used to be distributed in the Palestinian Authority security facilities.

Officials for the autopsy and Hamas police came. In front of the morgue, the policemen prevented the journalists from filming and tried to search us to take the mobile phone cameras. We were about 40, and the policemen's number was a little but higher than ours.

We scuffled with the policemen after they tried to search us for mobiles. They pointed their guns at us and about 15 of them fired sporadic shots in the air. They pushed some of us with their guns.146

PCHR staff members were able to inspect Khattab’s body and reported seeing cuts and bruises all over the body, which strongly indicated that he was subjected to severe physical violence during his abduction.147 This matched what a lawyer and field worker from the human rights organization al-Mezan observed:

At first glance, obvious signs of torture, including black-and-blue marks, were found all over his body. Bruises and abrasions were found on his upper and middle back, elbows, forehead, and the area from the top of his buttocks to the backs of his thighs. There were clear signs that his wrists and ankles had been tightly bound.148

Following a public outcry about Khattab’s apparent unlawful killing by security forces, non-Fatah and non-Hamas members of the Palestinian Legislative Council from Gaza and the West Bank formed a special committee to investigate the case, similar to the PLC committee that investigated the death in custody in Ramallah of Majid al-Barghuti (see chapter, West Bank: Abuses Against Hamas). The members of the two committees are the same: Qaiss Abu Laila, Bassam al-Salehi, Mustafa al-Barghouti, Khalida Jarrar and Hassan Khraisha, plus Hussam al-Tawil from Gaza.

On May 19, Hussam al-Tawil told Human Rights Watch: “So far, there is no thing new on this issue because we are waiting for the arrival of the committee’s members from the West Bank, and this delay is due to the Israelis. There are efforts by the Palestinian presidency to issue the permits for the committee members.”149

The family, meanwhile, had no news from the Hamas government as of late April. “What makes us crazy is that we don’t know why he was kidnapped,” Sami’s wife Suad said. “We don’t know what happened and why, but suddenly, after 24 hours, we were shocked by his death.”150

November 12, 2007, Demonstration in Gaza City

One of the most violent incidents since the June 2007 takeover occurred on November 12, 2007, when about 250,000 Fatah supporters gathered in Gaza City, with official permission, to commemorate the third anniversary of Fatah founder Yasir Arafat’s death. The gathering was the largest show of support for Fatah since Hamas seized control of the territory. According to testimony gathered by Human Rights Watch, Hamas security forces, which at times came under attack from stone-throwing demonstrators, opened fire in an indiscriminate manner on the crowd, killing seven and wounding more than 90. After an investigation, the Hamas authorities said they punished 38 unnamed policemen with imprisonment, dismissal or demotion for failing to prevent the killing.

Human Rights Watch interviewed three shooting victims from the demonstration and five eyewitnesses, as well as hospital, health ministry and interior ministry officials in Gaza. According to their testimonies, the demonstration was scheduled to start at 1 p.m. at the al-Qatiba grounds near al-Azhar University. By late morning, large crowds had assembled around the university. Three witnesses told Human Rights Watch the atmosphere was peaceful but tense, and that Hamas security forces had established checkpoints and posted gunmen on the roofs of tall buildings. Hamas members in civilian clothes mingled with the crowd, they said. Demonstrators taunted the security forces with chants of “Shi`a! Shi`a!” – a common provocation in Gaza that refers to Hamas’s support from Iran, a predominately Shi`a country. Most Palestinians, including Hamas members and supporters, are Sunni.

According to the Palestinian Center for Human Rights, the first clash began around 11:30 a.m. Hamas security forces opened fire and killed Tariq Mahmud al-Najjar, age 29, with bullets to the chest and right hand, although it remains unclear why the forces shot.151 The interior ministry spokesman told Human Rights Watch he was killed by Fatah gunmen on nearby rooftops on al-Sina’ Street, about 300 meters from the rally site.152

The violence worsened around 1 p.m., after large crowds listened to speeches from Fatah leaders. A group of stone-throwing Fatah supporters confronted Hamas security forces, who reportedly fired automatic weapons into the air and then, according to witnesses, indiscriminately at the crowd. According to one man who was wounded, the violence started when security forces tried to arrest three Fatah supporters who were taking photographs with their mobile phones, although he did not witness this himself.153

According to figures from Al-Shifa Hospital and the Hamas-run ministry of health, in addition to Tariq Mahmud al-Najjar, the following people lost their lives:

- Ibrahim Mahmud Ahmad, 13, from Beit Hanoun

- Hosam Badr al-Oadi, 26, from Gaza City

- Kamil Ziyara, 19, from Beach refugee camp

- Muhammad Ahmad al-Masri, 67, from Khan Younis

- Ayub Abu Samra, age unknown, from Deir al-Balah.

- A seventh person, Marwan al-Nunu, 21, died two days later from bullet wounds.

An official at Al-Shifa Hospital told Human Rights Watch that all of the victims died from gunfire, most of them shot in the head. According to PCHR, the bullet wounds of the five people mentioned above were in the neck, head, chest, chest, and head, respectively. The seventh casualty, al-Nunu, who died two days later, was also shot in the head.

After the shootings, witnesses saw Hamas members in civilian clothes beating people with sticks and batons. According to hospital records viewed by Human Rights Watch, 94 people received medical treatment for injuries sustained during or after the demonstration. Of these people, 50 were treated at Al-Shifa Hospital and the rest at Al-Quds hospital in southern Gaza City.

Human Rights Watch interviewed three of the wounded demonstrators at Al-Shifa Hospital. Y.G., a 16-year-old boy, said he heard gunfire as he was going home at the end of the demonstration:

At the intersection [by Al-Azhar University] I saw a man who fell on the ground after being injured. I ran to help him but as soon as I arrived a bullet hit my arm. I don’t know where the bullet came from. There was a seven-story building overlooking the crossroads, and Hamas gunmen were firing from the roof and the other policemen were also firing, some in the air and some at the demonstrators. With my own eyes, I saw three policemen at the crossroads taking up positions like snipers and they fired at the people.

The people started to shout “Shi`a! Shi`a!” at them and they threw stones at Hamas policemen. There were no armed men among Fatah, only bodyguards of Abu Mahir Hillis, a senior Fatah leader in Gaza, were armed with pistols and one of them was armed with a Kalashnikov but they left before the violence started.

I was running like a crazy boy because of the pain in my arm. There were no cars. People carried me from time to time to get me out of the square. I learned later that the problems started when the policemen tried to arrest three Fatah supporters who were using their mobile phone cameras and filming near the crossroad where many policemen and gunmen, dressed in civilian clothes, were deployed. The people tried to prevent Hamas from arresting the three guys and the shooting started from here.154

A 22-year-old Fatah supporter from Deir al-Balah explained how he was wounded:

I came from Deir al-Balah to the rally. When it ended around 12:30, I suddenly heard some gunshots that came from behind. I went there, to [the Al-Azhar University] intersection – about 50 meters from the main police compound in Gaza – and found dozens of Executive Force [Hamas] members, who were on full alert and pointing their guns at the people.

The people shouted ”Shi`a! Shi`a!” at Hamas. I came closer but suddenly one of the Executive Force men opened fire randomly at the people. A young guy next to me was killed immediately and I was wounded by a gunshot in my right leg. I arrived at the hospital after almost two hours because the ambulances were unable to come to the place and there were no cars because of the number of people.155

A.H., age 17, explained how he was shot in his abdomen:

I ran for cover, as most of the people did when the shooting suddenly started at the end of the demonstration. While I was running, a gunshot hit me in my abdomen. I don’t know where the bullets came from but I can confirm that I did not see any weapons with anyone from Fatah. When the Executive Force attacked the rally, the people threw stones at them.156

According to PCHR, Hamas police temporarily detained at least three journalists covering the demonstration, including at least one foreign reporter, Paul Martin, who wrote about the incident in The Times of London.157

According to Ihab al-Ghusain, the Ministry of Interior spokesman, Fatah was to blame for the violence. He said four policemen were fired upon and lightly wounded in northern Gaza before the demonstration and two others were wounded in a drive-by shooting in the area of Nusseirat, south of Gaza City. During the demonstration, he said, Fatah gunmen were positioned on rooftops overlooking the demonstration and on the buildings of Al-Azhar University.

“There was a Fatah plan in advance to cause trouble and riots after taking advantage of the large crowd,” said al-Ghusain. “And, yes, of course, after the speakers finished their speeches, gunmen on Al-Azhar University [rooftops] fired at the people and the police. The policemen got close to the scene to see who was firing but the gunmen continued to fire and these unfortunate incidents have continued and ended with the death and injuries of a number of Palestinian people.”158

The police arrested two of the Fatah gunmen, he said, in addition to a number of “trouble-makers” who were arrested at the demonstration. The police also confiscated pipe bombs and pistols, he said.

On November 13, the day after the demonstration, Human Rights Watch visited the intensive care unit at Al-Shifa Hospital, where the following people were receiving care:

- Mahmud Muhammad al-Rifa`i, 23, gunshot to the neck

- Yusif al-Dairi, 18, gunshot to the head

- Marwan al-Nunu, 21, gunshot to the head (later died)

- Ahmad al-Wadi`a, 20, gunshot in the abdomen

The ministry of health also provided some details of others who were wounded:

- Four people, including a 5-year-old boy, `Atif al-Ghar, were wounded in the head.

- Six wounded people received treatment for broken bones.

- Eight people received treatment for shock.

- Five people received treatment for severe beatings: Muhammad Madi, 20, from Khan Younis; Naji Sulaiman, 24, from the Beach refugee camp; `Ola `Adnan Sha`th, 20, from Khan Younis; Yihya Ahmad al-Najjar, 23, from Jabaliyya; and Basim Abu `Obaid, 22, from Rafah.

In the days after the demonstration, Hamas security forces arrested scores of Fatah members and supporters—450 people according to Fatah, but that number remains unconfirmed. The Interior Ministry spokesman told Human Rights Watch that those detained “are not more than 100.” They were being held at the al-Mashtal facility, he said. Human Rights Watch does not know if they were subsequently charged or released.

On November 15, Ismail Haniya announced the creation of an “honest, fair and transparent” commission to investigate the violence of November 12.159 He also ordered the release of Fatah members and supporters arrested after the demonstration, except for those “involved in riots and disturbances.”

On June 2, 2008, Hamas announced that it had punished 38 policemen for failing to prevent the killing of the seven people who died. Hamas spokesman Taher al-Nono said the police had “failed to implement and had violated orders.”160 The unnamed policemen were given punishments ranging from jail sentences to dismissal and demotion, he said, without providing details on the specific punishments or the violations for which they were punished.

International legal standards on use of force, including the United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials, provide that officers shall, as far as possible, use nonviolent means before resorting to the use of force and firearms. Whenever the lawful use of force and firearms is unavoidable, forces must exercise restraint in such use and act in proportion to the seriousness of the offense and the legitimate objective to be achieved, and also minimize damage and injury. The prohibition in international human rights law on the arbitrary taking of life also requires authorities to set up independent investigations where state authorities (such as the police) may have caused arbitrary loss of life. Such investigations should involve the families of the victims and lead to the identification (and prosecution) of anyone responsible for the arbitrary taking of life.161

Man in al-Shifa Hospital

On October 14, 2007 Human Rights Watch visited al-Shifa hospital and saw an unconscious young man in the intensive care unit with a broken left arm and cuts and bruises on both legs. His family at the hospital said that he had been beaten by the police four days before. His father told Human Rights Watch:

On October 10 a large group came to our home, more than 50 men, armed, around 2:30 in the morning. They called for him. We woke him up and they took him away. They said they were from al-Qassam Brigades and my son had planted a bomb to get one of their members. The police dropped him here at Gaza hospital some hours later.162

Human Rights Watch viewed a medical report from the patient, dated October 10, which said the police had brought the young man to the hospital the previous day with “impaired conscious level and resp.[iratory] distress.” Doctors found no skull fracture or brain damage, but a fracture of the left forearm (lower one-third of the ulna), the report said.163 There was no explanation as to why he was in a coma.

This young man, name withheld, lies unconscious in the intensive care unit at Gaza’s al-Shifa Hospital on October 14, 2007. His family said `Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigade members had arrested him four days before. © 2007 Fred Abrahams/Human Rights Watch

E.M. in Gaza City

In early October, a former Fatah official, E.M., was sitting near his home in northern Gaza City when he said he was approached and forcibly taken at gunpoint by two masked men. Interviewed in al-Shifa Hospital a few days later, he told Human Rights Watch:

The bus drove about 20 minutes after they blindfolded my eyes. They beat me frequently during the trip with the butts of their rifles and rubber hoses. They also punched me several times on my head to lose concentration. I don’t know where they took me.

There they started to interrogate me: “You were late. You have tired us out until we caught you. Welcome, big man. Are you a spy and collaborator? Are you an adulterer? What are your relations with Dayton [Fayyad] government?

The answers to their questions had to be no, so whenever I answered they beat me and said that I didn’t want to cooperate with them. They told me that they came from Beit Hanoun and that I was in being interrogated in that same city.164

Around 11:00 p.m., E.M. said, his captors said they were going to “get rid” of him because he refused to cooperate. They drove off again in the small bus for approximately ten minutes and then blindfolded him:

They took me out and wanted me to raise my hands to a wall, but they heard the sound of cars coming so they hurried up and shot me in my right leg. I fell down and one of them said let’s shoot him in the other leg, but another one said it was enough “because he fell down” and they drove away.

Residents of the area came after a few minutes and E.M. saw he was in an agricultural area near Mohammed al-Durra Hospital in northeast Gaza City. An ambulance came and took him to al-Shifa Hospital, where he spent at least two days in the intensive care unit. When Human Rights Watch visited him on October 8, large bruises were visible on his upper body.

Yusif Mohamed Abu Hussein in Gaza City

On October 1, 2007, masked and armed men abducted Yusif Mohamed Abu Hussein, a 28-year-old father of three, who had worked for ten years with the PA National Security Force. They held him for a few hours, during which time they beat him severely, cut his feet between his toes, and shot him three times with a pistol in his left leg. Human Rights Watch interviewed him 10 days later and observed the wounds.

According to Abu Hussein, on the evening of October 1, 2007, around 8 p.m., he was sitting with some friends near his house in Gaza City. A Jeep Wrangler pulled up and six masked men got out with guns. Some of them fired into the air and others at the ground, he said. Two gunshots wounded his uncle who was standing nearby. The men grabbed Abu Hussein and, with pistols to his head, ordered him into the jeep. He was handcuffed with his hands behind his back and a blindfold over his eyes.

According to Abu Hussein, the men drove the jeep a few hundred meters away and pushed him out. They forced him to the roof of a house, where they beat him severely with a stick. He said:

They cut with a knife between my toes. They also used rubber hoses on my arms and back. “Where do you work?” they asked. I said in security and I gave them my military ID. I said I’m a member of the National Security Force. Two guys were holding me arms while the others kept beating me. I was blindfolded and a nylon bag was on my head. Someone was stomping on my feet.165

After about one hour they took him back to the jeep, and then to a place nearby he said was used as a parking lot. “It was empty. They took me out and opened fire on my legs. They shot me while I was lying on the ground. They said “Now we’ll drive over your legs.” They tried but somehow I was able to roll away.”

Abu Hussein was hit with three bullets in his left leg by a pistol. Human Rights Watch saw the wounds in the leg, and also the cuts between the toes.

In October 2007, Hamas security forces in Gaza City detained Yusif Mohamed Abu Hussein, who had worked for ten years with the National Security Force. They fired three bullets into his left leg and cut the skin next to his right big toe, he said.

© 2007 Fred Abrahams/Human Rights Watch

According to Abu Hussein, he and his family decided not to file a complaint with the police. “To whom should I complain,” he said. “Because it’s the same people.”

B.R. in Khan Younis

B.R., age 36, was a police officer in Khan Younis before the Hamas takeover. He said the Executive Force detained him in late September, together with six neighbors, beat him and detained him for four days in a police station without charge.

The problem began, he said, when Hamas replaced the imam of the local mosque in his neighborhood with one of their own. The residents protested and the police arrested B.R.’s 15-year-old nephew for reasons that remain unclear. About 20 minutes later, the family learned that the police had dropped the nephew off in front of Nasser Hospital, suffering from the effects of what appeared to be a beating. “Doctors were hesitant to treat him when they knew he was beaten by Hamas,” B.R. told Human Rights Watch. “I took him to a private doctor, he gave him some hypodermic injection and I took my nephew back to the house.” B.R. explained what happened next:

At about 7 p.m., four masked gunmen of the [Hamas] fighters that were deployed in the area approached me. Some of them were dressed in black and others were wearing the Executive Force uniform. They said, “Come with us.” I tried to escape but they fired around me and took me to their cars that were waiting at the end of the street, about 100 meters away. They forced me to make my way in front of them with their sticks, and they kept hitting me until we reached one of their pick-up trucks.

They threw me inside after blindfolding me and handcuffing me. One of them told the driver to go to al-Qassam site, which I know is located in the former settlement Gush Qatif. All the way, they were poking me with their legs and saying, “You are infidels, dogs, and spies.”

When we arrived, they put a sack on my head because they believed that I might have been able to see. I think we were in a room with about six other detainees. They asked me my name and work and I told them. These were the only two questions they asked. They asked the others and I found out that all of them were my neighbors.

Following this, they have started to beat us one by one with sticks. They beat me for about five minutes before continuing to the next detainee and they repeated the process every half an hour. They focused their sticks on the shoulders, the foot and the back. They were not asking us questions.

After that, they pushed us and let us walk on a floor but suddenly I fell. We were walking on a higher surface; I fell from about two meters high. When I fell, another group hit me with the sticks for about ten minutes.

They threw us back into the jeep and drove to a Khan Younis police station. Along the way, they continued beating us and they ignored the orders that came from the jeep that followed us. It was night. At the police station, they removed the cover from our eyes and freed our hands. An interrogator took our statements about the troubles that took place in our neighborhood. The interrogator wrote a note to hold us for 24 hours at the station. They put us in the detention cell at the police station. I asked them to let me go to the hospital for a check-up but they said no. We remained there for four days at the police station and they released us on October 4.

In order to legalize the detention, they said that someone had filed a complaint against me with the police. They mentioned his name but it was the first time that I heard that name. They forced me to sign a pledge not to harm that guy.166

Alla Yassin Abu Awad in Gaza City

Alla Yassin Abu Awad, a 33 year-old father of four, worked prior to June 2007 as a captain in the General Intelligence Service. He served in the al-Mashtal facility, and in August 2007 he spent a long night there in detention himself.

According to Abu Awad, in the evening of August 12, 2007, unknown men came to his home with a warrant for his arrest. He was not home at the time but they left a document with “Executive Force” written on top that said he had to report to the police station at the Beach Camp in northern Gaza City immediately. He went that night around 10:30 together with his uncle.

At the police station, officers confiscated his possessions, blindfolded him, and put him in a jeep with two other men who had been arrested that night. Together they drove to al-Mashtal. Abu Awad explained what happened next:

First, as the jeep stopped, they started to shout and hit the jeep to make us confused. Before we got out, as my leg hit the ground, they started to beat us and curse us. They took us underground into what I think was a small room. The continued beating me and they moved me to another room. I felt I was alone. I don’t know what devices they used but they beat me on my back, backside, the back of my legs and shoulders.

Human Rights Watch saw photographs of Abu Awad that showed deep bruising on his backside, back, legs and shoulders. He said they had been taken just after his release on August 13. Abu Awad continued:

In the first room, the Executive Force guy asked his colleague to bring a pistol. He did and he put it to my head and said: “If you don’t speak I’ll kill you.” They didn’t ask questions, only where I worked. But they knew I was with intelligence. I felt like it was just for revenge and torture.

In the second room, my hands were tied behind my back to a chain on the wall. They asked me to step on a chair. I couldn’t see a chair, so they raised me and put me on a chair. Then they raised me up on the wall. I started to scream because it was very painful. They were pushing me back and forth for 10 to 15 minutes. Then they put me down on the ground on my back with my hands tied behind. They brought an office chair and hit me on the bottom of my feet with heavy sticks. This was for less than 15 minutes. Two of them were holding my feet. Then they told me to stand up and to jump. When I couldn’t anymore from the pain, they beat me on my toes.167

After this the interrogators took Abu Awad to another room, where they untied his hands but kept him blindfolded. He slept the night there and was awoken the next morning by cold water in his face. Then he moved to different rooms and was eventually made to sit in the corridor. The officials there, he said, made him sign a document promising to respect the law and not take part in any illegal acts. Around 6 a.m. they drove him back to the police station, where he was treated properly but scolded to respect the law. “The Fatah leadership has left you and fled to the West Bank,” he recalled they said. “We won’t show mercy on those who break the law.” Around 11:30 a.m. his captors released him.

During his time at al-Mashtal, Abu Awad said he heard different voices of prisoners. The next morning they saw each other and he recognized three of them as Fatah security members and four as Fatah political activists.

H.S. in Khan Younis

38-year-old H.S. from Khan Younis has eight children and comes from a known pro-Fatah family. His cousin is a commander in the Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades, he said, and other relatives are also members of the armed group, but he himself was not involved.

On June 18, 2007, around 7 p.m., neighbors came to H.S.’s home and said members of the Qassam Brigade wanted him outside. He went. According to H.S., they took him in a jeep with his head covered and his hands tied to the area called Maan, where they had a small compound at the beach near al-Tufa. They uncovered his head and started the interrogation, asking about the guns he owned. He explained:

They beat me with sticks and five sticks broke while they were beating me. From the torture I got 19 broken bones in my body, mostly on my hands and legs. They hit me with a metal bar. I fainted five times and then after the sixth time I stayed like that. They took me unconscious and dropped me in front of the hospital.168

When Human Rights Watch visited H.S. at his home on October 11, he showed photographs of himself taken in late June with casts on both arms and both legs. At the time of the visit, he still had a cast on his right leg up to his knee, and H.S. said he was waiting for surgery on his leg.

H.S., whose family was active in the al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade, said members of the `Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades in Khan Younis beat him in June 2007 with sticks and a metal bar. In September 2007, he still wore a cast. © Fred Abrahams/Human Rights Watch 2007

F.B. in Khan Younis

F.B., a 48-year-old father of five, worked previously as a guard at Preventive Security. On June 15, 2007, a group of men came to his home in Khan Younis and demanded he give them his weapons. He handed over three Kalashnikovs, he said.

About one week later, five armed men pulled up to his house in a jeep. He said he recognized them as members of the al-Qassam Brigades. They took him to a facility in town called Maan, previously used by Force 17, an elite special operations unit that reports to the Palestinian president. There they interrogated him, asking about his family members who were active in politics and militant groups. They accused him of helping a neighbor who was in Preventive Security. And, he explained, they used violence during the interrogation:

During the questions they were punching me in the head. They put a pistol to my head. Every two minutes they cocked their weapons and threatened me. Then they blindfolded me. They covered my head and then the interrogation started to get rougher. They were beating me and one kicked me hard in the back. The whole interrogation was them accusing me and me denying. They finally forced me to confess things I had never done.169

The beating and interrogation lasted about five hours, F.B. said, and then he was allowed to go home. He had not registered the case with the police for fear of retaliation.

104 “Black Pages in the Absence of Justice: Report on Bloody Fighting in the Gaza Strip from 7 to 14 June 2007,” Palestinian Centre for Human Rights.

105 On July 15, the dead body of Walid Abu Dhalfa was delivered to al-Shifa hospital, one week after his detention by Hamas forces. A spokesman for the Qassam Brigades said Abu Dhalfa died while trying to escape. (“Palestinian Man Dies after Taken Into Custody by Hamas,” Associated Press, July 16, 2007). According to PCHR, members of the Qassam Brigades tortured Abu Dhalfa and his brother, Khalil Salman, in the al-Mashtal detention facility. (“Palestinian Detained and Tortured in al- Mashtal Detention Center Dies,” Palestinian Centre for Human Rights press release, July 16, 2007, http://www.pchrgaza.org/files/PressR/English/2007/60.2007.html (accessed May 27, 2008).

106 “Annual Report 2007,” Palestinian Centre for Human Rights.

107 The commander of the National Security Force is reportedly a former PA security official, Hussein Abu ‘Athra. (See “Gaza Under Hamas,” International Crisis Group.)

108 “Haniya Expands Dismissed Government,” Deutsche Presse Agentur, April 28, 2008, http://www.monstersandcritics.com/news/middleeast/news/printer_1402236.php (accessed July 4, 2008). See also “De Facto Government Announce Cabinet Reshuffle,” Ma’an News Agency, June 4, 2008, http://www.maannews.net/en/index.php?opr=ShowDetails&ID=29699 (accessed June 23, 2008), and “Hamas Expands Cabinet to Strengthen Hold in Gaza,” Reuters, June 3, 2008.

109 “Gaza Under Hamas,” International Crisis Group.

110 Human Rights Watch observed this firsthand in October 2007 when visiting the Gaza border at Rafah. At least two of the approximately 12 National Security Force members were wearing black T-shirts of the Qassam Brigades, but they purposefully covered the shirts when posing for a photograph.

111 “Internal Order 128/2007, “For the Leadership of the Internal Security Forces,” Palestinian National Authority, September 19, 2007.

112 “Inside Gaza: The Challenge of Clans and Families,” International Crisis Group report, December 20, 2007, http://www.crisisgroup.org/home/index.cfm?id=5234 (accessed July 10, 2008). According to the International Crisis Group, on July 3, 2007, Hamas forces laid siege to the Dughmush quarter in Gaza City and arrested family members to pressure them into releasing the BBC journalist Alan Johnston, who was kidnapped on March 12. The Dughmush clan released Johnston the following day.

113 Ibid.

114 Letter from the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights to Prime Minister of the Dismissed Palestinian Government Ismail Haniya, September 13, 2007, http://www.pchrgaza.org/files/PressR/English/2007/letter13-9.html (accessed June 15, 2008).

115 Sarah el Deeb, “Palestinian Tensions Spark in Gaza,” Associated Press, September 7, 2007 and Letter from the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights to Prime Minister of the Dismissed Palestinian Government Ismail Haniya.

116 “Hamas Detains Bureau Chief in Gaza,” Committee to Protect Journalists media release, January 23, 2008, http://cpj.org/news/2008/mideast/gaza23jan08na.html (accessed May 27, 2008) and “Two al-Hayat al-Jadida Journalists Held by Hamas,” Reporters Without Borders media release, January 16, 2008, http://www.rsf.org/article.php3?id_article=25070 (accessed May 27, 2008).

117 “PCHR Concerned over the Detention of Distributors of Palestinian Newspapers by the Executive Force and the Delay in Distribution of Papers Today,” Palestinian Centre for Human Rights press release, July 30, 2007, http://www.pchrgaza.org/files/PressR/English/2007/75.2007.html (accessed May 27, 2008).

118 Letter from the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights to Prime Minister of the Dismissed Palestinian Government Ismail Haniya.

119 Ibid.

120 Ibid.

121 Letter to Human Rights Watch from the office of Prime Minister Ismail Haniya, June 4, 2008.

122 Human Rights Watch interview with Ihab R.A. al-Ghusain, interior ministry spokesman, Gaza City, October 11, 2007.

123 Ibid.

124 As presented in “Torn Apart by Factional Strife,” Amnesty International, footnote 20.

125 “Al Mezan calls the deposed Premier to revoke the decision forming a 'Supreme Council of Justice,” Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights press release, September 25, 2007, http://www.mezan.org/site_en/press_room/press_detail.php?id=716 (accessed May 28, 2008).

126 Human Rights Watch interview with Abdel Raouf al-Halabi, head of Higher Justice Council, Gaza City, April 13, 2008.

127 Six of the new judges were appointed to the court of first instance, 12 to the court of second instance, three to the appeals court, and three to the supreme court.

128 “Human Rights Organizations Condemn the Takeover of the Civilian Courts Compound,” Addameer for Human Rights, Palestinian Centre for Human Rights Palestinian Independent Commission for Citizens Rights, Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, December 6, 2007, http://www.pchrgaza.org/files/PressR/English/2007/06-12-2007.html (accessed May 17, 2008).

129 According to PCHR and al-Mezan, on June 26, 2008, police in Deir al-Balah arrested 72-year-old Taleb Mohammed Abu Sitta, together with his son Mustafa, on suspicion of drug dealing and took them to the local station. Abu Sitta’s dead body was transported to the hospital the following day. The son Mustafa told PCHR that the police had badly beaten him and his father, who was tied to a bed. (“PCHR Calls for Investigation into the Death of an Old Man in Suspicious Circumstances in the Police Station in Deir al-Balah,” PCHR press release, June 29, 2008, http://www.pchrgaza.org/files/PressR/English/2008/61-2008.html (accessed July 4, 2008) and “Elderly Man Dies in Deir Al Balah,” Al-Mezan press release, June 27, 2008, http://www.mezan.org/site_en/news_detail.php?id=2596 (accessed July 4, 2008).

130 Human Rights Watch interview with Basem Bushnaq, ICHR, Gaza City, April 12, 2008.

131 Human Rights Watch interview with Hazem Shanab, Fatah spokesman, Gaza City, October 13, 2007.

132 “Gaza Voices: A Year of Hamas,” BBC website, June 14, 2008, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/7453482.stm (accessed June 14, 2008).

133 “Hamas, Fatah to Release Hostages They Hold,” Xinhua, June 24, 2008.

134 “PCHR is Concerned Over the Ban of its Lawyers from Visiting Prisons in the Gaza Strip,” PCHR press release, April 20, 2008, http://www.pchrgaza.org/files/PressR/English/2008/37-2008.html (accessed May 17, 2008).

135 Letter to Human Rights Watch from the office of Prime Minister Ismail Haniya, June 4, 2008.

136 Human Rights Watch interview with Arafat Deeb, Gaza Central Prison spokesman, Gaza City, Gaza Central Prison, October 12, 2007.

137 Human Rights Watch interview with Abdalla Abu Luli, legal affairs director of the Internal Security Force, al-Mashtal detention facility, Gaza City, October 12, 2007.

138 “March 2008 Report,” Palestinian Independent Commission for Citizens’ Rights, March 2008.

139 Human Rights Watch interview with Subhia Juma’a, PICCR, Gaza City, October 10, 2007.

140 Human Rights Watch interview with Jaber Wishah, Palestinian Centre for Human Rights, Jabaliya, October 10, 2007.

141 Letter to Human Rights Watch from the office of Prime Minister Ismail Haniya, June 4, 2008. The punished violations were for three accidental killings, 24 physical attacks, and eight physical attacks on a detainee or prisoner. The punishments for these violations were dismissal, detention or fine. The letter did not specify which punishments were for which offense, or provide other details of the violations.

142 The letter did not specify which principles in the order had been violated, but the punishments were detention (365 cases), salary deduction (115 cases), written pledge not to repeat the violation (82 cases) and dismissal (37 cases). One hundred-seventy five cases were still under investigation.

143 Human Rights Watch interviews with Khadra Khattab and S.K., Deir al-Balah, April 23, 2008.

144 Human Rights Watch interview with H.K., Deir al-Balah, April 23, 2008.

145 Human Rights Watch interviews with S.K., Deir al-Balah, April 23, 2008.

146 Human Rights Watch interview with K.K. Deir al-Balah, April 23, 2008.

147 “PCHR Calls for Investigation into the Death of a Detainee in Gaza Central Prison in Gaza,” PCHR press release, December 16, 2007, http://www.pchrgaza.org/files/PressR/English/2007/175-2007.html (accessed May 21, 2008).

148 “Al Mezan Demands Deposed Government to Investigate Death of Khatab,” Al-Mezan Centre for Human Rights press release, April 15, 2008, http://www.mezan.org/site_en/press_room/press_detail.php?id=831 (accessed May 28, 2008).

149 Human Rights Watch interview with Hussam al-Tawil, Gaza City, May 19, 2008.

150 Human Rights Watch interview with Suad Khatab, Deir al-Balah,April 23, 2008.

151 “PCHR Condemns Excessive and Lethal Use of Force against Civilians in Gaza,” PCHR press release, November 13, 2007, http://www.pchrgaza.ps/files/PressR/English/2007/160-2007.html (accessed May 27, 2008).

152 Human Rights Watch interview with Ihab al-Ghusain, November 14, 2007.

153 Human Rights Watch interview, name withheld, November 13, 2007, Gaza City.

154 Human Rights Watch interview with Y.G., Gaza City, November 13, 2007.

155 Human Rights Watch interview, name withheld, Gaza City, November 13, 2007.

156 Human Rights Watch interview, with A.H., Gaza City, November 13, 2007.

157 Paul Martin, “Bloody Anniversary Wrecks Hopes for Peace Between Gaza Factions,” The Times, November 13, 2007.

158 Human Rights Watch interview with Ihab al-Ghusain, November 14, 2007.

159 Minister of Interior resolution 194/2007.

160 Nidal al-Mughrabi, “Hamas Punishes Policemen for Deaths in Gaza Rally,” Reuters, June 2, 2008.

161 See UN Human Rights Committee, General Comment 31, Nature of the General Legal Obligation on States Parties to the Covenant, U.N. Doc. CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.13 (2004) for how this duty arises in the ICCPR.

162 Human Rights Watch interview with father of victim, Gaza City, October 14, 2007.

163 Medical report, Al-Shifa Hospital, signed Dr. Haza I. Abed, October 8, 2007.

164 Human Rights Watch interview with E.M., Gaza City, October 8, 2007.

165 Human Rights Watch interview with Yusif Mohamed Abu Hussein, Gaza City, October 10, 2007.

166 Human Rights Watch interview with B.R., Khan Younis, November 10, 2007.

167 Human Rights Watch interview with Alla Yassim Abu Awad, Gaza City, October 10, 2007.

168 Human Rights Watch interview with H.S., Khan Younis, October 11, 2008.

169 Human Rights Watch interview with F.B, Khan Younis, October 11, 2008.