Right to an Effective Remedy and Accountability

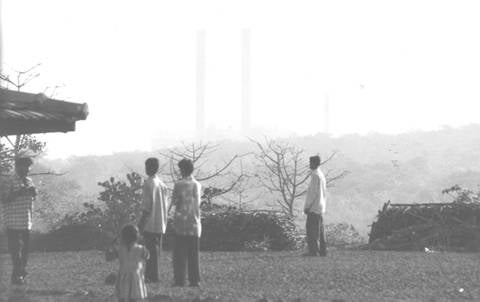

Residents of Katalwadi village in India stand near Enron’s Dabhol power plant (in the background). When some villagers protested against the power plant, contractors for the company and police retaliated against them. © 1999 Arvind Ganesan

Victims of human rights abuses are entitled to an effective remedy that offers redress for the harm suffered. This can encompass, among others, the right of access to courts, the right to a fair trial, the right to equal protection under the law, the right to seek reparation and satisfaction, and the right to enforcement of judgments.97

These rights of victims, however, are rarely upheld against the interests of powerful companies. In many cases, governments fail even to provide the means to hold business actors accountable (such as by failing to ensure the requisite legislation exists). Governments may also fail to enforce existing laws or regulations that would in practice help to protect human rights. In some cases, businesses use their political and economic clout to ensure government inaction.

The various reports touched on above contain examples of obstacles to justice faced by victims of business-related abuses. Two examples are explored here in more detail.

A Job or Your Rights: Continued Sex Discrimination in Mexico’s Maquiladora Sector98

A 1996 Human Rights Watch report on Mexico showed little government oversight of the maquiladora (export assembly) sector. The government did not enforce domestic prohibitions on sex discrimination and it failed to provide mechanisms for investigation or adjudication of complaints. A voluntary pledge by one US-owned company to stop conducting mandatory employment-related pregnancy testing in its factories also failed to achieve the change sought by the victims: pregnancy-based sex discrimination continued the following year, and the company failed to put in place a concrete plan to monitor compliance with its new policy.

The Enron Corporation: Corporate Complicity in Human Rights Violations99

The example of DPC and its parent company Enron in India, discussed at length above, is also informative. The company was allegedly able to bypass review procedures and secure approvals for the Dabhol project despite overwhelming opposition from area residents and some government regulators because it engaged in corruption and collusion with other officials. Communities faced difficulty getting a fair hearing in the courts in part due to alleged political favoritism shown to the company.

The state government of Maharashtra, which had previously filed a suit against Enron on the grounds of corruption in securing the DPC project, was convinced to reverse its position and drop the claim after a renegotiation of the project with Enron. The terms of the new agreement were in some ways more onerous for the government than the deal it had previously criticized, leading to suspicions that it had been improperly influenced by the company. When villagers, frustrated at their failure to secure effective legal redress, took up protests, company contractors and police retaliated against them for having dared to challenge the company.

Several other Human Rights Watch reports touch on business privileges and the absence of remedies for victims or accountability:

- A company that dumped toxic waste in Cambodia was alleged to have bribed officials at every step in the process, subverting the oversight role that the government should have played.100

- Because of inadequate government oversight, transnational labor agencies in several countries have in effect been given primary responsibility for informing workers about their rights and for responding to cases of abuse, often leaving migrant domestic workers with almost no opportunity for effective redress.101

- Jurisdictional challenges and legal obstacles have meant that few cases have gone forward against private contractors accused of crimes in the Abu Ghraib detainee abuse cases and similar ones in Afghanistan.102

- When contractors in Bosnia and Herzegovina were implicated in sex trafficking, the only punishment they endured was being fired, the very same treatment that DynCorp gave the whistleblowers who exposed the conduct. The contractors were not eligible for prosecution in Bosnia and Herzegovina because the company repatriated them to the United States almost immediately after they came under suspicion. A US law passed in 2000 gave the US government jurisdiction over the contractor employees, but implementing regulations to allow such prosecutions were not adopted until 2006.103

- In Guatemala, regulations governing the actions of private security forces have not been enforced, allowing abuses to be carried out with impunity.104

- In the Dominican Republic, where women were often tested for HIV as a condition of work in violation of national law, private employers continued the abuse with impunity.105

97 See, for example, right to a fair legal process at UDHR, arts. 10, 11, ICCPR, arts. 9, 14, CRC, arts. 12(2), 40, and CMW, art. 18(2-7); right to equality before the law at UDHR, art. 7, and ICCPR, art. 26; right to seek reparation and satisfaction at ICERD, art. 6; and right to an effective remedy at UDHR, art. 8, ICERD, art. 6, ICCPR, art. 2, CAT, arts. 13, 14.

98 Human Rights Watch, A Job or Your Rights, pp. 3, 5, 23-26, 50.

99 Human Rights Watch, The Enron Corporation, see especially, pp. 1-3, 23-24, 29-45, 54-61, 80-82, 99-104.

100 Human Rights Watch, Toxic Justice, pp. 2, 3, 9, 37, 34.

101 See, for example, Human Rights Watch, Help Wanted, pp. 3, 21-22, 52, 84.

102 Human Rights Watch, By the Numbers, pp. 6, 19-20; “Q&A: Private Military Contractors and the Law,” Human Rights Watch questions and answers; “US: Close Legal Loopholes Allowing Contractors to Act with Impunity,” Human Rights Watch news release, October 2, 2007, http://hrw.org/english/docs/2007/10/02/usint17002.htm.

103 Human Rights Watch, “Bosnia and Herzegovina,” in World Report 2003,p. 324.

104 Human Rights Watch, Guatemala's Forgotten Children, p. 47.

105 Human Rights Watch, A Test of Inequality, pp. 1, 17-23.