Labor Rights

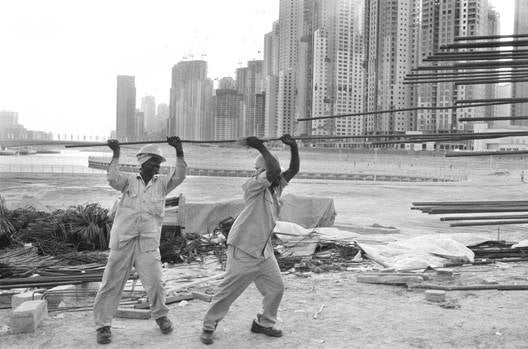

Foreign laborers work to build the Jumeirah Beach luxury apartment complex in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. © 2006 Abbas/Magnum Photos

Labor rights encompass the right to work as well as the enjoyment of rights at work.69 International law recognizes four “core” labor rights: freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining; the elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labor; the effective abolition of child labor; and the elimination of discrimination with respect to employment and occupation.70 Additionally, other economic and social labor rights, including occupational health and safety, compensation in cases of occupational injuries and illness, and minimum wage standards are also reflected in international instruments,71 as are special protections for mothers, pregnant women, and children in the workplace.72

Human Rights Watch has extensively reported on abuses of workers’ human rights in many contexts:

- Employers have used children to carry out dangerous agricultural work in Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, India, and South Africa in violation of international standards, which provide for a minimum age of employment and prohibit hazardous work.73

- A range of industries in China, Ecuador, Guatemala, North Korea, and the United States, among other places, have compromised workers’ freedom of association.74 For example, employers in Ecuador have impeded workers’ organizing drives by taking advantage of legal loopholes that allow the unlimited use of subcontracted labor.75

- Employers and recruiters in Saudi Arabia, South Africa, the United Arab Emirates, the United States, and elsewhere have abused migrant workers.76 In several of those cases, transnational labor recruiters and private labor subcontracting companies have placed migrants in debt bondage, a situation akin to forced labor.77

- Businesses in Brazil, DRC, and India, among others, have practiced forms of servitude and slavery, including forced labor and debt bondage.78

- Human trafficking for forced labor has taken place in many countries, including Bosnia, Greece, Guinea, Japan, Thailand, Togo, and the US.79

- In Indonesia, labor recruitment companies often confine women seeking to migrate to Malaysia for domestic employment at training centers for months prior to their departure, deceiving the women about the type of work they are to perform, the salary they will receive, and the terms and conditions of their work. They also withhold women’s wages while they remain at the training centers. In many cases, the practices amount to trafficking in persons.80

- Companies operating in a variety of different business sectors and a range of countries—including agriculture plantations in El Salvador, construction firms in the UAE, mining companies in DRC, food processing plants in the US, and manufacturing operations in India—have created hazardous working conditions, contrary to their employees’ rights to a safe and healthy working environment.81

- In India, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, and the US, employers have engaged in wage exploitation, such as payment of wages below minimum standards and excessive salary reductions.82

- Employers in the US and the UAE, among others, have forced employees to work long hours, prevented employees from changing jobs, or given misinformation in the hiring process, affecting the right to just and favorable conditions of work, including free choice of work.83

- In the United States, employers have committed labor rights violations in a variety of industries, from retail to manufacturing to agriculture to meat processing to domestic employment in private homes.84

Three cases involving labor rights are discussed in more detail below.

Discounting Rights: Wal-Mart’s Violation of US Workers’ Right to Freedom of Association85

In a 2007 report Human Rights Watch showed how Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., the largest company in the world and also the largest private employer in the United States, relentlessly exploits weak US labor laws to thwart the right of its US workers to form and join trade unions at its 4,000 US stores. Wal-Mart employs a sophisticated and determined strategy to prevent union activity at its US stores and, when that strategy fails, quashes organizing wherever it starts.

The company has sometimes illegally disciplined and fired union supporters. More often, it has resorted to subtle but equally effective tactics to defeat organizing. For example, the company has called the police to stop union representatives leafleting outside its stores, snatched pro-union information from workers' hands and from break room tables, and banned talk about unions. The cumulative effect of Wal-Mart’s panoply of anti-union tactics is to deprive its workers of their internationally recognized right to organize.

In many cases, the company is able to deny its US workers their right to form and join unions without ever violating weak US labor laws. In violation of international standards, US law generally does not require that workers be given the chance to fully inform themselves of their right to unionize. Even when the authorities find Wal-Mart guilty of illegal conduct, the company faces no fines or punitive sanctions under US labor laws, so there is little to deter illegal anti-union activity in the future.

Building Towers, Cheating Workers: Exploitation of Migrant Construction Workers in the UAE86

The United Arab Emirates hosted at least half a million migrant construction workers in 2006 when it was undergoing one of the world’s largest construction booms. These migrant workers faced wage exploitation, indebtedness to unscrupulous recruiters, and working conditions that are hazardous to the point of being deadly. UAE federal labor law nominally offers a number of protections, but employers largely ignore them in the case of migrant construction workers.

According to a 2006 Human Rights Watch report, employers paid construction workers extremely low wages and typically withheld payment for a minimum of two months as “security” to keep them from quitting. In many cases employers also withheld workers’ passports for the same reason, restricting their freedom of movement. Compounding these problems is the fact that employers often fail to pay recruiting and travel fees (which UAE law obligates them to pay), instead forcing workers to pay these costs by incurring extremely high debts in their home countries; in some cases workers have had to work for years just to repay these fees. Some workers are not paid at all for several months at a time. Workers engaged in the hazardous work of constructing high-rises face high rates of injury and death with little assurance that their employers will cover their healthcare needs. Finally, workers in the UAE are denied the ability to organize and bargain collectively, core labor rights that would give them a tool to combat such abuses themselves.

The UAE federal government has done little or nothing to address the troubled working conditions faced by the construction workers. It has failed to create adequate mechanisms to investigate, prosecute, penalize, or remedy breaches of applicable UAE laws. Aggrieved workers are entitled to seek a hearing before the Ministry of Labor, which arbitrates disputes and refers unresolved cases to the judiciary, but arbitration remains a limited option, so much so that government officials have themselves criticized the process as inadequate and in need of urgent reform.

Underage and Unprotected: Child Labor in Egypt’s Cotton Fields87

A 2001 Human Rights Watch report found that each year Egypt’s agricultural cooperatives—which are effectively government entities—hired over one million children between the ages of 7 and 12 to take part in cotton pest management; children form a particularly high proportion of the wage labor force for cotton cultivation in the country. These cooperatives, though formally established as participatory institutions in which membership is mandatory for most farmers, in effect operate as local arms of the agriculture ministry. Most of the children employed by these cooperatives were well below Egypt’s minimum age of 12 for seasonal agricultural work.

Children typically worked 11 hours a day, including a one to two hour break, seven days a week—far in excess of limits set by the Egyptian Child Law. Labor recruitment efforts in both small and large farms targeted children almost exclusively, because their height corresponded to the height of the plants during certain seasons and because it is easier to control children and hire them at a lower wage. Human Rights Watch found that most children in leafworm control work in the cotton fields came from the villages’ poorer families, suggesting a correlation between their families’ economic circumstances and their own willingness to accept seasonal work.

The disproportionate employment by cooperatives of the poorest rural children means that the latter are especially vulnerable to the ill-treatment, long hours, and health hazards associated with combating pests that attack the cotton plant. Although Egypt has adopted its own Child Law, as well as signed the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the cooperatives run by the agriculture ministry continued to perpetrate these abuses.

69 Rather than group labor rights with economic and social rights, as is frequently done elsewhere, we have instead listed rights related to employment under a separate category. The groupings in this report are intended simply to allow for a simplified presentation of various examples and, as emphasized above, should not be read to suggest that the classifications are fixed or that human rights are anything less than interdependent and interconnected.

70 The fundamental labor rights are identified in the ILO's Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work and are enshrined in eight core ILO conventions: ILO Convention No. 138 concerning the Minimum Age for Admission to Employment, adopted June 26, 1973, 1015 U.N.T.S. 297, entered into force June 19, 1976, and ILO Convention No. 182 concerning the Prohibition and Immediate Action for the Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labor, adopted June 17, 1999, 38 I.L.M. 1207, entered into force November 19, 2000; ILO Convention No. 87 concerning Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise, adopted July 9, 1948, 68 U.N.T.S. 17, entered into force July 4, 1950, and ILO Convention No. 98 concerning the Application of the Principles of the Right to Organize and to Bargain Collectively, adopted July 1, 1949, 96 U.N.T.S. 257, entered into force July 18, 1951; ILO Convention No. 29 concerning Forced or Compulsory Labor, adopted June 28, 1930, 39 U.N.T.S. 55, entered into force May 1, 1932, and ILO Convention No. 105 concerning the Abolition of Forced Labor, adopted June 25, 1957, 320 U.N.T.S. 291, entered into force January 17, 1959; and ILO Convention No. 100, and ILO Convention No. 111. These core labor rights are also preserved in various international human rights instruments, including, for example: freedom of association and right to collective bargaining at UDHR, art. 23(4), ICESCR, art. 8(1), and ICCPR, art. 22; elimination of forced or compulsory labor at UDHR, art. 4, and ICCPR, art. 8; elimination of discrimination in remuneration at UDHR, art. 23(2), and ICESCR, art. 7; requirement of minimum working age for children at ICESCR, art. 10(3), and CRC, art. 32; and prohibition of employment of children in hazardous occupations at ICESCR, art. 10(3), and CRC, art. 32.

71 See, for example, right to work at UDHR, art. 23(1), ICESCR, art. 6(1), CEDAW, art. 11(1a), and CPD, art. 27(1); right to free choice of employment at UDHR, art. 23(1), and ICESCR, art. 6(1); right to just and favorable conditions of work at UDHR, art. 23(1), ICESCR, art. 7, CMW, art. 25, and CPD, art. 27(1b); right to just and favorable remuneration at UDHR, art. 23(3), ICESCR, art. 7, and CMW, art. 25; and right to reasonable working hours, paid holidays, and rest and leisure at UDHR, art. 24, and ICESCR, art. 7.

72 See, for example, prohibition on discrimination against women on the grounds of marriage or maternity at CEDAW, art. 11(2); special protection for mothers and children at UDHR, art. 25(2), and ICESCR, art. 10(2); and special protection for children at ICESCR, art. 10(3), and CRC, arts. 32, 36.

73 Human Rights Watch, Tainted Harvest, pp. 2-3, 15-19, 20-22, 24-42, 44, 80-94; Human Rights Watch, Underage and Unprotected, pp. 10-18; Human Rights Watch, Turning a Blind Eye, pp. 3-8, 11, 13-22, 25-27, 49-61; Human Rights Watch, Small Change, pp. 25-40, 53-56, 78-80; Human Rights Watch, Forgotten Schools, pp. 37-38.

74 See, for example, Human Rights Watch, Paying the Price, pp. 10-12, 16-17; Human Rights Watch, Tainted Harvest, pp. 57-59, 65-72; Human Rights Watch, Corporations and Human Rights: Freedom of Association in a Maquila in Guatemala, vol. 9, no. 3(B), March 1997, http://www.hrw.org/reports/pdfs/g/guatemla/guatemal973.pdf, pp. 37-61; Human Rights Watch, North Korea: Workers’ Rights at the Kaesong Industrial Complex, no. 1, October 2006, http://hrw.org/backgrounder/asia/korea1006/, pp. 11-13; Human Rights Watch, Unfair Advantage, pp. 91-243.

75 See, for example, Human Rights Watch, Petition Regarding Ecuador's Eligibility for ATPA Designation, September 2005, http://hrw.org/backgrounder/business/ecuador0905/index.htm, pp. 11-13.

76 See, for example, Human Rights Watch, Bad Dreams, pp. 27-44, 47-53, 57-69, 75-88, 90-105, 108-118; Human Rights Watch, Unprotected Migrants: Zimbabweans in South Africa’s Limpopo Province, vol. 18, no. 6(A), July 2006, http://hrw.org/reports/2006/southafrica0806/southafrica0806web.pdf, pp. 22-50; Human Rights Watch, Building Towers, Cheating Workers, pp. 26-47; Human Rights Watch, Blood, Sweat, and Fear, pp. 105-117.

77 Human Rights Watch, Bad Dreams, pp. 2, 20-24, 45; Human Rights Watch, Help Wanted, pp. 79-80; Human Rights Watch, Maid to Order, pp. 34-37; Human Rights Watch, Building Towers, Cheating Workers, pp. 2, 8-11;.

78 Human Rights Watch, Forced Labor in Brazil Re-Visited: On-Site Investigations Document that Practice Continues, vol. 5, no. 12, November 1993, pp. 3-7, 9-19; Human Rights Watch, The Curse of Gold, pp. 33-34, 48-50; Human Rights Watch, Small Change; Human Rights Watch, The Small Hands of Slavery.

79 Human Rights Watch, Hidden in the Home, pp. 21-22; Human Rights Watch, Memorandum of Concern: Trafficking of Migrant Women for Forced Prostitution in Greece, July 2001, http://www.hrw.org/backgrounder/eca/greece/greece_memo_all.pdf, pp. 10-13; Human Rights Watch, Bottom of the Ladder: Exploitation and Abuse of Girl Domestic Workers in Guinea, vol. 19, no. 8(A), June 2007, http://hrw.org/reports/2007/guinea0607/guinea0607web.pdf, pp. 42-46; Human Rights Watch, Owed Justice: Thai Women Trafficked into Debt Bondage in Japan (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2000), http://www.hrw.org/reports/2000/japan/, pp. 22-24, 25-27, 29-31, 32-46, 58-116; Women's Rights Project (now Human Rights Watch/Women's Rights) and Asia Watch (now Human Rights Watch/Asia), A Modern Form of Slavery: Trafficking of Burmese Women and Girls into Brothels in Thailand (New York: Human Rights Watch, 1993), pp. 38-74; Human Rights Watch, Borderline Slavery: Child Trafficking in Togo, vol. 15, no. 8(A), April 2003, http://hrw.org/reports/2003/togo0403/togo0403.pdf, pp. 8-35; Human Rights Watch, Hidden in the Home, pp. 21-22.

80 Human Rights Watch, Help Wanted, see, for example, pp. 4, 27, 28, 35, 80.

81 Human Rights Watch, Turning a Blind Eye, pp. 16-25; Human Rights Watch, Building Towers, Cheating Workers, pp. 40-45; Human Rights Watch, The Curse of Gold, pp. 54-55; Human Rights Watch, Blood, Sweat, and Fear, pp. 29-47; Human Rights Watch, Small Change, pp. 27-28. See also, Human Rights Watch, Fingers to the Bone, pp. 16-35.

82 CHRGJ and Human Rights Watch, Hidden Apartheid, pp. 86-91; Human Rights Watch, Bad Dreams, pp. 1-3, 20-22, 36-41, 48-50, 52; Human Rights Watch, "Keep Your Head Down": Unprotected Migrants in South Africa, vol. 19, no. 3(A), February 2007, http://hrw.org/reports/2007/southafrica0207/southafrica0207low.pdf, pp. 80-93; Human Rights Watch, Fingers to the Bone, pp. 2, 12-13, 42-48.

83 Human Rights Watch, Bad Dreams, pp. 20-27, 36-38; Human Rights Watch, Blood, Sweat, and Fear, pp. 42-43.

84 See generally, Human Rights Watch, Discounting Rights; Human Rights Watch, Unfair Advantage; Human Rights Watch, Fingers to the Bone; Human Rights Watch, Blood, Sweat, and Fear; Human Rights Watch, Hidden in the Home.

85 Human Rights Watch, Discounting Rights, see especially pp. 5-8, 19, 29-31, 92-93, 125-26, 139-44, 152-54, 161-163.

86 Human Rights Watch, Building Towers, Cheating Workers, pp. 2-14; 26-45, 48-58. See also, Human Rights Watch, The UAE’s Draft Labor Law: Human Rights Watch’s Comments and Recommendations, no. 1, March 2007, http://hrw.org/backgrounder/mena/uae0307/uae0307web.pdf.

87 Human Rights Watch, Underage and Unprotected.