Impacts: A Selection from Reporting by Human Rights Watch

This section analyzes the human rights impacts of business activities by grouping examples and case materials from past Human Rights Watch reports into seven overarching categories rooted in core international human rights instruments:

- Right to security of the person

- Economic and social rights

- Civil and political rights

- Non-discrimination

- Labor rights

- Rights of communities or groups, including indigenous peoples

- Right to an effective remedy and accountability

The clustering of rights under these categories is intended to facilitate an overview of the broad range of rights that are impacted by business activity and does not imply any hierarchy of rights, any rigid division between the rights listed under each category, or indeed that any specific right could only be included under one category. On the contrary, the rights that appear in these different categories remain closely related, and the categories frequently overlap, reflecting the fact that human rights are by nature universal, indivisible, and interdependent. The prohibition against discrimination, to take the most obvious example, is cross-cutting and applies in all of the categories.

Human rights norms at times explicitly provide for protections for particular segments of society such as women, children, migrants, or persons with disabilities.4 These discrete protections have arisen in part as recognition that each of these populations may be particularly vulnerable to abuse or exploitation as a result of marginalization or discrimination. In this report discussion of the rights of women, children, migrants, and persons with disabilities is incorporated or “mainstreamed” into the presentation of business impacts under the various categories identified above. The report retains a distinct category only for communal rights afforded to particular groups, namely minorities and indigenous communities.

The descriptions of rights impacts presented below are offered as illustrations of past occurrences, and not as current accounts of the facts. They are not intended to establish responsibility or assign blame. Rather, they serve as a means to achieving a more complete understanding of the problems that need to be addressed.

Right to Security of the Person

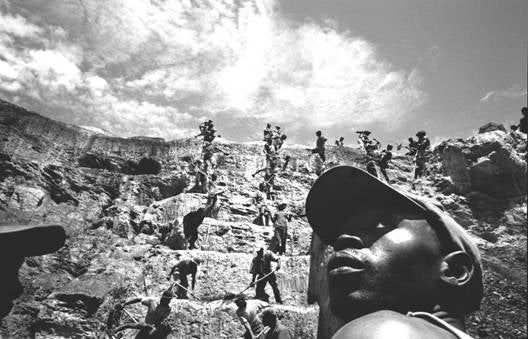

Miners work in the grueling conditions of an open pit gold mine in Watsa, northeastern Congo. © 2004 Marcus Bleasdale / VII

As used here, the term “right to security of the person” refers to the right to life and to physical and psychological integrity.5 Abuses of this right include abuses such as extrajudicial killings, use of lethal or excess force, torture, and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment, including rape and sexual violence.6 Serious and grave abuses of these rights may amount to crimes under international law. Such abuses include war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide, torture, enforced disappearances, rape, and sexual slavery.7

Human Rights Watch’s research demonstrates that business involvement in such abuses arises in a multitude of contexts. Rights in this category have been affected by businesses both directly and through ties to third parties who engage in abusive treatment.

Human Rights Watch research provides numerous, but not exhaustive, examples of direct abuses carried out in a business context:

- Businesses that run or partially staff detention facilities have been implicated in abuses of the right to freedom from ill-treatment, for example, when private US contractors at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq were alleged to have engaged in acts of torture, rape, intimidation, and humiliation of detainees.8

- Companies that produce or trade in products that directly impact human rights, such as antipersonnel landmines, have negatively affected the right to life.9

- Supervisors of female agricultural workers in the US, and of beauticians and domestic workers in Saudi Arabia, have allegedly raped and sexually assaulted workers.10

- Supervisors have beaten children working on Egypt’s cotton plantations and in a multitude of industries in India.11

- Employers have made employees work in conditions that are degrading or life threatening, for example, in US meat and poultry processing plants.12

- Employers have physically abused, psychologically tormented, sexually assaulted, and threatened bodily harm against women and child domestic workers in many counties, including Morocco, Singapore, and the United States.13

In all of these cases, the abuses were accompanied by government failures, at times systemic failures, to protect human rights and ensure that perpetrators were held accountable.

Businesses also can be implicated in abuses through their ties to third parties: if they fail to ensure that their operations do not depend upon, benefit from, or contribute to human rights abuses committed by others, they risk being complicit in those abuses. Situations that can give rise to responsibility for human rights abuses range from outright collusion between the company and the abuser to instances of corporate indifference to human rights. Companies have affected the right to physical and psychological integrity through their ties to security forces, including government security forces as well as private security forces.

Human Rights Watch has reported on numerous incidents associated with company security arrangements, such as the following:

- Companies in Indonesia’s pulp and paper industry have hired private thugs who intimidate or assault members of neighboring communities; government security personnel who receive funding from the companies have assisted or acquiesced in these attacks.14

- Government and private security forces have responded with excessive, sometimes lethal, force against striking workers in China’s heavy industries and protesters demonstrating against a massive power plant in India and oil companies in Nigeria.15

- In Colombia, a variety of businesses—ranging from multinational corporations in agricultural and extractives sectors to local cattle-ranching businesses—have been implicated in killings and other violence against trade unionists through their ties to paramilitary groups.16 In addition, oil companies operating in Colombia have used highly abusive state and private security forces to secure their facilities.17

Companies also have been implicated in abuses by third parties in many other contexts. For example:

- Both public and private arms trading and transport companies in Europe, Central Asia, and elsewhere have provided lethal military equipment to highly abusive governments or armed groups that are subject to arms embargoes or otherwise should be blocked from receiving weapons based on the risk of their misuse.18

- Companies have provided logistical or other support to known human rights abusers that enable more abuses. For example, government forces used oil company infrastructure in southern Sudan to carry out attacks targeting civilians and to wage indiscriminate and disproportionate military attacks that destroyed entire villages and displaced thousands of people.19

Two Human Rights Watch reports addressing the business impacts on the right to security of the person are described in more detail below.

The Curse of Gold: Democratic Republic of Congo20

Local and international business activity has been part of the dynamic of power and violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). A 2005 Human Rights Watch report showed how companies involved in the mining and trading of gold were linked to human rights through their ties to warlords who control goldmines in the northeast corner of DRC. In one case AngloGold Ashanti, one of the world’s largest gold producers, decided to explore for gold in northeastern DRC without adequately considering human rights.

In order to gain access to the gold-rich area, and in return for assurances of security for its operation and staff, AngloGold Ashanti provided logistical, financial, and political support to a murderous armed group that controlled the area. The company did so at a time when it was widely known that the armed group was responsible for grave abuses, including war crimes and crimes against humanity. The group, led by a brutal warlord, flaunted its guns in the streets, forced people to work in the gold mines in miserable conditions, and conducted killing sprees and used torture in nearby villages.

The company had in place a corporate code of conduct that included human rights standards and made public commitments to corporate social responsibility, but in developing ties with the Congolese warlords the company failed to uphold its own business principles to ensure that its activities did not adversely affect human rights.

The business activities of a set of companies that purchased gold mined in DRC also affected human rights, providing a revenue stream for the abusive armed groups. A network of smugglers illegally funneled gold out of DRC to Uganda, where it was bought by multinational companies in Switzerland and elsewhere. The companies that purchased gold from this network knew, or should have known, that it came from a conflict zone in DRC where human rights were being abused on a systematic basis.

One Swiss company, Metalor, claimed it actively checked its supply chain to verify that acceptable ethical standards were being maintained, yet bought gold from the network for five years without raising serious questions about its provenance. The proceeds from the international sale of this gold provided local warlords in DRC with the means to gain access to money, guns, and power to perpetuate their reign of terror on local villagers.

Hopes Betrayed: Trafficking of Women and Girls to Post-Conflict Bosnia and Herzegovina for Forced Prostitution21

During the conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina from 1992 through 1995, thousands of women and girls suffered rape and other forms of sexual violence. The grim sexual slavery of the war years was followed by the trafficking of women and girls for forced prostitution. As described in a November 2002 report, Human Rights Watch found substantial evidence that employees of a US corporation were involved in human trafficking.

In 1999 DynCorp, a US-based government contractor working under contract with the NATO-led Security Forces (SFOR), repatriated a group of contractors after allegations emerged that the men had “purchased” women from local brothels for the purpose of sexual and domestic slavery. Again in 2000 two DynCorp contractors returned home after the US Army Criminal Investigation Division (CID) learned of allegations of the purchase of women and weapons from local brothel owners. The CID investigation uncovered evidence of their involvement in the abuses that violated the women’s right to physical integrity and freedom from torture or other inhumane treatment. In one case, a DynCorp site supervisor was apparently caught on tape raping a woman; in another case, a DynCorp employee withheld the passport of a woman he “purchased.”

When Human Rights Watch looked into these cases in 2002 it found that there had been no prosecutions against DynCorp employees in either Bosnia and Herzegovina or the US for criminal activities related to trafficking. In 2007 the problem of impunity of US government contractors for abuses committed overseas had yet to be adequately addressed, as evident in contractor scandals in Afghanistan and Iraq (addressed further below).

4 For example, CEDAW, CRC, CMW, CPD, and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Persons belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities all address the enjoyment of rights by members of particular groups.

5 The United Nations Human Rights Committee has given the term “security of person” an independent meaning from “liberty and security” to reflects needs of personal security, in addition to the detention issues with which it is frequently associated and which are addressed elsewhere in this report. The use of the term in this report draws on language from Article 3 of UDHR (“Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person”) and Article 5(b) of ICERD (“The right to security of person and protection by the State against violence or bodily harm, whether inflicted by government officials or by any individual group or institution”). UDHR, art. 3; ICERD, art. 5(b).

6 See, for example, right to life at UDHR, art. 3, and ICCPR, art. 6(1); right to security of person at UDHR, art. 3, and ICERD 5(b); right to freedom from torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment at UDHR, art. 5, and ICCPR, art. 7; see also, CAT;CED.

7 See, for example, the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 and their two Additional Protocols of 1977; the Genocide Convention of 1948; the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court; CAT; CED.

8 CHRGJ, Human Rights First and Human Rights Watch, By the Numbers: Findings of the Detainee Abuse and Accountability Project, vol. 18, no. 2(G), April 2006, http://hrw.org/reports/2006/ct0406/, pp. 6, 19-20.

9 The Arms Project of Human Rights Watch (now Human Rights Watch/Arms) and Physicians for Human Rights, Landmines: A Deadly Legacy (New York: Human Rights Watch, 1993), see especially, chapt. 3, “Global Production and Trade in Landmines,” pp. 35-106, and appendix 17, “Antipersonnel Landmine Types and Producers,” unnumbered; and Human Rights Watch, Exposing the Source: U.S. Companies and the Production of Antipersonnel Mines, vol. 9, no. 2 (G), April 1997, http://www.hrw.org/reports/pdfs/g/general/general2974.pdf, pp. 5-7, 9, and appendix A, pp. 12-22.

10 Human Rights Watch, Fingers to the Bone: United States Failure to Protect Child Farmworkers (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2000), http://www.hrw.org/reports/2000/frmwrkr/, p.52; Bad Dreams: Exploitation and Abuse of Migrant Workers in Saudi Arabia, vol. 16, no. 5(E), July 2004, http://hrw.org/reports/2004/saudi0704/, pp. 57-63.

11 Human Rights Watch Children’s Rights Project and Human Rights Watch/Asia, The Small Hands of Slavery: Bonded Child Labor in India (New York: Human Rights Watch, 1996), http://hrw.org/reports/1996/India3.htm, pp. 28-29, and testimonials in chapt. V, “Children in Bondage,” pp. 65-161; Human Rights Watch, Underage and Unprotected: Child Labor in Egypt’s Cotton Fields, vol. 13, no. 1(E), January 2001, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2001/egypt/, pp. 14-15; Small Change: Bonded Child Labor in India's Silk Industry, vol. 15, no. 2(C), January 2003, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2003/india/, pp. 27-28, 34-35.

12 Human Rights Watch, Blood, Sweat, and Fear: Workers’ Rights in U.S. Meat and Poultry Plants (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2005), http://www.hrw.org/reports/2005/usa0105/, see especially, chapt. IV, “Worker Health and Safety in the Meat and Poultry Industry,” pp. 24-56.

13 Human Rights Watch, Swept Under the Rug: Abuses Against Domestic Workers Around the World, vol. 18, no. 7(C), July 2006, http://hrw.org/reports/2006/wrd0706/, pp. 10-13, 16-20; Hidden in the Home: Abuse of Domestic Workers with Special Visas in the United States, vol. 13, no. 2(G), June 2001, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2001/usadom/, pp. 12, 18-19, 21-22.

14 Human Rights Watch, Without Remedy: Human Rights Abuse and Indonesia’s Pulp and Paper Industry, vol. 15, no. 1(C), January 2003, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2003/indon0103/, pp. 32-44, 57-58.

15 Human Rights Watch, Paying the Price: Worker Unrest in Northeast China, vol. 14, no. 6(C), August 2002, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2002/chinalbr02/chinalbr0802-03.htm#P397_85990, pp. 18, 20, 22-25, 31-33; The Enron Corporation: Corporate Complicity in Human Rights Violations (New York: Human Rights Watch, 1999), pp. 99-105; The Price of Oil: Corporate Responsibility and Human Rights Violations in Nigeria’s Oil Producing Communities (New York: Human Rights Watch, 1999), http://www.hrw.org/reports/1999/nigeria/, pp. 9-12, 123-124, 152-154.

16 Letters from Human Rights Watch to British Petroleum Company Plc. (now BP), Occidental Petroleum Corporation, and Ernesto Samper, then president of Colombia, April 1998, http://www.hrw.org/advocacy/corporations/colombia/; Maria McFarland Sánchez-Moreno, Esq., principal specialist on Colombia at Human Rights Watch, testimony before the US House of Representatives Committee on Foreign Affairs, Subcommittee on International Organizations, Human Rights, and Oversight, Subcommittee on the Western Hemisphere and the House Committee on Education and Labor, Subcommittee on Health, Employment, Labor and Pensions, Subcommittee on Workforce Protections, June 28, 2007, http://hrw.org/english/docs/2007/07/23/colomb16458.htm.

17 Letters from Human Rights Watch to British Petroleum and Occidental Petroleum, April 1998; Human Rights Watch, “Corporations and Human Rights,” in World Report 1999 (New York: Human Rights Watch, 1999), http://www.hrw.org/worldreport99/special/corporations.html.

18 See, for example, Human Rights Watch, Ripe for Reform: Stemming Slovakia’s Arms Trade with Human Rights Abusers, vol. 16, no. 2(D), February 2004, http://hrw.org/reports/2004/slovakia0204/, chapt. VI, “Arms Exports to Human Rights Abusers,” pp. 43-52; Angola Unravels: The Rise and Fall of the Lusaka Peace Process (New York: Human Rights Watch, 1999), http://www.hrw.org/reports/1999/angola/, chapt. IX, “Arms Trade and Embargo Violations,” pp. 89-141; Afghanistan: Crisis of Impunity—The Role of Pakistan, Russia, and Iran in Fueling the Civil War, vol. 13, no. 3(C), July 2001, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2001/afghan2/, pp. 4, 30-31;Worldwide Production and Export of Cluster Munitions, April 2005, http://hrw.org/backgrounder/arms/cluster0405/, pp. 3, 12-14.

19 Human Rights Watch, Sudan, Oil, and Human Rights (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2003), http://www.hrw.org/reports/2003/sudan1103/, pp. 41-42, 65-69, 189, 251-273, 428-429, 434-435, 438-449, 524.

20 Human Rights Watch, The Curse of Gold: Democratic Republic of Congo (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2005), http://hrw.org/reports/2005/drc0505/, pp. 2-3, 58-83, 97-98, 111-117; Lisa Misol, “Private Companies and the Public Interest: Why Corporations Should Welcome Global Human Rights Rule,” in Human Rights Watch, World Report 2006 (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2006), http://www.hrw.org/wr2k6/, pp. 4-5.

21 Human Rights Watch, Hopes Betrayed: Trafficking of Women and Girls to Post-Conflict Bosnia and Herzegovina for Forced Prostitution, vol. 14, no. 9(D), November 2002, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2002/bosnia/Bosnia1102.pdf, pp. 5-6, 50, 62-68; Human Rights Watch, “Bosnia and Herzegovina,” in World Report 2003 (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2003), http://www.hrw.org/wr2k3/contents.html, p. 324.