III. Life of Girl Domestic Workers in Lower Guinea

According to a recent ILO study on child labor in Guinea, based on interviews with 6,037 children, domestic labor is by far the biggest employment sector for children. Of working children 61.4 percent are domestic workers. The majority of them are girls.93 Based on the relative (percentage) figures given in the study, about 1.2 million girls in Guinea are doing domestic work, including those who work for their own parents. The vast majority of children indicated that their work place is their home; it is likely that children working for relatives or other de facto guardians described their work place as the home, too.94 Neither the government nor U.N. agencies have absolute figures on the number of girl domestic workers in Guinea.95

Once girls have arrived at their new host family, the harsh life of a child domestic worker starts. This is particularly the case for the vast majority who live with their employers. Many experience labor exploitation as well as child abuse and neglect. Girl domestic workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch described working excessive hours, carrying heavy weights at a young age, working for no pay, starving while the host family eats, and being insulted, shunned, beaten, sexually harassed and raped.

This is not the case for all girl domestic workers. Living and working away from the family can be a positive experience. Ten-year-old Christine C. prefers living with her cousin in Conakry to living with her mother in the village. She explained:

I was in the household of my cousin in Conakry. I went there when I was small. When my cousin got married, she asked for a girl to be sent to her and help her. So I was sent. When I lived with her, I cleaned the courtyard, fetched water, did the dishes, and washed the laundry. I was well taken care of. They did not have many things; my mom even had to send clothes from here…. My cousin put me into school up to second grade. Then I had to go back to my mother. I had to come back because my mum needed a girl at home. I came back when I was eight or nine years old. My mother is old. I would like to go back to Conakry…. I want to go to school with my girlfriends again.96

Indeed, child fostering can be useful for economic survival, education and socialization. These systems can work well when there is a viable social network of persons monitoring the child’s well-being.

Certain factors increase a child’s vulnerability, and hence the risk of abuse. Girl domestic workers tend to be vulnerable to abuse due to their gender, the absence of their biological parents, and their background from mostly poor rural families. If they do not have at their disposal networks of support, such as continued contact with their parents and integration into other social networks, they are at greater risk of abuse.97 While studies in Africa have indicated that foster children and other non-related children are particularly likely to be kept out of school and experience abuse,98 biologically-related children are not necessarily shielded from neglect and violence by their parents either.99

The double role of employer and guardian

The adults who employ and host girls as domestic workers have a double responsibility as employer and as de facto guardian of a child in their care.

As employers, they have to respect the labor rights of the girls. Children under 15 should not be employed at all; those over the age of 15 have the right to a fair wage, limited working hours, decent working conditions such as proper accommodation, nutrition and health care, rest during the day, weekly rest days and holidays.100

But the role of the host family goes beyond respecting the labor rights of the child. When adults decide to take in a girl as a domestic worker, she is effectively in their care, and they become de facto guardians with the responsibility to respect her rights.

Labor exploitation of girl domestic workers

Some girls become domestic workers so early that they cannot remember the age at which they started. Most of the 40 girls interviewed for this research started domestic work under the age of eight.

Under Guinean law, the general rule is that children under the age of 16 should not be employed and therefore cannot lawfully enter into an employment contract. However, Guinea law makes provision for those under 16 to be lawfully employed if their parents or legal guardians give consent. Such a “claw back” clause in the law effectively undermines any meaningful protection for children under 15, particularly girls who are often sent by their parents to work as domestic workers.101

Whether a girl is over 16, or under 16 and her parents have consented to her employment, where she is required to work full-time in the household beyond what may be reasonably considered light household chores, and even where such work is not coerced, a de facto employment relationship exists. All girls so employed must be afforded their full labor rights. At present, girls of all ages suffer labor exploitation, some of which amounts to forced labor.

Crude exploitation: Work for no or little pay

A recent study of child labor in Guinea by the International Labor Organization (ILO), based on interviews with over 6000 children, also found that “many children work but few are paid.” The study found that 6.8 percent of boys and 5 percent of girls were paid. Children living in Conakry and those over 15 had slightly higher chances of getting paid.102

Most girls interviewed in the course of our research received no salary. Even those who had been promised a salary and given a specific figure frequently did not get paid. Of 40 Guinean and Malian girls interviewed, only ten had received any salary. Of those, five had had jobs in which they were paid the agreed salary in a regular manner; the other five were promised the salary but were only paid at the start, irregularly, or only part of the promised money. Four of the five who did get a regular wage had also held jobs in which they were not paid, irregularly paid, or paid less than had been agreed, including through payment in kind. Usually, girl domestic workers did not have a written contract.

Salaries for 40 girl domestic workers in Guinea

($1 = about 6000GNF, as of May 2007103)

|

Monthly salary |

Number of girl domestic workers104 |

Number that received a regular salary |

|

None |

30 |

-- |

|

Below GNF20,000 (=about $3.33) |

5 |

1 |

|

GNF20,000 – 50,000 (=about $3.33 – 8.33) |

2 |

2 |

|

Above GNF50,000 (more than about $8.33) |

3 |

2 |

|

Total |

40 |

5 |

In many cases, there were no discussions about salary at all. A girl was simply sent to work as child domestic worker for some of the reasons explained above.105 When girls were placed with relatives or other people at a young age, their labor was not considered work worthy of pay; it was just seen as their contribution to family life. In many cases the girls themselves did not ask for a salary and even seemed surprised about the question. Parents and the employers themselves often defined the situation more in terms of child fostering; they did not look at it as child labor. Even when there was a salary paid, the girl was usually not involved in salary negotiations, rather she was told that she was going to get a certain amount. This was the case of 14-year-old Liliane K., who even sent some of her meager income to her mother:

I am from Kissidougou. My father died…. My mother gave me to a woman who was our neighbor. My mother did not have a choice because she did not have money to look after her children. Because of the war, the neighbors wanted to leave Kissidougou and go to Conakry. My mother is still in the village. I was about nine when I arrived here in Conakry. I should normally get GNF10,000 [about $1.60] per month, but sometimes I only get 5,000 or 7,000…. The tutrice says sometimes that she does not have enough money to pay me.… I send some money to my mother. I give it to people who are going to the village. Since I am here, I have been told that my mother suffers a lot. I have never seen my mother or been in contact with her since I came here.106

Child domestic workers can never be sure they will get the promised salary. Justine K. was sent to live with her aunt in Conakry at a young age, but started to work for another family as child domestic worker to escape her situation:

I heard that a family was looking for a girl domestic worker. They offered GNF10,000 [about$1.60] per month.… At the outset, I told them to keep my salary and give it to me every four months. But after the first year, they stopped giving me money and said they would send it to my parents instead. I don’t even think they knew my parents, and my parents told me they never received the money.107

Older girls are slightly more likely to get paid. The ILO found this in its larger study, and it was also the case among the 40 girls interviewed by Human Rights Watch. Six girls interviewed had started working as child domestic workers at the age of 15 or older; five of them had received salaries. For example, Francine B., who found work with a Lebanese-Guinean couple, was paid GNF25,000 (about $4.16) on a regular basis.108 Malian girls also sometimes managed to get jobs where they got a regular salary. In 2002-2003, the High Council of Malians drew up a list of seven Malian girl domestic workers in Conakry; they all received GNF7,500 (about $1.25).109 Three of the Malian girls interviewed at some point received between GNF50,000 and GNF75,000 (about $8.30 and $12.50) and were paid regularly.110 However, these three girls had only arrived at these jobs after having been exploited with no pay in previous jobs, and having received some help from fellow Malians to leave these jobs and find better positions. Nadine T., an 18-year-old Malian domestic worker, explained:

I came to Conakry two years ago. I met a woman at Bamako, Tigira Conde. She said it is good in Conakry. You can earn good money, and go dancing and have fun in Conakry. She sent me to work somewhere for six months. But I did not get a salary. I don’t know if Tigira Conde got any money.… I am now working elsewhere and doing fine there. I am paid GNF75,000 there.111

The Malian community is aware of these problems and has frequently intervened to assist the girls get their salary. In one such case, a young woman in her early twenties was assisted by members of the Malian community to get her salary for about eight years she had worked as child domestic worker without pay. The employer finally paid about GNF800,000 to the woman.112 The Malian High Council has even demanded salary payments when girls were employed below the legal minimum age. In 2004, the High Council of Malians in Guinea identified two such girls, aged, 12 and 13, who had worked as child domestic workers without pay. Leading members of the High Council went to see the employers of these girls; as they refused to pay them, the High Council of Malians threatened to take the family to court. The salary was found to be about GNF800,000 (about $120). The tutrice eventually paid half of what was owed to the girls.113

Payments for intermediaries

In some cases, intermediaries who had recruited a girl from Mali received a portion or all of the salary. Florienne C., whose case is mentioned above, was exploited in that way. She had been told by her intermediary that she could earn GNF25,000 (about $4.16) in Conakry. When she arrived this did not happen:

I worked as domestic worker for one year and three months…. At the end, my tutrice paid the money to the woman in Madina [the intermediary], and she took my money. It was GNF385,000 (about $64). The woman [intermediary] just refused to give me the money. I was sent elsewhere. But after one month I was dismissed. Then, I worked for two years at one place. When my father died, I returned home…. I wanted to have my salary from the two years, but the tutrice decided to pay me in kind.114

Other members of the Malian community confirmed that intermediaries took some of the money paid for the service of child domestic workers.115 According to a Malian girl living in Conakry, they are supposed to take half of the salary and give the other half to the girl herself.116

Most Guinean girl domestic workers interviewed did not know whether intermediaries received any money. However, in two cases the girls knew that their employer was sending money to the person who had sent them. Berthe S., 17 years old, lived with her aunt who sent her to do domestic work at the neighbor’s. Her aunt received Berthe’s monthly salary of GNF30,000 (about $5). In addition, the girl has to do domestic work at her aunt’s place.117 The host of Georgette M. from the Forest Region, whose case is described above, regularly sent shoes or cloth to her mother back in the village.118

There seem to be well-established networks of intermediaries who make money by placing Guinean children as domestic workers. According to a representative of the Ministry of Social Affairs:

There is a woman there who functions as intermediary and places the girls as domestic workers. At the end of the month the tutrices go there and pay this woman some money. She always gets money from placing the girls, while the girls themselves sometimes do not have a salary.119

Types of work

Girl domestic workers carry out a wide range of tasks within the house, as well as outside. They clean the house, wash the laundry, pound rice, maize, or sorghum (millet), prepare food, and do the dishes. They also go to the market to buy food for the family. The task of fetching water from distant wells or other sources is a particularly hard type of work, because of the distances covered, the physical labor involved in lifting and carrying, and the potential threats during the journey. Furthermore, girl domestic workers often look after small children during the day and at night. Some girl domestic workers also have a second, different job; they are employed by the tutrice to sell goods, such as vegetables, eggs, donuts or cigarettes, on the street or in the market. They usually do this towards the end of the day. They are given the products to sell by their employer and expected to hand over the money earned. Domestic workers in the rural areas also sometimes do agricultural work.

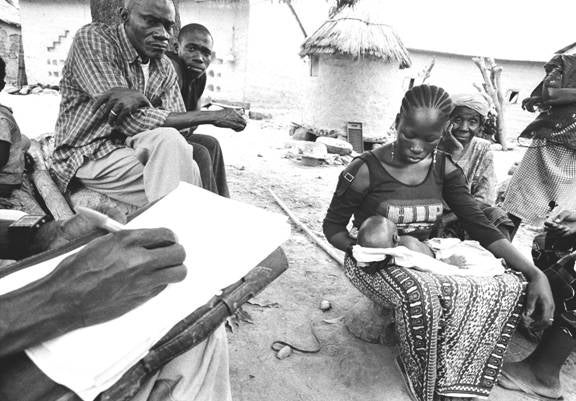

Domestic girl worker washes dishes for her host family before she goes to primary school in Conakry.

© 2007 Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

As mentioned, fetching water has particular hazards. Girls are often overburdened with the weight of heavy containers or buckets. For example, nine-year-old Rosalie Y. told us that she had to carry containers with 20 liters of water every day; she complained this is “too much.”120 Others also complained that they had to carry 15 or 20 liters of water a day. The impact of heavy weight on children’s growth is known; it may lead to skeletal deformation of the back and neck and accelerate the deterioration of the joints.121 In fact, the ILO specifically defines carrying heavy loads as a worst form of child labor.122 Another problem is that water is often only available in the early morning hours, so that girls have to walk deserted paths in the night and are exposed to the risk of assault. Fourteen-year-old Claudine K. started working at age six in her aunt’s house. She told us:

I had to get up around 4 a.m. to fetch water. I had to do this because there is not always water. The whole thing was scary. If I met men or boys, I hid. Once a man told me he that if you don’t stop and sleep with me, I will cut you open. I dropped the water I was carrying on my head and ran. I told my aunt and she said I should go a little later. Then I went around 5 a.m., after the first prayer call.… I was always so tired when she woke me up. Sometimes I would cry when I am woken up.123

Claudine’s situation improved after the Guinean Association of Social Workers (Association Guinéenne des Assistantes Sociales, AGUIAS) decided to help her by speaking with her guardian and enrolling her in primary school. She still has to fetch water, but now goes around 7 a.m.124

Working hours and rest

Child domestic workers rarely have any holidays, no weekly day off, and little rest during the day. They are made to work around the clock and are sometimes beaten when they try to rest or take a break. Several girls testified that they had to work more than 12 hours per day. When asked about working hours, girls sometimes did not count the hours they spent at the market selling goods after completing the household chores in the afternoon. They were de facto doing two jobs, one as a child domestic worker and one as a street vendor. Girls also often omitted their child care duties after they ended other house work; they did not seem to consider these responsibilities to be work. Asked about her working hours, Susanne K. age 16, said:

As a domestic worker, I had to clean the house, cook the food, wash the dishes, and go to the market. I had no breaks. I was the first one to get up and the last one to go to bed. I got up around 4:30 in the morning, with the first prayer call. In the evening I worked sometimes until midnight, while the other children were watching TV.125

Fourteen-year-old Thérèse I. also worked about eighteen hours a day:

I have to get up at 4 a.m. and work up to 10 p.m. I wash the laundry, clean the house, do the dishes, buy things at the market, and look after the children. I am told I get GNF15,000 [about $2.50] per month, but I have never seen that money. Shortly after I came, I fell sick. The lady accused me of faking it and refusing to work. Since that day, I have often been sick but I never say so. I am beaten. When I take too long here, I may be beaten. Whenever I want to take a rest, the lady says I did not come to rest but to work, and beats me with an electric cord or a piece of tire and pulls my ears. It happens as soon as I take a break.126

Food and sleeping arrangements

Parents often send their children to the city because they think they will suffer less from hunger and hard living conditions there. Indeed, some girls reported they were treated like the other children in the family; they would eat together with them and sleep in one bed with them. But for many others, this was not the case. Child domestic workers frequently get less than anyone else in the family. They have to prepare food for the family, and in particular for the children, but they often are not allowed to eat it. Some girls are so hungry that they engage in sex for money or steal money from their host families to buy food. In some cases, food seems to have become the tool with which employers or host adults exert power.

Monique K. lived with her stepmother and did domestic work while all the other children went to school. She ate lunch at home, but was told that “dinner is not for her”; she just had to prepare it for the other children. Other girl domestic workers had similar experiences of being excluded from family meals. Girls reported eating leftovers127 or burnt rice from the bottom of the pot,128 eating one meal a day129 and being told to stop eating.130 One said she was sometimes refused food altogether.131 Fourteen-year-old Habiba C., who lived with her aunt, could not take the hunger any longer:

I had no right to eat breakfast. Instead I had to prepare the sandwiches for the children at school. I so wanted to devour them. But I had no choice. My aunt beat me, with shoes or other things. Sometimes she beat me very early in the morning. Once I revolted against this all. I did not want to go sell things on the street. I had not even had breakfast yet. She forced me to go anyway. I cried…. I was with a man, he did garbage disposal. He wanted sex but I refused. But I was too hungry, so in the end I gave in. I ate well that day. He gave me GNF500 or 1000, I cannot remember. I was six or seven years old. I did not feel OK about it, I did it against my will.132

Domestic girls also often did not have a bed or mat, sleeping instead on the bare floor while others in the family would sleep on beds or mats. Some girls had a pagne–a thin cotton cloth that is wrapped around the body–to lie on, others had nothing at all. They slept in the kitchen, in the living room, in the corridor, on a verandah, or in a shop.133 As a result, they often lacked personal space; the lack of a private room also put them at heightened risk of sexual abuse.

Confinement to the home

While some girl domestic workers have to leave the house to work as street vendors, many others are largely confined to the house. Many said that the only time they ventured outside the house was when they did the shopping at the market. Some guardians prohibited the girls from leaving the house entirely, creating a situation of confinement and lack of social contacts. Laure F., age eighteen, experienced this from an early age:

I was not allowed to leave, so I just ran away for short moments sometimes…. One day a friend came from Anta, and he took me with him, and I stayed at his mother’s house. From there I found a foster family.134

When girls were not allowed to leave the house, they did not know the city and might have been afraid to leave; their ignorance created dependence. For example, Caroline C., age 17, was allowed to sell cigarettes on the street in front of the house, but otherwise she did not leave the house and in her three years in Conakry, had hardly ever left the neighborhood.135 Marianne N. lived with her aunt since she was small. Her aunt, who made her work hard, explained that she would have difficulty finding her way around the city: “She has never left the house except for visits to the market.”136 When Marianne found the situation with her aunt unbearable, she left with the help of the neighbors, the only people with whom she managed to be in contact. Unfortunately her neighbors’ intervention led to further problems as they sent her by herself to Liberia, where she got stranded and raped by a man who pretended to be friendly and put her up for a night.137

As many child domestic workers had very few opportunities to leave the house, they found it hard to make friends and socialize; they were often very isolated. At the age of 11, Justine K. decided to work as girl domestic worker for a family who she did not know, in order to escape her aunt’s house. But it was a miserable experience:

Even the kids could boss me around and send me on errands. I had no friends, and was nearly always in the household courtyard, except when I would go buy things at the market.138

When girls did manage to find friends and build social networks outside the home, they were more likely to escape their situation. As a result, employers often seemed to consider contact with the outside world as a potential risk. One Malian girl remembered:

To celebrate New Year’s Eve I went to the house of M. [member of Malian community] to celebrate with other Malian girls. The next day a girlfriend asked me if she could come with me back to my house, so I went back with her. The lady did not like that and she got angry and chased the girlfriend away. This discouraged me. My friend then told me that she could find another job for me. 139

Inability to end domestic work and forced labor

Many girl domestic workers want to leave, but they find themselves unable to do so. Forced labor, practices similar to slavery, and servitude are work situations in which several abuses are compounded. For instance, if a girl works hard, does not get adequate remuneration and cannot leave work, she is considered to be carrying out forced labor. The use of force or threat of force is often a key element in these situations; the threat of violence or actual use of violence can stop children from leaving the work place. When families do not allow a child to leave the home where they are working, this can amount to forced labor.

Girls who are sent to other families at a young age often do not remember their parents well, nor do they know where they live and how to reach them. Even if their relationship with the host family is difficult, they can simply not imagine living elsewhere. Alice D. was given to her aunt when she was under the age of three. She saw her parents the last time when she was five. She does all the house work, gets no salary, and is beaten regularly. She explained that her only way to leave would be to run away:

I can’t return to my parents because my parents decided that I am ‘for the aunt.’ My aunt hits me if I don’t do all of the work, or even when I want to come to the Center [a local NGO providing training], where I am studying sewing. She beats me with a wooden stick…. I’m ready to leave my aunt today. I’m tired of it. My aunt won’t accept this, but if I decide to leave, I won’t tell her, I’ll just go. I suffer a lot with her. Life there is nothing but working and sleeping.140

Sylvie S. came to Conakry when she was small. As described above, her parents had given her to a woman who visited the village and looked for a child domestic worker. Despite her problems in this household–she is whipped every day and works very hard–she said:

I have never thought about returning to the village. I don’t have contact with my parents. They are farmers. I have not asked to go back. If I could change something I would start an apprenticeship.141

But older girls have similar problems. Caroline C. came to Conakry when she was 14. Through a friend of her mothers, she was placed with a woman for whom she does domestic work. She works hard, has no rest, gets no salary, and is subjected to verbal abuse. She explained:

I have never received a salary. I don’t think my mother’s friend or my parents get money either, because I have not seen my mother’s friend again. Also my parents are probably not getting money because ‘in their mind, I am learning a profession.’… I never discussed payment with the family, because the lady considers that I am with her like that, as if I was at her disposal. I wanted to tell the lady that I want to leave, but I haven’t done it yet. I am afraid to say it.142

Thérèse I., whose case is described above, had also thought about leaving. But this is difficult for her. In tears, she said:

The tutrice does not want me to leave. I would like to leave, but my mother is not in Boke any more. She has gone to Guinea-Bissau. And I don’t know where she is. There are no other family members to go to either.143

Some girls faced threats of violence or violence when they expressed the desire to rest or stop work entirely. Dora T. got in contact with AGUIAS, a local association offering advice, literacy courses and apprenticeships for domestic workers. Initially her aunt agreed that she could split her time between AGUIAS and the home:

But one day when I came back from AGUIAS my aunt refused. She refused to give me food. The next morning she said, if you leave today, you will not be allowed in. You must not go. I left and went to AGUIAS…. After coming back, my aunt chased me away and I stayed with the neighbors. I had an uncle here in Conakry, he is poor and cannot do much, but he begged my aunt to let me go back. So this is how she let me back in again, on the condition that I do not go back to AGUIAS.144

Malian girls generally seemed to have better networks and benefited from the solidarity of their fellow compatriots, who were organized in a local association and frequently took action when they found out about exploitation and abuse. Several of them left exploitative jobs to go home or to find a better job in Conakry.

Lack of access to health care and information

Many girls did not get adequate care when they fell sick. Often, their employer or de facto guardian simply accused them of faking illness, and demanded that they continue working. Few host families actually bought medicine and treated the illness. Many children had to rely on the help of others such as family members or neighbors to obtain medical treatment. Nine-year-old Rosalie Y. stated that she was beaten with a whip when she was tired or sick.145 Dora T., 14 years old, remembers what happened to her when she fell ill:

Once I fell ill, I had malaria. I was taken to hospital and I needed treatment. My aunt refused and said she had no money. Because my cousin intervened in my favor, my aunt finally paid for the treatment.146

In addition, few girl domestic workers get any health education on HIV/AIDS and reproductive rights. The government and several NGOs are running programs on health education for adolescents, including on HIV/AIDS and reproductive rights. They are trying to reach as many young people as possible through radio programs, and through audio CDs that are made widely available to local actors.147

But as most child domestic workers do not have many opportunities to leave the house and participate in education programs or social events, it is hard to reach this group. Two interviewees who had had sexual experiences at a young age did not seem to know about the risks of contracting HIV/AIDS. For example, Claudine K., when told about the importance of using condoms to prevent sexually transmitted diseases, replied that she had only had intercourse once.148 Habiba C. showed similar lack of knowledge.149 However, another girl who was repeatedly raped by her tuteur told us, “I know about the risks but I don’t have a choice.”150

Psychological, physical and sexual abuse

Psychological abuse

Few adults who hire or use child domestic workers interviewed for this report adequately fulfilled their responsibilities to the girls in their care. Many girls described to Human Rights Watch how they felt stigmatized and rejected by their host family; they were insulted, shunned and mocked by the adults who were to care for them. They were frequently kept separate from the children of the host family. They were accused of lying, stealing, sleeping with men, and being lazy.

When asked about her experience, 16-year-old Marianne N. said, “The worst thing was that my aunt took me in and then abandoned me.”151 Several child domestic workers started to cry when talking about their experiences. Habiba C., whose case is mentioned above, said, “I was really proud to do these things [learning to do domestic work]. I did not know then that hell was going to open in front of me.”152 The psychological consequences of life as child domestic worker should not be underestimated. A report by the ILO has found that the psychological health of children in domestic service is sometimes severely affected. Their self-esteem is diminished and they have feelings of helplessness and dependency. This is exacerbated when children are prevented from mixing with other children or other people at all.153

Physical abuse

Corporal punishment of children is common in Guinea. A recent report noted that despite legal safeguards against child beating, there is “no evidence of application to parental corporal punishment” in Guinea.154 A 1999 report of the Committee on the Rights of the Child observed:

Although the Committee is aware that corporal punishment is prohibited by law, it remains concerned that traditional societal attitudes still regard the use of corporal punishment by parents as an acceptable practice.155

Almost all child domestic workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch had horrible experiences of physical abuse. The vast majority of the girls interviewed said that they had been beaten and otherwise physically abused at the hands of de facto guardians and employers. They were beaten with whips, electric cords, belts, sticks, brooms, and other items. Some said that they were beaten on a daily basis. Rosalie Y, nine years old, whose scars on her back were visible, told us:

Sometimes my employers beat me or insult me. When I say I am tired or sick, they beat me with a whip. When I do something wrong, they beat me too…. When I take a rest, I get beaten or am given less food. I am beaten on my buttocks and on my back.156

Brigitte M. from the town of Pamelap near the Sierra Leonean border worked for a woman in Conakry from the time she was about eight years old. She was also beaten regularly and still has a scar on her head from an assault by her employer:

I do the domestic work and sell piment [hot pepper]. When there is money missing, the woman beats me with a broom. Once she hit me on the head, when I was fighting with her child. She took a cooking pot and smashed it against my head.157

Eight-year-old Mahawa B. was beaten so badly that her mother took her back home:

My aunt beat me when I had not fetched enough water with the 20-liter bucket. She also beat me for other things, with a belt. Once I was beaten badly and my mother came and picked me up. I had injuries and my mother saw them.158

A Sierra Leonean girl who was sent as domestic worker to Conakry to escape the war in her home country. A local NGO helped her find a foster family and enrolled her in primary school.

© 2007 Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

A particularly horrible case of physical abuse happened to Julie M. She explained what happened to her in late 2006:

I have had quite a lot of bad experiences. But there is one day that was particularly awful. I had a friend at our neighbors, and Binta [her guardian, pseudonym] also had a friend there. That day, I was in the neighbor’s courtyard, and a witch doctor came because their child was sick. When the witch doctor came, he said that I and the other child domestic worker [at Binta’s] were witches, that we want to eat the child of the neighbor. That shocked Binta who started to cry. She sent me to get some fire from the neighbors for cooking, and when I went there, I started to cry, I took some time, I could not stand this accusation. When I returned to Binta with the fire, she was angry and asked what I had done all that time. She said you have to say the truth and admit you are a witch, she took a knife and threw it at me, it cut my leg. This day has traumatized me. She also took pieces of glass and cut me with that in the leg.… I could not walk and it started to smell. I had to continue working…. The whole neighborhood was shocked about the treatment by Binta. One day it rained and Binta sent me out to fetch water. A friend in the neighborhood called me and suggested to me to run away. I was bare foot but I left anyway.… A woman in the neighborhood helped me and put me in touch with AGUIAS.159

Sexual abuse

Coerced sexual relations are a fact of life in Guinea given vastly unequal power dynamics between the sexes and endemic poverty. The occurrence of survival or transactional sex creates an environment in which a girl’s consent to any form of sex is not generally considered a key factor. In addition, there is a widespread assumption that girls’ attitudes towards sex can be easily manipulated. When aware of the risks of unprotected sex, girls still find it very difficult to get their partners to use condoms.160 Parents and other adults responsible for girls do not usually see it as a legitimate aim to help girls take control of their sexuality, but rather seek to limit and control their sexuality until married. They fear promiscuity, or what is sometimes called délinquance sexuelle and vagabondage sexuel.161 This viewpoint neglects the role of men in initiating sex and dominating sexual relationships, and in forcing sexual relations even where a girl does not offer her consent or explicitly indicates she is not consenting; these situations amount to rape.

Many of the girl domestic workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch described having been sexually harassed, sexually exploited and raped. Fourteen girls spoke about their experiences. Most frequently, they were approached by men living within the household, including the tuteur (the head of household), the household children or extended family members. Some suffered years of continued sexual abuse and saw no means to protect themselves or denounce the perpetrator.

Several girls told us, in tears, that they had been raped by men in the house they were living in. Susanne K., who had already been raped by a truck driver when she tried to go from her village alone to Conakry, related her experience:

When my aunt leaves the house, her husband takes advantage of the situation and has sex with me. When I sleep with my uncle, he does not finish his plate and gives me the remaining food. Otherwise I do eat not very much, and sometimes even nothing. I never get breakfast. A boy in the family also abuses me sexually. The abuse by my uncle and this boy continues.… I wish all my past would just be a dream.162

Brigitte M., who was recruited by her tutrice at a weekly market in Pamelap, had a similar experience:

She [the tutrice] still goes to the weekly market near Pamelap. When she is gone, her husband wakes me up and rapes me. He has threatened me with a knife and said I must not tell anyone. He does it each time his wife travels. I am scared. If I told his wife, I would not know where to live.163

Often, such sexual abuse continues until the girl becomes pregnant, at which point local NGOs and other actors in the community find out about such cases.164 Justine K., now 18 years old, lived with her aunt in Conakry from a young age. She was not happy there, and at the age of 11, she decided to go work as child domestic worker for another family:

The father worked for CBG [Compagnie des Bauxite de Guinée] in Kamsar, but he would come home on weekends. When I was 12, and the wife was out of the house one weekend, he came and found me in the kitchen and told me to come to his room. There he grabbed me and started caressing me. I didn’t say anything, but managed to work my way free and run. But he said that if I didn’t come back he would beat me until I bled, so I came back crying. Then he raped me. This continued until I was about 14 and I got pregnant. It was the father who got me pregnant. I knew it when my period stopped coming, but I didn’t say anything about it. During this time, the father would still come to me for sex. But one day he noticed that my stomach was getting bigger and he told me to get out of the house before his wife came back. The children were away that day. Most of my goods were wrapped up in a pagne [African cloth]. He threw it out the door, pushed me out, and shut the door.165

Several girls were also sexually exploited; that is, they agreed to sex in return for some food, money or clothing. Julie M. was about 11 years old when the husband of the tutrice started to have sex with her. He gave her between GNF500 and 1500 in return.166 Another girl had sex with a gardener at the age of nine or ten, so she could buy a dress.167

Many other girls were sexually harassed. According to a social worker in a local organization, the girls often end up giving in to having sexual relations, because they see no way out.168 Thérèse I. said:

Sometimes when I work, the husband of my tutrice slaps my butt. I have told him that I do not like that. One day he wanted to sleep with me. I refused. I said I cannot do that. So he told me to get out of the house. When the lady came home he told her that I had been sleeping with another boy in the neighborhood. The woman said, ‘Is this what you came for? You will not stay with us.’ She forced me to sleep outdoors that night.169

A 14-year-old Malian girl working as child domestic worker in Conakry was sexually harassed continuously by her employer, a chauffeur, until she decided to go back to her home country.170

In addition to the tuteur, younger men and adolescent boys in the house try to pressure the child domestic workers to have sexual relations with them. Liliane K. managed to put an end to the harassment by her guardian’s son. “One night he came and jumped on me. I screamed and everybody came out running. The tutrice got very angry with her son over this and shouted at him.”171 Other girls also told their guardians about sexual violence and harassment. In some cases this worked, but in others the guardians did not believe them. Fifteen-year-old Yvette Y. had this problem with her guardian:

My uncle’s son is about 20, and he wants to have sex with me in the night and during the day, when I am alone with him in the house. When I refuse or I insult him, he says something bad about me. He says that he has seen me with other boys or that I have lied. I have always refused but he continues to push for it. I have tried to tell my uncle, but he does not believe me. He even beats me when I mention it.172

As this case shows, sometimes the girls who are abused end up being the ones punished. In one case, a Malian child domestic worker burned a man with boiling water who wanted to rape her. As a consequence, she was detained by the Guinean authorities; there was no investigation into the alleged case of attempted rape.173

Fetching water or working as a street vendor also exposed girls to the risk of sexual abuse. Several girls experienced sexual harassment or threats of violence while out on the street. One said, “I fetch water around 5 or 6 a.m. Sometimes some guys approach me. When that happens, I drop the bucket and run away.” 174

Rape and sexual harassment cause a great deal of trauma, and those girls who have suffered sexual assault are often in need of medical and psychological support.175 Yet, health care and psychological support are rarely available for these girls as they have little information about available resources or are not allowed to leave their employer’s house. Unless the few existing services actively reach out to these girls, they are unlikely to be useful to victims of rape and sexual harassment.

Denial of education

Only six of 40 girls and women interviewed attended school while working as child domestic workers. The six girls who did attend school had been enrolled by AGUIAS, an NGO focusing on the plight of girl domestic workers. Frequently, girl domestic workers remained at home, while the biological children of the guardian attended school.

In Guinea, primary education is compulsory and, at least theoretically, free of charge. However, there are significant costs associated with schooling, such as buying learning materials, school uniforms or even a school desk. One study found that fees for books, uniforms, food transport and other costs come to about $238 per school year.176

The right to education is not only an important right in and of itself. It is also an “enabling” right; that is, it enables people to realize their rights in other areas. Studies have shown that girls and women are less likely to be subjected to discrimination, violence, other abuses, and HIV infection when they have received an education.177

In some cases, the guardians had promised to the girls’ parents that they would send them to school. Brigitte M.’s guardian used the promise of education to get her father to agree to the recruitment of his daughter. As soon as they arrived in Conakry, Brigitte M. had to work hard and “the promise of education was never mentioned again.”178 Angélique S., who was sent to work for her parent’s employers and land owners, was outraged and ashamed that she did not get an education:

I wanted to leave because all the other children are going to school, except me. Even the smaller children are going to school. I had enough of that. I was ashamed of not going to school and lied about it. My employers promised that I would go to school. But the woman does nothing for my future. I am not getting a salary. My mother does not get any money either. My mother feels grateful towards them. But my father did not want me to go. My mother came here at some point. She asked the woman whether she is sending me to school. She said she would send me to school soon. Then I told my mother it is not happening, the other children are going to school, and I am staying behind. The tutrice refuses. She wants me to be at the house and do house work.179

Angélique was finally assisted by a local association, Action Against Exploitation of Women and Children (Action Contre l’Exploitation des Enfants et des Femmes, ACEEF), who helped her obtain an apprenticeship as a tailor and negotiated this with her employer.

When the girls were older, the guardians sometimes promised vocational training or an apprenticeship. Caroline C., whose case is mentioned above, came to Conakry at the age of 14. The intermediary who placed her as child domestic worker promised her and her parents that she would learn a profession. However her guardian never followed through on this promise:

The reason I came was to learn a profession, not for money. What bothers me is that I’m not learning a profession. I want to learn hairstyling.180

Whether or not an education or apprenticeship was promised, many guardians took a dismissive attitude towards the girls in their care and usually quickly brushed away such demands. One guardian explained why she did not send her niece to school:

[Marianne] was given to me by my brother, so I would raise her in the city and find her a husband here. I was not told to send her to school, and her siblings in the village also don’t go to school, so why should I?

Some girls were told that there was no money to send them to school or to an apprenticeship. Guardians sometimes agreed to send children to school or allow older girls to start an apprenticeship. However, this was only when local NGOs intervened, and usually required difficult negotiations and financial commitment from the NGO to pay for the costs of schooling or apprenticeship. Often the girls found it difficult to meet the dual expectations that were now placed on them. The deputy head of a primary school explained:

There are sometimes problems with girl domestic workers, when the tutrices do not let them come. There are some who work a lot

Claudine K. has been living with her aunt as a child domestic worker and street vendor since she was about six years old. She worked about 15 hours a day and was regularly beaten. One day the chef de quartier (local authority) told young people to attend a meeting with AGUIAS, who were registering children that were not in school. She sought their help and they enrolled her in primary school, with consent from her aunt. While Claudine’s situation is much improved, attending school is still a challenge for her:

I still live with my aunt. I still do domestic work there, after school. As we have class in the morning and afternoon, sometimes she stops me from coming here [school]. The teacher does not know my problem. I have to finish my domestic work first, so I do my homework late at night or sometimes I don’t do it.

Older girls who apprenticed as tailors, hairstylists, or in other trades reported similar problems. Their guardians would overload them with work so that they could not be on time, or would be too tired.

Christine C., age ten, was one of the few girls who told us that she had been happy to stay with a relative in the city, a cousin, in her case. She attended school in Conakry up to the second grade before her mother pulled her out and made her return to the village.184 Many other girls interviewed expressed the desire to go to school or get an apprenticeship.

Trafficking

The exact scale of the child trafficking problem in Guinea is difficult to determine. There are few reliable statistics, and the lines are sometimes blurred between trafficking and ordinary migration, and between trafficking and labor exploitation. While some observers consider the problem to be widespread, others contend that the trafficking problem is limited. The above-mentioned ILO study on child labor in Guinea found that 22.4 percent of the children interviewed were victims of trafficking.185 Other studies in Guinea186 and Mali187 found that a relatively small proportion of migrant child workers interviewed had actually been trafficked.

As explained above, child trafficking is the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring or receipt of a child for the purpose of exploitation. Hence, trafficking occurs when several elements are compounded: the recruitment; the transport or transfer; and exploitation. Exploitation can include sexual exploitation, forced labor or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, and servitude.

Florienne C., 17, holding her child, came to Conakry at the age of 12 to work as a domestic. She recently returned to her village in Mali with the help of the International Organization for Migration (I.O.M.) and local NGOs. © 2007 Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

Some of the child domestic workers interviewed during the course of this investigation can be considered victims of trafficking. These are some examples of such cases:

- When she was about eight years old, Brigitte M. was given to a woman by her father following the death of her mother and brother. She did all the house work for no pay and was frequently beaten. In addition, the male guardian raped her regularly. She slept on the verandah and ate leftovers. She said she would like to leave but did not know where to go; she did not know if her father was still alive.

- At a young age, Laure F. was given to a friend of her father to live and work as a domestic. She had to work from early morning to night. She was given no regular salary, though she was occasionally given a little money. She was beaten regularly, particularly when her guardian found that she had not finished her work. She was treated differently from the guardian’s children; she had to sleep on the floor and was not sent to school. She was not allowed to leave.

- At the age of 12, a woman took Thérèse I. to work for her sister. There, she had to work about 18 hours a day. She did not receive a salary and was beaten regularly, particularly when she tried to rest. She did not receive sufficient food and was sexually harassed by the head of household. She wanted to leave but believed that her guardian would not allow her to leave. Her mother had left the country and Tèrèse knew of no relatives to go to.

- Mariame C., a 14-year-old Malian girl, was approached by a woman in Bamako who told her she could earn more money in Conakry. She was sent to Conakry with another Malian girl. The woman who recruited them worked with a driver, who took them to their work places in Conakry. Mariame C. worked without pay and was sometimes refused food.

- When Florienne C., a 12-year-old Malian girl, went with a woman recruiter and three other girls from Bamako to Conakry. The recruiter sent her to work for a family in Conakry. She worked at a household for one year and three months, but was kicked out after fighting with the sister of the guardian. She was not given her pay, which seems to have been kept by the intermediary in Conakry. She was then sent to work elsewhere for two years. When she wanted to leave, her guardian refused to pay her and only paid her in kind.

While trafficking is a serious and complex human rights abuse, it is one end of a spectrum of broader problems of child protection. Many girl domestic workers in Guinea are not trafficked, but suffer from labor exploitation, physical abuse, sexual exploitation, lack of education and gender discrimination. Policy measures should be based on a broader child protection perspective to prevent and respond to the full range of abuses, not only focus on trafficking. This concern has been voiced aptly by a study on child trafficking and migration in the region:

In our view, immediate action is required to improve the working and living conditions for all working children, both to enhance their quality of life and to make them less vulnerable to abuse, disease, and tempting job proposals in their arena of work, as well as to make them less vulnerable towards traffickers looking to exploit them…. It is our firm belief that children in West Africa will benefit more from policies and actions developed in accordance with this recommendation than from priorities more narrowly focused on the elimination of trafficking.188

Uncertain future: What girls do after ending domestic service

Girls end domestic service in many ways. Some girls are called back by their families, for example, because there have been problems with the employer family. When these girls return to the village, their parents often try to get them married quickly, even if they are still under the age of eighteen; girls may be married as young as eleven.189 Many of the marriages are arranged. Several Malian domestic workers explained that they would marry immediately upon return from Guinea.190 A staff member of the Malian embassy even encouraged the father of a Malian domestic worker to do so, as he seemed to consider this a safe and honorable solution.191 Marianne N., whose case was mentioned above, suffered serious problems as a girl domestic worker. After her failed escape to Guinea, and the birth of her baby born as a result of rape, she was sent back to her family, where she has since married.192

Girls in the city might get married as well, but they can more easily influence the choice of partner and time frame. They might also try to get an education, or the older ones might try to get apprenticeships. Many former child domestic workers do apprenticeships in areas that are seen as “women’s” work, such as tailoring and hairdressing. These jobs seem to be considered as carrying less status; there also seems to be such a large number of tailors and hairdressers that many will inevitably be unemployed.

Two former domestic workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch work currently as sex workers, called filles libres in Guinea. Stéphanie S., 23 years old, worked as domestic worker between the ages of 15 and 19. While she was initially paid well, her employer later refused to pay her full salary, and she had frequent conflicts with the tutrice. She finally left that position and started to sell fish and hamburgers at Kilomètre Trente-Six, an urban agglomeration that serves as a stop-off for most road trips in and out of Conakry. Later, she decided to do sex work.193 Another fille libre explained that she had worked for no pay as a domestic worker before starting to have her own small business selling shoes.194 However, it does not seem that exploitation in domestic service is an important factor in becoming a sex worker. A study by Population Services International on sex workers in Guinea found that most girls and young women became sex workers after they had experienced divorce, separation or death of their husband. Many others had difficult relations with their own family.195

93 Guinée Stat Plus / BIT, “Etude de base sur le travail des enfants en Guinée,” p.7-8. p.49.

94 Guinée Stat Plus / BIT, “Etude de base sur le travail des enfants en Guinée,” p.52-53.

95 Human Rights Watch interviews with Ministry of Social Affairs and UNICEF officials, December 2006.

96 Human Rights Watch interview with Christine C., age 10, Forécariah, February 7, 2007.

97 Fafo Institute of International Studies, “Travel to Uncertainty,” p.7-11.

98 Human Rights Watch, Letting them Fail. Government Neglect and the Right to Education for Children Affected by AIDS, vol. 17, no. 13(A), October 2005, http://hrw.org/reports/2005/africa1005/africa1005.pdf; UNESCO, “Confiage scholaire en Afrique de l’Ouest, Background paper prepared for the Education for All Global Monitoring Report,” 2004/ED/EFA/MRT/PI/58, 2003, http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001468/146879f.pdf (Accessed March 15, 2007), p.22-25; Sonia Bhalotra, “Child Labor in Africa,” OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, 4, April 2003, http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/28/21/2955692.pdf (Accessed May 4, 2007).

99 Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro, World Report On Violence Against Children (New York: United Nations 2006), http://www.violencestudy.org/IMG/pdf/3._World_Report_on_Violence_against_Children.pdf (Accessed May 7, 2007), p.45-107.

100 Minimum Age Convention, art. 2, http://www.ohchr.org/english/law/ageconvention.htm (Accessed March 21, 2007). Guinea ratified the Minimum Age Convention on June 6, 2003. See also Chapter IV on “The Legal Framework,” below.

101 For details, see also Chapter IV on “The Legal Framework,” below.

102 Guinée Stat Plus/ Bureau International du Travail, “Etude de base sur le travail des enfants en Guinée,” p.56. Children subjected to the worst forms of child labor also had a better chance of getting paid. For the definition of “worst forms of child labor,” see Chapter IV on “The Legal Framework.”

103 This the de facto exchange rate in Guinea, due to inflation. The official exchange rate cited by www.xecom is US$1 to GNF3430.25, http://www.xe.com/ucc/convert.cgi (Accessed May 9, 2007). This report uses the realistic exchange rate of US$1 to GNF6000.

104 When girls had multiple jobs, this table shows the highest salary range they received. For example, Michèle T. had two jobs; she was not paid in the first job but received 75,000GNF in her second job and is therefore here represented in the category “above 50,000GNF.”

105 See Chapter I, “Poverty and economic crisis” and “Gender roles and unequal access to education.”

106 Human Rights Watch interview with Liliane K., age 14, Conakry, December 8, 2006.

107 Human Rights Watch interview with Justine K., age 18, Conakry, December 6, 2006.

108 Human Rights Watch interview with Francine B.., age 18, Conakry, December 8, 2006.

109 List of seven cases of Malian domestic workers in Conakry, September 2002–November 2003, on file at Human Rights Watch.

110 Human Rights Watch interviews with Carine T., age 22, Nadine T., age 18 and Vivienne T., age 17, Conakry, February 8, 2007.

111 Human Rights Watch interview with Nadine T., age 18, Conakry, February 8, 2007.

112 Human Rights Watch interview with young Malian woman in Conakry, February 9, 2007.

113 Human Rights Watch interview with female member of the High Council of Malians, Conakry, December 8, 2007.

114 Human Rights Watch interview with Florienne C., age 17, Conakry, February 8, 2007.

115 Human Rights Watch interview with Deputy Head ofthe High Council of Malians, Conakry, February 6, 2007.

116 Human Rights Watch interview with young Malian woman in Conakry, February 9, 2007.

117 ACEEF interview with Berthe S., Forécariah, age 17, February 7, 2007.

118 Human Rights Watch interview with Georgette M., age 16, Conakry, December 7, 2006.

119 Human Rights Watch interview with Ramatoulaye Camara, Director of Children at Risk Unit, Conakry, December 7, 2006.

120 Human Rights Watch interview with Rosalie Y., age 9, Forécariah, February 7, 2007.

121 World Health Organization, “World Water Day 2001,” http://www.worldwaterday.org/wwday/2001/report/ch1.html (Accessed April 3, 2007)

122 See Chapter IV on “The Legal Framework.”

123 Human Rights Watch interview with Claudine K., age 14, Conakry, February 8, 2007.

124 Ibid.

125 Human Rights Watch interview with Susanne K., age 16, Conakry, December 6, 2006.

126 Human Rights Watch interview with Thérèse I., age 14, Conakry, December 8, 2006.

127 Human Rights Watch interview with Brigitte M., age 15, Conakry, December 6, 2006.

128 Human Rights Watch interview with Justine K., age 18, Conakry, December 6, 2006.

129 Human Rights Watch interview with Dora T., age 14, Conakry, February 5, 2007.

130 Human Rights Watch interview with Thérèse I., age 14, Conakry, December 8, 2006.

131 Human Rights Watch interview with Mariame C., age 13, Conakry, February 8, 2007.

132 Human Rights Watch interview with Habiba C., age 14, Conakry, February 8, 2007.

133 Human Rights Watch interviews with girl domestic workers, Conakry and Forécariah, December 2006 and February 2007.

134 Human Rights Watch interview with Laure F., age 18, Conakry, December 8, 2006.

135 Human Rights Watch interview with Caroline C., age 17, Conakry, December 7, 2006.

136 Human Rights Watch interview with guardian of Marianne N., age 16, Conakry, December 6, 2006.

137 See Chapter II, “Risks connected to travel”; Human Rights Watch interview with Marianne N., age 16, Conakry, December 6, 2006.

138 Human Rights Watch interview with Justine K., age 18, Conakry, December 6, 2006.

139 Human Rights Watch Interview with Michèle T., age 20, Conakry, February 8, 2007.

140 Human Rights Watch interview with Alice D., age 17, Conakry, December 6, 2006.

141 Human Rights Watch interview with Sylvie S., age 13, Conakry, December 7, 2006.

142 Human Rights Watch interview with Caroline C., age 17, Conakry, December 7, 2006.

143 Human Rights Watch interview with Thérèse I., age 14, Conakry, December 8, 2006.

144 Human Rights Watch interview with Dora T., age 14, Conakry, February 5, 2007.

145 Human Rights Watch interview with Rosalie Y., age 9, Forécariah, February 7, 2007.

146 Human Rights Watch interview with Dora T., age 14, Conakry, February 5, 2007.

147 Human Rights Watch interview with representative of Population Services International, Conakry, February 4, 2007.

148 Human Rights Watch interview with Claudine K.., age 14, Conakry, February 8, 2007.

149 Human Rights Watch interview with Habiba C., age 14, Conakry, February 8, 2007.

150 Human Rights Watch interview with Brigitte M., age 15, Conakry, December 6, 2006.

151 Human Rights Watch interview with Marianne N., age 16, Conakry, December 6, 2006.

152 Human Rights Watch interview with Habiba C., age 14, Conakry, February 8, 2007.

153 International Labor Office Geneva, Helping Hands or Shackled Lives? Understanding Child Domestic Labor and Responses to it (Geneva: International Labor Organization, 2004), p.51, http://www.ilo.org/public/english/standards/ipec/publ/download/cdl_2004_helpinghands_en.pdf (Accessed March 22, 2007).

154 Global Initiative to End all Corporal Punishment of Children, “Ending legalized violence against children, Global Report 2006,” 2006, fn. 54, p.46, http://www.endcorporalpunishment.org/pages/pdfs/GlobalReport.pdf (Accessed April 4, 2007).

155 UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, “Considerations of Reports Submitted By States Parties Under Article 44 of the Convention, Concluding Observations: Guinea,” CRC/C/15/Add.100, May 10, 1999, http://www.unhchr.ch/tbs/doc.nsf/(Symbol)/CRC.C.15.Add.100.En?OpenDocument (Accessed April 4, 2007).

156 Human Rights Watch interview with Rosalie Y., age 9, Forécariah, February 7, 2007.

157 Human Rights Watch interview with Brigitte M., age 15, Conakry, December 6, 2006.

158 Human Rights Watch interview with Mahawa B., age 8, Forécariah, February 7, 2007.

159 Human Rights Watch interview with Julie M., age 13, Conakry, February 8, 2007. Accusations of sorcery against unwanted children are also known from the Democratic Republic of Congo. See Human Rights Watch, What Future? Street Children in the Democratic Republic of Congo, vol. 18, no. 2(A), April 2006, http://hrw.org/reports/2006/drc0406/drc0406web.pdf.

160 Nancy Luke and Kathleen M. Kurz, “Cross-Generational and Transactional Sexual Relationships in Sub-Saharan Africa: Prevalence of Behavior and Implications for Negotiating Safer Sexual Practices,” September 2002, p.28., http://www.icrw.org/docs/CrossGenSex_Report_902.pdf (Accessed May 8, 2007); Ministère de l’Enseignement Pré-universitaire et de l’Education civique, “Etude sur la violence scolaire et la prostitution occasionelle.”

161 Direction Nationale de l’education pré-scolaire et de la protection de l’enfance (DNEPPE)/ UNICEF, Etude: Exploitation sexuelle des filles domestiques, August 2005, p. 27.

162 Human Rights Watch interview with Susanne K., age 16, Conakry, December 6, 2006.

163 Human Rights Watch interview with Brigitte M., age 15, Conakry, December 6, 2006.

164 Human Rights Watch interview with AGUIAS staff, Conakry, December 8, 2006; Human Rights Watch interview with Deputy Head of the High Council of Malians, Conakry, February 6, 2007.

165 Human Rights Watch interview with Justine K., age 18, Conakry, December 6, 2006.

166 Human Rights Watch interview with Julie M., age 13, Conakry, February 8, 2007.

167 Human Rights Watch interview with Claudine K., age 14, Conakry, February 8, 2007.

168 Human Rights Watch interview with AGUIAS staff, Conakry, December 8, 2006.

169 Human Rights Watch interview with Thérèse I., age 14, Conakry, December 8, 2006.

170 Human Rights Watch interview with young Malian woman in Conakry, February 9, 2007.

171 Human Rights Watch interview with Liliane K., age 14, Conakry, December 8, 2006.

172 Human Rights Watch interview with Yvette Y., age 15, Conakry, December 8, 2006.

173 Human Rights Watch interview with Deputy Head of the High Council of Malians, Conakry, February 6, 2007.

174 Human Rights Watch interview with Habiba C., age 14, Conakry, February 8, 2007.

175 UN Secretary General, “In-depth study on all forms of violence against women,” July 6, 2006, A/61/122/add.1, p.47-48, http://daccessdds.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N06/419/74/PDF/N0641974.pdf?OpenElement (Accessed April 5, 2007).

176 Ministère de l’Enseignement Pré-universitaire et de l’Education civique, Etude sur la violence scolaire et la prostitution occasionelle, p.14.

177 Action Aid, “The Impact of Girl’s Education on HIV and Sexual Behavior,” Education and HIV Series 01, 2006, http://www.ungei.org/resources/files/girl_power_2006.pdf (Accessed May 8, 2007); UNICEF, The State of the World’s Children 2007 (New York: UNICEF 2006), p. 1-15, http://www.unicef.org/sowc07/docs/sowc07.pdf (Accessed April 10, 2007).

178 Human Rights Watch interview with Brigitte M., age 15, Conakry, December 6, 2006.

179 Human Rights Watch interview with Angélique S., age 15, Conakry, December 7, 2006.

180 Human Rights Watch interview with Caroline C., age 17, Conakry, December 7, 2006.

184 Human Rights Watch interview with Christine C., age 10, Forécariah, February 7, 2007.

185 Guinée Stat Plus / BIT, “Etude de base sur le travail des enfants en Guinée,” p.75-76.

186 Stat View International, “Enquête Nationale sur le Trafic des Enfants,” The study found that 30 of 2000 children were victims of trafficking (1.5 percent).

187 Castle and Diarra, The International Migration of Young Malians, p.15. The study found that four of 950 children were trafficked.

188 Fafo Institute of International Studies, “Travel to Uncertainty” p. 55.

189 UNICEF, “At a glance: Guinea,” http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/guinea_statistics.html (Accessed March 15, 2007); US Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, “Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – 2006: Guinea,” March 2006, http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2006/78738.htm (Accessed May 1, 2007).

190 Human Rights Watch interviews with Malian girl domestic workers, Conakry, February 9, 2007.

191 Human Rights Watch interview with Berdougou Moussa Koné, Consul at the Malian embassy in Guinea, Conakry, February 5, 2007.

192 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Aїssatou Barry, head of AGUIAS, March 2007.

193 Human Rights Watch interview with Stéphanie S., age 23, Kilomètre Trente-Six, February 9, 2007.

194 Human Rights Watch interview with Elise N., age not given, Kilomètre Trente-Six, February 9, 2007.

195 Population Services International, “Enquête quantitative sur les IST/VIH/SIDA auprès des filles libres en Guinée” (Conakry, December 2005). The study was based on a sample of 435 sex workers.