V. Legal, Policy and Programmatic Responses to Protect Child Domestic Workers

The political and economic context

The Guinea crisis and January–February 2007 protests

President Conté’s presidency has been characterized by authoritarian rule, corruption, lack of respect for human rights and poor development practices. For years, Guineans endured the situation without much protest. This seeming stoicism changed over the past year when Guinea’s two most powerful trade unions organized strikes. The first two strikes took place in February and June 2006, and demonstrated that trade unions were able to lead popular protests with a capacity to paralyze economic activity throughout the country.244

President Conté’s personal visit to Conakry’s central prison to free two close allies held on suspicion of corruption sparked a third protest in January 2007.245 Under the leadership of the trade unions, Guineans took to the streets and this time demanded not only an improvement of their economic situation, but the nomination of a consensus prime minister with the power to form a consensus government.246 Over the course of the strike, security forces made frequent use of excessive and lethal force on unarmed demonstrators. According to the government, 129 people were killed and over 1,700 injured.247 On January 27, as part of a deal to end the strike, the government and the trade unions finally signed an agreement in which the government committed itself to name a new consensus prime minister and agreed to other concessions demanded by the unions, including reduction of fuel and rice prices.248 However, popular fury hit its peak when President Conté broke the accord and named a close ally, Eugène Camara, as prime minister. Further protests rocked the country, and government institutions were occupied and looted by the angry population. The government declared martial law and the army committed further serious abuses against protesters and bystanders across the country.249

A new start

Under serious pressure from within and outside the country, President Conté finally named a consensus prime minister, Lansana Kouyaté, from a short list provided to him by the trade unions. Many observers hope that this career diplomat and expert in development issues will be able to start the long-awaited structural changes that the country needs. In late March 2007, Kouyaté announced the creation of a new government, in which none of the previous power holders were present. In his speech to the nation, he promised to tackle the “catastrophic situation” urgently, prioritizing national unity, the rule of law and better living conditions for ordinary people, particularly youths.250There might now be real opportunity to address structural problems underpinning Guinea’s politics and economy. As of April 2007, Guineans were hopeful that the new government would finally improve their situation.

Donor aid

Some donors have been reluctant to channel funds to Guinea, due to their concerns regarding human rights, governance and corruption. The European Union suspended development funds in 2002 and permanently blocked them in 2003, invoking the Cotonou Agreement, which obliges EU partner states to respect human rights and democracy. It did so following presidential elections that were marred with irregularities.251 However, bilateral donors have not similarly restricted aid. The United States has continued to provide development assistance to Guinea and has been Guinea’s top bilateral donor in recent years. Between 2004 and 2006, US assistance was between about $14 million and $19 million per year.252 The United States considers Guinea a stabilizing force in the region, and there is significant US private investment in Guinea’s bauxite industry.253

After the new government took office in March 2007, the European Union finalized a deal of over €118 million through the 9th European Development Fund (EDF). The EU also committed separate financial support for the parliamentary elections scheduled for June 2007.254 The UN Secretary-General has called upon the international community to increase its economic cooperation with the government,255 and the UN Central Emergency Response Fund immediately released $2.35 million for urgent humanitarian assistance. France has also pledged immediate humanitarian assistance and offered support in the future.256 Provided that the Kouyaté government continues efforts to implement much needed political and economic reforms, donors are likely to start to increase funding for Guinea in the near future.

Policies and programs to protect children from abuse, labor exploitation and trafficking

Despite legal prohibitions, girl domestic workers are regularly subjected to physical and sexual abuse, labor exploitation, and trafficking. Many Guineans regularly break the law not only by employing underage girl domestic workers, but also by subjecting them to sexual and physical abuse, exploitation, forced labor and trafficking. In practice, these abuses almost always go unpunished and are often not even considered crimes. While girl domestic workers are not the only children suffering from these abuses, they are particularly vulnerable due to their gender, the absence of their biological parents, and their background from mostly poor rural families.

Beyond the legal prohibitions, government policies and programs do not effectively protect girl domestic workers against abuses. Guinea, like most African countries, does not have a system of child protection services. The Ministry of Social Affairs has a Direction de l’Enfance which develops and leads child policies, but it is not operational itself. Rather, the Ministry has contracts with Guinean NGOs that carry out some protection activities. NGOs fulfill an extremely important role in providing some protection for child domestic workers, along with other children. However national NGOs cannot currently fill this protection gap. They already carry out many tasks simultaneously with limited human resources, insufficient training and inadequate funding.

When child protection programs are initiated, they are often targeted towards a particular category, such as girls, orphans and vulnerable children (“OVCs”) affected by HIV/AIDS, refugee children, trafficking victims, and child laborers. These programs might include child domestic workers, but unless there is a specific focus in programming on this group, there is also a risk that the needs of these girls will go unaddressed.

Protection against physical and sexual abuse

Corporal punishment and other forms of physical violence against children are prohibited in schools and in the home, but little is done to enforce this. The Ministry of Social Affairs does not have child protection services. However, in extreme cases, its officials have intervened to protect children who were abused and needed to be removed from their environment; they have usually done so with the assistance of local NGOs. The Ministry also keeps a registry of grave cases of child abuse. In one case, where a mother burnt her daughter with boiling water, officials started judicial proceedings to prosecute the mother. 257

Most child protection work is done by national NGOs, with financial support from international donors. They have programs to monitor the well-being of children and intervene in cases of child abuse. Two such groups, AGUIAS and ACEEF, are focused on the situation of girl domestic workers. They have monitoring networks in Conakry, Kindia, Boke and Forécariah (Lower Guinea), Labe and Mamou, (Middle Guinea), Kissidougou and Macenta (Forest Region). They initiate dialogue with the guardians of the girls and attempt to improve their situation in the family. When such dialogue does not work or is impossible, they have also removed girls from employer families and placed them in shelters or foster families, or have assisted with taking them back to their parents or other relatives. During our research, we met many girl domestic workers who had directly benefited from the interventions of AGUIAS and ACEEF. These NGOs had listened to their concerns and worries, provided psychological support, convinced their guardians to allow them to go to school or get vocational training, enrolled them at school or identified a suitable apprenticeship for them, and even removed them from abusive families and placed them in a protective environment. However at present, there is no legal framework to regulate the role and authority of these NGOs working with children. Given the important role the NGOs play, the direct impact their work has for the rights of children and their families, and their de facto provision of a public service to vulnerable children, it is essential that steps are taken to ensure a legal basis for their work and a legal framework within which they can continue to operate. This should complement the role and framework for state child protection services.

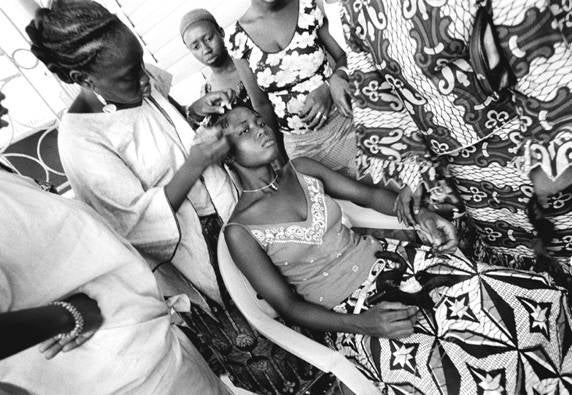

A former domestic worker having her hair braided by other former domestic workers learning to become hairdressers at a training centre run by a Guinean NGO, AGUIAS (Association Guinéennes des Assistantes Sociales). © 2007 Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

Various agencies run programs on women’s rights issues to strengthen the social position of women and girls and help to prevent violence against them. These programs are of great importance for girl domestic workers who are particularly vulnerable to abuse. For example, the Guinean National Coalition for women’s rights and citizenship (Coalition nationale de Guinée pour les droits et la citoyenneté des femmes,CONAG-DCF) documents violence against women, assists women in prison, and carries out awareness-raising activities on early marriage and other girls’ rights concerns.258 In addition, several agencies have programs that provide rapid intervention services, social assistance and rehabilitation services for victims of sexual abuse, and medical treatment. AGUIAS has also recently opened a safe house for women and girls who are victims of sexual or physical abuse, and it has a hotline for victims of sexual violence.259 In the war-affected Forest Region, UNICEF is supporting existing health structures in offering voluntary counseling and testing for HIV/AIDS, programs to prevent the transmission of AIDS from mother to child, and other treatment for AIDS patients and victims of sexual violence. UNICEF has also established child protection committees in the Forest Region. The aim of these bodies is to monitor child rights issues at the local level and refer cases or intervene where necessary.260 The committees are composed of local government officials, youth groups, NGOs, education officials, and other members of the local community.261

Child protection does not only comprise physical protection from abuse; it also means psychological support for victims. In March 2007, UNICEF and the Ministry of Social Affairs started a training program for social assistants and medical staff on psychological assistance for victims of trauma across the country. The response of health structures and NGOs to the influx of victims of violence during January and February 2007, highlighted the need for better services:

There was a remarkable good will of health centre and hospital staff, and of NGOs that worked to register cases of victims such as children and raped women for referral. But one could feel the absence of a coordinated and coherent response among all actors in the psychosocial field.262

This statement can be applied to the area of child protection more generally. While current efforts by Guinean and international actors are important, they are not systemic and by no means sufficient to deal even with the most urgent needs of victims of abuse. A particular problem is the issue of foster care and shelters. When children have been removed from an abusive family, they need to be placed in a protective and caring environment. But choosing foster parents and monitoring their conduct is time-consuming and difficult. Shelters usually do not offer long-term care and also need to be monitored carefully.

On the international level, violence against children came into focus during 2006 when the UN finalized its in-depth study on the issue. The study documents violence against children in the home, in schools, at the work place, in care and justice systems, and in the community. It also looks at the plight of child domestic workers and makes detailed recommendations on how to better protect children.263 The UN General Assembly has welcomed the report and called upon states to implement its recommendations.264

Combating child labor

Up to now, the government has lacked the capacity and political will to address the problem of child labor seriously. There is no list of hazardous work that helps guide policies on eliminating all forms of hazardous labor among children. There are labor tribunals, but they are not used by child domestic workers. While their mandate would include this group, few child domestic workers are aware of their rights. The Ministry has labor inspectors, but they rarely inspect places where child labor occurs, and have not taken up the issue of child domestic workers, seemingly because this is not considered a priority. The ILO has assisted the Ministry of Labor in producing a circular on inspecting child labor on plantations with the aim of providing information and guidance on how to monitor child labor.265 However, the situation has not changed thus far. There is an opportunity now for the new government to take the issue more seriously and initiate effective measures to end child labor below the age of 15, and ban all involvement of children in hazardous forms of child labor.

In Guinea, the ILO has recently focused on child labor in agriculture. In the course of its West Africa Commercial Agricultural Project, it has removed 760 children from this type of work.266 In addition, the ILO has played a key role in developing strategies to prevent trafficking in child labor.267 Another important contribution from the ILO is a recent in-depth study on child labor in Guinea. This study for the first time provides detailed statistical information on the proportion of children who are involved in child labor including in the worst forms of child labor, the social background of child laborers, the different types of child labor, trafficking and related issues.268 On the regional level, the ILO has committed itself to prioritizing an end to the worst forms of child labor. At the Eleventh African Regional Meeting of the ILO in Addis Ababa, in April 2007, the ILO developed an action plan around the “Decent Work Agenda in Africa 2007-2015.” It recommends that all African states prepare time-bound action plans by 2008, with a view to eliminating the worst forms of child labor by 2016.269

Several international and national organizations work on the issue of child labor, such as Save the Children, Anti-Slavery International, the Guinean Association for Young Workers (Association des Jeunes Travailleurs), ACEEF and AGUIAS. Recently UNICEF funded a government study on child labor in the mines.270 Anti-Slavery International, a UK-based international NGO, in particular has strong expertise on issues regarding child domestic workers in various parts of the world and has been developing important advocacy tools.271 In West Africa in particular, the organization has developed a Code of Conduct for child domestic workers that is being used by local NGOs to encourage better behavior on the part of employers.272

The US government monitors child labor practices around the world and publishes an annual report with an overview of the situation in individual countries.273 The report helps keep attention on the issue and provide up-to-date information.

International and regional efforts to end trafficking in West Africa

Over the past few years, the Guinean government has initiated measures to end trafficking in the country and in the sub-region. UNICEF, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and various international and national NGOs also play a key role in combating trafficking. However, current anti-trafficking efforts are also fraught with a number of difficulties. In the absence of a rights-based framework and clear guidelines regarding legitimate migration, the current focus on stopping trafficking at and near borders bear the risk of violating the freedom of movement of young people. In addition, current anti-trafficking measures are hampered by several practical and strategic limitations as will be discussed further below.

Various actors

In 2003, the Ministry of Social Affairs commissioned an in-depth study on the problem of trafficking, which has helped inform policy.274 UNICEF has made anti-trafficking work one its priority areas and provides the government with significant financial and technical assistance. For example, UNICEF’s West and Central Africa Regional Office, together with other actors has developed the “Guiding Principles for the Protection of Child Victims of Trafficking” to advise and guide policy and program responses.275 Through collaboration with local NGOs such as ACEEF and Sabou Guinée, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) runs a program for the return and reintegration of trafficked children who have been exploited in Guinea, or who are of Guinean origin.276 UNICEF and other actors, such as the US government and other government donors, also support national NGOs in their efforts to combat trafficking. Much of the identification and assistance work for trafficking victims comes from AGUIAS, ACEEF, Sabou Guinée, and other national associations. In addition, Save the Children, Terre des Hommes and other international agencies provide practical help for victims.

The Mali-Guinea Anti-Trafficking Accord, June 2005

On the regional level, the Malian and Guinean governments signed an anti-trafficking accord in June 2005.277 The accord is ambitious. It foresees a range of measures, such as exchange of information and the creation of a common mechanism for identifying and registering trafficking cases; the elaboration of national action plans; the creation of a fund for trafficking victims; harmonizing trafficking legislation; prosecution of trafficking; programs to increase birth registration; outreach to communities in sending areas; mechanisms for repatriation of trafficking victims; and rehabilitation of victims.278

Since the signing of the accord, the Guinean and Malian governments have remained in regular contact and held a follow-up meeting to assess progress. Further meetings to monitor progress of the implementation are planned.

Both governments have undertaken some important steps to implement the accord. The Malian government has undertaken various activities on its side. These include an information campaign on the need for a travel document for children; the creation of a government coordinating body on trafficking; training on trafficking for security forces, social assistants, labor inspectors and other relevant actors; and repatriation and assistance for trafficking victims.279 It also includes the strengthening and expansion of surveillance committees. These multi-stakeholder local committees, established by the government and UNICEF have been set up in several countries in West Africa280 to sensitize local communities about trafficking and stop potential trafficking victims from leaving, but have sometimes stopped regular migration, as recent studies have pointed out.281

The Guinean government has also initiated some important activities to fight trafficking, though they do not all relate directly to trafficking between Mali and Guinea. A particularly important step was the creation of the Police mondaine, a police unit responsible for investigating crimes of child prostitution, child trafficking, child abuse, as well as so-called matters of public morality, such as prostitution.282 While understaffed and lacking presence in some parts of the country, the Police mondaine have significantly enhanced government capacity to investigate such crimes. This means that more cases of alleged trafficking and child abuse are now before the courts.283 The Police mondaine have also carried out training with security forces at the border on issues around child protection and trafficking. The aim of these activities is to acquaint border officials, social workers and other government representatives in the border areas with the problem of trafficking, provide them with tools to identify trafficking and involve them in prevention work.284 There have been some joint Malian-Guinean border patrols.285 IOM also is currently in the process of planning training on trafficking issues for law enforcement officials, including members of the judiciary.286 Unfortunately, current activities lack an explicit rights framework spelling out the right to freedom of movement, and differences between migration and trafficking. 287

Furthermore, the Guinean government and UNICEF are in the process of creating local child protection committees in Upper Guinea. As mentioned above, such committees already exist in the Forest Region, where they were partly created as a response to trafficking between Liberia, Côte d’Ivoire and Guinea; their aim is to provide child protection on the local level. The government’s plan is to create four such committees in Upper Guinea.288 Given the problematic experience with surveillance committees in other countries and the need for a broader child protection mandate, the creation of committees with a wider child protection mandate seems appropriate.

The Guinean government and UNICEF have also initiated some important sensitization work. Various media such as street theatre, billboards, radio and TV programs are used to reach out to the population and explain the issue of trafficking through simple, non-technical messages.289 Though not solely related to the Mali-Guinea accord, these activities are essential to addressing the problem.

The government has also created a coordinating body, the National Committee Against Trafficking, which brings together officials from Ministries, the police, the judiciary, UNICEF, NGOs and other actors involved in anti-trafficking work. While some actors on the Committee are in regular contact, the Committee itself rarely meets.290At present, the government is also in the process of drafting new legislation on trafficking of women and children. The new law aims to be more specific regarding the needs of children and women; it is also described as part of the process of harmonization of legal standards at the regional level.291

Regional anti-trafficking accord

In July 2006, 26 West and Central African states signed an anti-trafficking resolution292 and action plan293 during a ministerial conference on trafficking, organized by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS). It was the first time that a detailed anti-trafficking program was endorsed by all regional governments. The action plan envisages a wide range of activities, including the ratification of relevant international and regional standards, the development of national policies, the creation of national anti-trafficking committees, the signing of bilateral treaties, the strengthening of surveillance committees, the prosecution of trafficking, and assistance for victims of trafficking. The signatory states also commit themselves to implement the UNICEF Guidelines to Protect the Rights of Child Victims of Trafficking. The action plan foresees annual progress reports from signatories.

The role of the US

In 2000, the US Congress decided to take stronger action regarding trafficking in the US and abroad and adopted the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act.294 The State Department also created a new office, the Trafficking in Persons Office (TIP), which monitors trafficking across the world and annually publishes a report with detailed country chapters.295 A particular characteristic of TIP’s work is the categorization of countries in tiers. The tier rankings indicate the degree to which a country's government meets minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking, as defined in the 2000 Trafficking Act above. Governments of Tier 1 countries fully comply, while governments of Tier 3 countries do not fully comply and are not making significant efforts to bring themselves into compliance with these minimum standards. The US government subjects countries in Tier 3 to sanctions.296 Guinea is currently on Tier 2, which means it does not fully comply with minimum standards to eliminate trafficking but is making significant efforts to do so. However in 2005, Guinea was placed on the Tier 2 Watchlist. The Watchlist serves as a warning that a country might drop to category 3, if it does not undertake significant anti-trafficking measures. It was removed from the watchlist following the signing of the anti-trafficking accord with Mali, and actions related to it. In addition to monitoring trafficking issues in Guinea, and urging stronger action, the US embassy also provides funds for NGO projects and international agencies in this area.297

Challenges

Despite significant efforts to combat trafficking, important challenges remain. First of all, identification of trafficking victims and practical assistance for victims are still difficult. As illustrated above, the government itself has no child protection capacity and therefore mostly relies on NGOs and other actors to bring cases of trafficking and exploitation to its attention. While there are some specific efforts to detect trafficking at the border, there are no such measures inside the country. Internal trafficking is therefore likely to go unnoticed, as would cases of trafficking that have not been found at the border.

Furthermore, collaboration with Malian NGOs and the Malian community in Guinea is limited. This constitutes a potential obstacle to identifying, assisting and repatriating trafficking victims. Thus, when Human Rights Watch sought assistance for several Malian girl victims of trafficking, it turned out that there was little contact between the High Council of Malians and those dealing with trafficking in the government, national NGOs, or the IOM.298

The current anti-trafficking strategy by governments and agencies across West Africa also fails to engage with intermediaries and develop methods to make migration safe; it might potentially even drive migration and trafficking further underground and hence increase risks for children traveling to work.299 There is also a risk that the focus on trafficking only, and not on other forms of labor exploitation, might shift resources away from the broader group of victims of labor exploitation or other child abuse.

Prosecution of child abuse, exploitation and trafficking

A key to child protection is prosecution of crimes against children. If abuses against children are prosecuted and punished, this should act as a deterrent by sending a clear signal as to which acts against children are illegal and that if perpetrators are identified, that they will be held to account. However, so far, there have been no prosecutions of perpetrators of crimes committed against child domestic workers and few prosecutions of perpetrators of crimes committed against other children.

In part, the lack of prosecutions reflects the weakness of the Guinean justice system. The judiciary is not independent of executive power; it is lacking financial means; judicial staff lack training; and there is an insufficient number of lawyers. In addition, corruption undermines the system. It is common that judicial staff expect bribes and that cases are thrown out because a suspect has paid a bribe.300 In some cases, this has led to vigilante violence.301

While there are currently several cases of child abuse pending before the courts, there have been no prosecutions for trafficking or labor exploitation in 2006.302 In previous years, a few cases of trafficking were prosecuted, but no cases of labor exploitation.303 According to an investigating judge at the Court of Appeal there were several prosecutions of sexual violence in 2005 and 2006; however, it could not be verified whether these included crimes against girls.304 There have been no prosecutions of persons exploiting child labor so far.

Improving girls’ access to education

Government and international donors have taken steps to increase the enrollment rate of girls in school in Guinea. Guinea was one of the first countries to join the Education for All Fast Track Initiative in 2002. The Fast Track Initiative is a multi-donor effort aiming to accelerate progress towards one of the Millennium Development Goals, universal primary education for all boys and girls.305 While the enrollment of girls remains low, the situation has steadily improved since 2000.306

In the formal education sector, the government has attempted to improve access to education for girls through a variety of activities, including the construction of new schools in rural areas, awareness-raising, training for teachers on gender issues, awards and scholarships for female pupils, and improvements of the sanitary infrastructure of schools.307 Some schools also provide food rations for female pupils and their families, in order to encourage school attendance.308 The government has also developed a Code of Conduct for teachers; it includes the prohibition of sexual abuse or exploitation of pupils.309

In addition, a key strategy has been the creation of schools outside the formal education system, the Nafa Centres (or “schools for a second chance”). These schools offer primary education and vocational training to children above the normal age of enrollment in three instead of four years. Successful students can cross over into the formal education system and attend secondary school. The schools are almost entirely attended by girls, and 163 of 186 Nafa schools are located in rural areas. They are run in partnership by the Guinean government, UNICEF and local communities.310 However, the government and local communities have not always contributed to the schools as agreed, and this has led to a lack of staff, reduced apprenticeship programs, and lack of equipment among other things.311 At present, less than one percent of applicants actually get a place; UNICEF and the government are planning to expand the number of Nafa schools.312

There have been few efforts targeted at enrolling girl domestic workers in school. This seems surprising, given the focus on ensuring that girls actually benefit from an education, and the extreme difficulty that many child domestic workers have in attending school. UNICEF recently proposed a regional project on school attendance of girl domestic workers; unfortunately this project, with the apt title, “Education for Liberation,” has not yet been funded. Save the Children runs a program for school attendance of disadvantaged children and has enrolled 4,800 children who were exploited or working in hazardous forms of labor; this number included girl domestic workers.313 AGUIAS has helped girl domestic workers get enrolled in school, and both AGUIAS and ACEEF have assisted girls to get apprenticeships. In doing so, these NGOs have changed the lives of many child domestic workers. Human Rights Watch interviewed several girls who expressed great relief at finally getting an apprenticeship or going to school, and who were deeply grateful to the local association that assisted them.

On the international level, the ILO and UN agencies recently created the High Level Task Force on Child Labor and Education to highlight the importance of combating child labor to achieve universal primary education.314 At the April 2007 Africa Regional Meeting the ILO stated in its report that “free and compulsory quality education up to the minimum age for entering employment or work is the most important tool for eliminating child labour.”315 UNICEF is currently preparing a particular project on girl domestic workers and education.316

244 Human Rights Watch, The Perverse Side of Things.

245 “Guinée: Grève générale anti-corruption,” RFI, January 10, 2007, http://www.rfi.fr/actufr/articles/085/article_48793.asp (Accessed April 11, 2007).

246 Human Rights Watch, Dying For Change, p.14; “Politique: Avis de grève générale. Le texte integral en exclusivité,” Guinéenews, January 3, 2007, http://www.guineenews.org/articles/article.asp?num=2007138129 (Accessed March 19, 2007).

247 Human Rights Watch, Dying for Change; International Crisis Group, “Change or Chaos,” Africa Report No.121, February 14, 2007, http://www.crisisgroup.org/library/documents/africa/west_africa/121_guinea___change_or_chaos.pdf (Accessed May 7, 2007).

248 “Le texte intégral des accords entre les syndicalistes et l’Etat guinéen,” Guinéenews, January 28, 2007, http://www.guineenews.org/articles/outils/print.asp?ID=200712854911 (Accessed April 11, 2007). The accord also foresaw that the trial against Sylla and Soumah, the two powerful men suspected of corruption, should be continued without interference from the executive.

249 Human Rights Watch, Dying for Change.

250 “Guinea’s leader names government,” BBC, March 28, 2007, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/6505263.stm (Accessed April 11, 2007).

251 In late 2006, the EU indicated it might start development aid again; this happened after the Guinean government fulfilled one of the conditions imposed by the EU, the licensing of privately owned radio stations; IRIN, “Guinea: EU aid back but social problems remain.”

252 USAID, “Guinea budget,” http://www.usaid.gov/policy/budget/cbj2006/afr/gn.html, (Accessed April 12, 2007).

253 USAID, “Guinea Strategy Statement,” http://www.usaid.gov/gn/mission/strategy/guinea_strategy_statement_2006-08.pdf (Accessed April 12, 2007).

254 “Un don de 7,5 millions d’euros de l’UE pour appuyer les élections législatives de juin 2007 en Guinée,” January 6, 2007, http://www.apanews.net/elect_article.php?id_article=18188 (Accessed April 12, 2007).

255 ”Secretary-General calls for aid for Guinea after accord on new prime minister,” UN News Centre, February 27, 2007, http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=21694&Cr=guinea&Cr1= (Accessed April 12, 2007).

256 “Guinea: Cash for water, sanitation and health,” IRIN, March 2, 2007, http://www.irinnews.org/Report.aspx?ReportId=70495 (Accessed April 12, 2007).

257 Human Rights Watch interviews with Legal Advisor to the Minister of Social Affairs, Conakry, February 5, 2007.

258 Human Rights Watch interview with Nanfadima Magassouba, head of CONAG, and staff member, Conakry, February 9, 2007.

259 It was created by an international NGO, ARC, in 2005, and handed over to AGUIAS in 2006. Human Rights Watch interview with Aïssatou Barry, head of AGUIAS, Conakry, December 5, 2007.

260 UNICEF, “Humanitarian Action Report 2007,” p. 217-220.

261 UNICEF, “Les comités locaux de protection/CLP et son dispositif communaitaire de protection,” undated document; Human Rights Watch interview with UNICEF Child Protection Officer, Conakry, December 5, 2006.

262 “Renforcer – les capacités des travailleurs sociaux,” JMJ Newsroom, March 14, 2007, http://www.justinmoreljunior.net/jmj_newsroom/lire_l_article.html?tx_ttnews%5Bpointer%5D=3&tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=755&tx_ttnews%5BbackPid%5D=46&cHash=31c20ac5a5 (Accessed April 14, 2007).

263 Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro, World Report On Violence Against Children.

264 UN General Assembly, “Resolution 61/146. Rights of the Child,” A/RES/61/146, January 23, 2007, http://www.violencestudy.org/IMG/pdf/A_RES_61_146.pdf (Accessed April 14, 2007). Violence against children has also been a theme raised by the UN in the field. On June 16, 2006, the Day of the African Child, UNICEF in Conakry published an appeal to protect children against physical violence.

265 Human Rights Watch interview with ILO representative, Conakry, February 6, 2007.

266 Ibid.

267 On anti-trafficking measures, see below.

268 Guinée Stat Plus / BIT, “Etude de base sur le travail des enfants en Guinée.”

269 “ILO Urges Africans to Fight Child Labour,” BuaNews, April 27, 2007, http://allafrica.com/stories/200704270200.html (Accessed May 8, 2007); ILO, “The Decent Work Agenda in Africa: 2007-2015,” Report of the Director-General, Eleventh African Regional Meeting, Addis Ababa, April 2007, para. 231, http://www.ilo.org/public/english/standards/relm/rgmeet/11afrm/dg-thematic.pdf (Accessed May 8, 2007).

270 Ministère des Affaires Sociales/ Ministère de l’Emploi, “Etude sur les enfants travaillant dans les mines et carrières,” 2006.

271 Anti-Slavery International, Child domestic workers: A handbook on good practice in programme interventions (London: Anti-Slavery International 2005), http://www.antislavery.org/homepage/resources/child%20domestic%20workers%20a%20handbook%20on%20good%20practice%20in%20programme%20interventions.pdf (Accessed May 7, 2007); Anti-Slavery International, Child domestic workers: Finding a Voice. A handbook on advocacy (London: Anti-Slavery International 2002), http://www.antislavery.org/homepage/resources/AdvocacyHandbookEng.pdf (Accessed May 7, 2007).

272 Anti-Slavery International, “Sub Regional Project on Eradicating Child Domestic Work and Child Trafficking in West and Central Africa. Code of Conduct,” 2004, http://www.antislavery.org/homepage/resources/PDF/Code%20of%20Conduct%20final.PDF (Accessed May 7, 2007).

273 For recent reports, see the website of the US State Department’s Bureau of International Labor Affairs, http://www.dol.gov/ilab/media/reports/iclp/main.htm (Accessed May 7, 2007).

274 Stat View International, “Enquête nationale sur le traffic des enfants en Guinée.”

275 UNICEF, “Principes directeurs pour la protection des droits des enfants victimes de la traite,” 2005.

276 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with IOM representative in Dakar, May 8, 2007.

277 “Accord de Coopération entre le Gouvernement de la République du Mali et le Gouvernement de la République de Guinée en matière de lutte contre la traite des enfants,” June 16, 2005.

278 République de la Guinée, “Présentation Rapport Guinée,” Bamako, November 2006.

279 République du Mali, “Présentation Rapport Mali,” Bamako, November 2006.

280 UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, Child Trafficking in West Africa, p.14-16

281 Castle and Diarra, The International Migration of Young Malians, p.180-185; Joanna Busza, Sarah Castle and Aisse Diarra, “Trafficking and Health,” British Medical Journal, vol. 328, June 5, 2004, p.1369-1371; Dottridge and Feneyrol, “Action to strengthen indigenous child protection mechanisms in West Africa.”.

282 Human Rights Watch interview with Commissaire Bakary, head of the Police mondaine, Conakry, February 6, 2007. Such police forces exist in many countries and are often set up to crack down on prostitution. In Guinea, the focus of this police force is on crimes against children, including child prostitution.

283 See subsection on prosecution, below.

284 Human Rights Watch interview with ACEEF staff, February 2007; Ministère de la Sécurité, Division Police Mondaine, “Atelier de formation de 40 cadres des forces de sécurité et des Assistants sociaux de la région de Kankan,” 2006.

285 Human Rights Watch interview with representatives of the Children at Risk Unit, Ministry of Social Affairs, February 5, 2007; République de la Guinée, “Présentation Rapport Guinée,” Bamako, November 2006.

286 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with IOM representative in Dakar, May 8, 2007.

287 Comité Interministériel de Lutte contre la Traite des Personnes, “Plan d’action national de lutte contre la traite des personnes, en particulier les femmes et les enfants, 2005-2006”; République de la Guinée, “Présentation Rapport Guinée,” Bamako, November 2006; République du Mali, “Présentation Rapport Mali,” Bamako, November 2006.

288 Human Rights Watch interviews with UNICEF child protection officer and with representatives of the Children at Risk Unit, Ministry of Social Affairs, Conakry, February 5, 2007.

289 Human Rights Watch interviews with UNICEF protection officer, Conakry, December 5, 2006 and February 5, 2007.

290 Human Rights Watch interview with embassy official, Conakry, December 5, 2007.

291 Human Rights Watch interview with Legal Advisor to the Minister of Social Affairs, Conakry, December 6, 2006; République de la Guinée, “Présentation Rapport Guinée,” Bamako, November 2006.

292 Conférence ministérielle conjointe CEDEAO/CEEAC sur la lutte contre la traite des personnes, “Résolution sur la lutte contre la traite des personnes,” Abuja, July 6-7, 2007.

293 Conférence ministérielle conjointe CEDEAO/CEEAC sur la lutte contre la traite des personnes, “Plan d’Action conjoint CEDEAO/CEEAC de lutte contre la traite des personnes, en particulier des femmes et enfants en Afrique de l’Ouest et du Centre (2006-2009),” Abuja, July 6-7, 2006.

294 Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act, 2000. Public Law 106-386, October 28, 2000.

295 For the last Guinea chapter, see US State Department, Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, “Trafficking in Persons Report 2006,” p.129-130.

296 US State Department, Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, “Trafficking in Persons Report 2006.”

297 Human Rights Watch interview with US embassy staff, Conakry, December 5, 2006.

298 Human Rights Watch interview with Deputy Head of the High Council of Malians, Conakry, February 6, 2007.

299 Dottridge and Feneyrol, “Action to strengthen indigenous child protection mechanisms in West Africa.”

300 Human Rights Watch, “Guinée,” World Report 2007, December 2007, http://hrw.org/french/docs/2007/01/11/guinea14967.htm.

301 US Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, “Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – 2006: Guinea.”

302 Current cases include the following: a woman in Conakry who is currently under investigation after she allegedly burnt her daughter with boiling water; a marabou in Labe, Middle Guinea, who is detained on accusations of abducting a girl; several cases of alleged trafficking in Nzérékoré, Forest Guinea; and the case of the pastor and school director. Human Rights Watch interview with Legal Advisor to the Minister of Social Affairs, Conakry, February 5, 2007; Human Rights Watch telephone interview with representative of Ministry of Social Affairs, April 18, 2007; Human Rights Watch email communication from Sabou Guinée, April 27, 2007.

303 Human Rights Watch interview with ILO representative, Conakry, February 6, 2007.

304 Human Rights Watch interview with President of the Chambre d’Accusation of the Appeals Court, Conakry, February 6, 2007.

305 République de Guinée, “Projet de requête pour la procedure accélérée en faveur de l’education pour tous,” October 2002, http://www.fasttrackinitiative.org/library/Guinea_Education_Plan.pdf; Education for All Fast Track Initiativ , “About FTI,” http://www.fasttrackinitiative.org/content.asp?ContentId=958;

(Accessed May 8, 2007).

306 Ministère de l’Enseignement Pré-universitaire et de l’Education civique, “Annuaire statistique enseignement élémentaire. Année scholaire 2005-2006,” September 2006, p.24.

307 Human Rights Watch interview with head of the National Committee on Equity in the Ministry of Education, Conakry, February 8, 2007; Women and Girls Education Network in ECOWAS (WENE), “L’Education des filles en Guinée,” October 10, 2006, http://www.wene.org/articles.php?lng=fr&pg=499 (Accessed April 12, 2007).

308 E-mail communication from representative of Education for All Secretariat, Conakry, April 18, 2007.

309 Ministère de l’Enseignement Pré-universitaire et de l’Education civique, “Etude sur la violence scolaire et la prostitution occasionelle,” p.43ff.

310 Human Rights Watch interviews with education specialist at UNICEF, Conakry, December 5, 2006, and with the Coordinator of the National Commission on Basic Education for All, Ministry of Education, February 9, 2007.

311 Save the Children, “Combattre le travail et l’exploitation des enfants à travers l’éducation (CCLEE) en Guinée. Rapport synthèse du diagnostic participatif communautaire dans les cinq districts du projet,” August 2005, p.9-10.

312 Human Rights Watch interview with the Coordinator of the National Commission on Basic Education for All, Ministry of Education, February 9, 2007.

313 Human Rights Watch interview with Save the Children representatives, Conakry, December 4, 2007.

314 Global Task Force on Child Labor and Education for All, Newsletter, 2007.

315 ILO, “The Decent Work Agenda in Africa: 2007-2015.”

316 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with ILO representative, April 20, 2007.