Victim Assistance: Theory and Practice

Colombian legislation provides for a variety of benefits for survivors of landmine incidents. However, these laws contain some serious gaps, which are compounded by various difficulties in accessing the benefits that are provided. Survivors are often unaware of their own rights, and face bureaucratic bottlenecks and resistance in institutions that are supposed to provide or administer the benefits.

Colombian Legislation

Colombian legislation provides for several basic benefits for which civilian survivors of landmine incidents might be eligible:

Lump-sum payments

“Humanitarian assistance” is available to civilians “who suffer damages to their lives [or] serious damage to their personal integrity and/or assets, as a result of acts that take place in the context of the internal armed conflict, such as terrorist attacks, combats, attacks, and massacres, among others.”47 Currently, humanitarian assistance consists of a one-time payment equivalent to approximately US$8,680.48 The request for assistance must be made within one year of the injury, and there are a series of requirements that must be satisfied.49

There is also a one-time payment available to survivors of “terrorist events caused by bombs or explosive artifacts,”50 including landmines, who suffer a “permanent disability.” A permanent disability is a “loss that is not recoverable through rehabilitation of the function of a body part, such that the individual’s ability to perform in the workforce is reduced.”51 Persons who are certified by relevant authorities as having such disability are eligible for a one-time payment of at most the equivalent of US$1,301 (the amount varies depending on the extent of the injury),52 which must be claimed within six months. If, within a year after the event, the injured person has died as a result of the “terrorist event,” the surviving family can claim the equivalent of $4,337.53

Medical care

Survivors of landmine incidents are entitled to have their emergency medical costs, as well as costs of surgery, medication, and rehabilitation covered. Prosthetic limbs are also included, though the law does not specify how frequently prosthetic limbs may be changed.54

Transportation to a medical facility

According to the law, the government is supposed to cover the costs of transporting survivors from the place of the incident to the first place where they receive emergency medical care and, in some cases, to the second medical center to which the survivor is referred.55

Housing

Colombian law provides that government subsidies for housing are available to people whose homes have been damaged as a result of the armed conflict.56

Education

Victims of the armed conflict are also eligible for certain educational benefits and job training from state institutions.57

Poor Enforcement

While on paper Colombia’s victim assistance programs seem relatively good, in practice they present various problems. There are gaps in the law; many survivors, healthcare workers, and local officials are unaware of the available benefits; and even when they do find out about the available benefits, survivors can face serious difficulties in accessing them. As a result, several of the survivors who spoke to us expressed a great deal of frustration with the government’s victim assistance programs.

Despite having lost both hands and part of his eyesight to a landmine, Javier is a painter. However, he cannot afford his own housing and has been living in a shelter for over eight years. © 2006 MMSM/Human Rights Watch.

For example, Javier Pallares de la Rosa, a 31-year-old who works as an artist despite having lost both hands and part of his eyesight, told us that he lives in a shelter run by a private foundation because he has been unable to receive government assistance for housing. “I have been in this shelter for over eight-and-a-half years … I need to get out of here.”58

The following are a few of the most common concerns we heard from survivors and organizations that work with them:

Insufficient assistance

One gap in the law is that the Colombian government does not cover the costs of transportation and lodging for survivors who need to travel for rehabilitation. Mariela Trujillo, who runs a victim assistance project in Medellín for the Colombian Campaign to Ban Landmines, told us that the majority of victims who need rehabilitation have to go to “level 3” hospitals, which are hospitals that offer a wide range of specialties of medical care and are primarily located in major cities.59 As a result, landmine survivors who need rehabilitation or specialized care either have to relocate near the hospital or they travel regularly, often long distances, to the nearest one.

Trujillo works primarily with survivors in the state of Antioquia, where 97 out of 125 municipalities are reportedly affected by landmines or unexploded ordnance.60 The only level 3 hospital in the area is the San Vicente de Paul University Hospital in Medellin, but “many times the victims have no way of getting to the hospital, and it’s not just one time—they have to come many times.”61

As a result, Trujillo’s group, like various other nongovernmental organizations working with landmine survivors in Colombia, tries to help survivors by covering transportation and lodging costs for survivors who have to travel for rehabilitation.62

Financial assistance—which adds up to a total of at most US$9,908—can also end up being far too little for many survivors.63 Because the assistance is provided in a lump sum, after the survivors spend the money, they are left with no financial support.

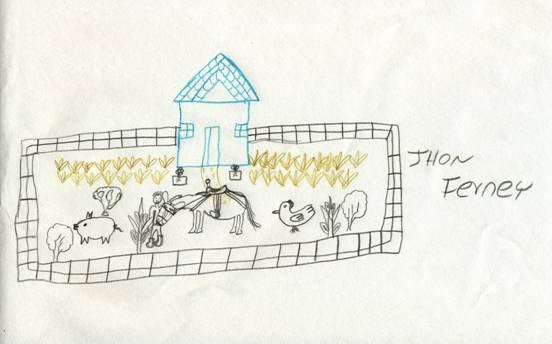

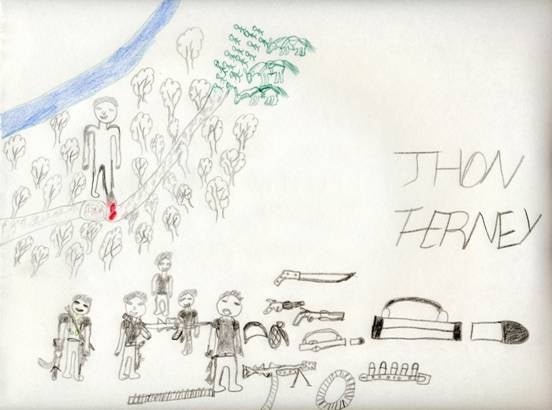

Some survivors are able to invest the sum in ways that allow them to have an income over time. For example, Mauro Antonio Joaquí bought a small house with a storefront in a poor neighborhood on the outskirts of Popayán, and he is able to support himself and his family on the proceeds of the store.64 However, other landmine survivors are not in a position to invest the payments in a profitable manner, either because their needs are so pressing that they must spend the money, or because they lack the skills and knowledge to invest the money. In the case of Jhon Ferney Giraldo, a teenage landmine survivor whose whole family of 14 people was displaced from its farm, the financial assistance that the government provided to him went on the family’s rent and food in Medellín, and the money ran out in just a matter of months.65

Short deadlines and insufficient awareness of landmine survivors’ rights

One serious obstacle, which Colombian government officials themselves acknowledge, is that the law establishes relatively short deadlines for applying for the benefits.66 As noted above, to claim the “humanitarian assistance” the deadline is one year after the events, and to claim the disability payment, the deadline is six months after the incident.67 Meeting these deadlines can be difficult for survivors who are busy dealing with the consequences of their injuries, especially those who do not receive information about the programs in the immediate aftermath of their injuries. As a result, many end up applying for benefits when it is already too late to claim them.68

Survivors are often unaware of the benefits available to them. Moreover, to get the benefits, survivors must fill out complex forms and turn in certifications from local government officials and hospitals that are sometimes difficult to obtain due to local officials’ and hospitals’ lack of knowledge of the law.69 As a result, survivors of landmine incidents often “lose their rights because they don’t assert them,” according to Luz Dary Mesa, a social worker at the CIREC rehabilitation center (Centro Integral de Rehabilitacion de Colombia).70

By law, hospitals are required to provide care to landmine survivors free of charge and to cover the costs of emergency transportation, and then get reimbursed by the government. However, the system does not always work in practice. This is partly due to the fact that local hospitals are not always aware of the law’s requirements, but also because the reimbursement process can be very slow,71 and as a result some hospitals—especially hospitals that are facing financial difficulties—sometimes end up being unable or unwilling to cover patients’ costs.72 Several survivors told us that they had covered their own transportation costs, and Mesa said she had known of cases where the hospital did not treat the patients as landmine victims, or where victims were asked for payments so that the hospital could later reimburse them. To mitigate this situation, Mesa explained, there has to be an effort not only to inform survivors but to create awareness in hospitals.73 Dr. Diana Molina, head of the rehabilitation program at the San Vicente de Paul Hospital also recommended that hospital workers be better trained on landmine survivors’ legal rights and on how to properly bill the state for services provided to survivors, so they can secure reimbursement more easily.74

Hospitals’ lack of expertise in working with landmine survivors can lead to other problems. For example, when they are first admitted, landmine survivors are sometimes referred to experts only for amputations and prosthetic limbs, but not for other less obvious injuries. “There is no protocol in place for psychological checkups, or referrals to ear doctors and opthalmologists,” Trujillo said.75

Survivors sometimes face new problems when they attempt to get replacements for prosthetic limbs that are worn out. Such replacements are in theory part of the medical care to which survivors are entitled by law. However, in practice survivors must get authorization for the replacements from the companies (known as Administradoras de Regimen Subsidiado, ARSs) charged with administering the government’s healthcare programs, or from state health authorities.

Guillermo Gil, who works with landmine survivors in the state of Santander, told us that in his experience “the ARS’s always deny requests for replacements, and so we always have to file legal complaints before the courts to get the replacements.”76 Guillermo estimated that in the last year he had probably had to work with six or seven different survivors to file legal complaints against healthcare administrators in the region, to get medication or replacements to which the survivors were legally entitled. They won every case, but Guillermo pointed out that the initial denial of the replacement “discourages the victim in the rehabilitation process.”77 Unless the survivors have someone to advise them on how to file the legal complaint, they might be unable to claim the benefit.

Reform proposals

Luz Piedad Herrera, who runs the Colombian Vice-Presidency’s Antipersonnel Landmine Observatory, says that with international assistance, the government is strengthening victim assistance programs. In particular, she highlighted the strengthening of the University Hospital of Valle del Cauca and the University Hospital of Santander, which would provide level 3 care to landmine survivors.78

Some of the gaps in victim assistance are being partially addressed in the National Development Plan for 2006-2010, recently approved by the Colombian Congress.79 In the plan, the Colombian government states that during this period it will carry out actions to ensure “integral and retroactive attention” to landmine survivors.80 According to Herrera, this means that government authorities will implement policies to ensure that the deadlines for claiming assistance are no longer applied to landmine victims.81

For about a year, the Colombian Ministry of Social Protection has been working on a draft decree to address victim assistance. Herrera asserted that she expects the government to have a final draft of the decree, or possibly of a law, by March 2008.82

In its latest statement on victim assistance at the April 2007 meeting of states parties to the Mine Ban Treaty, the Colombian government stated that it is developing an integral rehabilitation law to cover all disabled persons, including victims of violence, equally. It also stated that it had developed an Integral Rehabilitation Plan that the government plans to start implementing on a trial basis with the goal of eventually implementing it nationwide.83

International Assistance

Various international entities and foreign governments provide assistance to Colombia in connection with landmine issues. On victim assistance, the International Committee of the Red Cross and Colombian Red Cross, as well as various other organizations such as the Colombian Campaign to Ban Landmines (which is part of the International Campaign to Ban Landmines), Handicap International, and the Landmine Survivor Network are active in Colombia and regularly step in to fill gaps in the assistance provided by the government, though most of them are unable to cover the entire country. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), International Organization for Migration (IOM), and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) are also active on landmine issues in Colombia.

The European Union recently committed itself to providing €2.5 million to Colombian initiatives related to the implementation of the Mine Ban Treaty.84 In particular, the funding will be focused on landmine risk education and victim assistance programs to be carried out by 2009. Japan has provided assistance in the establishment of medical facilities with the capacity to treat landmine survivors. Other states that have provided assistance to Colombia and to Colombian-based NGOs on landmine-related issues, though not necessarily for civilian victim assistance, include Canada, The Netherlands, Germany, Norway, Spain, Switzerland, and the United States.85

47 Colombian Law 418 of 1997, arts. 15 and 16.

48 The law provides that assistance is calculated as 40 monthly minimum wages. Law 418 of 1997, art. 49 (providing that the amount of humanitarian assistance available is to be set in the annual budget); Presidential Agency for Social Action and International Cooperation (Acción Social), Current Chart of Percentages of Humanitarian Assistance Available According to Disability, http://www.accionsocial.gov.co/documentos/Montos.pdf (accessed June 2, 2007) (listing maximum amount as 40 monthly minimum wages). Currently the monthly minimum wage set by law is 433,700 colombian pesos. Decree No. 4580, December 27, 2006. At the current exchange rate of approximately 2,000 pesos to the US dollar, the monthly minimum wage is approximately US$217, so the total assistance would be US$8,680.

49 Colombian Law 418 of 1997, art. 16 (providing that the assistance shall be provided “as long as the request is made within the year after the event has occurred”).

50 Colombian Decree 1283 of July 23, 1996, art. 30(b).

51 Ibid, art. 32(2).

52 Ibid. The decree provides for a payment of up to 180 daily minimum wages. The daily minimum wage is approximately 14,456.6 colombian pesos, so the maximum payment is 2,602,188 colombian pesos, or approximately US$1,301.

53 Ibid, art. 32(3). The decree provides for a payment of 600 daily minimum wages, so the payment in the event of death would be 8,674,000 colombian pesos, or approximately US$4,337.

54 Ibid, art. 32(1).

55 Ibid, art. 32(5).

56 Colombian Law 418 of 1997, art. 26.

57 Ibid, art. 42.

58 Human Rights Watch interview with Javier Pallares de la Rosa, September 28, 2006.

59 Human Rights Watch interview with Mariela Trujillo, victim assistance expert at the Medellín office of the Colombian Campaign to Ban Landmines, October 4, 2006.

60 Colombian Vice-Presidency’s Antipersonnel Landmine Observatory, Chart on Frequency of events from Antipersonnel Landmines and Explosive Ordinances, 1990 to May 1, 2007, http://www.derechoshumanos.gov.co/minas/descargas/frecuenciamunicipal08.pdf (accessed May 18, 2007).

61 Ibid.

62 Ibid.

63 Landmine survivors can receive a maximum of US$8,680 in humanitarian assistance plus a US$1,301 disability payment.

64 Human Rights Watch interviews with Mauro Antonio Joaquí, October 2-3, 2006.

65 Human Rights Watch interviews with Jhon Ferney Giraldo and his mother, Consuelo Giraldo, October 4 and 6, 2006.

66 Human Rights Watch interview with Luz Piedad Herrera, September 27, 2006.

67 See Law 418 of 1997, art. 16. See also Colombian Vice-Presidency’s Antipersonnel Landmine Observatory, Assistance to Victims of Antipersonnel Mines and Unexploded Ordnances, p. 6 (Chart on Attention Route for Victims of Antipersonnel Mines and Unexploded Ordnances), http://www.derechoshumanos.gov.co/descargas/guiaatencionvictimas.PDF (accessed June 2, 2007) (listing six-month deadline for claiming disability benefits).

68 For example, of 139 cases of landmine survivors that the Colombian Campaign to Ban Landmines reviewed in 2005 and 2006, only 17 survivors had received humanitarian assistance. Seventy-nine had lost their rights to payments because the deadline to claim the benefits had expired. The victims who lost their rights to financial assistance reported that they had not claimed the benefits in time because they did not know about the deadlines. E-mail communication from Camilo Serna, Colombian Campaign to Ban Landmines, to Human Rights Watch, June 13, 2007. While this is only a partial sample, which does not include all civilian landmine survivors in Colombia, it suggests that the deadlines are a significant obstacle to survivors’ ability to access benefits.

69 Human Rights Watch interview with Luz Dary Mesa, victim assistance expert at CIREC rehabilitation center, October 1, 2006. Human Rights Watch interview with Mariela Trujillo, October 4, 2006. Decree 1283 requires that victims fill out claim forms, obtain a certification from local authorities stating that they are victims, and file original receipts for each of the medical and transportation expenses they want covered. Decree 1283, art. 36. See also Colombian Vice-Presidency’s Antipersonnel Landmine Observatory, Assistance to Victims of Antipersonnel Mines and Unexploded Ordnances, http://www.derechoshumanos.gov.co/descargas/guiaatencionvictimas.PDF (accessed June 2, 2007), pp. 8-10 (listing an assortment of documents that survivors must provide to claim each government benefit).

70 Human Rights Watch interview with Luz Dary Mesa, October 1, 2006.

71 Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. Diana Molina, head of the Physical Rehabilitation Department, San Vicente de Paul Hospital, Medellín, October 5, 2006.

72 Human Rights Watch interview with Mariela Trujillo, October 4, 2006.

73 Human Rights Watch interview with Luz Dary Mesa, October 1, 2006.

74 Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. Diana Molina, October 5, 2006.

75 Ibid.

76 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Guillermo Gil, Santander province coordinator of the Colombian Campaign to Ban Landmines, April 9, 2007.

77 Ibid.

78 Human Rights Watch interview with Luz Piedad Herrera, September 27, 2006.

79 Colombian National Development Plan 2006-2010, Chapter 2.2, Section on Antipersonnel Landmines and Unexploded Ordnances, http://www.dnp.gov.co/paginas_detalle.aspx?idp=906 (accessed June 8, 2007).

80 Ibid., p. 88.

81 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Luz Piedad Herrera, June 8, 2007.

82 Ibid.

83 Statement of the Government of Colombia on Victim Assistance and Economic Reintegration, Intersessional Meeting of States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty, April 24, 2007.

84 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Luz Piedad Herrera, June 8, 2007.

85 Ibid. See also International Campaign to Ban Landmines, Landmine Monitor Report 2006, Colombia chapter, http://www.icbl.org/lm/2006/colombia.html#fnB174 (accessed June 20, 2007).