VI. Conditions of Confinement:

Isolation and Related Issues

Isolated Confinement

International norms prohibit subjecting children to “closed or solitary confinement or any other punishment that may compromise the physical or mental health of the juvenile concerned.”533 New York state regulations permit isolated confinement, known as “room confinement” or “lock-up,” only when a child “constitutes serious and evident danger to himself or others.”534

The facilities’ monthly reports record only the relatively few instances in which room confinement is imposed because a girl poses a danger to herself or others.535 In these official records, Tryon reported no use of isolated confinement for the period between January 2004 and January 2006.536 For the same period, Lansing reported an average of 2 instances per month of room confinement for periods of less than an hour. Isolation for more than an hour occurred an average of 6 times per month, ranging between 0 and 19 times per month.537

Yet girls in both facilities described incidents of being confined to their rooms for long periods of time for seemingly arbitrarily reasons or because staff found it more convenient.538 Girls complained most of isolation in Tryon Reception Center, where all girls to be confined in an OCFS secure or non-secure facility are initially sent for two weeks for evaluation.539 Although OCFS literature states that girls “receive thorough assessments – e.g. medical, educational, psychological and mental health” in addition to formal orientation during the two week period,540 girls held at Tryon Reception Center complained that little time was spent assessing their needs or providing them with services; rather, the bulk of their time was spent sitting alone in their cells. They reported that during the day they were not allowed to lie down on their bunks.

Such isolation also occurs in the regular housing units of Tryon and Lansing. Interviews and grievance logs suggest that girls view doing chores as a privilege, because it represents an opportunity to leave their rooms.541 Girls complain that staff sometimes deny them the opportunity to do their chores, or start girls on their chores late, resulting in more time spent by the girls in their rooms.

Some girls confined at Tryon complained of confinement in Tryon’s “mudroom.” Felicia H., 17 at the time of her incarceration, described the “mudroom,” which exists in each unit at Tryon:

You come in the unit, and to the right there’s a big area with rooms off it, and to the left that’s where we live, and in the middle there’s a hallway with a booth in the middle, toward the outside. That’s the mudroom. The mudroom is a regular hallway, it’s small, when you get in trouble, they say, “Go to the mudroom, stand with your hands behind your back.” You have to stand still and look straight forward.542

Asked how long she was made to stand in the mudroom, Felicia H. replied:

Three hours or so. I was mad about everything, I was always mad. Sometimes staff is in there with you, sometimes not. If they’re confronting you, there’s staff. Or they’ll just come in and out to check on you.543

Alicia K. described her experience in the mudroom:

It’s a little hall between the two sides of the unit. There is nothing in there. You stand, you can’t sit. Sometimes a staff member is there, sometimes not. You’re there an hour or longer sometimes. The mudroom usually leads to a restraint. You have to “assume a position.” That’s stand up with your hands behind your back in the shape of a diamond. If you move, it’s an automatic restraint. They kind of egg you on, they yell at you. “If you move one inch, I’m going to drop you.”544

Another girl held at Tryon complained that a staff person had spit in her face and told her to “shut up” when she was being held in the mudroom.545 Such examples suggest that girls are made to stand alone in the mudroom as a form of punishment, although the staff members involved may view these incidents differently. As described elsewhere in this report, however, HRW/ACLU were not permitted access to the facilities nor to members of the line staff, and therefore could not obtain the staff’s perspectives or other information to test the validity of these accounts.

A subtler form of isolation takes the form of restrictions on conversation among girls. Some girls complained that although not locked in their rooms, they were kept away from their peers.546 Denise J. said that if a girl was caught talking to other girls at Tryon Reception Center, she was punished.547 Selena B., who had been held at Lansing, said that Christmas was fun in the facility because “we got to associate with each other.”548

Social isolation can be expected to be especially damaging to girls because research reveals that connection with others is essential to their development.549 In addition, when persons with any propensity to self-harm are placed in isolated confinement, they demonstrate a very high incidence of anxiety and are much more likely to harm themselves.550 The following comments of the girls themselves, drawn from facilities grievance logs in which staff members summarize girls’ complaints, suggest that isolation and prolonged lack of stimulation negatively impact girls’ mental health. One grievance cites “having to stay in their rooms all the time. It affects her because she thinks about cutting herself.”551 Another complains that, “she is staying in her room for long periods of time and she begins to think about what her stepfather did to her.”552 Current understanding of the importance of a “relationship based” model of juvenile programming is contradicted by the practices of the Lansing and Tryon facilities.

Idleness

In addition, international standards require that incarcerated juveniles be provided with beneficial activities,553 yet girls describe being subjected to lengthy periods of idleness at the facilities. Grievance log entries show complaints that girls are, for example, “sitting there and doing nothing,”554 “sitting around doing nothing-wants something to do,”555 and “tired of being bored.”556

The problem of idleness in the Lansing facility appear to be most severe in the disciplinary “C-Unit,” which was created to contain the most problematic girls. The threat of confinement in the “C-Unit” is also used to curb misbehavior by girls in other units. The girls held in the “C-Unit” have very little to do, must attend school in the unit, and are never allowed to attend assemblies or other facilities events.557

It’s very boring. The kids don’t have structured things to do for a great deal of their day. That’s why the kids go crazy, get into fights. There’s isn’t enough to do. There aren’t enough art supplies. They spend an inordinate amount of time indoors.558

Limitations on Contact with the Outside World

A number of factors converge to cut off girls incarcerated in New York State from the outside world. The remote location of the Lansing and Tryon facilities is a major factor effectively weakening or severing ties between girls and their families and communities. The sheer distance between the facilities and girls’ homes is exacerbated by restrictions on contact and further yet by staff interference with girls’ communications. Moreover, the attorneys who represent children during delinquency proceedings essentially cease to do so when children are sent to OCFS facilities, and are not even routinely informed as to which facility their client enters. The combination of these factors, along with the failure of grievance mechanisms and the absence of oversight, hide conditions within the facilities from the public eye.

Lack of Attorney Access upon Incarceration

Under international law, children are entitled to legal representation during delinquency proceedings as well as in post-adjudication proceedings, at the very least to appeal the incarceration decision itself.559 Likewise, under U.S. law, children are entitled to legal representation during delinquency proceedings, 560and professional standards require post-disposition representation to file appeals, conduct regular reviews of how the youth is faring, ensure receipt of services, and assess the continued appropriateness of placement, as well as address conditions of confinement.561

Children in New York receive little post-disposition representation. In New York State, about half of the children charged with offenses are represented by the Legal Aid Society or other institutional legal services providers and the other half are represented by state-funded, or “18-B” attorneys.562 In New York City, between 65 and 70 percent of children charged with juvenile delinquency are represented by Legal Aid.563 Factors such as the courts’ and attorneys’ overburdened caseloads and lack of resources contribute to a dilution of the quality of representation and delays in proceedings, and can make post-adjudication follow-up with youth impossible.564

Counsel is available for appeals of individual cases, but defense counsel are not funded to do follow-up representation concerning conditions of confinement once children are remanded to OCFS custody. Not surprisingly, the girls interviewed by HRW/ACLU reported not knowing who their lawyer was, having only seen their lawyer briefly in court, not being contacted by their lawyer after their case was adjudicated, and not attempting to contact their lawyer after being taken to the facility. Selena B., who was 12 years old when she was placed in OCFS custody, said, “I was supposed to appeal, I had a yellow slip to appeal, but I lost it in court.”565Even those children who maintain contact with their attorneys once incarcerated are sometimes blocked from contacting their attorneys or from communicating with them in private. One Lansing resident filed a grievance stating that she received no help calling her lawyer.566 Improved attorney contact would provide a means for incarcerated girls to communicate their concerns to the outside world, and the absence of this outlet makes it less likely that problematic facilities conditions will be addressed.

Family Visits

The geographical isolation of New York’s girls’ facilities poses an enormous barrier to girls’ exercise of their right to family contact. Although the majority of children held at the Lansing and Tryon facilities come from New York City, both facilities are located in upstate New York. The Tryon facility is about 190 miles away from New York City. The Lansing facility is about 230 miles away. These long distances severely limit incarcerated girls’ access to their families.

Often, family members do not have access to a car, or must rely on other relatives for transportation, or may have difficulty finding their way to the facilities even if they are able to find secure transport. The facilities offer no bus or other transportation services to families. In New York State, the percentage of children living in families without a car, 22 percent, is much higher than the national average of 6 percent.567 In New York City, where many of the families of incarcerated children reside, over half of households have no car available to them.568 Thus, despite the availability of weekend visiting hours, the location of the facilities and the failure of authorities to help families bridge the transportation gap denies children family visits. Janine Y. described her experience at Tryon Reception and at an upstate non-secure facility:

They lock us up so far from home. How are our parents supposed to come see us? They’re not so fortunate to be able to go all the way upstate. My family never came. It was too far. And my aunt had a little baby.569

Restrictions on visitation may also interrupt girls’ access to family. Family members may only visit on Saturdays and Sundays from 1:00pm to 4:00pm, a major barrier for family members who must work on weekends.570 According to agency regulations, children have the right to receive “any and all visitors” during visiting hours, although facilities “may” act to exclude visitors unaccompanied by the child’s parents, guardian, or “other suitable person.”571 The facilities themselves interpret these guidelines narrowly: According to facilities staff at Tryon, only relatives over the age of twenty-one who are on a list of approved visitors are allowed to visit the residents and, in practice, it sometimes takes months for residents to add visitors to the list.572 Tryon’s grievance logs contain complaints by girls that an aunt and uncle, and the father of a girl’s child, were excluded from making personal visits.573 One girl confined at Tryon complained that she was not allowed to see all of her family and “[w]ants to know who can really determine who ‘immediate family’ is. Wants to be able to see ALL of her family.”574

The distance between the facilities and New York City not only affects families’ ability to visit their children, but also impedes many outside service providers who would otherwise be available to work with girls incarcerated at Lansing and Tryon. According to a New York City service provider assisting girls exposed to commercial sexual exploitation, her group rarely makes contact with girls from Lansing or Tryon because the sheer distance to the facilities makes conducting outreach there impracticable. 575

Girls, moreover, experience geographical isolation from their families at an early and determinative phase of their incarceration. During the two week evaluation period prior to their final placement, girls are held at Tryon Reception Center, which is physically as well as administratively part of the Tryon complex. Boys, on the other hand, spend their two week evaluation period at the Pyramid Reception Center, located in the Bronx, in New York City. Thus boys’ families can more easily visit their child during a frightening and isolating period of initial incarceration. Although OCFS literature describes “[f]amily involvement” as a “key element” in the evaluation process,576 such involvement may, as a practical matter, be impossible for the families of girls.

The U.S.’s international human rights obligations recognize the right to respect for the family, a duty which continues despite a child’s incarceration.577 International standards also recognize that each child “the right to maintain contact with his or her family through correspondence and visits, save in exceptional circumstances . . . .”578 Specifically, incarcerated children have the right to “receive regular and frequent visits, in principle once a week” from family members.579 In addition, experts in girls’ development recognize the importance of promoting and sustaining family and other relationships to girls’ psychological health.580

Telephone Calls and Mail

Under international standards, children deprived of their liberty have the right to communicate in writing or by telephone regularly with persons of their choice, and have the right to receive correspondence.581 Girls held at Lansing and Tryon are allowed some access to the telephone. They are allowed to receive a certain number of calls per week, and may make one or two collect calls per week from a pay phone. Sometimes, girls are allowed to make a free call from a staff office. Calls are limited to ten minutes each, and must be made within a window of time during the day. The grievance logs of both Lansing and Tryon contain many complaints about staff interference with telephone calls in the form of denying calls,582 cutting calls short,583 and failures by staff to help girls receive calls.584 One girl reported not being able to contact her family during the two weeks she was held at Tryon Reception.585In addition, girls reported that the line is often busy when their families call,586 and that incoming calls are otherwise interfered with.587

Girls incarcerated at Tryon and Lansing are allowed to send and receive letters. To send letters, they buy stamps with money sent to them by relatives or from an account maintained by the state into which $1.25 is deposited per week for postage and commissary.588 As with telephone calls, girls have lodged many complaints about interference with their ability to communicate with the outside world by mail. Typically, girls complain that staff fail to take out outgoing mail,589 or do so only infrequently,590 withhold incoming mail,591 deny girls paper on which to write,592 and read outgoing or incoming mail.593 A girl held in room confinement was not allowed to write a letter to her mother.594 Ebony V. said:

They don’t want you to keep your relationship with your parents. They limit your calls and your mail. Your mail gets confiscated. My aunty wrote me a letter and it got confiscated, because she wrote ‘aunty’ on the envelope and not her real name.595

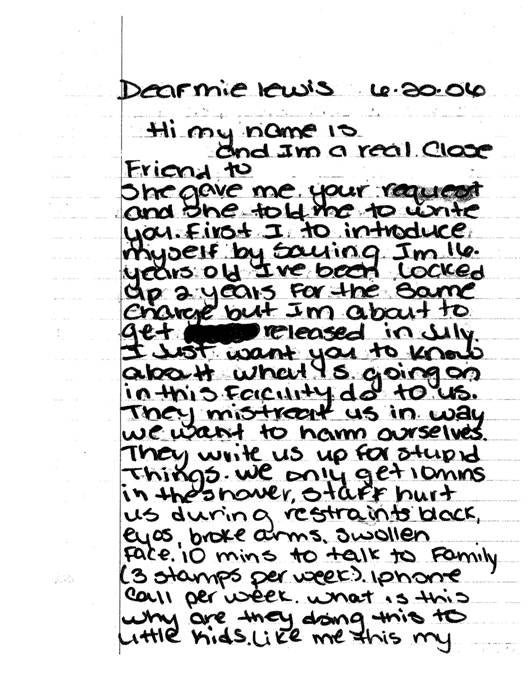

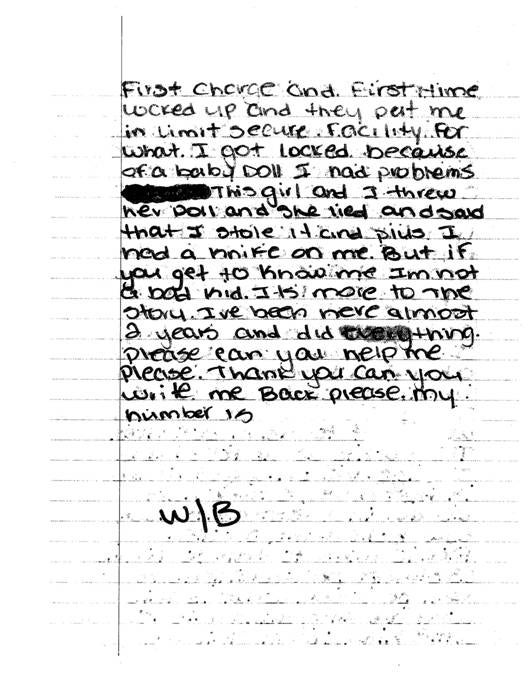

Sample letter from a girl incarcerated in the Lansing facility

Identifying information has been redacted to protect the author’s privacy.

Library and Media Access

There is a small computer lab in the library at Tryon which does not allow access to the internet. Girls held at Tryon are allowed to check one book out of the library at a time but report that the books in the library are old and do not interest them.596 A few incarcerated girls complain that they are not given enough access to books,597 or are discouraged from reading.598 Asked whether Tryon Reception Center has a library, Janine Y. replied, “No, just a book shelf with a couple of books on it.”599

International standards call for every juvenile facility to provide “access to a library that is adequately stocked with both instructional and recreational books and periodicals suitable for the juveniles, who should be encouraged and enabled to make full use of it.”600 In addition, incarcerated children have the right to access publications and broadcasts to keep themselves informed of goings on in the outside world.601

533 United Nations Guidelines for the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency (“Riyadh Guidelines”), adopted and December 14, 1990 by General Assembly Resolution 45/112, para. Rule 67. (“All disciplinary measures constituting cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment shall be strictly prohibited, including corporal punishment, placement in a dark cell, closed or solitary confinement or any other punishment that may compromise the physical or mental health of the juvenile concerned.”).

534 9 NYCRR § 168.2 (2006). A child may be confined for up to 24 hours with the approval of the facility director, and indefinitely with the approval of a high level OCFS administrator. 9 NYCRR § 168.2(f) (2006).

535 Office of Children and Family Services, Policy and Procedures Manual, “PPM 3247.15: Room Confinement,” July 8, 1997, p. 2 (defining “room confinement” to mean confinement of a child “who constitutes a serious, evident and immediate danger to him/herself or others . . .”).

536 Tryon Monthly Reports, January 2004 - January 2006. Monthly reports generated by the director of each OCFS facility and submitted to the OCFS central office were obtained by HRW/ACLU through requests made under the New York Freedom of Information Law. Two such reports from Tryon did not contain any information about the use of room confinement; the remaining reports stated that room confinement had not been used.

537 Lansing Monthly Reports, January 2004 - January 2006.

538 See, for example, Lansing Grievance #6697 (5/05)(“[name redacted] had locked her in her room. Without permission for 3 hours”), Lansing Grievance #6248 (2/05)(“[name redacted] pushed her in room, locked her in, not time to go to bed”). These and subsequent citations refer to grievance logs maintained by the facilities and obtained by HRW/ACLU through a request under the New York Freedom of Information Law. The logs contain abbreviated summaries of grievances filed by incarcerated girls. The citations herein contain the unique number assigned to each grievance and the month and year in which the grievance was submitted; Tryon Monthly Report, October 2005, p.1 (“There were an inordinate number of grievances submitted by residents. A common theme voiced is the excessive amount of time spent in residents’ rooms.”).

539 New York State Office of Children and Family Services, “Facility Programs: Brief Descriptions of Office of Children and Family Services Residential Facilities and Their Programs,” (December 2003).

540 Ibid.

541 HRW/ACLU interview with Alicia K., Syracuse, New York, February 21, 2006.

542 Human Rights Watch interview with Felicia H., New York, New York, May 4, 2006.

543 HRW/ACLU interview with Felicia H., New York, New York, May 4, 2006.

544 HRW/ACLU interview with Alicia K., Syracuse, New York, February 21, 2006.

545 Tryon Grievances #8151, #8153 (2/03).

546 See, for example, Lansing Grievance #3982 (1/03)(“staff keeping her away from peers sitting in hall”).

547 HRW/ACLU interview with Denise J., New York, New York, February 13, 2006 (“If you got caught talking to people, you got a level.”). Denise’s comment refers to the three “levels” of punishment meted out at OCFS facilities.

548 HRW/ACLU interview with Selena B., New York, New York, February 14, 2006.

549 Speech by Marty Beyer, Psychologist/Juvenile Justice and Child Welfare Consultant, in “Girls and their Unique Needs in the System,” at “Beyond These Walls: Promoting Health and Human Rights of Youth in the Justice System, April 8, 2006.

550 Email message from Terry Kupers, M.D., M.S.P., a psychiatrist specializing in prisoners’ mental health, to HRW/ACLU, June 22, 2005.

551 Tryon Grievance #8798 (8/04).

552 Tryon Grievance #8245 (5/03); see also Lansing Grievance #4195 (3/03) (“made to sit at end of hall. Drives you crazy”); Lansing Grievance #6014 (1/05).

553 United Nations Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty (“U.N. Rules”), adopted December 14,1990 by General Assembly Resolution 45/113, para. 12, (“Juveniles detained in facilities should be guaranteed the benefit of meaningful activities and programs which would serve to promote and sustain their health and self-respect, to foster their sense of responsibility and encourage those attitudes and skills that will assist them in developing their potential as members of society.”).

554 Lansing Grievance #6014 (1/05).

555 Lansing Grievance #5377 (7/04).

556 Lansing Grievance #5370 (7/04).

557 HRW/ACLU telephone interview (name withheld), June 2006.

558 Ibid.

559 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), adopted December 16, 1966, 999 U.N.T.S. 171, entered into force March 23, 1976, ratified by the United States of America on June 8, 1992, art. 14. Rights to a fair hearing includes the right to representation which is particularly relevant when the consequences are significant for the individual and in light of the vulnerability of the individual. Specifically, Convention on the Rights of the Child, (CRC) adopted November 20, 1989, G.A. Res. 44/25, U.N. Doc. A/RES/44/25, entered into force September 2, 1990, signed by the United States of America on February 16, 1995, art. 37(d) addresses the rights of children to representation.

560 In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1 (1967).

561 Seegenerally, Robert E. Shepherd, Jr., IJA-ABA Juvenile Justice Standards, Annotated (1996).

562 Under Article 18-B of the New York Family Court Act and Article 2 of the Judiciary Law, New York State delegated some of its responsibility to operate and fund a system of assigned counsel for children and indigent adults to New York City.

563 Email message from Legal Aid Society attorney to HRW/ACLU, June 27, 2006.

564 Ibid. New York County Lawyers’ Association v. State of New York and City of New York, 763 N.Y.S. 2d 397 (Feb. 5, 2003) (NYCLA brought suit on behalf of indigent children charging a lack of sufficient funding for legal representation by 18-B attorneys. The court granted injunctive and declaratory relief in form of a rate increase for state-funded attorneys.).

565 HRW/ACLU interview with Selena B., New York, New York, February 14, 2006.

566 Lansing Grievance #7071 (9/05). This and subsequent citations refer to grievance logs maintained by the facilities and obtained by HRW/ACLU through a request under the New York Freedom of Information Law. The logs contain abbreviated summaries of grievances filed by incarcerated girls. The citations herein contain the unique number assigned to each grievance and the month and year in which the grievance was submitted.

567 Annie E. Casey Foundation, “Kids Count: State-Level Data Online,” http://www.aecf.org/kidscount/sld/profile_results.jsp?r=34&d=1&c=a&p=5&x=153&y=16 (retrieved May 6, 2006)(“Kids Count Database”).

568 According to the 2000 Census, of 3,021,588 occupied housing units in New York City, 1,682,946 have no vehicle available. See http://factfinder.census.gov/ (retrieved June 27, 2006).

569 HRW/ACLU interview with Janine Y., New York, New York, May 24, 2006.

570 See, for example, Tryon Grievance #9487 (9/05)(“she is unable to visit with her mother due to her mother’s job. Wants to know if she can have special visit set up to see her mother”).

571 9 NYCRR §171-1.7 (2006).

572 Review of Legal Aid Society attorney’s redacted notes of visit to the Tryon facility on December 28, 2005 (“Legal Aid Society site visit”).

573 Tryon Grievance #9309 (7/05)(“aunt has been able to visit her for a year and a half now all of a sudden she is not allowed to”); Tryon Grievance #9281 (6/05)(“in the past, her aunt and uncle were able to visit her: now they aren’t allowed to visit-would like to see her aunt and uncle”); Tryon Grievance #9341(7/05)(“mother told her that [name redacted] baby’s father could not come to a visit unless [name redacted] mother did (per asst. dir.) would like for her baby’s father to be able to come to visits alone so she can talk to her personally”). There is also an entry which reads “Pregnant - wants to be able to have the baby's father approved to visit her," and is marked as having been denied. Tryon Grievance #9262 (6/05).

574 Tryon Grievance #9416 (9/05).

575 HRW/ACLU telephone interview with Nakiyah Hayling, case worker with Girls Education and Mentoring Service (GEMS), March 16, 2006.

576 New York State Office of Children and Family Services, “Facility Programs: Brief Descriptions of Office of Children and Family Services Residential Facilities and Their Programs,” (December 2003).

577 ICCPR, art. 17.

578 CRC, art. 37(c); see also United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice (“Beijing Rules”), adopted November 29, 1985 by General Assembly Resolution 40/33, para. 26.5 (“In the interest and well-being of the institutionalized juvenile, the parents or guardians shall have a right of access.”) See also United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (“Standard Minimum Rules”), U.N. ECOSOC Res. 663C and 2076, adopted July 31, 1957 and May 13, 1977, para. 79.

579 United Nations Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty (“U.N. Rules”), adopted December 14,1990 by General Assembly Resolution 45/113, rule 60; see also Standard Minimum Rules, para. 37.

580 Detention Conditions of Confinement through a Gender Lens, an addendum to Annie E. Casey Foundation, “Gender Lens,” Self-Inspection Instrument, p. 1.

581 U.N. Rules, rule 61.

582 See, for example, Lansing Grievance #6309 (2/05).

583 See, for example, Lansing Grievance #4043 (1/03) (“only 3 minutes to speak to her mom went over day before”).

584 See, for example, Lansing Grievance #6168 (1/05).

585 HRW/ACLU interview with Selena B., New York, New York, February 14, 2006.

586 Review of Legal Aid Society attorney’s redacted notes of visit to the Tryon facility on December 28, 2005 (“Legal Aid Society site visit”).

587 See, for example, Tryon Grievance #9031 (1/05).

588 Legal Aid Society site visit.

589 See, for example, Lansing Grievance #6072 (1/05).

590 See, for example, Tryon Grievance #9214 (5/05).

591 See, for example, Lansing Grievance #6102 (1/05); Tryon Grievance #9028 (1/05).

592 See, for example, Lansing Grievance #6066 (1/05).

593 See, for example, Lansing Grievance #7076 (9/05).

594 Lansing Grievance #5951 (12/04).

595 HRW/ACLU interview with Ebony V., New York, New York, March 16, 2006.

596 Legal Aid Society site visit.

597 Tryon Grievance #9172 (5/05)(“her unit [unit 53] needs to be provided with more books. They are getting bored.”); Lansing Grievance #5049 (2/04)(“wanted books mom sent her couldn’t get on morning call”).

598 Tryon Grievance #9375 (8/05)(staff member treated a resident "with a nasty attitude," and "acting [m]ad funny" to her for bringing a book outside”); Tryon Grievance #8860 (10/04)(“She rec’d a level from [name redacted] because she was looking at a book that was on her table.”); Tryon Grievance #8387 (9/03)(“Wants Orientation Stage people to be able to have books to read in their rooms”).

599 HRW/ACLU interview with Janine Y., New York, New York, May 24, 2006.

600 U.N. Rules, rule 41; Standard Minimum Rules, para. 40.

601 U.N. Rules, rule 62; Standard Minimum Rules, para. 39.