<<previous | index | next>>

IV. “What If”: Couples Coping with the Visa System

Wendy and Belinda’s Story (Part One)

Belinda Ryan and Wendy Daw © 2006 Private

Wendy Daw, a U.S. citizen, is thirty-seven; Belinda Ryan, from Britain, is forty. We listened to them on a sunny afternoon in their modest home in California’s East Bay. “It’s time to speak out,” Belinda kept saying. They have become activists for the unrecognized rights of couples like themselves. Wendy tells how their love, and trouble, started:

That first six months was pretty wonderful. I had just started at graduate school; Belinda had moved to this country; she was here in the Bay Area studying to be a helicopter pilot. And then she finished school. And that was when we started to realize the predicament: wow, this was serious.

She was allowed to find a job under the student visa, so she started looking for work—but it’s not that easy to find a job as a pilot. And we started to think, what will happen if she has to return to the U.K.? I had never lived with someone before. When we started living together, I felt this was a serious commitment. It crossed the line between so I want to date and so I want to spend the rest of my life with her—and what if she has to leave the country in the next week?

Belinda got her job, “just through persistence,” with a jet and helicopter charter company, and a work visa with it. “And everything was OK for a while.” Then, barely a year later, Belinda remembers,

My boss said Merry Christmas, here’s your bonus, we’re closing the company down. For us, this was a catastrophe: we’re going to have to look again at changing our whole life and leaving. But luckily I knew an aerial photographer. I told him: “I’ve got a partner here.” I wasn’t out to a lot of people, but I came out to him: my partner is a woman. He said he’d been thinking about taking someone on. … And with that I applied for a change in visa because it was a new employer.

Wendy says, “This was the fourth wrinkle in visas. About a year ago we started to add up the amount we had spent on visas. We had spent $19,000 on legal fees—the down payment on a house.”

So she got this job working in aerial photography. That was all good, except—suddenly 9/11 happens. The airspace here gets shut down for three months. She can’t fly. He was saying to her, “I’m just going to have to shut the business.”

To get away from it, we went to Britain for Christmas. And then—coming back—we went to go get on the airplane, this official is looking at passports, and he just suddenly pulled Belinda out of the line and told her she can’t get on. And told me I had to get on the plane. We didn’t understand, she had her visa, all her paperwork, she was totally legal.

It was a subcontractor who goes through passports. He actually called the U.S. embassy, talked to them, wouldn’t let us talk to them. He said she couldn’t get on the plane. And insisted I get on.

Of course we couldn’t indicate we were partners. We know if it’s acknowledged anywhere that she has a partner in this country, that could keep her out… Finally we left the airport. Belinda started calling. We got the automatic U.S. embassy helplines—this went on for four or five days, no human there picking up the phone, routed to a call center up in Scotland with no idea what to tell you. …

So I got on, tried every voice menu at the embassy, and after twenty-five selections I got a live person. I said, I am an American, I need help.

That woman helped us muddle through the whole mess. … We had to do all kinds of stuff, get something notarized—the embassy was in lockdown after 9/11, they wouldn’t even let me in the door. So the notarized form and her passport had to go in by mail, and we spent days running around London, trying to get things and get them sent.

All it was, was that our lawyer had failed to tell us that even though Belinda had her work visa papers--everything legal--still, before you come back you have to send your passport and papers to the U.S. embassy in the country you’re in so they can stamp it.

And no one at the airport would tell us, either, that this was the problem. For people who can’t speak the language like Belinda can, or didn’t have a partner: how would they find out what the problem was? We were there for an extra two weeks sorting this out. And when we get to the U.S. we can’t go through the gate together: because we don’t share citizenship, and can’t afford to be seen as a couple.

And I went really quickly, and then had to wait and wait to see if she came through…. I’ll tell you, being on the other side, and waiting and waiting for her to come through, and seeing all the others come through, and knowing that if she were turned around and sent back, there would be no way for me to find out—I had no legal right to get any information, and I knew it. None.

The incident was a crude reminder of how they lack the legal status a married couple takes for granted. Belinda says, “Even though my paperwork was good, it took me longer than two years after that before I left again. You never feel secure.”

But—the skies opened up, and we carried on, but the [aerial photography] business had taken a bashing … Last year, he says to me that he can’t afford to keep me on full time anymore. So I’ve got to make some arrangement. I thought, if he can’t keep me on all the hours of my visa, I’ve got to leave the country. …

So I am now trying to get another job. But we are in limbo. I am in depression. Financially—if I haven’t got a job by the end of next month, we have to plan our exit.97

Hard Choices

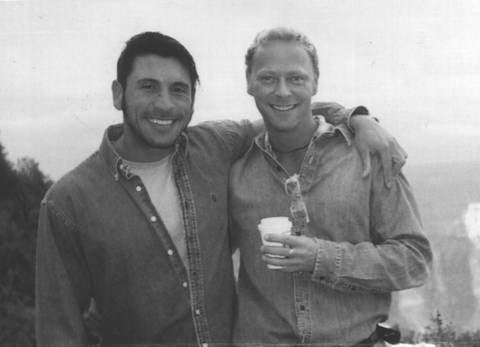

It is time to look at the stories of real people affected by U.S. immigration law. These include U.S. citizens such as Mark Himes, living in Pennsylvania with his French partner, who was in the last year of his six-year work visa. The couple had adopted a three-year-old boy, John, and was in the last stages of adopting a three-month-old girl, Claire Marie. Yet now, as visa expiration loomed, they confronted a possible huge threat to their home and stability. They wrote us, “We live year by year with no real plans for the future. We live in a don’t-ask, don’t-tell world.”98

Mark Himes holds his daughter,

Claire Marie, and son, John, while partner and co-parent Fabien

takes the picture.

© 2006 Private

They include people such as Luyen, twenty-four, a Taiwanese citizen, and his U.S. partner Aaron, thirty-five. Aaron had resettled in Taipei, far from his birth family and friends, so the two could remain together. Asked about U.S. immigration policy’s effects on them, Luyen wrote ironically, “Nothing—besides putting us where we don’t want to be and derailing our lives.”99

Lesbian and gay binational couples are forced to make painful choices. For many, consulates and immigration offices become symbols of separation. For others, they embody bureaucratic barriers, paperwork and precariousness, time spent and legal fees paid to buy a tenuous imitation of security valid only until a visa expires: happiness on a parking meter.

Among the dilemmas couples may be forced to endure are:

- Pursuing a long-distance relationship from different countries.

- So-called “visa juggling,” in which, to stay in the U.S. for as long as possible legally, the foreign-born partner switches from one non-immigrant visa to another (usually) non-immigrant visa as ability allows. For example, the foreign partner may get a tourist visa allowing a three month entry, return to her country of citizenship and re-enter the U.S. for another three months, then obtain a student visa for six months, and later try to transfer to a work visa.

- Faced with the unpalatable choice between leaving and living with the person they love in violation of U.S. immigration laws, foreign-born partners may become undocumented—staying after their visa expires.

- The U.S. partner may go into exile, leaving home for another country where they can live together legally.

All possibilities entail stress, loss, and huge expense; none promises an easy future. All these couples know, moreover, that were they heterosexual partners, U.S. immigration could quickly recognize their relationship and their right to be together. Brian and his Austrian partner Bernd, living in Colorado, struggled to find a legal way to stay together in the United States. Brian wrote us,

Life is full of challenges, and it’s too bad that this has to be one also… We live in a country full of contradictions. A country that brags about being the land of the free and yet we try to oppress so many. My partner and I are law-abiding people that simply want to live our lives together, which means we need the immigration benefit provided to married couples. We’re not asking for the whole world to change. We’re asking for something basic; we’re asking for the right to be able to love and live with the one person in the world that I want to spend the rest of my life with. That’s it.100

|

“My Country is Seriously Letting Me Down” Monica, a U.S. citizen, is thirty-one, Rebecca, from the U.K., thirty. Monica is manager and trainer for a worker-owned cooperative in California. Rebecca works in computer technology back home in Britain. They were living apart when Monica wrote us: I met Rebecca on January 31, 2003 … We professed our love for one another on day four. I asked her to marry me on day seven and two weeks after meeting one another, we registered as domestic partners at San Francisco City Hall on February 14, 2003. What more can I say? We ran head on into our destiny. … Since getting married we have been trying to find a way that we can simply be together and get on with our life. …

After searching in vain for every possible way for her and I to live together permanently here in the U.S., we have found ourselves on a dead-end road. If Rebecca had lots of money to start a business here which would create jobs for Americans, if we had money for her to be able to study here or if it were even possible in the current economy to try and find an employer to sponsor her for a working visa, we would pursue one of those options. There simply isn’t any way currently that we are able to live together permanently in the U.S.

Rebecca is not able to immigrate here and is only able to stay here as a tourist for up to three months at a time. I am able to go to the U.K. for up to six months at a time (as a tourist) but I cannot realistically do that yet because of my current professional and financial obligations.

She has not sought a job in the U.K.… because she met me and all we have been trying to do since then is simply be together. I have a lease, a car payment, a job that gives us a very modest income, and I have been taking care of my sister for the past year … Rebecca has a mortgage that needs to be paid, a car loan, as well as other financial obligations in the U.K. We are trying to subsist on my income which by no means covers all of our combined financial needs, let alone try to afford plane tickets back and forth every three months and huge telephone bills!

At any time, U.S. or British customs officers could question why we are continuing to make subsequent trips to each others’ countries. While they cannot keep us from entering the U.S. or U.K. because of our sexual orientations, they can keep us from entering if they suspect that there is something—or someone—that would keep us from wanting to go back to our own countries ... This last time, for example, she flew through New York City and was pulled into an interrogation room and questioned at length about her reasons for making another trip to the U.S. She was treated with blatant disrespect and was told that if she tried to return again she won’t be let in …

The thing that holds it all together is the fact that we are completely, totally, utterly, passionately, and madly in love. Most days we find ourselves feeling very strong and ready to take on the world. Some days we’re not so strong and find ourselves disheartened and sad that we are not allowed the same newlywed status as other people. We should still be honeymooning, but we are so busy trying to save every penny, putting together every bit of evidence of our relationship, crossing things off our never ending to-do lists, and being activists for our cause that we always find ourselves in this constant state of exhaustion and fear … We won’t allow anyone (or any government) to separate us. We have searched way too long for one another and we now know that we simply can’t live without one another.

My partner and I completely consider ourselves in every meaning of the word married. … We have made a lifelong commitment to one another and we are now one another’s reason for living. We are registered as domestic partners within the state of California, had a ceremony and have shared our happiness with our supportive partners and friends. The federal government, however, lags seriously behind on this issue of not only recognizing same-sex unions but also immigration for binational couples. We have friends (heterosexual) who met their lifelong partners in another country and were easily granted the right to marry him/her and bring them to this country to live. Men can even arrange for mail-order brides over the Internet and bring women here from other countries!

All I ask is to please open your minds and your hearts and realize that there is no difference in how gay and straight people love. The love and passion I feel for my partner is every bit as powerful and real and sacred as any straight person’s. Why is that so hard to conceive of? And whatever happened to the land of the free? My country is seriously letting me down, and either it needs to evolve or it will simply be left behind. From an e-mail from Monica (last names withheld at her request) to Immigration Equality, September 13, 2003. |

Living Long Distance

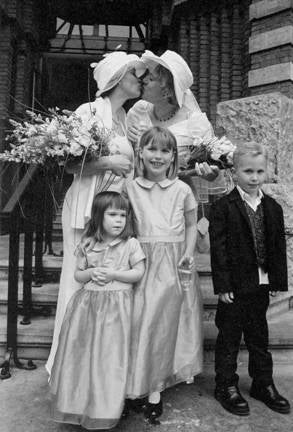

Martha and Lin McDevitt-Pugh at their wedding, May 4, 2001,

with the daughter of Martha’s best friend’s (left) and Martha’s niece and

nephew.

(Photographer: Gon Buurman) © 2006 Private

Martha McDevitt-Pugh, who left the United States in the end to be with her life partner, Lin, told us, “You don’t casually date someone across an ocean.”101 Yet many binational same-sex couples have to. Perhaps the non-U.S. partner cannot stay legally in the U.S.—or cannot even get a visa to enter it; perhaps the U.S. partner, for reasons of job or family, cannot move away. Couples hoping to build a life together are unable to create a common home. Plane tickets and phone calls become the lifelines on which a relationship survives.

Ferdinand, a Philippine citizen, met his U.S. partner Sandy over the Internet six years earlier. He was turned down by the consulate when Sandy first invited him to visit. “It was a grueling experience having to undergo an application; it felt like a medieval Spanish Inquisition.” In 2001, he managed to reach the United States as a tourist and they encountered face to face: “And it was magic!” They kept the relationship going on visitor’s visas, flying to see each other yearly. When Ferdinand wrote us, he was applying for a student visa after acceptance into a U.S. MBA program, but was still not sure this would come through. “It is extremely difficult to sustain such an arrangement, since we both are not rich. Our resources are dwindling… We are just two people who are very much in love and would like to continue that love permanently. However, we are torn asunder by rules and inhumane laws just because we are gay men. Our only crime was that we were not born of the same country.”102

Couples face enormous financial burdens trying to sustain a long-distance relationship—and again and again they stress how the present’s pressures keep them from investing in any future. Jane, who works for the postal service in Ohio, supports her Australian partner, Laura—who cannot hold down an ordinary job at home and at the same time travel to the U.S. so that they can be together. Jane, meanwhile, cannot move to Australia because her teenage child from a previous relationship lives near her. Laura, she says,

is only able to stay three months at a time. So every three months we go through the pain of her returning to Australia for another six weeks, or until whenever I can come up with the money for her to return. The emotional strain on us is only slightly overshadowed by the financial strain. Having to come up with $6,000 a year just for her traveling doesn’t leave a lot of breathing room to pay our bills, and no room to plan for the future. … If laws were inclusive to our situation, there would be a security that we are lacking now. She would be able to work. We could save for our future together. It would make all the difference.103

Harry is a teacher in Florida; Jai works as a waiter in Indonesia. Harry says, “We have been in this relationship for six years and have been able to live together only two and a half years of that time”—immediately after they met, while Jai was in the U.S. in school. “Even through the separation and loneliness we maintain our monogamous relationship… It has made our life miserable. Now money that would have been spent on making a home together is being spent on travel to be able to see him and be with him.”104

|

“Do You Think We Don’t See Through This?” Gordon Stewart is a U.S. citizen. We interviewed him alone in New York; his partner of five years can no longer enter the United States and so remains in Brazil. He met Marcelo (not his real name) when vacationing in Rio de Janeiro in 2000—”I thought it was very auspicious that it was the first day of the new century … So we had a long-distance relationship for several months.” Then they began to discuss Marcelo coming to the United States. He was a lawyer, well-qualified, but he didn’t really speak English… I sponsored him financially, though, and he got a student visa and came in January 2001 to study English for one year. He was still doing that on September 11. I somehow figured that would change the whole scene. It did, but in delayed fashion.

In January 2002, he was accepted in St. Francis College in Brooklyn, taking law and business classes—preparing for law school in the U.S. But his student visa needed to be renewed. In May 2002, he went home to do that. I was afraid the new immigration situation might cause some problem, but he was issued a new F visa to pursue his studies.

So Marcelo completed his third semester at St. Francis, and returned to Brazil in May 2003 to renew his visa again. In June, Marcelo went to the U.S. consulate in Sao Paolo. He had all the paperwork—and suddenly the American visa officer began asking questions about his sponsor and why he was coming to the U.S. “Who is this sponsor? How did you meet him? Is he married? Are you married? Do you think we don’t see through this?” His visa was rejected.

Gordon personally contacted the ambassador at the U.S. embassy to Brazil:

The officer who rejected him writes me in a proud email: “This guy in his mid-twenties”—Marcelo was thirty-nine—”says he wants to study in the U.S. at some unknown university.” He said this was not a bona fide student visa application: he has other reasons to be there. And he said, “What you need is a good immigration lawyer: good luck.” It was evident that they absolutely did not read the application: “This guy says he wants to go study in the U.S.”: he already had been there studying! You just want to scream at these people.

I responded, “I respectfully disagree,” gave the chronology, said it was an appropriate course of study for what he was trying to do. He wrote back—tell the applicant to reapply; he will have another visa officer, good luck

They were rejecting him because he had “immigrant intent,” though they hadn’t said it yet. Marcelo asked a former colleague to write a letter saying that he maintained professional ties in Brazil. Marcelo and the ambassador thought that was pretty good. I was skeptical.

Marcelo goes in for a new interview. The officer, a woman, calls a man over to look at the application. He says, “This is not legitimate. Cancel the visa.” It’s obvious in retrospect that they rejected him on the basis of his appearance and the “oddity” of being sponsored by an “older single man.”

Through a lawyer, we found out that the guy who rejected him first was the head visa officer; obviously the reapplication was a fraud, setup, façade—on which he had to spend $300 in application fees.

We engaged a lawyer, wrote the consul general—he rejected it immediately: they said, we are not looking at this case further. The ambassador herself wrote to me and said, these people report to Homeland Security, not to me: there is nothing I can do.

For the first month, I couldn’t sleep at all. We had bought an apartment here. We were thinking, this was our life—we would be together. All his stuff is in it. He went home for three weeks and he has never been able to come back. It’s crazy. I haven’t spent more than one weekend in the apartment since. I can’t stand being there. It’s just the fact of not being together, of having dreamed of being together.

Since then, I call Marcelo every day, and it’s a hassle and you have to find the calling cards and Marcelo spends a fair amount of money on calling cards too. If I didn’t have resources, the relationship never would have worked out—it would be too expensive, difficult and costly, emotionally and financially.

And since then I have gone to Brazil every other weekend, basically. We’re extremely lucky that I have the resources to go back and forth. That puts me in the top one-percent category as far as suffering is concerned—and even at that it’s not been easy. There’s personal strain: we can spend the weekend together but that means I have a ten-hour flight on Friday night and a ten-hour flight on Sunday night and the flight arrives at 6 a.m. Monday morning and I have to be at work by 8. And we’re on different schedules, wavelengths, I’m always jet-lagged when we meet, and it’s so difficult to connect. I get to Brazil on a Saturday morning and he may have things he wants to do and sometimes all I want to do is sleep. And there’s the strain of trying to maintain my friends and family contacts in the U.S. because I am always going to Brazil. I cannot lead a normal personal life because I am spending so much time in airplanes to sustain my relationship. He is waiting for something to happen that will solve the problem and there is nothing he can do. We both suffer the strain.

My company has agreed to transfer me to the U.K. and he will go there. But, he still has nightmares about the rejection—they did it in such a public way, forty people in the room and the consul yelling at him, “Do you think we don’t see through this?” He was totally humiliated.

The inequality is obvious. I felt I had always been privileged for my entire life, and always tried to understand other people’s circumstances from without—and when this happened it just clearly showed me what prejudice, bias, injustice is: because it’s totally, completely unfair.

And I feel ashamed that he comes from a country that is supposedly a “developing,” often belittled country, and yet they have gone forward and supported gay people and human rights in so many different ways. It’s embarrassing. I haven’t focused a lot on being angry, because I have to keep my energy focused on keeping the relationship together—on travel, on literally staying awake. The last thing I want to do is to get on a crammed plane, economy class, for ten hours to go to Brazil tomorrow. But I’m glad I can do it. I would go every weekend if I could. If this isn’t a commitment to a relationship I don’t know what is a commitment to a relationship. And the fact that they don’t recognize or respect that kind of commitment, is just beyond me.

From a Human Rights Watch/Immigration Equality interview with Gordon Stewart, New York, November 23, 2004. |

Juggling Visas

Struggling to stay together legally in the U.S., many foreign partners in same-sex relationships juggle visa options—tourist, student, or work. Their lives become an alphabet soup, with maintaining or moving to B, F, or H status an almost daily, draining obsession.

Lynnette, a special education teacher in California, tells a typical story. She fell in love with Mei-ling, from Taiwan, a printmaker and painter, who now works as an art instructor for the disabled. It is particularly difficult to adjust non-immigrant visas to immigrant status:

She has had a practical training visa, then an H1B visa (both non-immigrant visas) and is now filing for a change in status to get a green card. It took four lawyers and constant negotiation with her employer to get to this point. It has made our stay together stressful, unsettling (how can you settle down if you don’t know where you can live or stay?) and expensive. It has been demoralizing to see how little our relationship means legally. We mean so much to each other but nothing to my government, even though we are contributing members of society.105

People using student or training visas to stay with their partner often find themselves forcibly infantilized—regressing to seek a redundant education. The costs of staying in school can be acute, since most student visas allow limited opportunity to work; the U.S. partner must frequently furnish tuition and support. Moreover, foreign students usually cannot get financial aid, and even at state institutions pay several times what in-state residents do—an inequity remediable if their relationships were acknowledged to permit them residency.

Gillian and her partner Sariya, from Thailand, met while the latter was studying in the U.S.: “We fell in love and have been together ever since. That was almost five years ago.” Living on a student visa has been difficult, though, “adding stress and uncertainty; making it necessary for Sariya to stay in school without a break at a cost to her stress level and our finances.”106 Rebecca, twenty-seven, wrote us about her three-year relationship with her U.K. partner, Eileen. Each summer, Eileen comes to the U.S. on a training visa to serve in a summer camp, and Rebecca works there to be with her.

We have both essentially put our professional lives on hold to be together. … It is difficult to explain to loved ones that I am going back to work at camp for one more year—when they (and I) know that I could get a full-time year-round job elsewhere that would allow me to start saving for retirement and a house. As it is now, we basically scrape to get by.107

To make ends meet, some are forced to violate the terms of their visas by working. The job is almost always poorly paid. Tony, a social worker from Brooklyn, met his Brazilian partner while Miguel was visiting New York. “We were forced to maintain a long-distance relationship for three years until Miguel could get a student visa,” Tony says:

He was a public defender in Brazil; when he got here with his visa, which precludes work, he was only able to take the occasional house-cleaning job. Oh, wait, did I say he was a lawyer in Brazil and had to work as a house cleaner in New York City? … His choosing to come here on a student visa has plummeted him into a regressed role as student. Had he been my spouse he could have looked for work. If Hillary Clinton had to clean toilet bowls that might jolt her esteem too. As for me, it has been stressful at times bearing a large financial burden… We constantly have to sit with “what if.”108

|

“I Can Buy a House Here … But I Just Can’t Live My Life in It” Will and Stefano have been committed partners for a decade and a half. Will is a US citizen; Stefano has dual Australian-Italian nationality, born of Italian parents who had recently migrated down under when he was born. The couple fell in love while Will was working in Sydney on a business visa. “We met at a dance party with fifteen thousand people there, gay and lesbian Mardi Gras. We danced till 6 a.m., exchanged phone numbers using the eyeliner of a drag queen at the coat check, and have been together ever since.” They live in the United States now, where Will works for a large corporation, and have adopted a child. But, they have had a perpetual struggle to keep Stefano in status so that Will can keep his job here, and they can stay together. For five years Stefano has been taking college courses, working to complete a B.A. in fashion and merchandising. Will says: “What is most annoying is instead of his being able to work and contribute his talents to this country, he has to spend his time in school and we are actually having to pay for him to be here.” Stefano elaborates:

In order to be with Will, I haven’t been able to work since 1996. And I pay more at the state university as an international student. We owned a home in state, and I was a state resident, but at school I was an international student. Any state resident who was a U.S. citizen would pay $1,500 a semester; we were paying close to $10,000 a semester for me to attend school.

It’s so strange. I can buy a house here—they are fine when I pay taxes. But I just can’t live my life in it. Stefano is faced with his student visa expiring and decisions loom. Will formally adopted their son Evan, from China, fourteen months old when we talked to them, in 2003: We found an adoption agency that we knew was not openly discriminatory towards gays and lesbians. They cared only about improving the life of an orphaned child. I submitted my application as a single, unmarried male. Now we are going through the process of second-parent adoption for Stefano. Our lawyer already told us this will affect Stefano’s status: by adopting an American citizen, he will be making clear his intention to stay. So our son, who seals our commitment to each other, might seal our separation. Stefano may never get a visa again. But they have already burnt their bridges—by crossing one: publicly declaring their relationship by celebrating their marriage, across a river in Canada, in 2003. “We were married in Niagara Falls, Ontario. Our wedding invitations and wedding bands say, ‘Head over falls in love.’” Now they have begun the process of emigrating to Canada. Will says, “Having a child made us realize that we need to find a home that will be home, a place where we can be for fifteen years and be secure.” Stefano corrects him: “I knew even before we had a child that I definitely wanted to leave. I don’t like it here any more.” Will adds, I no longer feel committed to this country. We want to be in a country whose values align more closely with the values of our family, so that as we raise our son, he doesn’t question why his parents are out of status, unusual, discriminated against. “It’s only recently I broached with my mother the concept of being Canadian,” Will says. I think this whole experience has opened up her eyes. She’s always been a very proud American, proud of what this country stood for; my brother fought in the first Gulf War; and every time we talk with her she tries to defend America, it’s not so bad, and I think it’s only recently she’s beginning to say, this sucks. Three very important people in my life are most likely now going to be leaving this country because of this. All of our friends and family echo that. Shameful that this is supposed to be one of the most progressive countries, founded on the concept of democracy, and here is this one essential fact: we are in love and we can’t live here. While we interviewed the couple, Evan played quietly in the background, and three dogs roamed the room—beautiful Australian beagles which, Will explained, were thirteen years old: “We’ve had them since our first year together in Sydney, and they have followed us ever since.”

When we came together to the U.S. to live, we brought them with us; they got a vet test that entitled them to travel with us, and were put in a crate on the same flight. When we landed in the U.S., we waited by the baggage carousel and they brought up our crates, and then a wildlife inspector trundled by—a middle-aged woman, sort of small and crotchety. She bent over, looked into the cage, and said, “Aren’t they cute!” And that’s all it took: that’s how they got into the country. So it is easier to get my dog permanent residency than my partner of fourteen years. From a Human Rights Watch/Immigration Equality interview with Will and Stefano (names changed at their request), New York City, January 19, 2005. |

Those in the U.S. on work visas face different, equally difficult challenges. There is the constant fear that if the visa-holder loses the job, he or she will be forced to return home—meaning separation or dislocation for the couple.

As discussed above, finding an employer willing to sponsor a foreigner can be hard. The hirer must expend vastly more effort than taking on an U.S. citizen entails. The authorities have near-absolute leeway to reject work visa applications; requests can languish in endless delay. From Connecticut, Rich related how his Polish partner Greg, studying business, tried to get a work visa for a job in his family’s U.S. firm. The then INS turned him down, Rich reports,

saying the business was too small to need a college-educated person in the management role they were offering. Since his family owns several other businesses, we appealed, explaining the business was larger than the application would lead one to believe… In February of 2003 Greg’s case suddenly got transferred to the INS in Washington. … Greg spoke with the INS weeks ago and they informed him it can take a year from the date the case moved to Washington for his appeal to be answered. So, we are left in limbo. If his work visa is not approved, we would be separated and I would be powerless to help. I don’t even want to think about it! My family would be devastated if I had to move out of the U.S. This entire situation is just horrid.109

Both partners’ careers may suffer in trying to stay together. When Maggie wrote us, she had left her North Carolina home to live in Australia with her lover Sarah. Both were computer programmers who met while Sarah was in the United States, and had struggled to remain there: “We researched our options, but the most promising ways to allow her to stay would have required her to take up careers she had absolutely no interest in (nursing, for instance) or attempt to go to college in the U.S. and somehow pay for that. That’s no way to live your life, spending your days playing at something you have no interest in just to be with the one you love.”110

Stopped at the Gate: Harassment by Immigration Authorities

Whether traveling to meet, or trying to keep the foreign partner legally in the U.S., couples fear the power of U.S. immigration officers to break up their lives by stopping them at the border. Crossing customs is a constant reminder of how fragile their relationships are, absent legal recognition.

Stephanie and Callie on a visit to Callie’s hometown in Oregon. © 2006 Private

Stephanie and Callie have been partners since 2003. Stephanie is a U.K. citizen, Callie from the U.S. For the first year, they exchanged visits, managing to spend months together at a time—but always knowing the days were limited. Stephanie says, “The airport is just the worst thing …. You always worry that you’re looking too shifty when you’re going through. You constantly worry you’ll be turned away, although you’re doing nothing.”111 Callie adds:

We were always careful if we were traveling together not to carry any documents that showed us as a couple together, in any way. No letters, cards, photos even… We didn’t want to get caught—no, not “caught,” because we weren’t doing anything illegal. We never considered breaking the law, because we both wanted to do it completely legally.112

Other couples, however intent on legality, have worse

stories to tell. Thomas, twenty-eight, lives in Chicago, an ocean and half a

continent away from his French partner of eight years, Francois. They met

while Thomas was studying in Paris as a college junior, were able to live

together in France when Thomas returned there for graduate school, but then had

to separate when he got a teaching job at home. “That was two and a half years

ago, and we still have not found a way to bring Francois to the U.S. to live.” They visit and vacation together; Thomas remembers how, returning to the U.S. from a joint trip to Canada,

I had to go through separately because we’re not considered a family, and I stood on the other side while one official was giving Francois a really hard time, asking probing questions that were not even relevant. Francois was not at liberty to say that my boyfriend did a really nice thing and bought me a present [this surprise trip to Canada] – he was worried that this would incur even worse treatment. The immigration official demanded proof that he would return to France, but Francois didn’t have his plane ticket on him, so the official wasn’t even going to allow him back into the U.S. Technically—we weren’t aware of this—he has to carry it with him always to prove his intent to leave. I was standing at a distance watching, feeling powerless. The immigration official saw me and said that I couldn’t even stand there—and berated him. I had to move away till I wasn’t visible; it revealed that we were a couple. He treated him differently—smirking, laughing, treating him with disgust. After all this, he just said, Take your papers and leave, and he let him through. It was all about his own power.

Then I think, this man represents my country— is this a country that I want to be associated with? Do I want to bring Francois to the U.S. if this is how he is going to be treated? This is where I want to live because it’s where my family is, but does this place represent the values that we have?113

Gitte Bossi-Andresen, a Danish citizen, was detained twice while entering the U.S. to visit her American partner of almost eighteen years, Kelly. “They asked me why I was going to school, what I was doing there, if I could prove it, why I had left the states, why I was coming back… I was bombarded with questions.” Near tears, she says:

As a kid, I was always told, you are a diplomat for your country, you’re a diplomat for your family, so when you go out, you behave in that way. So being detained, treated and singled as a criminal, it really means something to me. Maybe those incidents don’t have to do with directly with me being gay, but they do indirectly: had I not been gay, I would have been married.114

The passport record of visits that keep a relationship going can turn incriminating at immigration control. Nathalie Fuz remembers how once JFK immigration “held me for an hour, asking why I was going back and forth so much, grilling me about the multiple entries. … I always get nervous when I enter the country. They are not pleasant.” Her U.S. partner, Kelly, says, “It’s always nerve-wracking.” When they cross the northern border for a trip, “There’s this Peace Bridge between Canada and the U.S., and now ironically we feel this whole anxiety about crossing the Peace Bridge to come back. We can’t eliminate the factor that our relationship isn’t valid. You feel totally suspect.”115

|

Deported

Many couples fear immigration officers, but Asa and Tony have a particularly horrible story. Asa, a British citizen, was deported while trying to visit Tony in the U.S., and Homeland Security launched its own investigation of their relationship. Tony, forty and a denizen of Atlanta, Georgia, met Asa, thirty-three, during a vacation in Britain in early 2002. They fell in love, and, like many other couples, immediately faced a quandary: how to be together? At the time, U.K. immigration laws gave residency to unmarried foreign partners of British citizens—but only after the couple had lived together for two years. The two therefore planned eventually to move to London, but since Tony had commitments to his own business in the U.S., they would need to demonstrate their cohabitation through Asa spending as much time as possible with him there. “I went to the INS,” Asa says, “and they told me there was no limit to how often I could come in and out of the U.S. legally, as long as I don’t overstay. So I would go in and out of the county every ninety days.” I spent the majority of my time during those two years in the U.S…While I was forced to quit my job in Britain to spend time in the States, I could not work, drive, own a cell phone or even a bank account in America—all the things most people take for granted. My partner was powerless to do anything to help. … One of our major hurdles was that I had to live in America [to prove to the U.K. that they had cohabited for two years], but I couldn’t do so legally in the U.S.’s eyes. Yet, we had to build documentation that we were living together. We had to walk this fine line. Still, Asa left every three months and remained legal. In 2004, having met the requirements, they resettled in London, where Tony got a new job. In June 2005, Tony had to return to the U.S. for an eight-week business trip—”which was a long time to be apart,” Asa says. “We said I’d go there on holiday for two weeks [at the end of Tony’s trip], and fly back together. Tony asked me if I was worried about coming into the country. Ironically, every other time I was horrified coming into the country, the most nerve-wracking experience. This time, I wasn’t worried at all.” At the Atlanta airport, “I got to immigration. They asked me the standard series of questions: last time I was here, what I was here for—a holiday. I kept the answers as simple as possible. They put my passport in an orange folder, so I knew. They took me into another room.”

That was the horrible experience in itself… There was an African woman who had a little baby and they were letting the baby into the country and not the mother. And then they had a few other people who’d been put aside for questioning as well. At least I spoke English—I could tell the translators weren’t doing a proper job interpreting.

They asked details about me. I told them the hundred percent truth. I said I’m in a same- sex relationship, we live in the U.K., we transferred our lives there … It was blatantly obvious to me that the questioning was homophobic. It’s hard to explain… You knew they could do it because our relationship had no status, and the end result was that it all happened to me because I was in a same-sex relationship … I guess I just wasn’t human.

He asked me questions about our landlord when we had lived in San Francisco. Were they already investigating us? He told me that he didn’t think I’d be let into the country. I said, “Don’t do this to me.”

They never said, You have been refused entry because. And I never actually asked, why aren’t you letting me in. I just said, please, don’t do this to me. I was given a refusal, and made to sign. The flights to the U.K. were all booked. They didn’t think they could permit me to fly back to another E.U. country. They found a London flight leaving in a couple of hours, with one seat in first class—for $5,000. I bought that. When my flight came up, I got escorted there by a Homeland Security officer and boarded onto the plane. “The American government has singled gay people out for mistreatment,” Asa says. “We have been careful to abide by every law and hurdle placed in front of us, and we are still being treated as criminals.” Tony waited hours for Asa to emerge—then waited for him to call when he got back to London that night. He remembers,

At 10 or 11 a.m. next morning, someone was banging on my door—two officers standing there, cars sitting in front of my house. I was shocked. But I knew what it was. Homeland Security.

[The agents] didn’t want any pleasant communications. They informed me of my rights—I could have an attorney present; they recorded everything. I told them all they asked for. They wanted to know what my relationship to Asa was. I knew he’d already told them, so I told them the same.

They knew things about our relationship. We had moved to San Francisco for about a year. We’d signed a lease there, so we had both our names on it. Sitting in my house, they had the documentation: they asked about our landlords in San Francisco by name; “Did Asa live with you for the year?” I explained that no, he’d been doing it legally, leaving and entering every ninety days. They didn’t believe me. They asked, “Where are you living now?” I said in London. Obviously, they didn’t believe I was living anywhere but Atlanta, because I still own the house there. The line of questioning was: when did we meet; how long in was he in the U.S.; did I know that it was a violation of law if I let him live with me and if I harbored an illegal immigrant? They asked me how Asa supported himself in the U.S. They knew he didn’t have a job in the U.K. “So he lives there but you pay all the bills?” By coincidence or not, Tony says, “One or two weeks later, I got an internal revenue audit. That’s still going on… I’m not at risk, but—I suspect that they’re making sure that I didn’t pay Asa.” “We never did anything that should have flagged us,” Tony says. “Honestly, I love my country; if we could live in America tomorrow, I would want to come home. …Our home is there. My family is there. Asa’s family is spread out. He and I are here alone in London.” And yet, Tony says, “they treat me so well over here, almost to the point that it freaks you out. It’s the other side of the spectrum. You don’t see any hate here. It’s really nice.” From a Human Rights Watch/Immigration Equality telephone interview with Asa and Tony (last names withheld at their request), January 5, 2006, and an e-mail from Asa to Human Rights Watch, January 5, 2006. |

Seeking Safety and “Looking Gay”: The Asylum System

Some foreign partners know that, because of their sexuality, at home they would face violence, arrest, or death. Yet in claiming asylum, they do not always find a full or sympathetic hearing.

In one well-known case, Jorge Soto Vega, from Tuxpan, Mexico, had suffered violence in his community and even family since childhood. Police severely beat him, threatening to kill him unless he left—because, they said, they wanted to cleanse the town of gay people.

In 2002 in the U.S., Soto Vega claimed asylum. Immigration judge John Taylor found credible evidence that he was persecuted in Mexico because of his sexual orientation—yet threw out his claim. Soto Vega, he said, looked straight and could hide his sexual orientation if he chose. Taylor wrote: “It seems to me that if he returned to Mexico in some other community, that it would not be obvious that he would be homosexual unless he made that ... obvious himself.”116

Both the confidence in stereotypes, and the belief that the closet can guarantee both sanity and safety, remain rife in the immigration system. Tom Smeraldo lives in New Jersey with his Venezuelan partner of four years, Emilio Ojeda. In 2002, Emilio first learned that it was possible to claim asylum from sexual-orientation-based persecution. At his hearing in late 2003, Tom says, “The officer asked offensive questions—clearly she was not trained; for instance, ‘when did you start acting gay?’” Emilio says,

Anyone investigating asylum for sexual orientation should know better than to ask the questions she did. The implication was, you are faking that you are gay. … Immigration is looking for the stereotypes; for instance, a judge said to a friend of mine who was making a claim, “You don’t look like a lesbian.” They assume that all immigrants are straight and all asylum-seekers on the basis of sexual orientation are frauds or criminals.

Tom Smeraldo and Emilio Ojeda in 2006 in their home. © 2006 Private

Emilio appealed a deportation order. On October 11, 2005, the case was postponed for six more months. Before that, Tom told us that “I don’t know how long we can live like this. If Emilio loses, we’ll apply immediately for Canadian immigration. I would love to be treated equally somewhere, and I don’t want to die living my life as a second class citizen.”117

Giovanni was beginning to work for LGBT rights in his provincial city in Colombia when he met his partner Mark, a U.S. citizen, in 2001. Mark encouraged him to be more vocal. Giovanni says he and a few colleagues sent a letter to the guerilla group FARC, urging them to stop violence against homosexuals. Death threats followed; after a public meeting, a group of men attacked, clubbed, and whipped him, leaving him unconscious and with permanent injuries.

Mark helped him get a training visa to the U.S., and Giovanni relocated in 2003. They began preparing an asylum claim—a costly, time-consuming process. Giovanni was admitted to Bellevue Hospital’s program for torture survivors; doctors documented his injuries from the beating. Yet at his interview, he stared at a “stern face”:

I knew that it was going to turn out badly. When I said the word “homosexual” his face grew hard. He never looked at me. I had read about Soto Vega and so I tried to look more “gay.” I’d shaved my mustache and tried to fit the stereotypes. … At the end I said, “I’m talking, sir, with my heart, I’m telling you the truth.” I said, “Please help me, I’m gay, my life is hell in that country.”118

The written Notice of Intent to Deny refusing his claim, which Giovanni received weeks later, contained troubling phrases: “the teacher told you that he knew you were a faggot”; “you were warned that [you] would be killed because [you] were a faggot.”119 Both Giovanni and Mark were disturbed to find the word “faggot” used without quotation marks in an official U.S. government document.

Giovanni appealed. Eventually, a perhaps-embarrassed INS overturned the decision. However, he reflects resentfully on how abject the experience left him.

I got tortured, went to an embassy three times, I got a visa, I came to this country with my horrible English. I arrived and lived with my boyfriend. I applied for asylum, I waited for a long time with no response, I was denied and then approved. One woman from Colombia finds a man and marries him and in one year she is an American resident. Do you think that is fair?

Mark agrees: “I’m not asking for special rights. I’m just asking to be equal.”120

Lives Not in Order: The Undocumented

Undocumented immigrants are the main focus of current attempts to reform—or radically restrict—immigration. But what does it actually mean to be undocumented? It describes a foreign national who is not in the U.S. on a valid visa. There are several ways of becoming undocumented.

First, a person may cross a U.S. border without an entry visa. “Entrance without inspection” happens mainly along the Canadian and Mexican borders. It has become the popular image of “illegal” immigrants, but this actually is much less common than other ways of becoming undocumented. More usually, one enters on a valid visa such as a student or work visa, and overstays its term. A student, for instance, would begin to “accrue unlawful presence” when she no longer attends a university but remains in the United States. 121

An undocumented immigrant who accumulates from 180 days to a year of unlawful presence is barred for three years from returning to the United States. An undocumented immigrant who accrues unlawful presence of more than a year is subject to a ten-year bar. Ways exist to overcome the bars to returning, including (in some cases) marrying a U.S. citizen, but—again—this is not available to lesbian and gay families.

Lesbians and gays arguably have fewer possibilities than most other immigrants to obtain legal presence here. Moreover, it may also be difficult for the U.S. partner to move abroad. More formidable obstacles than work and family ties may intervene. Foreign laws may not acknowledge their partnership. The U.S. partner may not have the education or background to be accepted permanently in a country where immigration law and policy favor skills over family ties.

Thus, many find themselves boxed into the difficult decision to stay together in the U.S. where the foreign partner is “unlawful.” No one wants this. Undocumented foreign partners told us they had actively tried to keep in regular status but could find no alternatives that would preserve the relationship. Fearing they might be forced into it, Stephanie and Callie told us that “Overstaying your visa is not like killing someone; it’s just staying to be with the one you love. Yet you’re treated as a criminal.”122 For most, going undocumented means a life of privation, immobility, and fear.

|

“A Constant, Gnawing Fear”

Tara, a U.S. citizen, twenty-four, and Stacy, her Canadian partner, twenty-five, lived in small-town Appalachia when they wrote us, and had been together for three years. Stacy is undocumented. They stayed together in the U.S. because Tara, studying and working in market research, was in a far better position to support them than Stacy would be in Canada. Tara says, “There are no steps available for us to live together here legally. She does not have a college degree, Canada is not in the green card lottery, and she has no relations in the U.S. You would think our northern neighbors would have an easy time getting into the U.S. for good, but that is not the case.” I can’t begin to describe it. We suffer financially because she must work at a horrible job that has already once ruined her health. Because of the “dirt” her employers have on her legal status here, she has to take whatever hours they give her, which vary from too many humanly possible to barely double digits a week. She could easily have a job where I work that would pay much better and be easier on her body, but can’t due to her legal status here. Not having to stay on her feet all day and carry heavy loads would do wonders for her health.

It’s almost impossible for us to visit her family … Every time we cross the border, we know we risk her not being allowed back in the country. Her aunt died almost a year ago. She did not get to see her one last time for fear that the post-9/11 border would not let her return. She took this pretty hard, as did I.

There is a constant, gnawing fear any time we see any official of the law. Whenever someone knocks on the door unexpectedly, we both jump, panicked, wondering if it’s INS or other government officials, finally catching up with us… It’s very hard knowing someone can rip you away from the one you love at any time.

We don’t participate in many public activities together for fear of being turned in. … Almost a year ago, Stacy sustained a serious back injury. We went to hospitals in the US, but considering she has no health insurance here, not much was done. The condition worsened to a point that we made an emergency trip to her hometown in Canada to see a doctor that would actually look at her injury and take it seriously. As a result, she had surgery, almost a month of inpatient therapy, and still has a permanent limp because of this condition, which could have been averted had she been given proper medical care from the outset. We dropped to barely one income since I was going to school full time and working hardly any hours at my job, and because of her uncertain legal status she was in no way eligible for any aid whatsoever. Imagine being taken off work for six months with no income, not even workers’ comp or unemployment.

I am still trying to pay off debt from this period of our lives. This isn’t a story begging for your pity, merely an example of how a binational couple must live. We have no rights, we know we can be forced into separation at any moment (I imagine there are stiff penalties for one such as myself who helps an illegal live in the U.S. for so long), all because we had the good fortune to be two women who love each other more than anything.

If we are ever caught and forced to separate, I don’t know what I’d do. She is my life, my love, everything I’ve ever wanted in a woman… She gave up everything, and I do mean everything, to live here with me. When she came over the border she had a backpack of clothing and nothing else. Everything we have together now we built up together. It’s not her clothing and my clothing, separated, it’s our clothing, our computer, our television, our dog. … Oddly enough, we hardly ever fight, especially about money or our situation. We just love each other, and couldn’t imagine not being together.

We’re normal, nice people who don’t do much out of the ordinary. It strikes both us and our friends as humorous, in a twisted way, that we’ve broken so many federal laws over something as silly as us being allowed to live together. From an e-mail to Immigration Equality from Tara and Stacy (names changed at their request), October 20, 2003 |

The undocumented are trapped here, usually unable to leave the U.S. without facing legal bars to their return. Stephen told us of his European partner, who had been in the country since 1995: “It has put a lot of stress on our relationship with fears that immigration will show up and deport him. There is also the stress that he has not seen his family in seven years, whom he is extremely close with. He (we) missed the marriage of his sister and the birth of two nephews from two of his brothers. There is also the fact that his parents are elderly and if one died he would not be able to leave the country for the funeral, for fear of not being allowed back in. We are a committed couple in every sense of the word. We recently celebrated eight years together.”123

Chet, sixty-seven, and his Taiwanese partner Wei, fifty-nine, had been committed partners for two decades, during most of which Wei had lived in the U.S. undocumented: “We have lived together and been devoted to each other for the last twenty years and have tried every way possible to get him permanent residence… Every possibility has been a dead end because of immigration laws against gay partners.” In that time, Wei had been able to visit Taiwan only twice to see his ailing mother; confusion about the order of his names in his passport meant that his overstay was not in the records, and allowed him to return. “His mother passed away two years ago but he could not chance returning for the funeral for fear he would not get another visa.” Now Chet fears that if he dies, Wei could be deported if he comes forward as an heir. “We live day to day praying that the immigration laws will change and we can live together in peace without the constant fear that something will happen that will cause his deportation.”124

Detention, and deportation after it, indeed menace the undocumented. Immigration detention has ballooned in the U.S. since September 11. (Whereas in 1995, 33,000 people were deported and some 5,500 were held by immigration authorities on an average day, in 2003, more than 77,000 were deported and 20,000 detained on an average day.125) Human Rights Watch has repeatedly drawn attention to unacceptable conditions in detention centers—many of which are local jails, or contracted centers run by private corrections companies. 126 Standards for immigration detention centers exist, but are inadequately and irregularly implemented.127 Immigration Equality’s work with lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender immigrants has shown patterns of harassment, discrimination, and abuse in detention. HIV-positive detainees also face discriminatory treatment, including denial of medications and placement in twenty-three-hour lockdown if they self-identify—clearly discouraging them from coming forward and seeking treatment.

The non-recognition of lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender people’s relationships can also weigh against foreign partners facing removal proceedings. Eligibility for bond (that is, release from immigration detention) for people who have received a removal order, and applications for cancellation of removal, can, in some cases, be influenced by whether the person has a family member—spouse, parent, or child—who is a U.S. citizen or permanent resident. This is particularly so if the deportation would cause the family member “exceptional and extremely unusual hardship.” DOMA codified that same-sex partners cannot qualify as family members for these purposes.128

To stem the fears that come with being undocumented, some couples contemplate a sham opposite-sex marriage for the foreign partner. The idea of entering into a fraudulent partnership only because the government will not recognize their real one infuriates and humiliates many. Amy, living with her British partner in San Francisco, feared they would have to separate when a student visa expired:

Now I think if we want to stay in California, an arranged marriage is the only option we can afford. If we’re found out, the non-U.S. citizen is kicked out of the U.S. forever and the U.S. husband can be put in jail or fined. But, as a gay person, I don’t want to live a lie. The idea of having to be at my girlfriend’s wedding is just a day I don’t know how I would get through.129

Wade Nichols and Francis Shen in 2002 on

their honeymoon. © 2006 Private

Wade Nichols and his Taiwanese partner Francis Shen, living together in what for Wade is exile in Taipei, had considered a fake marriage to stay together in the U.S. Francis has been harassed by U.S. immigration before. He says marrying is “a long shot, and then I’d have to go through immigration again, but that time it would be more difficult because I’d be lying. It was hard enough when I wasn’t lying. … It’s insane,” he adds. “The government would rather have people lie to them than be honest with them.”130

|

“And Then It Was All Taken From Me”

Wayne Brown, forty-seven, a clinical social worker, lives in Florida at the moment. His partner Ricardo Espíndola is from Argentina and is unemployed. Wayne, a Canadian citizen, had been a lawful permanent U.S. resident for many years, working as program director of a large HIV/AIDS service group. Ricardo came to the United States in 2000 on a three-month visa waiver available to Argentineans. He found work; he stayed; he met Wayne. The two had launched the paperwork to have their partnership recognized for immigration purposes in Canada, and planned eventually to move there and be fully legal. Things took a wrong turn in late 2004 on a desert highway. Ricardo’s undocumented status came back to haunt him—and the couple was ripped apart. “We traveled through the U.S. in the course of our years living together,” Wayne said. “This was just one other trip that we had planned. On September 21, we flew into Albuquerque, and we left early the next day to drive to southern New Mexico.” We were out in the desert. We saw a barrier—we thought it was the park entrance we were headed to. Ricardo was driving. He rolled up to the gate. Then we realized they were border patrol. We just froze. We were in shock. We didn’t expect a random stop. If I had known that border patrol could stop anyone within 100 miles of the border, I wouldn’t have had us go there. Ricardo says, It’s like the last moment before you die. It all happens, and you just can’t believe it. A guy poked his head in and asked, are you American citizens? I think if we had said yes, he would have let us through. It was kind of random and casual. I answered that I was from Argentina. Wayne says, I’m dying in my seat. I was totally petrified. We’re surrounded by all these military guys in broad daylight. Ricardo was so courageous. I wouldn’t have done that myself. He took my hand. He said, “Could you please have some compassion. This is my family. You could choose not to do this.” The border patrol officer was completely taken aback. Ricardo remembers, “Then the guy said to me, what if I wanted to come to your country? Would you let me come there?” The men made Ricardo step out. Wayne had to stay in the car, but could hear their voices: “You’re a very muscular guy; you’re not going to try anything, are you?” Ricardo notes, “They treat you like that all the time. Like you’re about to burst, like you’re an animal. You’re not supposed to move unless you’re told. “ Once inside [the detention facility], I just collapsed and started crying. They kept asking me questions. A guy there was very nasty. “You’re going to try to resist us. You’re going to get what you deserve. Are you on steroids? We should arrest the other guy”—Wayne—”as well.” Wayne says: As soon as they took him, I called my attorney. An officer came out and said to me they might be arresting me, too, for transporting an illegal alien. I said that he’s not an illegal alien, he’s my partner. He left and then returned. “I need to ask you, do you guys have AIDS?” I said, “No, sir, I’m not HIV-positive. I’m on a work visa serving the HIV community.” Then he said, “Do you understand why I’m asking that question?” I didn’t know where he was going with that.

Ricardo was held in immigration detention for forty-five days. At first, they would lock me in different cells alone. Another person who was arrested for deportation at the same time, a woman, could have her boyfriend with her, but me they kept me without Wayne, alone in a cell. They had me in a very, very cold cell for around ten hours. Finally, in the evening they took me to the detention center in El Paso.

In El Paso … they fed us some nasty food. They took away my clothes and gave me prison clothes. There’s no record of them doing that, because whenever they took a photo of me in detention, they did so with me in my civilian clothes.

The first night we didn’t sleep because we were on the floor with a bright light overhead. When I got to the barracks, I slept almost for ten days. I only got up for food. People had to wake me to eat. They refused to give me vegetarian food, so I exchanged food with others. The guards would notice and try to take the food away… I didn’t tell anyone that I was gay when I was in detention. You’re afraid of everything. … It felt like death.

An immense darkness. At first, I could not sleep or eat. I would wake up with nightmares, I would choke my screams, I would start crying; it was terrifying. All I could do was call Wayne on the phone. Those calls in a way would keep me alive but on the other side of the phone was Wayne, just as desperate. I went through the money I came there with so quickly because I needed a lifeline. I was in misery.

This country that I love so much was punishing me in such a terrible way. That was a feeling that I couldn’t share with anyone there. They were all trying to get to the U.S., but I had a life, I was already there, and then it was all taken from me. Wayne tells his story: I was delirious. Back in Albuquerque, I had to change my flight. The woman at the airport didn’t even need to ask; she could tell from my face…

It was forty-five days of hell. I didn’t sleep. I was manic for about three weeks. They wouldn’t tell us anything. My attorney was sending letters to the El Paso Detention Office. We kept offering to expedite a voluntary deportation. They declined. No explanation. It was like my insides were ripped. For the first three weeks when I was back in the apartment, a part of my mind would hear him or think he was just in the next room…

In early November we found out that he would be deported in the next ten days. I hoped to see him at his layover in Miami, but even that didn’t work out. Ricardo was sent back to Buenos Aires. With Ricardo in Argentina, their application for partnership status in Canada had to be relaunched. Fifteen months later, it is still pending. (They cannot marry under Canadian law until both are actually on Canadian soil.) Still living on different continents, they hope that soon Ricardo will become a Canadian permanent resident and they can eventually reunite. “I can’t describe how terrible” this period has been, Wayne told us. For six months I wasn’t able to do my job. I was dealing with people with very similar issues to what I was going through. A large percent of our clients are undocumented. There wasn’t a day that I wasn’t breaking down and at my wits’ end.

So, about six months ago, I had to resign and take a less stressful job that pays much less. I’ve moved from a two-bedroom apartment to a studio. The room I live in now is just piles of papers and documents. The money we spent in the last year on phone calls! We have no savings now. We’re living literally paycheck to paycheck. But Ricardo adds, “In Canada, I’ll have my family together again. We had a beautiful life, and then all of a sudden, they cut your arms off. You’re powerless. Everything changed overnight.”

From a Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Ricardo Espíndola and Wayne Browne, December 9, 2005. |

Gender Identity, Marriage, and Immigration

On April 16, 2004, William Yates, Associate Director for Operations of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS, the former INS), issued a memo on “Adjudication of Petitions and Applications Filed by or on Behalf of, or Document Requests by, Transsexual Individuals.” The memo stated:

CIS personnel shall not recognize the marriage, or intended marriage, between two individuals where one or both of the parties claims to be a transsexual, regardless of whether each individual has undergone sex reassignment surgery, or is in the process of doing so.

Yates’ stated rationale was “to ensure consistency with the legislative intent reflected in the DOMA.” However, in many U.S. states, as in many foreign countries, transgender people whose identity papers had been changed from their birth gender could still contract perfectly legal marriages—and had been able to do so for years. Since there is no federal family law, the U.S. has always looked to the law of the state or country where the marriage was entered into to determine its validity. The memo changed the rule, codifying that these marriages were suddenly void for immigration purposes.131

The memo claimed this had been an INS practice for some years. Yet one female-to-male (FTM) transgender man, Chris, wrote us that the INS “did approve these marriages if valid where performed, still in existence, and not solely entered into for immigration purposes. … It is one thing if you never had the right to sponsor your foreign partner for immigration purposes (same-sex couples); it’s another thing if you had the right, and all of a sudden a new memo comes and thus legally married couples are shattered to hear from the officers that their marriage is no longer acceptable for immigration purposes!” His own story was one of rejection:

Me and my [foreign-born] wife have been partners for eighteen years. We got married in July 2001. When I applied for adjustment of status in the fall of 2001 based on our legal marriage, the interviewing officer and his supervisor told us they will retain our application and decide if they will forward it to their marriage fraud unit or to their continuing unit—the “black hole.” We were totally shocked since we didn’t do anything fraudulent… Since then we’re fighting. Our attorney requested more information. Finally, after almost a year, we got a note. But rather than giving us details about their mysterious claim, the note said that my application had been denied and that we have fifteen (!!) days to appeal their decision. We appealed it: that was the beginning of 2004. 132

A year later, Chris and his wife still had received no word.

I know more couples whose lives are shattered due to this new policy… Except for Massachusetts there is no place in the U.S. that does allow same-sex marriage, while lots of places/states do allow transsexuals to legally get married. But would the government care, or apply logic?—no. … As you can see it’s not “homosexuals” or “activist judges” or the “ACLU” who are trying to redefine marriages. It’s our own government who already redefined legal marriages where one spouse is a transsexual. The impact of such policy is horrendous.133

In fact, less than six months after the memo, on September 21, 2004, the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) reversed it in a case decision. Noting that several states had allowed transgender people to marry even before DOMA was passed, while the House Conference Report on DOMA had stated that “no state has ever permitted homosexual couples to marry,” it concluded those marriages were not among the ones the bill intended to invalidate.134

Yet prejudice and discrimination still confront transgender people in immigration—and elsewhere. Crucially, not all transgender people can legally change identity, or marry. Some states do not acknowledge change of identity; in 1999, a Texas court nullified the seven-year marriage of a transsexual woman to her husband, saying that a person’s legal sex is fixed at birth.135 States that allow identity change have varying—or simply unclear—rules on what medical or other procedures permit it. The result is a crazy-quilt of local definitions and revocable rights that leaves transgender people’s personhood in the U.S. federalized, fragmented, and patchwork.

|

“These are Scary Times” Amber is a male-to-female transgender woman from the Bahamas, twenty-eight years old. While living in the U.S., she had sex reassignment surgery. She changed her name and driver’s license legally. She was dating a man who was a U.S. citizen, but they had not yet decided to marry. In 2003, however, facing a deportation order, she was taken into immigration detention. Her experience showed an inflexible system unable to accommodate, or even comprehend, non-conforming gender identity and expression.

When I was at Varick Street [Immigration Detention Center] they asked me tons of questions, and they strip-searched me. They gave me two male guards even though I asked for a female guard. They responded: “Yeah, you can ask for anything but you’re not going to get it. Don’t worry; we’re not seeing anything new.”

They’re rude to you, and then they walk away and make the comments. “Yeah, he looks like a bitch, but he’s a dude.” Relaying jokes, about trans women they had seen–”I saw a beautiful woman but then she sounds like Barry White.” Then, all the young officers come to your cell to take a look… The only person I was allowed to call was an attorney, and he didn’t answer. You can only make local calls, so I couldn’t call family or friends in New Jersey…

Afterward they took us to Passaic County Jail in Paterson, New Jersey, and put us in a big holding pen, and I’m sitting in a room full of men. I was nervous because I’m realizing that most of these guys are convicts. You just go into survival mode; you’re polite to all and you don’t know how they’re going to respond.

The head officer went ballistic when he saw me. “What is a female doing in here?” The officers said: “She looks female but she’s not.” They take you for a medical exam. You surrender your clothes and then they give you new facility clothes. I was placed in an all-male housing unit that held over eighty men; some were even sleeping on the floor.

The Jamaicans there were singing a homophobic song to me—Boom bye bye in the battyman’s head. Goodbye to the gay man because we’re going to shoot you in the head. Some said, “Leave the child alone.” Others said, “I could just kill him.” You hear these threats. I was there for a week-and-a-half to two weeks. … Over the course of being there, things changed a little bit… During the day, you think they want to kill you, and at night, they slip you notes telling you how much they like you.

This housing area was like a cage, an old-time zoo… At night, other cells would call me, they knew a girl was there, all day and all night —”Hey Amber, I love you, are those real titties”—you walk by and they’re screaming at you, catcalling, or threats – “See you on the street and I’ll kill you.” … I had asked to be put alone or in protective custody. But an officer told me that would be worse – 24-hour lockdown. Those people are not allowed to move, can’t get services as readily, like law library or visits. It meant giving up too much. I was warned that if I asked for therapy for what I was going through as a trans person, they would put me in Psychiatric Watch, lights on 24 hours a day and your clothes taken away from you – anything you can hang yourself with –the jail was already freezing, all you’re wearing is a little vest that covers your chest and genitals…

All this time, I had not spoken with a lawyer or judge or anyone. I had money in my account, but they never let me access it. Now, I was moved to Bergen County Jail. They processed me with the wrong name—not my former [masculine] name, a name that was completely wrong. They told me to speak with an ombudsman about the name issue. When I protested they said, “Do you want a bed tonight or do you want to sleep on the floor?” I’d started the process at 11 a.m. and now it was 3 a.m. I told them, “Fine, I’ll be OK.”

They put me in a dorm with room cells. You bunk with one person. I was bunked with a guy who did not care for me. There were tons of empty cells; I asked if I could one to myself. Next thing, I was taken to medical, examined by a nurse. I explained my situation. I was still on a low dose of estrogen and a testosterone blocker when I was at the Passaic Jail. They said, “We don’t have your medical files, so we’ll see on Monday.”

Instead of giving me my own cell, they moved me to solitary confinement, lock-down for 23 hours a day. 75-80% of the people there are informants and sexual offenders who are at risk in the general population jail… They never let me come out for a break until late when everyone else has gone away. The phones were available from 8 a.m. until 10 p.m. They let me out after the phones shut down – midnight, 1 a.m., so I couldn’t call anyone, the ombudsman, the warden, a lawyer. They said I was a security risk, and they were short-staffed, so they couldn’t let me go to the law library, and so on.

Immigration officers don’t come to solitary because that’s not where immigration cases are. They never sorted out my name. They wouldn’t send out my mail or give me mail if I used the name Amber—because they said there was no such person in this facility. My family were coming to the facility or calling the facility, and they’d be told there was no one by that name here. Finally immigration officers came and spoke to me. It wasn’t until February that I finally saw an officer. He told me, “These are scary times, what with terrorism, we need to know who we’re letting into the country. When things don’t add up”—me transitioning— “that’s a problem.”