VI. Violence and Excessive Use of Force

It was war. I can remember it vividly because my tears haven’t dried yet….The police came with their shields and were screaming ‘Attack! Attack!’

—Rini Rumasilan, a fifty-five-year-old small trader147

Excessive Use of Force Against Residents

Evictions typically take place in highly charged circumstances. Clashes between a community’s residents and the police and public order officials during forced evictions are common. Residents and observers explained to Human Rights Watch that they felt compelled to resist the efforts to evict them and that there was often physical resistance to police, public order officials, and the irregular thugs. This resistance would take the form of brandishing sharpened sticks, throwing rocks, physically blocking access to their homes, and setting tires on fire. The Deputy Chief of Jakarta’s public order officials, Jornal Effendi Siahaan, also alleged that residents have used knives in defense of their homes.148 Human Rights Watch found no evidence or allegations that any residents had resorted to or had possession of firearms. The police and public order officials who come to enforce the evictions carry firearms, knives, or baton sticks, and have access to tear gas and water-cannons. Police and public order officials also wear protective helmets with faceguards and protective padding, and have riot shields for protection.

Given the limited threat which the residents’ resistance offers and the equipment and numbers available to the police and public order officials, it is striking how consistently residents reported excessive force by the police in responding to unrest or potential unrest. The resort to force is compounded by the fact that it is largely due to the failings of the Jakarta administration—such as its failure to consult with residents, negotiate in good faith, and provide adequate compensation to those who are uprooted—that evictions take place in highly charged circumstances.

Agus Adil recounted for us the mayhem of the eviction of his community in Pondok Kopi, East Jakarta:

A group of us formed to negotiate with the public order officers so that we could get a little time to collect our things. But the response was that they wanted to do the eviction then and there….The public order officials didn’t want to negotiate and there was fighting. Many people were injured….At least one person was shot but I think there were more. There were also people beaten until they were bleeding. We were throwing stones at the public order officials. After we failed, we all fled and straight away they started destroying the houses.149

Fellow community member, Pramana Prihatin, shared his experiences:

It started at 10 a.m.…[The public order officials, police, and military] arrived and we formed a sort of resistance. They let off tear gas and then shot bullets, some real bullets and some [“non-lethal”]150 bullets. As soon as we heard the gunshots we ran. We were scared we would be killed. It was the police who were shooting. I was resisting and fighting, but as soon as we heard the gunshots we retreated. I saw that it was the police who drew their guns. They were not shooting into the air; they were shooting at the [members of the] community who were resisting them. Maybe five or seven shots, so we ran to the back, and we were chased by the security forces, the police, and public order officials. There were possibly a thousand of them, there were several of us who were injured.151

Human Rights Watch interviewed a number of other people beaten by public order officials during the same Pondok Kopi eviction. One woman we spoke with, Kalarensi Aries, was badly beaten when she tried to intervene in the arrest and beating of her younger brother:

I saw that my younger brother was arrested by some public order officials…so I went to talk to them to ask them not to beat my younger brother. When I went to protect my brother, I was also hit. I was beaten on my head until it was bleeding. I had to have seven stitches. I don’t know who hit me, it was very crowded, and there were many public order officials. I was just trying to protect my brother. The public order officials were carrying wooden [baton] sticks….Some were hitting me with their sticks, and some with their hands and fists. I can’t tell how many were hitting me. Many. They hit me on my head. What I felt the most was on my head, and on my left side, but I was also hit in other parts….My younger brother was also wounded. Some police arrived and one of them said, “Don’t kill him,” and then they took him to the police station. I came home and [then] went straight to get some medicine from the health clinic. At the clinic they stitched my head, but I was still feeling sick, so I went to the [alternative health practitioner]. One of my ribs was broken, on my left side….I went to the [alternative health practitioner] for one month before my broken rib was healed.152

Kalarensi’s brother had to receive stitches above his right eye and on his head, and also lost one of his teeth.153

Pramana Prihatin, quoted above, was also beaten:

I got a cut on my head. I was beaten on the head with a wooden stick [baton/truncheon]. It was about fifty times, in my head, on my body, on my back also…I went to the hospital for the cut on my head. I had to have stitches in my head….At the time of the beating I was standing outside my house trying to resist. I was standing outside my room, and about one hundred public order officials came toward my house….My friend and I were trying to [close] a fence so that the entrance was shut off. The public order officials arrived and pulled us apart…Then I was beaten…I don’t know exactly who hit me. I was straight away hit in the head, and I fell. There was some dirty oil nearby, and they poured the oil over me. It was about five public order officials who did it. Then I ran off. They chased me but they couldn’t catch me, because my skin was very slippery from the oil….The community health center gave me five stitches.154

The government forces appeared to resort to firearms in an offensive, rather than a defensive, manner during the eviction at a site in Cengkareng Timur. Fifty-three year old Rini Rumasilan told us what she saw that day:

There were five hundred households at the time, but the forces sent to evict was ten thousand. It was [all the different divisions of] public order officials, and [gangs of thugs]. I myself can’t say exactly how many, because there were so many people….The police came with their shields….I was panicking because suddenly there was a siren, suddenly all the electricity was out, which is why we couldn’t save many of our things, and people got shot because we weren’t really prepared to be evicted. Yes, I saw it with my own eyes. There were two people shot, and we couldn’t count how many got hit by [“non-lethal”] bullets. First, they attacked with the water-cannon, and then they released tear gas. Then the community backed off, and that’s when the forces started to enter the location. They started shooting and beating people up. One person died…I was there, because the local population made a human barrier, singing folk songs and trying to negotiate with the public order officials….When they used the water-cannon, people tried to fight back using sharpened bamboo, then they were pushed back, and the forces shot at the people…[They used] a long black weapon….When we were still struggling, they shot in the air. But after the barricade gave way, then they were shooting at the people….It was like a war. Afterward we were all looking around asking: “Where is my husband? Where are my children?” It was just like a war. I feel like crying just remembering now.155

Human Rights Watch interviewed a number of people displaced by an eviction from a site on Cakung Cilnicing Road in East Jakarta in September 2005. Hariadi Tadji explained what he experienced:

I was in my house when the forces arrived. It was about 10a.m. It was the public order officers. They were wearing blue uniforms. They arrived and started destroying the house next to me. I panicked and started gathering my things together. They were very rude. They were not looking for any compromise, they just started destroying things straight away. There were about one hundred public order officials and police. Some of them were using iron sticks…[I saw some] community people try to burn some tires to stop the public order officials. They had already poured the petrol over some tires, and were about to light it, when the police arrived—five of them, but they were wearing civilian clothes—and they took out their pistols and the community ran away. [These five police] were wearing civilian clothes, but I knew they were police because they had pistols….They hadn’t drawn their pistols fully, they were just beginning to when the people ran away. I was about five meters away at the time.156

Kersen Saptono, another former resident of the site on Cakung Cilincing Road, offered this account of the same eviction:

On the day of the eviction, one of my friends and I were hit by some public order officials. It was by many of them. I was standing in front of my house trying to stop them destroying it, and I was kicked in the legs and punched in my stomach and face, and then carried and thrown out of the site. I reported this violence to the police but I have had no response, and they didn’t make a [preliminary investigation report].157

Herman Haryani described the conflict broke out during an eviction at another site, Jembatan Besi, in West Jakarta:

[There were] around seven hundred police, and around four hundred public order officials, plus or minus. But I’m pretty certain there were five hundred thugs….The thugs brought bamboo sticks and wood sticks. The public order officials had wooden batons. The police had batons and a teargas launcher….When they arrived, we threw stones at them. We were defeated, and then we had to step back, and then they started launching the tear gas….We confronted the forces with sharpened bamboos, and then the police say “Why don’t we do this peacefully? Why don’t we talk about this?” Then the people backed off, and that’s when they shot the tear gas….I saw them launch the tear gas, I don’t know names, but I know it was the police. I don’t know the exact number of tear gas canisters but it was a lot. They launched them into the location in even proportions. They had surrounded us, and they shot inwards.158

Fifty-one-year-old Lusiana Angga, told us about what happened to her son during the eviction: “Another one of my sons was shot in the buttocks. I think it was a [“non-lethal”] bullet. It hit his behind while he was running.”159

On occasion, police and public order officials destroy structures with complete disregard to the safety risks caused to residents. Ani Fatah, a forty-three-year-old woman who tried to protect a group of children during the eviction at Cengkareng Timur told us: “I collected the children and put them in the church. I put them in the church, and then the police came and burned the top of the church, so I pulled out the children and ran.”160 Wawan Muliadi, who is seventeen years old, related a similarly close call during another eviction: “I was asleep, and when [the public order officials] arrived I started gathering up our things, so they wouldn’t be burned….The public order officials just destroyed the houses. Straight away burned them. They threw oil on the house and then set it alight. I was inside the house, they’d already poured oil on the house and set it alight, and then I came out.”161

Human Rights Watch asked the Deputy Chief of Jakarta’s public order officials, Jornal Effendi Siahaan, to respond to these allegations of excessive use of force. He told Human Rights Watch: “Usually, it is that we are attacked first. People spit on us, attack us. Because of the provocateurs and the land speculators. It’s law enforcement. We have to enforce the law and clear the land.”162 The Deputy Chief also rolled up his sleeve to show a seven-inch scar on his left forearm he says was caused by a knife wielded by a resident during an eviction.163

Under international standards, the government must ensure that prior to carrying out any evictions, all feasible alternatives are explored in consultation with the affected community, with a view to avoiding, or at least minimizing, the need to use force.164 The Jakarta administration claims that it does pursue alternatives prior to evictions. The Deputy Chief of the public order officials told Human Rights Watch: “What you see in the media, it only concerns the last stage, the law enforcement forcing people to move. Usually we take preemptive precautions, negotiation, offering compensation in the form of money or another program of transmigration—helping them to move to places outside Java island, or help to go back to their original region.”165 The repeated occurrence of excessive use of force during evictions, and the failure to negotiate and offer compensation as detailed elsewhere in this report, indicates that the government is in fact failing to take sufficient preemptive precautions to avoid clashes.

Destruction and Loss of Personal Property

My house, I built that with my own sweat, using things that I had collected…And now I’m old and I don’t have a home. And my cutlery and my furniture are my things, not the government’s! How dare they take these things and throw them in the river? Most of my furniture they burned.

—Rini Rumasilan, a fifty-three-year-old small trader166

Public order officials wielding baton sticks, lighting fires, or directing bulldozers also destroy or steal residents’ personal property, including furniture, household appliances, and clothing. This arbitrary destruction and confiscation of residents’ personal belongings violates Indonesian law, and is completely punitive as it serves no legitimate government purpose.167 In the aftermath of evictions, residents also face the problem of losing their possessions to scavengers who descend on eviction sites to collect anything with resale value. We were told that police and public order officials sometimes fail to protect residents from these scavengers, even when the officials are still at an eviction site.

| Eviction: Pondok Kopi, East Jakarta

The community at Kampung Rawadas, Pondok Kopi, in East Jakarta was established in 1986 on an area of swampland that the initial groups of residents filled in and reclaimed.168 In 2001, the community contacted the National Land Agency to contest claims being made by a local government agency in charge of graveyards which asserted that it had rights over the land.169 Nonetheless, on the morning of October 29, 2001, before the National Land Agency could rule on the various competing claims of ownership on the land, some 400 public order officials, 300 police, one hundred thugs, and a handful of military forces and representatives from local government all arrived at the village.170 According to witnesses, the security forces entered the village using teargas, firearms, and batons sticks.171 Using ropes and bulldozers, the government forces destroyed approximately 400 houses, home to around 1,600 people.172 Twenty-one residents were injured.173 Evicted residents were given the option of finding their own alternative location to live and receiving construction materials from the government, or moving to land provided by the government outside of Jakarta, for which they would have to pay Rp. 1.3 million (US$127)174 in advance payments, and Rp. 170,000 (US$17) per month in rent.175 Much of the community, however, simply remained on the land. As there has been no subsequent use of the land by the government, the community has rebuilt their village in the exact same place, calling into question the legitimacy and purpose of the original eviction. As Agus Adil, a member of the community told Human Rights Watch: “Until now, the land hasn’t been used for anything else, so for what reason were we evicted? I’m wondering why the government is making the community here suffer? If [the land was used by the government] then we would feel less upset, but until now there is nobody using the land.”176 |

Sri Suharti, who was evicted from her home in early 2005, told Human Rights Watch about how she lost not only all of her personal belongings but also the goods that she sells in the shop next to her house: “My house and my shop were totally gone. Everything, all of my belongings, were all gone. All that was left were the clothes on my body. I came back, it was empty, everything was gone.”177

Kersen Saptono told Human Rights Watch that he was only able to remove some of his belongings: “It’s only the things that we had the opportunity to move out of the houses that were saved. Everything else we lost: our fridge, our TV, our wardrobe. We also lost some money. There was no opportunity to do anything. We were panicking.”178

Jullieta Indriyanti’s belongings were all destroyed by fire during an eviction carried out just days before she met with Human Rights Watch: “All of my things were burned. Some of my things had been secured by friends, but everything else has been burned. Everything was burned, all my clothes, all my cooking stuff, only the clothes I was wearing were saved.”179

A community visited by Human Rights Watch that lives under a railway flyover bridge in Cikini, Central Jakarta, complained that when the public order officials came to evict them, they came with trucks which they used to carry off the community’s belongings.180 Arti Sudewo, told us how “[the public order officials] were taking the triplex [wood board] that was good. They put it in their truck, and they left the bad.”181

Photo 4: A sign posted by a member of the community at Pisangan Timur warns “Scavengers Enter and DIE!!!” (c) 2006 Bede Sheppard/Human Rights Watch

Budi Santoso, a tailor in his forties, told Human Rights Watch that his community had to contend with scavengers stealing from them during the confusion and destruction of the eviction and its aftermath: “There were other people who came who were reclaiming the wood and metal. People were scavenging through the debris and stealing things.”182 When Human Rights Watch attended an eviction at Pisangan Timur while it was still in progress, we observed that despite the presence of hundreds of public order officials and police, it was the residents themselves who were taking precautions against theft by posting warning signs and threatening people trying to steal other people’s belongings.183 (Photo 4 above shows a sign posted by the community to deter scavengers.)

Government Use of Urban Gangs

We have this motto: “For those who don’t behave well, let’s give them a thrashing!”

—Fajri Husen, member of Forum Betawi Rempung (Betawi Brotherhood Forum) gang184

One of the military men asked me: ‘Have the thugs arrived yet?’ I was thinking that the military were there to protect us. Then a short time afterwards, two buses arrived and two jeeps, about two hundred thugs. The gang of thugs arrived and shook hands with the police and the military. I was right there. I saw it. After a while the police and the military left. Then the thugs came straight to us, into the housing complex. There was no one there to help us. I was feeling scared, I don’t know what kind of country this is with the police and the military just allowing this to happen.

—Eddie Hariyanti, a forty-eight-year-old unemployed man185

In at least seven of the fourteen incidents investigated by Human Rights Watch, gangs of thugs (preman) assisted the government authorities in the physical process of carrying out the eviction and destruction of communities. These thugs threatened residents, destroyed homes and personal property, and sometimes stole valuable belongings. These gangs routinely carried sticks, long knives, iron poles, sticks with balls on the end, and occasionally guns. As the testimony from Eddie Hariyanti above indicates, the government security forces sometimes accepted and welcomed the presence of these groups during the evictions. Human Rights Watch was told of incidents where the thugs would arrive at an eviction site around the same time as the government forces, that the thugs talked with the government forces, that the thugs carried out the physical aspect of an eviction either alongside the government forces or while the government forces were watching, and one incident where the eviction notice was first delivered by a gang and then official forces turned up to carry out the eviction. Human Rights Watch also received reports of such gangs intimidating residents prior to some evictions.

The use of untrained and unaccountable civilian groups to carry out government policies puts civilians at considerable extra risk of violence and violations of their rights. International legal standards require the government to ensure that legislative and other measures are adequate to prevent and punish forced evictions carried out by private persons without appropriate safeguards.186 Moreover, all persons carrying out evictions must be properly identified.187 Under international law, the Indonesian government remains responsible for the actions of these gangs of thugs when the government has delegated what is essentially a function of the state—carrying out evictions—to these private actors. This responsibility remains even when these gangs break the law while carrying out the eviction, through the destruction of property or violence against residents.

Herman Haryani talked to Human Rights Watch about the day of his eviction from Jembatan Besi and illustrated for us the coordinated nature of these thugs: “I’m pretty certain there were five hundred thugs….The thugs wore ribbons. Yellow ribbons. They wore them [on their wrists and upper arms]. Besides the ribbons, they wore just regular clothing. They brought bamboo sticks and wood sticks.188

An organized gang was involved in an eviction in Pondok Kopi, East Jakarta. As Pramana Prihatin recalled:

There were also gangs of thugs involved….Every time one of the houses was destroyed, they erected their flag on the site. The flags symbolized jihad, and they named themselves some kind of Islamic military group. They were acting with the police [but] were wearing civilian clothing. I saw it myself. About one hundred of them. They arrived at the same time as the police and the military.189

These urban gangs destroy not only homes but also arbitrarily destroy residents’ personal property. Eva Sugiharto told Human Rights Watch about the courageous actions of her fourteen-year-old daughter when a gang carried out the eviction of their housing complex in Pasar Baru, Central Jakarta, under the watchful eye of the local authorities:

My oldest child arrived. She was very angry with [the thugs]. I was more scared, but she was shouting at them, telling them to be careful, to slow down. They were taking her computer out, but they destroyed her study desk. She kept shouting at them but I was just scared….My husband had a motorbike parked outside and one of them tried to smash the headlight and had already raised his stick in the air and my daughter stood in the way and yelled at them not to do it, and they didn’t.190

Gangs of thugs may also be involved in the intimidation of a community prior to an eviction. Setiono Muang, a fifty-year-old employee of the railway company, told us about the threats made on his community in Kampung Melayu where the government is attempting to acquire land so as to expand the existing railway tracks as part of the “Double-Double Track” infrastructure project:

We were intimidated for three full months by these guys with guns who were acting like they were police. We don’t know them by name but they’re hired thugs…[We think] these people were hired by the [local neighborhood official] to intimidate us to move. They were carrying pistols like the gun of police. No uniforms, they were in civilian clothes with longish hair. Hired thugs. They never talked seriously to people, but they’d say “Move away or else you will be arrested by the police” to people who passed by…[They] came every day. They started their rounds at seven o’clock in the morning, then they would walk around this street, then in the afternoon they would post themselves on the road. And then in the evening they would post themselves by the [local neighborhood official’s] house drinking alcohol. Then at midnight they would walk around again. Six people, always the same people.191

A gang was involved from the outset in the 2005 eviction of a community on Cakung Cilincing Road, in East Jakarta. Human Rights Watch asked Hariadi Tadji, a thirty-three-year-old who sells gasoline on the side of the road, whether his community had received any official notification that they were going to be evicted. He replied: “We had notification letters for the eviction. The first was from [this gang], and the second came from the sub-district office.”192 As Riduan Budiarti, a twenty-six-year-old salvager of waste metal, further explained, “The letter came directly from the [gang]. The letter was from the people who claimed to own the land [a group of businessmen], but it came through the [gang]; they delivered it.”193

Kersen Saptono told Human Rights Watch about the involvement of a gang known as Forum Betawi Rempung (FBR; Betawi Brotherhood Forum) following the eviction at Cakung Cilincing: “FBR erected the fence [around the site] five days before the Idul Fitri [holiday in October after Ramadan]. They were wearing FBR uniforms….They didn’t explain why they put up the fence.”194

One of the residents of Cakung Cilincing told Human Rights Watch how he was intimidated into accepting compensation at a level that he was unhappy with because of his fear of assault by FBR members:

We have received some money, but we were forced to accept it. I don’t know who the money is from, but it came through the [the local neighborhood official]. If we didn’t accept the money, we would have been attacked by FBR…I was terrorized by phone calls, saying “Whether you accept the money, or you don’t accept the money, you will still have to move.” The phone number of the person calling didn’t come up on my phone.195

Violence and Intimidation Against NGO Activists

Members of the Indonesian security apparatus have been involved in intimidating and using unnecessary force against members of groups who protest evictions, or who oppose legislation aimed at making it easier for the government to acquire land. Because these activists working with non-governmental organizations (NGOs) play a role in mobilizing concerted public opposition to forced evictions, government harassment of them, including the arbitrary arrest and detention of advocates or physical violence against them, infringes upon the rights to freedom of expression, peaceful assembly, and association, which are fundamental rights enshrined in Indonesian and international law.196

Berkah Gamulyan works as an advocate at a Jakarta NGO called the Urban Poor Consortium which promotes the rights of the city’s poorest residents. In a lengthy interview with Human Rights Watch he detailed his experiences being arbitrarily arrested and physically ill-treated by the police because of his role leading a demonstration opposing the new Presidential Decree intended to ease the ability of the government to acquire and clear land:

It was July 10, [2005]. This was one of our regular demonstrations…. Right around 3 p.m. they asked us to stop and leave the site. It was the intelligence agents, from the police, who came to us and asked us to show them our permission [to hold the demonstration]….After we told the Intel officers that we would not leave the site, we informed our friends that we would not leave. Then the head of the sub-district police came to me and asked me to disperse because, he said, we didn’t have permission. I told him that it had nothing to do with permission, because we didn’t need it, we just needed to notify the police of our intention [to demonstrate], and so we showed him the notification letter. We had faxed it twice, three days before and then one day before….And then the police surrounded our car. I was standing on the car across the street from the Presidential Palace. I was standing on the back of a pick-up, and the police surrounded the car. Some of them pulled me down. It was police in police uniforms…there were about fifteen police…surrounding the car, only some were wearing uniforms. Some were wearing civilian clothes. Maybe five in civilian clothes, the rest in uniform. Some of them came up…and pulled me down. They grabbed me by the arms and shirt to pull me down. I fell down and they started beating me. All the police in uniform. They were using their hands and feet. They hit me on the head, the chest. They kicked my back. Punched my face. Kicked my chest. Pulled my hair…The beating process maybe took two minutes. Maybe hit me ten times, I forget. They held my arms behind my back. Then tried to take me to their police car.197

According to Gamulyan, the police arrested eight NGO members:

They arrested…one of them because he had punched the police trying to protect me. [Another] three had formed a circle to protect the car. So four were arrested for trying to protect me….The last four were the driver and the three technicians of the sound system car, because [the police] took the car as evidence. They took us to the police station in Central Jakarta. They interrogated the eight of us until eight in the morning the next day….On the next day, six of the eight were released at 1p.m., because they were only witnesses.198

Human Rights Watch spoke with an Indonesian lawyer who confirmed that the protestors had indeed conformed with the legal requirements, as the Law on Freedom of Expression only requires that protestors give police notice prior to their demonstration and does not require a letter of confirmation from the police.199 Arresting people without grounds established in law is a violation of Indonesian and international law.200

Gamulyan went on to describe the physical and verbal abuse that the police inflicted on two of the NGO activists once they were all already detained at the police station:

Before the interrogation, between 4p.m. and 4:30p.m., two of the demonstrators were beaten in the room. I saw this. It was Eldon and Abdul [not their real names201] from the Urban Poor Consortium and [Environmental NGO] Walhi. The police were shouting at them, calling them bad words. We were in the same room. Eldon was beaten because he had earlier hit a police officer during [our arrest], so they were having revenge. They were beating Abdul because he had a big body, and a tattoo. It was two police officers, one by one. One punch from each police officer against each of them. Just one on one.202

Gamulyan also shared his own treatment at the police station:

On the first night, I was kept in the interrogation room. On the second night, I stayed in the temporary detention room where I was still allowed to wear civilian clothes….On the third and fourth night I was kept in the prison with the prisoner clothes….I was placed in the same room with…convicted criminals. Nine of us in the same room. All of them were convicted. The size of this room was like this mat [approximately six square meters]….I was released on July 14, at 7p.m. Until now, I have the same status, as a suspect, and all the [files] about me are ready to proceed to the court. It’s all in the police officers’ hands. We had another demonstration in November, about rising fuel pricing, and then I was arrested for twenty-four hours and they were telling me that I was still in the same status so I must be careful.203

International law requires that except in exceptional circumstances the government must segregate accused persons from convicted persons.204

A second case of intimidation of NGO activists that Human Rights Watch investigated involved a community organizer visited at night by two individuals who he believed were members of the government security forces who verbally intimidated him because of his efforts organizing opposition to an upcoming eviction. Irwan Naibaho heads a small community group that is advocating for better compensation for land being acquired for the East Canal Project. At an anniversary celebration for the organization, Irwan Naibaho gave a speech to the community members and local government officials in attendance:

I started by complaining, in a bit of a harsh way, about the non-transparent mechanisms of the project. I addressed that statement to the security forces officers. I dared to speak that day, to speak a bit harshly, at the officers, because I had the legal basis as a representative of the community. You have the right to represent a community as long as you get approval from the village official, and I had that approval…but afterwards…I already felt a bit worried, and then when I went home…there were two people outside my home. There were two guys, well built…they were saying that I was being too critical…they sat me in the middle between them in front of the house. I was asked to watch my words when I speak or when giving any statement. They were wearing brown uniforms. But I don’t know what kind of security forces….They just said that I should watch my statements.205

Human Rights Watch spoke to another NGO advocate beaten by public order officials while attempting to rally community residents to resist an eviction that was in progress and denouncing the eviction as illegal over a loudspeaker. Nurkholis Hidayat, a lawyer, recounted what happened at the eviction at Cakung Cilincing, on September 15, 2005:

There were about one hundred public order officials pulling down the houses with cables. I tried to meet their commander…I explained to him that the forced eviction was a violation of human rights and that this was an illegal eviction. I asked him for his letter giving him the authority to carry out the eviction. He could not answer…I tried to meet the head of the sub-district….He was commanding the public order officials…I told him that the forced eviction was a violation of human rights and was inhumane. But he…didn’t care about my warnings…I called the community together with a loud speaker. I said to them that this was an illegal eviction and that we should struggle to defend our rights. But then suddenly, while I was speaking, from the side of the road the public order officials and the police grabbed me around the neck with their arm. My t-shirt was ripped. I was with [my colleague], and both of us were taken by our necks by public order officials. They pulled us like animals. [The head of the public order officials] took me by the collar of my shirt from the front. I had been standing on a table…Five or ten public order officials pulled me down. The public order officers tried to hit me on my head….In the chaos, three police officials came to me, and tried to protect me from the public order officials—to block the punches. I don’t know who hit me. I saw around five or ten public order officials trying to hit me in my head, and I was just conscious that I had pain in my head…and then a police officer took me around the neck from behind, saying he would protect me…. Two police took me by the arms to…about 30 meters away…They dropped me on a chair under a tree. They were angry at me. They said “This is no good, you are the lawyers but if you confront the public order officials, it is dangerous for you.”206

Nurkholis filed a complaint with the police about this treatment, but has not received any official response from the authorities.

Evictions: Pisangan Timur, East Jakarta

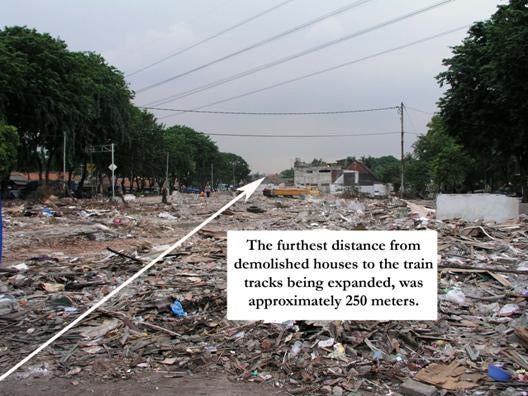

Human Rights Watch visited the community at Cipinang, Pisangan Timur, on two occasions. During our first visit we spoke with members of the community who had been evicted days earlier on January 4, 2006. We returned on January 12, 2006 when we witnessed the eviction of the remainder of the community. Residents and their families had lived on this land for generations. Eviction letters for the first eviction stated that the houses were to be demolished because they were built without permission. The letters, however, came from the government office of the “Double-Double Track” project—a project designed to add a second set of tracks next to the existing tracks—and local officials made public statements justifying the clearance on the grounds of this infrastructure project. A comparison of the location of the first eviction with the official design plan for the project, however, indicates that much of the area cleared is in fact well outside the boundaries of the project: the government cleared land as far as 250 meters from the train track (see Photo 6 on page 61), yet the “Double-Double Track”—a project partially funded by the Japan Bank for International Cooperation—is intended to occupy only a few meters of land on each side of the existing track. Both evictions were carried out by hundreds of public order officials, in the presence of both police and military. Destruction of the permanent houses was completed using a bulldozer. |

Photo 6: The eviction at Pisangan Timur cleared land approximately 250 meters from the train track scheduled for widening. The government claimed that the houses were to be demolished because they were built without permission. The eviction letters, however, came from the government office of the Double-Double Track project.

(c) 2006 Bede Sheppard/Human Rights Watch

147 Human Rights Watch interview with Rini Rumasilan (not her real name), interviewed January 20, 2006. Rini Rumasilan’s home in Cengkareng Timur was destroyed on September 17, 2003. Before the eviction she worked as a farmer, but after the eviction she does small trading.

148 Human Rights Watch interview with Jornal Effendi Siahaan, Deputy Head of Department for Public Order and Community Protection, January 26, 2006.

149 Human Rights Watch interview with Agus Adil (not his real name), interviewed January 11, 2006. Law enforcement officials may only use firearms against people when less extreme means are insufficient for self-defense, or for the defense of others against an imminent threat of death or serious injury, to prevent a particularly serious crime involving grave threat to life, or to arrest a person presenting such a danger who is resisting arrest. United Nations’ Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials, Adopted by the Eighth United Nations Congress on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders, August 27 to September 7, 1990, U.N. Doc. A/CONF.144/28/Rev.1 at 112 (1990), art. 9.

150 “Non-lethal” bullet is used to refer to metal pellets or plastic and rubber bullets which are substituted for live ammunition. Although they are sometimes referred to as non-lethal bullets in fact the large number of fatalities which have occurred when police forces have used such bullets has led to a number of police forces deciding not to use them.

151 Human Rights Watch interview with Pramana Prihatin (not his real name), Pondok Kopi, January 12, 2006.

152 Human Rights Watch interview with Kalarensi Aries (not her real name), a forty-four-year-old woman who runs a small food store, who was interviewed in the rebuilt community of Pondok Kopi on January 12, 2006. Kalarensi Aries’s home in Pondok Kopi was destroyed on October 29, 2001.

153 Human Rights Watch interview with Kalarensi Aries (not her real name), January 12, 2006.

154 Human Rights Watch interview with Pramana Prihatin (not his real name), Pondok Kopi, January 12, 2006.

155 Human Rights Watch interview with Rini Rumasilan (not her real name), January 20, 2006.

156 Human Rights Watch interview with Hariadi Tadji (not his real name), a thirty-three-year-old who sells gasoline on the side of the road, interviewed across the road from his demolished home on January 8, 2006.

157 Human Rights Watch interview with Kersen Saptono (not his real name), Cakung Cilincing, January 8, 2006.

158 Human Rights Watch interview with Herman Haryani (not his real name), a fifty-two-year-old unemployed Bajai driver, interviewed beside the tarpaulin shelter where he lives on January 22, 2006.

159 Human Rights Watch interview with Lusiana Angga (not her real name), interviewed on January 22, 2006. Before the eviction, she used to work teaching the Koran, but now is a housewife. Lusiana Angga’s home in Jembatan Besi was destroyed on August 26, 2003.

160 Human Rights Watch interview with Ani Fatah (not her real name), interviewed January 20, 2006. Ani Fatah’s home in Cengkareng Timur was destroyed on September 17, 2003. Before the eviction, she worked as a part time farmer and a part time tailor, but now she’s generally unemployed.

161 Human Rights Watch interview with Wawan Muliadi (not his real name), a seventeen-year-old who salvages for waste plastic in the river, interviewed January 14, 2006. Wawan Muliadi has been evicted from his home in Teluk Gong on numerous occasions between November 13, 2001 and January 4, 2006.

162 Human Rights Watch interview with Jornal Effendi Siahaan, Deputy Head of Department for Public Order and Community Protection, January 26, 2006.

163 Ibid.

164 Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, General Comment 7, para. 13.

165 Human Rights Watch interview with Jornal Effendi Siahaan, Deputy Head of Department for Public Order and Community Protection, January 26, 2006.

166 Human Rights Watch interview with Rini Rumasilan (not her real name), West Jakarta, January 20, 2006.

167 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia, Art. 28H(4), reads: “Every person shall have the right to own personal property, and such property may not be unjustly held possession of by any party.” The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, widely regarded as customary international law, also provides that “Everyone has the right to own property” and that “No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his property” (Art. 17).

168 Urban Poor Consortium, “Kampung Rawadas, Pondok Kopi, East Jakarta,” information sheet produced by Jakarta-based NGO, date unknown, given to Human Rights Watch, January 31, 2006.

169 Human Rights Watch interview with M. Berkah Gamulyan, advocate for the Pondok Kopi community, Urban Poor Consortium, January 17, 2006; “Hundred might lose their houses,” Jakarta Post, October 30, 2001.

170 Urban Poor Consortium, “Kampung Rawadas, Pondok Kopi, East Jakarta;” Human Rights Watch interview with Pramana Prihatin (not his real name), January 12, 2006.

171 Human Rights Watch interviews with Pramana Prihatin and Agus Adil (not their real names), January 12, 2006.

172 Ibid.; and Urban Poor Consortium, “Kampung Rawadas, Pondok Kopi, East Jakarta.”

173 Urban Poor Consortium, “Kampung Rawadas, Pondok Kopi, East Jakarta.”

174 Throughout this report, all figures quoted in rupiah have been converted into United States dollars using the exchange rate at the relevant date, and thus may vary throughout.

175 Human Rights Watch interview with M. Berkah Gamulya, advocate for the Pondok Kopi community, Urban Poor Consortium, January 17, 2006.

176 Human Rights Watch interview with Agus Adil (not his real name), Pondok Kopi, January 11, 2006.

177 Human Rights Watch interview with Sri Suharti (not her real name), a forty-three-year-old woman who runs her own small shop next to her house, interviewed under the railway tracks flyover where she still lives in Cikini, January 9, 2006. Sri Suharti’s home under the railway tracks flyover in Cikini was destroyed on March 12, 2005.

178 Human Rights Watch interview with Kersen Saptono (not his real name), Cakung Cilincing, January 8, 2006.

179 Human Rights Watch interview with Jullieta Indriyanti (not her real name), a forty-year-old salvager of second-hand materials, interviewed beside the blue tarpaulin tent she had recently erected for shelter, January 14, 2006. Jullieta Indriyanti has been evicted from his home in Teluk Gong on numerous occasions between November 13, 2001 and January 4, 2006.

180 Human Rights Watch interview with Soleh Atmaji (not his real name), Cikini, January 9, 2006.

181 Human Rights Watch interview with Arti Sudewo (not her real name), Cikini, January 9, 2006.

182 Human Rights Watch interview with Budi Santoso (not his real name), Pisangan Timur, January 7, 2006.

183 Human Rights Watch visit to Pisangan Timur during the course of an eviction, on January 12, 2006.

184 Human Rights Watch interview with Fajri Husen, Personal Assistant to FBR Central Management, January 29, 2006. The Indonesian expression was “Bagi mereka yang kurang ajar, mari kita hajar.”

185 Human Rights Watch interview with Eddie Hariyanti (not his real name), forty-eight years old and unemployed, interviewed while living in the courtyard of the National Commission on Human Rights, January 6, 2006. Eddie Hariyanti was evicted from his home in Siliwangi housing complex, in Pasar Baru, on December 21, 2005.

186 Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, General Comment 7, para. 9.

187 Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, General Comment 7, para. 15.

188 Human Rights Watch interview with Herman Haryani (not his real name), Jembatan Besi, January 22, 2006.

189 Human Rights Watch interview with Pramana Prihatin (not his real name), Pondok Kopi, January 12, 2006.

190 Human Rights Watch interview with Eva Sugiharto (not her real name), forty-three years old, interviewed while living in the courtyard of the National Commission on Human Rights, January 6, 2006. Eva Sugiharto was evicted from her home in Siliwangi, in Pasar Baru, on December 21, 2005.

191 Human Rights Watch interview with Setiono Muang, a fifty-year-old employee of the state railway company, interviewed among the rubble of his demolished community, January 16, 2006. Setiono Muang’s home in Kampung Melayu was destroyed on January 11, 2006.

192 Human Rights Watch interview with Hariadi Tadji (not his real name), Calung Cilincing, January 8, 2006.

193 Human Rights Watch interview with Riduan Budiarti (not his real name), a twenty-six-year-old salvager of waste metal, interviewed across the road from his demolished home on January 8, 2006. Riduan Budiarti’s home in Cakung Cilincing was destroyed on September 15, 2005.

194 Human Rights Watch interview with Kersen Saptono (not his real name), Cakung Cilincing, January 8, 2006.

195 Ibid.

196 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia, Art. 28E(3) reads: “Every person shall have the right to the freedom to associate, to assemble and to express opinions;” ICCPR, Arts. 19, 21, and 22.

197 Human Rights Watch interview with Berkah Gamulyan, advocate at Urban Poor Consortium, January 17, 2006.

198 Ibid.

199 Human Rights Watch interview with Taufik Basari of Jakarta Legal Aid Institute (LBH Jakarta), January 28, 2006.

200 ICCPR, Art. 9(1) reads: “Everyone has the right to liberty and security of person. No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest or detention. No one shall be deprived of his liberty except on such grounds and in accordance with such procedure as are established by law.”

201 Because Human Rights Watch was unable to meet with these individuals, we have chosen to use pseudonyms for them.

202 Human Rights Watch interview with Berkah Gamulyan, January 17, 2006.

203 Human Rights Watch interview with Berkah Gamulyan, January 17, 2006.

204 ICCPR Art. 10(2)(a).

205 Human Rights Watch interview with Irwan Naibaho (not his real name), a sixty-one-year-old unemployed man, interviewed January 29, 2006. Irwan Naibaho will be evicted as part of the land acquisition process for the East Canal Project.

206 Human Rights Watch interview with Nurkholis Hidayat, lawyer at Jakarta Legal Aid Institute, January 16, 2006.