V. Detention in Public Hospitals for Lack of Payment

Numbers of hospital detainees

Statistics kept by Burundian hospitals show that they have been struggling with the problem of unpaid bills for years, and that the detention of patients is not a new or ad-hoc measure.37 Hospitals short on funds began detaining patients unable to pay their bills in the 1990s,38 when cost recovery was already practiced in some health facilities, and have done so with increasing frequency since the wholesale introduction of the cost recovery system in 2002.

During 2005 hundreds of patients were detained in Burundian hospitals. Data from seven of the thirty-five public hospitals in Burundi combined show 1,076 cases of patients who were unable to pay their bills in 2005 (see table 1). This figure includes both those who were detained and those who managed to leave without paying their bills. Given that this sample represents only a fifth of the public hospitals in Burundi, the total number of patients unable to pay their bills was certainly far higher. At the Prince Régent Charles Hospital alone, 621 patients were detained during 2005. Of those, 354 patients had their bills eventually paid by benefactors, and the other 267 found a way to leave the hospital without paying.

Figures on unpaid bills at Roi Khaled Hospital show varying numbers since 2001 (see table 2), with an average shortfall of about U.S.$39,000 per year. At other hospitals, similar figures are not available, but there are statistics documenting the loss of income in 2005 (see table 3). At Prince Régent Charles Hospital, staff have also documented a steep rise in the number of bills paid by benefactors: a total of 44 for the three years 2001-03; 85 in 2004 alone, and 352 in 2005.39 It can be assumed that in most cases benefactors paid bills of patients who were unable to pay their bills and had been detained. It is likely that the rise represents a real increase in the number of hospital detainees, though other factors—such as increased media attention to the problem—might have exaggerated this trend. 40 Statistics of the much smaller Prince Louis Rwagasore Clinic show an increase in the number of indigent persons listed in their books: 11 in 2001, 18 in 2002, 16 in 2003, 16 in 2004, 39 in 2005 (table 4).

Table 1

Number of patients who did not pay their bills at seven Burundian hospitals in 2005

|

Roi Khaled Hospital, Bujumbura |

42241 |

|

Prince Régent Charles Hospital, Bujumbura |

26742 |

|

Ngozi Hospital, Ngozi province |

217 |

|

Bururi hospital, Bururi province |

36 |

|

Hôpital de Rumonge, province de Bururi |

36 |

|

Hôpital de Matana, province de Bururi |

51 |

|

Hôpital de Muramvya, province de Muramvya |

47 |

|

Total |

1076 |

Table 2

Unpaid bills at Roi Khaled Hospital, Bujumbura, 2001-2005 (FBU)

(1,000,000 FBU = approximately U.S.$1,000)43

|

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

|

23,334,446 |

64,150,549 |

34,297,612 |

25,666,425 |

47,769,382 |

Table 3

Unpaid bills at seven hospitals44 in 2005 (FBU)

|

Roi Khaled Hospital, Bujumbura |

47 769 382 |

|

Prince Régent Charles Hospital, Bujumbura |

24 498 99245 |

|

Ngozi Hospital, Ngozi province |

9 492 170 |

|

Bururi Hospital, Bururi province |

1 115 050 |

|

Rumonge Hospital, Bururi province |

2 174 350 |

|

Matana Hospital, Bururi province |

460 540 |

|

Muramvya Hospital, Muramvya province |

2 270 351 |

Table 4

Indigent46 patients and their bills at Prince Louis Rwangasore Clinic, Bujumbura, 2001-2005 (FBU)

|

|

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

|

Number of indigent patients |

11 |

18 |

16 |

16 |

39 |

|

Bills by indigent patients |

1,716,744 |

1,753,456 |

2,568,408 |

2,586,682 |

7,629,331 |

Medical problems leading to detention

Data from four hospitals show that during 2005, surgical patients represented about two-thirds of all indigent patients. The remaining one-third of indigent patients were mostly from two types of ward: internal medicine (16 percent) and pediatrics (10 percent). Of indigent patients overall, 35 percent were women who had delivered their babies by caesarean section.47

Surgery

It is not surprising that many victims of hospital detention were patients who had undergone surgery, given that surgery is often more expensive than ordinary medical care. In addition to women undergoing caesarean deliveries (discussed below), we interviewed several men who had suffered bad road accidents, a woman with breast cancer, and the mother of a baby who needed urgent surgery on the intestines.

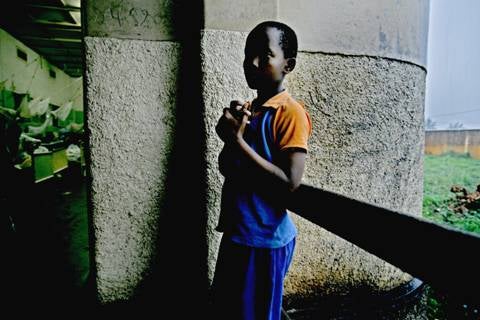

Félix M. has been in detained in Prince Régent Charles Hospital for over one year, after having already spent a year there for treatment. The thirteen-year-old boy was hit by a vehicle when he was playing with other children. He suffered a serious leg injury and underwent surgery. His father allegedly embezzled the insurance funds destined for his hospital care, and his mother had been unable to find a way to pay for the treatment. As of August 2006, Félix M. continued to be detained.

© 2006 Jehad Nga

Patients suffering from long-term or chronic diseases, including HIV/AIDS

Patients with long-term or chronic diseases also incurred high hospital costs that they could not pay and that resulted in their detention. People with chronic conditions are often unable to work and therefore depend on others to pay their hospital bills. One such example was Christian B., an 18-year-old young man who suffered from a serious skin disease. He was an orphan, and the uncle who was looking after him could not pay his hospital bill. He said local authorities refused to issue an indigence card for him, saying the card was not being used any more.48 Christian B. told us,

I have had a skin disease for about two years now. I went to Bujumbura for treatment but they refused to treat me, so I came here. I was given medicine at the hospital and it got better. I was put in an isolated room. I could not pay the bill but around Christmas 2005 I was released along with other people. I had a bill of over 240,000 FBU [$240]. Now the illness has come back. I came back to the hospital.49

There are about 220,000 people50 living with HIV/AIDS and 46,000 people in need of AIDS treatment in Burundi, and many of them also face detention in hospital.51 The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria is currently providing about $21 million to the Burundian government for treatment and prevention. Under this program, antiretroviral drugs are provided for free.52 The World Bank runs a multi-sector program on HIV/AIDS in Burundi of $36 million over a period of four years.53 But even with this level of international assistance, only about 6,400 persons received the life-saving drugs without cost in 2005, while about 40,000 more needed the drugs but were unable to benefit from them due to the inaccessibility of treatment sites and other reasons.54 Many of those without antiretroviral drugs seek medical care for opportunistic diseases such as tuberculosis, pneumonia, fungal infections or other diseases, and they usually have to pay for treatment.55 According to the medical director in the Ministry in Charge of the Fight against AIDS, around 70 percent of internal medicine patients have HIV/AIDS.56 Records of four hospitals show that about 15 percent of all indigent patients in 2005 were internal medicine patients (see table 5).

Because of reluctance to discuss AIDS and absence of any indication on hospital records, we collected no data on the frequency with which AIDS patients were detained for unpaid bills.

We spoke to one patient who identified herself as suffering from AIDS. She was detained for two months for failing to pay for treatment for a fractured arm and leg.57

Table 5

Number of patients unable to pay their bills58 by ward

(medical department) in 2005

|

|

Roi Khaled Hospital, Bujumbura |

Prince Louis Rwagasore Clinic, Bujumbura |

Prince Régent Charles Hospital, Bujumbura |

Muramvya Hospital, Muramvya province |

|

Total |

422 |

39 |

267 |

47 |

|

Gynecology/ Obstetrics |

91 |

24 |

137 |

15 |

|

Surgery |

100 |

6 |

47 |

13 |

|

Internal Medicine |

64 |

1 |

42 |

14 |

|

Pediatry |

48 |

4 |

22 |

3 |

|

Intensive Care and Emergency |

46 |

1 |

6 |

0 |

|

Operating theatre (anaesthetics etc.) |

64 |

3 |

5 |

2 |

|

Other |

9 |

0 |

8 |

0 |

This newborn boy urgently needed surgery after birth. As the mother could not pay for it, she and the baby got detained at Roi Khaled Hospital.

© 2006 Jehad Nga

Maternal health problems before May 1, 2006

Before the presidential order on maternal and child health care on May 1, 2006, a significant proportion of hospital detainees were women who had suffered complications in connection with the birth of a child, such as those who delivered by caesarean section.

While 35 percent of indigent patients unable to pay their bills were women who had recently given birth, the situation varied considerably by hospital.59 At the time of one visit to Prince Louis Rwagasore Clinic to research this report, in February 2006, all the detainees were women who had delivered by caesarean section, and according to the guards, this was often the situation.60

At 1,000 deaths per 100,000 live births, the maternal mortality rate in Burundi is alarming. About 80 percent of deliveries take place at home without the assistance of a trained health professional.61 There is no functioning referral system that ensures timely access to hospitals in case of complications. Emergency obstetric equipment is not available as widely as it should be. Research has shown that lack of access to emergency obstetric care is one of the main causes of maternal mortality worldwide.62

Infant and child health problems

Another important group among those detained—about 10 percent—were infants and children. As mentioned above, infant and child mortality rates in Burundi are among the highest in the world. This is due in large part to malaria, diarrhea, pneumonia, and HIV/AIDS.

Malaria is responsible for 50 percent of hospital deaths of children under age five. Acute respiratory illness and diarrhea are also frequent causes of death in young children, mostly due to the lack of potable water, inadequate sanitation, and poor housing conditions. About 44 percent of children are malnourished or stunted, and 56 percent suffer from anemia. Approximately 27,000 children under the age of fifteen have HIV/AIDS. Immunization rates for the deadliest childhood diseases have declined in recent years.63 Experts have found that about two-thirds of child deaths could be averted if proven existing health interventions could be made available.64

The introduction of free health care for women giving birth and children under five constitutes an important step towards improving maternal and infant health, and ending detention among patients of this vulnerable group.

A young mother and her newborn baby, detained at Prince Louis Rwagasore Clinic following a caesarean section.

© 2006 Jehad Nga

“Since you have not paid, we will imprison you”: Experiences of patients

The moment when hospital staff hand patients their bill can mark the transition from hospital treatment to hospital detention. Hospital staff—mostly nurses and doctors—impose the detention and attempt to justify it to the patients. Hospital managers—medical doctors as well as administrators—also justified the detention to Human Rights Watch researchers.65 Hospital staff may detain patients because they believe it is necessary in order to keep the hospital functioning. Nonetheless, in doing so they violate their own ethics66 and their conduct leads to a breach of trust in a privileged relationship. They also become agents of a human rights abuse.

Christine K., an 18-year-old who gave birth by caesarean section, recounted her experience. At the time of the interview she had been three weeks in detention. She said,

When I got the bill, the doctor said to me, “Since you have not paid, we will imprison you.” Life here is difficult. I don’t have permission to leave with my baby. We are often hungry here. I cannot stand this situation any longer. 67

Pierre B. is a middle-aged man who was hit by a car when walking home after church service in November 2005, and held for one month at Prince Régent Charles Hospital when we spoke to him. He explained,

My leg and face were crushed. I was unconscious for one day. In January, I was given a bill of 205,445 [FBU, $205]. When I said that I cannot pay this, I was told to stay.68

Josephine C., whose baby was sick, tried to plead with the hospital director for her release but he only confirmed her detention:

I spoke with the director of the hospital and I told him that I couldn’t pay. He said that I cannot leave the hospital, that I have no right to leave the hospital until I paid the bills.69

A young mother and her newborn baby, detained at Roi Khaled Hospital following a caesarean section.

© 2006 Jehad Nga

Some patients, such as Josephine C., knew about the risk of detention. Other patients were caught off guard by the high costs of their treatment. Claudine N., an 18-year-old mother of two, did not expect a high bill for the delivery of her baby. At the time of the interview, she had been held for six weeks:

I got the bill on December 28, 2006, and it was over 116,000 FBU [$116]. I did not expect that because Roi Khaled is a public hospital. The doctor said to me, “We cannot do this differently, you have to stay here.”70

The length of detention of patients varied greatly, depending in part on whether the patient can find a benefactor to pay the bill or find a way to evade surveillance and leave. Most patients interviewed were detained for a period of several weeks or months, but a few were kept for about a year.

Surveillance

In most hospitals, detained patients are able to move around the building but are prevented from leaving the premises by security guards from private security companies contracted by the hospitals.71 According to several patients, security guards on the grounds generally knew the names and faces of those detained, often because they had been pointed out to them by hospital staff. Several detainees said guards followed them around even within the hospital premises.72 As a consequence, patients could not leave even for a moment, unless they got express permission to do so. As one victim put it, “I am detained because I cannot pack up my things and leave. To leave means to escape.”73

Théodore N. was detained for two weeks in Prince Régent Charles Hospital after he received treatment for an accident injury. He told us,

I am really imprisoned here. One day, I tried to get out of the hospital and I was stopped because I have not paid my bill yet. When I see a doctor, I always ask to leave, since I am not getting any medical treatment. The guards threaten me. Whenever I come near the exit, they tell me that I cannot leave because I have not settled the bill.74

Patients in other hospitals had similar experiences. A patient who was held for three months in Gitega Hospital complained that whenever he would leave his bed to sit in the sunshine, guards or other hospital staff would come and ask him where he was going.75

A patient detained at Prince Régent Charles Hospital. © 2006 Jehad Nga

At Ngozi Hospital, the director of finance and administration explained how surveillance by a private security company is essential. Either patients stay until they find someone who pays, or—if they flee—the company pays a fine. Because of the large numbers of people escaping, the hospital has negotiated a modus vivendi with the security company, reducing the fine to a sum that is acceptable to them:

We have come to an arrangement with the security company. For us, [using the security company] is a way of cutting down on the costs. Otherwise the hospital would have to be shut down.76

Seventeen-year-old Félicité G. had been held for two weeks at Ngozi hospital when she spoke to us. She described what surveillance meant for her:

I am detained because I cannot gather the money to pay the bill. I cannot leave or move around. I am watched everywhere because they always think I want to escape. But it is not good to run away. When they catch you, you cannot go back for treatment. I would be punished for that.77

Other detainees in Ngozi and elsewhere confirmed that they did not escape because they feared that they or their children might fall ill at some future time and be refused treatment.78 They preferred to stay detained in the hospital than to risk having no possibility of hospitalization during the next illness.

Nevertheless, some patients found ways to leave hospital. At Prince Régent Charles Hospital, 191 did so between January and August 2005. Many left at night, and one person had left disguised in the clothes of a Muslim woman.79 According to one patient, two persons caught trying to leave surreptitiously were mocked and insulted by nurses.80

Prince Louis Rwagasore Clinic: Detention in a lock-up

Detainees at Prince Louis Rwagasore Clinic are held in a separate room with a guard at the door and are not allowed out of the room. When visited by researchers on February 14, 2006, about 20 people were in the room, about a dozen mothers with newborn babies who were confined there, plus some family members who were assisting or visiting them. A filthy toilet and shower constituted the sanitary facilities for all the detainees and visitors.

Agnès I., a 23-year-old woman who delivered her baby by caesarean section on January 17, 2006, could not pay her bill equivalent to $235 and so was moved to the lock-up, where she had stayed for one month when we spoke to her. She said she was told to stay in the room until she found money or a benefactor. She continued, “I have tried to get the money together but I have not managed. I stay here, I cannot get out. I cannot even go out to dry the clothes I have washed.”81

According to those guarding the room, most detainees were women who had had birth complications. Many were held until the babies were able to hold up their heads, meaning two or three months. When patients left without paying, the guards sometimes followed them home.82

At Prince Louis Rwagasore Clinic, detainees are held in a separate room with a guard at the door. At the time of our visit, the room held about twenty people. The sanitary conditions in the room were deplorable: there was a filthy toilet and a shower, and they could not be used in private because they belonged to the room. One person who had been held for a month, said: “After I got the bill I was directly taken here and told ‘Stay here. When you have money or there is a benefactor, you can leave.’” © 2006 Jehad Nga

Size of bills

Bills vary in size according to the services received by the patients. Even amounts that seem relatively small may exceed the monthly income of a poor Burundian. Félicité G., a 17-year-old mother, was held at Ngozi Hospital because she could not pay the equivalent of $9 for the treatment of her baby, who was sick with malaria.83 At the opposite extreme, David S. from Rutana province was hospitalized after he had a bicycle accident, and now faced a bill equivalent to $1,750, an enormous sum by the standards of ordinary Burundians. He said,

We arrived in Gitega hospital on June 15, 2004. At that moment I had nothing because the rebels had come to my house and looted almost everything. I was operated [on] here, but there was no improvement. Three months ago, they came to see me and told me to pay… 1,750,000 FBU [$1,750]. I don’t see how I can pay this bill, because I do not even have a plot of land that I can sell.84

When the bills are very high, it is harder to find benefactors. Therefore, patients who have had costly surgery or other expensive treatment are likely to be held for longer.

Conditions of detention

Lack of medical treatment

Hospital officials sometimes refuse further treatment to patients who have shown themselves unable to pay the cost of their medical care. At Prince Louis Rwagasore Clinic two young mothers who were detained following caesarean deliveries asked medical staff to treat their newborn babies, who had respiratory problems and were vomiting. According to the women, the staff refused. They said that doctors and nurses never entered the lock-up at Prince Louis Rwagasore Clinic.85

Michelle N., whose case was mentioned earlier, gave birth to a stillborn baby at Prince Régent Charles Hospital and was unconscious for two days after the birth. When she could not pay the bill she was moved to ward nine where many detainees were kept, and where she stayed for about ten weeks. There was no assistance from medical staff:

I got a fever and asked for treatment, but it was refused. The nurse said that I would have to pay the 10,000 FBU [$10] admission fee to obtain the registration form. Luckily the fever went away.86

At Gitega Hospital, nurses allegedly went one step further and refused to remove the stitches that closed the incisions from caesarean deliveries. If stitches are not removed, the incision may get infected. Emérite N., a poor farmer from Mwaro province, gave birth at Gitega hospital to a child who died after two weeks. In addition to coping with her grief, she was overwhelmed by a bill equivalent to $45 that she was unable to pay. She said, “I was told that they cannot remove the stitches until I have paid the bill. The stitches are now hurting. I worry that I will get an infection, and I feel trapped here.”87

Sometimes hospitals also refuse to carry out treatments on patients who will be unable to pay the costs, probably because they want to avoid expenditures which they will not be able to recover. Dorothée H., a widow who had recently returned from living as a refugee in Tanzania, was taken in by a family in Bujumbura and survived by selling tomatoes. She had the misfortune to fall and break her hip but did not seek treatment immediately. When her condition worsened, she said she went to two private clinics where she was refused, at the second one because she lacked the equivalent of roughly $100 needed for the admission fee. She entered a public hospital where doctors did some tests and advised surgery to replace her hip. Since the cost would be $400, clearly beyond her means, the surgery did not take place. Unable to pay her bill, even without the surgery, she remains in the hospital where she can hobble only a few steps at a time with the help of a cane.88

Lack of food

Almost all detainees complained of hunger. Hospitals in Burundi generally do not provide meals to patients, who depend on family members, charities or benefactors to give them food and drink. Human Rights Watch observed that those detained were particularly affected, due to their indigence and the length of their stay at the hospital, and those who had no family members nearby and willing to help or who did not find assistance elsewhere just went hungry. Agnès I., a young mother who had undergone a caesarean delivery, said that her relatives only rarely brought food and that patients had to buy even the water needed to make coffee or tea.89 Another young mother who had been detained for two months at a different hospital said, “For me it is difficult to get food. My family is tired of bringing food here. I have not even had tea today. I am waiting for God’s help.”90

In some hospitals, nuns provided food once a day to detainees who were grateful but pointed out that the food was of poor quality and insufficient in quantity, in particular for patients recovering from illness or surgery.

Losing the bed

Sometimes detained patients had to vacate their beds for patients who could pay. Gabriel N., mentioned above, told us after five weeks of detention at Roi Khaled Hospital:

I feel like I am in a prison here. I lost my bed last night to a sick person who could pay. So I slept on the floor. I don’t know when I will have another bed. They promised me that when a sick person leaves, I will get a bed.91

Several detained persons in Ngozi Hospital complained of the same practice.92 Christian B., the young man with a serious skin disease, mentioned above, who was hospitalized at Nogzi for about six months in 2005, was detained for non-payment of a bill of over $240. He reported having to sleep on the cement floor when paying patients arrived needing a bed.93 Also in Ngozi Hospital in March 2006, four other detained patients had been obliged to vacate their beds. One was a 65-year old widow. Two others were 17-year-old Félicité G. and 20-year-old Valentine Z., both of whom were sleeping on thin mats on the cement ground with their babies.94

Children in hospital detention

Children are not spared from hospital detention. Mothers stay with babies and small children while older children are sometimes held by themselves, with little or no support from the hospital.95

Mohamed S.

Three-year-old Mohamed S. was burnt badly all over his body when he was playing with other children and they accidentally tipped over a pot of boiling beans. At the time he was visiting his grandmother, who took him to hospital and had stayed with him since. They arrived at the hospital on November 16, 2005, and were detained for about six weeks when they spoke to us. Mohamed’s grandmother told us,

I received a first, incomplete bill at the end of December. It was not complete because they continued treatment. I was afraid of seeing it. It was more than 400,000 FBU [$400]. I have asked for the final bill because I am worried about the amount of money. We have been told we are not allowed to leave, even though the boy is now healed.96

The situation has been particularly difficult for the grandmother because her son, the child’s father, holds her responsible for the accident and refuses to provide money for the hospital costs.

Three-year-old Mohamed S. was burnt badly all over his body when he was playing with other children and they accidentally tipped over a pot of boiling beans. At the time he was visiting his grandmother, who took him to the hospital and stayed with him since. When we met them, they had been detained in Roi Khaled Hospital for six weeks. Mohamed’s grandmother, who can be seen in the background, explained: “We have been told we are not allowed to leave, even though the boy is now healed.” © 2006 Jehad Nga

Noah B.

Thirteen-year-old Noah B. was injured while playing football with his friends. He broke some bones in his ankle and needed surgery. He is one of eleven children and his parents are farmers. His mother and siblings stayed in their home province of Muramvya while Noah’s father accompanied him to Roi Khaled Hospital in Bujumbura and took care of him there during the treatment and the detention that followed. At the time of the interview, Noah B. had been held for about six weeks. His father told us,

We owe 438,785 FBU [$438] for Noah’s surgery. We are waiting for a benefactor because we will never have that much money…. The situation now is very hard. I have pretty much abandoned my house because I have spent all my time here. I have two younger children at school but I had to abandon everything and leave it all behind to be in the hospital with Noah.

I am free, I can come and go from this hospital, but my son cannot leave. He cannot escape. The doctors threaten us, telling us that soon Noah will lose his bed and will have to sleep on the floor so that a paying person can have the bed.97

Noah told us that he was in his first year of school when the injury happened, and that he wants to return to school as soon as possible.98

Félix M.

Félix M., aged 13, has been detained at Prince Regent Charles Hospital for over a year, after having already spent a year there for treatment for injuries suffered when a vehicle belonging to the African Union mission in Burundi struck him in July 2004. His father spent or used the money provided by the United Nations Operation in Burundi (ONUB), the successor agency to the African Union, for the boy’s care. His mother, who struggled to find the money necessary to pay just for Felix’s medicine, was unable to find a way to pay the rest of the hospital charges. Felix said,

I was in seventh grade in school but now I am not going to school any more. Now I am healed, there is just one small injury left. My family cannot pay the bill. I have been told that I cannot leave unless the bill is paid. I am detained here because I cannot go past the exit. The nuns give me food twice a day.99

The truth of Felix’s predicament emerged as a result of research done for this report.100 Although Felix’s father admitted to taking the money, he had nothing left of it.101 As of August 2006, Felix was still detained at the hospital.

Adèle A.

Twelve-year-old Adèle A. from Cibitoke province suffered a broken leg in an automobile accident in January 2006 when returning home from school. Following surgery, she had been detained for over four months at Prince Régent Charles Hospital when we interviewed her. She said,

I have no father and my mother is a farmer. My mother stays with me in the hospital here and tries to find things for us to eat. It is very hard. We have no family here, everyone is back in Cibitoke. We have no land so we cannot sell anything to pay the bills. Even to cultivate crops, we rent a plot. Right now, I have my bed but I am afraid that I will lose it. The conditions here in the hospital are very difficult. Sometimes I go for two weeks without soap… No one told me that if I couldn’t pay, I would have to stay in the hospital. It’s just accepted as normal that you just cannot leave if you haven’t paid the bill.102

Refusal to release dead bodies

When patients die and medical bills have not been settled, hospitals frequently refuse to hand over the bodies to family members. As a burial according to Burundian tradition becomes impossible, it is hard for mourners to express their grief in culturally acceptable ways. Francine U. died in December 2005 of malaria during pregnancy. The nurse at Roi Khaled Hospital who cared for her said:

She came too late, and she died. Her brother was with her but he left when she died. He did not pay her bill so her body stayed in the morgue. She is still there.103

The nurse confirmed that bodies are often held in the morgue for long periods if relatives cannot pay the bills, but said that if there are bodies at the morgue for a very long time, eventually “the hospital management will deal with it and bury them.”104 According to research by APRODH, there were seven bodies held at the morgue of Roi Khaled Hospital in August 2005. The relatives of the deceased had not paid the bills, which totaled more than $1,400.105

37 Hospitals often document the financial loss they incur, but usually do not document numbers of detained patients. Most statistics show how many bills have been left unpaid, and provide information on the cases of the patients, as well as about benefactors. Some hospitals also document the number of escapees. There is no standard breakdown that hospitals must follow, and statistics vary in detail and format.

38 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with director and other managers, Prince Louis Rwagasore Clinic, Bujumbura, February 14, 2006.

39 Figures obtained from hospital records.

40 See section X, below, on the dilemma of being a benefactor.

41 Data for the month of April are missing. Handwritten additions to the statistics of June 2005 have not been taken into account.

42 Data for the month of December are missing. The figure is based on lists of unpaid bills by escaped patients.

43 http://finance.yahoo.com/currency (accessed August 24, 2006)

44 According to records kept by the hospitals themselves. There is no standard format for the hospitals so the statistics vary in detail and format.

45 Unpaid bills by escaped patients, January-November 2005.

46 The hospital has kept statistics of indigent patients who were unable to pay their bill. However some settled them later, for example when they found benefactors.

47 See table 5. This figure is based on cases listed in three separate sections, gynecology/obstetrics, surgery, and operating theatre.

48 See below, section VIII.2, on exemption systems.

49 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with Christian B., Ngozi Hospital, Ngozi, February 16, 2006. It was unclear how long the period of detention—after he received the bill—was.

50 “Treatment Map Burundi,” IRIN, January 2006, http://www.plusnews.org/AIDS/treatment/Burundi.asp (accessed August 1, 2006).

51 Numbers provided by “Progress on Global Access to Anti-Retroviral Therapy, A Report on “3 by 5” and Beyond” (WHO, 2006), p. 72, http://www.who.int/hiv/fullreport_en_highres.pdf (accessed July 27, 2006). The IRIN Treatment Map suggests a lower number of people are in need of antiretroviral treatment, about 25,000; however it is slightly older and probably based on older figures.

52 The original program was about $8 million. In May 2006 the Global Fund decided to give an additional $13 million for the fight against HIV/AIDS, http://www.theglobalfund.org/programs/search.aspx?lang=en (accessed May 18, 2006).

53 Multisectoral HIV/AIDS Control and Orphans Project – Burundi, http://web.worldbank.org/external/projects/main?pagePK=64283627&piPK=73230&theSitePK=343751&menuPK=343783&Projectid=P071371 (accessed July 26, 2006).

54 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with representative of an NGO assisting AIDS patients, Bujumbura, February 17, 2006.

55 There is however a special program for the treatment of tuberculosis, so some patients might not have to pay for such treatment. Human Rights Watch telephone interview with medical director in the Ministry Charged with the Fight against HIV/AIDS, Bujumbura, May 19, 2006.

56 Ibid. Earlier statistics point to similar figures. In 1995, an estimated 70 percent of in-patients at Prince Regent Hospital were HIV positive. See: Confronting AIDS: Public Priorities in a Global Epidemic, A World Bank Policy Research Report (Oxford University Press, 1997), http://www.worldbank.org/aidsecon/arv/conf-aids-4/ch4-1p2.htm (accessed May 18, 2006), table 4.4.

57 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with Spéciose N., Bujumbura, February 23, 2006.

58 The statistics of Prince Louis Rwagasore Clinic include some cases of indigents who could not pay initially, but eventually found a way to settle the bill.

59 See table 5.

60 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with guards, Prince Louis Rwagasore Clinic, Bujumbura, February 14, 2006.

61 WHO, “Burundi, Health Sector Needs Assessment.”

62 L.P. Freedman, “Using human rights in maternal mortality programs: from analysis to strategy”, International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, vol. 75 (2001), pp. 51-60; Millennium Project, Task Force on Child Health and Maternal Health, “Who’s got the power? Transforming health systems for women and children,” http://www.unmillenniumproject.org/documents/maternalchild-complete.pdf (accessed July 31, 2006), pp. 5-6.

63 UNICEF, Burundi Statistics; WHO, “Heath Action in Crises – Burundi,” http://www.who.int/hac/crises/bdi/background/Burundi_Dec05.pdf (accessed July 28, 2006); WHO, “Burundi, Health Sector Needs Assessment.”

64 Millennium Project, Task Force on Child Health and Maternal Health, “Who’s got the power?” pp. 5-6.

65 See section below on the government response.

66 As in many other countries, doctors in Burundi take an oath as the basis of their ethics. It is called the Geneva Declaration (Serment de Genève) and is a modern version of the Hippocratic Oath. Among other things, it says “The health of my patients will be my first consideration; … I will not permit considerations of age, disease or disability, creed, ethnic origin, gender, nationality, political affiliation, race, sexual orientation, social standing or any other factor to intervene between my duty and my patient; … I will not use my medical knowledge to violate human rights and civil liberties, even under threat.” See English and French versions at http://www.wma.net/e/policy/c8.htm (accessed August 8, 2006).

67 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with Christine K., Prince Louis Rwagasore Clinic, Bujumbura, February 14, 2006.

68 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with Pierre B., Prince Régent Charles Hospital, Bujumbura, February 13, 2006.

69 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with Josephine C., Prince Régent Charles Hospital, Bujumbura, February 13, 2006.

70 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with Claudine N., Roi Khaled Hospital, Bujumbura, February 11, 2006.

71 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with Michèle N., Bujumbura, February 14, 2006; Unpublished document on hospital detention by international organization, August 2005. At Prince Régent Hospital detained patients are often moved to ward nine but are permitted to move about elsewhere in the building.

72 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interviews with Théodore N., Prince Régent Charles Hospital, Bujumbura, February 13, 2006; Michèle N., Bujumbura, February 14, 2006; Félicité G. and Valentine Z., Ngozi Hospital, Ngozi, February 15, 2006.

73 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with Amélie B., Roi Khaled Hospital, Bujumbura, February 11, 2006.

74 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with Théodore N., Prince Régent Charles Hospital, Bujumbura, February 13, 2006.

75 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with David S., Gitega Hospital, Gitega, February 16, 2006.

76 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with financial and administrative director, Ngozi Hospital, Ngozi, February 15, 2006.

77 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with Félicité G., Ngozi Hospital, Ngozi, February 15, 2006.

78 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interviews with Célestine H., Amélie B., Claudine N., Roi Khaled Hospital, Bujumbura, February 11, 2006. Human Rights Watch/APRODH interviews with Michèle N., Bujumbura, February 14, 2006.

79 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with financial and administrative director, Prince Régent Charles Hospital, Bujumbura, February 10, 2006.

80 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with Michèle N., Bujumbura, February 14, 2006.

81 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with Agnès I., Prince Louis Rwagasore Clinic, Bujumbura, February 14, 2006.

82 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with guards, Prince Louis Rwagasore Clinic, Bujumbura, February 14, 2006.

83 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with Félicité G., Ngozi Hospital, Ngozi, February 15, 2006.

84 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with David S., Gitega Hospital, Gitega, February 16, 2006.

85 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interviews with Agnès I. and Christine K., Prince Louis Rwagasore Clinic, Bujumbura, February 14, 2006.

86 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with Michèle N., Bujumbura, February 14, 2006.

87 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with Emérite N., Gitega Hospital, Gitega, February 16, 2006. Another woman reported the same refusal by nurses to remove the stitches in her incision. Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with Berthilde N., Gitega Hospital, Gitega, February 16, 2006.

88 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with Dorothée H., Prince Régent Charles Hospital, Bujumbura, February 13, 2006.

89 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with Agnès I., Prince Louis Rwagasore Clinic, Bujumbura, February 14, 2006.

90 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with Amélie B., Roi Khaled Hospital, Bujumbura, February 11, 2006.

91 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with father of Noah B., Roi Khaled Hospital, Bujumbura, February 11, 2006.

92 APRODH interview with hospital staff, Bururi Hospital, Bururi, March 2006.

93 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with Christian B., Ngozi Hospital, Ngozi, February 16, 2006.

94 APRODH interviews with Régine K. and Joëlle N., Ngozi Hospital, Ngozi, March 15, 2006.

95 In this report, “child” refers to anyone under the age of eighteen. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, to which Burundi is a party, states: “For purposes of the present Convention, a child is every human being below the age of eighteen years unless under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier.”

96 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with grandmother of Mohamed S., Roi Khaled Hospital, Bujumbura, February 11, 2006.

97 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with father of Noah B., Roi Khaled Hospital, Bujumbura, February 11, 2006.

98 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with Noah B., Roi Khaled Hospital, Bujumbura, February 11, 2006. There are many reasons why children in Burundi may go to school later than the usual age for primary school, including insecurity during the war and the government’s waiving of school fees during 2005.

99 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with Félix M., Prince Régent Charles Hospital, Bujumbura, February 13, 2006.

100 Human Rights Watch interview with Charles Atebawone, chief, Claims/Property Survey Unit, ONUB headquarters, Bujumbura, March 7, 2006.

101 Human Rights Watch interview with mother of Felix M., Bujumbura, May 11, 2006.

102 Human Rights Watch interview with Adèle A., Prince Régent Charles Hospital, Bujumbura, June 23, 2006.

103 Human Rights Watch/APRODH interview with nurse, Roi Khaled Hospital, Bujumbura, February 11, 2006.

104 Ibid.

105 Association Burundaise pour la Protection des Droits Humains et des Personnes Détenues, “Projet : secours aux indigents emprisonnés dans les hôpitaux,” September 2005.