<<previous | index | next>>

III. Attacks on Schools, Teachers, and Students

The tactics of the Taliban have changed. Now there are attacks on mullahs and teachers. Things are much worse.

—A teacher from Kandahar province96

When President Karzai stated in March 2006 that some 100,000 Afghan children who had gone to school in 2003 and 2004 no longer went to school, he said that this was in part “because some two hundred schools that we built were torched or destroyed.”97

In fact, the number of schools put out of commission is even higher. Listing schools that were closed in 2005, provincial and district education officials told us of at least forty-nine in Kandahar,98 fourteen in Ghazni,99 and eighty-six in Zabul.100 In January 2006, the director of education for Helmand province told journalists that 165 schools had been closed for security reasons.101 According to Nader Nadery, of the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission, “more than three hundred schools have been burned or, for the major part, have been shut down. . . . Most of the schools have been closed because of the fear of attacks by Taliban and Al-Qaeda forces, and, due to the insecurity that the people in the region [feel], parents are refusing to send their kids to schools.”102

Attacks against schools, teachers, and students rose markedly in late 2005 and the first half of 2006. Human Rights Watch recorded at least 204 reported physical attacks or attempted attacks (such as bombs planted but found before they exploded) on school buildings from January 1, 2005 to June 21,2006, based on reports to ANSO, the United Nations, the media, and our own interviews.103 Of these attacks, 110 occurred in the first half of 2006. This represents a significant increase in attacks reported to ANSO or otherwise recorded by Human Rights Watch in previous years.104 Although Human Rights Watch was not able to independently verify most of these reports, our count for 2006 is essentially consistent with that of the World Food Programme, which stated that as of June 19, 2006, 119 schools had been attacked in 2006, “seventy-two of them completely or partially burned, and twenty-five have been subject to threats.”105

Who and Why

Schools in Afghanistan have historically been targets of violence directed at the central government or perceived foreign interference (and frequently, both). In the current environment, the perpetrators of attacks on teachers and schools, and their motives, vary.

In several cases that Human Rights Watch independently investigated, we were unable to determine with certainty who was behind the attacks or why schools and school personnel were targeted, but certain general conclusions are possible. As set out above, insecurity in Afghanistan has a variety of sources and the people we spoke with identified a combination of motives. These fall into three overlapping categories: first, opposition to the government and its international supporters by Taliban or other armed groups, chief among them veteran anti-government warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, (and including, at times, regional warlords with local grievances and criminal groups trying to restrict government activity); second, ideological opposition to education other than that offered in madrassas (Islamic schools), and in particular opposition to girls’ education; and third, opposition to the authority of the central government and the rule of law by criminal groups—particularly those in the narcotics trade—anxious to avoid interference with their activity.

In many instances opposition forces or criminals attack schools and teachers as easy to reach symbols of the government (and often the only sign of the government in the area). Armed oppostion groups have changed their tactics to attack “soft targets,” that is, low level government employees and symbols of government presence.106 Teachers and schools, often isolated in rural areas, and with little or no security, present perfect targets for such attacks.

Another method of frustrating government policies is to stymie development projects. Opposition groups have explicitly adopted this position in some instances and targeted development agencies and NGOs. In several recent instances, opposition forces have killed foreign and Afghan staffers of development groups. The Taliban are most often blamed for these attacks, but it seems that other groups, at times with local grievances, or criminal groups eager to keep government influence at bay, are also responsible. For instance, ANSO reported that on February 4, 2006, in Saydabad district of Wardak province, “unknown men distributed night letters [threatening letters often left in public places at night] in the area. The night letter asked Afghans to join jihad and not to work for foreign organizations and the Afghan government. There was a specific warning to drivers who are transporting goods for organizations and government that they will be face severe consequences if they continue.”107 It is possible that the Taliban issued this warning; on the other hand, the area is quite close to Kabul and is dominated by forces allied with Abdul Rabb al Rasul Sayyaf, a radical warlord with a history of abusive behavior and now a prominent member of the Afghan parliament.108 Wardak was also the site of several attacks on schools in 2005, which a local government official there attributed to “[p]eople trying to stop the improvement of this place. They target schools because of improvement.”109 Such warnings and attacks serve to maintain or strengthen local forces by weakening government authority.

Some attacks appear to be the result of tribal or private disputes surrounding the local disbursement of resources, including schools. The location of a school in southern Kandahar province, for instance, set off a long-running dispute between two tribes vying for government assistance. When one tribe attacked the school built on territory of the other tribe, it reflected local grievances as well as opposition to the government’s policies in that region.110

In other areas, schools are attacked not as symbols of government, but rather because they provide modern (that is, not solely religious) education, especially for girls and women.

In a March 25, 2006 statement issued by the self-styled spokesperson of the Taliban Leadership Council, Mohammed Hanif, the Taliban explicitly threatened to attack schools because of their curriculum:

In general, the present academic curriculum is influenced by the puppet administration and foreign invaders. The government has given teachers in primary and middle schools the task to openly deliver political lectures against the resistance put up by those who seek independence. . . . The use of the curriculum as a mouthpiece of the state will provoke the people against it. If schools are turned into centers of violence, the government is to blame for it.111

The statement went on to target girls’ education directly: “Another matter worth pointing out is that failure to observe the Islamic veil at girls' schools, co-education and visits by the American forces to schools are not acceptable to any Afghan. Therefore, we are strongly opposed to it and cannot tolerate it.”112 Around the same time, however, Hanif told a journalist: “We have not threatened anybody except those who work for Christians and for foreigners in Afghanistan. . . . We have never killed any teacher or any student.”113 In fact, Human Rights Watch has documented many instances, set out in detail below, when Taliban attacks were directed at girls’ schools exclusively, or explicitly targeted teachers and schools providing education to girls.

Similarly, on April 27, 2006, anti-government warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar reportedly issued a press statement vowing to continue jihad against foreign forces and stating that “now the infidel forces had been forming education system and syllabus for Afghans to divert our youth from Islam to Christianity.”114

The rest of this section surveys cases of attacks on teachers, students, and school buildings in several provinces from 2004 to 2006 and the use of so-called night letters to terrorize teachers, students, and parents. It also discusses the impact of crime and impunity on education.

Attacks by Taliban and Warlords on Education in Southern and Southeastern Afghanistan

The following case studies document attacks on schools in eight provinces in south and southeastern Afghanistan. These are the areas where there have been the greatest of attacks on teachers, students, and schools. Notably absent are the provinces of Uruzgan and Paktika, which have high levels of insecurity and low levels of development, but where insecurity has made it extremely difficult to get accurate information.

Kandahar City and Province

Kandahar city and its eponymous province comprise the second most important area in the country after Kabul. The city is the economic, political, religious, and cultural center of the Pashtun belt in the south and was the de facto capital of the Taliban while they were in government. Since the Taliban’s overthrow, the international community, led by the United States has maintained a significant military presence there and made efforts to develop the area’s economy (since late 2005, Canadian forces have taken the lead in providing security for Kandahar). Nevertheless, increasing insecurity has significantly constrained much of the development work, limiting it by and large to the city limits.

A representative on the Kandahar provincial council provided her impression of the impact of rising insecurity on education, particularly for girls, in Kandahar in December 2005:

The security situation was fine, but during the last two years it is growing worse day by day. In the first three years there were a lot of girl students—everyone wanted to send their daughters to school. For example, in Argandob district [a conservative area], girls were ready, women teachers were ready. But when two or three schools were burned, then nobody wanted to send their girls to school after that.115

In 2004-2005, 19 percent of officially enrolled students in Kandahar province were girls.116 Outside of the city, however, only 10 percent of enrolled students were girls, and no girls were enrolled in four of Kandahar’s fifteen educational districts.117 According to USAID, two hundred schools in Kandahar were closed for security reasons by early 2006.118

Girls’ schools in Kandahar city, in the past relatively secure, came under attack in 2006. ANSO, U.N. sources, and the press reported the following attacks in the city at the end of 2005 and in 2006:

- December 27, 2005: a hand grenade was thrown at Mirwais Mina girls’ school in district 7. The school was empty at the time, but the windows were blown out and the walls, roof, and doors damaged. A suspect was arrested in February 2006.119

- January 7, 2006: unidentified men tied up two school guards and set fire to a co-educational primary school in Loya Wiyala village just outside Kandahar city.120 The attack followed threatening letters, according to provincial deputy police chief Colonel Abdul Hakim Angar.121

- January 8, 2006: men set on fire Qabial co-educational primary school in Kandahar city, after locking three janitors inside.122 The men were rescued. According to provincial deputy education director Hayatollah Rafiqi, on the same day more than a dozen armed men also set fire to classrooms and school documents at Zeray primary school in Kandahar province.123 As a result, female students were unable to take exams.124

- Early March 2006: a homemade bomb was left next to the house of a teacher at Zargona Girls’ High School in Kandahar city.125

- April 18, 2006: night letters warning women and girls not to attend schools and offices were found in district 10.126

Human Rights Watch interviewed a number of education officials from rural districts in Kandahar who described attacks on schools in their areas.

Maruf District, Kandahar

In 2004, the Taliban aggressively campaigned to close the schools in Maruf district, Kandahar, a partially mountainous area on the border with Pakistan. According to an education official from the area, in 2003 “all the people of the community contributed and helped the schools . . . . People were sending kids to school. Then the people who had been through the difficulty of migration were very happy to send their children—girls and boys.”127 But the following year, he explained, the Taliban began to threaten and beat teachers, and shot a principal (mudir). They also threatened a school full of children. Around the same time, several schools were burned or blown up. The Taliban went from village to village, calling meetings at the mosque and ordering all schools to be closed. They were successful: all forty schools in the district closed in 2004 and did not open again in the 2005-2006 school year.128

In June 2004, around three hundred students were attending Sheikh Zai Middle School, located on the outskirts of a community in the mountains of Maruf district.129 Girls attended grades one through four; boys went until class six. There were ten registered teachers but only six were present on the day the Taliban came in June 2004. That morning, a person came to the school and warned the head teacher that the Taliban were coming. The head teacher got on his motorbike and went to the district center to inform the authorities. In the meantime, members of the Taliban arrived at the school. According to a man from the district who spoke with the teachers and some of the students shortly thereafter, the Taliban “went to each class, took out their long knives . . . locked the children in two rooms [where the children] were severely beaten with sticks and asked, ‘will you come to school now?’”

The six teachers later told residents what happened to them. According to a resident, the teachers told him that:

They were taken out of school, their eyes were tied, they were continually hit, and they were taken to the nearby mountains on foot. . . All six were separated and nobody knew where the other was. One by one the teachers were asked why they didn’t obey what had been announced on radios and in the mosque. They said they hadn’t heard about it and the only thing they wanted was to educate children. The Taliban asked them individually, “Why are you working for Mr. Bush and Karzai?” They said, “We are educating our children with books—we know nothing about Bush or Karzai, we are just educating our children.” After that they were cruelly beaten and let go. . . .

The teachers were so cruelly beaten that until now they are handicapped. One of them had his leg broken and he can’t walk and can’t work. One of the others still has problems with his hand and can’t use it.130

In the meantime, the head teacher returned home. The same Maruf resident, who spoke with the head teacher three days later, described what the head teacher said happened that night:

About 7 or 8 p.m., when people started eating dinner, the Taliban came to his house. They knocked on his door and when he came out, they abused him and grabbed him and pushed him, saying, “How many times have we informed you to close your school?” The headmaster said that he hadn’t heard anything about that. They hit him with a gun butt on his head. The children started crying. The people from the nearby houses came out. One of the Taliban made a burst with his Kalashnikov [assault rifle], and some of the bullets hit the head teacher in the upper thigh. He fell to the ground. The people took him to the local doctor. He had two bullet wounds, and the doctor said it was dangerous and he should go to Quetta [Pakistan] or he would die. His bones were broken, and they didn’t join connected and now they overlap.

The head teacher and his family resettled outside of the district because they were afraid to return.131

Around the same time, the Taliban also went to another co-educational primary school in Samai village, in the same part of Maruf district. According to an eyewitness, in the mid-morningmen armed with Kalashnikovs, rocket propelled grenades, and other weapons encircled the school and began “kicking and breaking the doors.”132 Then the eyewitness, who was hiding outside, saw them enter the school. After about an hour, he said, he saw the students—girls and boys—running away. The teachers remained and later told the witness that “the Taliban told them to ‘[s]top educating people because you shouldn’t follow the foreigners, and whoever told you to give this education is naughty, and you should not continue the work. . . . This time we are leaving you, but the next time you will be killed.’” The teachers also said that the Taliban “took the books and papers and tore them apart and broke the windows and doors of the school.” After that, the witness said, “everyone was afraid for his life, so we all decided not to go to the school and the school was closed.”133

In the same period, three other schools in the district were destroyed: two primary schools and a middle school.A man who saw two of the schools afterwards described them as follows: “The roofs were made of wood and were set on fire. Some of the mud walls were broken and gone.”134 At the middle school, he said, “the roof was down, the windows gone, just the ruins were there.”

All schools in the district closed after these incidents. Then in late July or early August 2004, the Taliban came to a mosque in the district, made announcements against the government and against education, and threatened a school headmaster. “After the evening prayers,” an eyewitness said:

[S]ome Taliban stood up and made an announcement. They had a full printed document signed by their commanders: Mullah Daudullah and Mullah Akhtar Mohammed . . . At the top it was printed: “the students of Islam [a translation of Taliban].” The rest was all handwritten. The subject I saw was a notice to all the Ministers of Afghanistan. First they explained the needs of jihad and the benefits of jihad that you get from God if you do it. They noted that the Americans had come to Afghanistan again so you should fight against them as you did the Soviets. If you cannot do jihad, don’t send your children to the army. Close the schools. Don’t have any relations with the government. There were some other points I don’t remember. After that they said that if anyone was found guilty of doing those things, he will be killed.135

After they made the announcement, some of the Taliban individually threatened a headmaster of a primary school to keep the school closed.136

The teacher from Maruf concluded his description of recent events: “During jihad I was a student, now I am a teacher here. I have seen war for thirty years. Everything is destroyed.”

Ghorak District, Kandahar

Schools in Ghorak district of Kandahar, on the border of Helmand and Uruzgan, have been under attack at least since 2003. According to an education official from the district, six schools in the district were closed and three were open, all for boys.137 The official listed the status of the following schools in December 2005:

- Bahram Middle School—open with one thousand students, twelve teachers

- Zurkhabad Primary School—closed for the past three years

- Azim Khan Primary School—closed for the past three years

- Kai Kuk Primary School—open with one hundred students, six teachers

- Hassan Abad Primary School—open with eighty to ninety students, six teachers

- Weshtal Primary School—closed for the past one and a half years

- Gul Khani Primary School—closed for the past three years

- Bai Kush Primary School—closed for the past three years because of night letters

- Afghana non-registered girls’ school—closed for the past three years after two people were killed. “The teacher was afraid, everyone was afraid, and the girls’ school was closed.”

When Human Rights Watch asked why the schools closed three years before did not re-open, the official answered, “there is no security and security is even worse now. . . . Don’t even talk about girls—there aren’t even any boys in school! There are no teachers!”138 When we asked if the three open schools would remain so, the official responded: “I would say that either they will be closed today or tomorrow. There is no future there. The students are afraid, but even these are the students who live very close to the school—otherwise, no one is coming.”

In late 2002 or early 2003, teachers and education officials in that district received threatening letters. Then Zurkhabad Primary School, a tent school, was burned down in the middle of the night, and the two guards sleeping inside were severely burned. According to the local official, the community reported the night letters and the school burning to government officials under district chief Mohammed Isa Khan but no investigation was conducted. The following year, another primary school made of mud and brick was burned. The district chief’s commander of security arrested three teachers on the allegation that they were responsible.

When we asked who burned these schools, the official said he did not know. “Either the Taliban or others who are against the government,” he said. “Nobody knows where they come from. They only come at night and not in the centers. From far away regions they come, but nobody recognizes them.”

Sometime in late 2004, education officials in the district received more night letters, which they forwarded to the head of the provincial education department. Shortly thereafter, armed men, whom the official described as “anti-government elements,” targeted the official.He described what happened:

After the letters, they came to my house in my village. The [armed men] surrounded the village. I was not there at the time. The village helped save me. I didn’t go to the mosque as usual because I had work. These people surrounded the mosque and moved through the streets looking for me. People came out and they left. I was the only guy in the village involved with the government or with education. They asked my father and my relatives where I was, and they announced that if there was anyone present in the village who was in the government, the people should bring them out because if they find them later, then nobody can complain about what they would do.

The official fled with his family to another city, leaving his house and land behind. However, he remained officially in his job.

Then, around mid-2005, in his own village, his office in the Kai Kuk school was burned at night. Upon hearing the news, he said, he went immediately there and saw that the lock on the door was broken and a table and chair were burned. “Some of the things they took away and the rest they burned,” he explained. “They took away registration forms, examination papers were missing. We looked through the burned pages, but we didn’t find these documents. The registration papers had the names of the students on them, not just for this school but for other schools as well, because this was the district office.” Many students stopped coming to the school after that. “We went to those students who aren’t coming now but who came before and they said, ‘What can we learn? And we will even lose our lives.’ It’s because of the insecurity now. When there are enemies moving all around you, what can you learn?”

Afterwards, night letters were found in the mosque informing people not to help the government or send children to the army. By late 2005, the official said, the threats had driven all district officials from the district.139

Khakrez District, Kandahar

According to a head teacher from Khakrez district, there are ten official boys’ schools in the district, dating back many years.140 Although the schools closed during “the first period of the mujahedin,” they were open under the Taliban, albeit with different curricula. There are no schools for girls, the head teacher said, because “there is no security for girls.”141 In 2005, at least four schools were closed, three following attacks. (The fourth closed because there were no teachers, he said.) Although there are 1,900 students in the district, “now less than half are in school because parents are afraid. In the first week [after the last attack], no students came. Now there are more because the district chief came and ordered them to attend school.”142

In May or June 2005, opposition groups closed three schools in the cold weather areas of the district: Chenar Manukheil, Tambil, and Khaja Alam. According to the head teacher:

The anti-government elements attacked two on one day, and then Khaja Alam a day later. These are not school buildings, but open air schools under trees. The equipment, the carpets were looted. They held the teachers for one day, roughed them up a bit, threatened them, then released them. . . . They’ve stopped teaching because there’s no school now, but they’re still there in the areas.143

Then in September or October 2005, a written threat was posted on the school door of Lycee Shah Maghsood Alaye Rahman. “You are helping the U.S.,” it read. “Stop it, stop this work. If you are hurt, don’t complain.”144

On the night of November 12, 2005, the head teacher’s office in this school was burned, and the teachers received threatening notes. The police investigated and concluded that four people were responsible, the head teacher explained. The police followed their tracks to the mosque and found them there; two of the men, he said, were jailed.145

Panjwai and Dand Districts, Kandahar

Panjwai district is just west of Kandahar city. Yet it is a world apart, a place where attacks by opposition groups have effectively stopped most development work.146 Teachers and schools have borne the brunt of the insurgents’ campaign of intimidation, which has included murders of teachers, attacks on schools, and dissemination of night letters.

HayatullahRafiqi, director of the provincial department of education, told Human Rights Watch that a Panjwai teacher, Abdul Ali, was killed by insurgents around October 2005. “It really affected all the teachers, and the schools closed down,” he told Human Rights Watch. Furthermore, at least thirteen teachers were threatened by name, several by night letters.147 “How can we expect schools to open?” Rafiqi asked.

The attacks also shut down most development work in the district. A major Afghan NGO, Co-Ordination for Humanitarian Aid (CHA), which was heavily involved in education projects in the district, told Human Rights Watch that it stopped its operations there (accelerated learning classes for older girls who had fallen behind during the Taliban’s rule) after Abdullahi’s murder, and after insurgent groups threatened CHA’s staff as well as parents of students. “They warned the parents that if you let the children go to classes, they will kidnap and kill them or bomb the classes so we couldn’t continue,” an education official with CHA said.148

In October or November, Kwaja Hamad Maimandi co-educational primary school in Serwan village was set on fire, a day after the National Solidarity Program opened. The school re-opened in February 2006.149

The attacks on Panjwai were severe enough that opposition groups used them to intimidate people in other districts. The CHA official said that night letters in another district of Kandahar province warned against accelerated learning classes by invoking Panjwai: “If you go to classes you will face the problems of Panjwai,” the night letters said. Schools in Dand, between Panjwai and Kandahar, also suffered because of the violence in Panjwai. As the head teacher of Dand explained, “The schools close to Panjwai are anxious, but the others are okay. The teachers at these schools are there, but they are intimidated. The parents are very afraid too.”150

Dand itself has witnessed attacks on school personnel. According to the head teacher from the area, in early October 2005 the thirty-one-year-old custodian of the Haji Jom’eh middle school in Belandai village, Sultan Mohammad (also known as Bodo), son of Haji Mohammad, was bringing dinner from home when insurgents, whom locals identified as Taliban, abducted him. “The Talibs took him from the village to a nearby grove of cypress trees. They hanged him with his turban, then they tossed his body into the irrigation canal.”151

The next day, the teacher said, “People didn’t see him [Bodo] in school. They looked around and found his body in the canal. . . . The day after, we found a threatening letter in the Ministry of Education office. It said to the teachers ‘if you go to school, this is what will happen to you.’” After that, “all teachers have been hiding. . . . All the schools in the district closed, because teachers said we will only work after an investigation. There has been no investigation yet.” While the middle school remained closed, the other twenty-seven schools re-opened, but many students did not return, he said. “The four schools closest to Haji Jom’eh are heavily affected by the incident. For example, at one, out of 130 students, only forty students attend school, at another only twenty-five of 120 students go.”152

The head teacher of Dand ended his interview with Human Rights Watch by confessing that he had also been targeted by opposition groups the previous week. “There was a night letter specifically naming me too. I was returning from prayers, there was a notice posted. It said “if you keep teaching, you know what will happen.” So I went to the elders and they said that anyone who harms me is doing a bad thing. But as of two nights ago, I’ve fled the village because the elders said if we lose you, the whole village will mourn. We don’t have anyone like you, so leave the village, vary your routine, just do your business and leave, stay in the city.”153

On January 20, 2006, Sufi village school in Dand district was set on fire, according to a report received by ANSO.154On February 4 and 5, hand grenades were left at a school in Panjwai that was under construction, and arson was attempted at Kawaka Mayweed school in Spirant village but stopped by school guards.155 On May 19, 2006, a school was reportedly burned down in Chaplani Village in Dand.156

Shageh, Kandahar Province

Insurgent attacks on schools have effectively ended what little government representation there was in several areas of Kandahar province—a fact to which regional school officials explicitly attested. Shageh’s head teacher explained:

There are nine schools in the district, one middle school [grades one to nine], the rest are primary. In half of the district, schools don’t function because the Taliban are very strong and there is no security. In the areas under Karzai’s control, there are nine schools.

One teacher, Ramazan, was killed in [June 2004]. He was warned several times orally, and then he was shot in the foot. Later, during the school holiday, he left his house in the afternoon and was found shot. No one saw what happened. Of course if we find out who shot him we will attack them.

One month ago [an Afghan NGO] built a school, but there are no students there because of security. Parents say if we send students they will face Mullah Omar and Gulbuddin Hekmatyar.

They [opposition groups] have threatened me, said “you’re getting paid by the U.S. and we will kill you.” About five months ago I received an oral warning like that. The three women teachers were also threatened about five months ago. They were told not to cooperate with the U.S., but they still teach.157

* * *

In addition to the above incidents, ANSO and U.N. sources report the following incidents in other districts in Kandahar province in 2006:

- January 18: an anti-tank mine was found buried on the main route leading to a school in Shorandam village in Daman District. An Afghan National Police team was informed and disposed of the device.158

- February 3: night letters threatening students and teachers were left at Ghazi Mohammed Ayb School in Maywand district, and a school was set on fire in Ashuka, Zherai district.159 According to U.N. sources, as of October 2005 schools in these two districts and in Arghistan district were closed due to activities of armed opposition groups.160

- April 21: an explosion, believed to be the result of a device buried there earlier, destroyed a boundary wall at Haji Kabir school in Zarre Dasht district.161

- April 22: an improvised explosive device was detonated inside Haji Malim School in Spin Boldak district, and local security forces recovered and defused another device in the same school in the area. No casualties were reported.162

|

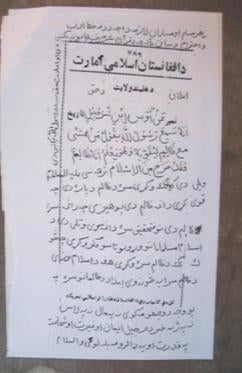

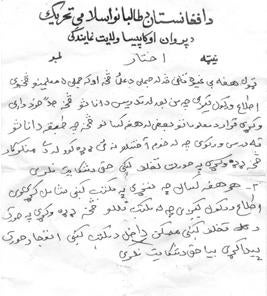

Taliban Night Letter from Helmand

This is an obligation on every Muslim to respect this letter because there are verses of the Koran versus in it and because there are Allah’s Messengers’ words in it.

In the Name of God Afghanistan Islamic Emirate Helmand Province Righteous Statement [Arabic verse from the Koran] Translation: God’s Messenger (Peace be Upon Him) has said: He who launches a joint attack with the despicable and the vicious, or he who support the vicious, should know that he is a vicious person and indeed, he has withdrawn from Islam. Muslim Brothers: Understand that the person who helps launch an attack with infidels is no longer a member of Muslim community. Therefore, punishment of those who cooperate with infidels is the same as the [punishment of] infidels themselves. You should not cooperate in any way -- neither with words, nor with money nor with your efforts. Watch out not to exchange your honor and courage for power and dollar. Wa-Al Salaam |

Helmand Province

Helmand province is one of the least secure areas of Afghanistan. The province borders Pakistan and is quite close to the Iranian border to the west; it has witnessed clashes between Taliban and coalition forces on a daily basis. Helmand is also one of the centers of poppy cultivation and heroin production in the country. As a result, development in the province has nearly ground to a halt, and schools and teachers are by and large unable to operate in most areas of the province. The difficulty of operating in Helmand allows us to present only a part of the picture there. The United Kingdom has recently assumed responsibility for securing Helmand, and has dispatched a force of some 3,300 troops there.163

All together, according to the director of education for Helmand province, eighteen schools in the province had been burned down and a total of 165 schools had closed because of threats as of January 2006.164 Even before the series of attacks on schools and teachers described below, only 6 percent of students in Helmand were girls in 2004-2005, and no girls were enrolled in school in nine of Helmand’s sixteen educational districts.165

On December 14, 2005, in Zarghon village in Nad Ali district, two men on a motorbike shot and killed a teacher in front of his students. An eyewitness told Human Rights Watch that around 10:30 in the morning, thirty-eight-year-old Arif Laghmani was shot at the gate of the boys’ school where he taught. “I saw these two men,” he told Human Rights Watch. “One of them fired a full magazine in Laghmani’s chest. . . . I was afraid for my life and hid around a corner. I did not know who the victim was. After the killers fled, I went to the gate and saw Laghmani laying dead. . . . It was awful. . . . We have been receiving night letters, but no one thought they would really kill a teacher!”166 According to press reports, the night letters commanded Laghmani to stop teaching boys and girls in the same classroom.167

Four days later in Lashkargah city, the provincial capital, at around 11:00 in the morning, two men on a motorbike opened fire around Kart-e Laghanschool, killing a student and the gatekeeper.168 The police chief of Lashkargah, Lt. Gen. Abdul Rahman Sabir,told Human Rights Watch that the men “shot indiscriminately,” hitting ninth-grade student Gulam Rassol in the chest, and the school’s gatekeeper, Salahudin (son of Abdul Ghaffor), a thirty-five-year-old father of five, in the stomach.169 Two other students were also injured by bullets, he said.170

The press and government officials blamed the attacks on “anti-government elements” or more specifically, the Taliban. However, Helmand is also a hotbed of criminal activity, where locally powerful criminal figures (some of them even allegedly in government positions) have an interest in disrupting government control and threatening the activity of international forces.

Human Rights Watch received information about five other killings of teachers and education department officials around the same time. The victims were:

- Habibullah, son of Yar Mohammed, head teacher in Qala-e Gaz, Grishk district;

- Mohammed Zahir, son of Habibullah, teacher in Qala-e Gaz, Grishk district;

- Lal Mohammed, son of Khoodai Raheem, deputy head of the education department of Washer district;

- Moolah Daad, son of Sardar Mohammed, an education department investigation officer of Naw Zad district; and

- Allah Noor, son of Najibullah, an education department investigation officer of Kajaki district.171

The attacks on education continued in 2006. According to ANSO, U.N. sources, and press reports:

- January: fires were set at a school in Tornera located in Grishk district; at a school in Nahri Sarraj district; at Shakhzai Middle School in Mawzad district; at Koshti school in Garmser; and at Shapshuta Middle School in Washer district.172

- On or about January 28: three schools in the villages of Mangalzai, Hazarhash, and Sarkh Dozin Nawa district were set on fire.173 According to news reports, desks, chairs, and books were burned in two of the schools, which were boys’ schools; the third was coeducational and consisted of large tents which were completely destroyed.174

- January 29: a boys’ primary or middle school in Malgir Baizo, Grishk, was set on fire and furniture and stationery destroyed.175

- February 7: unidentified gunmen set a boys’ middle school on fire in Loymanda, Nad Ali district, but residents were able to put it out.176

- On or about February 20: the boys’ high school in Zarghan village where Laghmani was shot in December was set on fire.177 Haji Mohammad Qasim, head of Helmand's educational department, told journalists, “All the books, desks and chairs have been burnt, but no one was killed or injured in the incident.” Around 1,200 boys were enrolled at the school, he said, but the school had been “sealed” after Laghmani was shot. Afghan officials blamed the Taliban, but Qari Yousef Ahmadi, a self-declared spokesman for the Taliban, denied Taliban involvement.178

- April 1: men attempted to burn a school in Sayed Abad Village, Nad Ali District. Villagers intervened and, although they came under small arms fire, “successfully drove off the arsonists and saved the school.”179

- April 4: a school and the home of an administrator were set on fire in Baghran district.180

- On or about May 30: gunmen in four vehicles set fire to a middle school in Group Shash, Nad Ali district, and left handwritten pamphlets on the gates of other schools warning teachers not to come to school. The provincial governor’s spokesperson blamed the “enemies of the country” (a term used by Afghan officials to refer to Taliban), but self-described Taliban spokesman Qari Yousaf Ahmadi expressed ignorance about the incident and told journalists that burning schools was not Taliban policy.181

|

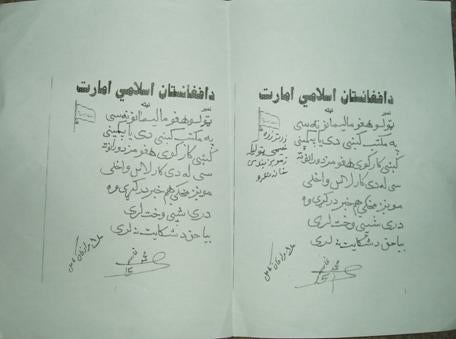

Taliban Night Letters from Zabul

Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan This is to warn all the teachers and those employees who work with Companies to stop working with them. We have warned you earlier and this time we give you a three days ultimatum to stop working. If you do not stop, you are to blame yourself. Mullah MuradKhan Kamil |

Zabul Province

Zabul province has been a hotbed of insurgency since the fall of the Taliban and subject to tremendous insecurity, some of it associated with the cross-border narcotics trade. With the assistance of U.S. forces, security improved last year in the provincial capital and along the Kabul-Kandahar highway. However, Zabul remains one of the most dangerous and least developed areas of Afghanistan. As in Helmand, the obstacles to Human Rights Watch and other NGOs operating in the province allow us to present only a partial picture of insecurity there.

Only 9 percent of Zabul’s students were girls in 2004-2005, and four districts in the province had no girls enrolled at all in school that year.182 In March 2006, a provincial education department official gave Human Rights Watch similar figures: only 3,000 (8 percent) of the 37,743 officially enrolled students in Zabul were girls.183 Due to insecurity, he said, only ninety-five of the provinces 181 schools were open.184

Zabul was the scene of one of the more gruesome attacks on a school official in Afghanistan—the decapitation of a headmaster on the night of January 3, 2005. The brutality of the attack shocked even battle-hardened Afghans and sent ripples through the community of teachers and development aid workers.185 According to provincial education department director Mohammad Nabi Khushal, four “[a]rmed militants entered the house of the headmaster . . . and brutally beheaded him in front of his children.”186 The victim, Abdul Habib, reportedly worked at the Sheik Mathi Baba School, one of Zabul’s two high schools, both located in the provincial capital, Qalat.187 Director Khushal told journalists that insurgents had occasionally put up posters around the city demanding that schools for girls be closed and threatening to kill teachers.188

General insecurity has also had an effect on education. Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission researchers found in 2005 that: “In Qalat district of Zabul province interviewees reported that they do not send their children to school because of security fears (kidnapping and threats from armed men) and because the children have to work.”189 The Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission’s report highlights that in Zabul, like in other areas across southern Afghanistan, it is difficult to distinguish between insurgent activity and the action of criminals, because in some cases the two groups share a common purpose in weakening the government, or even work directly to support one another.

In 2006, the following threats and attacks were reported:

- On or about January 12: threatening letters were distributed in schools in Naw Bahar, Argandab, and Daychopan districts directed at teachers and students and ordering the schools to close.190

- February 8: a boys’ high school in Qalat city was burned during protests against cartoons printed in a Danish newspaper that were widely believed to be derogatory to the Prophet Mohammed.191

- April 6: a school in Khomchina village, Mizan District was set on fire.192

|

Taliban Night Letters From Ghazni

Greetings toward the respected director [of education] of Ghazni province, Fatima Moshtaq. I have one request, that you step aside from your duties. Otherwise, if you don't resign your position and continue your work, something will happen that will transform your family and you to grief. I am telling you this as a brother, that I consider you a godless person. I am telling you to leave your post and if you continue your work, I will do something that doesn't have a good ending. It should not be left unsaid that one day in the Jan Malika school I heard Wali Sahib praise Ahmad Shah Masood, I wanted transform your life to death and with much regret Wali Assadullah was present there and I didn't do anything to cause your death. But if you don't resign your work, I will attack you and take you to death. With respects, 27 Meezan 1384 At the bottom (last paragraph): Look dear Fatima consider your poor employee who will suffer. He was in front of the house look at how many body guards you have for instance the one who was there but if you have them it doesn't matter to us. I was following you from 4 in the afternoon till 7 at night. With Respects. |

Ghazni Province

The historic city of Ghazni, about four hours drive south of Kabul, was the center of an empire covering much of northern India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and eastern Iran in the eleventh century. Today it is capital of one of Afghanistan’s more volatile provinces. The international community largely suspended operations there in May 2003, when a French UNHCR employee was killed in Ghazni city. The city itself is relatively calm, but much of the province is beset by opposition groups, including the Taliban, those associated with Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, and local criminal gangs. Broadly speaking, areas south of the ring road are considered seriously unsafe, while northern areas are calmer.193

Local education officials blame the Taliban for some of the attacks on education in Ghazni. One official from Gilan province, one of the least secure in Ghazni province, said: “Some Talibs are from the community and some are coming from Zabul. Those coming from Zabul taunt our Taliban and say, ‘If there are no schools running in Zabul,… how come the schools are running in Gilan?’”194

In other cases, evidence indicates criminal responsibility; for instance, a particularly brutal attack during which killed two education officials in early December 2005 was blamed on robbers, because the officials were robbed of the payrolls they were carrying, contrary to the usual practice of the ideologically motivated groups.195

Overall, in 2004-2005, 31 percent of students officially enrolled in school in Ghazni were girls. But enrollment was much higher in districts north of the ring road than those south of it. The two districts (out of eighteen) with no girls enrolled were in southern Ghazni.196

A teacher from troubled Gilan district, south of Ghazni city, described his school: “We have two shifts, one from first to sixth grade, one from seventh to twelfth in the evening. There are about five to six hundred students. There are eighteen teachers, forty students in one class.” The school has frequently faced security problems, he told us. “Last year in April [2005] our school was closed by the Taliban for two months, they threatened us and told us this school must be closed. Night letters are regularly sent.”197

A teacher from Deh Yek district told Human Rights Watch that in his district girls’ education, while only offered from grades one to three, was the focus of attacks:

The boys’ schools have not been threatened, they haven’t had problems; the focus has been on girls’ education and on television and people with antennas. The attacks are meant to make sure that there are no girls’ schools next year. The teachers want greater pay in order to face the threats. Even some of the elders now say ‘get rid of the girls’ school, we’ll built a clinic instead.’198

An official in the provincial education department described problems in Andar district:

There are a lot of problems in Andar—the biggest is the security problem. The teachers are threatened and told not to go to school. . . . At the moment there is no school for girls in Andar though we are trying for it. . .

A lot of night letters have been sent to teachers and students, even to the mosques. The teachers, headmasters, and modirs [principals] were and are threatened continuously. The police and ANA [Afghan National Army] are very weak—they are not in a position to bring any security or peace. Usually the night letters are signed by Jaish al-Muslemin or Taliban. No schools have been burned in Andar, but three schools were burned in Giro in May this year. . . .

In Hale Khojiri school, some teachers were threatened and told if they continued to go to school, their blood would be on their own hands.199

In addition, the official said that he had been personally threatened.

In the first half of 2006, the following attacks were reported by ANSO, the United Nations, and the press:

- On or about January 16: “anti-government elements” burned three tents at Mateen Shahid School in Dihyak district.200

- February 13 or 14: a school in Agho Jan village, in southern Gilan district, was set on fire. There were mixed reports about the damage, ranging from several rooms being saved to the building being completely gutted.201

- April 16: a secondary school in Muqur district was set on fire and around two hundred books, including Qurans, were burned.202 The attacker fled in a Toyota Corolla, ANSO reported.203 According to the United Nations, a school in the same district was destroyed on April 30.204

- May 28: “a group of unknown men” set fire to a school in the Khogianai area of Jaghatu District in the night.205

Paktia Province

Paktia’s provincial capital, Gardez, was the location of the first PRT established in Afghanistan. The province, nevertheless, continues to suffer from serious violence and insecurity, with little sign of a turnaround. A western resident of Gardez said bluntly: “We’re in the middle of an insurgency here. [Over the past two years] I’ve seen a massive decline in security here.”206 In Paktia, the insurgency, broadly referred to as the Taliban, combines groups opposed to the central government, tribes determined to preserve their freedom of action, and criminal networks whose profits may be supporting the opposition groups and tribes and who in turn may collaborate with these groups.

In 2004-2005, 24 percent of students officially enrolled in school were girls; in two of Paktia’s fourteen educational districts no girls were enrolled in government schools at all.207 One of those districts is the restive Zurmat region, where two Afghan employees of the German NGO Malteser were killed by insurgents, allegedly the Taliban, in August 2004. The murders led to a drastic reduction in NGO activity in the entire province, although a few continue to operate in the relative safety of Gardez and neighboring areas. Aid workers brave enough to continue their work do so at great risk. One Western aid worker told us: “Our staff in Zurmat received night letters, about two weeks ago, specifically naming them.”208

A tribal elder from Zurmat described the situation thus: “At night, the government is the Taliban. They rule by their night letters.”209

In October 2005, Taliban forces shot and killed two men at a mosque in Zurmat, according to the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission. The two were a school custodian and another person, Raz Gul (son of Abdul Gul), and Mohammed Wali (son of Wali Mohammed).210 The gunmen took two others but later released them.

Education has nearly halted in the area. The tribal elder told us: “There are three lycees in Zurmat but none for girls. The conditions don’t exist, because of the government of the night. Some teachers have been threatened, for instance [name withheld], a teacher at Lycee of Sahrak school.” 211

The Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission also described an attack on a school in Zurmat in August or September 2005, and “another attack by a bomb in front of a school. It injured several students, but the Taliban denied involvement.”212 The denial was noteworthy because the Taliban do not always explicitly deny (or acknowledge) their involvement in attacks.

In the first half of 2006, the following attacks were reported by ANSO and U.N. sources:

- April 20: at around 5 p.m. in Dowlat Khan village, Zurmat district, an improvised explosive device consisting of an anti-tank mine and a remote control device was detonated near a school.213

- April 29: an attack on a local government office in Laja Manjaalso resulted in damage to a school.214

Logar Province

Logar, just south of Kabul, is a relatively well-to-do agricultural province. Nevertheless, the area has witnessed an ongoing campaign against schooling, particularly for girls.215 Even before the recent wave of attacks, in 2004-2005, only 31 percent of students enrolled in school were girls, and in one of Logar’s eight educational districts no girls were enrolled in school at all.216 Both the Taliban and the forces of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar’s Hezb-e Islami are reportedly active in Logar, and both have an interest in challenging the central government’s writ in this previously relatively quiet area.

In the first half of 2006, ANSO and the United Nations reported the following incidents:

- April 18: rockets struck Kochi school in Puli Alam district.217

- May 2: during the night, unknown men set alight a madrassa (religious school) where boys studied in Pul-i Jala, Khawar district.218

- May 9: unknown individuals set on fire Qala-e Now Shahr high school in Charkh district at around 4 a.m. Police subsequently found a hand grenade attached to a mortar with wires in a bag inside the school. (Authorities in Logar province could not confirm the report).219

- May 12: night letters were distributed in Azra district asking people to stop working with the government and cooperating with foreigners, and stating that girls should not attend schools because it is disrespectful of Islamic and Afghani tradition and culture.220

Charkh District, Logar

Residents of Charkh district told Human Rights Watch about attacks on both boys’ and girls’ schools in 2004 and 2005.

Around September 2004, a mine was exploded at night in a girls’ school in Qala-e Now. A teacher from the area described what happened:

It was during the night. . . . I was sleeping and I was woken up by the sound. We went out and saw the building of the girls’ school was destroyed, the roof came down, the door was burned. . . . There were a lot of flames and smoke. I was a little bit scared when I saw that!

It might have been a remote-control mine. Everyone was saying that, and we found pieces of the mine. I saw them myself. It was a piece of steel. It was not too far away because there were walls surrounding the building. It hit the wall and fell to the ground.221

The next day, he said, they moved the school to a private home.

For one week after that just a few girls came and then we encouraged them to come. But there were some who never came back at all—maybe 10 percent. . . . I have a girl relative who went to that school. Although we were worried about her, we didn’t forbid her to go because it’s her future, but I still feel worried. I feel there is a security problem. But now we are watchmen—we made a schedule and each person has one night. . . .We guard both the girls’ and the boys’ school.222

Now, he said, the girls’ school “is not very accessible because of mines. Before we didn’t have a girls’ school. Now it’s difficult—sometimes there are rockets, mines, [threatening] flyers distributed. . . . And it is a little bit far away. Most years we have four to five security incidents at this school.”223

Although not physically attacked, the teachers and students of Modana boys’ high school in Mulanachuk were threatened with night letters in April or May 2004 and again in May or June 2005. According to a teacher at the school, the first time it happened, letters were left on the doors of the school, the walls, and the trees. The letter, he said, read: “If you come to the school it will be dangerous for you. . . . If you continue being a teacher, you shouldn’t complain to us. Stop your teaching or otherwise you shouldn’t complain to us if something happens to you.” He said the letters were “written like a warning, that they might attack or kill us. These weren’t the specific words but this is what I thought they meant. Of course we were worried because it was a strong warning because we thought they would attack us. But we didn’t stop teaching.”

When the teachers found the letters the next morning, they tore them down, but not soon enough to keep the students from finding them, he told us. “They were spread around widely. We even collected copies from the students. The students were discussing among themselves that the teachers and the school would be attacked, but we said, ‘don’t worry, they don’t have the power.’” The teacher never found out who left the letters, which were unsigned, but he noted that they “were typed in Dari and Pashto.”

In May or June 2005, letters were left again. The teacher could not remember the exact words of the second letter, he said, “but the message was the same: teachers don’t go to school.”224

Around the beginning of December 2005, rockets were fired in the district, destroying a government office and landing near the boys’ school.225

Baraki Barak District, Logar

A local education official from Baraki Barak district told Human Rights Watch of an attack on a girls’ school in Padkhwad-e Roghani village around June 22, 2005.226 According to the official, insurgents associated with the Taliban and with Hekmatyar’s Hezb-e Islami faction operate in the area, and people are afraid of them. Around 650 girls attended the school, studying in grades one through four. The school was located in tents placed within the surrounding walls of a private home; however, some people in the village felt the location was too close to one of the two boys’ high schools in the village.

The official visited the site the day after the attack and described what he learned. At around midnight:

A group of armed men tied both school guards with a strong rope and then beat them very badly. They also brought some petrol with them, and in front of guards, they put the petrol oil on all school tents and carpets and they burned them. Also in order to frighten the villagers they fired their guns in the air at least two times. And then they escaped.

The following day, the official said, he saw “the girls really looking shocked. Some of them were even crying.” The school reopened that day, and the head of school “told the students that they will continue the school in open air.” Many girls returned to the school, the official said, but “there are a few families who are scared to send their children to school.”

This incident followed a failed attempt to break into the school some twenty-five days before, the official explained.

|

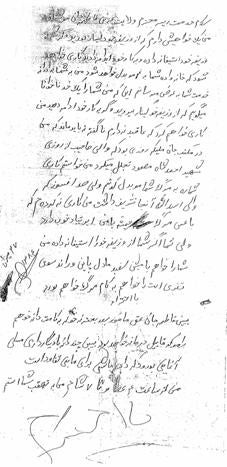

Night Letter from Wardak

By the Name of the Great God A Hadith [a saying of the Prophet Mohammed]: Whoever acts like them is one of them [Arabic]. Respected Afghans: Leave the culture and traditions of the Christians and Jews. Do not send your girls to school, otherwise, the mujahedin of the Islamic Emirates will conduct their robust military operations in the daylight. Wa-alsallam By the office of the Islamic Mujahedin |

Wardak Province

Wardak province, southwest of Kabul, straddles the road from Kabul to Kandahar. Abdul Rabb al Rasul Sayyaf, a warlord with a long record of human rights abuses as far back as the 1980s to the present, exercises a great deal of political and social influence over the province from his neighboring stronghold of Paghman.

Efforts to educate girls in Wardak have faced serious difficulties. According to official statistics from the Ministry of Education, in 2004-2005, only a quarter of students enrolled in school were girls227; in one district, Saydabad, the education director placed the proportion lower, stating that girls and women made up only around one-fifth of the district’s students, even counting those attending NGO schools, some of which may not provide formal education. There was one high school for girls that, in 2005, ran only through grade ten.228

Wardak experienced a series of attacks on schools in 2005 and threats against schools, teachers, and other education officials. In December 2005, Human Rights Watch interviewed several teachers and education officials from the province who at first denied there were any security problems, then admitted that problems did exist, but blamed the Taliban—even though the province’s distance from the Pakistani border and the influence of Sayyaf’s forces make such a contention unlikely.

Human Rights Watch collected evidence of mines being left in two girls’ schools in Saydabad district shortly before the September parliamentary elections. Theanti-tank mine left at Malalai girls’ school, the official told us, destroyed the chairs and the tables, but not the roof and walls. The official visited the school shortly afterwards. “The mine was very big and heavy, but the person who was doing it didn’t set it up right . . . so it was not totally blasted,” he told us. The school principal called him and the Afghan National Army, he said, but the army did not respond, so he and others cleared the mine shrapnel and searched the school themselves. “We asked the ANA and the police to search for them but they didn’t. Nobody pays attention, so that’s why we requested the search for the people who made this violence.”229

An anti-tank mine was also left in another girls’ school in Shehabad district around the same time but was found before it exploded. Around 180 to two hundred girls in grades one to six attend the school, a teacher told us.230 According to the teacher, at around 7:00 in the morning, shortly before classes were to start, children were arriving at the school and discovered a clock in one of the classrooms. When her son came and told her about it, she went to investigate and described what she saw:

It had a round shape and a timer. There were two wires coming out of it connected to the timer. The clock was set for 9 a.m. It was a little bit far away from the mine. There were wires connecting it to the bomb. The mine was round. It was put on the side of the class. A bag was put on it. . . . I started taking students out of the school and sent my son to call his father. . . .

He informed the education director who made contact with the PRT and ISAF in Ghazni, but the PRT was on a mission so they didn’t come until the afternoon.231

When the PRT came, they exploded the mine in a field, other eyewitnesses confirmed.

In response, the teachers moved the school into the courtyard of a private home to finish the school year, but expressed concern that this would not be a permanent solution. “That’s why we have bought you to see all of these problems because we see the commitment of villagers to keeping the school. We want the authorities to provide security for the school so we can continue to work. It is very difficult for us to keep it. There is no bathroom, no water supply. . . . We were scared but we didn’t stop running the school. I didn’t even let my children go to the school building because there was no door, no window, no wall, so we didn’t feel secure studying there. I am worried that there is no guard, so how can I take the students there?”232

Teachers in a home-based school a few kilometers away described the impact the incident had on them and their students:

We were scared. . . . Some of our girls are small and they were afraid when they heard the news. . . . They kept asking us will it happen in this area. So we encouraged them because the students were worried and scared about this. In the lower grades some didn’t come for one or two days, but the girls in the higher grades like to come so they brought them with them.233

It is unclear who planted the mine; however everyone we spoke with told us that they believed it was not the Taliban but rather people from the area opposed to girls’ education. Shortly before the incident, a night letter was left in the local mosque saying that the school should be closed. A local official told us that it “may have been the work of some thugs of a commander who are now in jail” because they were later caught at a police check post with a rocket in their car.234 The official was afraid, he told us, to say the name of the commander out loud: “The people in the village know him. He hasn’t been caught—he’s still there.”235

Around the same time, night letters were left at two schools in the district, the local education official said. “Almost every school has received threats. Now we have gotten used to it. It looks strange to you but we are used to it.”236 He added that around the same time, rockets were fired at night which he believed were aimed at the Ansari boys’ school, but they missed and fell nearby.237

The attacks continued in 2006. According to ANSO, the United Nations, and press reports:

- April 3: a school in Sheikh Yasin village, Chak district, was set on fire; a suspect was arrested on May 4.238

- May 10: unknown men fired four rocket propelled grenades at a girls’ school run by an NGO in a private house in Doh Ab village, Saydabad District, at night. The buildings were damaged but there were no reports of casualties.239

- May 11: At around 1 a.m, two rockets were fired at a girls’ school in run by the NGO Aid Afghanistan in Tangi.240 A third rocket was also fired towards another building of the school in a different part of the village. The school’s principal, who lived nearby, went looking for the perpetrators, believing they fired the rockets from an open field just outside the village. He did not find them but did find four un-exploded explosive devices planted around the school building. Shots were then fired at him, but he escaped and called the authorities, who arrived some four hours later at around 6 a.m. According to the NGO’s director, the school suffered minor damage, including broken windows but no persons were hurt. However, as of May 16, the school was closed and its 300 students unable to go to school. Posters had also been put up in the village, threatening the principal and his family because he was involved in girls' education.241

Laghman Province

Laghman district, southeast of Kabul on the heavily trafficked road to Jalalabad and on to Pakistan, had until early 2006been considered relatively safe.242 However, the frequent passage of coalition transports drew attacks from opposition groups in 2006, including on government officials.243 Gulbuddin Hekmatyar’s forces are particularly active in Laghman, and are generally viewed as the prime suspect behind attacks on schools, in light of the group’s rhetoric of attacking the central government as a “tool of Western imperialism” and its commitment to fundamentalist religious education.244

Laghman’s relative quiet has allowed more girls to enroll in school. In 2004-2005, 39 percent of students enrolled in school in Laghman were girls.245 But even here, attacks on teachers and schools have taken place and seem to be occurring with increasing frequency.

Education officials from Laghman told Human Rights Watch that in January 2006 unknown armed men with covered faces burned a school some three kilometers to the west of the provincial capital of Mihtarlam.246 The men tied up the officials, ordered them not to work in schools again, said they were against education, and then set the school on fire.247

Also in 2006, according to ANSO, the United Nations, and press reports:

- On or about January 27: a group of unknown men set fire to Haider Khani girls’ school in Mihtarlam city, destroying two classrooms.248 The men also held two local engineers and another man from the village hostage overnight, releasing them unharmed the next morning. According to U.N. reports, the school was set on fire again around March 18.249

- On or about January 30: men broke into Bagh-e Mirza girls’ school, tied up two guards, and attempted to set a fire in a classroom. Villagers heard noise and intervened and the men escaped.250

- February 8 or 9: around twenty armed men set fire to Mandrawol girl’s school in Qaeghayi district after tying up several janitors or guards. Schoolbooks and copies of the Quran were reportedly burned.251

- On or about March 18: the administration department and the storeroom of a boys’ school that girls attended was set on fire in Mashakhil village, Mihtarlam district.252 Police later arrested suspects.253

- April 11: one of two rockets fired near Mihtarlam city fell between a school and health clinic in the Shahr-e Now area, damaging the school.254

- May 1: unknown individuals started a fire at Armul Primary School in Mihtarlam district. According to ANSO, villagers managed to control the fire, but one library and the hall of the school were partially burned.255 However, District Education Department Director Asiruddin Hotak told journalists that the whole building, including the library, administrative block, and classrooms, was gutted.256 According to the school’s principal, Nasima, twelve teachers were teaching 650 girls at the school. A self-described Taliban spokesperson said that the Taliban were not involved.257 On May 12, the National Security Directorate reportedly arrested an Afghan man suspected of being involved.258

Human Rights Watch visited rural Laghman in June 2005 and collected information about threats against girl students in November 2004. One teacher told us that she used to teach first grade in a girls’ school located in the next village, about a twenty minute walk from her own.259 (There was a boys’ primary school in her village but no girls’ school.) Around November 2004, she found a letter left on the route. “I remember the letter very well,” she told us. “It was a clear threat to me and all students going to that school.” The letter read, in Pashto: “To all girls’ students and school teachers, teaching in girls’ schools! We warn you to stop going to school, as it is a center made by Americans. Any one who wants to go to school will be blown up. To avoid such a death, we warn you not to go to school.” Because of the letter, she said,

I along with my family decided not to go to school because those who are warning us are quite powerful and strong. We are ordinary people and we can not challenge them. Also I asked the girls from my village not to go back to school. At that time the school was in tents, but now there is a nice building. All the girls from my village would really like to attend that school, which has very clean rooms, black boards, and a good environment, but the problem is security—what will happen if they really plant bombs on our way? That’s the reason.260

A fourteen-year-old girl who lives in the village where the school is located confirmed that girls from the neighboring village no longer attend. “I am very upset for my colleagues from other villages who cannot come to school,” she told us. “They were coming to our school and we were happy to study together, but I know something has happened and now no one is coming from that village.” After the other girls stopped coming, she said, the men in her village put a guard in the school, and she and all her friends continued to wear burqas to and from school. “We attend school with fears and worries,” she explained, “but we are happy at least to use this chance.”261

The teacher said she was not sure who was responsible, but that she and her family suspected the local commander, who is allied with Gulbuddin Hekmatyar’s Hezb-e Islami.

Human Rights Watch also spoke with other individuals in the area connected with education who did not wish to be named about the girls’ school. One man told us that “once during the last year when the school didn’t have any building and the students were studying under tents, the school was burned. They burned all the tents and carpets and blackboards. But then, recently, the villagers with the help of [an individual in the community], managed to build the school.”262

A teacher at another girls’ school in rural Laghman described a night letter left in the mosque at the end of November 2004. When her husband brought it to her, she said, she remembered reading the following:

These girls’ classes in the village are made by Americans. It is not a school; it is a place for bad women. This is a place for revelry. We warn you to stop sending your girls to these classes or you cannot imagine the consequences. Your classes will be blown up by a bomb, or if any of your daughters is raped or kidnapped, you can not complain later on. We now ask you to stop sending girls to school.263

The school then closed for a month, until the mullah decided that it could reopen. But one quarter to one third of the girls never returned, she told us. Although the letter was unsigned, she said, people in the village believed they knew the local people responsible. However, “if we give details and names, then we have to leave our houses and become refugees. So we prefer not to name them.”264

|

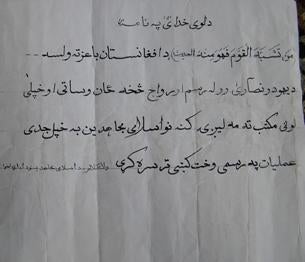

Night Letter from Kapisa

Taliban Islamic Movement Representative of Parwan and Kapisa Provinces Warning Date: (not mentioned) Number: (Not mentioned) 1) This is a warning to all those dishonorable people, including ulema and teachers, not to teach girls. Based on the information given to us, we strongly ask those people whose names been particularly reported to us, not to commit this act of evil. Otherwise, it is they who bear all the responsibilities. They have no right to claim that they have not been informed. 2) This is to inform all those who have enrolled at boys’ schools to stop going to schools. An explosion might occur inside the school compounds. In case of getting hurt, it is they who bear all the responsibilities. They have no right to claim that they have not been informed. |

Impact of Crime and Impunity on Education

Not all attacks on teachers, students, and schools stem from political or ideological opposition to the central government and its international supporters. Much of the insecurity plaguing Afghanistan is a result of a breakdown in law and order, driven in large part by the country’s exploding narcotics trade and abetted by the tremendous weakness of the country’s police and judiciary.

Aggravating the problem is that in many areas of Afghanistan, security forces are essentially simply reconstituted local militias, either directly or indirectly involved with the armed groups attacking teachers and schools. A police official from Wardak told Human Rights Watch:

If the police were clean, they would be effective. In theory, yes, the police could provide the security that you want to schools, but they’re not strong or clean enough. People want good police to protect their children. If the police are polluted, don’t expect too much from this country.

The police are connected with the Taliban, sometimes, Al Qaeda, and criminal networks. It is easy to understand why the police have not protected schools and investigated their attacks. Sometimes they are involved in the crimes or agree with the criminals.265

In this environment of impunity, criminal activity is a systemic threat to the well-being of the Afghan people, as politically motivated groups also engage in common brigandage, extortion, and intimidation to finance themselves and establish regional authority. Children are frequent targets of criminals and criminal acts. Various, often unidentified armed groups and individuals have targeted children, in some cases on the way to school, for kidnapping for ransom, rape, forced marriage, and other crimes.266 Lawlessness, and especially attacks on children, seriously obstruct education throughout the country.

Rumors about kidnappings of children swept Afghanistan in 2004 and 2005, fueled by a number of apparently real cases throughout the country. From July to December 2004, the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission officially registered fifty kidnapping cases in Kabul, staff told us, but they believe there were many more unreported cases.267 In 2005, at least fifty-one child kidnappings and attempts were reported by ANSO.268 The kidnappings had a powerful effect even on those not directly connected with the incidents. For example, the director of a girls’ school in Herat told us in July of 2005 that in the last year, “the rumor of kidnapping children has affected attendance of our students . . . nowadays it is again improving.”269 Similarly, a teacher in Mazar-e Sharif also told us that when a kidnapping occurs, “parents don’t send their boys and girls to school for some time.”270 A teacher from Deh Yek district in Ghazni said school attendance at his school decreased severely after a nine-year-old boy was kidnapped and sexually assaulted in May 2005.271

In Kandahar city, Human Rights Watch interviewed a mother who withdrew her three daughters from primary school after a girl in one daughter’s class was kidnapped and killed.272 Her cousin’s husband found the classmate’s body around the time of the Persian New Year (March 21) in 2005, the mother said, “dead with her books all around her. He took her to the hospital and found out that the girl was from the school where my daughters attended.” After that, she said, “I took them out and since then they have never gone back. . . . They were afraid. They themselves didn’t want to go.”273 The mother emphasized that she thought education was “a good thing.” “The girls are very smart—they ask the boys all the time about their books. I can see that they are interested. . . . We understand that school is good for the future. It’s just the talk of the community, the threats that prevent us from allowing our girls to continue.”274

Although parents of boys also told us they feared crime against their children and boys have been the target of well-publicized kidnappings,275 the fear of violence and the likelihood that it will never be punished has an especially profound effect on girls and women, both because they are targeted for gender-based violence and because of the additional stigma and other consequences that fall on female victims.276 Teachers, students, and NGOs report that sexual harassment of girls en route and threats of gender-based violence are significant problems for girls’ education.277 In cases of forced marriage or other forms of gender-based violence, there are few avenues for redress. Social stigma often prevents women and girls from reporting such cases, and even if they do, the lack of clear legal standards, the apathy and lack of appropriate training of the police, as well as the dominance of local warlords and their supporters who might be implicated result in virtual impunity for perpetrators. According to an Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission staff member:

There are probably many hundreds of cases that Afghans don’t want to register because they consider it shame to the family. For instance, I know a woman [whose] daughter was kidnapped four months ago, but it has not been reported to the police. But she has consulted me—just sharing her grief with me. Her daughter was twenty or twenty-one years old and teaching at a high school. . . . The father says it’s not good to look for her and tell people [what happened].278