<<previous | index | next>>

VII. Problems in the Disarmament Programs in Sierra Leone and Liberia [1998-2005]

The commander called a meeting to collect our weapons.

The bosses said they would contact us to go for training and the extra money,

but they never did. Some of the guys later attacked the DDR building, but by

that time I was into the next war so just said forget it.

– Patrick, 24 years-old, Sierra Leone

Nearly all the ex-combatants interviewed for this report were eligible for participation in United Nations funded and administered disarmament and training programs. These programs had their successes, but also their failures. For example, the Sierra Leonean program disarmed over 70,000 combatants, but up to 2,000 are thought to have been re-recruited and indeed later fought in wars in Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire.91 Considering that many of West Africa’s recent conflicts started with a small number of combatants – often several hundred – and that the bulk were provided through abduction and forced recruitment, even this small failure has potentially broad ramifications. The Sierra Leonean program has recently finished and the second Liberian program is on-going, but the effectiveness of each program still needs to be evaluated. While successful disarmament programs are crucial to reintegration of ex-combatants back into society, they should not be expected to bear the entire burden of creating social stability following an armed conflict. Far reaching efforts must also be made to provide for parallel community development programs assisting the general population whose lives, communities and villages were destroyed during armed conflict.

The ex-combatants interviewed were potentially eligible for participation in one, two, or even three of these programs: Liberia (1997), Sierra Leone (1998-2003) and Liberia (2002-2005). The first Liberian disarmament program provided limited financial opportunities and almost no training. Combatants eligible for this program said they either had not bothered to enroll or had enrolled but perceived little economic or social benefit from the program. The majority of interviewees had participated in one or more of the later two programs: the Sierra Leonean Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (DDR) Programme, and/or the second Liberian initiative, the Disarmament, Demobilization, Rehabilitation and Reintegration (DDRR) Programme.

Both the Sierra Leonean and Liberian programs were jointly administered by the respective governments through a national commission, and the U.N. peacekeeping missions. The disarmament portions of the programs were funded through assessed U.N. contributions92 while the rehabilitation and job training sections were funded through donations, managed through a trust fund. The trust fund in Sierra Leone was managed by the World Bank,93 while the trust fund in Liberia is managed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).94

Sierra Leonean Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration Program (1998-2003)

In Sierra Leone, some 72,490 combatants disarmed through the DDR Program.95 After turning in their weapons to U.N. peacekeepers serving with the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL), ex-combatants entered a demobilization camp where they spent varying amounts of time, from a few hours to two weeks.96 In the demobilization center, they received classes on civics and democracy.97 Some, but not all, ex-combatants were also given classes on HIV/AIDS education and family planning.98 Unfortunately, efforts to include a class on human rights education were, at the time, considered too controversial and this type of education was excluded from the program.

After completing this initial stage, ex-combatants received a sum of 300,000 leones (approximately US $143), called a Transitional Safety Net Allowance (TSA).99 When the training programs were prepared to take them – sometimes after considerable delays – they entered the job training or education program for which they had signed up. During the six-month training period, ex-combatants were paid a small monthly stipend. Upon completion of their course, they were to be given tools they could later use in their respective trade. The trades offered included carpentry, auto mechanics, masonry, tailoring, agriculture and a few others. Few combatants were given the opportunity to continue with primary or secondary education, although a limited number, including many commanders, were supported through secondary school or local university. At the beginning of the process, each combatant was given an identification card which had his picture and which served as his passport to enter all subsequent phases of the program.

Liberian Disarmament, Demobilization, Rehabilitation and Reintegration (2002-present)

The second Liberian disarmament program – the Disarmament, Demobilization, Rehabilitation and Reintegration (DDRR) Programme – is largely modeled after the program in Sierra Leone, although the Liberian program offers more opportunities for education and training. Under the Liberian program, the combatants were to be transferred to a cantonment, where – as in Sierra Leone – each combatant would surrender his or her weapon, register for the program, and receive an ID card.100 Each combatant would receive a reinsertion benefit: the first payment of the reinsertion benefit was to occur upon discharge, and the second three months later.101 As part of the reintegration program, each combatant was to be provided with the opportunity to acquire basic skills “to support themselves and to participate in the community reconstruction process.”102 Ex-combatants were to select one of four training programs: formal education, vocational training, public works, or agriculture/ livestock/ fishing.103

As of February 2005, the United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) had disarmed and demobilized some 103,019 combatants.104 This is nearly three times the expected number of 38,000 for which the Draft Interim Secretariat had budgeted in 2003.105 The program has been criticized for not having strict enough admittance criteria, a factor that may have contributed to the inflation of the registration numbers. For instance, only 28,222 serviceable weapons had been collected by January 2005 – approximately one weapon for every four registered combatants.106

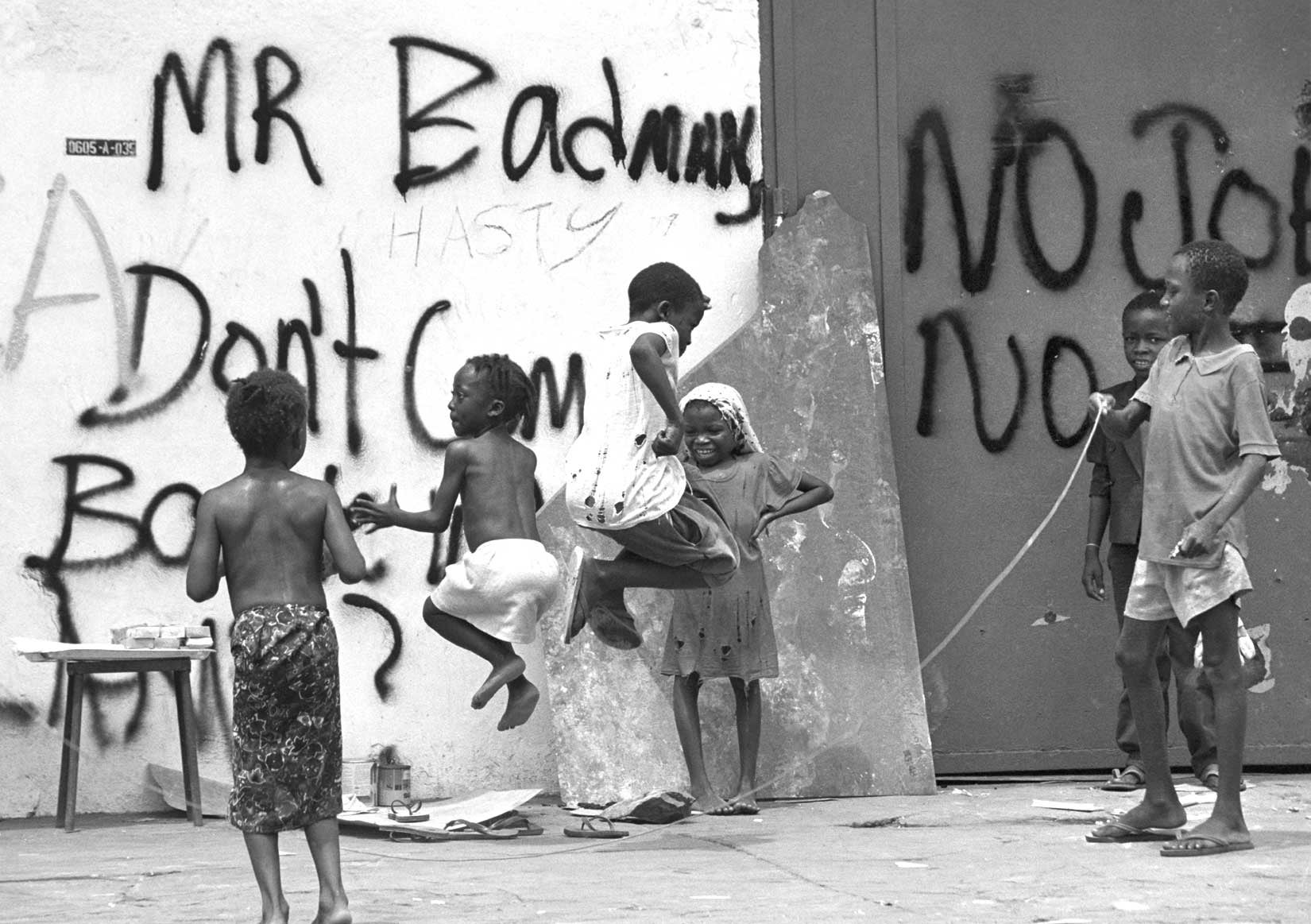

Liberian children jump rope during a lull in the fighting which engulfed the Liberian capital Monrovia in April 1996. Hundreds of civilians were killed and thousands more wounded during the 1996 clashes between Charles Taylor’s NPFL and Roosevelt Johnson’s ULIMO-J. © 1996 Corinne Dufka

There is a significant possibility that many who registered were never, in fact, combatants: only 150 rounds of small arms ammunition (SAA) were needed to enter the program.107 The screening for adult fighters was less stringent than the corresponding process for child fighters; consequently 70-80% of the SAA entries were adult males.108 There were considerable inconsistencies in enforcement of the eligibility criteria for DDRR, particularly in the screening processes conducted by MILOBS and NGOs.109 These eligibility criteria were flexible in the beginning and were never thoroughly reviewed, damaging the credibility of the program.110

Former commanders were present throughout the program, purportedly to verify the identity of former combatants.111 The relaxed eligibility criteria and presence of commanders throughout the process led to the admittance of a significant numbers of individuals unrelated to the fighting forces – most believed to have been brought in by commanders who stood to gain economically from the practice. This may have also led to the exclusion of others unwilling to share part of their benefits.112

In mid-2004, several cases of young men carrying ammunition crossing into Liberia from Sierra Leone to enroll fraudulently in the DDRR program were reported, according to the Sierra Leonean Police. Sierra Leone Police officer Augustine M. Kalie, who is based in the southern town of Bo, described one case involving some thirty-eight Sierra Leoneans:

In June 2004 we received information of people organizing to take Sierra Leoneans over to Liberia to disarm so they could get a percentage of the DDR benefit. An intel officer first came with the information that a group of young men would be moving to the border. That day in June, we organized a team of officers and had them stop suspicious cars going along main road between Bo and the Liberian border. They stopped a Mazda truck with about 40 footballers all between 15-25 years old. They said they were on their way to play a match at Jimmi Bagbo – some 30 kilometers south. We found no arms/ammo and since they had the right to travel, we let them proceed. But we contacted our officers at Jimmi and were told the truck had continued South. Later we were told they’d crossed to Zimmi near the border. We stopped them there and brought 38 for questioning in Bo. Several of them told us that they’d been organized by a former LURD rebel named CV to go to disarm in Liberia and then split the profit with him and another commander. Of the 38, some were civilians, some school boys who’d been roped in and others CDF fighters who might or might not have served in the Liberian war.113

The striking disparity between the number of combatants expected to disarm and the number who were allowed entrance created serious difficulty for implementation of the DDRR program. In particular, the disparity affected organizations involved in raising money for the rehabilitation and reintegration phase The financial crisis led to the demobilization part of the program being shortened from twenty-one to five days, and the amount budgeted for each combatant being decreased from US $1,400 per person to just under US $800. Most alarmingly, it resulted in a severe funding shortfall of US $39 million in the rehabilitation and reintegration phase of the DDRR program which at this writing, leaves some 47,000 ex-combatants at risk of missing out on job training and education.114 It also undermined what DDRR program officials envisioned to be a seamless transition between the “DD” or disarmament and demobilization phases of the program, and the “RR” or rehabilitation and reintegration phases of the same. 115

During January 2005, some 4,000 ex-combatants enrolled in secondary schools were expelled because the DDRR program had failed to cover their school fees, provoking protests from the students. While their fees were eventually paid, tens of thousands of others are waiting to enter school and job training. Liberians, long fearful of this volatile population, are concerned at what will happen if ex-combatants are left idle. The long wait between disarmament and entrance into a job training or education program also leaves them vulnerable for re-recruitment into another armed conflict.

Payment to Demobilized Children in Liberia and Increased Risk of Re-recruitment

For the first time in any demobilization exercise, the Liberian DDRR program adopted the policy of giving demobilized child combatants cash payment, in addition to other benefits. According to United Nations employees and aid agencies working with the children, this policy not only undermined efforts to successfully reunify and reintegrate them back into their families and communities, but also made them more vulnerable for re-recruitment into future wars.116 Children who entered the DDRR program were given the same Transitional Safety Net Allowance (TSA) – US $300 – as adult combatants. The children received the TSA after, in principle, spending from three to twelve weeks in a residential facility called an Interim Care Center (ICC), which was designed to provide counseling and facilitate reunification with their families and communities.

However, giving children money as part of the disarmament program has reinforced the link between child soldiers and their commanders, who often insisted on being given a portion of the child’s TSA. It also undermined the process of reintegration by making the child feel under pressure to leave the ICC in haste. As one aid worker put it, “The children should have felt at peace to stay in the ICC’s for as long as they needed. But instead their families and commanders pressured them to get out quickly, so as to have access to the money.”117 The policy also left the children who returned home to their communities with a large sum of money by Liberian standards, open to exploitation by commanders, family members and others.

In some cases, the financial arrangement solidified the connection between child combatant and commander, making it less likely that the former child soldier would return to their families and civilian life.118 According to one aid worker, many children who had lost touch with their families felt under pressure from their commanders to tell the ICC social workers that their commander was a parent or close family relative, thus severely undermining the reunification process; “instead of waiting for us to find their families and reunify them, the kids were forced by their commanders to say that they were a close family relative of his – even a son or daughter – all to get access to the child’s TSA.”119

This policy also increased the likelihood of the children’s re-recruitment because the commanders were more aware of the children’s whereabouts in the event of a new armed conflict. The children could also potentially be seen by the commander as a future financial asset; that is, if recruited, the child could again be a ticket to future disarmament program pay-outs.120 Aid workers said that the financial incentive actually resulted in commanders bringing children into the DDRR program who had not previously fought in an armed conflict, and more disturbingly, served as the motivation for children with no prior experience in war, to join a faction in Côte d’Ivoire in anticipation of a future disarmament payoff there.121

Those defending the policy noted that the payment of TSA to children and its attendant financial motivations for the family, may have actually contributed to a “speedy family reunification.” They cite as evidence the fact that almost 100% of children have been reunified with their families. However, social workers doing home visits to recently reunified child combatants expressed alarm at the seemingly high numbers of these reunified children who have been re-recruited to fight in Côte d’Ivoire.122

Young fighters with the National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL) sit on a street corner during a lull in the fighting in April 1996. Many fighters from Sierra Leone fought in Liberia both with the NPFL and, after 1997 when NPFL leader Charles Taylor became president, as Liberian government militias. © 1996 Corinne Dufka

The problem of children being vulnerable to re-recruitment is compounded by the lack of support for schools attempting to rehabilitate child ex-combatants.123 Without adequate educational opportunities, these children will remain vulnerable to the parasitic economic interests of their commanders.

Risks of Failure in the Disarmament Program in Liberia

The experiences of the regional warriors interviewed for this report demonstrate the potential for failure in the current disarmament program in Liberia and in any similar future programs. The majority of those interviewed had negative experiences with the DDR program in Sierra Leone; the program’s failure to engage them contributed to their decision to take up arms with another armed group. Numerous combatants who were denied entrance into job training programs while going through Sierra Leonean DDR cited their disappointment and frustration as key factors in their decisions to cross a nearby border, pick up a gun, and once again return to the frontline. A second chance for job training or education through participation in the Liberian DDRR program was an additional motivation for crossing the border; this plum was frequently offered by recruiters as well.

Combatants interviewed by HRW consistently described a high degree of anticipation regarding the job training and education component of the Liberian disarmament program; they expected this component to make a significant difference in their lives. This was all the more important because the US $300 Transitional Safety Net Allowance was often “eaten up” very quickly – sometimes within a few days – by the daily demands of the nuclear and extended family, by family emergencies such as illness, complicated births or funerals, or to support small, subsistence-oriented businesses.

The interviews revealed three key problems within the Sierra Leonean DDR program and to a lesser extent the Liberian DDRR program. The first was corruption by commanders and to a lesser extent, DDR/DDRR program employees who subverted benefits destined to their subordinates to themselves. Another was an inadequate grievance mechanism to submit complaints. Finally, many encountered difficulties in finding a job after training, due, in part, to a surplus of ex-combatants offering the same skill sets.

Corruption by Commanders and DDR/DDRR Program Employees

Many of those interviewed discussed the low-level corruption pervasive in the DDR/ DDRR processes in Sierra Leone and Liberia, focusing in particular on the corrupt behavior of former commanders. The commanders exercised undue control over the DDR / DDRR processes by manipulating the combatant’s enrollment in and access to program benefits. This type of corruption which involved the fraud, embezzlement, diversion or misuse of disarmament benefits was not always immediately visible and evident, and was not directly addressed by those individuals responsible for managing either program. In both the Sierra Leonean and Liberian DDR/DDRR programs there appeared to be systems in place – including audits and financial oversight by an independent consultant -- to monitor the potential for high level corruption.124 However, the commanders’ participation in the implementation of the program was not sufficiently monitored to stamp out corruption at the lower level.

Combatants consistently complained that their former commanders had a great degree of control over their access to DDR/DDRR benefits. These benefits were sold by the commanders in exchange for a “cut” of the pay-out. The commanders often appeared to act in collusion with Sierra Leoneans employed by and working within the Sierra Leonean National Commission for Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (NCDDR). The problems with corruption began with the issue of who maintained possession of the key element of any DDR program: the arms. In both Sierra Leone and Liberia, there was a lag of weeks or months between when the DDR/DDRR program officially commenced and when the demobilization centers where the combatants spent several days or weeks were ready to open their doors. In the interim, both UNAMSIL and UNMIL were anxious to get the guns off the streets. They were concerned for two reasons: the potential for combatants to backslide on their commitment to the disarmament process – as was the case in Sierra Leone in May 2000; and, criminality in the face of an inadequate police presence.125

In both Sierra Leone and Liberia, UNAMSIL and UNMIL allowed the commanders of the various armed factions to take control of the weapons.126 While this may have been useful from a security point of view, it also consolidated power in the hands of the commanders. According to many of those interviewed for this report, the weapons the commanders collected during the Sierra Leonean and Liberian disarmament exercises were at times kept by the armed groups and at other times turned over to the peacekeepers.

In principle, the commanders were supposed to submit lists of fighters from whom they had received weapons. However, according to the ex-combatants interviewed by HRW who went through the process in Sierra Leone, the commanders could include on the list, and once the process began, admit into the program, anyone of their choosing. They were also in a position to coerce their subordinates into giving a percentage of the benefits or at worst, “sell” the place in the DDR program to a friend or relative, who was in turn willing to give the commander a cut from “their” DDR benefits.

Commanders pledged to provide detailed lists of those in their units to the U.N. and national administrators of the disarmament programs – indeed it was supposed to be a precondition to enroll in the process. However, there was no systematic provision of lists by factions involved in either the Sierra Leonean or Liberian armed conflicts. Minutes reflecting a discussion with United Nations and NGO workers to evaluate the disarmament exercise in Liberia noted, “the difficulty in the verification of real XC’s [ex-combatants] due to unavailability of reliable information or lists about the ex-combatants prior to the commencement of the programme.”127 When lists of individual units were provided, those interviewed described no process for verifying that the names on the lists matched the actual fighters who had served under the commander. In any case, the lists appeared to be easily manipulated, and in many cases, never materialized. The U.N. and national administrators of both the Sierra Leonean and Liberian disarmament processes appeared to provide inadequate scrutiny of this process.

The problem of corruption within the Sierra Leonean DDR program, as described by those interviewed for this report, was particularly pronounced within the Sierra Leone CDF militia. Since most CDF militia men had initially volunteered for service out of genuine concern for their communities, they described a profound sense that they had been betrayed by their commanders and government militia officials whom they accused of stealing their benefits. The gravity of their experiences varied; some were kept out of the process by their commanders all together and never received their ID card, which was the passport to entry into the rest of the program. Some received their ID card and some benefits, but were kept out of the job training component after their commanders instructed them to handover their ID cards for safe-keeping, or after their places had been taken by people using their ID numbers. Mid- and high-level commanders had access to larger weapons which could be used by two or three combatants when disarming. According to some ex-fighters interviewed by Human Rights Watch, the commanders trained friends and relatives on the use of these weapons, and then sent them to enroll in exchange for a portion of the benefits.

A thirty-five-year-old regional warrior, who joined the CDF militias in 1994 after witnessing a massacre by the RUF, described his disappointment over being denied access to the DDR program by his commanders and how he was later recruited to fight in Liberia alongside his former enemies:

I served with the CDF for seven good years but our elders played a trick on us. When it came time to disarm, I and many of my friends were not allowed. Instead, the commanders took their own children and friends who never fought for this country and disarmed them instead of us.

The problem was that not every Kamajor fighter had a gun. Before DDR began, our commanders told us to hand in the guns and then they controlled who got to disarm and who didn’t. From my village we were about thirty Kamos who couldn’t disarm. It was the same in other villages. Meanwhile a cousin of mine who never fought, but who knew the commander got the DDR card on the condition that he gave 100,000 of the 360,000 leones to the commander. That cousin went for a six months training in masonry.

We later learned that the betrayal started way before DDR. The government was sending a lot of money for rice to feed us on the frontlines – but we never got it. The elders responsible for distributing it were selling it and sharing it among themselves. We saw the rice coming into Kenema in big, big trucks, but only the big men got it. And we went to the front hungry.

After the war – in 2001 – my intention was to learn to be a mason so I could support my family. But when I was kept from entering the DDR program, I went to fight in Liberia with those fighting to defend Charles Taylor. One day a friend who was with the RUF came to me and told me about the Liberia operation. He said it was going to be a six month operation and that if we survived we’d be given $100 US.128

After finding that his commander had used his ID number to register someone else in a computer training program, another CDF member went on to fight with the LURD:

I disarmed in Zimmi in 2001, got my first 300,000 leones [U.S. $125] and signed up to study computers. Some weeks before the course was to begin, our commanders asked us to send our number and name to them. I did so thinking I was about to begin my course, but that’s where the game was being played. When I went to NCDDR to register, they said the number which corresponded to my card had been taken. I told them to check again, but they said, sorry, that number has already been benefited. I fought every kind of way. My commander who did the dirty trick, told me to go to NCDDR but they said there was nothing they could do – if the computer says the number is taken, then it’s taken, full stop. These people are discouraging us, the youth. The privileges given by the international donors have been abused by these people. Look at me I’m a young man. I want to lead a good life. But without education anything can encourage me to join and do bad.129

These problems seemed less pronounced in Liberia, likely due to the more relaxed entrance criteria. However, there is still cause for concern, as a twenty-four-year-old mid-level commander who disarmed in August 2004 explained:

There is corruption there. The commanders are saying each rifle has a commission – they are selling the places. The commanders have a lot of guns, and he gives the guns to those he knows will give him a commission. I know plenty of true militia boys who’ve not seen any benefit from this war.130

Since not every combatant in the rebel factions and civilian militias had their own weapon, the disarmament programs provided for larger weapons like mortars and rocket launchers to admit more than one person. This provided yet another avenue for corruption. This mid-level Sierra Leonean CDF commander described how during the Sierra Leonean DDR program he helped friends and family to enter into the disarmament program this way:

I helped 12 people get into the DDR program; they were never Kamos, but I did it to help them go forward. You see, the RPG carries two people; one for the launcher and one for the bomb. The LMG carries two – the one who fired and the one who carried the chain. Then, we were finding guns in the bush to give to people to disarm with. People came crying to me asking for help and this is what I did. We worked together to make our future brighter. Before we went to the DDR center, we trained them enough so the DDR people would think they knew how to use them. They got the 300,000 and they gave me 150,000. That’s 150,000 for them to start a new life and 150,000 for me. Two were family members, a few others were young people in their teens, and a few were friends of mine in the 40’s. Every one was doing it… these are our brothers and we did it to help them. It also helped the guns come out faster, so everyone was a winner.131

Many of those taking part in both the Sierra Leonean and Liberian disarmament programs were told by their commanders that paying them a percentage of their Transitional Safety Net Allowance was a precondition for enrollment. This was highlighted as a concern by numerous combatants interviewed for this report. It was also noted as a problem in the minutes from the Liberian “DD Wrap-Up” sessions: “Former commanders’ demands for their share of TSA (inclusion into the factions’ lists was a commitment to share the benefit, court cases by former commanders against children who have refused to pay) and the screening process posed challenges for CPAs [child protection agencies.]”132

A thirty-five-year-old Sierra Leonean, who disarmed in Kenema in 2001, described his commander’s admonition to some 300 CDF militiamen:

I stayed with the Kamajors until the end and disarmed in Freetown with an RPG. I got both installments of 300,000 leones [US $125] and trained in Kenema. I had to give 100,000 to my former commander. I had to. He gathered about 300 of us together and said that there had to be loyalty. That each of his boys should give him something. We had given our commanders our guns and unless we agreed to pay him something, when the time to enter the program came, we wouldn’t have been able to enter and get anything from it. .133

A twenty-three-year-old Liberian who disarmed in July 2004, described a similar gathering:

I joined the LURD in 2003 and was with them for about five months. I gave my gun to my commander in Tubmanburg in October 2003 during a huge assembly of LURD people. They then put my name on a piece of paper. Then in July 2004, Commander T called all twenty-five of us in his unit together and said, “You’re now going to enter the DDRR program and anything you get for me to be able to help me buy cold water, would be good. But you should definitely find something to give me.” After I spent five days at the DDR site, I got my card and the first payment of $150. All of us gave our CO $75 US. We didn’t give him all, only half. I gave it willingly.134

Several younger combatants who had lost or become separated from their families – sometimes as a result of an abduction or atrocity committed by the same faction with whom they fought – looked at their commanders as surrogate fathers or family members. After receiving their SNA some of these younger combatants claimed to have willingly given up to half of it to their commanders. A twenty-year-old Liberian who had been abducted by the NPFL and lost a leg while fighting in Côte d’Ivoire described the relationship with his commander:

I went to Ivory Coast with my commander M. Ten of us went and spent one year, three months there. M got us together and said, “Gentleman, we’re going to go on mission in Ivory Coast,” but he didn’t say who we were going to fight or why. He didn’t offer to pay us anything but he said not to worry – that once there, we’d have a chance to pay ourselves, which means loot. We were based in Danane – I never learned the name of the group we were with. When got my first DDRR installment of US $150, I give US $75 to M. I did it because he fought for me – he did everything for me. He made sure I had water to bathe and wash my clothes and food to eat. Many others didn’t give him any money and he didn’t ask us, but I did it willingly. I’m all alone now – when I was a child I really wanted to learn to be a doctor. I learned about medicine from my mother who was a nurse. But both my parents are dead. M is like my father and is still taking care of me. Like after I was wounded, it was M and my friends who helped me. They are like my family now.135

Many combatants described an element of intimidation or coercion between commander and subordinate, where the latter felt obliged to give the commander part of his benefits. The value in African societies placed on obedience to those in positions of authority was no doubt exploited by some commanders, as appeared to have been the case with this twenty-five-year-old Sierra Leone who disarmed with the CDF and went on to fight with the LURD:

In 2001 I disarmed in Bo town. I turned in my gun and received my DDR card and the first payment of 300,000 leones [US $125]. But about a month later, my Kamajor commander asked me for my card – what could I say, he was my boss. I was due another 500,000 of benefits; a second payment of about 300,000, a card to enter skills training and a monthly allowance while being trained, but I didn’t receive anything. I was told the commanders got everything.136

Lack of Grievance Procedure

The disarmament and reintegration programs in both Sierra Leone and Liberia lacked an independent, formal and effective grievance procedure which would have allowed combatants to seek redress for their lack of access to benefits caused by the corruption of their commanders and DDR/DDRR employees, or for any other reason.

In Sierra Leone, the Executive Director of the NCDDR, Dr. Francis Kai-Kai admitted there were some cases of corruption within the program: “The fighters blamed their commanders….we knew what some were up to. We also knew the commanders had people they favored and brought into the process.”137 He said complaints were in theory channeled to an office within the NCDDR called the Complaint Bureau, and if left unanswered could then be referred to the Sierra Leonean Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC). However, none of those interviewed for this report knew of the existence of the Complaint Bureau, and the few who had lodged complaints with the ACC were told by them that the matter was outside the ACC’s mandate.138 At any rate, both the Complaints Bureau and the ACC were located in the capital Freetown, which was hours away by road and in effect inaccessible to the vast majority of ex-combatants.

In Liberia, Charles Achodo, the Rehabilitation and Reintegration Officer for the Liberian NCDDRR program said, “There is no formal grievance procedure [within DDRR] which the ex-combatants could access to address problems. However, there are informal networks of counselors and military observers, which are available to respond to the legitimate grievances of the ex-combatants during the process.”139

In both Sierra Leone and Liberia, United Nations peacekeepers were responsible for supervising the disarmament and demobilization process.140 According to the fighters accounts’, whenever they told United Nations peacekeepers involved in either the Sierra Leonean or Liberian program about having been denied access to benefits, they were advised to lodge their complaints with the national employees at the national disarmament commission, the local arm of the program. This was affirmed by UNMIL representatives who told Human Rights Watch that when presented with a complaint from a combatant, “we ask them to go to NCDDRR, to the Liaison contact person who tells us if there are any problems.” When asked if they were aware of any such problems they went on to say, “We haven’t needed a grievance procedure because we haven’t heard of any problems; we have a well functioning relationship with the NTGL [National Transitional Government of Liberia] and NCDDRR. There is a strong presence of UNMIL and other NGO’s at the demobilization sites. The DDR site supervisors live there and have a very good grasp of what’s happening, so if there were any problems, they’d hear about it and since we receive daily reports from them, we’d hear about it too.”141

Relying exclusively on local employees from the local arm of the disarmament program to address complaints is inherently problematic because, according to numerous combatants interviewed for this report, many of the commanders and fighters alleged to be directly involved in the scams were working in these local disarmament offices. The local commanders were useful allies to the U.N. and national authority managing and administering the disarmament programs and were employed at the national, regional and local levels of the program. The level of corruption described by those ex-combatants interviewed by Human Rights Watch, however, suggests that these employees lacked adequate training, management, supervision and discipline both by their national supervisors and the U.N. staff providing oversight to the program.

Corruption and fraudulent practices by the local disarmament office in Liberia – the NCDDRR – was noted by a high level UNMIL official working with the DDRR program who, in a confidential memo obtained by Human Rights Watch, observed that, “Since the NCDDRR representative did not regularly pay his staff, using NCDDRR officers as a main method of sensitization caused a tendency towards local corruption and fraudulent working practices. Indeed several CIVPOL investigations were conducted into the fraudulent and coercive activities of some NCDDRR officials during the DD phase.” The memo went on to recommend that, “if permitted by UN financial rules, local NCDDRR staff should be financed and physically paid by [peacekeeping] Mission staff rather than passing a lump sum to any NCDDRR representative for disbursement by his/her own means.142

The memo went on to note the problem of understaffing within the DDRR program by qualified and experienced United Nations personnel. In Liberia, it was observed that, “[the] UNMIL DDRR Section was understaffed…the whole of the eight month DDR phase….was carried out by ten attached staff led by only three international staff with DDRR experience.”143

Several fighters described how international staff – including peacekeepers, U.N. employees from the disarmament unit and contractors – was often manipulated by commanders within the Sierra Leonean DDR programe. This former CDF fighter who was never allowed to disarm in Sierra Leone explained:

When we showed up at the DDR center, our commanders told us to wait. And while we were waiting, we saw their friends walking into the center and coming out with their DDR cards and benefits. You see, the whites [NGO representatives] and UNAMSIL people [peacekeepers] were there but they were strangers; they were controlled by our brothers. The ones who were lucky enough to get a card had to promise to give them the commanders a commission – 100,000 out of 360,000 leones. We were all born to this land; they are supposed to be our leaders. But they betrayed us. Sure we complained, but even if you know your rights, as long as you don’t have money, they’ll never take you seriously.144

Numerous fighters interviewed by Human Rights Watch described going back repeatedly to the DDR cantonment sites, faction headquarters, or to their commanders’ houses in an effort to gain access to their benefits, including entry into the program. Several were so angry that they beat up and threatened their commanders, and in a few cases destroyed their houses. One CDF fighter said he joined the LURD specifically to be able to get a weapon to kill his former commander. This Sierra Leonean explained:

For months I kept requesting my card but my Commander L, always said he’d misplaced it. I hollered at him and even punched him once, but it didn’t matter. I couldn’t complain to the DDR program because Commander L worked for DDR – in the computer room. I learned from my mates that he’d done the same thing to 20-30 other combatants – from different CDF units. We learned that he’d sold the cards and benefits for a profit to his friends. So they ended up getting the training that was meant for us. I wasn’t able to complain to our overall commander because he had some months earlier gone to fight in Liberia.145

A Liberian ‘General’ who readily spoke of being involved in current efforts to recruit his subordinates for a future military strike on Guinea, described how many Liberian commanders are taking half of the TSA given through the Liberian DDRR, and why he doesn’t believe any complaints against this extortion will be heard:

The ones I’ve pulled together have nearly all gone through DDRR and got their first $150, but for most of them, the Generals are taking half of it. My boys told me General X stopped his boys as they were leaving the VOA DDRR camp and took half the money from them there. We know this is going on but I’ve never gone to DDRR to tell them about it. And all the ones working there are the same generals anyway so what are they going to do.146

Another Sierra Leonean who went on to fight in Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire explained a similar experience and his successful efforts to resolve it:

The ones controlling the process were all ex-combatants. They’d take your picture for your card – which was the entrance to all your benefits – but two days later when you were told to come collect it, they’d say the card was missing. You’d walk up and down asking for it, but they’d already given it to someone else who used it to collect your benefits and enroll in training. You’d ask them again and they’d tell you to come back next week. You keep coming back and back until either you get fed up, or another worker agrees to take your snap again, but when they look you up on the computer, it would say you’ve already registered and received your benefits.

This happened to about thirty to forty Kamos I know, but all factions were grumbling about the same thing. We even gave the names of 100 or so who never got benefits and sent it to police, but they didn’t act on either. We had a riot at DDR where we broke windows of the sub-office of DDR. This was all about corruption. Eventually we complained so much that the head of DDR investigated. We gave him the names of those involved in one scam. The first was an ex-combatant known as S – who got so much money he bought a Benz and built a house. He was eventually suspended. The second was a civilian lady named A. who worked on the computers. She’s now living overseas. A third was another civilian named Mr. M. They all worked out of the pay office in the DDR office in Freetown.147

Inadequate job training options

Several combatants who went through the job training complained of the surplus of skilled workers in certain fields which had been created by the Sierra Leonean DDR program. They were unable to find gainful employment because the economy could simply not absorb so many new workers – primarily carpenters, car mechanics and tailors – flooding into the market. This nineteen year-old, a former RUF fighter who went on to fight with the LURD, explains:

In 2001, I disarmed with the RUF in Bo and got training to be a carpenter, and at the end, they gave me a set of tools. But after the six month course, I couldn’t get work. There were so many workshops – all over Bo. All over Kenema. Too many carpenters. After about seven months of trying, S ran into me on the street in Bo and told me, ‘hey, I want you to be with me in Liberia.’ She said they were paying $200 to go. I was fed up and since she used to be my general, I told her I’d go.148

Many combatants suggested that the job training component of the disarmament programs include a wider range of training options which might offer them better opportunities upon completion. Some DDRR officials in Liberia observed that the preparations for the program lacked sufficient market analysis into what types of employment were needed within the local economy.149

Dr. Francis Kai-Kai, the Executive Director of the Sierra Leonean DDR program, noted the importance of having realistic expectations regarding the pace with which retrained ex-combatants could be absorbed into the war ravaged economy:

Incorporating ex-combatants into the economy was a huge challenge. When we designed the program, it was meant to be linked to the short, medium and long term recovery of Sierra Leone’s economy. While we knew that when the ex-combatants went through the program there was no economy to talk about, we hoped that as it grew, the need for more skilled masons, carpenters, tailors and so on, would grow too. However, in the short term, we wanted to make sure the person had acquired some capacity, albeit limited, so that when they were back in their villages, they would be able to contribute to the immediate rebuilding of their devastated villages, and in the future, have skills to be able to support themselves and their families. We won’t be able to tell how well it has worked until longer term studies are done, but we’re hearing there is a reasonably good degree of success.150

Charles Achodo, from the Liberian DDRR program, stressed the importance of sustained engagement with the ex-combatants even after the reintegration and rehabilitation program was completed. He said such initiatives could complement the job training received through the DDRR program and, in coordination with short and long-term community development initiatives, enhance the ex-combatants possibilities for gainful employment.151 The job training opportunities in the Liberian DDRR program did involve some elements of community development, including efforts to direct food-for-work participants into public works construction, and an increased emphasis on microfinance, especially for women ex-combatants.152 However, job training can best contribute to social stability if complemented by long-term community-based development programs that enhance the ex-combatant’s ability to engage with his or her society.

Several ex-combatants from Sierra Leone went on to fight in the regions’ wars despite having completed skills training and, in some cases, even though they had started to earn a living by their trade. They said the prospect of earning several hundred dollars was too much of a temptation, when compared to toiling at less than one dollar a day.

A military intelligence source with years of experience in West Africa put it this way:

You can have disarmament programs from here to eternity, but if they don’t have jobs, they’ll soon be looking around for another war. Take the ex-combatants in Sierra Leone. They still pose a threat – they are all formed into youth groups which are organized along military lines – many even have long range communication sets. They have no jobs, no economic future, few skills and are angry. Even for those who have been trained, the economy is so bad, there’s nothing to do with the skills they have. They’re just looking around for another war.153

[91] “Sierra Leone Completes Five-Year Disarmament Program”, UN Wire, February 5, 2004 (“Francis Kaikai, the [National Committee for Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration]’s executive secretary, said that after disarming 72,490 fighters and demobilizing 71,043, including 6,845 child soldiers, he was ‘no longer aware of any illegal armed groups posing a threat to the state of Sierra Leone’.”)

[92] Contributions from Member States to the UN regular budget which are determined by reference to a scale of assessments approved by the General Assembly on the basis of advice from the Committee on Contributions.

[93] The World Bank, “Sierra Leone: Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR),” Findings (Good Practice Infobrief), Africa Region, No. 81 (October 2002).

[94] UNDP, “Press Release: Reintegration of former combatants at risk in Liberia”, Monrovia, November 3, 2004.

[95] “Sierra Leone Completes Five-Year Disarmament Program”, UN Wire, February 5, 2004 (“Francis Kaikai, the [National Committee for Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration]’s executive secretary, said that after disarming 72,490 fighters and demobilizing 71,043, including 6,845 child soldiers, he was ‘no longer aware of any illegal armed groups posing a threat to the state of Sierra Leone’.”)

[96] Refugees International, “Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration in Sierra Leone,” August 9, 2002, at 3.

[97] Ibid.

[98] Ibid p 6

[99] Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children, “The Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR) Program,” in Precious Resources: Adolescents in the Reconstruction of Sierra Leone, September 2002.

[100] Liberian Disarmament, Demobilisation, Rehabilitation, and Reintegration Programme: Strategy and Implementation Framework, prepared by the Draft Interim Secretariat, Monrovia, October 31, 2003, at 27.

[101] Ibid, p 28.

[102] Ibid, p 28.

[103] Ibid, p 28.

[104] United Nations Mission in Liberia, “Mission Overview”, page 1 (January 12, 2005).

[105] /Liberian Disarmament, Demobilisation, Rehabilitation, and Reintegration Programme: Strategy and Implementation Framework/, prepared by the Draft Interim Secretariat, page 38 (Monrovia, October 31, 2003).

[106] United Nations Mission in Liberia, “Mission Overview”, page 2 (January 12, 2005). Approximately 10,000 unserviceable weapons were also collected.

[107] Minutes from meeting: “DD Wrap-Up: Key Points Discussed,” Sessions on 8 December 2004 and 19 January 2005, page 1.

[108] Ibid.

[109] Ibid.

[110] Ibid.

[111] Ibid.

[112] Ibid, page 1-2.

[113] Human Rights Watch interview, Bo, Sierra Leone, July 29, 2004.

[114] UNDP, “Press Release: Reintegration of former combatants at risk in Liberia,” Monrovia, November 3, 2004.

[115] Confidential Memorandum to the Under-Secretary General from a Senior UNMIL Staffer, February 4, 2005, pages 2-4.

[116] Human Rights Watch interview with UNICEF protection staff and social workers with child protection agencies, Monrovia, Liberia, August 13-14, 2004.

[117] Human Rights Watch interview, Monrovia, Liberia, August 14, 2004.

[118] See Refugees International, “Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration in Sierra Leone,” August 9, 2002. (“Of particular concern is the fact that the command structure often remains intact in demobilization centers. The US Government is supporting a proposal that would separate commanders from their troops during the demobilization phase by having a separate demobilization camp for commanders, thus weakening the link between commanders and their troops.”)

[119] Human Rights Watch interview, Monrovia, Liberia, August 13, 2004.

[120] Human Rights Watch interviews with UNICEF protection staff and social workers with child protection agencies, Monrovia, Liberia, August 13-14, 2004.

[121] Human Rights Watch interview, Cambridge, May 2, 2005.

[122] Human Rights Watch interviews with social workers from aid agencies, January 24, 2005, February 7 and 15, 2005.

[123] Refugees International, “Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration in Sierra Leone,” August 9, 2002. (“Schools that enroll child ex-combatants have the choice of receiving either educational, teacher or recreational materials. NGOs still need a great deal of support to increase educational opportunities for all children in Sierra Leone. This includes the rehabilitation of infrastructure, more cooperation with the Government of Sierra Leone… and more programs geared towards children, particularly former child combatants, whose schooling was interrupted by the war.”)

[124] Human Rights Watch interview with Charles Achodo, UNDP, via email, February 24, 2005 (“to avoid exposing our staff to possible corrupt inclinations, we contracted out the cash payment for the TSA and subsistence allowance to implementing agencies. This is based on our experience and lessons learned from Sierra Leone.” Also, “Financial management was contracted out to an international management consulting house, Price Water House. Consequently there was clear separation of financial and procurement managment from programming, as well as political and policy process. Also a dynamic and systemic audit was initiated on a regular and frequent basis which helped in forestalling the possibility of management override of internal system of checks and control.”)

[125] Human Rights Watch interviews Sierra Leone, 2000, Liberia, March 2004.

[126] Human Rights Watch interviews, Sierra Leone and Liberia July-August 2004. See also UNMIL, “Second Progress Report of the Secretary General of the United Nations Mission in Liberia” (22nd March 2004), paragraph 56, S/2004/229.

[127] Minutes from meeting: “DD Wrap-Up: Key Points Discussed,” Sessions on 8 December 2004 and 19 January 2005, page, p.2.

[128] Human Rights Watch, interview Kenema, Sierra Leone, July 31, 2004.

[129] Human Rights Watch interview, Monrovia, Liberia, August 14, 2004.

[130] Human Rights Watch interview, Kenma, Sierra Leone, August 10, 2004.

[131] Human Rights Watch interview, Freetown, Sierra Leone, August 17, 2004.

[132] Minutes from meeting: “DD Wrap-Up: Key Points Discussed,” Sessions on 8 December 2004 and 19 January 2005, p.4.

[133] Human Rights Watch interview, Kenema, Sierra Leone, August 17, 2004.

[134] Human Rights Watch interview, Monrovia, Sierra Leone, August 20, 2004.

[135] Human Rights Watch interview, Monrovia, Liberia, August 7, 2004.

[136] Human Rights Watch interview, Bo, Sierra Leone, July 28, 2004.

[137] Human Rights Watch interview, Freetown, Sierra Leone, August 5, 2004.

[138] Human Rights Watch was given a copy of a letter from the ACC to the NCDDR dated June 8, 2004, which referred to a complaint received by ex-combatants for the ‘Omission of Names and Non Payment of Allowance” by DDR. The letter urges the head of DDR to take up the matter, “Since this matter falls outside the commission’s mandate.”

[139] Human Rights Watch interview with Charles Achodo, UNDP, via email, February 24, 2005.

[140] Human Rights Watch interview with Charles Achodo, UNDP, via email, February 24, 2005.

[141] Human Rights Watch interview, UNMIL DDR staff, August 11, 2004.

[142] Confidential Memorandum to the Under-Secretary General from a senior UNMIL staffer, 4 February, 2005, page 7.

[143] Ibid, page 2.

[144] Human Rights Watch interview, Kenema, Sierra Leone, August 10, 2004.

[145] Human Rights Watch interview, Bo, Sierra Leone, July 28, 2004.

[146] Human Rights Watch interview, Freetown, Sierra Leone, August 10, 2004.

[147] Human Rights Watch interview, Freetown, Sierra Leone, August 17, 2004.

[148] Human Rights Watch interview, Bo, Sierra Leone, July 28, 2004.

[149] Minutes from meeting, DD Wrap-Up: Key Points Discussed, Sessions on 8 December 2004 and 19 January 2005, p. 3 (“basic socio-professional survey done at D2 but the operational and political timeframes did not allow for proper assessments”).

[150] Human Rights Watch interview, Freetown, Sierra Leone, August 5, 2004.

[151] Human Rights Watch interview with Charles Achodo, UNDP, via email, February 24, 2005.

[152] United Nations Development Programme, Strategic and Operational Framework of Reintegration Support for Ex-Combatants (3rd Draft for Discussion), pages 24-27.

[153] Human Rights Watch phone interview, May 25, 2004.

| <<previous | index | next>> | April 2005 |