<<previous | index | next>>

III. Police Violence

Violence is a routine part of policing in Papua New Guinea. In interviews with Human Rights Watch, children reported being severely beaten, shot, burned, and cut by police. Children also face rape and other forms of sexual abuse by police. In a number of instances, victims described treatment by police that constitutes torture.60

Although both children and adults who come into contact with police are at risk, children are especially vulnerable. We heard mixed reports about whether police are more likely to use violence against children than adults, but those we interviewed who worked directly with children in conflict with the law told us that they were—that police could more easily intimidate children, that they viewed teenage boys as “raskols,” and that they sought out girls and young women for rape.

A doctor with long-term experience treating detainees and others physically abused by police explained: “It’s the same with adults, but kids are much more vulnerable. They are not able to stand up for themselves. For under-eighteens, police like to bash up first and ask questions later.”61 Staff at a juvenile remand center noted: “The treatment police give boys is different than adults. Because they think a boy will do less against them. So it’s not the same as adults. If they tell him to run, he will run. If they say sit and crawl, he will.”62

The government acknowledged the problem in its report to the Committee on the Rights of the Child in 2002: “Young offenders are often handled roughly. This sometimes involves extreme violence and intimidation by the police and other law-enforcing or prison authorities.”63

Drawing on interviews with dozens of children, this chapter first details the types of police abuse that children face—including beatings, rape, and other serious crimes. It then examines the situation of children particularly vulnerable to such abuse. The final section sets forth applicable legal standards, demonstrating that many children in Papua New Guinea are subjected to torture and other forms of inhumane treatment unambiguously outlawed under both domestic and international law.

Severe Beatings, Shootings, and Other Violence

“The first thing is belting. . . . There are kids, age fourteen and fifteen, here. The police come belt them up. A lot of small kids get belted up.”

“They remove their big police belt or use the gun butt.”

“Or the stick. The truncheon.”

“And the iron.”

“Any iron or stone they see on the ground here, they use it to belt people up.”

—Three men in a Port Moresby urban settlement who had witnessed police beating children, September 16, 2004

The vast majority of children who are arrested are severely beaten by members of the police. Almost everyone Human Rights Watch interviewed in each area we visited who had been arrested was beaten, although our sample was not statistically representative. At every stage in the process, from first contact with police to the police station, severe beatings and other forms of violence are common. Police beat individuals at the moment of arrest, continue to beat them while they are being transported to the station, and often beat them one or more times at the station. Some are beaten on the street and then released. Almost all children we interviewed in every area we visited who had been arrested said that police officers beat them up or worse, regardless of whether they were armed, otherwise resisted, or had surrendered. Children reported being kicked and beaten by gun butts, crowbars (“pins bars”), wooden batons, fists, rubber hoses, and chairs. Many of those we interviewed showed us fresh wounds and scars on their heads, faces, arms, legs, and torsos. Several boys showed us scars they said were from being shot by police. Serious injuries to the face, particularly around the eyes, were common, and one boy told us that police broke his jaw.64

NGOs and medical professionals confirmed that they had attended cases of children badly injured by police upon arrest.65 A doctor with long-term experience treating detainees in Papua New Guinea told us that injuries from police beatings “can range from soft tissue damage to fractures.”66 “I’ve seen evidence of people allegedly assaulted [by police] with gun butts, wooden batons, chairs,” he said. Head injuries were often from:

Gun butts, usually the butt of the rifle or shotgun. If they’re using an assault rifle, it has a metal butt and makes a contused laceration. It takes a long time to heal. . . . In most places the evidence is compelling and consistent. It’s not just the skin that’s broken—you go through layers right to the skull. . . . If it’s a sharp cut, clean, that you can suture—it takes a week to get a good union. But a bash, when the cut is pulverized, it takes weeks because you can’t suture. . . . It leaves a more significant scar, and in the tropics things are likely to get infected.67

Many children described police inflicting severe pain and suffering designed to make them confess to a crime or to punish them for things they may have done. The doctor noted:

In my experience, interviewing and lockup is when most of the damage is done. . . . Broken bones—they used the stools in the police station with metal legs. Severe, sadistic stuff—a group with one person. Supposedly to get kids to give evidence. . . . Prisoners—the amount of damage they already had on their bodies—they said it was during investigation and lock up.68

Some government officials have acknowledged that violence is part of police practices. For example, the police force’s Internal Affairs Directorate acknowledged in a 2004 document that “offenses regularly committed by undisciplined police” include “[e]xcessive and often unprovoked violence when arresting a suspect.”69 The head of criminal investigations for Wewak admitted that police often hit detainees during questioning: “If you cooperate, why should I punch you? Sometimes you’re called in, you blow up . . . . Those that commit crimes will tell lies. That’s when people start getting frustrated, then they try to bash him up, punch him.”70 Later he told us that police guidelines prohibited punching a suspect during questioning and that officers followed the guidelines because the defendant would be asked in court if he were punched or threatened to talk.71 Papua New Guinea’s Evidence Act does provide that confessions induced by threats shall not be received into evidence,72 but, as explained below, this provision appears often not applied.

Children’s Testimonies

Edmund P., age fifteen, said he had been in prison for one week awaiting his next court date when we interviewed him.73 His right eye was completely blackened and the outer half of the white of his right eye was blood red. Along his cheekbone were pink patches of new skin and scabs. He also showed us lumps and healing cuts on his head. Three police officers, armed and in uniform, had arrested him for possessing a gun, he said. Edmund P. described what happened:

The police caught me at a supermarket. I was alone. . . .

They started bashing me up when I was still holding the gun. But after they took the gun away, one policeman kicked me in the head with his boot. This was how I got the black eye.

Then the police hit him with their fists, a piece of wood, and their gun butts, he said.

After they took the gun but while I was still outside the supermarket, one policeman cut my hand with a pocket knife. He was holding my hand tightly when he cut it, but I wasn’t handcuffed. All the policemen were holding me. They were saying things like, “You are the troublemaker.”74

The end of Edmund P.’sleftpinky finger was deeply split, very swollen, and red. According to a pediatrician who viewed photos of the wound, the injury was consistent with an intentional injury.75

Elias C., age twelve, described being arrested in August 2004 for breaking into a horseracing machine, a gambling game. “I put my hands up and surrendered but they belted me up anyway.”76 The police and a local security guard kicked and hit him, he said:

They told me to lie down and they kicked me with their black police boots. I got a black eye. . . . The police hit me on my neck and on the other eye. My neck started bleeding . . . . I couldn’t open my mouth to eat and I still have pain. I can’t open my mouth really wide.77

Then the officers took him to Boroko police station in Port Moresby, he told us:

They put me in a room to make the statement. Then the police just whipped me up with umbrella wire. They hit me all over my face and back. I had whip marks on the sides of my cheeks and my face and my head. They swelled up. There was only one person who whipped me up. The policeman who kicked me earlier was there and the other one was writing my statement. They asked me if I was one of them and I said it wasn’t me.

After they whipped me, they took me back to the cell. I don’t know what the statement said—they didn’t show it to me.78

Carol A.,age seventeen, who was arrested in the 2004 raid on the Three-Mile Guesthouse described in the appendix to this report, told us that the police whipped her with rubber hose, leaving bruises on her back.79 Leilani S., age sixteen, arrested at the same time, said that “the police bashed me with a big stick,” causing her side to swell.80

Kevin B., age fifteen, showed us a thin scar where his left ear attached to his head and scars on the back of his head and told us that three or four policemen arrested him in 2003:

I said I was innocent, but they arrested me anyway. They said, “You are lying and we’ll bash you up.” And they did. They bashed me up and cut up my ear. This was from a big stick—a hard wooden baton. It was about three feet long.81

Then, he said, the officers took him to Waigani police station in Port Moresby, where around five policemen beat him and other detainees in the cell block:

They told me to take my pants off and I was naked. Then they beat me. . . . As they were bashing me up, they kept saying, “lick cunt.” They kept saying these same words over and over again. They were also whipping me with a long rubber hose. . . . They whipped me on the back of my body and the front.

Afterwards, I was bleeding and they told me to shower—to wash the blood off. My hands were really hurting and bleeding because they had bashed them with the rubber hose.82

Yoshida T.,a sixteen-year-old street vendor, told us that the Friday before we interviewed him task force police arrested him for selling at Four-Mile in Port Moresby. One officer “threw me in the car and put his foot on my face. He had on black boots that scratched my face and cut my mouth with my teeth and it bled. I was lying down inside the car and he put his foot on my face. . . . He also punched me in the chest. He was not a small man—he was a big tough man.”83

Yoshidah T. also said that police stopped him and his friends in 2003 and accused them of stealing a bale of secondhand clothes:

They took us up to Touaguba Hill and lined us up and broke new branches from the trees and started beating all the boys up. They told us to stand up one by one and run away. One would stand up, get whipped, and run away. Then the other would come. . . . I had some marks on my head from this—I still have pain in my head. Some of the other boys had scratches and marks on their jaws. Others had scratches on their legs and pains and swollen places where they were hit with the sticks.84

Sydney V.,age sixteen, said that police in East Sepik province beat him in the car on the way to Wewak police station in July 2004: “They used the barrel of the gun on my backside, on my hips, on the side of my hips, on the bone.”85 At Wewak police station, police forced him to remove his shirt and beat him with a fan belt as they interrogated him.86

Amana T., age fifteen, said that police arrested him on September 6, 2004, on his way to school. “They caught me and asked me for the money, and I told them that I had used it already. Then they beat me up. They kicked me with their boots. Three police did this. And they bumped me on a brick wall. . . . They kicked me hard. I was putting my hands like this,” he said, using his hands to shield his face.87

They were kicking my hands, kicking my legs, bouncing me against the brick wall. They kicked my knees and stepped on my toes. . . . I didn’t deny it. I said it was me. They brought me to the station and they belted me again. I think it wasn’t the rule of the policeman. They make their own rules.88

Channel B., age eleven, described what happened when he went to nearby police barracks to buy firecrackers from a police officer’s mother:

There were two policemen who were drunk. . . . They grabbed me on the back of the neck and held me upside down from the collar of my jacket. They started hitting me with a cane. They hit me on the back and legs. . . . Then they threw me head-first onto the ground. They had an M-16 and shot it into the air. They were about fifteen feet away at this point, outside of the barracks. I got up and started running and I ran to my parents.89

His mother said that when she went back to the barracks to complain, “I asked them for compensation and they gave ten kina [U.S.$3.21], a chicken, and a bag of betel nut.”90

Warren V., age fifteen, said he was arrested and taken to Badili police station in Port Moresby in mid-2003. At the station, he said, police began to beat him with an iron bar:

They told me to call out the names of the others when they were belting me up, but I didn’t name anyone. . . . Then they brought some food for me and told me to eat the food. I didn’t want to eat it but they insisted. It was bread and some cordial [soft drink]. They wanted me to eat the food so I would say everything. After I ate, they said, “If you tell us the truth, we will stop belting you up.” There was blood running from my wrist and my legs. . . . They badly bashed me up, so I told them about the charges. But I didn’t speak until they bashed me up.91

Kalan P., age seventeen, explained that his parents took him to a Port Moresby police station around July 2004 after getting word that he was wanted for a robbery. The police took him inside for questioning:

There were two CID [criminal investigation division] officers questioning us . . . in their office. . . . The policeman got an axe and used the dull side and hit me on the forearm and knee. He hit me three times on the arm and once on the knee. They also hit my friend with the axe. They wanted me to tell the true story about the holdup. They were trying to beat us up to make us say, but we couldn’t talk because we didn’t do that thing.92

Kakalem N.,age seventeen, also said that Wewak police beat him with an axe handle on his back and kicked him upon arrest and in the car on the way to the police station.93

Nelson R.told us he was fourteen years old but did not know the year he was born; he looked younger. He said he was arrested the week before for stealing a man’s shoes and taken to Waigani police station in Port Moresby.

There’s a room where they take people for writing reports. It has tables and chairs. . . . There were about seven policemen present. They were from the task force—they had on dark blue uniforms with six pockets. There were three policemen. They pushed me in the back, lifted me up, and threw me down on the floor. They hit me with a stick, and I blocked it with my arm. Blood came out of my head because they threw me head first onto the cement floor. It really hurt. They swore at me, and told me to ““kaikai kan [eat cunt].” They said, “If you get in trouble, you will really feel some pain.” . . .

They took my statement there. I don’t know what the statement said. They didn’t show me. . . . .

I was telling the police, “it’s my first time, don’t beat me up,” but they didn’t listen to me.94

Philip D. said he was arrested in Rabaul, East New Britain, in April 2003. At the station, he told us, “[t]hey beat me up with all sorts of things—a bottle, iron, sticks. . . . In the CID [criminal investigation division] room, when I was sitting there, one policeman turned and punched me and the other one kicked me. Another one beat me with an iron bar to force me to tell what I had done. I am still feeling pain in my ribs because of the kick I received with the boot. . . . They used an iron bar to hit me on the legs.”95 Philip showed us marks on his legs that he said were from where police hit him.

Gabriel R., age twelve, said that task force police beat him with an iron bar in front of his home in June 2004:

They hit me on the face, and I had a swollen face and legs. . . . I was bleeding from my mouth and my nose, and my legs were swollen and they hurt. I couldn’t really walk after that. . . . At my house the police asked me, ‘Did you guys hold up a vehicle?’ I said, “No.”96

Several children told us that police shot them.97 For example, Jackson S., age seventeen, said that four police officers arrested him for robbery on February 13, 2004, at around 10 a.m.: “I was at home when they came in just trying to shoot my legs. My mother just ran down and covered me [so that the police couldn’t shoot me]. They told my parents to take me down to the police car. . . . I pleaded with them to take me to Boroko [police station], but they took me to an unknown place and shot me in both legs. I was shocked to see the holes in my legs. . . . I had heavy bleeding. I almost passed out.”98

Beatings are so routine that police make little or no attempt to hide them, beating children in front of the general public and international observers. In interviews with NGOs, people working within the justice system, and others in Papua New Guinea, many volunteered that they had witnessed police openly beating children on the street and in police stations.99 For example, Sinclair Dinnen described witnessing in Waigani police station in 2004 police beating a screaming thirteen- or fourteen-year-old boy who, he said, was caught stealing clothes from washing lines.100In a group interview in a community in Wewak with around 120 people of all ages, male and female, around one-quarter raised their hands when asked if they had seen with their own eyes the police hit someone.101 Eighteen said they had been personally struck by police.A hospital staff member in East New Britain also described witnessing the police set the public on a handcuffed suspect one morning in mid-2004:

Recently someone held up someone at a store. The police put him in their vehicle and drove him to the back of the cemetery. This was in the back of the children’s ward so we saw it. He was about half a football field away from where I was. It wasn’t far. . . .

He was given to the public to bash. There was a crowd around. He was handcuffed and sitting in the police car and everyone came to give him a blow. Someone got a ripe paw paw and pushed it into his mouth. He was young, maybe seventeen or eighteen. He looked secondary school-age. . . . He had bruises all over his face. Some of his teeth came out. They broke one of his arms. . . .

It was fifteen to thirty minutes that there were people bashing him. Then they [the police] took him to one part of the hospital.102

Human Rights Watch researchers, while interviewing the head of the task force in the Wewak police station, heard the sounds of blows from the room next door. Officers at the station told us that the victim of a theft was beating the person arrested for the crime.

Rape and Sexual Abuse of Girls and Boys

Girls and sometimes boys are vulnerable to sexual abuse by police. In interviews with Human Rights Watch, girls and women told us about rapes, including pack rape, in police stations, vehicles, barracks, and other locations. In some cases, police carried out rapes in front of witnesses. Witnesses described seeing police rape girls and women vaginally and orally, sometimes using objects such as beer bottles. Girls and women who are street vendors, sex workers, and victims reporting crimes to police, as well as boys and men who engage in homosexual conduct, appear to be especially targeted.

Girls

So many women are arrested by police. They end up in jail and have some personal contact with police. I should say rape. We cannot help ourselves. . . . Especially the very young girls. They have to give themselves. It cannot be helped. They are scared. Women are the worst affected by the police.

—Woman detained and sexually harassed by police, Wewak, September 18, 2004

Sexual abuse by police of girls is less visible, and thus less acknowledged, than police beatings of boys. One reason is that few girls and women are charged, prosecuted, and convicted, so the number officially in contact with the justice system appears low. Victims of police abuse, with justification, fear retaliation if they report the abuse. And, as explained below, offenders are rarely disciplined.103 A doctor explained:

It’s hard to get hard proof, but having dealt especially with teenage girls who have been in cells, their accounts of almost ritual abuse in exchange for not pressing charges is a common scenario. If they provide sex, the police let them go home.

It’s almost impossible to get documentary proof because the girls are so scared of retribution. I’ve never known one yet who was willing to write down a statement because of fear of retribution. It’s not just young girls, it’s also women. It seems to have gotten worse in the last ten years, especially in Port Moresby.104

As in many parts of the world, rape and sexual abuse carry stigma for the victim and few services for victims are available; these problems also contribute to abuses going unreported.105 Staff of an NGO that works with sex workers in Port Moresby told us: “If someone is known to sell and they are in custody, they will be raped and nobody is going to talk about it.”106

Given these difficulties, Human Rights Watch did not interview any girls who said they were raped themselves. However, we did interview people who said they witnessed girls’ rapes. We also reviewed written statements made by girls shortly after police raped them and interviewed medical professionals and social workers who had provided professional treatment to victims.

Police often detain girls and women on pretextual grounds, rape them, and release them without ever taking them to the police station; in some cases police demand sex in exchange for release.107 “They never take us to the station and charge us,” explained a nineteen-year-old woman who later said she had witnessed police rape others. “They take us to the bushes and forcefully have sex with us.”108 A policeman in Goroka told an NGO/UNICEF researcher in 2004 that it is common for night duty police to threaten young women in police custody with long prison sentences “unless they agree to let the police take turns having intercourse with them.”109 He also admitted that police often offer lifts to young girls on the roadside and rape them:

In fact we force ourselves on them. Other times we pick up very young girls and buy them beer and then have sex with them. . . . Many policemen think they are above the law when in their uniforms. After I got STI [sexually transmitted infection] I no longer take part in this sexual abuse activity. But the practice continues even now.110

Another policeman in Eastern Highlands Province told the same NGO/UNICEF researcher: “Most policemen in night duties use the women and girls kept in custody for sex. On the pretext of taking their stories they are taken to offices where policemen also have sex with them.”111

Similarly, a staff member of the National AIDS Council who spent four years working with sex workers in Lae confirmed that:

Because of the uniforms, police can do anything with women: line-ups in the cell, line-ups in the vehicle, lines-ups at a common site they take women to. A lot of police say, “If you don’t offer sex, we’ll take you to the cell.” So the women tend to offer sex to avoid this. . . .

“Line-up” means five or six policemen line up on one woman.112

Misibel P. described witnessing police officers rape her sixteen-year-old half-sister in September 2004.113 The Tuesday before we interviewed her, she said, at around 7 p.m., she and her sister were selling betel nut and cigarettes with a group of vendors in Goroka when a police car came and chased them:

We were the unfortunate ones because we got caught. They told us to stop because we were holding betel nut and smokes [which are illegal to sell in Goroka]. . . . They said things like, “pipia meri—you garbage women. Don’t walk around town. Sell your garbage where you live.” . . . They said, “We are going to the station to sort out the problems.”

We were scared so we got into the car, but they never took us to the police station.

After driving around for about an hour, smoking and chewing betel nut, the police took her, her sister, and another woman in her mid-twenties up to a local mountain, Misibel P. said.

Police officers told [the two others] to get out of the vehicles and chose them. Forcefully. Some policemen asked me to have sex but I said, “I have a lot of kids.” . . . [My sister] was a virgin—sixteen years old. She had just had a period one week before. They took her up. The other one was a sex worker. I witnessed it. I saw it a few meters away with my own eyes. I saw everything.

When they finished, they returned our betel nut and smokes because we had sex with them. . . . They let us out at about 8:30.

Now, Misibel P. told us, her sister “just stays in the house”; she is scared to leave the neighborhood and go to town. “After the incident, she had difficulty walking. And she had problems with urination. . . . She wants to take legal action, but she is scared that her older brother would think that it was voluntary. She’s just scared of any male and thinks they might do the same thing.”114

Sharon A.,115 age sixteen, reported that five policemen abducted and raped her in police barracks in Port Moresby on March 15, 2004. In written statement recorded the day after, Sharon A. described what happened:

At 11:00 PM on the 15th March, 2004, I was at the post office walking towards Boroko police station. I was walking with a girl friend of mine by the name of [name withheld]. While we were walking down a mobile [squad] vehicle ten seeter (dark blue) ZGB.826 driven from Boroko police station towards post office (back road). My girl friend saw them and ran away. She was walking at my back so I did not know until the 10 seater [a mobile squad vehicle] stopped in front of me. I was asked to jump in the vehicle. But I refused. But one member came out from the back of the vehicle with a cable wire and belted me twice at my buttock and forced me to jump into the vehicle which I did fearing that they will beat me more. . . .

The vehicle parked at the back of the first mobile [squad] single quarters [at McGregor police station barracks]. . . .

When the vehicle was parked, 4 members got off the vehicle and I was left with the vehicle driver. Driver forced, me to suck his penis and I kept resisting. He forced my head down and I kept pushing my head back up. That was at the back sit of the vehicle. He then forcefully pull my six pocket jeans down and my pants also. I resisted and pulled my jeans up and he kept doing the same thing until I gave up, fearing he might beat me. So he managed to put me down at the back of the vehicle and had sex with me until he released sperm into me. He did that without a condom. He left me and went away. I tried to lift my pants and jean. Another policeman, in uniform came to me and forced me to have sex. He came and put me down and had sex with me. He then left and another came. By the time I was feeling so weak with the force exerted on me. He left and the other two followed. Then all five of them had sex with me.

By then a friend of mine came to my rescue and insisted to take me away. After some argument. He succeeded and got me away to his room until dawn. He escorted me to the bus stop gave me bus fare and left me off and told me not to come back to MacGregor.116

Human Rights Watch interviewed the friend who was with Sharon A. when police officers abducted her. The friend said that she saw police force Sharon A. into the vehicle and that Sharon A. told her shortly afterwards that police raped her.117 An NGO whose staff spoke with a girl and provided her with services in the two days after the incident reported that she told them the same story.118

Other women also described similar incidents. For example, Ehari T., age nineteen, told us that five mobile squad officers abducted her and several other sex workers in Goroka in 2003.119 Sometime before midnight, she said, she and some other women were outside waiting for clients. Police wearing mobile squad uniforms forced them to get into a police vehicle, “for Charlie 12, a ten-seater,” she said, and took them up to “Mountain Kiss.” “The police don’t do anything to me because my brother is on the force,” she told us.

They told me to sit and wait in the car. They had forceful sex with the others. . . . I saw it with my own eyes. They were having intercourse just a few meters from our car. I told [the other girls] to take legal action, and I’m prepared to be a witness. But the girls say they are scared. They know that they will still have to go out at night and will have problems with police.120

Alice O., age nineteen, who also told us that several drunk police officers had tried to rape her the weekend before, described being abused by police when she was around fourteen or fifteen years old.121 The police stopped a truck that Alice O. and five other girls were riding in, she said. “A police car stopped us at the crossing near a bridge on the highlands highway. A cop opened the door. The truck didn’t have a light on. He said, ‘You guys drinking?’ Only one person was drinking.” The officer began beating the driver, she told us. Then,

He told the driver to take off and leave us. The driver said, “I said I would drop them off at the dance.” The cop said, “If you don’t get in the car, we will charge you for drinking in the car.” So he got in.

The cops came and got the girls one by one. There were five guys. There were five girls so they each had one for themselves. One came to me. I was crying and said, “You guys hit me already.” . . . The same guy who hit me wanted to take me out. I said, “You have already belted around so how can I go?” He booted me on the ass and slapped me. He pushed me. I had a lump on my back and bruises on my bum. . . .

After that, they took the other four out. They did whatever they could do with them. . . There was moonlight. It was on the dirt. It was right in front of me. I could see through the window. It was forcible. The others had injuries from where they were belted—they had bruises on their bums and where they were forced to have sex.122

Alice O. did not claim that she was raped.

Like these women and girls, many victims are never taken to the police station and do not show up in the limited records kept there. However, girls and women who are taken to police stations may be raped there as well.123 For example, in Wewak, there are no cells for girls or women, who, the officers there told us, sleep at the front desk or in the courtyard. A woman in Wewak described her arrest in 1997: “I thought they were going to put me in the jail. It was nighttime.” However, she said, she was left to sleep in a hallway at the station. Around 1 a.m., she told us, she felt an officer groping her. He said to her, “‘If you do this to me, I’ll help.’ I said, ‘Are you kidding?’” and he replied, “‘I am trying to help you, if you give yourself to me.’”124

A doctor also confirmed:

In the course of my work, I’ve interviewed girls who said it happened. Both girls in prisons and there in cells or who have come to me afterwards. They would come to me worried about STIs [sexually transmitted infections].

It’s anecdotal, but in many of the cases, the physical findings were totally consistent with both physical and sexual abuse. A lot of the time, for example, proving allegations of oral rape is extremely difficult. Vaginal rape is easier because you can see more trauma. But of those I’ve dealt with, when I’ve examined them, there is evidence that vaginal sexual abuse has occurred.125

A community police officer, the head of a women’s organization, caseworkers for a local NGO, and Sinclair Dinnen also told Human Rights Watch that this was the practice.126

High-level officials are aware that police are raping girls and women in cells.127 Both a 2004 administrative review of the police commissioned by the Minister of Interior and documents provided by the Internal Affairs Directorate in 2004 confirm that police officers have raped women and girls in police stations and cells.128 The head of the sexual offenses squad in Kokopo, East New Britain, considered one of the most effective sexual offenses squads in the country, told us that he had handled two such cases in the last two years: “Females charged, locked up in cells—policemen are entering and sexually abusing girls in custody. . . . There is a separate cell block for women and girls, but policemen use their key. His duty was to look after the cells, and he ended up doing other things instead.”129 As of September 2004, the cases were pending in national court.130

One of the more widely-publicized incidents of police rape occurred on March 12, 2004, when police raided an alleged brothel in Port Moresby, known as the Three-Mile Guesthouse. This case is recounted in detail in the appendix because the abuses were flagrant, because of the large number of victims, and because it illustrates how police actions promote the spread of HIV/AIDS. In addition, because no officers had been punished at the time of writing, despite numerous witnesses and other available evidence, the case illustrates the degree of impunity under which the police force operates.

According to evidence collected by Human Rights Watch, at around 2:30 or 3:00 in the afternoon, police burst into the Three-Mile Guesthouse where a band was playing, rounded up all of the girls and women present, hit them with sticks, bottles, iron bars, gun butts, and rubber hoses, and covered them with food, beer, soft drinks, and betel nut spit.131 One of the women arrested told Human Rights Watch that a police officer “pissed into a half-full beer and made us drink a sip.”132 At least one woman was raped at the guesthouse by several officers. More than twenty girls and women reported that police forced them to chew, and in many cases swallow, condoms. Many were also forced to blow up condoms like balloons and hold them as they were marched through the streets to Boroko police station. Along the way, police and bystanders hit the marchers, threw objects at them, and shouted things such as, “Look! These are the real AIDS carriers!”

Local newspaper and television reporters met them at the station where they were made to sit out front and were lectured by the metropolitan commander about AIDS. Forty-one girls and women were charged with “living on the earnings of prostitution” and locked in cells without food or medical care. That night, police officers took at least four girls out of their cells and raped them. After two nights in detention, the women and girls were released; charges against them were later dropped. The officers involved had faced no sanction for their actions at the time of writing.

Women and girls and NGO staff who work with them also reported that some police officers demand sex when approached for assistance. According to a woman who said she went to the Port Moresby police during a child custody dispute in mid-2004: “The policeman said, ‘I’ll help you but I use you first. If not, it’s your problem.’ I had no choice so I had to give my skin to him.”133 A group of sex workers told us that they couldn’t seek protection from police because “they won’t help us without sex, so we just leave.”134 Staff of the NGO that works with the women confirmed: “They say when there is an issue and they go to the police for help, the police will say, ‘Suck my dick.’ So they won’t go.”135

The head of the sexual offenses squad in Kokopo, East New Britain, described similar cases that he was prosecuting: “These children have come to the police to seek assistance and the policemen turn around and abuse them. These were not family situations—they were involved in official duties.”136

Boys

Boys also reported sexual abuse by police, including anal and oral rape, attempts to force them to have sex with other detainees, and humiliation involving nakedness. Boys are routinely detained with men in police stations and are vulnerable to sexual abuse from other detainees as well.

We heard two rape accounts involving boys, both of whom were picked up by police officers as they left nightclubs that boys and men who engage in homosexual conduct are known to patronize. In one case, which occurred in 2004, a police officer stopped a sixteen-year-old and an adult man when they left a nightclub late at night. The officer ordered the two to perform fellatio on him, the man told us. “I said, well, we have no choice; we just have to do it. My friend did it, and then I took over. It was like, we were taking turns. It was not safe. After that, he told [the sixteen-year-old] to bend over, bend down, and he did what he wanted to with him. He fucked him.”137

A doctor described recently treating similar cases:

Some of the stories I get from young fellows there indicate that quite often if the police pick them up, they sexually abuse them. One guy, about seventeen years old, said he was walking in Boroko in obviously effeminate dress. He claims he was taken into a cell and made to give oral sex to five or six officers until a senior officer walked in. There was no evidence, but I don’t think he was fantasizing. The fear that he felt when he was forced to submit. . . . He talked about his own experience and said it was fairly recent and he was very concerned [about AIDS] because the police had a reputation for being highly sexually active.138

We also heard reports of police beating girls and boys on the genitals and forcing males to have sex with other males in detention. Muna G., around nineteen years old, said police arrested him with a group of about thirteen boys and young men when they were on their way to a birthday party in 1999 and forced them to go to the police station:

We were told to hold each other’s ears. We had to pass by the residences and businesses on the way to the nearest police station, one hundred metres away, still holding each other’s ears. We were told whoever took his hands off would be beaten.

They stood us at the charging table and told us to take off our trousers and put our penises on the table. The police removed their necklaces, the chains that were around their necks, and hit our penises on the table. They struck really hard—they were big chains. . . . They did this one by one. I can’t really recall how long it took. They repeated this. The police went around and around; they beat each of us and came around again. . .

We showed the invite cards to prove [that we were going to a party]. We were going to be charged with loitering, but then someone came in and intervened. He asked them to release us, and we were freed the same night.

They reviewed everyone and sent us out two by two. The youngest, the fifteen-year-old, and the oldest, who was thirty-three, were forced to remain back, and they forced the young bloke, the fifteen-year-old, to [try to] have sex with the older one, anal sex. They told them what to do, but they could not do it, so they only beat them up and sent them off. They had swollen legs and said they had been beaten with sticks. Both were injured on their knees.”139

Similarly, a man in an urban settlement in Port Moresby told us that while he was detained in a police station in 2004, police ordered him to have sex with another man.140

The doctor also described treating “a sixteen or seventeen-year-old boy who they [police] stripped naked, tied him up, had tinned fish smeared on his genitals and the police dogs set on him. There was tremendous damage that took years to repair. Tremendous psychological and physical damage.”141

Most commonly, we heard accounts from boys in which they described instances of sexualized humiliation, such as being forced to run or fight naked, put naked in a cell visible to the public, stripped during interrogation, and ordered to expose themselves to female police officers.142

Menzie M. described being arrested with other boys when he was sixteen or seventeen years old for allegedly stealing a chicken. The police came while they were cooking the chicken under the house, he told us:

They took us to Waigani police station. . . . About eight or nine policemen were there. The police lined up and made us go through them and as we passed through, each belted us up. . . . They used a grass knife, metal, to whip us on the back. They told us to touch our toes and hit us from the legs all the way up. The station commander was there and all the rest were ordinary police. . . . This was inside the police station where they do reports. We were weak because they belted us up.

Then they told us to take our clothes off. . . . They told us to get naked and then to fight. We were scared so we had to follow what he said. They had big iron bars. We fought. Some of us were bleeding. We didn’t want them to hit us again so we had to do what they said. . . . I had bruises on my back. We were all bruised up.143

Menzie M.said he was released the next day without being charged.

These practices appear to be chronic, and we heard cases that went back more than a decade.144

Police Abuse of Especially Vulnerable Persons

Although anyone arrested is at risk of violence, police appear to target those who are the least powerful and most stigmatized, including sex workers, boys and men who engage in homosexual conduct, and street vendors. The illegality of certain acts serves as an excuse to inflict on-the-spot punishment and to deter victims from complaining.

Sex work, which girls reportedly begin as young as twelve or thirteen,145 is not itself illegal, but living on the earnings of prostitution, keeping a brothel, or knowingly allowing one’s premises to be used as a brothelare “summary” (minor)offenses.146 Recent amendments to the Criminal Code exempt children from prostitution charges; however, the Summary Offenses Act, which criminalizes living on the earnings of prostitution, has not been explicitly harmonized with the new law.147 In a 2004 survey of seventy-nine sex workers in Port Moresby, 61 percent reported “police sexual assault/physical abuse” as one of the main problems faced, more than any other response, and that “policemen are the biggest perpetrators of rape and also they never use condoms.”148

Homosexual conduct—described in Papua New Guinea’s law as “carnal knowledge against the order of nature”—is illegal under the Criminal Code.149 A man who described himself as gay and said that police officers had raped him told Human Rights Watch:

A lot of abuse comes from police. They bash us up. They sometimes take us to the station pretending [to question us]. . . . They lock their office. . . . They want a blow job or they say, “I’m going to fuck you”. . . What can we do? They threaten us. They tell us not to shout. They tell us they are going to kill us.150

Street vending was, until 2004, illegal in Port Moresby and other cities. In 2004, the law was changed to allow street vending in restricted areas during certain times.151 Although the law was reportedly intended, among other thing, to address police violence and harassment of street vendors, those whom we interviewed in September 2004 told us that these practices continued. Most told us that police would beat them and destroy their betel nut and other goods, but not formally arrest and charge them. For example, Abraham M., age twelve, told us that he survived by selling on the street small items such as batteries that he buys wholesale. “Sometimes when I’m selling,” he told us, the police “chase me and take the things and belt me up.”152 Ume Wainetti, of Papua New Guinea’sFamily and Sexual Violence Committee, described the impact of police on street vendors:

Those who sell on the streets get chased by the police. Their goods get thrown away or taken away. They have so little that when their goods are taken away, they have no more to go back and buy goods again. They might make eight to ten kina each day, probably enough to buy food for the day.

Police break their Eskis, she said.

An Eski is a cooler. . . . It’s where they keep their ice water, ice blocks. When it’s destroyed, that’s her source of income gone. Or police will destroy the umbrellas that they sit under to sell.153

A 2003 report on women, children, and policing noted a disproportionate impact of the prohibition on street vending on women and girls: “The laws against street vending that are meant to prevent littering discriminate against women whose only means of support is to sell food or betel nut on the street. The ways that NCDC [National Capital District Commission] officers, auxiliary police and regular police deal with women vendors often employ undue force and are a major factor in public hostility towards police.”154

Legal Standards on Torture; Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment; Sexual Violence; and Police Use of Force

Few prohibitions in international human rights law are as unequivocal as the ban on torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment. A large body of international legal authority has developed over the last fifty years that forbids the use of torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment. The prohibition is embodied in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states in article 5: “No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.” That right is reaffirmed in the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment155 and is widely considered a jus cogens norm, that is, a binding and peremptory norm of customary international law from which no derogation is permitted.156

Papua New Guinea is not a party to the Convention against Torture or the ICCPR. It is, however, a party to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which contains a prohibition on torture that mirrors that in both of the previous conventions. The Constitution of Papua New Guinea provides for the rights to life and freedom from inhuman treatment, including torture and treatment “that is cruel or otherwise inhuman, or is inconsistent with respect for the inherent dignity of the human person.”157

The Convention against Torture defines torture as intentional acts by public officials that cause severe physical or mental pain or suffering for the purpose of obtaining information or a confession, or for punishment, intimidation, or discrimination.158 Rape can also be an act of torture.159 The definition of torture in the Convention against Torture is useful in determining the binding content of the prohibition contained in the Convention on the Rights of the Child and in customary international law. A number of the above-described cases fall within this definition and constitute torture.

Article 15 of the Convention against Torture requires states parties to ensure that statements obtained through torture not be used as evidence, except against the person accused of torture.160 This provision prevents police from being rewarded for using torture to extract information. It also is a way of ensuring that children do not incriminate themselves, a protection they have under the Convention on the Rights of the Child as well as the ICCPR.161 Human Rights Watch considers such a rule a central element of the protection from torture as set out in the Convention on the Rights of the Child and customary international law. The law of Papua New Guinea does not specifically address statements obtained through torture, but confessions induced by threats are not admissible as evidence under the Evidence Act.162

In cases where beatings, rape, and humiliation of children by police do not rise to the level of torture, they may nevertheless constitute cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment. Cruel and inhuman treatment includes suffering that lacks one of the elements of torture or that does not reach the intensity of torture.163 Particularly harsh conditions of detention, including deprivation of food, water, and medical treatment, may also constitute inhuman treatment.164 Degrading treatment includes treatment that involves the humiliation of the victim or that is disproportionate to the circumstances of the case.165 For example, in the cases above, forcing boys to fight naked or expose themselves to female police officers violates Papua New Guinea’s obligation to prevent degrading treatment.

Violence in custody by police or other detainees also violates a child's right under the Convention on the Rights of the Child to protection from “all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment or exploitation, including sexual abuse, while in the care of parent(s), legal guardian(s) or any other person who has the care of the child.”166 International law requires that states provide effective remedies for the breach of these principles, including compensation when injuries are inflicted on juveniles.167

By ratifying the U.N. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) in 1995, Papua New Guinea agreed to protect women and girls from sexual and other forms of gender-based violence perpetrated by state agents and private actors alike.168 As a party to CEDAW, Papua New Guinea is obliged “to pursue by all appropriate means and without delay a policy of eliminating discrimination against women” including “any distinction, exclusion or restriction made on the basis of sex which has the purpose of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise by women . . . on a basis of equality of men or women, of human rights and fundamental freedoms.”169 The U.N. Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, established under CEDAW, has noted that “[g]ender-based violence is a form of discrimination which seriously inhibits women's ability to enjoy rights and freedoms on a basis of equality with men.”170 As part of its obligation to prevent violence against women, the government is required to ensure that female victims of violence have access to an effective remedy for the violation of their rights.171 The Convention on the Rights of the Child also establishes girls' right to protection from discrimination based on sex and their right to equal protection before the law.172

In addition to binding treaties on torture; cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment; and gender-based violence, the U.N. has developed detailed principles, minimum rules, and declarations on the actions and use of force by police. The U.N. Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials expressly limits the use of force by police to situations in which it is “strictly necessary and to the extent required for the performance of their duty.”173 Similarly, the U.N.’s Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials states that law enforcement officials, in carrying out their duty, shall, as far as possible, apply non-violent means before resorting to the use of force and firearms.174 When the use of force is unavoidable, law enforcement officials must “(a) exercise restraint in such use and act in proportion to the seriousness of the offence and the legitimate objective to be achieved; (b) minimize damage and injury . . . .; and (c) ensure that assistance and medical aid are rendered to any injured or affected persons at the earliest possible moment.”175 Firearms may only be used in very specific circumstances: “Law enforcement officials shall not use firearms against persons except in self-defence or defence of others against the imminent threat of death or serious injury [or] to prevent the perpetration of a particularly serious crime involving grave threat to life.”176 According to the Basic Principles, “Governments shall ensure that arbitrary or abusive use of force and firearms by law enforcement officials is punished as a criminal offence under their law.”177 Although the Code of Conduct and the Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms are not binding international law, they constitutes authoritative guidance for interpreting international human rights law regarding policing.

The Constitution of Papua New Guinea, as an exception to the prohibition of intentional deprivation of life, permits reasonable force for self defense, to “effect a lawful arrest or to prevent the escape of a person lawfully detained,” to “suppress a riot, and insurrection or a mutiny,” or to prevent a person “from committing an offence.”178 Under Papua New Guinea’s 1977 Arrest Act, police may use all “reasonable means” to make an arrest when a person resists but not “greater force than is reasonable in the circumstances.”179 Similarly, the police have the right to search an arrested person who is in lawful custody but must conduct the search with decency and no greater force than is reasonable.180 The 2004 Juvenile Court Protocol for Magistrates states that police can use physical force on a juvenile only:

- to prevent escape where there is strong evidence that the juvenile may try to escape,

- to protect them from their own actions or actions of others,

- to protect others from the actions of juveniles.181

The police officers Human Rights Watch interviewed in September 2004 did not appear to be familiar with these guidelines. Moreover, the latter exception as written could be broadly interpreted to apply to a large category of children

Assault, homicide, rape, corruption, and certain firearms offenses are crimes under Papua New Guinea law, whether or not the perpetrator is a public official. The penalties are higher when the victim is a child.182

Collective Punishment

Human Rights Watch also documented two cases of collective punishment in Wewak, where we visited the sites of two houses that police had pulled down after arresting a boy or young man in the house for a crime. In one case, we interviewed parents who said that their son, who they said was around eighteen years or younger, was arrested in July 2004 for breaking and entering.183 Early in the morning, the mother told us, four to six police cars came to the house. The provincial police commander, Leo Kabilo, was with them and said to the parents, “Your son has made this crime so you guys are coming down [from the house on stilts] and we’re pulling down the house.” The police tied a rope around the thatch and stick house and used a car to pull it down. Then, the mother told us, “They said, ‘Never rebuild your house. Leave this place.”184 At the time we visited, the family was living underneath a neighbor’s house, waiting for the son’s case to be resolved.

The collective punishment against the family inflicted by the police in this case constitutes arbitrary deprivation of property. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights in article 17 provides that “[n]o one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his property.

Sixteen-year-old boy

who described being beaten by police with a gun butt in 2003. “The police didn’t bash me up easily,” he said.

“They

wanted to beat me until I was dead. Even when I surrendered, I still got hit

on the head.”

© 2004 Zama Coursen-Neff/Human Rights Watch

Fifteen-year-old boy

who said police in Port Moresby beat and cut him in September 2004.

“One

policeman cut my hand with a pocket knife,” he told us.

“He was holding my hand

tightly when he cut it, but I wasn’t handcuffed.

All the policemen were holding

me. They were saying things like, “You are the troublemaker.”

© 2004 Zama Coursen-Neff/Human Rights Watch

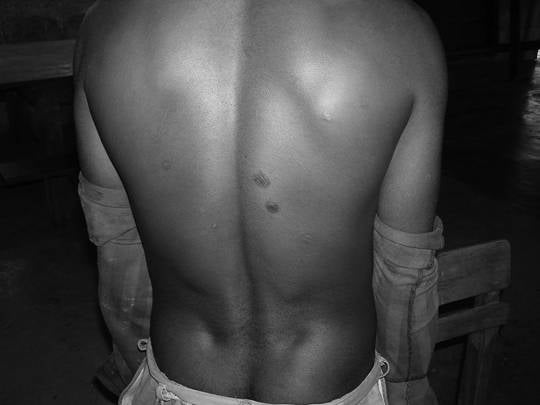

Boy who said he was

shot in the legs by police.

© 2004 Michael

Bochenek/Human Rights Watch

Sixteen-year-old boy

who described being burned by police with sticks of cured tobacco in Wewak

during interrogation.

“When they were burning me, they were saying things like,

‘rotten kids, running around spoiling the place, just another stupid kid in

town.’”

© 2004 Zama Coursen-Neff/Human Rights Watch

Informal market in Port Moresby.

Vendors told Human Rights Watch that police beat them and destroyed their

betel nut and other goods.

© 2004 Zama Coursen-Neff/Human Rights Watch

[60] Convention on the Rights of the Child, art. 37; Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment of Punishment, adopted December 10, 1984, 1465 U.N.T.S. 85 (entered into force June 26, 1987).

[61] Human Rights Watch interview with doctor, Port Moresby, September 20, 2004.

[62] Human Rights Watch interview with staff member of juvenile remand center, September 18, 2004. Similarly, the director of an NGO in Goroka told us, “[y]outh are the most targeted people who get victimized by police brutality . . . because they can’t defend themselves.” Human Rights Watch interview with Noami Yupae, co-coordinator, Eastern Highlands Family Voice Inc., Goroka, September 22, 2004.

[63] Papua New Guinea, “Initial Reports of States Parties Due in 2000,”para. 128.

[64] Human Rights Watch interview with seventeen-year-old boy, Goroka, September 22, 2004.

[65] For example, a staff member of East New Britain Sosel Eksen Komiti (ENBSEK) described attending a case of youth “thirteen to eighteen years old who were released after being badly beaten up. They were bashed up, with broken faces, brutalized. Their faces were totally deformed and disfigured, like a person who goes to war. They were released and then their relatives had to take them to the hospital.” Human Rights Watch interview with staff member, ENBSEK, Kokopo, East New Britain, September 28, 2004.

[66] Human Rights Watch interview with doctor, Port Moresby, September 20, 2004.

[67] Ibid.

[68] Human Rights Watch interview with doctor, Port Moresby, September 20, 2004.

[69] John Maru, Chief Superintendent, Director Internal Affairs, “Discipline: The role of the Internal Affairs Directorate & Discipline Management Issues for Supervisors,” September 5, 2004, sec. 4.2.

[70] Human Rights Watch interview with Edes, head of criminal investigation division, Wewak police station, September 20, 2004.

[71] Ibid.

[72] Evidence Act (1975), § 28.

[73] Human Rights Watch interview with fifteen-year-old boy, Papua New Guinea, October 1, 2004.

[74] Ibid.

[75] Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. Annie Sparrow, pediatrician, New York, January 19, 2005.

[76] Human Rights Watch interview with twelve-year-old boy, Port Moresby, September 16, 2004.

[77] Weeks after the incident, when we interviewed him in detention, he told us, “I still haven’t seen a doctor or a nurse, and I haven’t got any medicine.”

[78] Ibid.

[79] Human Rights Watch interview with seventeen-year-old girl, Port Moresby, September 15, 2004.

[80] Human Rights Watch interview with sixteen-year-old girl, Port Moresby, September 15, 2004.

[81] Human Rights Watch interview with fifteen-year-old boy, Port Moresby, October 1, 2004.

[82] Ibid. Kevin B. showed us the middle finger of his hand, disfigured below the joint, a result of the beating he said.

[83] Human Rights Watch interview with sixteen-year-old boy, Port Moresby, September 16, 2004.

[84] Ibid.

[85] Human Rights Watch interview with sixteen-year-old boy, Wewak, September 19, 2004.

[86] Ibid.

[87] Human Rights Watch interview with fifteen-year-old boy, Port Moresby, September 16, 2004.

[88] Ibid.

[89] Human Rights Watch interview with eleven-year-old boy and his mother, urban settlement, Wewak, September 18, 2004.

[90] Ibid.

[91] Human Rights Watch interview with fifteen-year-old boy, Port Moresby, October 1, 2004.

[92] Human Rights Watch interview with seventeen-year-old boy, Port Moresby, September 16, 2004.

[93] Human Rights Watch interview with seventeen-year-old boy, Wewak, September 19, 2004.

[94] Human Rights Watch interview with fourteen-year-old boy, Port Moresby, September 16, 2004.

[95] Human Rights Watch interview with boy under age eighteen, Wewak, September 19, 2004.

[96] Human Rights Watch interview with twelve-year-old boy, Port Moresby, October 1, 2004.

[97] Police shootings of suspects are also widely reported in the Papua New Guinea press. See, for example, Clifford Faiparik, “City Family Faces a Night of Terror,” The National (Papua New Guinea), April 4, 2005; Daniel Korimbao, “Gang Leader Shot Dead,” The National, May 23, 2005, p. 3; Wanita Wakus, “Cop Shop Raided: Police Retaliate by Shooting Dead a Suspect,” Post-Courier (Papua New Guinea), May 25, 2005; “Suspect Dies in Hospital,” Post-Courier, June 20, 2005, p. 4.

[98] Human Rights Watch interview with seventeen-year-old boy, Port Moresby, September 16, 2004.

[99] For example, a community police officer noted: “I’ve been at the police station quite a while and I’ve seen them bashing little kids—those who were selling things, pickpockets. They hit them like it’s nobody’s business. They can really bleed. Their faces can really change.” Human Rights Watch interviews with a community police officer, Wewak, September 19, 2004.

[100] Human Rights Watch interview with Dinnen, Australian National University, Canberra, October 5, 2004.

[101] Human Rights Watch group interview, community in Wewak, September 18, 2004.

[102] Human Rights Watch interview with hospital employee, village, East New Britain, September 29, 2004.

[103] See Macintyre, “Major Law and Order Issues Affecting Women and Children, Issues in Policing and Judicial Processes,” Gender Analysis . . . , pp. 66-67.

[104] Human Rights Watch interview with doctor with long-term experience treating detainees and others physically abused by police, Port Moresby, September 20, 2004.

[105] See, for example, Garap, “Gender in PNG: Program Context and Points of Entry,” Gender Analysis . . . , p. 7 (regarding lack of services for women and children who are victims of violence and abuse); Macintyre, “Major Law and Order Issues Affecting Women and Children, Issues in Policing and Judicial Processes,” Gender Analysis . . . , pp. 59-69 (regarding the reasons rape is unreported in Papua New Guinea, the effects of rape on victims, the lack of services for women and child victims, and the male-dominated nature of the justice system); and Laura Zimmer, “Sexual Exploitation and Male Dominance in Papua New Guinea,” Point 14: Human Sexuality, 1990.

[106] Human Rights Watch interview with NGO staff member, Port Moresby, September 20, 2004.

[107] An eighteen-year-old woman arrested in the Three-Mile Guesthouse raid told us that during the raid: “One of the policemen went straight to me and said, ‘Let’s go to the room and have sex, and I won’t take you to the station.’ I refused so he took a full beer bottle and hit me on the heel. I am still wounded from this.” Police then arrested the woman and detained her for two nights. Human Rights Watch interview, Port Moresby, September 15, 2004.

A staff member of the Institute for Medical Research, which has conducted research on HIV and run a project for sex workers, confirmed that women had told her of police coercing sex with threats to lock them up in the police station. Human Rights Watch interview with staff member, Institute for Medical Research, Goroka, September 23, 2004. See also Arabena, “Report on the Transex Project,” Appendix 2, “Transex Project Workshops,” p. 27 (explanation of why police are a high risk group for HIV: “They talk about line-ups, hit and runs and they do group sex while they are on the job. When they go out and arrest a woman they say to her they can lock her up or put her in the jail, they say to her if you give us sex we’ll let you go, you know.”); Macintyre, “Major Law and Order Issues Affecting Women and Children, Issues in Policing and Judicial Processes,” Gender Analysis . . . , p. 67; Joseph Anang, Carol Jenkins, and Dorothy Russel, “An innovative intervention research project to encourage police, security men and sex workers in Port Moresby, to practise safer sex,” paper for conference on Resistance to Behavioral Change to Reduce HIV/AIDS Infection in Predominantly Heterosexual Epidemics in Third World Countries, April 28-30, 1999, Australian National University, Canberra Health Transition Centre, National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health.

[108] Human Rights Watch interview with nineteen-year-old woman in group interview with women, Goroka, September 22, 2004.

[109] Help Resources, UNICEF-PNG, “A Situational Analysis of Child Sexual Abuse & the Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children in Papua New Guinea,” p. 48.

[110] Ibid.

[111] Ibid.

[112] Human Rights Watch interview with Wilfred Peters, National AIDS Council, Port Moresby, September 30, 2004.

[113] Human Rights Watch interview with woman around age twenty-five, Goroka, September 22, 2004.

[114] Ibid.

[115] As with all victims of police violence quoted in this report, the girl’s name has been changed.

[116] Signed “Statement of Facts,” recorded by Bomal Gonapa, Policy and Legal Advisor, National AIDS Council, March 16, 2004 (spellings of those of the original document; name withheld, on file with Human Rights Watch). Bomal Gonapa confirmed to Human Rights Watch that he took the statements of girls taken on this date to McGregor Barracks. E-mail to Human Rights Watch from Bomal Gonapa, Policy and Legal Advisor, National AIDS Council, May 5, 2005.

[117] Human Rights Watch interview with eighteen-year-old woman, Port Moresby, September 15, 2004.

[118] “Statement of Facts on Police Raid at 3-Mile Guesthouse 12 March 2004 and related incidents,” signed by Christopher Hersey, Project Manager, Poro Sapot Project, Save the Children in Papua New Guinea, March 20, 2004, p. 3.

[119] Human Rights Watch interview with nineteen-year-old woman, Goroka, September 22, 2004.

[120] Ibid.

[121] Human Rights Watch interview with nineteen-year-old woman, Goroka, September 22, 2004.

[122] Ibid.

[123] See also Anne Borrey, “Ol Kalabus Meri: A Study of Female Prisoners in Papua New Guinea,”Papua New Guinea Law Report Commission, Occasional Paper no. 21, 1992, p. 23.

[124] Human Rights Watch interview, Wewak, September 18, 2004.

[125] Human Rights Watch interview with doctor, Port Moresby, September 20, 2004.

[126] Human Rights Watch interviews with community police officer, Wewak, September 19, 2004; Yupae, Eastern Highlands Family Voice Inc., Goroka, September 22, 2004; Dinnen, Australian National University, Canberra, October 5, 2004. A caseworker whose clients are sex workers reported that:

Sex workers are raped in groups. Police force them to suck their penises. They even fuck their asses, even force them to swallow condoms, even they force them to blow up condoms and march through the streets . . . . They use the barrels of their guns to hit their breasts and vaginas. . . . When they come across a sex worker late at night and if they’re on their own, they beat them up or force them to the police truck. They take them to a remote location and rape them by inserting sticks and other objects into their vagina. They can force them to have sex if they happen to meet a young sex worker with a male client. In Lae, I saw a sex worker who was forced to have sex without a condom with a client. [A police officer] threw the condoms away and forced the worker to have sex without condoms. I brought that case up with the police, but nothing much was done.

Human Rights Watch group interview with NGO caseworkers, Port Moresby, September 15, 2004.

[127] Police rape has also been occasionally reported in Papua New Guinea press. See, for example, Fred Raka, “Kimbe Tense over Rape Incident,” The Independent (Papua New Guinea), June 15, 2000, p. 21 (on-duty mobile squad officers arrested and raped in their quarters a young women in Kimbe, West New Britain province); “Constable Held for Rape of Girl, 16,” Post-Courier (Papua New Guinea), September 9, 1999; “Constable Dismissed, Officer Suspended Over Rape Allegations,” The National (Papua New Guinea), March 16, 2004, p. 2; “Release of Two Cops ‘Surprises’,” Post-Courier, May 5, 2005, p. 7 (magistrate finds insufficient evidence to prosecute policemen accused of raping a women in a police cell in the Southern Highlands).

[128] Institute of National Affairs, Government of Papua New Guinea, Report of the Royal Papua New Guinea Constabulary Administrative Review Committee to the Minister for Internal Security Hon. Bire Kimisopa (hereafter “Kimisopa Report”), September 2004, p. 38; Maru, “Discipline: The role of the Internal Affairs Directorate & Discipline Management Issues for Supervisors,” sec. 4.2.

[129] Human Rights Watch interview with Detective Sergeant Roland T. Funmat, head, Sexual Offenses Squad, Kokopo police station, East New Britain, September 27, 2004.

[130] Ibid.

[131] This section is based on Human Rights Watch interviews with four women and girls arrested in the incident, copies of police records, signed statements the women and girls made shortly after the incident, a written statement prepared by NGO witnesses to some of the events; and interviews with staff of NGOs and the National AIDS Council who interviewed many of the women and girls and who were present at the police station at various points.

[132] Human Rights Watch interview with woman arrested during the Three-Mile Guesthouse raid, Port Moresby, September 15, 2004.

[133] Human Rights Watch interview, Port Moresby, September 15, 2004.

[134] Human Rights Watch group interview with sex workers, Port Moresby, September 15, 2004.

[135] Human Rights Watch interview with Eunice Bruce, World Vision, Port Moresby, September 15, 2004.

[136] Human Rights Watch interview with Funmat, Sexual Offenses Squad, Kokopo police station, East New Britain province, September 27, 2004.

[137] Human Rights Watch interview, Port Moresby, September 29, 2004. Another man in Port Moresby told Human Rights Watch that police beat and raped another boy and him in 1996 when he was sixteen or seventeen. At the end of his account, he described the rape of the other boy, using “she” to refer to the boy:

He was having sex with her repeatedly. She didn’t want to. She was begging for him to stop. She was screaming. But he wouldn’t stop.

The officer punched him before beginning to rape his friend.

I fell on the floor. Then he started getting at [the other boy], tearing her blouse, pulling off the miniskirt she wore. While he was doing it, he was telling me that I’ll be the next one. [The other boy] was begging I was telling him to stop. . . . After that he dropped us off where he picked us up.

Afterwards, he told us, they took down the vehicle’s number plate and went to the station the next day. The police paid him and the other boy one hundred kina (U.S.$32) each. The man said that he had never told anyone what happened:

While they were doing that to me, they told me that I mustn’t raise the matter with the police station. If they see that the matter is reported, they’re going to come back after me and kill me. They were always using threatening words. There aren’t any safe remedies for a gay man.

As a result of that experience, he said,

I never go out all that often. I never go shopping with my family; I never felt freedom. . . . I felt very scared. . . . I felt it was very risky for me. . . . I still feel that way.

Human Rights Watch interview, Port Moresby, September 29, 2004.

[138] Human Rights Watch interview with doctor, Port Moresby, September 20, 2004.

[139] Human Rights Watch interview, Kokopo, East New Britain province, September 28, 2004.

[140] Human Rights Watch group interview, urban settlement, Port Moresby, September 17, 2004.

[141] Human Rights Watch interview with doctor, Port Moresby, September 20, 2004.

[142] Human Rights Watch interview with twenty-one-year-old man, urban settlement, Port Moresby, September 17, 2004 (describing an incident when he was sixteen or seventeen years old in which police arrested him and several other boys, took them to “the area where they do reports” in Waigani police station, and forced them to take off their clothes and fight each other); Human Rights Watch interview with sixteen-year-old boy, September 18, 2004 (describing Wewak police officers forcing him to expose himself to a female officer); Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. Abby McLeod, Australian National University, Canberra, October 5, 2004 (stating that she saw detainees at Waigani police station in Port Moresby put naked into cells visible to the public market).

[143] Human Rights Watch interview with twenty-one-year-old man, Port Moresby, September 17, 2004.

[144] For example, the doctor described a case he had treated some ten years before:

I’ve seen a case of a teenager who . . . was stripped naked and made to masturbate, and they laughed when he couldn’t get an erection. Then they bashed him until they broke his arm and then they made him do it again with the unbroken arm. I didn’t see it, but he told me and the physical evidence of abuse was there. His story is that he was made to do this in front of other people.

Human Rights Watch interview with doctor, Port Moresby, September 20, 2004.

[145] Human Rights Watch interview with staff member, Institute for Medical Research, Goroka, September 23, 2004; Monitoring and Research Branch, National Department of Health . . . , “Qualitative Assessment and Response Report on HIV/AIDS/STI Situation Among Sex Workers and their Clients in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea.” For more information about commercial sexual exploitation of children in Papua New Guinea, see Help Resources and UNICEF-PNG, “A Situational Analysis of Child Sexual Abuse & the Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children in Papua New Guinea”; for more information about sex work generally in Papua New Guinea, see Macintyre, “Major Law and Order Issues Affecting Women and Children, Issues in Policing and Judicial Processes,” Gender Analysis . . . , pp. 64-65.

[146] Summary Offences Act (1977), consolidated to No. 16 of 1993, §§ 55-57. Under section 55, “A person who knowingly lives wholly or in part on the earnings of prostitution is guilty of an offence,” punishable by a fine up to K 400 (U.S.$128) or up to one year’s imprisonment. It is considered prima facie evidence of the offense if a person “lives with, or is constantly in the company of a prostitute” or “exercises[s] some degree of control or influence over the movements of a prostitute in such a manner as to show that person is assisting her to commit prostitution.”

[147] Criminal Code (Sexual Offences and Crimes Against Children Act) (2002), §§ 229(K), (L), (Q).

[148] Monitoring and Research Branch, National Department of Health . . . , “Qualitative Assessment and Response Report on HIV/AIDS/STI Situation Among Sex Workers and their Clients in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea,” pp. 27-2, 328.

[149] Criminal Code, § 210.

[150] Human Rights Watch interview, Port Moresby, September 29, 2004.

[151] Informal Sector Development and Control Act (2004). As of July 13, 2005, according to news reports, informal sector vendors in Port Moresby were restricted to thirteen approved cites and specifically excluded from “all public bus stops, shot fronts, the Port Moresby General Hospital, urban clinics, schools and tertiary institutions, all public roads, car parks, traffic islands and road reserves, including Ela Beath, airports and seaports and all night clubs and hotels.” Penalties imposed by National Capital District Officers and police include removal and a fine. Bonny Bonsella, “Vendors Given Till Monday to Shift to Designated Spots,” The National (Papua New Guinea), July 6, 2005, p. 6. See also Post-Courier (Papua New Guinea), May 20, 2005, p. 6; “City Hall Moves on NCD Markets,” Post-Courier, July 11, 2005, http://www.postcourier.com.pg/20050711/mohome.htm (retrieved July 11, 2005); and Wanita Wakus, “Police Won’t Enforce Law, Says City Manager,” Post-Courier, April 20, 2005, p. 3. Elsewhere at the time of writing, there was ongoing debate about the restrictions placed on vendors. See, for example, “CIMC Condemns Town Authority,” The National, April 22, 2005, p. 8; “‘Oily Bath’ Condemed,” Post-Courier, April 20, 2005, p. 3 (quoting Mt. Hagen City Manager Pious Pim as stating that street vendors were being dipped in oil-tainted water “as a control measure”); “Hagen Leader Wants Changes to Informal Sector Law,” The National, May 11, 2005; “Informal Sector in Be Made Aware.”

[152] Human Rights Watch interview with twelve-year-old boy, urban settlement, Port Moresby, September 16, 2004.

[153] Human Rights Watch interview with Ume Wainetti, Family and Sexual Violence Committee, Port Moresby, September 15, 2004.

[154] Macintyre, “Major Law and Order Issues Affecting Women and Children, Issues in Policing and Judicial Processes,” Gender Analysis . . . , p. 63. See also Wayne Stringer, East Sepik Council of Women, “Submission to PNG Police Review,” 2004 (reserve and auxiliary officers victimize street vendors).