<<previous | index | next>>

IV. Physical Abuse and Ill-Treatment of ISA Detainees in Kamunting Detention Center

The Malaysian government continues to bar international and Malaysian human rights groups from visiting Kamunting. Consequently, descriptions about conditions in Kamunting come from detainees, their families, detainees’ lawyers, who have limited physical access to the facility, and the Human Rights Commission of Malaysia, SUHAKAM.

According to the 2003 Suhakam report on conditions of detention under the ISA, most ISA detainees in Kamunting live in dormitory style blocks, which are surrounded by a grassy compound. The detainees are allowed to move within designated areas of the compound. 25

Detainees accused of similar offenses are housed together. Each cell block is numbered. In 2003, detainees were allowed restricted access to newspapers and books.26 They were allowed one visit a week from relatives lasting no more than thirty minutes and with no more than two persons at a time. The visiting rooms were divided with wire mesh barriers separating the detainee and the visitor. Visitors were allowed to bring in only fruit for the detainees and a certain number of books per visit.27

Suhakam recommended amendment of the rules to enable detainees to spend more time with their families.28 Suhakam recommended that detainees should not be physically separated from their families by a wire mesh barrier and that prison officials need not be present during family visits because ISA rules permit authorities to search visitors.29

In mid-2004, amid increased scrutiny of the treatment of ISA detainees in Police Remand Centers and growing pressure from detainees and their families, conditions in Kamunting were relaxed. Detainees’ cell blocks, which normally were open from 7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m., would instead close at 10:00 p.m.30 Detainees could visit different cell blocks.31 Wire mesh partitions in visiting rooms were removed and detainees and their families were allowed physical contact and to visit for more than an hour. Families were also permitted to bring food for their husbands on special occasions. Detainees were also allowed to make handicrafts, which their families sold to the public.32

In early December 2004, a new director, Yasuhimi bin Yusoff, was appointed at Kamunting. According to detainees’ families, the new director began to limit the detainees’ new privileges, which had been negotiated with the previous director. Human Rights Watch recognizes that the inspection of detainee cells and the maintenance of security are legitimate procedures in any detention facility.

The December 2004 Incident at Kamunting

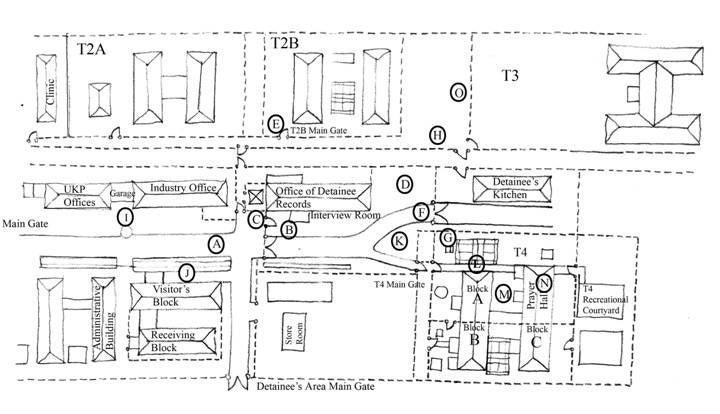

The events of December 8 and 9 involved detainees in cell blocks T2B and T4, which house detainees alleged to be members of Jemmah Islamiyah. (See the following page for a drawing of the facility by an ISA detainee at Kamunting Detention Center; the drawing identifies the location of cell blocks T1, T2, T3, and T4, and marks the locations of events on December 8 and 9, 2004. The map was re-drawn by Human Rights Watch for the purposes of formatting and translation. A copy of the original map in Malay is at Appendix A).

Drawing of Kamunting Detention Center by ISA Detainee Identifying

Location of Events (A-O) on December 8 and 9, 2004 (English Translation)

A. Location where handcuffed T2B detainees were beaten.

B. Location of Shukry Omar Talib [ISA detainee] during the beatings.

C. Location where Shukry Omar Talib discussed with Kamunting director after the incident at T2B.

D. Location where Shukry Omar Talib and Zid Sharani [ISA detainee] witnessed the T2B incident.

E. Location of 70+ UKP (Unit Keselmatan Penjara, prison security unit) officers before raid on T2B.

F. Location of Shukry Omar Talib’s discussion with Ahmad Yani after Shukry’s discussion with the Director.

G. Section of wall that was detached by T4 residents.

H. Chain-link fencing.

I. Federal Reserve Unit (FRU) gathered here.

J. UKP officers resting place after T2B operation.

K. Assembly of FRU & UKP officers before entering T4 on December 8, 2004.

L. Path where T4 detainees were beaten by the UKP and Kamunting officers.

M. Second body search performed here.

N. Block where T4 detainees were handcuffed, forced to sit on the floor, and beaten.

O. Several parts of wall removed to witness T2B incident.

The Raid at Cell Block T2B

On December 8, prison officials conducted an unannounced inspection of cell block T2B, which housed mainly Indonesians, Filipinos, and a few Malaysians. According to eyewitnesses, on December 8 at 9:00 a.m., fifty to sixty guards (Unit Keselmatan Penjara or UKP) (prison security unit) armed with shields, batons, and riot gear entered block T2B.33 Deputy Internal Security Minister Datuk Noh Omar, as reported in the Malaysian press, claimed that detainees on December 8 tried to prevent spot checks of cells and set off a riot.34 The minister said that detainees blocked the entrance of T2B and, when officers forced open the gate, threw stones and other objects at them.35

Detainees say that, through a hole in the wall separating block T2B and T4, they saw handcuffed detainees beaten by UKP officers as they were brought out from T2B.36 Ahmed Yani bin Ismail, observing through the hole, later wrote, “I saw Sulaiman Suramin brought out of T2B handcuffed from behind by several UKP officers. He looked weak—limp. He was then followed by other residents of T2B. I saw Zulkifi [Deny Ofresio]37 and Ibrahim [Ibrahim Ali] with their clothes soaked with blood. I also saw a warden punching and kicking Zulkifli when he was taken, handcuffed from behind, by the UKP.38

Another detainee wrote, “Not long after the UKP officers stormed inside T2B I saw as many as twelve detainees brought out from T2B in a weak state, bleeding from their heads, their clothes dirtied, and handcuffed from behind.”39

Mohamad Zamri Sukirman, another eyewitness to the events on December 8, wrote:

On December 8, 2004, around 10:40 a.m., several detainees and I were in the detainees’ kitchen area. I was there to see more clearly what was happening to T2B residents with the UKP. I saw T2B residents brought out from their area handcuffed and escorted by two UKP officers. . . . I saw several UKP guards standing in [another block] head towards them. They began kicking and beating them.40

The detainees’ lawyers, who saw their clients on December 28, told Human Rights Watch of several assaults. Zaini Zakaria, in detention since 2002, from cell block T2B, reportedly was handcuffed and hit on the back of his head with a metal rod by a guard, which resulted in him receiving twenty stitches.41 Sulaiman Suramin, in detention since 2003, had some of his fingers broken after prison guards stepped on them. Ibrahim Ali, in detention since 2003 and released in July 2005, was beaten, which resulted in him receiving six stitches to his head. Zakaria bin Samad was kicked and beaten as well.42

Two other detainees from T2B suffered from broken bones—Abdullah Zaini, an Indonesian, had a broken hand, and Sofian Salih, a Filipino, had a fractured leg.43

In total, eight guards and twelve detainees were reportedly injured on December 8. It is difficult to assess the intensity of the fight, because no details regarding the injuries suffered by the guards have been made public. As noted above, Human Rights Watch request to interview Kamunting Detention Center Director Mr. Yasuhimi bin Yusoff or a Malaysian government official knowledgeable about the events of December 2004 was unanswered and requests to visit the detention center were denied.

Datuk Noh Omar announced that during spot check prison officials had found knives, scissors, metal rods, and badminton rackets sharpened into weapons.44 The guards also allegedly discovered mobile phones, a charger, and a SIM card.45 The government, as reported in the Malaysian press, claimed that lax security led to the acquisition of these items.46 The detainees, however, contend that the knives, scissors, and badminton rackets had been approved by Kamunting authorities for use in fashioning arts and crafts or for use in exercise and that they been no reports of these items being misused prior to the confrontation.47

The Raid on Cell Block T4

After the raid on cell block T2B, prison personnel informed residents of the T4 cell blocks, which housed Malaysians, that their cells would be inspected on December 8. According to the detainees, they cooperated with the authorities and did not obstruct the inspection.48 Prison officials seized metal spoons, can openers, scissors, paper cutters, cigarettes, wire, metal ladles, a garden hoe, shaving blades, badminton rackets, and a wooden mop and broom.49 Detainees and their families contend that prison authorities had approved these items and allowed them to use knives and scissors to make handicrafts—pencil and jewelry cases and tissue boxes—which their families sold to the public.50 The detainees said that badminton rackets were used by the detainees for recreation and had also been approved by Kamunting officials.51

The wives of three detainees beaten on December 9 claim that their husbands were targeted because they had been “vocal” about their rights in detention and had written to their attorneys, NGOs, Suhakam, and the press.52 Others told Human Rights Watch that their husbands were targeted because they had told their attorneys and the press about torture and ill-treatment in Police Remand Centers, and had made comparisons to mistreatment of detainees in Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison.53

On December 9, according to T4 detainees, UKP officers equipped with shields and batons raided their cells for a second time on December 9 at 4:00 p.m. Twenty-three detainees were ordered out of their cells, handcuffed, and instructed to bend down to their waist and walk in a single file to the prayer room. Detainees consistently describe that despite their cooperation they were beaten, kicked, spat on, and verbally abused.

Mohidin bin Shari, detained since December 2002, wrote that even though he cooperated with the UKP, he was beaten:

My block was opened . . . and we were ordered to exit one by one for body searches. I was the first person to exit. . . . At that time I was inspected by as many as five UKP officers . . . one of the UKP officer snarled at me and said, “Don’t fight. Follow my orders.” I was shocked because I wasn’t putting up a fight at all. My hands were then handcuffed as the UKP officer searched my entire body, groped me, and used a metal detector. After searching my body, two UKP officers whose faces I could not see because my head was bowed and I was handcuffed. . . . . they pressed my neck until I felt pain. I said, “Please don’t press against my neck because it is painful,” but the UKP officers ignored my words.

Throughout the trip towards [another cell block], the UKP that were standing along the path beat me with batons on my head and back. Some also kicked my private parts and punched my head. After reaching the [cell block], they searched my body again. A UKP officer spat in my face. After that, an officer grabbed my hair and said, “What’s with this face of yours?”54

Abdul Rashid bin Anwarul, detained since January 2002, described how he was treated:

They conducted a body search on me by opening my trousers and inspecting my entire body. Afterwards, they handcuffed my hands and I was ordered to bend down. . . . I could not see in front of me as a result of the pressure they put on my neck and my head was hit hard every time I tried to look in front. . . . My back was hit hard . . . causing me to shout in pain. My buttocks were kicked three times nearly kicking my penis. My head and neck was hit and punched numerous times. My right shoulder was hit with a baton causing swelling in that area. My waist was punched which caused it to swell. I was verbally abused during the journey. My right leg was kicked in the shin.55

Ahmed Yani Ismail, detained since December 2001, was kicked, punched, and slapped. He wrote:

Several guards . . . kicked my buttocks eight times, kicked my stomach once, hit the back of my head several times, kicked my back four times, kicked my left thigh once and the area above my knee once. The warden . . . slapped my face in the eye area at least three times. . . . I experienced shortness of breath, nausea for four days, pain in my chest, bruising and pain throughout my body. . . . My mouth bled.56

Yazid Sufaat, detained since December 2001, was hit and spat on. He wrote:

One after the other we were handcuffed, hit with batons, spat on, punched, kicked, and trampled on while brought into the prayer hall. I was able to see this because I was the last person who was brought out. . . . I was handcuffed in the back, they spat on me, stepped on my toes, hit my head, and punched my ribs. I was hauled roughly to the prayer hall by one of the prison guards.57

Zainun Rasyhid, detained since December 2002, wrote:

I was handcuffed and one of them strongly pinched the nape of my neck from behind until it hurt. . . . I was spat on, hit, and punched in my head time and time again. My legs were kicked from behind. . . . While I was at the back of [a cell block], I was searched again and they pulled at my pants until my pants fell to the ground and I was exposed. In this state they forced me to enter [a cell] by kicking me . . . I was ordered to sit cross-legged with my head close to the wall. . . . Not long after two to three guards came and spat on my head, hit my hand, and kicked my back.58

Abdullah bin Mohamed Nor, detained since December 2002, wrote, “My legs were kicked and stepped on while the search was made. . . my back was kicked. . . . The UKP beat my head and body repeatedly with batons and ordered me not to look around. . . I was ordered to sit facing the wall. They pushed my head and it hit the wall. . . . We were treated like animals.”59

Mat Sah bin Mohamad Satray, detained since April 2002, described his experience:

I was flung hard on the cement floor and they pressed their knees on the back of my neck until I felt immense pain, and until my left check was pressed against the dirty cement floor. I was then pulled back up and pushed roughly into the prayer hall while handcuffed . . . My right ribs were flung hard on the floor until I felt short of breath and my cheek was on the floor. After that I was ordered to rise and the handcuffs were moved from the back to the front. I was ordered to sit cross-legged facing the wall and my head was hit against the wall.60

Some ISA detainees in Kamunting reported being humiliated. “I was forced to strip naked and ordered to crawl while returning to my cell,” wrote Mohamad Faiq Hafidh, who has been detained since January 2002.61 Yazid Sufaat says he was ordered to strip naked in front of guards and saw others similarly mistreated. He wrote, “Because I was one of the first people brought to T1, I could witness how some of my friends were beaten up . . . Abdul Nassir bin Anwarul was stripped naked and ordered to crawl and then was kicked in the buttocks.”62

Abdul Murad bin Sudin, detained since October 2002, wrote,

I was roughly searched . . . by the wardens who hit and kicked me and finally I was stripped naked. While being stripped naked, I repeatedly begged that my underwear not be removed. After stripping and inspecting me, they ordered me inside the jail cell by crawling; while crawling in a nude state inside the cell, they then kicked me from behind until I fell, sprawled and the gate of the cell was locked. 63

One detainee’s wife told Human Rights Watch that when she visited her husband a few days after the incident she was harassed by Kamunting officials. “The officials showed me some bras and underwear. They claimed they found them in my husband’s cell and asked me to identify which ones were mine. I was embarrassed. But this was just another way to humiliate us.”64

Sixteen detainees from T4B were then locked inside two blocks for four days until December 13, 2004, and were given insufficient drinking water, no change of clothes, and no reading material except for a copy of the Quran.65

International law widely prohibits torture and all cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment. States are obliged to investigate all credible reports of torture and inhuman treatment. Article 5 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights prohibits torture and other forms of mistreatment.66 The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (the Convention against Torture) reaffirm this prohibition.67 The ICCPR also mandates that persons in detention must “be treated with humanity and with respect for the inherent dignity of the human person.”68 Although Malaysia is not a party to the ICCPR or the Convention against Torture, the ban on torture and other mistreatment is a fundamental principle of customary international law that applies at all times and in all circumstances.

Denial of Immediate Medical Assistance and Access to Counsel

Detainees injured on December 8 and 9 were denied immediate medical assistance. Mohamad Faiq bin Hafidh whose left eye was bleeding due to injuries he suffered on December 9 wrote, “I only received eye wash treatment on Sunday, December 12, 2004. I was given full treatment on Monday, December 13, 2004.”69 Mohamad Faiq bin Hafidh’s wife corroborated the eye injury and told Human Rights Watch, “I was shocked to see [him] on December 11. He had bruises on his face and his left eye was swollen and still bleeding. I put a small towel on his eye.”70

Mat Sah bin Mohamad Satray had a fractured rib as the result of being beaten on December 9. He was not taken to the hospital until December 13, 2004.71

Abdul Murad Samad wrote that he was not given medical treatment until December 13, 2004, when he was taken to the medical assistant at the detention center, who then referred him to the Taiping Hospital.72 He wrote, “My injured eye was washed and I was given medication. My back was hurting and I was given painkillers and my ribs were x-rayed.”73

In a letter signed by twenty-three detainees to the Internal Security Minister, detainees wrote, “The earliest any of us were brought to the hospital was on the third day of the incident, on Saturday afternoon. Some were also brought to the hospital on the eighth day. Many were taken to the hospital after the bruises and marks of abuse were gone.”74

The wives of three detainees beaten on December 9 told Human Rights Watch that Taiping Hospital, where their husbands were treated, refused to give them copies of their husbands’ medical reports.75

The detainees’ lawyers’ requests to meet their clients on December 10 were denied by Kamunting officials on the grounds that Suhakam had scheduled a visit.76 A subsequent request was granted and the lawyers met their clients on December 28, 2004.

Punishment

Twelve T2B detainees and eight of the T4B detainees were singled out and punished for the events on December 8-9, 2004. The T2B detainees are housed separately in Tempat Penerimaan (intake cells), which are used when detainees initially arrive at the camp, and also serve as punishment cells. As of September 2005, three of them remain in solitary confinement.77 According to the detainees’ lawyers, the detainees are allowed out of the cell only from 7:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. They are not provided a bed or mattress, but instead sleep on cement floors. The cells have no light, but only an air vent (1 x 2 feet) with metal bars.78

Eight detainees from T4 block are housed in individual cell blocks and not in a dormitory like the rest of the ISA detainees. According to the lawyers of the detainees, these eight are branded as the vocal group because they voiced their concerns to prison officers, lawyers, SUHAKAM, and the press.79 They are handcuffed when taken to a medical assistant or when prison officials meet with them.80

Such punishment of the detainees violates the Internal Security Act (Detained Persons) Rules, which allow for punishment for five days for minor offenses and seven days for aggravated offenses and only upon a factual inquiry.81 According to the lawyer for the detainees, no such inquiry was conducted before these detainees were punished.82

Restrictions on Family Visits Reimposed

A wife of a detainee, who has been in detention since 2003, told Human Rights Watch:

When we used to visit him before the incident, we, the children and I, could touch him, and sit together in the visiting room. When he was brought to the room, the children would run out and meet him in the corridor and he would come into the room with our son on his shoulders. That would make him happy, but now it’s different.83

She continued that prison officials are now present in the visiting room and “monitor what my husband says to me.”84

Another wife, whose husband has been detained since 2002, explained:

I was surprised when I first saw the visiting room in January 2005. There was a wire mesh and fiberglass partition separating us. Why should he be treated this way? We are no longer allowed to do salam (shake hands). My son is very upset that he can no longer hug his father. The only way to communicate is through a hole located at the bottom of the partition, which is 3-4 feet above ground level and is the size of a 50 sen coin. We have to bend down to talk through this hole. There is no intercom connecting the partitioned area. It is very difficult to hear what my husband says.85

In explaining the size of the holes in the partition, another ISA detainee’s wife, whose husband has been detained since 2002, explained, “I can put my two fingers through the hole. I have to bend really low so I can talk through the hole. This is very difficult. I cannot hear my husband very clearly.”86

Abdul Murad bin Sudin, who has been detained since October 2002, described his December 26, 2004, visit with his wife and children: “During the forty-five minute visit I was not allowed to directly meet them. The room was fenced with . . . wire and obstructed by fiberglass with holes as big as my index finger. I could only touch my children and wife through a finger that was thrust into that hole.” 87

A wife of a detainee, whose husband has been detained since 2001, told Human Rights Watch, “My husband does not know when he will be released. He and others tried hard to convince the officials to allow us better family visits. He was not asking for much. Now that too has been denied.”88

The new restrictions have decreased the frequency that detainees’ families, who have to travel long distances for visits, often at great expense, can visit. One detainee’s wife who lives far from Kamunting and finds it expensive to travel complained that prior to December 2004 she was able to visit her husband two consecutive days a week, but now things have changed. “Before the riot I could visit my husband both Saturday and Sunday. Now if I visit on Saturday I cannot visit him on Sunday, but have to wait till the following weekend.”89

Failure to Investigate

Wives of some of the detainees filed complaints with the police on December 11 and 18, 2004, with the Taiping Police Station, and filed a complaint with Suhakam on December 15, 2004. Detainees also filed complaints on December 21, 2004.90 According to the lawyer for some of the detainees, the findings of any official investigation have not been made public and to date no personnel involved in the abuse of detainees have been disciplined or charged.91

The Human Rights Commission of Malaysia, Suhakam, reacted quickly, visiting Kamunting on December 11, 2004. However, for unspecified reasons, to date it has not published its findings. It is not clear if or how it communicated its findings to the government or if it has advocated for prosecutions or disciplinary action against those responsible for abuses.

[25] Suhakam, Report of the Public Inquiry into the Conditions of Detention Under the Internal Security Act 1960, (2003), pp. 25-26.

[26] Ibid., p. 26.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid., p. 37.

[29] Ibid., p. 38.

[30] Human Rights Watch interview with wives of detainees (names withheld), Kuala Lumpur, July 2, 2005.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Memorandum of Protest of KEMTA’s Excessive Use of Force Towards Detainees on December 8 and 9, 2004, to the Minister of Internal Security, dated December 22, 2004, signed by twenty-three detainees from block T4 (KEMTA Protest Letter), copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[34] Leslie Lau, “Weapons Cache in Detention Camp in Perak,” The Strait Times, December 11, 2004.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid.

[37] According to the attorney for some ISA detainees, Zulkifi is the Malay name for Deny Ofresio. Email correspondence from Edmund Bon to Human Rights Watch, August 2, 2005.

[38] Handwritten statement of Ahmed Yani Bin Ismail, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[39] Handwritten statement of Mohamad Khidar bin Kadran, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[40] Handwritten statement of Mohamad Zamri Sukirman, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[41] Email from Edmund Bon to Human Rights Watch, July 29, 2005.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Eddie Chua, “Family Members Claims ISA Detainees Assaulted,” Sunday Malay Mail, December 12, 2004.

[45] Lau, “Weapons Cache in Detention Camp in Perak,” The Strait Times.

[46] “Jamaah Islamiyah Detainees’ Possession of Weapons Shows Lax Malaysian Security,” BBC Monitoring Asia Pacific, December 12, 2004 (citing Malaysian newspaper Berita Harian web site in Malay, December 11, 2004).

[47] KEMTA Protest Letter.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Ibid. Human Rights Watch interview with wives of detainees (names withheld), Kuala Lumpur, July 2, 2005.

[51] Ibid.

[52] Human Rights Watch interview with wives of three detainees (names withheld), Kuala Lumpur, July 2, 2005, and July 5, 2005. The wives told Human Rights Watch that photographs of their husbands were circulated amongst the prison personnel prior to the December 8, 2005. Yazid Sufaat and Ahmad Yani Ismail similarly allege, in their handwritten statements, that their photographs were disseminated amongst the prison personnel prior to December 8. Handwritten statements of Ahmad Yani Ismail and Yazid Sufaat, copies on file with Human Rights Watch.

[53] Human Rights Watch interview with wives of two detainees (names withheld), Kuala Lumpur, July 2, 2005.

[54] Handwritten statement of Mohidin bin Shari, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[55] Handwritten statement of Abdul Rashid bin Anwarul, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[56] Handwritten statement of Ahmad Yani Ismail, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[57] Handwritten statement of Yazid Sufaat, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[58] Handwritten statement of Zainun Rasyhid, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[59] Handwritten statement of Abdullah bin Mohamed Nor, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[60] Handwritten statement of Mat Sah bin Mohamad Satray, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[61] Handwritten statement by Mohamad Faiq bin Hafidh, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[62] Handwritten statement of Yazid Sufaat, copy on file with Human Rights Watch. These allegations are consistent with claims previously made by other ISA detainees. Detainees held in Police Remand Centers alleged that they were forced to strip naked before questioning began, forced to urinate in front of the interrogators, forced to masturbate, and asked questions about detainees’ sex life and adequacy of their sexual performance. See Human Rights Watch, In the Name of Security, pp. 26-27.

[63] Handwritten statement of Abdul Murad bin Sudin, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[64] Human Rights Watch interview with wife of detainee (name withheld), Kuala Lumpur, July 2, 2005.

[65] KEMTA Protest Letter.

[66] Universal Declaration of Human Rights, art. 5, U.N. General Assembly Resolution 217A (III), December 10, 1948.

[67] ICCPR, December 16, 1966, 999 U.N.T.S. 171, art. 7; Convention Against Torture, art. 3, December 10, 1984, 1465 U.N.T.S. 85. The United Nations Body of Principles for the Protection of all Persons Under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment similarly prohibits torture, cruel, inhuman degrading treatment of punishment. U.N. General Assembly Resolution 43/173 (1988), principle 6.

[68] ICCPR, art. 10.

[69] Handwritten statement of Mohamad Faiq Hafidh, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[70] Human Rights Watch interview with wife of detainee (name withheld), Kuala Lumpur, July 2, 2005.

[71] Handwritten statement of Mat Sah bin Mohamad Satray, copy on file with Human Rights Watch. Human Rights Watch interview with family member of detainee (name withheld), Kuala Lumpur, July 2, 2005.

[72] Handwritten statement of Abdul Murad bin Sudin, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[73] Ibid.

[74] KEMTA Protest Letter.

[75] Human Rights Watch interview with detainees’ wives (names withheld), Kula Lumpur, July 2, 2005.

[76] Email from Edmund Bon to Human Rights Watch, August 5, 2005.

[77] Human Rights Watch interview with Edmund Bon, Kuala Lumpur, July 3, 2005.

[78] Ibid.

[79] Ibid.

[80] Ibid.

[81] Internal Security Act (Detained Persons) Rules 1960, arts. 71-72.

[82] Email from Edmund Bon to Human Rights Watch, August 8, 2005.

[83] Human Rights Watch interview with wife of detainee (name withheld), Kula Lumpur, July 2, 2005.

[84] Ibid.

[85] Human Rights Watch interview with wife of detainee (name withheld), Kuala Lumpur, July 2, 2005.

[86] Human Rights Watch interview with wife of detainee (name withheld), Kuala Lumpur, July 2, 2005.

[87] Handwritten statement of Abdul Murad bin Sudin, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[88] Human Rights Watch interview with wife of detainee (name withheld), Kula Lumpur, July 2, 2005.

[89] Human Rights Watch interview with wife of detainee (name withheld), Kuala Lumpur, July 2, 2005.

[90] Letter from Shukry Omar Talib to Professor Hamdan Adnan, Suhakam, undated, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[91] Email from Edmund Bon to Human Rights Watch, August 9, 2005.

| <<previous | index | next>> | September 2005 |