<<previous | index | next>>

IV. Reprisals: Gross and Systematic Violations of Human Rights

Arbitrary Arrest of Suspects

Groups of heavily armed Ba`th Party members, sometimes supported by members of the General Security Directorate, began arresting people in Basra the next morning, on March 18, and continued for several days. One detainee, Hussain, forty-five years old, told Human Rights Watch:

The next morning Ba`th Party members started to arrest people in our neighborhood [Tanuma, east of the Shatt al-Arab river from Basra]. They came in groups of approximately fifteen people, all dressed in olive Ba`th Party uniforms, in three pickups and one truck. My friend Muhammad Mazlum Hussain [age thirty-four] and I were arrested at nine in the morning on our way to the field where we worked. They blindfolded us, put us in a car and first drove us to the Ba`th Party building, located close to the Shatt al-Arab, then soon after to the Ba`th Party headquarters on al-Hakimi Avenue.16

The account provided by Jawad Kadhim `Ali about the arrest of his son, Mustafa, was typical of what several others described to Human Rights Watch:

Mustafa was arrested in 1999, March 1999. He was in the sixth grade [of high school, equivalent to the twelfth grade]. He was arrested because he was accused of taking part with a group against the government. He was accused of being for Ayatollah al-Sadr. He was arrested around forty days after the al-Sadr assassination. All the people were angry then but they did nothing because they were afraid.

On March 17 at around 11 p.m., a group opposing the government shot at government buildings, especially at Ba`th Party buildings. They killed some people in the government, some important people. All in all, they killed less than forty people. My son was accused of taking part in this group.

But that night [March 17] I was working as a taxi driver. I came home late, saw him asleep in his room. On March 19, I saw him asleep too when I returned home. That night, many armed people from the Security Directorate knocked on my door and said, “We need your sons.” They asked for Basim [my older son] and Mustafa. There were a lot of people there, some in uniform, others not. They were inside and outside.17

Many of those arrested during this period claimed that they had not participated in the uprising and were arrested as part of a round-up of all persons considered “suspicious” by the authorities. One of the duties of Ba`th Party members was to gather information and report about all suspicious activities in the neighborhoods where they lived. Nasir, sixty-three years old, whose three sons Ali, Muhammad, and Hassan were arrested, told Human Rights Watch:

They were not involved in the intifada, and were accused wrongfully. They [Ba`th Party members living in the same neighborhood] repeatedly came to my house [before the uprising] asking whether my sons `Ali and Hassan are going to go to Iran, and about Muhammad [who was studying religion at the seminary in al-Najaf, 140 miles northwest of Basra].18

Nasir described the arrest of two of his sons in the weeks after the uprising:

There was only one person from the Ba`th Party in our neighborhood, so there wasn’t much attacking by the protesters. I believe that person was attacked. Two of my sons were with me. They were in Basra, living with their families with us. [My other son] Muhammad was a talib [seminary student] in al-Najaf. He was at the final stage, after five years. He was almost done. He wasn’t in Basra when the fighting happened. When everything quieted down that night [March 17] I saw my two sons asleep at our house, so I fell asleep. I don’t think they were involved in the fighting, they were at home. We are not political people. We had no trouble.

On March 25 they searched my house. They were people in uniform, as well as Ba`th Party members. They were six people. The search occurred in the morning. They didn’t find anything then. After two days they came back to search. These were different people, five or six of them, probably Ba`th Party members. They also searched other houses in the neighborhood.

On April 7 at 2 a.m., a group of six came with a car. They entered the house. They jumped over the wall, broke the door. My sons were sleeping inside. There were five more people outside the house. That night they arrested `Ali and Hassan. We never saw them after that night.19

When suspects could not be immediately arrested, Iraqi authorities resorted to threats and trickery. In the case of Nasir’s family, Iraqi security officers enticed the mother of the family to turn in her son, who was at large, in exchange for the safety of her two incarcerated sons. As Nasir explained:

Three days later on April 10 they said if you bring the third one [Muhammad] for questioning we will set free the other two. We believed it was just for questioning. They had not done anything. So my wife went to al-Najaf in the morning to bring back Muhammad. He came voluntarily. He said he was going to help get his brothers free. So he went to the prison in Basra with his mother.20

Muhammad was never seen again by his family. By May 2003, with evidence mounting that Muhammad was killed by security forces along with his two brothers, Nasir described the toll taken on the family:

My wife has lost her mind. She has no peace anymore. She sits in the room and bites her fingers because she believes that she took her own son to be killed. Until now we could believe that they were alive. But now I have seen their names on the list. Two of their names. Maybe my third son is alive. No, we have to face the reality… They took all my sons. Now I have four girls left, and all their children. I have to take care of a family of eleven. Where are my sons to help me? 21

Some people managed to avoid arrest or bribed their way to freedom. Mahmud, forty-one years old, told Human Rights Watch that his brother Muhammad was in jail between April 4 and April 10, 1999, and was released after he paid $500 in bribes through a member of the Sa`dun family, a local tribe with a long history of cooperation with various Iraqi governments, including that of Saddam Hussein. Another brother, Ibrahim, and his family spent seven months in hiding.22

Mass Summary Execution and Burial at Unmarked Mass Graves

Basra residents told Human Rights Watch that hundreds of men arrested immediately after the al-Sadr intifada were never heard from again. Estimates of the total number killed vary. There was no official statement from the government about the crackdown. The Execution List obtained by Human Rights Watch names 120 people who were killed, although it is almost certain that more names appeared on other pages not in Human Rights Watch’s possession. The Basra Association of Political Prisoners, an organization established after the fall of Saddam Hussein by former political prisoners and dissidents, told Human Rights Watch that it had reliable information regarding 220 people executed in the first three months following the uprising. The Association based its claim in large part on documents it said it had retrieved from looted government offices, but Human Rights Watch was not able to examine or verify the contents of these documents. Local religious leaders, such as Sayyid Haidar Hassan of al-Jumhuriyya mosque, put the total number of executions at 350.23

Based on eyewitness testimony, the testimony of family members, and documentary evidence, it seems that the Ba`th Party and the General Security Directorate began executing people from the first days after they suppressed the 1999 uprising.

For instance, one eyewitness, `Abdullah, who was arrested immediately after the uprising, told Human Rights Watch: “A squad of Ba`th Party members drove us to the party headquarters on al-Hakimi Avenue. There were over fifty people there. Some of them were shot on the spot right there. I heard gunshots and people screaming.”24

However, most of those executed seem to have been killed en masse and buried in unmarked graves around Basra. For instance, the Execution List identifies four separate groups of men executed together between March 25 and May 8, 1999.

Human Rights Watch separately interviewed two witnesses who claimed to have seen mass executions and burials in and around Basra in the spring of 1999. Their accounts independently corroborated a reported pattern of executing detainees in groups and burying them in mass graves, consistent with the crackdown on the al-Sadr intifada.

Ahmad, a seventeen-year-old shepherd, told Human Rights Watch that in the late spring or early summer of 1999, he saw on several occasions people in military uniforms bringing prisoners by trucks to al-Toba, an area one mile from Shaibah West Airfield (currently a British military base). Ahmad said he was hiding on a nearby hill, three to four hundred meters away from the trucks. From that vantage point, he said he could see that these prisoners were literally thrown out, in groups of ten to fifteen, from the trucks into holes previously dug in the ground the day before. This is what he saw next: The people in military attire shot all of the prisoners and used bulldozers to cover up the holes. Ahmad claimed that he could tell that some of them were buried alive.25 When Human Rights Watch researchers visited the site in mid-May 2003, bones and what seemed like a human skull were visible on the surface of the site, which was also strewn with items of clothing. Parts of the site was covered with abandoned ammunition, including artillery shells, which deterred unauthorized excavation at the site.

Al-Toba, outside of Basra. This is a

site where witnesses claim they saw mass executions and burials take place in the spring of 1999.

Human

Rights Watch investigators visited the site in May 2003 and found

evidence of what appeared to be human bones and clothing.

(c) 2003 Human Rights Watch

Al-Toba, outside of Basra. This is a

site where witnesses claim they saw mass executions and burials take place in the spring of 1999.

Human

Rights Watch investigators visited the site in May 2003 and found

evidence of what appeared to be human bones and clothing.

(c) 2003 Human Rights Watch

Sattar, a twenty-seven-year old cattle herder, told Human Rights Watch how he witnessed the execution of a group of prisoners at another site near the old al-Nasiriyya road southwest of Basra:

One day in the spring of 1999, I saw a bulldozer digging three big trenches in a remote deserted area southwest of Basra where I used to take my herd. I didn’t pay that much attention even if it looked weird. The next morning at about 9 a.m., while at the same place again with my herd, four buses and six Ba`th Party-like cars arrived on the site. I was hidden 350 to four hundred meters from the vehicles. I saw men in military attire exiting from the cars and then blindfolded prisoners, hands tied in back, stepping one by one out of the buses. Each bus had the capacity to transport around forty to fifty passengers.

I can’t say if the buses were full because curtains shaded the windows. According to my estimate, but without any certainty, between eighty and one hundred persons might have been in the buses. The prisoners were led in a line to the trenches where they were placed one by one. At that point, I was unable to see them anymore. I can’t say if the prisoners were made to kneel or sit in the trenches. Seconds later, the men in uniform began shooting randomly at the prisoners with AK-47s and BKC machine guns. The shooting lasted several minutes. Then, a truck covered up the trenches with sand and dirt. When it was all over, the men in uniform left the place quickly. The entire operation lasted 45 minutes.26

When Human Rights Watch researchers visited the site, they found it also strewn with unused ammunition and unexploded ordnance, much of it showing signs of rust.

Sattar told Human Rights Watch that a few weeks after he witnessed the executions at the site, he saw military trucks return to the area and dump ammunition on top of the newly covered graves. Military cars then routinely toured the area, apparently to deter or detect any attempts at exhumations.

The strongest evidence in support of the Execution List’s authenticity, and the accuracy of accounts regarding mass execution and burial of the victims of the 1999 massacre, was literally unearthed with the exhumation of remains from al-Birgisia, an area thirty miles south of Basra.27 On May 11, 2003, `Ali Hassan, a twenty-year-old shepherd, told Marc Santora of The New York Times that he saw men brought by Ba`th Party trucks to an open clearing at al-Birgisia, where a backhoe dug a long trench, and the men, blindfolded, were lined up in front of the ditch and shot.28

Thirty-four bodies exhumed from this site on May 7, 2003, were taken initially to a soccer stadium in Basra, and then to al-Jumhuriyya mosque, in a poor Basra neighborhood. When Human Rights Watch researchers first visited the mosque on May 13, 2003, some of the remains were clearly incomplete.

Human remains brought to the mosque were

usually incomplete.

(c) 2003 Human

Rights Watch

Twenty-nine of 34 sets of remains were

identified by family members.

All 29

names of those identified appear on the execution list. This coffin is

labeled "Unidentified."

(c) 2003 Human Rights Watch

Relatives claimed to have identified twenty-nine bodies. A handful of families were fortunate enough to find a driver’s license or a school identity card that could provide a name to a bundle of bones and clothes. Most families cited much weaker evidence for their identifications, relying on clothing, jewelry, even a favorite brand of cigarettes.

Grief-stricken family members mourn the

death of their loved one after

digging up remains at a massacre site.

Some families relied on simple

items such as watches, shoes and even cigarette packets to identify the

remains they had recovered.

(c) 2003 Human Rights Watch

Forensic scientists refer to this type of identification as “presumptive identification.” Because the type of personal items used for presumptive identification can be exchanged or misplaced, this process of identification has less credence than “positive identification” methods using unique biological characteristics such as DNA, dental records, or fingerprints. The risk of false identification can be reduced by some rudimentary precautions—for instance, asking family members to note what they remember their missing loved ones were wearing before they viewed the remains. In the chaotic conditions prevailing at this exhumation in Basra, no such measures were taken.

Despite the circumstances surrounding this exhumation, all the names of the twenty-nine bodies presumptively identified from the al-Birgisia gravesite appeared on the Execution List. While this appears to corroborate the authenticity of the Execution List, the methodology used by families to identify remains also raised the possibility that some families misidentified remains because the names on the list had convinced them that they would find their missing relatives there.

Ibrahim believed he had identified the bodies of his two brothers, Zia and Majid, on May 10:

Four days ago we identified their bodies when people brought them to the soccer stadium. They are here now, at the mosque. We identified them by their clothes. Zia was wearing a checked T-shirt, Majid, a blue blouse. Other people had personal items on them that we could easily identify like rings, gold teeth, and the like. They were all laid in the mass grave, on top of each other. It looked like they had been blindfolded and their hands tied up before they were killed: we found ropes and pieces of cloth on the eyes on many of the bodies. All of them, including Zia and Majid, had gunshot wounds in their heads.

People just began digging up the bodies and they told other people what they had found. One of the bodies had an identity card in the clothes. The name was found in one of the execution lists.29

A separate interview with another brother of Zia and Majid, `Issa, forty-one years old, confirmed this account.30 Zia and Majid’s names appear in the Execution List, which refers to March 25, 1999, as the date of their execution.

Nasir, whose three sons had been arrested in 1999, believed he found the bodies of two of them: Ali, twenty-six years old, and Hassan, twenty-four years old. Their names are included on the Execution List, with the date of execution noted as May 8, 1999.31 The third son, Muhammad, twenty-five years old, remains missing. His name does not appear on the pages of the Execution List in Human Rights Watch’s possession.

On May 14, 2003, all the remains, including five unidentified bodies, were taken to al-Najaf for burial. The bodies, reburied without proper forensic examination, thus took with them to the grave any information they could have provided about their identities and the manner of their death.

Arbitrary Detention and Abuse of Family Members of Suspects

In addition to the execution of scores of young men, many family members of those suspected of involvement in the al-Sadr intifada were imprisoned for months without any judicial procedure. The arrest of one family member was, as a rule, followed by arrests of some or all other members of the family. Ibrahim, whose two brothers Majid, twenty-one years old, and Zia, twenty-years old, were arrested and apparently executed in 1999, told Human Rights Watch: “The rest of the family, including my brother Ahmad [age forty-seven], Ahmad’s wife, their two children, aged two and four years old, [and] my sister [age twenty-seven], were arrested on March 23.”32

All of the detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they were transported first to the Ba`th Party headquarters in Basra and after that to a building or prison of the General Security Directorate. Ba`th Party members carried out preliminary screening of the people detained.

Detainees told Human Rights Watch that they were kept in cramped conditions and, in at least one case, subjected to severe torture. One detainee, Hussain, recounted:

They took me to the General Security Directorate compound and put me in a very tiny cell with twenty or twenty-five people. We could barely stand. We were kept there until midnight then they started, what they called, investigation. They picked us out in groups of two or three for interrogation. They asked questions about the uprising and about our possible connections with Iran. Then they tortured us trying to get confessions. They poured hot water on us, used electric shocks on the body and genitals, or poked us with red-hot rods. We spent six months in that cell, and the following four months in a bigger one. During the first month they tortured us almost every day, then less frequently but on a regular basis, once or twice a week.33

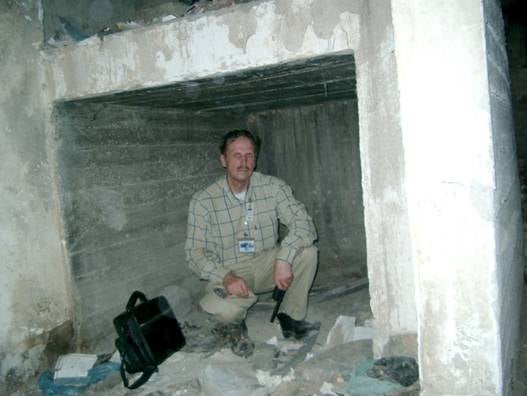

Some of those who had not confessed in Basra were transferred to the General Security Directorate in Baghdad. As Hussain explained: “I spent ten more months there. Instead of physical torture, they used psychological torture. For instance, I spent a week in a dark, small low ceiling room, lower than one meter. We could not leave the room at all, even to go to the restroom.”34 Human Rights Watch observed several cells matching Hussain’s description in the General Security Directorate main prison in Basra as well as in Abu Ghraib prison in Baghdad.

Human Rights Watch investigator inside a former isolation cell at the

General Security Directorate in Basra.

(c) 2003 Human Rights Watch

Many family members who initially escaped or avoided detention were later rounded up as well. Jawad Kadhim `Ali described his arrest:

Twenty-five days later [after Mustafa’s arrest on March 19, 1999], they came to my house, took my family, my wife, and my twin sons [born in 1982]. My two daughters escaped to our neighbors. I was at work at the time, people told me that there was trouble. I came home at 2 p.m., I saw that everything is empty in the house, the doors are pulled out, the wires are pulled out, the furniture is all moved out. The neighbors said, “Your family was arrested.” They said they didn’t know who arrested them, maybe the Ba`th Party.35

So I told my relatives I will go after my family, but they prevented me. They said, “Maybe they will hurt you.” I said this is my family, if I can’t help them I must share their fate. I went to the Ba`th Party headquarters, but they said my family was in the Security Directorate. I went there, and they said we have to arrest you. I said, “I’m ready,” but I begged them to put me with my young sons, the twins.36

Nasir avoided arrest for nearly two months before he, too, was imprisoned:

I was arrested on June 17 at the al-Ashshar market . Two security police in uniform arrested me. They asked me for my ID. I refused, but they said we’ve come to arrest you because your sons are in prison. So they knew very well who I was.

They kept me in the Security Directorate in Basra for eight days, in the jinaya [felony] wing. Later I was transferred to the al-islah [correctional] prison. My family was also there. They had been in al-tasfirat [transfer prison] for one month, then transferred to al-islah. We were all there in that prison for three months. The women were in a separate room. We learned that they were safe, but my sons were not in that prison.37

The conditions in the prisons where members of the families were kept were difficult. Ibrahim told the story of his brother Ahmad’s family:

The family spent seven months [in detention], first in al-tasfirat prison. In May, they were transferred to a correctional facility opposite al-Jumhuri hospital. The women in al-tasfirat prison were kept in one big cell together with their children. Approximately seventy female prisoners were put in a cell, ten by twelve meters. Several women gave birth in the prison. They were taken to hospital for two hours, and then returned to the cell with the newborn babies. Only one toilet was inside the cell, and the women lined up to use it.38

Jawad Kadhim `Ali also provided a description of conditions in prison:

I was taken to the Ma`qal, the al-tasfirat prison, in front of the railway station in the center of Basra. I stayed there for one month and three days. Then they took all of us to the main prison in front of al-Jumhuri hospital. At this time they set free my eldest son Basim. But because there was no one at home, they sent him to his family in jail. Basim was held by the Amn [General Security Directorate] of Shatt al-`Arab.

In the Ma`qal prison, we were seventy to eighty people in a cell four meters by six meters. There was one toilet also open in the cell. We could not receive any letters, no radio, no visitors, no food from outside. They gave us each one, two or three loaves the size of a hand, and soup—I call it soup, but it was carrot water.

There were another three rooms in the prison, about the same size with the same number of people in them. All the others in the cells were related to the al-Sadr operations. There were nearly one thousand people in jail. The women and children were also in a cell at Ma`qal prison.39

Children and even pregnant women were not spared the harsh prison conditions. Nasir’s granddaughter—the child of his youngest son—was born while in prison. “She was born in jail because her mother was also in prison with the rest of us. They gave her one day to go to the hospital to give birth, and then they returned her to jail with her new daughter.”40

Collective Punishment: House Demolitions and Displacement

The Iraqi government routinely demolished the houses of those they suspected of involvement in the uprising. Every detainee interviewed by Human Rights Watch described this form of collective punishment. In Basra, Human Rights Watch visited four sites of houses destroyed in 1999 as punishment for the occupants’ alleged involvement in the uprising—one in al-Shamshumiyya neighborhood, two in Ma`qal, and one in al-Tanuma. All these dwellings were razed almost immediately after the arrest of the families living in them. Sayyid Haidar al-Hassan, a leading cleric at the al-Jumhuriyya mosque and a community leader, told Human Rights Watch that after the first week following the uprising alone, fifty-one families were arrested and their homes demolished.41

As was the case with other suspects, the government destroyed Nasir’s family’s house as collective punishment for their suspected involvement in the uprising against the government. Nasir described what happened:

On April 12 they came to our house around noon. They arrested the whole family. I escaped that day. The next day, they came back and razed the house. They tore it to the ground. I just stayed away. I went to the al-Ashshar district [and] stayed with my friends and people who knew me. I moved around all the time. I tried to get information about my family from neighbors and family. Through them I heard that my family was in al-tasfirat prison.42

Neighbors and the Basra Association of Political Prisoners provided Human Rights Watch with information about the fate of some of those families whose houses were destroyed, as grouped by neighborhood:

Al-Shamshumiyya:

Ma`qal:

Al-Tanuma:

Another form of collective punishment was barring detainees’ family members from most types of official employment. Jawad Kadhim `Ali’s condition was typical:

While in prison, I had lost my job as a teacher. I was rehired as a clerk at the education ministry, but I was prevented from teaching. My salary was 3,000 dinars [a month]—it was nothing. It couldn’t pay for anything. So I applied for jobs as a carpenter. I built furniture with my hands. It is a proud job, and I taught Basim [my son] to be a carpenter also. I taught him that we were proud. We could work with our hands. We didn’t have to beg. I also worked as a taxi driver. But I couldn’t hold another job. It was prohibited.43

Nasir, who had worked as a physical education teacher, was also left unemployed.

I was a physical education teacher before. I was a famous football player then. Don’t look at me now. Every one in Basra knew me. I even played for the national team, against England, against Iran, against Russia, in the 1970s. When we were released from prison I couldn’t work. They didn’t let me work. We were very poor. So some people who knew people in the government told them, “What can this man do? Let him have a job.” So I was given the job of giving out coupons for the Oil for Food program. I just had a small stall. It was the size of one person. I sold the coupons and other things. And that’s how I made money to pay for my family and my sons’ families. Now I hope to work again, maybe teach, but I am old.44

[16] Human Rights Watch interview with Hussain, May 9, 2003, Basra, Tanuma neighborhood.

[17] Human Rights Watch interview, May 8, 2003, Basra, Tanuma neighborhood.

[18] Human Rights Watch interview with Nasir, May 10, 2003, Basra, Tanuma neighborhood.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Human Rights Watch interview with Mahmud, May 10, 2003, Basra, Tanuma neighborhood.

[23] Human Rights Watch interview with Sayyid Haidar Hassan, May 13, 2003, Basra, al-Jumhuriyya mosque.

[24] Human Rights Watch interview with Abdulla, May 9, 2003, Basra, Tanuma neighborhood.

[25] Human Rights Watch interview with Ahmad, May 14, 2003, Basra, al-Toba, al-Anfal Company.

[26] Human Rights Watch interview with Sattar, April 25, 2003, Basra, al-Zubair.

[27] Contemporary statements from the Iraqi Communist Party identified al-Birgisia as the location of a mass execution and burials. See, “Iraqi Opposition Says Mass Grave Found in Desert,” Associated Press, September, 27, 1999, citing a press release by the Iraqi Communist Party.

[28] Marc Santora, “Mass Grave is Unearthed Near Basra,” The New York Times, May 11, 2003.

[29] Human Rights Watch interview with Ibrahim, May 14, 2003, Basra, al-Jumhuriyya mosque.

[30] Human Rights Watch interview with `Issa, May 10, 2003, Basra, Tanuma neighborhood. Zia and Majid are pseudonyms; their real names are among those on the Execution List reproduced in the Appendix to this report.

[31] Ali and Hassan are pseudonyms; their real names are among those on the Execution List reproduced in the Appendix to this report.

[32] Human Rights Watch interview, May 10, 2003, Basra, Tanuma neighborhood.

[33] Human Rights Watch interview with Hussain May 9, 2003, Basra, Tanuma neighborhood.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Human Rights Watch interview, May 8, 2003, Basra, Tanuma neighborhood.

[36] Human Rights Watch interview, May 8, 2003, Basra, Tanuma neighborhood.

[37] Human Rights Watch interview with Nasir, May 7, 2003.

[38] Human Rights Watch interview with Ibrahim, May 10, 2003, Basra, Tanuma neighborhood.

[39] Human Rights Watch interview, May 8, 2003, Basra, Tanuma neighborhood.

[40] Human Rights Watch interview with Nasir, May 7, 2003, Basra.

[41] Human Rights Watch interview with Haidar al-Hassan, May 13, 2003, Basra, al-Jumhuriyya mosque.

[42] Human Rights Watch interview with Nasir, May 10, 2003, Basra, Tanuma neighborhood.

[43] Human Rights Watch interview, May 8, 2003, Basra, Tanuma neighborhood.

[44] Human Rights Watch interview, Nasir, May 10, 2003, Basra, Tanuma neighborhood.

| <<previous | index | next>> | February 2005 |