<<previous | index | next>>

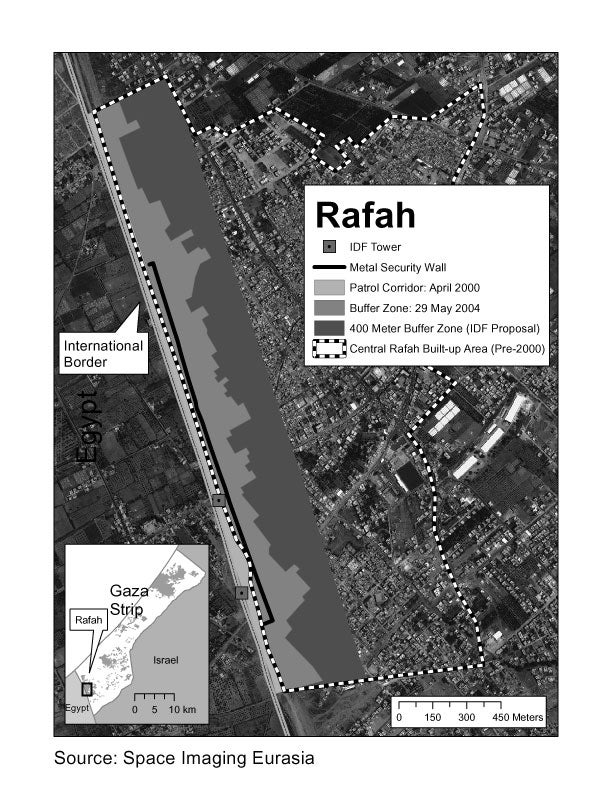

Map 4 : Existing and Proposed Buffer Zones

The indiscriminate destruction of entire neighborhoods of Rafah would result in the forced displacement of tens of thousands of people. The IDF’s “grave suspicions” of more advanced weapons possibly entering Rafah through Egypt at an indeterminate point in time in undetermined circumstances cannot justify actions that, under international law, must be “absolutely necessary” for combat activities. Moreover, as demonstrated in this report (see Chapter 4), Israeli forces should be able to effectively prevent smuggling through tunnels using less destructive means.

Plans for expanding the buffer zone accelerate in tandem with preparations for “disengagement.” The plan explicitly envisions the possibility of further demolitions in Rafah on the basis of vague “security considerations” without making any reference to actual combat. As Article 6 of the plan states:

The State of Israel will continue to maintain a military presence along the border between the Gaza Strip and Egypt (Philadelphi Route). This presence is an essential security requirement. At certain locations, security considerations may require some widening of the area in which the military activity is conducted.171

Impact of Destruction

Whether along the border or deeper into the camp, house and property destruction in Rafah has had a severe impact on the community. Most concretely, homelessness places a heavy burden on poor families, who are forced to rent or buy new homes, or in many cases live with relatives. Trauma, tension, and anxiety have risen, as has violence at home and in schools. Malnutrition and physical illnesses are serious concerns for the international agencies that already keep much of the Gaza Strip afloat through programs and aid.

In the aftermath of the May incursions, documented in detail below, UNRWA temporarily housed approximately two thousand five hundred people in three of its schools, with up to fifty people in one room. That number dwindled as families found alternative housing with relatives, rented new homes or occupied empty spaces in town, but UNRWA noticed a “relatively slow movement” out of their schools, indicating a saturation of the housing market.172

A Rafah family's sleeping room at a UN school in July, two months after the IDF destroyed 298 homes.

Rafah is one of the most densely populated towns in the world, and housing is in short supply.

(c) 2004 Fred Abrahams/Human Rights Watch

The demolitions have dramatically reduced available housing in what was already one of the most densely populated areas on earth. Funds are available to rebuild approximately one thousand housing units – barely half of what has been destroyed. Construction, however, has been delayed in part because of the lack of available land in the Gaza Strip. In other cases, rebuilt homes remain vacant due to the danger posed by nearby IDF bases.

Fathiya Abdul Rahman Abu Tueor, for example, was one of six families still living in the al-Khansaa elementary school when Human Rights Watch visited on July 15. She explained how she and her family had fled their house in Block O when a tank knocked down a wall on May 12. “It was totally destroyed,” she said. “We lost everything, all our furniture, our books and even our IDs.” For one month afterwards, thirty people slept in one room at the school, but by July they were down to ten.173

In the same school, Sabreen Faramawi from Block O, who fled on May 12 when her house was hit by IDF shelling, complained how difficult it was to find a new home. “We have no plans for the future. There are no empty flats in Rafah. It will cost U.S.$ 140-150 per month she said. “And it will not be like our old house, it will be small and without necessities. We are calling out for help but nobody pays attention. We have no water and we have to buy it from the store.”174

Qifaya Abu Shar and her family was living in the UN's Boys Prep B school two months after IDF forces destroyed their Brazil home on May 19. Five members of the family hid in a back room as a bulldozer destroyed part of their home. "I was amazed the sun rose and we were still alive," she said.

(c) 2004 Fred Abrahams/Human Rights Watch

In Boys Prep B school, Qifaya Abu Shar explained how she and her family were awakened abruptly on the night of May 19 when a bulldozer knocked down their neighbor’s house in Brazil. Five members of the family hid in a back room as the bulldozer destroyed part of their home. “I was amazed the sun rose and we were still alive,” she said. They went to the UNRWA school when the army withdrew. At first, six families lived in one room, she said, about fifty people. By July ten people were sleeping in one room.175

In addition to those made homeless, some families remained in their homes near the border despite the constant shooting and risk of military incursion. Mahmoud Fathi said that he and his family stayed in their house in Block J, in view of the Philadelphi Route and one of the few houses in the area still intact, because they had no money to live someplace else. “No one can live upstairs because a bullet can come at any moment,” he told Human Rights Watch. “But the ground floor is protected by rubble from houses destroyed in Rainbow. This was one of the most affected areas. Like always, they used the tunnels as an excuse to destroy the neighborhood.”176

Human Rights Watch also met residents who slept with relatives in cramped homes and spent days in and around their damaged or destroyed homes, where they enjoyed more space and proximity to friends. Naim Abu Jarida, for example, told Human Rights Watch that a bulldozer had destroyed his house just west of the Rafah zoo on May 19. The family had fled temporarily the day before and all their possessions were lost. UNRWA gave the family money to rent a new home but they spent their days at the remains of their old house, a pile of concrete, lounging under a makeshift shelter of aluminum siding.177

One man, Jamal Radwan, thirty-seven years-old, had lived in Block O for thirty-three years. His house was partially destroyed on March 17, 2004, but it remained livable for Jamal and seven family members, he told Human Rights Watch. That ended in May 2004, when IDF bulldozers destroyed the rest of his house, leaving only a fractured piece of white.

Jamal Radwan in front of where his house in Block O stood until the IDF destroyed it on May 14. "I still come every day to Rafah because my whole life is in Rafah," he said. Block O used to extend to the edge of the Israeli patrol corridor but successive demolitions since 2000 have wiped away large portions of the neighborhood.

(c) 2004 Fred Abrahams/Human Rights Watch

When Human Rights Watch met Radwan, he was sitting by himself on a stoop in Block O near his demolished home. He lived with his brother in a house several kilometers north of Rafah outside of Khan Yunis, he said, but “I still come every day to Rafah because my whole life is in Rafah. I can’t live in Khan Yunis. I come here to see the people.”

Because he and his family were living with his brother, they were not eligible for a new house from UNRWA, Radwan said, showing a letter from UNRWA to that effect. He used to run a fruit and vegetable shop near Salah al-Din gate, but it was demolished in November 2003, and now work is hard to find. “I’m living with my brother but sooner or later I need to rent an apartment,” he said. “He can’t support me forever.”178

[171] “Revised Disengagement Plan – Main Principles,” adopted June 6, 2004, Art. 6.

[172] UNRWA and OCHA, “Rafah Humanitarian Needs Assessment.”

[173] Human Rights Watch interview with Fathiya Abdul Rahman Abu Tueor, aged forty-five, Rafah, July 15, 2004.

[174] Human Rights Watch interview with Sabreen Faramawi, aged twenty-three, Rafah, July 15, 2004.

[175] Human Rights Watch interview with Qifaya Abu Shar, aged thirty-seven, Rafah, July 15, 2004.

[176] Human Rights Watch interview with Mahmoud Fathi, aged twenty-one, Rafah, July 15, 2004.

[177] Human Rights Watch interview with Naim Abu Jarida, aged thirty, Rafah, July 14, 2004.

[178] Human Rights Watch interview with Jamal Radwan, aged thirty-seven, Rafah, July 15, 2004.

| <<previous | index | next>> | October 2004 |