<<previous | index | next>>

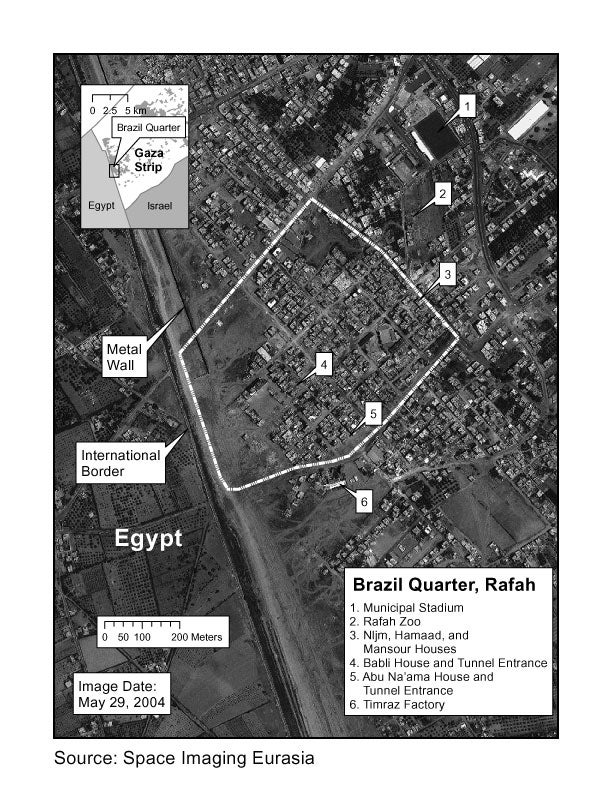

Map 7: Brazil Features

Brazil and Salam (evening May 19-morning May 24)

Despite the international outcry after the killing of the demonstrators outside of Tel al-Sultan, the IDF accelerated its operations by launching an offensive deep into Brazil and the neighboring Salam area for the first time in the uprising. According to UNRWA, the IDF demolished 154 houses in Brazil and Salam. Four Palestinian civilians were reportedly killed, including a three-year-old girl shot near her home and a three-year-old boy who died of shock from a house demolition. Four armed fighters were also killed by helicopter-launched missiles. Most of the dead were killed in the initial hours of the incursion, except a three-year-old girl reportedly shot by IDF snipers near her home in Brazil on May 22. The IDF said that the reason for its incursion was to search for tunnels and eliminate or arrest militants. Although Brazil and Salam are located near the border, much of the initial destruction occurred in areas deep inside Brazil, closer to the center of the camp, up to one kilometer from the border.

Two patterns of house demolition are evident in Brazil. In the interior of the camp, the IDF bulldozed paths through blocks of one-story houses. An IDF officer confirmed to Human Rights Watch that there was a general directive for the Brazil incursion to stay off of main roads whenever possible in order to avoid potential bombs, irrespective of any specific threats. Approaching the border, destruction seems to have been progressively more indiscriminate, leveling wider swathes of housing.

The assault on Brazil began before midnight on May 19. Tanks and Caterpillar D9s quickly moved into Brazil from the north and east while Apache helicopter gunships fired missiles into the camp.

The Rafah zoo marked the deepest point of penetration into Rafah, where Israeli forces set up a perimeter to isolate Brazil nearly eight hundred meters from the border. En route to the zoo, IDF D9s plowed through several fields, homes, and a factory. Sami Qishta’s one-story house was one of those destroyed near the zoo:

I was sitting in the house and suddenly I saw the bulldozer next to me in the house. I heard them but I didn’t think they were coming to destroy my house. I was inside for fifteen minutes while they hit it from different sides. Then they stopped and I left. I couldn’t leave before then. When I tried to leave the house they said to me in Arabic, “Don’t leave! We’ll destroy it on your head!”248

Mohammed Juma’, one of the owners of the zoo, saw an armored bulldozer breach the outer wall of the compound around midnight, crushing an ostrich in its cage:

I ran in front of the bulldozer and started shouting in Hebrew that this was a zoo and not to destroy it. They fired a sound bomb at me and I went back to the balcony of my house. … The bulldozer circled in the courtyard for fifteen minutes and then left. As it was leaving, a tank came, entered, circled, left, without destroying anything. Half an hour later, two [Israeli] bulldozers, marked “4” and “7,” and one tank entered. And then the movie started. Over the next six hours, they demolished the entire zoo. They didn’t leave anything behind. No trees, no cages, no animals.249

The demolition of the zoo and adjacent olive grove owned by the Qishta family was a time-consuming and deliberate act at the farthest point of advance into the camp, not one taken in the heat of battle or while en route to another objective. After the zoo and olive grove were leveled and the debris was moved away, three Israeli tanks parked in the compound for the next day; two more guarded the perimeter. A group of IDF soldiers also seized control of Mr. Juma’s four-story house, located in the same compound, and confined his family to one room, except his brother, who was kept on the roof.

Residents in the area said there had been no shooting at Israeli troops. The IDF bulldozer driver who razed the zoo told an Israeli journalist that he had been ordered to destroy the zoo to “keep them from shooting at our soldiers from there.” When asked if this meant that there was no shooting from the zoo, he replied: “They said it would endanger the lives of soldiers, so I destroyed it. I do not ask questions. That is not my job. They tell me to demolish something and I do it.”250

After denying that the zoo had been destroyed, the IDF explained that it had destroyed the zoo while en route to another objective and because an alternate route had been booby-trapped.251 The zoo, however, seems to have been the edge of the IDF cordon rather than on the way to any other destination.

The zoo was one of the few recreational areas in an overcrowded camp whose residents have been denied access to the sea by Israeli settlements for the past four years. Thousands of animals, including jaguars, crocodiles, wolves, snakes, and birds escaped from the zoo or were killed during its demolition. According to documents that Mr. Juma’ showed to Human Rights Watch, the total value of damages to property and animals totaled nearly U.S.$ 800,000. The IDF also destroyed two UNICEF-funded playgrounds during the May 18-24 incursions, one in Tel al-Sultan and one in Brazil,252 although Human Rights Watch has not investigated the circumstances of these incidents.

The IDF’s claim that the zoo was bulldozed en route to another location is not consistent with the facts. Rather, given that it was the furthest point of advance in the camp, the deliberate and time-consuming nature of the destruction, the seizure of the four-story Juma’ house, and the stationing of several tanks there for over a day, it seems more likely that the IDF used the area to enforce a cordon separating Brazil from central Rafah. Most important, there is no indication that this destruction was done in response to gunfire or in the heat of battle.

The destruction of the zoo was not justified by absolute military necessity. Even if it had been justified to destroy the zoo and olive grove and convert them into a strongpoint, a less destructive alternative was easily at hand. For the purposes of sealing off Brazil from central Rafah, the municipal stadium across the street from the zoo would have provided similar tactical value to the IDF while entailing less destruction. While the four-story Juma’ house may have made it a more appealing observation point than the two-story building in the stadium compound, the stadium offers other tactical advantages. It was already an open space, equipped with lights, and surrounded by a wall. Converting the stadium into military use may have necessitated tearing down the chainlink fence around the grass and damaging the field. This would have been easier both to destroy and to repair than the zoo, with its multiple cages, fountains, and animals, as well as the hundreds of decades-old olive trees in the adjacent grove.

After sunrise on May 20, the IDF continued destroying homes in the interior of Brazil, nearly seven hundred meters from the border. From the roof of his four-story home, Mahmoud Nijm saw an armored bulldozer and two tanks make their way southward from the area of the zoo, several blocks away. The D9 cut a path through several one-story shops, passed in front of Mr. Nijm’s building, and then turned southward to plow through a block of one-story houses bordered by taller buildings:

Behind the bulldozer were two tanks. They stopped in the street to the south of my building, and were facing two different directions. The bulldozer then destroyed the home of Jamal Abu Hamaad, across the street from me to the south. … I saw the roof falling in, the family was shouting from inside and the bulldozer stopped. The people came out through the hole in the front and left. I didn’t see where they went, maybe to the neighbors. The bulldozer then destroyed the house.253

Human Rights Watch found Jamal Abu Hamaad’s wife, Fariyaal, still living in a local elementary school two months after losing her home. She confirmed Mr. Nijm’s account of the destruction of her home:

I was sitting in my home in the morning. I heard a bulldozer outside. I thought it was a Palestinian bulldozer at the time. I didn’t realize it was a military operation. They started firing bullets at the door of the house. One minute, [the bulldozer] came into my son’s part of the house and destroyed it. When the bulldozer pushed into my room, I saw the driver … who motioned with a hand to get out. All of us gathered in the last room of the house. The bulldozer was plowing through the rest of the house. We had white flags and didn’t take anything from the house. We came out through the hole in the wall punched by the bulldozer.254

Fariyaal Abu Hamaad's home in Brazil was destroyed by an IDF bulldozer on May 20, 2004. "All of us gathered in the last room of the house," she said. "The bulldozer was plowing through the rest of the house."

(c) 2004 Fred Abrahams/Human Rights Watch

According to Mr. Nijm, the armored bulldozer proceeded to completely destroy a row of three small houses before pushing southward:

The bulldozer then turned to the house next to [the Abu Hamaad house], which belongs to ‘Emad Mansour. A man came out with his hands up, and was talking to the soldiers. The family brought out one box and then left. The house was destroyed. The third house in the row belonged to Mohammed Abu Tayema and was empty at the time. The bulldozer destroyed it. It pushed all the debris onto a side street and also into the house of Mansour Mansour, which was just to the south of the three homes.255

Interviewed separately, Mansour Manour’s son Mohammed confirmed this account, telling Human Rights Watch:

They demolished the kitchen wall and we all ran outside. We went to the Hassan family house, which was just west of our home. Maybe there were fifty people in there all together. The bulldozer came after us. We all ran to the Qishta house. When the bulldozer came, the women went out with a white flag, and then we all went to the nearby school.256

The bulldozer soon broke through to the next street and crossed over to the house where Mr. Nijm’s brother, mother, and other relatives were: “The bulldozer moved the debris through the block towards the house where my brother and mother were. … When they destroyed the house I thought that they had died.”257

Mr. Nijm’s brother Husayn told Human Rights Watch:

During the night there was noise and destruction. I woke up and my wife said that the shooting [from the IDF overnight] had stopped. … I soon saw a bulldozer from my window across the street destroying homes. There was no time to get anything. The bulldozer was coming towards the house. My wife and brother’s wife took the children, I picked up my mother – she weighs eighty-five kilos!

We escaped through a hole in the back of the house. I fell while carrying my mother but my neighbor helped me with her. We went through that house, crossed the street, and put everyone in another neighbor’s house. I circled back to the end of my street to see my house being destroyed. Everyone was crying. The whole thing took about four minutes.258

The demolition continued throughout much of May 20 and appears to have been more indiscriminate in areas closer to the border. Houses alongside wide streets were partially demolished, while other blocks of one-story homes were bulldozed. Video footage and photographs taken in the immediate aftermath of the incursion show roads torn down the center, a pattern consistent with the use of the back ripper of D9 bulldozers. The destruction of roads caused serious damage to both water and sewage systems, and often created a mixing of the two.

Some homes could not be destroyed for any identifiable reason, justified or otherwise. Next to Subhi Abu Ghali’s two-story house is the space where his father’s house used to be. It was a one-story asbestos-roofed home, approximately 125 square meters in area. None of the surrounding houses were destroyed, there were no tunnels in the vicinity, and there were nothing to indicate that the house had been used to fire upon the IDF. On the morning of May 20, Abu Ghali, who works as an UNRWA nurse, put on his health worker’s vest and brought his father into his house before stepping outside to plead with the soldiers. He told Human Rights Watch:

We started yelling towards the soldiers. I had my UNRWA health department vest on. We were in the street for ten to fifteen minutes: my wife, my mother, my kids, and me. Only my father was still inside my house. We watched the bulldozer destroy my father’s house. I thought they were coming to destroy my house too. I carried my father and we walked in the street. I saw other homes being destroyed. It was difficult to carry my father. They were shooting into the ground near us.

My children didn’t want to leave me. I put the kids and my father in a neighbor’s house. My wife and I took my son from the house to the neighbors’ house. We made multiple trips. They were shooting at the ground and at walls the whole time. … They were seeking revenge. My father is a ninety year old man; does he have a tunnel or a weapon?259

The IDF left the center of Brazil on May 21, keeping tanks in the streets to close off areas closer to the border. Snipers were still positioned in several buildings in the neighborhood, firing at residents throughout the next day. Rawan Abu Zaid, aged three, was reportedly shot and killed by IDF snipers on May 22 while near her home, at the same time as a visit to Brazil by UNRWA Commissioner-General Peter Hansen.260

On May 23, the IDF announced the discovery of an eight-meter deep tunnel in Brazil the previous day; two days later, IDF Gaza Division Commander Brigadier General Shmuel Zakai clarified that the tunnel was an incomplete shaft eight meters deep.261 Rafah residents believe that the shaft was the one in the Babli house, which the PNA had already sealed.

On the morning of May 23, the IDF destroyed a home belonging to the Namla family near the Babli house. The Namlas lived in two adjacent houses: a one-floor house used by the grandparents and a four-story building divided between the families of their sons. After the IDF bulldozed half of the grandparents’ house and pushed debris into the other half, four bulldozers converged on the larger house. Protracted negotiations, going on for one to two hours, ensued. The IDF soldiers took two of the women of the family away for a brief interrogation, during which they asked about tunnels in the area, while the family frantically called the ICRC and the Mezan Center for Human Rights, eventually reaching an IDF legal adviser. Mohammed Namla, one of the grandsons, told Human Rights Watch what happened next:

My father spoke with the legal advisor [by phone], who asked if we were really inside the house. “We’re inside the house right now,” we told him. He said that the commander told him the house was empty. The legal advisor asked for our address and said he would call back. After fifteen minutes he called and said, “The demolition will be stopped. We won’t demolish your two houses.” But the first one was already destroyed.262

The Namla family also managed to contact a local radio station while the D9s were outside, informing the whole camp of their situation. “The army is outside, and we are refusing to leave,” Mohammed’s father Yusuf reportedly said on the air. “Help us.”263

While the queries from IDF legal adviser may have encouraged the soldiers at the Namla house to restrain themselves, they did not compel a change of decision. According to Maj. Noam Neuman, the IDF Deputy Legal Adviser for the Gaza Strip, “I don’t know of cases where legal advisers told commanders not to destroy. Sometimes they call us to tell us they’re going to destroy something. But the IDF knows the law. We don’t stop them because they know what the law is.”264

On July 1, the family fled the house after one of the walls was hit by a bulldozer. Upon returning the next day, they saw that it had been taken over by the IDF; the family found food and water bottles left behind by the soldiers, as well as excrement on the family’s clothes; some U.S. $200 in cash was gone. The building is one of the last ones remaining in the area, but Mohammed, his brother, and father continue to take turns sleeping there at night to prevent its demolition.

Tactics of Destruction

In contrast with the routine operations since 2000 that have gradually expanded the Rafah buffer zone, the May 18-24 incursions involved widespread destruction deep inside Rafah, far from the border. Operating in dense urban areas can present significant risks to militaries, but density is not a reason to disregard international humanitarian law. Human Rights Watch found little evidence to suggest significant or sustained armed resistance to these incursions. Even if there had been fighting, the IDF adopted operational doctrines of destruction that were indiscriminate and disproportionate.

The IDF’s concerns about incoming fire from buildings and improved explosive devices (IEDs) on roads during incursions were not unfounded. Armored vehicles are particularly susceptible to anti-armor weapons when fired from above or behind, targeting areas of minimal armored protection. These vehicles are also susceptible to mines and explosives from below, and Palestinian armed groups were placing IEDs on some of Rafah’s roads.265 In Brazil and Tel al-Sultan, however, the IDF treated this risk in a general manner, assuming every street posed a threat that justified demolishing homes, tearing up roads, and razing agricultural land.

In a military operation, an occupying power must at all times distinguish between civilian objects and military objectives and direct its attacks only against the latter. In cases of doubt as to whether a normally civilian object is a military one or not, it should be presumed to be civilian (see Chapter VIII). Destroying roads on the assumption that they are mined and civilian homes on the assumption that every road around them is mined undermines this rule, and is also likely to result in disproportionate and indiscriminate destruction in densely populated areas. If the IDF had a specific reason to believe that a particular road was unsafe due to IEDs or potential RPG fire, for example, it could take steps to avoid that road and could destroy the road or homes near it only as a last resort. But destruction without even checking for specific threats contravenes the principle of precaution, which requires that militaries do everything feasible to verify that the objectives attacked are not of a civilian character. The principle of precaution also includes the duty to cancel or suspend attacks against nonmilitary objectives or that may be expected to cause disproportionate damage.266

Military commanders on the ground must also assess the proportionality of means and methods they use by weighing the anticipated harm to civilians against the anticipated military gain. The rule of proportionality is intended to avoid and in any event minimize the number of civilian casualties and destruction that derives from hostilities. The widespread destruction of homes and roads used by civilians had a major impact on civilians, while the military gain of such conduct remains hypothetical at best.

Home Demolitions to Enhance Mobility

The IDF destroyed 156 homes in Brazil and Salam and damaged fifty-nine others rendering over 1,900 people homeless. Many of these homes, especially those further from the border, were demolished to provide the IDF with greater mobility and to protect it from attack.

[248] Human Rights Watch interview with Sami Qishta, aged forty, Rafah, July 13, 2004.

[249] Human Rights Watch interview with Mohammed Juma’, Rafah, July 13, 2004.

[250] Tsadok Yehezkeli, “Regards from Hell,” Yediot Ahronoth, June 11, 2004 (Hebrew).

[251] Chris McGreal, “The Day the Tanks Arrived at Rafah Zoo,” Guardian, May 22, 2004.

[252] Human Rights Watch interview with Joachim Paul, UNICEF, Gaza City, July 12, 2004.

[253] Human Rights Watch interview with Mahmoud Nijm, aged fifty-four, Rafah, July 14, 2004.

[254] Human Rights Watch interview with Fariyaal Abu Hamaad, aged fifty-five, Rafah July 15, 2004.

[255] Human Rights Watch interview with Mahmoud Nijm, aged fifty-four, Rafah, July 14, 2004.

[256] Human Rights Watch interview with Mohammed Mansour, Rafah, July 14, 2004.

[257] Human Rights Watch interview with Mahmoud Nijm, aged fifty-four, Rafah, July 14, 2004.

[258] Human Rights Watch interview with Husayn Nijm, aged forty-one, Rafah, July 14, 2004.

[259] Human Rights Watch interview with Subhi Abu Ghali, aged forty-two, Rafah, July 22, 2004. Abu Ghali’s account was also recorded in Chris McGreal, “‘They have no humanity. They didn't even give us two minutes to get out,’” Guardian, June 4, 2004.

[260] “Israeli forces kill Palestinian child,” al-Jazeera.net, May 22, 2004, available at: http://english.aljazeera.net/NR/exeres/8147802B-AB86-4407-9A9C-8A4074359563.htm (accessed August 16, 2004).

[261] “Operation Rainbow to Continue until Objectives are Achieved: Excerpts of address made by Brig. Gen. Shmuel Zakai, Commander of Gaza Division on Monday, May 25 2004,” IDF Spokesperson’s Unit, available at: http://www1.idf.il/dover/site/mainpage.asp?clr=1&sl=EN&id=7&docid=31511. A video clip of the shaft is available at http://www1.idf.il/SIP_STORAGE/DOVER/files/7/31467.wmv.

[262] Human Rights Watch interview with Mohammed Namla, aged twenty-six, July 15, 2004.

[263] Amira Hass, “‘The Army is Outside, and We are Refusing to Leave,’” Ha’aretz, May 24, 2004.

[264] Human Rights Watch interview with Major Noam Neuman, IDF Deputy Legal Adviser for the Gaza Strip, Tel Aviv, July 20, 2004.

[265] Human Rights Watch interview with “Abu Husayn” [pseudonym], al-Quds Brigades, Islamic Jihad, Rafah, July 16, 2004.

[266] First Additional Protocol, Art. 57.

| <<previous | index | next>> | October 2004 |