<<previous | index | next>>

IV. EXPLOSIVE REMNANTS OF WAR

The impact of the war in Iraq on civilians did not end with the conclusion of major hostilities. Staggering quantities of explosive remnants of war continue to endanger civilians as well as military forces.327 The Coalition’s air and ground campaigns littered the country with tens of thousands of unexploded submunitions. These de facto landmines, which can detonate on contact, caused daily casualties in the weeks after the end of active hostilities and present lingering dangers in populated areas and open fields. Iraqi military and fedayeen forces abandoned large caches of weapons and ammunition in schools, mosques, hospitals, and residential neighborhoods. These munitions have killed or injured scores of Iraqis, many of whom are children, searching for scrap metal or playing with explosives. Opposition fighters have also looted the sites and used the ordnance for attacks on Coalition forces and against civilians, such as the deadly truck bombing at the U.N. headquarters in Baghdad on August 19.

The significant and ongoing impact of these explosive remnants of war demonstrates the need for armed forces to consider the post-attack effects of their actions. Belligerents should not use weapons with high dud rates or unnecessarily store weapons caches in civilian areas. After the conflict, they should ensure that unexploded ordnance and landmine locations are marked and cleared as soon as possible and that abandoned munition sites are secured quickly.

Cluster Munitions and the Dangers of Duds

Cluster munitions cause humanitarian harm not only because they are area effect weapons, but also because a large percentage of their bomblets or grenades do not explode on impact.328 These explosive duds remain live and dangerous and are frequently set off by civilians after the strikes. In Iraq, they continue to cause deaths and injuries months after major fighting ended. Human Rights Watch documented hundreds of casualties with site visits, hospital records, and interviews with victims. Duds have also interfered with local agriculture. During the war, they impeded Coalition troop movements, and they have killed Coalition troops both during and after hostilities. The humanitarian and military harm they cause has led even some of the soldiers who fought in Iraq to call for an alternative to a weapon that produces so many duds.

Civilian Harm

The number of submunitions used in Iraq dwarfs that used in Afghanistan or Yugoslavia and has resulted in significant civilian casualties, after as well as during attacks.329 Based on CENTCOM’s reported 10,782 munitions, U.S. forces probably used at least 1.8 million submunitions; an average dud rate of 5 percent would leave about 90,000 duds.330 The U.S. Air Force alone reported dropping about 1,206 cluster bombs containing 237,546 bomblets.331 The British dropped seventy RBL-755 bombs containing 10,290 bomblets.332 Dud rates vary by type of cluster bomb but even a conservative 5 percent dud rate would leave more than 12,000 unexploded bomblets. Ground-launched submunitions, which the Coalition did not use in Afghanistan or Yugoslavia, left even more duds, especially in populated areas. The U.S. Army and Marines have not revealed the number they used, but it is likely to be significantly higher than the number of air-dropped submunitions. In Karbala’ alone, for example, a Marine explosive ordnance disposal team cleared 4,000 duds in less than a month.333 The British reported firing 2,100 artillery-delivered cluster munitions in the area of Basra.334 These L20A1s contained 102,900 grenades with a reported 2 percent dud rate.335 While submunitions have caused civilian casualties in past conflicts, the large quantities used, heavy targeting of urban areas, and deployment of ground as well as air models magnified their impact in Iraq.

Ground-launched submunitions have caused the most post-conflict civilian casualties. Coalition forces used them extensively as part of unobserved counter-battery fire. Since Iraqi forces often occupied populated areas on the edges of towns, the attacks left thousands of duds in urban neighborhoods and villages near the major cities of Iraq.

The post-strike situation in al-Hilla exemplifies the dangers MLRS and artillery duds pose civilians. Dr. al-Falluji at al-Hilla General Teaching Hospital said the city suffered almost daily casualties from clusters in the weeks after battle there.336 From April 1 to April 11, the hospital recorded 221 war-related injuries mostly from duds. The hospital recorded an additional thirty-one injuries attributable to cluster duds from May through August.337

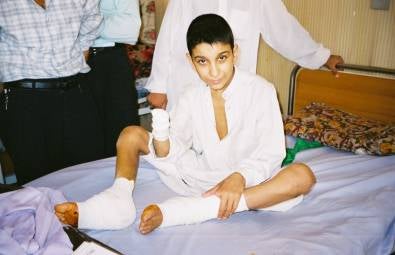

Explosive duds have endangered al-Hilla’s inhabitants since moments after the battle began on March 31. Ambulances could not enter one neighborhood to evacuate wounded civilians because their drivers feared running over a dud in the dark; the next morning hundreds of injured civilians were taken to the hospital.338 Three days later, in the village of al-Maimira, just southeast of town, a dud killed Hussain `Abbas, 30. “He prayed and had dinner and went inside his house,” said `Abbas’s sister. “Suddenly there was an explosion. He called, ‘Rihab’ [the name of his wife] and after that he died.”339 Duds in al-Kifl, a little further south, sent other civilians to al-Hilla Hospital. Thirteen-year-old Falah Hassan was injured by an unexploded DPICM on March 26 and remained in the hospital on May 19 awaiting skin grafts.340 The explosion ripped off his right hand and spread shrapnel through his body. He also lost soft tissue in his lower limbs and his left index finger. His mother, who lay in the hospital bed next to his, suffered injuries to her abdomen, uterus, and large and small intestines from the same explosion.341 In mid-May, long after the battle ended, cluster duds still threatened al-Hilla’s people. A home in the Nadir neighborhood had two live DPICMs on its roof and second-floor terrace. Human Rights Watch also witnessed a young boy pick up a live dud and carry it down the street through a crowd of his neighbors. Fortunately, it did not explode.

Falah Hassan, 13, was injured by an unexploded ground-launched submunition on March 26 and remained in al-Hilla General Teaching Hospital awaiting skin grafts on May 19. The explosion ripped off his right hand and spread shrapnel through his body. © 2003 Bonnie Docherty / Human Rights Watch

Civilians in other cities now occupied by U.S. forces suffered numerous casualties from duds. Al-Najaf Teaching Hospital treated 109 injured civilians, including twenty-eight children, in the week after the main battle for al-Najaf, most of whom were hurt by submunitions.342 Several patients at that hospital described how they were injured and maimed by cluster duds. On March 26, Samir Qassim `Abbas, a 24-year-old taxi driver and college student, went to pick up some passengers in Abu Sukhair, fifteen kilometers (nine miles) east of al-Najaf. “I entered a house where I found something that looked like a piece of lamp. I kicked this thing. When I kicked, it exploded and I fell down,” `Abbas said.343 Two months later, he remained in the hospital. The submunition, which he identified from photographs as a Hydra dud, left him with injuries and bone loss in both legs. The right leg required skin grafts, and his left leg needed surgery to replace his tibia.344 In al-Nasiriyya, three boys were injured by a DPICM at 10:00 a.m. on April 28. Yasir Hamid, 11, suffered mild burns and his brother Hussain Hamid, 7, fractured his leg. Their cousin and neighbor, Mahir Qandil, 11, was also injured.345

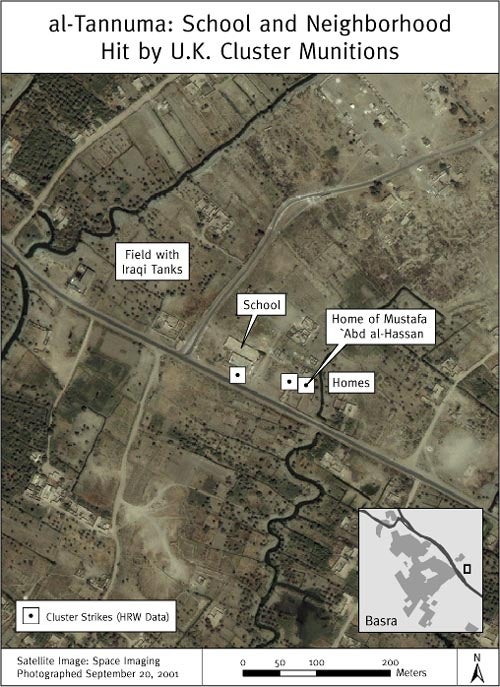

U.K. submunitions posed similar threats in the south. In the Kam Sabil district of Basra, a strike left five duds on the roofs of civilian homes. A 9-year-old girl picked up one of the submunitions causing an explosion that killed her and injured her pregnant mother and 18-month-old brother.346 Although the residents of al-Tannuma did not report any injuries from duds, submunitions from British L20A1s littered their neighborhood in Basra weeks after the war. Mechanic Mustafa `Abd al-Hassan, 45, found three duds in the yard of his home when he returned after the attack.347 The British cleared two, but a third remained at the end of May. It lay at the base of the back wall of his house with only cans of cooking oil to mark its location.

While ground-launched submunitions have caused the overwhelming majority of the post-combat cluster casualties in Iraq, air-dropped cluster bombs have also contributed to the number of civilian deaths and injuries. The latter have caused fewer casualties, in part, because the U.S. Air Force learned a lesson from past wars and limited the number of cluster bombs it used in or near civilian areas. It did make exceptions, however, that left duds in residential neighborhoods. In Baghdad, for example, the U.S. Air Force dropped cluster bombs on a date farm in Hay Tunis. The Iraqi military had used the grove to hide military vehicles, thus making it a legitimate target for the United States, but immediately across the street, on at least two sides, were densely populated residential areas. Two days after the attack in early April, Hussam Jasmi, 13, and Muhammad Mun`im Muhammad, 14, cousins who lived a few minutes away from the farm, stepped on a BLU-97 submunition. The bomblet ripped off their legs and ultimately killed them.348 The U.S. military came to clear the farm around May 13, but later that week, Human Rights Watch still found bomblets on the site.

Map 07

Download PDF (1.6 Mb)

Unexploded bomblets also endanger civilians in more rural areas. Najat Khalid lost her two sons to BLU-97s in the village of Sichir near al-Falluja. Neighbor Kayun Risham, 50, was injured.349 Military vehicles located near the farms where they lived may have been legitimate military targets. The large number of duds left by the weapon chosen, however, unnecessarily endangered civilians.

Children are particularly vulnerable to unexploded submunitions, regardless of the type. “Bomblets are what kids pick up. There is a nice ribbon on the end [of a DPICM]. It’s nice for carrying,” said an officer at the Baghdad Civil-Military Operations Center (CMOC).350 `Abbas Hussain, 12, for example, lost half of his hand to a cluster grenade. “He picked up something in the road. He thought it was something to play with, but it hit the ground and exploded,” said Hussain’s uncle Hossam al-`Alawi during an interview at al-Najaf Teaching Hospital. To make matters worse, Hussain is a hemophiliac.351 Doctors around Iraq agreed that children were the most common victims of cluster duds. “Cluster bombs sometimes look like beautiful things. Children like to play with them. [The duds] are here and there, everywhere on farmland. They look shiny,” said Dr. al-`Ubaidi at al-Najaf Teaching Hospital.352 Hospital records provide additional evidence of this trend. Fifty-six children (25 percent of the casualties) were injured in al-Hilla in April; twenty-eight children (26 percent of the casualties) were injured the first week after the battle of al-Najaf.

Abandoned Iraqi submunitions have also endangered civilians. According to the CMOC officer in Baghdad, cluster casualties were caused by a “combination of the ones we fired and Iraqi artillery stores spread around.” He said U.S. troops had encountered KB-1s, a Yugoslavian version of a DPICM submunition, left by the Iraqis.353 Some of these submunitions may have been ejected when their canisters were hit by fire. In al- `Amara, near Basra, six people died from such ordnance. “Kids were playing with Iraqi MLRS,” said Warrant Officer 1 Nick Pettit of the British Joint Force EOD Group.354

Duds from Coalition cluster munitions not only cause civilian casualties but also interfere with agriculture and the economic recovery of Iraq. Both air- and ground-launched cluster munitions litter fields along the battle route to Baghdad. The U.S. Air Force dropped CBUs on an Iraqi military position across from the Agargouf ziggurat. The field contained an SA-3 surface-to-air missile battery and radar truck. In May, dozens of unexploded BLU-97 bomblets still covered the field, some lying in ditches where they had fallen or been placed by locals, others buried in the ground after piercing the soft surface on impact. While Human Rights Watch was investigating the site, a shepherd, apparently oblivious to the danger, walked through with a flock of about forty sheep and goats. They grazed among the bomblets, and one goat nibbled grass with a BLU between its legs. About half an hour later, while at another part of the site, the Human Rights Watch team heard a large explosion from the cluster bomb field, possibly a bomblet set off by one of the animals.

Cluster grenades interfere even more with agriculture. DPICMs and ATACMS submunitions littered farmland in the month after the war, and in some places, like Agargouf, were found in close proximity to air-dropped bomblets. “We have to burn the fields. There are still bombs there. We are growing grains for our animals,” said the father of Falah Hassan, the submunition victim from al-Kifl.355 In May, Human Rights Watch found fields contaminated with submunitions in villages around al-Hilla, al-Najaf, al-Falluja, and Agargouf.

Adverse Military Consequences

While the broad footprint of a cluster munition has military value, the numerous duds do not. These unexploded submunitions are not intentionally left behind; they fail to explode as designed. In Iraq, cluster duds not only decreased the effectiveness of the weapon against enemy troops but also endangered Coalition troops and interfered with some military operations.

Unexploded submunitions have killed at least five members of the Coalition military. On March 27, Marine Lance Corporal Jesus A. Suarez del Solar, 20, died after stepping on an unexploded submunition in a field near Baghdad.356 A few weeks later on April 19, an Iraqi girl handed Army Sergeant Troy Jenkins of the 101st Airborne Division a cluster grenade, which exploded injuring several soldiers in the area. Jenkins, 25, died from his injuries four days later.357 The United Kingdom has also lost troops to unexploded submunitions. Lieutenant Colonel Shanahan of the British Joint Force EOD Group reported that three soldiers were killed while clearing submunitions in Basra. A fourth suffered injuries from a cluster grenade that exploded fifty meters (fifty-five yards) away from him.358

Duds have also interfered with some military operations. Colonel Baldwin of the Queen’s Dragoon Guards encountered a field of DPICMs west of Umm Qasr, 500 meters (.3 miles) north of the Kuwaiti border. “The first night [of the war], the lead vehicle of our convoy walked straight into a cluster bomb field. The corporal came out white faced. . . . It took half an hour to get out,” he said.359 In some cases, units chose not to use cluster munitions because they knew their own troops would have to cross a field littered with duds.360 Such incidents demonstrate how cluster munitions can be detrimental to the military as well as civilians. Reducing the dud rate is thus a place where military necessity and humanitarian concern coincide.

New Technology

Both the United States and United Kingdom deployed new types of cluster munitions in Iraq that are designed to reduce the dud rate. The U.S. Air Force dropped the CBU-105 Sensor Fuzed Weapon for the first time in combat. This weapon, eighty-eight of which were used, employs the Wind Corrected Munitions Dispenser. It contains ten BLU-108 submunitions, each of which releases four skeet warheads, the size of hockey pucks, with infrared sensors.361 To reduce the dud rate, the submunitions have self-destruct mechanisms.362 Human Rights Watch visited one site outside of al-Hilla where the United States had dropped CBU-105s on an isolated field of artillery. No unexploded skeets were visible although some could have been hidden in the tall grass. The CBU-105 Sensor Fuzed Weapon is a potentially significant development that attempts to address key humanitarian problems associated with cluster weapons: accuracy of both the munition and submunition and dud rates. Further investigation should be done to calculate its dud rate in actual combat operations and determine if it meets its design standards in practice.

The United States also for the first time used two CBU-107s, which contain 3,700 non-explosive rods. It dropped them on the Ministry of Information in order to destroy rooftop antennae. This weapon has the advantage of not leaving explosive duds. Further investigations should be done to determine its overall humanitarian effect.

In a U.K. combat first, British forces used the L20A1, an artillery shell with M85 submunitions similar to U.S. DPICMs but with self-destruct mechanisms.363 The submunition has a dud rate of 2 percent, according to the British Ministry of Defense.364 If that rate occurs in actual combat, it would be an improvement over the U.S. model, which has a reported 14 percent dud rate.365 Human Rights Watch could not determine the rate from the field, but it did find evidence of duds from L20A1s in multiple areas of Basra. In al-Tannuma, for example, three unexploded submunitions lay in Mustafa `Abd al-Hassan’s yard when he returned to his home the morning after the strike. One of those had been buried under garbage and missed by British EOD teams; it was still in his yard on May 30.366 Other civilians in the neighborhood reported duds left by the attack. Tha’ir Zaidan, 25, said, “I carried one in my hand across the street. I set it down carefully and made a sign. It was between my kids. I had no choice.”367 He found another grenade in his house. Across Shatt al-`Arab river, U.N. deminers found a grenade that was probably from an L20A1 on the roof of their new headquarters, in a clearly populated area.368 Ironically the promise of a lower dud rate may have made the British less careful about where they used the L20A1. “There was less of a reluctance to use them because of the increased reliability,” Colonel Baldwin said.369 Efforts to reduce the dud rate of cluster munitions should be commended; however, the rates must be made significantly lower and cluster munitions must be kept out of populated areas if humanitarian harm is to be minimized.

Despite the availability of new technology, the Coalition continued to use old cluster munitions with high dud rates. The U.S. and U.K. air forces both dropped versions of the Vietnam-era Rockeye. The weapon had been used extensively in the 1991 Gulf War and its duds are still being cleared. While no reliable estimate of the failure rate is available, clearance agencies in Kuwait encountered a very large number of dud Rockeye submunitions in their operations.370 One U.S. company reported clearing 95,799 Mk-118 Rockeye duds in its sector of Kuwait, which constituted 18 percent of the total area cleared.371 In 2002, 451 Rockeye duds were detected and destroyed by mine clearance and explosive ordnance disposal teams in Kuwait.372

Growing Opposition to Cluster Munitions

The humanitarian harm and military impediments caused by cluster munition duds compelled even Coalition forces in Iraq to join those who question use of the weapon. International concern about submunitions’ negative impact on civilians has increased steadily in recent years.373 Human Rights Watch, for example, called for a moratorium on use of cluster munitions until the humanitarian concerns associated with the weapon are addressed.374 Responding to external and internal pressure, the U.S. Air Force, which used cluster bombs in the 1991 Gulf War, Yugoslavia, and Afghanistan, has modified its practices to reduce, although not eliminate, the weapons’ impact on civilians. For example, it dropped fewer cluster bombs in populated areas and used primarily newer models. The war in Iraq was the first in a decade to involve large numbers of U.S. and U.K. ground forces. Their combat experiences with artillery and MLRS submunitions led some soldiers and Marines to call for an alternative weapon with fewer deadly side effects.

Several Army and Marine officers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they felt uncomfortable using a weapon that produced so many duds and called for the development of a better alternative. “We have to demand giving commanders better options,” said Lieutenant Colonel Stephen Baer, operations officer for the Third Infantry Division, noting the danger duds pose to soldiers passing through the strike areas.375 Leaders of the division’s Second Brigade expressed a reluctance to use cluster munitions. “We had concerns about unexploded ordnance. . . . It’s a constant consideration. What are the second or third effects?” said commanding officer Colonel Perkins.376 In some cases, his brigade sought less harmful alternatives. When calling for close air support, he said it preferred JDAMs or an A10 “Warthog” with tank-killing close air support. In Baghdad, it used high explosive artillery airbursts over highway clover leafs to reduce damage to the roads. For longer-range ground support, however, the MLRS is “the only type of munition we have.”377 The MLRS, which uses submunitions exclusively and has a dud rate of 16 percent,378 was the only weapon available at the divisional level with a range of thirty-two kilometers (twenty miles), or if an extended range model, forty-five kilometers (twenty-eight miles). When the division offered it, however, “we wouldn’t always use it,” Perkins said.379

A post-conflict lessons learned presentation by the Third Infantry Division echoed the concerns of its field officers. The division described dud-producing submunitions, particularly the DPICM, as among the “losers” of the war. “Is DPICM munition a Cold War relic?” the presentation asked. The dud rate of the DPICM, which represented more than half of its direct support battalion’s available arsenal, was higher than expected, especially when not used on roads. Commanders were “hesitant to use it . . . but had to.” The presentation specifically noted that these weapons are “not for use in urban areas.”380

Marines in the field also complained about the aftereffects of submunitions. “The biggest UXO [unexploded ordnance] problem is clusters because they are extremely sensitive and were used extensively. We wouldn’t use cluster bombs in battle even if it degraded [our capacity],” said one Marine on condition of anonymity.381 The development of an alternative to cluster munitions would protect the lives of both civilians and soldiers. It would also decrease the cost of clearing duds after the conflict.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The aftereffects of cluster munitions raise concerns under international humanitarian law. As explained above, an attack will be unlawfully disproportionate if it “may be expected to cause incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians, damage to civilian objects, or a combination thereof, which would be excessive in relation to the concrete and military advantage anticipated.”382 If this proportionality test is interpreted as encompassing more than immediate losses, the large number of explosive duds may make cluster munition use disproportionate. Taking into account both strike and post-strike casualties greatly increases the likelihood that the loss would be excessive in relation to the military advantage, especially if an attack occurred in a populated area or an area to which people might return. The U.S. Air Force has said that the dud rate must be part of the proportionality determination because unexploded bomblets are “reasonably foreseeable.”383

Because of their duds, cluster munitions also exemplify weapons that can be indiscriminate in effect. Indiscriminate attacks include those that “employ a method or means of combat the effects of which cannot” distinguish between military targets and civilian objects.384 Even if a cluster munition strike is not indiscriminate, its effects may be. The effects become more dangerous if the submunitions litter an area frequented by civilians or the dud rate is high due to poor design, use in inappropriate environments, or delivery from a high altitude. Cluster duds cannot distinguish between combatants and civilians and will likely injure or kill whoever disturbs them. Under either the proportionality test or the indiscriminate effects provision, the high dud rate of cluster munitions combined with the large number of submunitions they release challenges the principle of distinction.

As discussed above, states are required to minimize civilian harm. Given the potential indiscriminateness discussed above, the United States, and other countries that use cluster munitions, should avoid strikes in or near populated areas and minimize the long-term effects of duds.385 The availability of alternative weapons should also be considered.

The situation in Iraq highlights the need to suspend the use of cluster munitions until the dud rate is dramatically reduced. Although the proportionality test necessitates a case-by-case analysis, in general, the extensive aftereffects of Coalition cluster grenades in or near populated areas call for close scrutiny under this provision. The large number of duds and their serious and long-term impact on civilian life and livelihoods also suggest that at least some models of submunitions, when used in or near populated areas, are indiscriminate in effect. Finally, the United States and others may not have taken “all feasible precautions” to reduce the dud rate. The British use of L20A1sshows that self-destruct weapons are available for use in the field, and on paper, the United States has recognized the value of that technology. In 2001, the U.S. Secretary of Defense William Cohen stated that all future submunitions must have a dud rate of less than 1 percent.386 In August 2003, General Richard Myers, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said the Army planned to use self-destruct fuzes on some DPICMs in 2005.387 In the meantime, however, the United States littered Iraq with outdated, unreliable submunitions. Militaries planning for future battles in urban or populated areas must consider changes in targeting and technology that will make the use of cluster munitions less problematic.

To address the dangers of cluster munition duds, Human Rights Watch recommends that:

- The use of submunitions should be suspended until the initial dud rate can be reduced dramatically, at least to less than 1 percent.

- Whatever the dud rate, armed forces should consider the long-term effects of cluster munitions when choosing targets. Cluster munitions should not be used in populated areas where the risk of civilian casualties from duds increases.

- The United States, the United Kingdom, and others should continue efforts to improve the reliability of submunitions. They should also consider if weapons with fewer humanitarian side effects can replace them.

- To facilitate post-conflict clearance of duds, armed forces, especially U.S. ground forces, should improve their recording of cluster strikes and share that information with deminers and the public.

Abandoned Explosive Ordnance

As they retreated from the Coalition advance, Iraqi forces abandoned massive quantities of explosive ordnance that they had stored in populated residential areas. These arms and ammunition—most outdated and many unstable—caused scores of civilian casualties both during combat operations and afterwards, and they continue to endanger the civilian population today. The abandoned explosive ordnance has presented deadly temptations to children looking for entertainment and adults searching for goods to use or sell. It has also served as a munitions source for those opposing the Coalition, some of whom have targeted civilians. U.S. and British forces failed to secure or clear these abandoned munition sites in a timely fashion, most notably in Basra and Baghdad, and thus bear some of the responsibility for the numerous civilian deaths and injuries. During the remainder of their occupation of Iraq and in similar situations in the future, Coalition forces should prioritize securing abandoned munitions for the safety of the local population, international aid and U.N. workers, and their own troops.

There may be more than 600,000 tons of abandoned munitions throughout Iraq, according to the director general of the National Mine Action Authority in Iraq.388 Coalition troops repeatedly remarked on the extent of the abandoned munition problem in Iraq. “We inherited a city full of ordnance,” said a CMOC officer in Baghdad. “The big problem in terms of quantity is not bomblets, but crates and crates of explosive ordnance.”389 Lieutenant Colonel TimEverhard of the U.S. Third Ordnance Battalion, who wasin charge of Coalition clearance efforts in the capital, echoed this statement. He said his teams had received reports of 400 caches in Baghdad alone. “We are finding everything. You can’t swing a dead cat in Baghdad without hitting an RPG,” Everhard said.390 While unguarded caches represent the biggest humanitarian threat, isolated explosive ordnance also litters the country. Human Rights Watch found a stray RPG in the middle of a Baghdad traffic circle at the foot of the statue of King Faisal.

The situation in the British sector in southern Iraq is similar, if not worse. “I’ve never seen so much ordnance, and I’ve been in the Balkans, Northern Iraq, and Afghanistan,” said CMOC representative John Thompson.391 Lieutenant Colonel Shanahan said he was “astounded by the amount of ordnance.”392

Iraqi forces kept many of their stockpiles in or near populated areas, which magnified the danger to civilians. “It’s hard. There are ammunition supply points in neighborhoods, in basements, in backyards. The condos by the airport are full of ordnance,” Lieutenant Colonel Everhard said.393 A representative from an international relief organization said he visited thirty schools in Basra and encountered abandoned stocks “everywhere.”394 Near al-Maqal Airfield in Basra, Human Rights Watch found a sprawling, unsecured storage facility a half kilometer (.3 miles) from residential neighborhoods. It included twenty-six partially buried shipping containers housing millions of rounds of anti-aircraft ammunition, thousands of anti-ship rounds, hundreds of air-to-air helicopter rockets, and hundreds of RPGs. Ironically, the Iraqi military could not use much of this ordnance. Most of it was old or incompatible with more recent Iraqi weapons; because it dates to the Soviet era, it lacks the safety designs of more modern munitions.395

Iraqi forces abandoned this unsecured weapons cache near al-Maqal Airfield in northwest Basra. The munitions were strewn about by civilians trying to salvage scrap metal. Parts of this site spontaneously combusted in 120 degree Fahrenheit heat days after this photo was taken. © 2003 Marc Garlasco / Human Rights Watch

While stockpiling munitions in populated areas is part of urban warfare, Iraqi military and fedayeen stored their weapons in civilian buildings. “Ninety percent of their caches were stuck in hospitals, schools, and mosques,” Lieutenant Colonel Everhard said. Fedayeen, for example, occupied the Surgical Hospital in al-Nasiriyya during the war. Hours after surrounding the building, U.S. Marines took 170 Iraqis captive and found 200 weapons, boxes and boxes of ammunition, 3,000 chemical warfare protection suits, and a tank in the hospital compound, officers said.396 In early April 2003, Human Rights Watch learned that Iraqi forces had stored landmines inside a mosque in Qadir Karam in northern Iraq and laid mines around the mosque before abandoning it. The Mines Advisory Group removed 1,077 antivehicle and antipersonnel mines from the site.397 Human Rights Watch documented similar reports of munitions stored in hospitals and mosques from other troops involved in clearance of these sites.398

Dangers to Civilians

Abandoned Iraqi munition caches have caused significant civilian casualties. Many Iraqis try to scavenge scraps from such caches that they can then use at home or sell on the market. In some cases, they empty crates of ammunition for firewood and leave explosive ordnance spread across a site. In other cases, they remove the warheads of artillery shells in order to collect brass casings or gather propellant for fuel.399 Both activities threaten the lives and limbs of the scavengers and leave explosive remnants that endanger future passersby.

Human Rights Watch found evidence of looting in regions occupied by U.S. and U.K. troops. In Karbala’, during the third week of May, locals were scavenging at a fedayeen training center when an explosion collapsed the building, killing four civilians. “Sites like this will be a long-term problem,” said Major Samarov. “Now the building is functionally booby-trapped.”400 At the Basra storage facility, looters left propellant strewn across the site and warheads lying in the open. Four days after Human Rights Watch’s visit, one of the containers of unsealed ordnance “cooked off” with a huge explosion.401 In Iraq’s summer heat, scattered munitions do not need human intervention to detonate.

Children are frequent victims of abandoned munitions. On May 9 in Baghdad, Muhammad Keun Jiheli, 16, brought a piece of ordnance home to use for cooking fuel. An explosion killed four members of his family. He suffered burns over 72 percent of his body, and Jamil Salem Hamid, also 16, received burns over 54 percent of his body.402 Munition caches also endanger children who think that lighting propellant is a game. Bill Van Ree of the U.N. Mine Action Coordination Team (UNMACT) said he saw “young men” throwing matches on spilled ordnance in Basra and “having a great time.”403 At 2:00 p.m. on May 3, eight-year-old `Ali `Abdul-Amir put a match to a piece of explosive ordnance outside a school in al-Hay al-`Askari, a neighborhood of al-Nasiriyya. The explosion left him with burns and shrapnel injuries.404 Human Rights Watch witnessed children playing among munitions and propellant at the large cache in Basra.

Eight-year-old `Ali `Abdul-Amir suffered severe burns and shrapnel injuries when he put a match to a piece of explosive ordnance outside his school in al-Nasiriyya. © 2003 Reuben E. Brigety, II / Human Rights Watch

Iraqi ammunition caches also endanger civilians because the materiel in arms caches is often still viable weaponry. At 4:45 p.m. on August 19, a truck bomb exploded at the Canal Hotel, the U.N. headquarters in Baghdad. The attack killed twenty-two civilians and injured scores more, including U.N. staff from Iraq and abroad and nongovernmental organization (NGO) visitors. Sergio Vieira de Mello, the U.N. special representative in Iraq and U.N. high commissioner for human rights, was among the dead. Investigations after the fact showed that the bomb had been made from old munitions.405 The U.N. bombing was not an isolated incident. Ten days later, another blast, this time from a bomb in a van, killed ninety-one people at the Imam `Ali Shrine in al-Najaf. Investigators reported that this attack was “fueled with Soviet-era munitions likely scavenged from weapons depots belonging to the former Iraqi army.”406 Such attacks not only kill innocent Iraqis. They also threaten the future of humanitarian aid operations in Iraq. After the U.N. attack, 120 NGOs pulled out some of their staff, and the ICRC cut its international staff by two-thirds.407 The number of U.N. foreign employees dropped from 600 before the attack to sixty by October 1.408 Additional attacks on civilian targets, including the ICRC, led the United Nations to withdraw its entire international staff from Baghdad409 and the ICRC to close its offices in Baghdad and Basra.410

It is likely that those opposing the Coalition forces have also used these abandoned stockpiles to launch attacks. Since President Bush announced the end of major hostilities on May 1, both U.S. and U.K. forces have faced frequent attacks. As of November 11, 171 Coalition troops had died from hostile attacks after the end of major hostilities, more than the 142who died during active combat.411 It is unclear where those opposing the Coalition obtain their weapons and ammunition, but the abandoned munition caches are one likely source. Securing and clearing them is therefore an area where military and humanitarian concerns coincide.

Protection of Civilians

The United States and United Kingdom have a duty as occupying powers to protect the Iraqi people. With respect to abandoned explosive ordnance, this duty means securing sites immediately and clearing them as soon as possible. At the time of the Human Rights Watch mission, clearance was proceeding slowly but steadily while efforts to secure the sites were minimal.

The first priority for dealing with abandoned ordnance should have been securing sites. Keeping civilians away from caches, particularly large ones like the site in Basra that Human Rights Watch visited, removes the temptation to search for scraps or playthings and helps protect civilian lives. It also ensures that the ordnance does not end up in the hands of those that threaten both civilians—local and foreign—and Coalition troops. Finally, properly securing explosive ordnance sites facilitates later clearance by keeping the ordnance in its proper containers.

Human Rights Watch’s investigation showed that six weeks after the end of major hostilities, the Coalition’s efforts in this area were still inadequate. A Human Rights Watch researcher found large unsecured ammunition stocks at the Second Military College north of Baghdad, including rooms filled with antitank mines, antipersonnel mines, mortars, and large stockpiles of multiple rocket launcher rocket heads. At the request of internally displaced persons living on the grounds, the researcher reported the stockpiles to U.S. military authorities in Baghdad, who promised immediate attention to the issue. For the next ten days, the researcher continued to report the find, yet the weapons remained unsecured, and the displaced persons reported that no U.S. military authorities had visited the college. It took nearly two weeks after the stockpile was initially reported for U.S. military authorities to send a response team. Despite the delays in some cases, U.S. forces recognized the need to attend to unguarded sites. In Karbala’, Marine EOD team leader Gunnery Sergeant Tracey Jones said his team secured two “huge ammunition supply points” by building berms on four sides and blocking the doors.412

The British forces in Basra made little or no effort to secure the large sites near its posts in the city. The storage facility Human Rights Watch visited was about 600 meters (.4 miles) from the headquarters of the First Fusiliers Battle Group. According to a briefing by Lieutenant Colonel Alan Butterfield on May 3, the British had no plans to secure the sites because of a lack of manpower.413 Human Rights Watch criticized this failure in a May 6 press release.414 At the time, Basra’s al-Jumhuriyya Hospital was receiving five victims a day from unsecured ordnance.415 A month later, little had changed. The storage facility remained unsecured, and the U.K. forces were handing over clearance responsibility to UNMACT.

Iraqi looters have interfered with efforts to secure and clear sites. “If you put up extensive fencing, they just take it away,” Lieutenant Colonel Shanahan said.416 Instead his team resorted to waist high signs, twenty meters (sixty-five feet) apart, with red triangles. The looters also break open containers left secure by the Iraqi military. UNMACT’s Van Ree said, on May 27, “[w]e walked away from [a cache near Basra] because the locals were ratting out [scattering] propellant while we were there.”417 The next day he visited a site with sixteen shipping containers of ammunition within 150 meters (.1 miles) of homes. “The problem in this case was that people broke open [the containers] and spread [the ammunition] around,” he said.418

The Coalition’s treatment of munitions caches also suffered from a shortage of clearance experts, but that should not have affected its ability to secure sites. A senior CENTCOM official said that many of its EOD teams had been in Afghanistan for a year and a half. “We tapped out every unit that was in existence. My assessment is it was not enough,” he said.419 The Coalition, however, did not need specially trained EOD experts to secure sites. To speed up efforts, regular soldiers could provide security for abandoned munition caches.

Conclusion and Recommendations

By placing stockpiles of weapons and ammunition in civilian dwellings and schools and other protected locations, such as mosques and hospitals, Iraq rendered these otherwise protected sites potential military targets vulnerable to attack and put the local civilian population at risk.

This conduct violated various rules of international humanitarian law that aim to shield civilians from the effects of hostilities. These provisions include the rule on precautions that requires parties to a conflict “to the maximum extent feasible. . . avoid locating military objectives [such as stocks of weapons] within or near densely populated areas.”420 More specifically, IHL prohibits the use of places of worship, such as mosques, in support of the military effort, including by using them to store weapons.421 Hospitals lose the protection from attack to which they are entitled if they are used to commit “acts harmful to the enemy.”422 Moreover, “medical units,” which include hospitals, may not be used to “shield military objectives from attack.”423 While not explicitly illegal under international law, the placement of ordnance caches in schools and residential neighborhoods also increased the risk to civilians because they had greater access to the munitions once the military fled.

As occupying powers, the United States and United Kingdom have an obligation under international law to protect Iraqi civilians. According to Article 43 of the Hague Regulations, an occupying power “shall take all the measures in his power to restore, and ensure, as far as possible, public order and safety.”424 Abandoned munitions are currently one of the biggest threats to civilians. Looters and children endanger themselves and others when they break apart ordnance and spread the contents on the ground. Opposition forces have also used the explosives to launch attacks on civilians. To prevent further casualties and ensure public safety, the Coalition must secure remaining sites immediately and make sure they are cleared in the long run.

Although there is no existing treaty governing the handling of abandoned weapons caches, the States Parties to the Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW) are negotiating a protocol on explosive remnants of war. The draft protocol reflects the international community’s concern with unexploded ordnance and abandoned explosive ordnance.425 It imposes duties on the state in control of the territory to clear and secure this ordnance. In the technical annex, it also encourages states that abandon ordnance to leave it “in a safe and secure manner.”426 This draft protocol is still under negotiation, but it lays down minimum standards for handling abandoned explosive ordnance, which have been largely unmet in Iraq. The Iraqis did not leave their caches secure, and the United States and United Kingdom did not take “all feasible precautions” to protect civilians when they failed to secure sites.427

Iraq and the United States and United Kingdom share responsibility for casualties caused by abandoned munition caches. Iraqi forces placed these caches in areas where civilians could potentially gain access and injure themselves. The United States and United Kingdom failed to secure the sites once they were in control of the territory. As a result, locals were injured or killed and clearance problems were exacerbated.

To address these issues in the future, Human Rights Watch recommends:

- Armed forces should avoid storing large caches of weapons and ammunition in populated areas and civilian buildings. Under no circumstances should caches be stored in hospitals or places of worship.

- Armed forces that expect to be in the position of occupying powers should do more pre-war planning for security of abandoned explosive ordnance.

327 Explosive remnants of war include all types of unexploded ordnance, which is ordnance that has been used but failed to explode, like cluster munition duds, and abandoned explosive ordnance, which has been left behind by parties to a conflict but not used. This chapter focuses on cluster munition duds and abandoned ordnance and does not address other types of ERW.

328 Air-dropped submunitions are often called bomblets. Ground-launched submunitions are often called grenades.

329 During their air campaign in Yugoslavia from March to June 1999, NATO forces dropped about 1,765 cluster bombs containing about 295,000 bomblets. In Afghanistan between October 2001 and March 2002, the U.S. Air Force dropped about 1,228 cluster bombs containing 248,056 bomblets. Human Rights Watch, “Fatally Flawed,” pp. 41, 1.

330 For an explanation of how these numbers were calculated, see Ground-Launched Cluster Munitions section in the Conduct of the Ground War chapter above.

331 “Operation Iraqi Freedom—By the Numbers,” p. 11. As explained above, the United States also used JSOWs and TLAMs, which can contain submunitions, but it did not report how many of the ones used in Iraq carried that payload.

332 U.K. Ministry of Defence, “Operations in Iraq—First Reflections.”

333 Human Rights Watch interview with Gunnery Sergeant Tracey Jones.

334 Ann Treneman, “Mapped: The Lethal Legacy of Cluster Bombs.”

335 Thomas Frank, “Officials: Hundreds of Iraqis Killed by Faulty Grenades” (citing the British Ministry of Defence).

336 Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. Sa`ad al-Falluji.

337 Al-Hilla General Teaching Hospital, War-Related Casualty Records.

338 Human Rights Watch interview with Hussain Jabir, director, Civil Defense, al-Hilla, May 21, 2003.

339 Human Rights Watch interview with sister of Hussain `Abbas, al-Maimira, May 20, 2003.

340 Human Rights Watch interview with Falah Hassan, al-Hilla, May 19, 2003. The explosion injured three relatives, including his mother.

341 Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. Sa`ad al-Falluji.

342 Al-Najaf Teaching Hospital, War-Related Casualty Records, obtained by Human Rights Watch, al-Najaf, May 24, 2003.

343 Human Rights Watch interview with Samir Qassim `Abbas, al-Najaf, May 24, 2003.

344 Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. Muhammad Hassan al-`Ubaidi.

345 Human Rights Watch interview with Hamid `Atshan, al-Nasiriyya, May 7, 2003. `Atshan, 36, is the father of Yasir and Hussain Hamid.

346 Human Rights Watch interview with international aid worker #2, Basra, May 1, 2003.

347 Human Rights Watch interview with Mustafa `Abd al-Hassan, Basra, May 30, 2003.

348 Human Rights Watch interview with Muhammad `Abd Mamon, Baghdad, May 17, 2003. Mamon, 32, was the uncle of the two boys.

349 Human Rights Watch interview with `Abdul-Runaima, Sichir, May 14, 2003. Runaima, who lives on the chicken farm where CBU-103s were dropped, is the brother of Risham and neighbor of Khalid.

350 Human Rights Watch interview with CMOC officer, Baghdad, May 13, 2003.

351 Human Rights Watch interview with Hossam al-`Alawi, al-Najaf, May 24, 2003.

352 Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. Muhammad Hassan al-`Ubaidi.

353 Human Rights Watch interview with CMOC officer.

354 Human Rights Watch interview with Warrant Officer 1 Nick Pettit, Joint Forces EOD Group, 33 Engineers Regiment, Corps of Royal Engineers, British Army, Basra, May 28, 2003.

355 Human Rights Watch interview with father of Falah Hassan, al-Hilla, May 19, 2003.

356 Blanca Gonzalez, “Mexican-Born Marine Killed near Baghdad to Be Buried in Peace, Father Says,” Copley News Service, April 4, 2003; “Father of Slain Soldier Leads Anti-War Rally; Man Says Latinos Need More Opportunities outside Military,” Associated Press, May 24, 2003.

357 Valerie Alvord, Debbie Howlett, and Tom Kenworthy, “Lingering Dangers Claim Four in Iraq,” USA Today, April 29, 2003; Thomas Frank, “Officials: Hundreds of Iraqis Killed By Faulty Grenades.” The press reported several different versions of the story, and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Richard Myers denied that the ordnance was a submunition. Jenkins’ fellow soldiers, however, told a reporter in September they believed it was a DPICM because of the ballistic evidence they found at the scene. They also had been clearing one hundred DPICMs a day at the time of the accident. E-mail message from Paul Wiseman, USA Today, to Bonnie Docherty, Human Rights Watch, September 10, 2003.

358 Human Rights Watch interview with Lieutenant Colonel John Shanahan.

359 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Colonel Gil Baldwin.

360 Human Rights Watch interview with U.S. Marine officer #2, Iraq, May 2003.

361 As discussed in the Conduct of the Air War chapter, the CBU-105 has a WCMD guidance system to increase accuracy, and each individual skeet has an infrared sensor to target armored vehicles.

362 Global Security.org, “BLU-108/B Submunition,” January 19, 2003, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/munitions/blu-108.htm (retrieved October 22, 2003).

363 The Israelis have already used this munition in southern Lebanon.

364 Thomas Frank, “Officials: Hundreds of Iraqis Killed by Faulty Grenades” (citing the British Ministry of Defence).

365 U.S. Army Defense Ammunition Center, Technical Center for Explosives Safety, “Study of Ammunition Dud and Low Order Detonation Rates,” p. 9.

366 Human Rights Watch interview with Mustafa `Abd al-Hassan.

367 Human Rights Watch interview with Tha’ir Zaidan.

368 Human Rights Watch interview with Bill Van Ree, team leader, U.N. Mine Action Coordination Team (UNMACT), Basra, May 29, 2003.

369 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Colonel Gil Baldwin.

370 Colin King, “Explosive Remnants of War: A Study on Submunitions and Other Unexploded Ordnance,” report commissioned by the ICRC, August 2000, pp. 16, E-2; U.S. General Accounting Office, “Military Operations: Information on U.S. Use of Land Mines in the Persian Gulf War,” GAO-02-1003, September 2002, p. 27. A Department of Defense report to Congress in 2000 cites a 98 percent submunition reliability rate for the Rockeye submunition—a claim not supported by the Kuwait evidence. Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, “Unexploded Ordnance Report,” table 2-3, p. 5.

371 U.S. Army Armament, Munitions, and Chemical Command, “Contract DAAA21-92-M-0300 Report by CMS, Inc.,” n.d.

372 Compiled from Kuwait Ministry of Defense, “Monthly Ammunition and Explosive Destroyed/Recovery Reports,” December 2001-December 2002, Annex A.

373 For a discussion of the public debate about cluster bombs in Afghanistan, see Human Rights Watch, “Fatally Flawed,” pp. 16-19.

374 Human Rights Watch, Memorandum to Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW) Delegates.

375 Human Rights Watch interview with Lieutenant Colonel Stephen Baer.

376 Human Rights Watch interview with Colonel David Perkins.

377 Ibid.

378 Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, “Unexploded Ordnance Report,” table 2-3, p. 5.

379 Human Rights Watch interview with Colonel David Perkins.

380 Third Infantry Division, “Fires in the Close Fight: OIF [Operation Iraqi Freedom] Lessons Learned.”

381 Human Rights Watch interview with U.S. Marine officer #2.

382 Protocol I, art. 51(5)(b).

383 U.S. Air Force, Bullet Background Paper on International Legal Aspects Concerning the Use of Cluster Munitions.

384 Protocol I, art. 51(4)(c).

385 Human Rights Watch, “Fatally Flawed,” p. 12.

386 Secretary of Defense William Cohen, Memorandum for the Secretaries of the Military Departments, Subject: Department of Defense Policy on Submunition Reliability (U), January 10, 2001.

387 General Richard B. Myers, Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff, to Senator Patrick Leahy, August 11, 2003. Myers said the U.S. Army plans to add a self-destruct fuze to the 155mm extended range DPICM in 2005. It “is also developing a self-destruct fuze to reduce the dud rate to below 1 percent for its cluster munitions in rocket and other cannon artillery systems. This new fuze may be available for future production of Army cluster munitions as soon as 2005.” Ibid.

388 “Letter from the National Mine Action Authority in Iraq, by Siraj Barzani, Director General, October 9, 2003,” printed in Mine Action Support Group October Newsletter, New York, October 2003, p. 24, http://maic.jmu.edu/journals/masg/MASG%20NewsLetter%20October2003.doc (November 13, 2003).

389 Human Rights Watch interview with CMOC officer.

390 Human Rights Watch interview with Lieutenant Colonel Tim Everhard, commanding officer, Third Ordnance Battalion, U.S. Army, Baghdad, May 14, 2003.

391 Human Rights Watch interview with John Thompson, CMOC representative, First U.K. Armoured Division, Basra, May 28, 2003.

392 Human Rights Watch interview with Lieutenant Colonel John Shanahan.

393 Human Rights Watch interview with Lieutenant Colonel Tim Everhard.

394 Human Rights Watch interview with international aid worker #2.

395 Human Rights Watch interview with Major Michael Samarov.

396 “Euphrates Battle May Be Biggest So Far,” CNN.com, March 25, 2003, http://www.cnn.com/2003/WORLD/meast/03/25/sprj.irq.war.main/ (retrieved October 20, 2003).

397 Human Rights Watch, “Iraqi Mines Found in Mosque,” Press Release, April 2, 2003.

398 Human Rights Watch interview with CMOC officer (reporting on Baghdad); Human Rights Watch interview with Major Michael Samarov (reporting on Karbala’).

399 Human Rights Watch interview with Lieutenant Colonel John Shanahan.

400 Human Rights Watch interview with Major Michael Samarov.

401 Human Rights Watch interview with Danish Church Aid, Basra, May 28, 2003.

402 Human Rights Watch interview with Ugo Bernieri, Relief Coordinator for the Italian Red Cross, Baghdad, May 14, 2003.

403 Human Rights Watch interview with Bill Van Ree, May 29, 2003.

404 Human Rights Watch interview with `Abdul-Amir Matrud Lafta, al-Nasiriyya, May 7, 2003. Lafta, 47, was the victim’s father.

405 Christine Spolar, “FBI Can’t Detect Common Signature in Five Major Iraqi Bomb Attacks,” Chicago Tribune, September 17, 2003.

406 Ibid. Iraqi officials also said that the munitions “could easily have been stolen from unguarded weapons depots.” “Although U.S. military officials maintain that all known munitions sites have ‘some level of protection,’ Iraqi law-enforcement officials have found dozens of sites—including a vast facility about 35 miles [56 kilometers] outside Baghdad and another one 16 miles [26 kilometers] outside Najaf—so poorly guarded that scavengers are regularly seen rummaging through the weaponry. At the Najaf weapons site, at least one scavenger told a reporter that he could enter the grounds by bribing Iraqi guards the equivalent of $3. In Baghdad, law-enforcement officials who recently visited the site found no guards or barriers in place and hundreds of warheads exposed, many with their nose cones removed and their explosives in clear sight.” Ibid.

407 Harry de Quetteville and Sally Pook, “Frightened Aid Workers Set to Flee Iraq: ‘We Are Used to Working in Theatres of War, but This Is Something Else,’” Daily Telegraph, September 1, 2003. See also Beatriz Lecumberri, “As U.N. Pulls Out of Iraq, NGOs Lose Heart,” Agence France-Presse, September 26, 2003.

408 “U.N. Pledges to Continue Working in Iraq,” Agence France-Presse, October 1, 2003. “The staff of the United Nations and particularly the staff of the UNHCR, if they do not return to the country, this will have very deleterious consequences on a humanitarian level,” Iraqi’s interim Minister for Migration and Exiled Persons Mohammed Jassem Khudir told the U.N. high commissioner for refugees. Ibid.

409 The pullout was a response to a car bombing that killed twelve people at the ICRC headquarters in Baghdad. “UN Says International Staff Are All out of Baghdad,” U.N. News Service, November 6, 2003. In early November, the United Nations still had about forty international staff members in northern Iraq and 4,000 Iraqi staff members around the country. Ibid. See also Marc Carnegie, “Annan Vows Change as UN Moves Ahead with Iraq Pullout,” Agence France-Presse, November 3, 2003.

410 Sally Sara, “Red Cross Cuts Iraq Operation,” Australian Broadcasting Corporation, November 9, 2003.

411 Iraq Coalition Casualty Count, n.d., http://lunaville.org/warcasualties/Summary.aspx (retrieved November 11, 2003). As of November 11, 2003, this site listed a total of 281 Coalition military deaths after May 1, including 171 hostile and 110 non-hostile. From March 20 to May 1, it reported 172 deaths, including 142 hostile and 30 non-hostile.

412 Human Rights Watch interview with Gunnery Sergeant Tracey Jones.

413 Briefing by Lieutenant Colonel Alan Butterfield, British Army, CMOC, Basra, May 3, 2003.

414 Human Rights Watch, “Iraq: Basra: Unprotected Munitions Injure Civilians,” Press Release, May 6, 2003.

415 Ibid.

416 Human Rights Watch interview with Lieutenant Colonel John Shanahan.

417 Human Rights Watch interview with Bill Van Ree, team leader, UNMACT, Basra, May 28, 2003.

418 Human Rights Watch interview with Bill Van Ree, May 29, 2003.

419 Human Rights Watch interview with senior CENTCOM official #2.

420 Protocol I, art. 58.

421 Ibid., art. 53.

422 Fourth Geneva Convention, art. 19.

423 Protocol I, art. 12.

424 Hague Regulations, art. 43.

425 CCW, Draft Explosive Remnants of War Protocol, September 2003, art. 1(3).

426 Ibid., Technical Annex.

427 Ibid., art. 5.

<<previous | index | next>> | December 2003 |