<<previous | index | next>>

II. CONDUCT OF THE AIR WAR

Significant civilian casualties occurred in the air war in Iraq despite the use of a high percentage of precision weapons. Of the 29,199 bombs dropped during the war by the United States and United Kingdom, nearly two-thirds (19,040) were precision-guided munitions.21 In the Persian Gulf conflict in 1991, 8 percent of all bombs dropped were PGMs; in Yugoslavia in 1999 approximately one-third were PGMs; in Afghanistan in 2002 approximately 65 percent were PGMs.22

Many of the civilian casualties from the air war occurred during U.S. attacks targeting senior Iraqi leaders. The United States used an unsound targeting methodology that relied on intercepts of satellite phones and inadequate corroborating intelligence. Targeting based on geo-coordinates derived from satellite phones in essence rendered U.S. precision weapons potentially indiscriminate. This flawed targeting strategy was compounded by the lack of an effective assessment both prior to the attacks of the risks to civilians (what the U.S. military calls a “collateral damage estimate” or CDE) and following the attacks of their success and utility (what the U.S. military calls a “battle damage assessment” or BDA).

The use of air-delivered cluster bombs against targets in or near populated areas also contributed to the civilian death toll, although to a lesser degree. As detailed in the ground war chapter of this report, ground-delivered cluster munitions were a major cause of civilian casualties, while air-delivered cluster weapons caused a relatively small number of civilian casualties.

Beyond serious technical or human failures resulting in missed targets, largely avoided in Iraq were the types of attacks that led to significant civilian casualties and civilian suffering in previous U.S. air wars: extensive use of cluster bombs in or near populated areas; destruction of electrical and other dual-use facilities; widespread daylight attacks; and inappropriate targeting choices, particularly with respect to mobile targets.

Coalition forces took significant steps to protect civilians during the air war, including increased use of precision-guided munitions when attacking targets situated in populated areas and generally careful target selection. The United States and United Kingdom recognized that employment of precision-guided munitions alone was not enough to provide civilians with adequate protection. They employed other methods to help minimize civilian casualties, such as bombing at night when civilians were less likely to be on the streets, using penetrator munitions and delayed fuzes to ensure that most blast and fragmentation damage was kept within the impact area, and using attack angles that took into account the locations of civilian facilities such as schools and hospitals.23

But there were still failures in the conduct of the air war that led to the loss of civilian life or to other civilian harm. The most egregious was the flawed targeting of Iraqi leadership. While to a lesser extent than in other recent conflicts, U.S. and U.K. air forces also used some cluster bombs in or near populated areas. Attacks on certain civilian power facilities caused additional civilian suffering, and the legality of attacks on media installations was questionable.

This section contains a synopsis of the air war, an examination of attacks on Iraqi leadership and other emerging targets (including problems related to collateral damage estimates and battle damage assessment), and an analysis of attacks on fixed strategic targets (including electrical power, telecommunications, media, and government and military facilities). Finally, it looks at the problematic use of air-delivered cluster bombs by the United States and the United Kingdom.

Synopsis of the Air War

The war in Iraq started at 3:15 a.m. on March 20, 2003, with an attempt to “decapitate” the Iraqi leadership by killing Saddam Hussein.24 This unsuccessful air strike was not part of long-term planning but was instead a “target of opportunity” based on late-breaking intelligence, which ultimately proved incorrect.25

The major air war effort began at approximately 6:00 p.m. on the same day with an aerial bombardment of Baghdad and the Iraqi integrated air defense system. During the early morning hours of March 21, Coalition air forces attacked targets in Basra, Mosul, al-Hilla, and elsewhere in Iraq. On the night of March 21, precision-guided munitions began destroying government facilities in the Iraqi capital. The air war shifted to attacks on Republican Guard divisions south of Baghdad after the sandstorms of March 25 stalled the ground offensive, but the bombardment of Baghdad continued. U.S. forces hit telecommunications facilities on the night of March 27.

Daylight bombing in Baghdad began on March 31, and elements of the Republican Guard around the city bore the brunt of the aerial assault aimed at paving the way for U.S. ground forces. The bombing of government facilities largely ceased by the morning of April 3 when the airport was taken, but attacks on Republican Guard units continued. On April 5, close air support missions flew over Baghdad to support ground combat. The same day, the United States bombed the reported safe house of `Ali Hassan al-Majid (known as “Chemical Ali”) in Basra. On April 7, air attacks targeted Saddam Hussein and other Iraqi leaders in Baghdad. On April 9, Baghdad fell.

Collateral Damage Estimates

The U.S. military uses the term “collateral damage” when referring to harm to civilians and civilian structures from an attack on a military target. Collateral damage estimates are part of the U.S. military’s official targeting process and are usually prepared for targets well in advance.26 Since the CDE influences target selection, weapon selection, and even time and angle of attack, it is the military’s best means of minimizing civilian casualties and other losses in air strikes.

Collateral damage assessments are a key way for the military to fulfill its obligations under international humanitarian law. International humanitarian law requires an attack to be cancelled or suspended if it is expected to cause loss of civilian life or property that “would be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated.”27 Assessment of collateral damage is necessary to perform this proportionality test adequately.

U.S. air forces carry out a collateral damage estimate using a computer model designed to determine the weapon, fuze, attack angle, and time of day that will ensure maximum effect on a target with minimum civilian casualties.28 Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld reportedly had to authorize personally all targets that had a collateral damage estimate of more than thirty civilian casualties.29

Asked how carefully the U.S. Air Force reviewed strikes in Iraq for collateral damage, a senior U.S. Central Command official responded, “with excruciating pain.” He told Human Rights Watch,

[T]he primary concern for the conduct of the war was to do it with absolutely minimum civilian casualties. . . . The first concern is having the desired effect on a target. . . . Next is to use the minimum weapon to achieve that effect. In the process, collateral damage may become one of the considerations that would affect what weapon we had to choose. . . . All of the preplanned targets had a CDE done very early in the process, many months before the war was actually fought. . . . For emerging target strikes, we still do a CDE, but do it very quickly. The computer software was able to rapidly model collateral effects.30

Strikes with high collateral damage estimates received extra review. According to another senior CENTCOM official,

CENTCOM came up with a list of twenty-four to twenty-eight high CDE targets that we were concerned about. . . . They had a direct relationship to command and control of Iraqi military forces. These [high CDE targets] were briefed all the way to Bush. He understood the targets, what their use was, and that even under optimum circumstances, there would still be as many as X number of civilian casualties. This was the high CD target list. There were originally over 11,000 aim points when we started the high collateral targeting. Many were thrown out, many were mitigated. We hit twenty of these high collateral damage targets.31

Strikes against emerging targets also received review although the process was done much more quickly. U.S. Army Major General Stanley McChrystal, vice director for operations on the Joint Chiefs of Staff, explained the situation in this way:

There tends to be a careful process where there is plenty of time to review that [the targets]. . . . [T]hen we put together certain processes like time-sensitive targeting. And those are when you talk about the crush of an emerging target that might come up, that doesn’t have time to go through a complicated vetting process. . . . [T]here still is a legal review, but it is all at a much accelerated process because there are some fleeting targets that require a very time-sensitive engagement, but they all fit into pre-thought out criteria.32

For the most part, the collateral damage assessment process for the air war in Iraq worked well, especially with respect to preplanned targets. Human Rights Watch’s month-long investigation in Iraq found that, in most cases, aerial bombardment resulted in minimal adverse effects to the civilian population.

The major exception was emerging targets, especially leadership targets. A Department of Defense source told Human Rights Watch that CENTCOM did not perform adequate collateral damage estimates for all of the leadership strikes due to perceived time constraints.33 While the U.S. military hailed the quick turn-around time between the acquisition of intelligence and the air strikes on leadership targets, it appears the haste contributed to excessive civilian casualties because it prevented adequate collateral damage estimates.

Emerging Targets—Iraqi Leadership

Emerging targets develop as a war progresses instead of being planned prior to the initiation of hostilities. They include time-sensitive targets (TSTs) that are fleeting in nature (such as leadership), enemy forces in the field, mobile targets, and other targets of opportunity.

It appears that U.S. air forces learned some lessons from the problems encountered with emerging targets in recent conflicts. Perhaps most notably, in Yugoslavia, U.S. aircraft bombed many civilian convoys after mistaking them for military targets.34 In Iraq, there was only one reported case of a civilian vehicle being mistakenly targeted by aircraft.35 Human Rights Watch researchers also found no instances of civilian casualties directly related to air strikes against Iraqi forces in the field, except those involving use of cluster bombs.36

A significant new problem related to emerging targets, however, was evident in Iraq. The targeting of Iraqi leadership resulted in dozens of civilian casualties that the United States could have prevented if it had taken additional precautions. This phenomenon has gone largely unremarked upon by U.S. military and civilian officials.

The United States targeted adversary leadership in prior armed conflicts. It did so in a limited way in Yugoslavia when Slobodan Milosevic’s residence was bombed in an attempt to kill him.37 The effort was more widespread in Afghanistan. As part of the attempt to kill Taliban leader Mullah Omar and al-Qaeda head Osama bin Laden, the United States bombed homes associated with the two men. It also attacked convoys and destroyed caves in the pursuit of Taliban and al-Qaeda leadership.38 Afghanistan, however, has few population centers, and most attacks occurred in relatively remote areas. In Iraq, by contrast, U.S. planes bombed densely populated neighborhoods in their attacks on Iraqi leadership.

The aerial strikes on Iraqi leadership constituted one of the most disturbing aspects of the war in Iraq for several reasons. First, many of the civilian casualties from the air war occurred during U.S. attacks on senior Iraqi leadership officials. Second, the intelligence and targeting methodologies used to identify potential leadership targets were inherently flawed and led to preventable civilian deaths. Finally, every single attack on leadership failed. None of the targeted individuals was killed, and in the cases examined by Human Rights Watch, local Iraqis repeatedly stated that they believed the intended targets were not even present at the time of the strike.

Time-Sensitive and High-Value Targets

During the war in Iraq, the U.S. Central Command identified a set of emerging targets as “time sensitive.” Time-sensitive targets were targets that were fleeting in nature.39 According to a senior official, CENTCOM designated leadership targets, a subset of time-sensitive targets, as high-value targets due to their perceived intrinsic value to the successful conclusion of major combat operations.40

The high-value targets included the top fifty-five Iraqis on the “Black List” of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). This became CENTCOM’s “most wanted” list.41 In total, the United States launched fifty attacks against Iraqi leaders in rapidly planned and executed air strikes. By mid-November 2003, forty of the fifty-five had been captured or killed or had surrendered—all after the declared end of major combat operations. The remaining fifteen, including Saddam Hussein, are considered “at large” by CENTCOM.42

Of the fifty aerial strikes against Iraqi leaders, not one resulted in the death of the intended target. Yet in four strikes researched by Human Rights Watch, forty-two civilians were killed and dozens more were injured. Human Rights Watch investigated other air strikes resulting in civilian casualties that appear to have been attacks targeting leadership, but it has been unable to confirm the identity of the intended target.43

The dismal record in targeting leadership is not unique to the war in Iraq. Apparently, in both Yugoslavia and Afghanistan, not one of the intended leadership targets was killed in an air strike.44 In fact, the United States in the past has admitted it did not even know at whom it was shooting. Following a November 2001 attack on a suspected leadership target in Afghanistan, Pentagon spokesperson Victoria Clarke stated, “This was a good target. They had a confluence of intelligence which led us to believe there was senior leadership in the building. We don’t have names. We don’t have a sense of exactly who was in there.”45 It is difficult to understand how the military could assess a “good target” if it admits not knowing who the target was.

In an August 2003 report, the U.S. Air Force criticized its use of time-sensitive targeting in Afghanistan. Although it had targeted leadership in previous conflicts, the United States introduced the TST process in Afghanistan as it fused highly accurate weapons with the ability to target in near-real time. The report found that a “single authoritative TST process doctrine does not exist” and that “[t]here is no mechanism to measure performance of TST processes.”46 It called on the Air Force to: (1) “develop meaningful metrics to assess the performance of the TST processes, and develop procedures to measure TST process performance during combat operations,” and (2) “study the relationship between TST doctrine and TST technology to determine the extent to which technology drives TST doctrine.47 These criticisms and recommendations apply equally well to time-sensitive targeting in Iraq. The Air Force acknowledged that technology should not be the driving factor behind air strikes; just because a capability exists does not mean it should be used. It also recognized that the targeting process required an ability to measure effectiveness. In Iraq, the fascination with the ability to track targets via satellite phone and the inadequacies of the battle damage assessment process contributed to the failure of leadership targeting.

Flawed Targeting Methodology

In attacking leadership targets in Iraq, the United States used an unsound targeting methodology largely reliant on imprecise coordinates obtained from satellite phones. Leadership targeting was consistently based on unreliable intelligence. It is also likely that Iraqi leaders engaged in successful deception techniques. This combination of factors led directly to dozens of civilian casualties.

The United States identified and targeted some Iraqi leaders based on GPS coordinates derived from intercepts of Thuraya satellite phones.48 Thuraya satellite phones are used throughout Iraq and the Middle East. They have an internal GPS chip that enabled American intelligence to track the phones. The phone coordinates were used as the locations for attacks on Iraqi leadership.

Targeting based on satellite phone-derived geo-coordinates turned a precision weapon into a potentially indiscriminate weapon. According to the manufacturer, Thuraya’s GPS system is accurate only within a one-hundred-meter (328-foot) radius.49 Thus the United States could not determine from where a call was originating to a degree of accuracy greater than one-hundred meters radius; a caller could have been anywhere within a 31,400-square-meter area. This begs the question, how did CENTCOM know where to direct the strike if the target area was so large? In essence, imprecise target coordinates were used to program precision-guided munitions.

Furthermore, it is not clear how CENTCOM connected a specific phone to a specific user; phones were being tracked, not individuals. It is plausible that CENTCOM developed a database of voices that could be computer matched to a phone user.

The Iraqis may have employed deception techniques to thwart the Americans. It was well known that the United States used intercepted Thuraya satellite phone calls in their search for members of al-Qaeda.50 CENTCOM was so concerned about the possibility of the Iraqis turning the Thuraya intercept capability against U.S. forces that it ordered its troops to discontinue using Thuraya phones in early April 2003. It announced, “Recent intelligence reporting indicates Thuraya satellite phone services may have been compromised. For this reason, Thuraya phone use has been discontinued on the battlefields of Iraq. The phones now represent a security risk to units and personnel on the battlefield.”51 It is highly likely the Iraqi leaders assumed that the United States was attempting to track them through the Thuraya phones and therefore possible that they were spoofing American intelligence.

The United States undoubtedly attempted to use corroborating sources for satellite phone coordinates. Based on the results, however, accurate corroborating information must have been difficult if not impossible to come by and additional methods of tracking the Iraqi leadership just as unreliable as satellite phones.

Satellite imagery and signals intelligence (communications intercepts) apparently yielded little to no useful information in terms of targeting leadership. Detection of common indicators such as increased vehicular activity at particular locations seems not to have been meaningful. Human sources of information were likely the main means of corroborating the satellite phone information in tracking the Iraqi leadership. A human intelligence source was reportedly used to verify the Thuraya data acquired in the attack on Saddam Hussein in al-Mansur, described below.52 But the source was proven wrong. Human sources were also reportedly used to verify the attack on `Ali Hassan al-Majid in Basra, as well as the strike on al-Dura that opened the war.53 Given the lack of success, it seems human intelligence was completely unreliable.

Without reliable intelligence to identify the location of the Iraqi leadership, it appears the United States fell back upon all it had, namely, inaccurate coordinates based on satellite phones, with no guarantee of the identity of the user. Leadership targets developed by inaccurate data should have never been attacked.

Given the dozens of civilian casualties caused by this profoundly flawed method of warfare, aerial attacks on leadership targets such as those witnessed in Iraq should be abandoned until the intelligence and targeting failures have been corrected. Like all attacks, leadership strikes should not be carried out without an adequate collateral damage estimate; strikes should not be based solely on satellite phone intercepts; and there should be no strikes in densely populated areas unless the intelligence is considered highly reliable. Consideration should also be given to possible alternative methods of attack posing less danger to civilians.54

Ineffective Battle Damage Assessment

The U.S. military’s targeting methodology includes assessing the effectiveness of an attack after it is completed.55 Battle damage assessment is considered necessary to evaluate the success or failure of an attack so that lessons learned can be applied and improvements made to future missions. BDA is carried out during a conflict as well as at the cessation of hostilities. Effective BDA can reduce the danger to civilians in war by allowing corrective actions to be taken.56

Although air strikes on Iraqi leadership repeatedly failed to hit their target and caused many civilian casualties, no decision was made during major combat operations to stop this practice. This was due at least in part to ineffective battle damage assessment. A senior CENTCOM official told Human Rights Watch that the BDA process is “broken.” “The process cannot keep up with the pace of operations on the battlefield. The battlefield is moving and BDA can’t keep up.”57

Major General McChrystal of the Joint Chiefs of Staff stressed the degree to which the United States is concerned about collateral damage and effective battle damage assessment:

[O]ne of the things I would highlight at the beginning, that we have proven already in this operation, as we said we would, every time we have a case where there is a real or even potential case of unintended civilian injury or death or collateral damage to structures, we’ve investigated it. And we go back and we look at the targeting; we account for every munition that, in fact, was suspended; we look for whether the aim points that we intended to hit were hit, to determine if, in fact, there was the result of our targeting unintended civilian damage—or casualties, or damage, and then we correct the errors as we go.58

With respect to the leadership attacks in Iraq it appears that effective BDA was not performed. The battle damage assessments should have led the United States to realize the leadership targeting was ineffective before a full fifty missions were flown. If attacks are repeatedly unsuccessful and result in significant civilian casualties, the entire target set should be reassessed. Leadership targeting should never have been allowed to reach such a high number of failed strikes that led to significant civilian deaths.

Case Studies of Attacks on Leadership Targets

Human Rights Watch’s investigations in Iraq found that attacks on leadership likely resulted in the largest number of civilian deaths from the air war. The following case studies illustrate the impact on civilians of the flawed targeting methodology and intelligence used in leadership attacks.

Al-Dura Farm, Baghdad

The war opened on March 20 with an attempted attack on Saddam Hussein. This strike was the beginning of a pattern that would be repeated many times. The U.S. military targeted a facility in the mistaken belief that the Iraqi leadership was there; instead of “decapitating” the regime, this strike resulted in fifteen civilian casualties because of faulty intelligence.

A human intelligence source provided the CIA with information on Saddam Hussein’s alleged location at a farm in al-Dura, a district of southeastern Baghdad.59 Two F-117A Nighthawk aircraft dropped four EGBU-27 2,000-pound penetrator bombs at 3:15 a.m. on a reported bunker at the farm. Moments later, the rest of the farm was hit with up to forty cruise missiles (Tomahawk Land Attack Missiles, or TLAMs) in an attempt to kill Saddam Hussein.60 The U.S. military later acknowledged there was no bunker at the farm, and Saddam Hussein broadcast a television interview days later.61 The attack resulted in one civilian killed and fourteen wounded, including nine women and a child.62

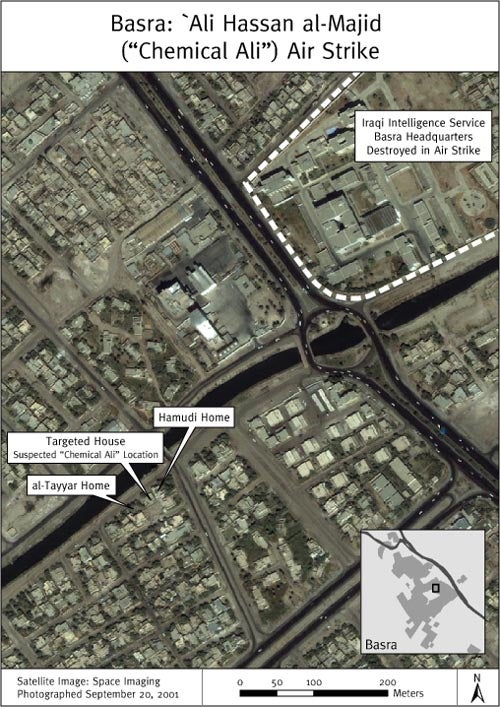

Al-Tuwaisi, Basra

U.S. aircraft bombed a building in al-Tuwaisi, a residential area in downtown Basra at approximately 5:20 a.m. on April 5, 2003, in an attempt to kill Lieutenant General `Ali Hassan al-Majid. Al-Majid, known as “Chemical Ali” because of his role in gassing the Kurds in the 1988 Anfal Campaign,63 was in charge of southern Iraq during the recent war. Initial British reports indicated that al-Majid was killed in the attack. CENTCOM later reversed this claim and changed al-Majid’s status back to “at large.” Coalition forces ultimately captured al-Majid on August 21, 2003.64

Map 08

Download PDF (1.7 Mb)

U.S. weapons hit the targeted building in the densely populated section of Basra, but the buildings surrounding the bomb strike—filled with civilian families—were also destroyed. Human Rights Watch investigators found that seventeen civilians were killed in this attack.65

The homes of the Hamudi and al-Tayyar families sat on either side of the building bombed by American forces. The homeowners gave Human Rights Watch conflicting reports of possible Iraqi government activity in the targeted building. `Abd al-Hussain Yunis al-Tayyar said there were members of the Iraqi Intelligence Service, or Mukhabarat, staying there, while `Abid Hassan Hamudi said it was vacant. Both denied any Iraqi leadership presence, as did all others interviewed. Al-Tayyar, Hamudi, and their families never saw al-Majid in the area.66

In the early morning hours of Saturday, April 5, al-Tayyar, a 50-year-old laborer, went to his garden to get water. Moments later an American bomb slammed into the targeted house next door, destroying his house as well. He picked himself up and immediately began to search the debris. He spent the rest of the day working to pull the dead bodies of his family from the rubble of his home, finally reaching his dead son at 4:00 p.m.67

The dead included:

- As’ad `Abd al-Hussain al-Tayyar, 30, son

- Qarar As’ad al-Tayyar, 12, grandson (son of As’ad)

- Haidar As’ad al-Tayyar, 9, grandson (son of As’ad)

- Saif As’ad al-Tayyar, 6, grandson (son of As’ad)

- Intisar `Abd al-Hussain al-Tayyar, 30, daughter

- Khawla `Ali al-Tayyar, 9, granddaughter (daughter of Intisar)

- Hind `Ali al-Tayyar, 5, granddaughter (daughter of Intisar)

The Hamudi family home stood on the other side of the targeted house. `Abid Hassan Hamudi is a 70-year-old retired oil industry worker. His son, Dr. Akram Hamudi, is renowned in Basra as the senior surgeon at Basra Teaching Hospital. Dr. Hamudi spent the war in the hospital treating injured Iraqis. His family was staying in the Hamudi family home for safety, believing the Americans and British would never bomb civilians. In total, thirteen members of the extended family were living in a makeshift safe room made of reinforced concrete.68

`Abid Hamudi told Human Rights Watch that there were two bombs in the attack. The first bomb missed its target and slammed into the road a few hundred meters away, while the second hit the targeted home, also reducing his home to rubble. Hamudi was able to save three people, his daughter and her two sons, a five-year-old and six-year-old, all of whom were injured in the blast. The other ten people in his house perished.69 “Why did this happen?” Hamudi asked a reporter. “Ten lives are gone. The house was completely destroyed. You came to save us, to protect us. That’s what you said. It’s now the contrary. Innocent people are killed.”70

The dead included:

- Dr. Khairiyya Shakir, 68, wife, gynecologist

- Wisam `Abid Hassan, 38, son, computer engineer

- Dr. Ihab `Abid Hassan, 34, son, gynecologist

- Nura, 6 months, granddaughter (daughter of Dr. Ihab)

- Zainab Akram, 19, granddaughter, pharmacist

- Zain al-`Adidin Akram, 16, grandson

- Mustafa Akram, 14, grandson

- Hassan Iyad, 11, grandson

- Zaina Akram, 12, granddaughter

- `Amr Muhammad, 19 months, grandson

The size of the crater suggests that the weapon used in the April 5 attack was a 500-pound laser-guided bomb, the smallest PGM available. A second crater in the street a few hundred meters away, which is consistent with the crater found in the home, supports the assertion that the first bomb missed and was soon followed by another.71

The collateral damage estimate done on the target appears to have allowed for a high level of civilian damage. This attack may have been approved due to the perceived military value of al-Majid. Had smaller weapons been used, however, many civilian lives may have been spared. A senior CENTCOM official told Human Rights Watch that the U.S. military needs smaller munitions with lower yields that will reduce collateral damage.72

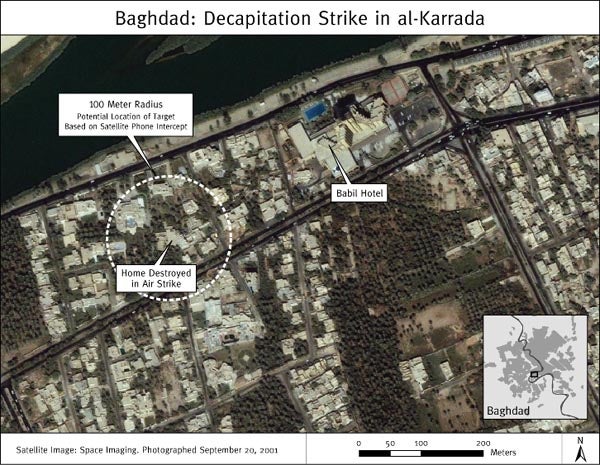

Al-Karrada, Baghdad

On April 8, Sa`dun Hassan Salih lifted his nephew’s two-month-old daughter, Dina, from the grass in front of the smoking hole that had been her home. She was alive, both arms and legs broken, but she was orphaned. Her family had been staying in Salih’s home in the affluent al-Karrada neighborhood of Baghdad, secure in the belief that such a densely populated area of the city would not be targeted. But they would often return to their home, one mile (1.6 kilometers) away, to get some clothes or other things they needed. “That night they went home to get some belongings,” said Salih. “We all felt safer together as a family. If we were going to die, we would die together. But no one would bomb a home. My nephew was the last to leave the house, around 9:00 p.m., in his car. That is the last time I ever saw him.”73

Minutes later, two bombs, seconds apart, destroyed Zaid Ratha Jabir’s home and those inside. Incredibly, Dina survived. She was blown out of the home by the blast and now lives with Salih and his wife, `Imad Hassun Salih. At first they were filled with grief, but now they are angry. “The Americans said no civilians were targeted,” said `Imad. “I don’t understand how this could happen.”74

Map 11

Download PDF (2 Mb)

According to Salih, there were no obvious military targets in the area. He speculated that a bitter family rival lied to the Americans. He said, “Perhaps someone wanted to kill them because of jealousy and told them [the Americans] Saddam or one of his men were there. But my family had no dealings with the regime. We hate Saddam.”75 A Department of Defense official told Human Rights Watch that Saddam Hussein’s half-brother Watban was the intended target of this air strike, and that he was identified through poor communications security.76 This was likely a Thuraya intercept. Watban was eventually captured near the Syrian-Iraqi border near the end of the war almost a week later.

“It was a mistake. I don’t know why the house was hit. There was no intelligence, no army nearby, no weapons. Why did Americans tell the world they hit only places of the army? Why did they hit civilian homes?” asked a distraught Salih.77

The dead included:

- Zaid Ratha Jabir, 36, engineer

- Rana, 25, his wife

- Mina, 2, his daughter

- Mulkiyya, 87, his aunt

- Zahida, 34, Zaid’s sister

- `Adhra, 32, Zaid’s sister

The attack also destroyed the house next door, which belonged to the brother of Sa`ad `Abd al-Rasul `Ali. `Ali said he and his family had left Iraq during the war so no one from this house was injured. He had heard rumors that Saddam Hussein had been in the neighborhood around the time of the strike but described them as “only propaganda.”78

U.S. bombs destroyed this home in al-Karrada during an attempted leadership strike on Saddam Hussein’s half-brother Watban. Of the seven family members inside, only four-month-old Dina Jabir survived. The explosion threw her out of the house and she was found the next day in a neighbor’s garden. © 2003 Bonnie Docherty / Human Rights Watch

Four-month-old Dina Jabir is held by her uncle Sa`dun Hassan Salih. Dina’s family died during an air strike in al-Karrada neighborhood of Baghdad intended for Saddam Hussein’s half-brother Watban, who was captured a week later. Dina was blown out of the home by a U.S. precision bomb and found in a field the next morning suffering from broken bones and orphaned, but alive. © 2003 Marc Garlasco / Human Rights Watch

Map 13

Download PDF ( Kb)

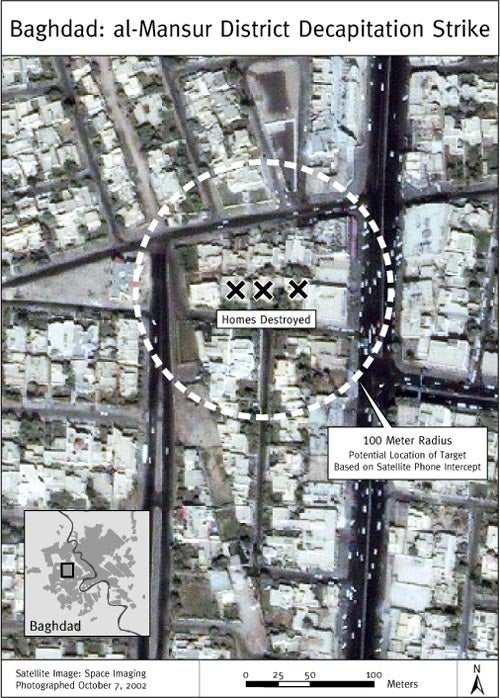

Al-Mansur, Baghdad

On April 7, a U.S. Air Force B-1B Lancer aircraft dropped four 2,000-pound satellite-guided Joint Direct Attack Munitions (JDAMs) on a house in al-Mansur district of Baghdad.79 The attack killed an estimated eighteen civilians.

U.S. intelligence indicated that Saddam Hussein and perhaps one or both of his sons were meeting in al-Mansur.80 The information was reportedly based on a communications intercept of a Thuraya satellite phone. Forty-five minutes later the area was rubble.81

This was the most publicized of the leadership strikes. The U.S. military lauded the short turn-around time “from sensor to shooter,” the time it takes from development of information to when the strike is executed. “From start to finish, it took 45 minutes from the word that Saddam Hussein and other leaders may have entered the building until the bombs hit the structure,” said Major General McChrystal.82

A Department of Defense official told Human Rights Watch, however, that an inadequate collateral damage estimate was done due to the time constraints.83 Forty-five minutes, including the approximately twelve minutes it took the B-1B to fly the mission, was little time to take the raw data of the time and location of the meeting, interpret it, prepare and target the mission, and pass it up the chain in CENTCOM for the decision to make the strike.84

The effects of the strike were stark, a huge crater surrounded by damaged homes. Interviews with residents of the area and press reports indicated approximately eighteen civilians died in the strike. Ahmad al-Sibi, whose house was behind the bomb crater, stated that his home became “like a wave of water” when the bombs struck. He saw three houses fall. He said there was no evidence that Saddam Hussein or any members of the Iraqi government had been there.85

Pentagon officials admitted that they did not know precisely who was at the targeted location. “What we have for battle damage assessment right now is essentially a hole in the ground, a site of destruction where we wanted it to be, where we believe high-value targets were. We do not have a hard and fast assessment of what individual or individuals were on site,” said Major General McChrystal.86

One intelligence official was quoted as saying that since the U.S. military was unsure if Saddam was killed in the strike on al-Dura farm, “just in case he didn’t die before, let’s have him die again.”87 In May, Vice President Dick Cheney said about the strike, “I think we did get Saddam Hussein. He was seen being dug out of the rubble and wasn’t able to breathe.”88 The U.S. government, however, has subsequently said it appears that Saddam Hussein was not killed in the strike; multiple radio announcements attributed to him since the bombing have been judged as probably authentic.89

This strike shows that targeting based on satellite phones is seriously flawed. Even if the targeted individual is actually determined to be on the phone, the person could be far from the impact point. The GBU-31s dropped on al-Mansur have a published accuracy of thirteen meters (forty-three feet) circular error probable (CEP), while the phone coordinates are accurate only to a one-hundred-meter (328-foot) radius.90 The weapon was inherently more accurate than the information used to determine its target, which led to substantial civilian casualties with no military advantages. U.S. military leaders defended these attacks even after revelations that the strikes resulted in civilian deaths instead of the deaths of the intended targets. One said that the strikes “demonstrated U.S. resolve and capabilities.”91

This crater in al-Mansur district of Baghdad is all that remains of three homes destroyed in a U.S. air strike targeting Saddam Hussein on April 7, 2003. Eighteen civilians were killed in the strike. © 2003 Marc Garlasco / Human Rights Watch

Conclusion and Recommendations

Under international humanitarian law, the targeting of military leadership is permissible, even if it results in civilian casualties, so long as the anticipated concrete and direct military advantage outweighs the civilian cost. Aerial strikes targeting the leadership of a party to the conflict (“decapitation strikes” in U.S. military parlance) are governed by the same rules of IHL that apply to other military actions: the individual attacked must be a military target92 and the attack must not be indiscriminate, i.e., it must distinguish between civilians and combatants, and it must not cause harm to the civilian population or civilian objects which could be “excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated” from the attack.93 Human Rights Watch did not assess the military advantage of eliminating specific Iraqi military leaders, but the United States is required to carry out this balancing act prior to launching decapitation strikes.

If they respect these criteria, attacks on enemy leaders who take a direct part in hostilities are not prohibited and are different from assassinations committed outside the context of an armed conflict, which are extrajudicial executions prohibited by international human rights law.94 Aerial strikes on leadership targets, however, still require a particularly high level of scrutiny.

The U.S. practice of decapitation strikes gives rise to a number of concerns. In some cases, the location of the intended target and the imprecision of the coordinates used to direct the attack may have resulted in indiscriminate attacks. More generally, the continued resort to decapitation strikes despite their complete lack of success and the significant civilian losses they caused can be seen as a failure to take “all feasible precautions” in choice of means and methods of warfare in order to minimize civilian losses as required by international humanitarian law.95

The U.S. armed forces should perform a thorough investigation of the battle damage assessment process, determine how it can be improved to mitigate civilian casualties, and implement appropriate changes.

Human Rights Watch recommends that if the United States bombs populated areas, it should:

Complete a collateral damage estimate in advance and balance this against the expected direct and concrete military advantage of the attack. Use the smallest effective precision munitions to limit civilian harm. Carry out a bomb damage assessment as soon as possible after the attack and apply immediate lessons learned.

The United States has committed itself to all these steps, but it needs to implement them more consistently.

Human Rights Watch also recommends that the United States abandon aerial attacks on leadership targets until the targeting and intelligence failures have been corrected. In particular,

Strikes should not be based solely on satellite phone intercepts. There should be no strikes in densely populated areas unless the intelligence is considered highly reliable.

21 Lieutenant General T. Michael Moseley, U.S. Air Force, “Operation Iraqi Freedom—By The Numbers,” April 30, 2003, p. 11 [hereinafter “Operation Iraqi Freedom—By The Numbers”]. This report cites a total of 19,948 guided weapons, including guided cluster bombs, but guided cluster bombs cannot be considered precision weapons because of their large dispersal area. In terms of raw numbers, 1,263 more PGMs were dropped in the first Gulf War than in the 2003 Iraq war. General Accounting Office, “Operation Desert Storm: Evaluation of the Air Campaign,” GAO/NSIAD-97-134, June 1997, appendix 4, table IV.4 (Unit Cost and Expenditure of Selected Guided and Unguided Munitions in Desert Storm).

22 Herman L. Gilster, “Desert Storm: War, Time, and Substitution Revisited,” Airpower, Spring 1996, p. 8; Michael Kelly, “The American Way of War,” Atlantic Monthly,June 2002, p. 16; Gerry Gilmore, “Crusader Not ‘Truly Transformational,’ Rumsfeld Says,” American Forces Press Services, May 16, 2002.

23 See Human Rights Watch telephone interview with senior CENTCOM official #1, Tampa, September 27, 2003.

24 A useful timeline of the war was published in The Guardian and is available at www.guardian.co.uk. All dates and times in this section are local Iraq times.

25 Technical Sergeant Mark Kinkade, “The First Shot,” Airman, July 23, 2003, http://www.af.mil/news/airman/0703/air.html (retrieved November 13, 2003).

26 “Targeting and Collateral Damage,” U.S. CENTCOM Briefing, March 5, 2003.

27 Protocol I, art. 57(2)(b).

28 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with senior CENTCOM official #1.

29 Bradley Graham, “U.S. Moved Early for Air Supremacy,” Washington Post, July 20, 2003, p. A26.

30 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with senior CENTCOM official #1.

31 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with senior CENTCOM official #2, Tampa, September 27, 2003.

32 Major General Stanley McChrystal, “Coalition Targeting Procedures,” Foreign Press Center Briefing, April 3, 2003.

33 Human Rights Watch interview with Department of Defense official, Washington, D.C., August 2003.

34 See, for example, Human Rights Watch, “Civilian Deaths in the NATO Air Campaign,” A Human Rights Watch Report, vol. 12, no. 1 (D), February 2000. This report identifies seven attacks on civilian convoys. There were other problematic attacks on emerging targets in Yugoslavia and Afghanistan. See “Afghanistan Civilian Deaths Mount,” BBC News Online, January 3, 2002, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/south_asia/1740538.stm (retrieved October 21, 2003).

35 On March 24, 2003, a U.S. warplane attacking a bridge about one hundred miles (160 kilometers) from the border with Syria accidentally bombed a bus crossing the bridge, according to Major General McChrystal. Syria claimed five civilians were killed and ten injured. “Civilians Killed in Northern Air Assault,” Australian Broadcasting Corporation News Online, March 25, 2003, http://www.abc.net.au/news/newsitems/s815316.htm (retrieved October 20, 2003); “Syria Says Bus Carrying Civilians Bombed by Coalition Plane,” PBS Online NewsHour, March 24, 2003, http://www.pbs.org/newshour/updates/syria_03-24-03.html (retrieved October 20, 2003).

36 Destroyed Iraqi military vehicles litter the Iraqi countryside. Many were destroyed by air strikes before U.S. ground forces were anywhere near them. During an interview, Colonel David Perkins, commanding officer of the Second Brigade, Third Infantry Division, stated that precision-guided bombs hit many Iraqi vehicles long before his forces encountered them. Later, when scout units found Iraqi forces, U.S. ground forces would often call in air strikes instead of engaging with them with direct fire. Human Rights Watch interview with Colonel David Perkins, commanding officer, Second Brigade, Third Infantry Division, U.S. Army, Baghdad, May 23, 2003.

37 Bradley Graham, “Missiles Hit State TV, Residence of Milosevic,” Washington Post, April 23, 1999.

38 “U.S. Official Says Bin Laden Running Out of Options,” Los Angeles Times, December 11, 2001.

39 “Operation Iraqi Freedom—By The Numbers,” p. 9. This document identifies three types of TSTs: leadership, weapons of mass destruction, and terrorists. It states there were 102 attacks on weapons of mass destruction, fifty on leadership, and four on terrorists. Ibid.

40 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with senior CENTCOM official #2.

41 Ibid.

42 For the status of the fifty-five most wanted, see U.S. CENTCOM, “Iraqi 55 Most Wanted List,” n.d., http://www.centcom.mil/Operations/Iraqi_Freedom/55mostwanted.htm (retrieved October 20, 2003).

43 For example, an air strike in al-Shatra at 3:15 p.m. on April 4 killed six civilians and injured thirty-eight. Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. Salih Qadum, director, al-Shatra General Hospital, al-Shatra, May 27, 2003. This attack may have targeted `Ali Hassan al-Majid (known as “Chemical Ali”); al-Shatra is on the road to Basra, where the Coalition targeted al-Majid the next day. Four strikes in al-Rashidiyya, a town north of Baghdad, around 10:00 p.m. on April 6, killed forty-three civilians and injured twenty-four. Civilians reported that Saddam Hussein was rumored to be in the area and some said they saw an expensive Mercedes speeding through the streets before the bombs fell. Human Rights Watch interviews with `Ali Hirat `Abid, Hadi `Abid `Ali, `Abdullah Latif Hamid, `Abd al-Rahman `Abd al-Latif Ahmad, and Mahmud `Ali Hamada, al-Rashidiyya, October 16, 2003.

44 This does not include attacks with armed Predator drones. These attacks are different from the others in that Predator allows visual confirmation of the target during strikes.

45 “U.S. Planes Blitz Leaders’ Compound,” South China Morning Post, November 29, 2001.

46 Leonard LaVella, “Operation Enduring Freedom Time Sensitive Targeting Process Study,” Air Combat Command Analysis Division, Directorate of Requirements, August 25, 2003.

47 Ibid.

48 Michael Knights, “U.S.A. Learns Lessons in Time-Critical Targeting,” Jane’s Intelligence Review, July 1, 2003; Carl Cameron, “Intelligence Key to Strike on Leadership Target,” FOX News, April 9, 2003, www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,83611,00.html (retrieved October 21, 2003); “Tip about Hussein Leads to Fierce Baghdad Battle That Kills 1 Marine,” Knight Ridder News Service, April 10, 2003; “Suspected Saddam Hideout Slammed by Fierce Bombing,” Knight Ridder News Service, April 8, 2003; Brian Ross, Rhonda Schwartz, and Jill Rackmill, “Missed Opportunity? U.S. Attack May Have Ended Saddam Surrender Attempt,” ABC News.com, April 21, 2003, http://abcnews.go.com/sections/wnt/World/iraq030421_missed_deal.html (retrieved October 20, 2003).

49 Thuraya Satellite Telecommunications Company, “Extensive Roaming and Superior Connectivity,” n.d., http://www.thuraya.com/products/services_marketing.htm (retrieved October 20, 2003). A user must be outside with an unobstructed view of the sky to receive a Thuraya signal.

50 Jason Burke, “Bin Laden Still Alive, Reveals Spy Satellite,” The Observer, October 6, 2002; “Laden Is Alive and Regularly Meeting Omar: U.S. Report,” Times of India, October 7, 2002; “FBI Tracking Muslims to Trace al-Qaeda Men,” The Pioneer, October 7, 2002.

51 U.S. CENTCOM, Headquarters, “Use of Thuraya Phones Discontinued,” News Release 03-04-43, April 3, 2003.

52 John Donnelly, “War in Iraq/Targeting the Leadership; After Airstrike, U.S. Seeks Clues on Fate of Hussein and Sons,” Boston Globe, April 9, 2003, p. A21.

53 Bradley Graham, “U.S. Moved Early for Air Supremacy.”

54 For example, attacks with armed Predator drones allow visual confirmation of the target during strikes.

55 Major General Stanley McChrystal, “Coalition Targeting Procedures.”

56 An example of the potential effectiveness of BDA is the application of lessons learned in the NATO campaign in Yugoslavia during the war. Civilians were killed on the Djakovica-Decane Road when U.S. aircraft incorrectly identified civilian convoys as military in nature. The U.S. military and NATO learned what they were doing wrong and changed the rules of engagement. See Human Rights Watch, “Civilian Deaths in the NATO Air Campaign,” p. 21.

57 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with senior CENTCOM official #2.

58 Major General Stanley McChrystal, “Coalition Targeting Procedures.”

59 Barton Gellman and Dana Priest, “Surveillance Provided Unforeseen ‘Target of Opportunity,’” Washington Post,March 20, 2003.

60 Robert Burns, “Opening Round of War Targets Saddam; Iraq Fires at Troops,” Associated Press, March 20, 2003.

61 Bradley Graham, “U.S. Moved Early for Air Supremacy.”

62 Marian Wilkinson, “Decapitation Attempt Was Worth a Try, George,” Sydney Morning Herald, March 22, 2003.

63 See Human Rights Watch, Genocide in Iraq: The Anfal Campaign Against the Kurds (New York: Human Rights Watch, 1993).

64 Bill Brink, “Former Iraqi Official Known as ‘Chemical Ali’ Is Captured,” New York Times, August 21, 2003.

65 Human Rights Watch interview with `Abd al-Hussain Yunis al-Tayyar, Basra, April 22, 2003; Human Rights Watch interview with `Abid Hassan Hamudi, Basra, April 22, 2003.

66 Human Rights Watch interview with `Abd al-Hussain Yunis al-Tayyar; Human Rights Watch interview with `Abid Hassan Hamudi.

67 Human Rights Watch interview with `Abd al-Hussain Yunis al-Tayyar.

68 Human Rights Watch interview with `Abid Hassan Hamudi.

69 Ibid.

70 Keith B. Richburg, “In Basra, Growing Resentment, Little Aid; Casualties Stoke Hostility Over British Presence,” Washington Post, April 9, 2003, p. A23.

71 The precision-guided munition may have missed its target due to mechanical, electrical, or human error.

72 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with senior CENTCOM official #2.

73 Human Rights Watch interview with Sa’dun Hassan Salih, Baghdad, May 18, 2003.

74 Human Rights Watch interview with `Imad Hassan Salih, Baghdad, May 18, 2003.

75 Human Rights Watch interview with Sa’dun Hassan Salih.

76 Human Rights Watch interview with Department of Defense official.

77 Human Rights Watch interview with Sa’dun Hassan Salih.

78 Human Rights Watch interview with Sa`ad `Abd al-Rasul `Ali, Baghdad, May 17, 2003.

79 David Blair, “Smart Bombs Aimed at Saddam Killed Families,” Daily Telegraph, April 21, 2003, p. 11.

80 John Donnelly, “War in Iraq/Targeting the Leadership; After Airstrike, U.S. Seeks Clues on Fate of Hussein and Sons.”

81 “Saddam May Be Dead,” Knight Ridder Newspapers, April 8, 2003.

82 John Donnelly, “War in Iraq/Targeting the Leadership; After Airstrike, U.S. Seeks Clues on Fate of Hussein and Sons.”

83 Human Rights Watch interview with Department of Defense official.

84 Mark Thompson and Timothy J. Burger, “How to Attack a Dictator, Part II,” Time, April 21, 2003.

85 Human Rights Watch interview with Ahmad al-Sibi, Baghdad, May 22, 2003.

86 Rowan Scarborough, “Saddam Seen at Site,” Washington Times, April 9, 2003.

87 Mark Thompson and Timothy J. Burger, “How to Attack a Dictator, Part II.”

88 David Rohde, “Bomb Crater Probed in Search for Saddam,” New York Times, June 6, 2003, p. A1.

89 “Bremer Says Saddam Alive, Not Behind Attacks,” Associated Press, July 21, 2003; Guy Taylor, “CIA Says Al Jazeera Audiotape ‘Most Likely’ Saddam,” Washington Times, July 8, 2003; “CIA Reported to Believe Saddam is Alive,” United Press International, June 3, 2003.

90 CEP is “the radius of a circle within which half of a missile’s projectiles are expected to fall.” U.S. Department of Defense, “Dictionary of Military Terms,” June 5, 2003, http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/jel/doddict (retrieved October 21, 2003).

91 Bradley Graham, “U.S. Moved Early for Air Supremacy.”

92 Protocol I, arts. 48, 52(2).

93 Ibid., arts. 51(5)(b), 57(2).

94 Since 1976, successive U.S. presidents, including President George W. Bush, have endorsed an executive order (Executive Order 12333) banning political assassinations. This order followed revelations of earlier U.S. assassinations and assassination attempts of various world leaders. Consonant with the rules outlined above, this order does not prohibit targeting enemy combatants and their commanders in an armed conflict, and it does not prohibit the use of lethal force by law enforcement agents when necessary to avoid imminent death or serious injury. But it rightfully prohibits summary execution in any circumstance and the targeted killing of people (other than combatants in armed conflict) in lieu of invoking available criminal justice remedies. See Executive Order 12333 of December 4, 1981, 3 C.F.R. 200 (1981 comp.).

95 Protocol I, art. 57(2)(a).

<<previous | index | next>> | December 2003 |