Abuses by Government and Separatist Groups in Cameroon’s Anglophone Regions

Since then, at least 20 villages identified by satellite show significant numbers of houses burned to the ground, thousands have fled their homes, many have been killed, and inflammatory rhetoric is on the rise. Birgit Schwarz speaks with researcher Jonathan Pedneault, who recently returned from doing research in Cameroon and co-authored the latest Human Rights Watch report on the central African country. He describes what it will take to prevent the crisis from spiraling out of control and the challenges of conducting research in a climate of mutual distrust and widespread abuse by all sides.

What triggered the present conflict between the Anglophone minority and the government?

When British-administered Southern Cameroons decided in 1961 to join the newly independent Republic of Cameroon, formerly administered by France, it did so under the assumption that they would be integrated as part of a federation and would be able to preserve some level of autonomy. However, in 1972 Cameroonians adopted a unitary state that became increasingly centralized. Demands by the Anglophone minority for more autonomy or for a return to a federal system were met with contempt. When, in the fall of 2016, lawyers and teachers took to the streets to denounce what they perceived as increasing marginalization of the Anglophones in the judiciary and the educational system, government security forces responded with repression and arrests.

Is the Anglophone community being marginalized?

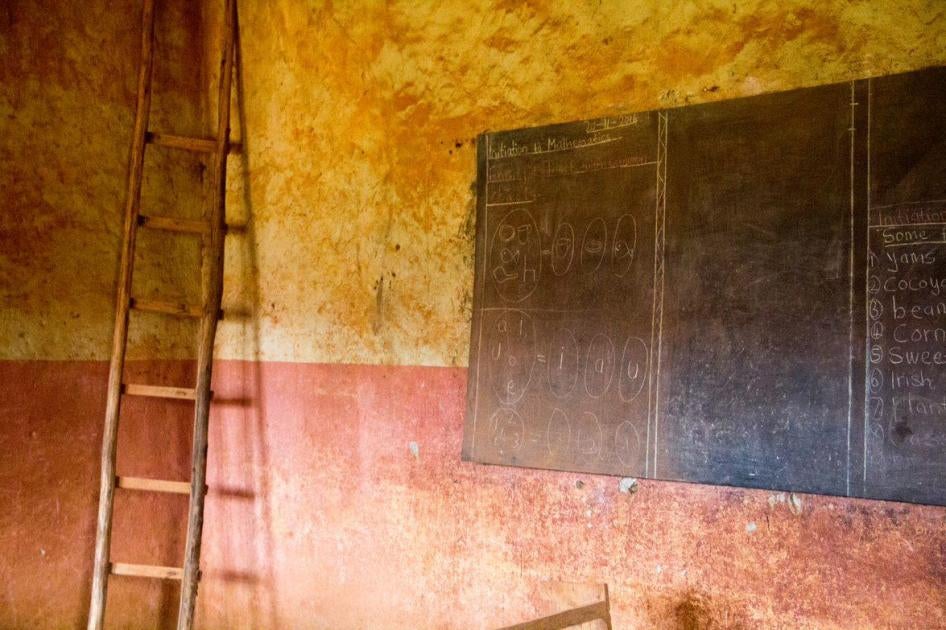

Many within that community certainly feel that they are. The educational system in Cameroon recognizes the existence of an English-speaking system. However, state-employed teachers are hired, nominated, and dispatched by the central government and Anglophones complained those deployed to their areas were mostly francophone or bilingual teachers who do not speak proper English. That angered Anglophone teachers, who felt deprived of job opportunities. The same applies to the legal system. The government has been dispatching attorney generals who are mostly francophone and trained in the civil law system to areas that have traditionally relied on a hybrid between common law and civil law. This angered a lot of the Anglophone lawyers who were educated in common law.

What led to the escalation of the conflict?

In late December 2016 the government entered into negotiations with representatives of the lawyers’ and teachers’ unions. The government claims that many of the demands the unions presented were met, such as to hire more than 1,000 Anglophone teachers and to establish a commission on bilingualism and multiculturalism. The government also said it created additional common law benches at the Supreme Court. But the unions pushed their luck and demanded a referendum on whether to return the county to a federation or to allow the Anglophone regions to separate. The government maintained that it had negotiated in good faith but that the teachers’ and lawyers’ movements were highjacked by extremists from abroad who had only one goal: to destabilize Cameroon and get rid of the president. It responded by outlawing the organizations that represented the teachers and lawyers and by arresting a number of their leaders.

Does the government have a point?

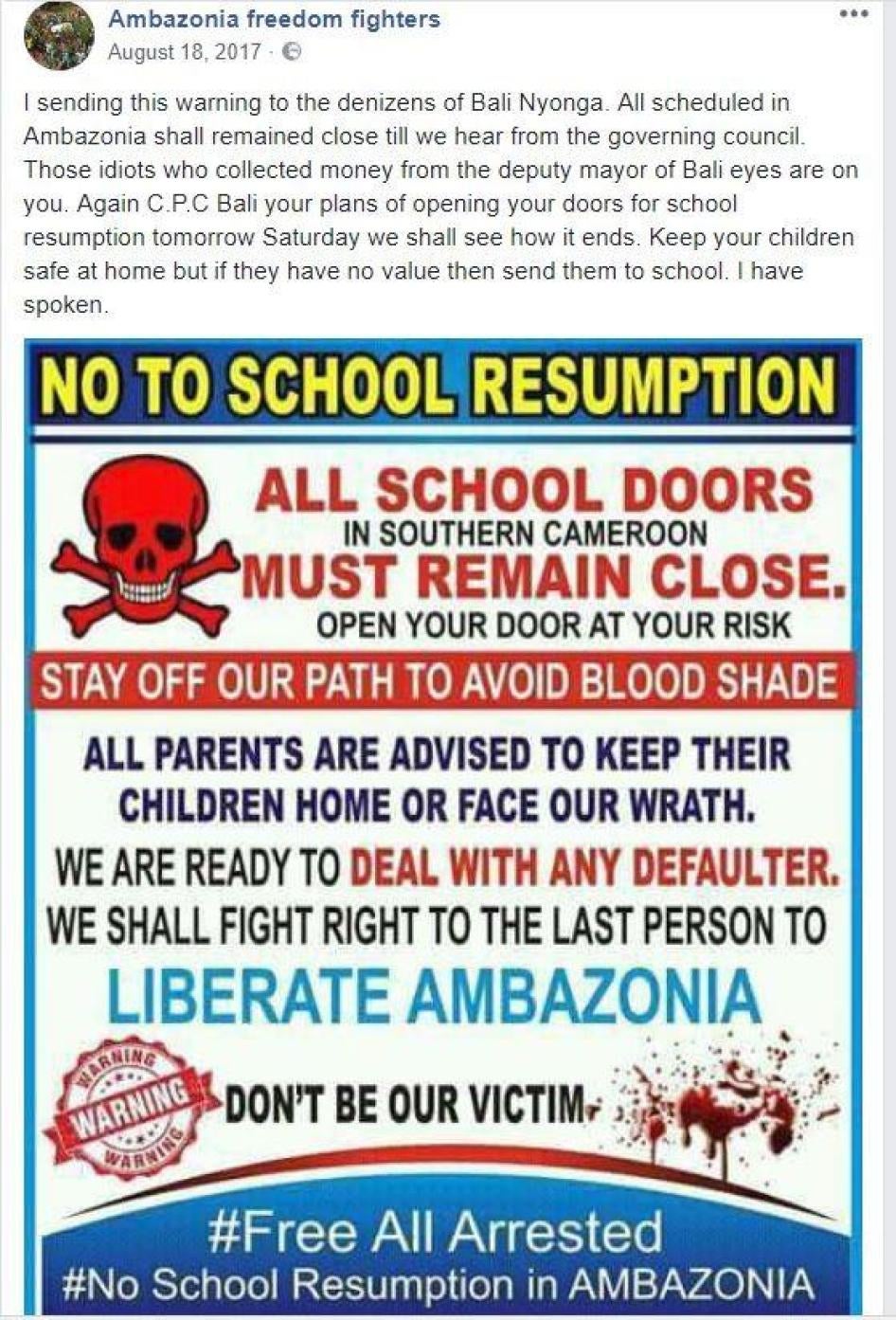

The anglophone diaspora, which is significant both in terms of size and resources, is very politicized and is dominated by a very strong current of opposition to the present government. Separatist activists in the diaspora have been very active in raising funds and making the case that their region deserves independence. When the demonstrations took place in 2016 some began to call for “ghost town” tactics: merchants were asked to keep their shops closed for one day a week to disrupt the economy. These “ghost towns” were enforced violently at times, with threats to burn shops that remained open and to attack shop owners who did not comply. Separatists also began to enforce boycotts of schools by harassing parents and children, threatening principals and teachers, and burning schools. Then, in the summer of 2017, a number of diaspora groups created their own government for the “Republic of Ambazonia,” the entity they claim has sovereignty over the former British-administered Southern Cameroons.

What was the government’s response?

In the fall of 2017, while Cameroon President Paul Biya was in New York for the United Nations General Assembly, massive demonstrations took place in major towns of the North-West and South-West regions. Security forces used live ammunition to disperse the crowds. Houses were raided, their inhabitants roughed up, property destroyed, and some of the more moderate Anglophone leaders were arrested. More recently the government has been using extremely abusive counter-insurgency tactics in areas in which armed separatists are assumed to be operating or where government forces suspect the local civilian population of supporting the insurgents. Villagers told us that troops have been moving into their villages and opening fire, forcing people to flee into the bush. Soon after such raids, they would see smoke rise from the villages, and upon return they would find their homes charred, and older people or people with disabilities, who had not been able to flee, burned to death or executed. These scorched-earth tactics are obviously a violation of human rights law. Yet, neither the government nor senior military personnel appear to have made any serious effort to stop them.

What effect has the conflict had on the two communities?

It has created deep tensions. More and more people in francophone Cameroon are calling for the government to deploy even more aggressive tactics, while the separatist groups, especially in the diaspora, are stoking the fires with inflammatory rhetoric on social media, calling francophones “mad dogs” for instance. Every Monday we are now seeing “ghost towns” enforced by separatists. The cost of food and other commodities is rising. People are less able to export agricultural products to other regions in Cameroon because of the insecurity of the roads. They also struggle to cultivate their land as it has become increasingly difficult to get fertilizer and pesticides. Thousands have been displaced and have either fled to Nigeria or taken refuge with relatives in the cities.

What support do the armed separatists have among the local Anglophone community?

The population is stuck between a rock and a hard place. People feel that these separatist groups are causing mayhem in their communities, attacking local authorities and traditional chiefs, and preventing their children from going to school by threatening teachers or burning schools. Yet at the same time, government forces are attacking their villages, burning their homes, and arresting their children. This heavy-handed response provides the more radical separatist voices with more ammunition to monopolize the discourse. What was a situation that was very much manageable has escalated out of control as a result of both the government forces’ use of abusive tactics and the campaigns by armed separatists, who have been exploiting the population’s anger about government abuses to recruit more fighters, raise more funds, and attract more international attention.

How did you and your colleagues manage to do your research under the circumstances?

We only used larger roads that were safe and stayed in the larger cities in the South-West and North-West that were more stable. There, we were able to meet with internally displaced people who had fled when their villages came under attack. Their testimony provided us with the details and evidence about 12 attacks by security forces on villages. Via satellite imagery, we were able to document burning in 20 villages. But it was difficult research. People were extremely afraid that we could be spies or report them either to the government or to the separatists. We had to use a network of trustworthy go-betweens and met with interviewees in places that provided them with plausible reasons as to why they had been there if ever they should be questioned about who they were meeting with.

What will it take to de-escalate the situation?

The government needs to send clear signals that it is willing to protect the rights of all Cameroonians, including residents of the Anglophone regions. It has recently announced a plan for a humanitarian response for the area. That’s a good sign. But it needs to do much more. It needs to recognize the fact that its soldiers have committed severe abuses. It needs to order a stop to the abuses and ensure accountability for crimes. As for the Anglophone separatist groups, they too need to be willing to put the well-being and safety of the population first, ahead of their political or personal ambitions, or else they are facing the prospect of a protracted war that no one will win and that will only cause more suffering for the people whose interests they claim to defend or protect.

This interview has been edited and condensed.