Rahena, 15, and Suma, 9, perch on low stools reading to one another outside the family home as Ali looks on, cuddling his grandson. The girls are proud of their learning and happy to show it off to visitors. They’ve stayed home to meet us today because Ali believes our visit – as part of a reporting trio to make a video about the curse of child marriage in Bangladesh – is an educational opportunity for them.

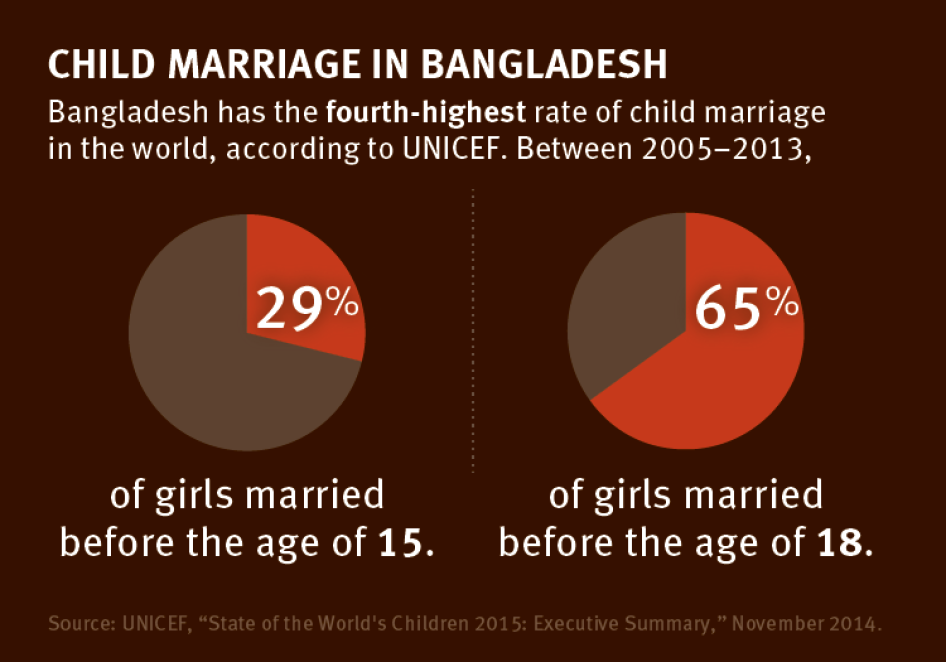

Their older sister, Fatema, didn’t have the same chance: she finished Class 7, at around 12 or 13, but was then married off by her parents because they were poor and didn’t know any better, Ali says. It’s a dark fate for many: Bangladesh leads the world in the rate of girls under 15 years of age who marry – 29 percent, according to a UNICEF study– which means hundreds of thousands of young girls each year find themselves forced into marriage.

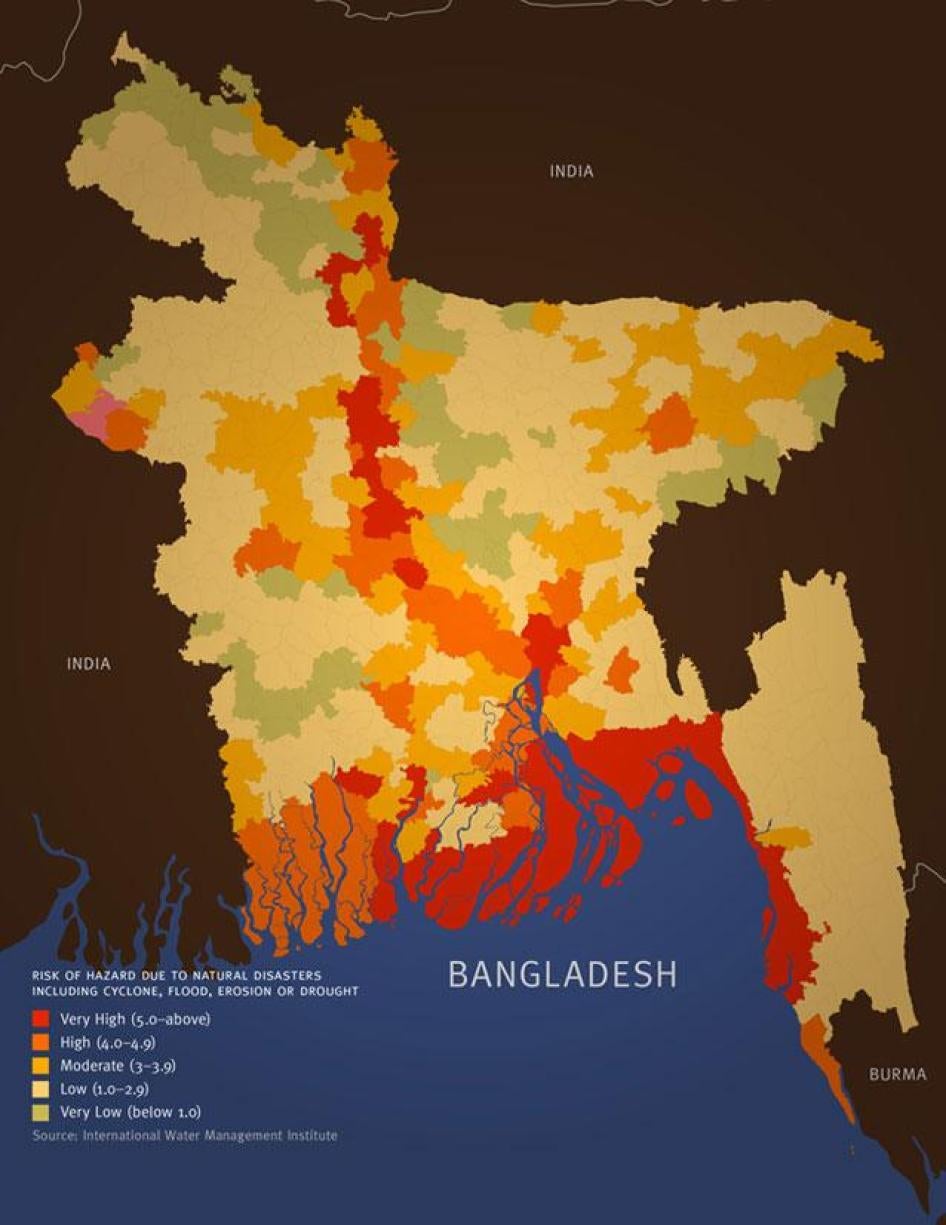

Child marriage in Bangladesh is driven by poverty, often exacerbated by natural disasters. River erosion has washed away land and homes, prompting some parents to marry off their young daughters before losing their livelihoods and others to do so because they feel they can no longer feed their children.

Almost all girls we met who married very young dropped out of school, and they often faced health problems as a result of early pregnancy. They frequently confronted abuse and violence within their new home and have little hope of escaping a life of poverty.

Ali now regrets Fatema’s early marriage – he says he had no idea at the time that it was illegal under Bangladeshi law, which prohibits girls under 18 and boys under 21 from marrying. However, the ban is rarely enforced. Ali has since learnt about the risks to child brides, and has become an activist on the issue.

“I will not marry off my other daughters before the age of 18,” he told us. “If I can provide for my daughter’s education she can get a job and she can live well.”

But it’s life on a knife-edge: “I have to take loans, and when I do, the interest starts to go up,” he said. “It keeps increasing and I never run out of loans. I am always living on credit. But still I would say, no matter how hard I have to work, if Allah wants my children will do well when they continue their education it will be good for us. That is why despite all the hardship I am continuing their education.”

Suma’s schooling costs her parents about 600 or 700 taka per month (about $7 or $8), and she receives a monthly government subsidy of 100 takas. Expenses for Suma and Rahena, who gets no government help these days, include notebooks and pens, exam fees and snacks.

Bangladesh is a development success story by some measures, having significantly increased access to education for girls and boys by providing free primary and secondary schooling. But the government should do more to subsidize books, uniforms and school supplies that can make school unaffordable for the poorest families, and should target assistance toward them. That would improve access to education and remove a key reason for parents to marry off their daughters.

Ali’s three sons all completed school and now hold white-collar jobs. “My parents worked much harder than us, I’m doing a little better with the training that I got. Secondly, my children are a little better off than me… my sons don’t have to drive a rickshaw,” Ali said. And given the social prejudices that can hold girls in Bangladesh back, he added, “I have realized that it is more important for my daughters, than my sons, to get educated.”