Witness: Naziuddin’s Story – How Bangladesh's Officers Killed his Grandson

Naziuddin, a wiry 50-year-old farmer, was living in hiding, changing his location each night after the police perversely charged him with the shooting death of his 12-year-old grandson, Syed. In fact, Naziuddin said, a bullet fired by Bangladesh security forces into a crowd of protesters killed his grandson. The boy had been standing outside his madrassa, a religious school, to watch demonstrators marching through the streets – much like Naziuddin, who looked on from the edge of his field, about 60 meters away. When the protests became chaotic, security forces fired live ammunition into the crowd, killing Syed, Naziuddin said.

Syed’s father was too distraught over his son’s death to talk about it, Naziuddin apologized. But Naziuddin made the daylong journey to Dhaka to speak with Human Rights Watch because he wanted someone to know the truth of what happened, he said. His grandson wasn’t a protester – he was just a curious boy, watching the people on the street.

Bangladesh was rife with protests between February and April. The biggest demonstrations, which involved large swaths of the country, were sparked by a special tribunal’s rulings on crimes committed during the 1971 War of Independence from Pakistan. Many of those sentenced were affiliated with the Jamaat-e-Islami political party. The party denounced the tribunal as biased and organized protests against the rulings.

During this period, security forces killed at least 100 people, almost all unarmed protesters and bystanders, with no one held to account, a new Human Rights Watch report says. The worst day of violence was February 28, the day Naziuddin’s grandson was killed. That afternoon, Delwar Hossain Sayeedi, a charismatic Islamic leader linked to Jamaat, was sentenced to death for murder, torture, and rape committed during the war. Jamaat called for protests, which erupted throughout many areas of Bangladesh.

That morning of the trial began like any other day, with Naziuddin heading to work in the fields near the village and Syed going off to the madrassa.

As soon as the verdict was announced, shopkeepers began to protest in the village. More demonstrators soon joined. Many villagers were followers of Sayeedi, Naziuddin said, as the leader had held an annual religious gathering nearby.

“When we heard the procession we went to watch from a distance,” Naziuddin explained. The crowd of protesters had swelled to the hundreds. Some of the young people started vandalizing shops and beating on shutters with bits of brick. “It was chaos,” Naziuddin said. Emotions ran high.

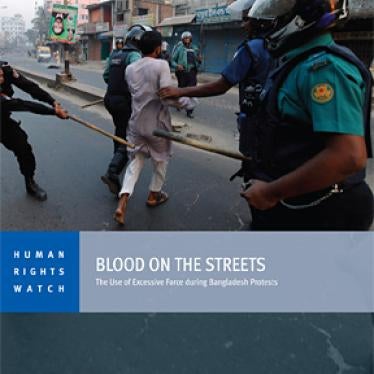

About 60 to 70 officers arrived on the scene, Naziuddin told us. He recognized the police wearing navy blue pants and helmets, and the Border Guards Bangladesh (BGB) by their multi-colored camouflage.

When the procession crossed the street in front of Syed’s madrassa, the protesters spotted the officers and started yelling. “The police attacked with sticks and charged the crowd,” while the BGB stayed back, Naziuddin said. The protesters didn’t have weapons, but they fought back with rocks and bamboo sticks. The confrontation escalated, the crowds surged back and forth. The police began firing rubber bullets and using tear gas, attempting to disperse the crowd.

Then the police called to the BGB for backup.

Naziuddin watched as the scene unfolded: The BGB pulled up in trucks. Without issuing any kind of warning, he said, the men pulled out guns, leveled them into the crowd, and opened fire, using live bullets. The shooting continued without pause, Naziuddin said, describing automatic weapon fire.

“When I heard the shooting, I ran back into the field,” Naziuddin said. The protesters ran for shelter.

When the shooting subsided, Naziuddin saw his grandson lying on the ground. Syed had been shot on his right side, and the bullet passed through his body, Naziuddin said. “My grandson died on the spot,” he said. “I fainted when I saw him.”

Syed was one of six people killed from the village, Naziuddin said, giving Human Rights Watch the victims’ names. Syed was the youngest, at 12. The oldest was 24.

About 30 people were injured, Naziuddin reported. Many had been shot in the back as they ran away.

When Human Rights Watch asked Naziuddin if he had filed a complaint with the police, his shoulders drooped.

“We didn’t go to the police, but the next day we discovered the police had filed a case against us.” Both Naziuddin and his brother were charged with Syed’s death. About 50 people in the village, some the fathers and brothers of those killed, were also charged with at least one of the deaths, Naziuddin said. The charges paralyzed people with fear.

Naziuddin could not understand why he was charged. “I do not have a police record – no incidents. I am not a member of a political party.”

He was just a man who hoped for justice for his grandson’s death.

Your tax deductible gift can help stop human rights violations and save lives around the world.

Region / Country

Most Viewed

-

November 25, 2019

A Dirty Investment

-

-

April 22, 2024

Iran: Security Forces Rape, Torture, Detainees

-

June 24, 2022

Q&A: Access to Abortion is a Human Right

-

June 21, 2017

“Just Let Us Be”