Order this book from Amazon.com |

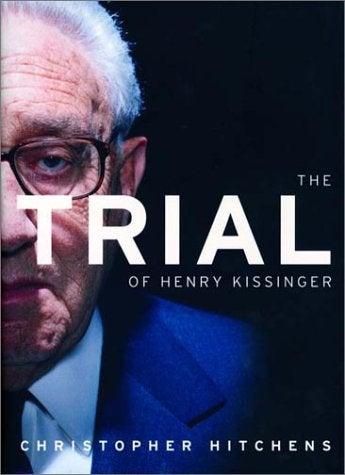

The Trial of Henry Kissinger

By Christopher Hitchens

Verso, London, 2001

Reviewed by Reed Brody

Special Counsel for Prosecutions

Human Rights Watch

History is catching up to former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. While he still pontificates regularly about world affairs on American news shows, it is increasingly a world he cannot visit. Judges from Argentina, Chile, France and Spain are seeking Kissinger's testimony regarding crimes committed by U.S. client regimes in South America in the 1970s. When Kissinger was in London in April, a British activist sought his arrest on charges related to the Vietnam War. Even in the United States, he is subject of a civil suit brought by the family of the Chilean military chief murdered in 1970 as part of a U.S.-conceived attempt to block the election of Salvador Allende.

Christopher Hitchens's book, though admittedly dripping with venom towards Kissinger, and at times rambling and unfocused, persuasively marshals the long-known, as well as the recently declassified, evidence to demonstrate Kissinger's role in the destruction of Chilean democracy and the consolidation of the Pinochet dictatorship, the prolongation of the Vietnam War through the sabotage of Lyndon Johnson's 1968 Vietnam peace talks, the Indonesian invasion and subsequent rape of East Timor, the Greek military junta's invasion of Cyprus in 1974, civilian deaths from United States' aerial bombing in Laos and Cambodia and the Pakistani army's crimes against humanity in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). Quite an impressive record for one man, even a Nobel Peace Prize Laureate.

So, is Henry Kissinger a war criminal?

It's difficult not to confuse political, moral and historical responsibility for great human suffering with criminal liability. But its one thing to say that Henry Kissinger's policies led to hundreds of thousands of deaths. It's another to say that, in a strict legal sense, he is criminally responsible for those deaths. Despite the title of his book, Hitchens doesn't try to separate the politically wrong from the criminally wrong or to make the legal case against Kissinger.

But there is a way to make a legal case. Traditional criminal law principles, as ratified by the Yugoslavia and Rwanda war crimes tribunals, hold that someone may be held liable as an accomplice if he consciously contributes to the perpetration of the crime in a material and substantial way. Under this standard, it would not be impossible to show that a U.S. (or Soviet) official whose support enabled a subservient regime to commit atrocities is an accomplice to those crimes. In the case of East Timor, for instance, newly released documents prove that, despite Kissinger's previous denials, he and President Ford specifically gave Suharto the green light to invade Timor in a Jakarta meeting only one day before the actual invasion. The United States was then supplying Indonesia's military with 90 percent of its arms, and Kissinger himself described their relationship as that of "donor-client." As the civilian death toll from the invasion mounted into the tens and later the hundreds of thousands, Hitchens and others charge Kissinger — knowing of the civilian slaughter — manipulated the Congressionally-mandated review process to ensure that aid to the killers kept flowing.

Where the United States committed the atrocities directly, the legal situation is different. For example, United States and South Vietnamese aerial bombings, on Kissinger's watch, left approximately 350,000 Laotian civilians and 600,000 Cambodian civilians dead. If Henry Kissinger indeed signed off on bombing targets in Cambodia and Laos knowing that civilians were present, as the accounts cited by Hitchens suggest, then the issue would be whether the bombing was indiscriminate or disproportionate.

It's hard to imagine, of course, that Kissinger would actually be brought to trial. As the abstract principle of individual criminal liability for atrocities becomes more of a reality, however, voices are increasingly heard asking why it is only the dictators of third world countries who are brought to justice and not the western leaders who put them in to power and sustained them while they committed their atrocities. Why is Pinochet brought to court and not Kissinger? Why Hissène Habré and not the American and French leaders who supported him throughout his rule? Why are Guatemalan strongmen charged with genocide but not the U.S. policymakers who supported them? Hitchens's book not only asks this question, it provides the factual fodder for responding "why not?"

BACK TO COMMUNITY: BOOK REVIEWS