|

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH PRISON PROJECT

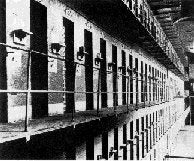

PRISONS IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA In many jails, prisons, immigration detention centers and juvenile detention facilities, confined individuals suffered from physical mistreatment, excessive disciplinary sanctions, barely tolerable physical

Fifty-three percent of all state inmates were incarcerated for nonviolent crimes, while criminal justice policies increased the length of prison sentences and diminished the availability of parole. The U.S. incarcerated a greater proportion of its population than any countries except Russia and Rwanda: more than 1.7 million people were either in prison or in jail in 1998, reflecting an incarceration rate of more than 645 per 100,000 residents, double the rate of a decade before. Approximately one in every 117 adult males was in prison. Surging prison populations and public reluctance to fund new construction produced dangerously overcrowded prisons. Violence continued to be pervasive: in 1997 (the most recent year for which data were available), sixty-nine inmates were killed by other inmates, and thousands were injured seriously enough to require medical attention. Extortion and intimidation were commonplace. Most inmates had scant opportunities for work, training, education, treatment or counseling. Mentally ill inmates—estimated to constitute between 6 and 14 percent of the incarcerated population—rarely received adequate monitoring or treatment. Many local jails were dirty, unsafe, vermin-infested, and lacked areas in which inmates could exercise or get fresh air. Some jail authorities placed inmates in restraining devices for long periods far in excess of legitimate safety considerations. Severe overcrowding coupled with inadequate staffing in many jails created dangerous conditions reflected in the numbers of inmates injured in fights, who experienced seizures and other medical emergencies without proper attention, and who managed to escape. Authorities relied increasingly on administrative segregation in super-maximum security prisons to maintain control. Prisoners deemed particularly disruptive or dangerous were isolated in small, often windowless cells for twenty-three hours a day; more than 24,000 prisoners were kept in this modern form of solitary confinement at any given time. At the end of 1997, Human Rights Watch released a report documenting conditions in two super-maximum security prisons in the state of Indiana. Although excessive use of physical force in these facilities had diminished in recent years, we still found excessive isolation, controls, and restrictions that were not penologically justified, and mentally ill inmates whose conditions were exacerbated by the regime of isolation and restricted activities, as well as by the lack of appropriate mental health treatment. The Indiana Department of Corrections instituted a number of reforms that were responsive to our concerns. Most significant was the development of a special housing unit for the treatment of disruptive or dangerous mentally ill inmates that opened in June 1998. Abusive conduct by guards was reported in many prisons. The threat of such abuse was particularly acute in supermax prisons. Since Corcoran State Prison in California opened in 1988, fifty inmates, most of them unarmed, were shot by prison guards and seven were killed. In February 1998, federal authorities indicted eight Corcoran officers for deliberately pitting unarmed inmates against each other in gladiator-style fights which the guards would then break up by firing on them with rifles. In July, the state announced a new investigation into at least thirty-six serious and fatal shootings of Corcoran inmates. Guard abuse was by no means confined to California prisons. Across the country, inmates complained of instances of excessive and even clearly lawless use of force. In Pennsylvania, dozens of guards from one facility, SCI Greene, were under investigation for beatings, slamming inmates into walls, racial taunting and other mistreatment of inmates. The state Department of Corrections fired four guards, and twenty-one others were demoted, suspended or reprimanded. In many other facilities across the country, however, abuses went unaddressed. Overcrowded public prisons and the tight budgets of corrections agencies fueled the growth of private corrections companies: approximately 100,000 adults were confined in 142 privately operated prisons and jails nationwide. Many of these facilities operated with insufficient control and oversight from the public correctional authorities. States failed to enact laws setting appropriate standards and regulatory mechanisms for private prisons, signed weak contracts, undertook insufficient monitoring and tolerated prolonged substandard conditions. In less than a year, there were two murders and thirteen stabbings at one privately operated prison in the state of Ohio. Sexual and other abuses continued to be serious problems for women incarcerated in local jails, state and federal prisons, and INS detention centers. Women in custody faced abuses at the hands of prison guards, most of whom are men, who subjected the women to verbal harassment, unwarranted visual surveillance, abusive pat frisks and sexual assault. Fifteen states did not have criminal laws prohibiting custodial sexual misconduct by guards, and Human Rights Watch found that in most states, guards were not properly trained about their duty to refrain from sexual abuse of prisoners. The problem of abuse was compounded by the continued rapid growth of the female inmate population. As a result women were warehoused in overcrowded prisons and were often unable to access basic services such as medical care and substance abuse treatment. In Michigan, where women were plaintiffs in a civil rights suit jointly litigated by private lawyers and the Department of Justice, these women reported retaliatory behavior by guards, as described in more detail below. The retaliation ranged from verbal abuse, intimidation, and excessive and abusive pat frisks, to loss of visitation privileges and "good time" accrued toward early release. Men in prison also suffered from prisoner-on-prisoner sexual abuse, committed by fellow inmates. Prison staff often allowed or even tacitly encouraged sexual attacks by male prisoners. Despite the devastating psychological impact of such abuse, there were few if any preventative measures taken in most jurisdictions, while perpetrators were rarely punished adequately by prison officials. As in previous years, increasing numbers of children were incarcerated nationwide, even as the number of violent juvenile offenders fell. Research by the Department of Justice's Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) found that only 6 percent of juvenile arrests in 1992 and 1994 were for violent crimes. Between 1994 and 1995, according to OJJDP, violent crime arrests of juveniles between the ages of fifteen and seventeen fell by 2 percent; arrests of younger juveniles for violent crimes dropped by 5 percent for the same period. Despite this declining percentage of violent juvenile offenders, and in spite of the costs associated with incarceration, most states continued to incarcerate high numbers of children for nonviolent offenses. Between 1992 and 1998, at least forty states adopted legislation making it easier for children to be tried as adults, and forty-two states detained juveniles in adult jails while they awaited trial. Prompted by a 1996 Human Rights Watch report on human rights abuses in the state of Georgia, the Department of Justice (DOJ) concluded a year-long investigation of the state's juvenile detention facilities in February 1998. The DOJ identified a "pattern of egregious conditions" that violated children's rights, including overcrowded and unsafe conditions, physical abuse by staff and excessive use of disciplinary measures, inadequate educational, medical and mental health services. In March 1998, the state and the DOJ signed an agreement that required the state to make extensive improvements. The DOJ concluded at least two other investigations of juvenile facilities in 1998, finding violations in the county detention centers in Owensboro, Kentucky, and Greenville, South Carolina. In each of these facilities, the DOJ found evidence that staff employed excessive force against juvenile inmates. Human Rights Watch reports on U.S. prisons:

From the California State Senate hearings on Corcoran State Prison: The following online articles discuss recent developments with regard to prisons in the United States:

The following organizations work to ensure that U.S. prisoners are treated humanely and are confined in at least minimally adequate conditions:

State and federal governmental prison sites:

Other useful sources of information on conditions, treatment, legal standards, and other issues relevant to U.S. prisons and jails:

[Back to the Human Rights Watch Prison Conditions Page] |