Glossary of Armed Forces and Groups in Eastern Congo

A number of non-state armed groups, as well as the Congolese armed forces, committed serious abuses against civilians in eastern Congo between 2012 and 2014. Some of these groups are described below. Groups are listed in alphabetical order. Dozens of other armed groups are also active in eastern Congo.

Allied Democratic Forces (ADF)

The Allied Democratic Forces is a Ugandan-led Islamist armed group that has been active in North Kivu’s Beni territory since 1996. ADF fighters, including Ugandans and Congolese, have been responsible for killings of civilians and scores of kidnappings in recent years.

Civilians who had earlier been held in ADF camps said they saw deaths by crucifixion, executions of those trying to escape, and people with mouths sewn shut for allegedly lying to their captors. Some captives accused of “misbehaving” were held in holes or in a casket lined with nails for days or more than a week. The attackers also raped women and forced them to be their “wives.”

Congolese Armed Forces (FARDC)

Created in 2003, the national Congolese army (Forces armées de la République Démocratique du Congo), with an estimated strength of at least 120,000 personnel, has a long record of abuse. To a large extent, this reflects the lack of accountability for abuses and the government’s practice of integrating former fighters from armed groups into the army without formal training or vetting for their involvement in past human rights abuses. In the context of operations against armed groups in eastern Congo between 2012 and 2014, soldiers were responsible for summary executions, rapes, arbitrary arrests, and mistreatment of suspected armed group collaborators.

Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR)

The Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (Forces démocratiques pour la libération du Rwanda) has been one of the most abusive armed groups in eastern Congo over the past two decades. The group is largely made up of Rwandan Hutu, some of whom participated in the genocide in Rwanda in 1994. Many fled Rwanda towards the end of the genocide in 1994 and have remained in eastern Congo ever since. FDLR combatants have been responsible for widespread war crimes in eastern Congo, including ethnic massacres, mass rapes, and forced recruitment of children. The group’s military commander, Sylvestre Mudacumura, a Rwandan who has commanded the FDLR’s military forces since 2003, is sought on an arrest warrant from the International Criminal Court (ICC) for war crimes committed in eastern Congo.[1] The FDLR’s strength has significantly decreased in recent years—from an estimated 6,000 fighters in 2008 to an estimated 1,000-1,500 in 2015—as a result of military pressure and demobilization efforts. However, the FDLR continues to attack civilians in eastern Congo, often in alliance with Congolese Hutu armed groups, including Nyatura (see below).

M23

The M23 was led by mostly Tutsi officers who had been part of a previous rebellion, the National Congress for the Defense of the People (Congrès national pour la défense du peuple, CNDP), before integrating into the army in early 2009, then defecting in early 2012. The name comes from the March 23, 2009 agreement with the Congolese government. The M23 relied on significant support from Rwandan military officials who planned and commanded operations, trained new recruits, and provided weapons, ammunition, and other supplies. Hundreds of young men and boys were recruited in Rwanda and forced to cross the border into Congo and fight with the M23. Between April 2012 and November 2013, when the group was defeated, M23 fighters committed widespread war crimes, including summary executions, rape, and recruitment of children, including by force.

Mai Mai Kifuafua

Mai Mai Kifuafua is a largely ethnic Tembo local defense group that has operated in southeastern Walikale, southwestern Masisi, and northern Kalehe territories. One of the group’s main leaders is Delphin Mbaenda. In 2012, Mai Mai Kifuafua fighters allied with the Raia Mutomboki in attacks against Hutu civilians in southern Masisi and Walikale territories, deliberately killing at least several hundred civilians. After a dispute between Mai Mai Kifuafua and Raia Mutomboki leaders in early 2013, Kifuafua combatants carried out a series of attacks against the Raia Mutomboki and civilians living in areas under their control.

Mai Mai Simba

Mai Mai Simba is one of the oldest armed groups in eastern Congo, with its origins dating back to 1963. It is a largely ethnic Kumu armed group with, in 2014, an estimated 75 combatants based in Maiko Park in Walikale territory and parts of Maniema province, where its fighters are involved in poaching elephants for ivory and mining gold in the Osso River. Following disputes with Mai Mai Sheka over control of mining sites in 2013, Mai Mai Simba fighters committed serious abuses against artisanal gold miners and other civilians accused of collaborating with or supporting Mai Mai Sheka.

Nduma Defense of Congo (Mai Mai Sheka)

The Nduma Defense of Congo (NDC), also known as Mai Mai Sheka, has been responsible for extremely brutal attacks on civilians in Walikale and northwestern Masisi in recent years. Led by Ntabo Ntaberi Sheka, a former minerals trader, the group is primarily made up of ethnic Nyanga combatants. Sheka fighters have killed dozens of civilians. Most of the victims were Hutu and Hunde civilians; many were hacked to death by machete. Sheka combatants desecrated corpses and paraded through towns with body parts of those they had killed, shouting that they were going to “exterminate” all Hutu and Hunde. Sheka fighters have also raped and tortured hundreds of civilians. Girls as young as 12 have been forced to serve as sex slaves for Sheka’s fighters. Many Sheka fighters are children or former children who were recruited by force.

Nyatura

With the start of the M23 rebellion and the rise of the Raia Mutomboki phenomenon (see below) in early 2012, Congolese Hutu armed groups spread throughout Masisi and parts of Rutshuru, Walikale, and Kalehe territories. New groups were formed and older groups re-established themselves. While many of these groups have their own individual names or are named after their commanders, they are often referred to collectively as the Nyatura, which means “hit hard” in Kinyarwanda, the language of Rwanda. Nyatura fighters, often operating together with the FDLR, were responsible for widespread abuses, including summary executions, rapes, and recruitment of children, including by force.

People’s Alliance for a Free and Sovereign Congo (APCLS)

The People’s Alliance for a Free and Sovereign Congo (Alliance du peuple pour un Congo libre et souverain) is a largely ethnic Hunde armed group led by Janvier Buingo Karairi, which largely operates in the area north of Nyabiondo, in western Masisi territory. The group’s leaders claim they are protecting the Hunde population from what they describe as a “Tutsi invasion” and occupation of western Masisi. The APCLS has been responsible for serious abuses in areas they control and during operations against opposing forces, including rapes, abductions, burning of homes, illegal detention, torture, mistreatment, and forced recruitment of children. They have sometimes operated side by side with the FDLR and Nyatura.

Raia Mutomboki

The Raia Mutomboki (“outraged people” in Swahili) is a loosely organized network of former militia fighters, demobilized soldiers, and youth who armed themselves largely with machetes and spears to protect civilians from the FDLR, while also gaining control of mining areas and illegal taxation networks. The Raia Mutomboki often avoided direct clashes with the FDLR, and instead focused their attacks first on the FDLR’s dependents and Rwandan Hutu refugee women and children living in eastern Congo, and later on the Congolese ethnic Hutu population. In 2012, Raia Mutomboki combatants killed hundreds of civilians by hacking them to death with machetes and burned dozens of villages to the ground.

Summary

“When a fighter knocks on the classroom door, you have to answer.… He asked for a girl student. I couldn’t refuse. So I called the girl he named, and she went with him. He didn’t have a gun, but his escorts were behind him, and they had guns.”

—Teacher, Rutshuru territory, July 2013

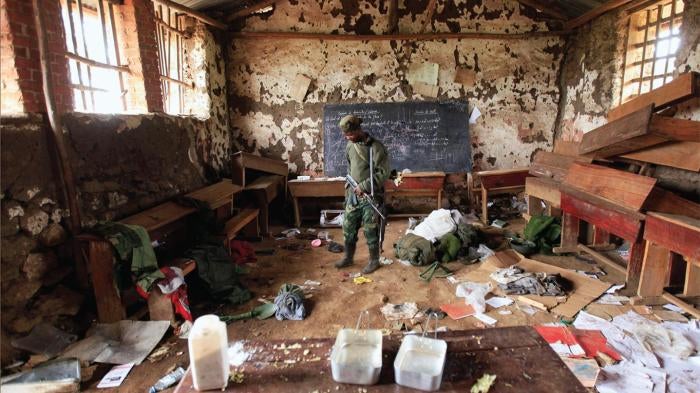

The first time the M23 [rebels] came to attack, the FARDC [Congolese Army] had occupied our school…. And when the FARDC had been driven out by the M23, then the M23 also occupied our school…. Our school became the battlefield.

—Local resident, Rutsiro, January 2014

For many children in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo who yearn to study, armed men in their schools is an all too familiar sight. As the country grapples with ongoing fighting among various armed groups and the Congolese army (Forces armées de la République Démocratique du Congo, FARDC), abuses by troops in and around schools has serious consequences for the safety of students, teachers, and administrators, as well as students’ ability to learn.

This report documents how schools have come under attack from armed groups engaged in eastern Congo’s armed conflicts. Warring parties have also unlawfully recruited children, including by force, from schools or while on the way to school, to use either in combat operations or in support roles. They have abducted countless girls from schools to be raped or kept as “sex slaves.” Fear of abduction and sexual violence keeps many children from attending school. Parents have also kept children from schools out of concern that armed groups will target them for unofficial “taxes” imposed on civilians.

Both the Congolese army and non-state armed groups have also taken over schools for military purposes. Sometimes, they take over a few classrooms or the playground; at other times armies convert an entire school into a military base, barracks, training grounds, or weapons and ammunition storage. Troops occupying schools expose students and teachers to risks such as unlawful recruitment, forced labor, beatings, and sexual violence.

The military use of schools deteriorates, damages, and destroys already insufficient and poor quality education infrastructure. Fighters who occupy schools frequently burn the buildings’ wooden walls, desks, chairs, and books for cooking and heating fuel. Tin roofs and other materials may be looted and carted off to be sold for soldiers’ personal gain.

The use of a school for military deployments can result in additional damage to the building because it makes the school a legitimate target for enemy attack. Even once vacated, the school may still be a dangerous environment for children if troops leave behind weapons and unused munitions.

In a country that already suffers from inadequate opportunities to access quality education, such damage to schools due to military use further hampers students’ educational prospects and their futures.

According to the Congolese Ministry of Education, eastern Congo’s North Kivu province had the highest proportion of school-aged children out of school compared to the country’s other provinces in 2012: a child living in North Kivu is more likely to never attend a school than a child born anywhere else in the country. Although children in South Kivu fare slightly better, fear of crime and conflict in both provinces is frequently cited as a reason for children to drop out of school, or to never go in the first place.

During times of conflict and insecurity, maintaining ongoing access to education is of vital importance for children. If they remain safe and protective environments, schools can provide an important sense of normalcy that is crucial to a child’s development and psychological well-being. Schools can also help provide important safety information and services. Parents throughout Congo constantly demonstrate the value they place on their children receiving an education, scraping together the resources to pay fees and other costs necessary to enroll their children. Even when schools are damaged or destroyed, communities often devise alternative solutions for themselves, teaching children in churches, or in makeshift structures constructed from nothing more than sticks and tarpaulins.

Since many schools in eastern Congo are constructed using funds collected from local community members rather than government appropriations, the loss of education infrastructure constitutes a very immediate and concrete loss of community investment that extends into the future through the ongoing loss of children’s education.

The Congolese government should impartially investigate and appropriately prosecute army officers and armed group commanders responsible for the recruitment or abduction of children and other violations of international human rights and humanitarian law, including unlawful attacks on schools, students and teachers.

In line with United Nations Security Council Resolution 2225, the Congolese government should also take concrete measures to deter the military use of schools. It should swiftly join the Safe Schools Declaration—endorsed by 49 countries as of October 2015—which commits to protect education from attack. And it should review its military policies, practices, and training to ensure that they, at a minimum, conform with protections provided for in the Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict, which provide guidance on how parties to armed conflict should avoid impinging on students’ safety and education.

* * *

This report is based on interviews with more than 120 people, including students, teachers, parents, school administrators, village officials, religious leaders, Ministry of Education officials, UN officials, and members of Congolese and international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) based in North and South Kivu.

Attacks on schools and their use for military purposes by fighters rose sharply in early 2012, when the emergence of a major new rebel group—the M23—led to intensified operations by the Congolese army, as well as a rise in activity and attacks on civilians by numerous other armed groups in North and South Kivu. The 19-month rebellion ended in early November 2013, after the Congolese army and UN peacekeeping forces—including a new international Intervention Brigade mandated to neutralize armed groups—defeated the M23’s forces on the battlefield.

However, the military defeat of the M23 did not bring about the end of hostilities in North and South Kivu, as many other armed groups continue to operate in the provinces.

Human Rights Watch documented attacks on schools or the use of schools for military purposes by the Congolese army, the M23, various Congolese Hutu militia groups known as the Nyatura, Mai Mai Sheka and other Mai Mai groups, and the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (Forces Démocratiques pour la Libération de Rwanda, FDLR), a largely Rwandan Hutu armed group, some of whose members participated in the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. Throughout Congo in 2013 and 2014, the UN verified attacks on schools, looting of schools, or military use of schools by the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), the Congolese army, the FDLR, the Front for Patriotic Resistance in Ituri (FRPI), M23, Mai Mai LaFontaine, Mai Mai Yakutumba, Nyatura groups, the People’s Alliance for a Free and Sovereign Congo (Alliance du peuple pour un Congo libre et souverain, APCLS), the Raia Mutomboki, and the Union of Congolese Patriots for Peace (Union des patriotes congolais pour la paix, UPCP).

Attacks on schools not being used for military purposes that are deliberate or indiscriminate are violations of international humanitarian law, or the laws of war. Those who commit or order such attacks with criminal intent are guilty of war crimes.

The military use of schools can also result in violations of international humanitarian and human rights law. The laws of war require that all parties to a conflict take all feasible precautions to protect the civilian population and civilian objects, such as schools, under their control against the effects of attacks. Moreover, each party to a conflict must remove, to the extent feasible, civilians under its control from the vicinity of military objectives. Thus, it is unlawful to use a school simultaneously as a military base, barrack, or firing position, and also as an educational center.

Moreover, international human rights law, which is applicable in both times of war and peace, guarantees the right of students to education. Since the extended use of a school by armed forces or armed groups affects children’s ability to attend classes in an environment conducive to learning, this poses a threat to their right to education as guaranteed under international human rights law, as well as under the Congolese constitution. Even brief use of schools, however, can render schools essentially inoperative.

There has been increased attention paid both domestically and internationally to the negative consequences of the military use of schools. The Congolese army and Ministry of Defense have begun to explore the development of explicit protections for schools from military use. Following the occupation by Congolese army soldiers of dozens of schools in the area around Minova after the M23 rebel group took control of Goma in November 2012, the North Kivu military commander ordered all soldiers to vacate the schools.

In early 2013, Congo’s Minister of Defense at the time, Alexandre Luba Ntambo, issued a ministerial directive to the Congolese army stating that all military personnel found guilty of requisitioning schools for military purposes would face severe criminal and disciplinary sanctions. However, Human Rights Watch is unaware of any existing legislation or military doctrine that explicitly prohibits or regulates the practice of military use of schools, let alone that makes it a criminal offense.

As Congo’s children struggle to recover from the trauma of violence in their villages, homes, and schools, the government has the primary responsibility to ensure that communities that have lost school infrastructure due to occupation and use by government forces and armed groups have the resources to repair and rebuild educational institutions.

The government should also help protect children from future incursions on their schools by enacting domestic legislation or regulations explicitly banning armed forces and armed groups from using or occupying schools, school grounds, or other educational facilities in a manner that would endanger civilians or civilian objects, or that would violate children’s right to education under international human rights law. This would be in line with UN Security Council Resolution 2225, adopted in June 2015, which encourages all states to take concrete measures to deter the military use of schools.

Non-state armed groups should also adopt and publish policies banning the use of schools by their forces.

Children’s access to education is more often a fight than a right in many parts of Congo. Bringing students back to school is vital for children’s protections and should be at the heart of efforts to build a durable peace in Congo.

Recommendations

To the Congolese Government

- Impartially investigate and appropriately prosecute Congolese army officers and armed group commanders responsible for recruiting or abducting children and other violations of international human rights and humanitarian law, including unlawful attacks on schools, students, and teachers.

- In accordance with UN Security Council Resolution 2225, take concrete measures to deter the military use of schools. Enact legislation prohibiting Congolese armed forces and non-state armed groups from using or occupying schools, school grounds, or other education facilities in a way that violates international humanitarian law, including the obligation to take all feasible precautions to protect civilians against the effects of attacks.

- Ensure that students deprived of educational facilities as a result of armed conflict are promptly given access to accessible alternative schools, including with suitable school equipment, while their own schools are repaired or reconstructed.

- Ensure that teachers and students, and women and girls generally, who experience rape and sexual violence receive trauma support and ongoing counseling, as well as immediate access to treatment for injuries, emergency contraception, safe and legal abortion services, and access to sexual and reproductive health and psychosocial support. Develop a plan to assist children born from rape to ensure adequate services and protection for them and their mothers.

- Endorse the Safe Schools Declaration, thereby committing to use as a minimum standard the Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict.

To the Congolese Army

- Order commanding officers not to use school buildings or school property for camps, barracks, deployment, or weapons, ammunition, and supply depots where it would unnecessarily place civilians at risk or deprive children of their right to education. Draw upon examples of good practice, as reflected in the Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict.

To All Armed Groups

- Cease the abduction and recruitment, forced or otherwise, of anyone under age 18 into the armed group for any purpose. Appropriately punish any commander who engages in such practices.

- Release everyone in the armed group under 18 and ensure their safe return by acting in cooperation with UN agencies; permit anyone recruited under age 18 to leave armed groups.

- Order commanders not to use school buildings or school property for camps, barracks, military deployments, or weapons, ammunition, and supply depots where it would unnecessarily place civilians at risk or deprive children of their right to education.

- Draw upon examples of good practice, including by other non-state armed actors, as reflected in the Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict.

To the UN Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO), the Education Cluster, and UN Country Team

- Continue to monitor, report, and respond to attacks on schools, military use of schools, and abductions and recruitment of children. Conform monitoring and reporting of attacks on students, teachers, and schools, and military use of schools with the “Guidance Note on SCR 1998 (2011)” issued in 2014 by the Special Representative to the Secretary-General on Children and Armed Conflict, in order to ensure better and more consistent data.

- Continue to advocate with the Congolese army and all armed groups who use schools for military purposes to vacate schools and ensure that students return to them in safety.

- Work with the army and all armed groups with which action plans have been concluded or are negotiated to respond to both attacks on schools and military use of schools.

- Work with the army and any armed group identified as using schools for military purposes to develop concrete measures to deter such use.

To Countries that Provide Military Training and Assistance to the Congolese Armed Forces, including Belgium, China, France, South Africa, and the United States

- Share examples of good practice in avoiding the use of schools for military purposes, and provide trainings that utilize the Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict.

To Donor Governments and UN Agencies

- Publicly denounce attacks on schools and illegal use of schools for military purposes by the Congolese army and armed groups and call for those responsible to be impartially investigated and appropriately prosecuted.

- If providing support for the reconstruction of schools or the education sector generally, urge the government to adopt strong protections for schools from military use.

- Privately and publicly urge the Congolese government and army to adopt the above recommendations.

Methodology

This report is based on Human Rights Watch interviews with more than 120 people, including 19 children, ages 10 to 17, conducted between June and July 2013, and additional research by Human Rights Watch in the region since then. It covers incidents that occurred between April 2012 and December 2014 in North and South Kivu provinces.

Human Rights Watch interviewed students, teachers, parents, school directors, village officials, religious leaders, Ministry of Education officials, UN officials, and members of local and international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). Interviews were carried out in safe, discreet locations in or near population centers.

Pseudonyms are used for all children quoted in this report. Due to security concerns, the names of many adult interviewees have also been withheld. All interviews were conducted on the basis of informed consent. No one was provided compensation for being interviewed.

This report focuses on abuses affecting education by Congo’s national army and non-state armed groups in eastern Congo, and thus does not address many other factors influencing education access and quality, including the state’s commitment to the right to education and the use of schools in eastern Congo to provide shelter to displaced persons.

I. Background

Armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo over the past two decades, primarily in the eastern part of the country, has resulted in the deaths of an estimated five million people to violence, fighting, hunger, and disease. Combatants from dozens of Congolese and foreign armed groups and soldiers from the Congolese army, as well as the Rwandan and Ugandan armies, have carried out massacres, rapes, summary executions, torture, pillage, arson, and recruitment of children into their forces. The use of rape as a tactic of war has particularly marked the conflicts, with hundreds of thousands of women and girls experiencing sexual violence.

Conflict in North and South Kivu 2012-2015

Armed conflict continued in eastern Congo from 2012 through 2015, with the Congolese army and various armed groups responsible for numerous serious abuses against civilians.

Fighting Between M23 Rebels and Congolese Army

In March 2012, Bosco Ntaganda, a former rebel who had become a general in the Congolese army, defected from the army with several hundred former members of the National Congress for the Defense of the People (Congrès national pour la défense du peuple, CNDP) rebel group. The mutiny began soon after the government indicated that it was planning to deploy ex-CNDP soldiers outside of North and South Kivu. A parallel military structure had been established in North and South Kivu with troops loyal to Ntaganda responsible for targeted killings, mass rapes, abductions, robberies, and resource plundering. Ntaganda’s troops forcibly recruited at least 149 people, including at least 48 children, in Masisi, North Kivu, in April and May 2012.[2]

Soon after Ntaganda’s mutiny was defeated by the Congolese army in April, other former CNDP members led by Col. Sultani Makenga launched another mutiny in Rutshuru territory, North Kivu. Ntaganda and troops loyal to him joined this new rebellion.[3]

The M23 rebellion received significant support from Rwandan military officials, including in the planning and command of military operations and the supply of weapons and ammunition. At least 600 young men and boys were recruited by force or under false pretenses in Rwanda to join the rebellion.[4]

During their 12-day occupation of the eastern city of Goma and the town of Sake in November 2012, M23 fighters summarily executed at least 24 people, raped at least 36 women and girls, looted hundreds of homes, offices, and vehicles, and forcibly recruited army soldiers and medical officers, police, and civilians into its ranks.[5]

As government soldiers fled the M23 advance on Goma, they went on a rampage and raped at least 76 women and girls in and around the town of Minova, South Kivu, according to Human Rights Watch research. The M23 withdrew from Goma on December 2 when the government agreed to start peace talks in Kampala, Uganda.[6]

Following infighting within the M23, Bosco Ntaganda surrendered to the US embassy in Rwanda in March 2013. As of September 2015, he stands trial at the International Criminal Court on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in 2002 and 2003.[7]

The M23 was defeated in November 2013 after international pressure on the group’s Rwandan backers and the deployment of a United Nations “Intervention Brigade” to conduct offensive operations against armed groups and strengthen the UN peacekeeping mission. Several thousand fighters from other armed groups surrendered in the weeks that followed.

On December 12, 2013, the M23 and the Congolese government signed declarations in Nairobi marking an end to the M23 rebellion and the conclusion of the 12-month-long Kampala talks. The declarations included commitments to disarm, demobilize, and reintegrate former M23 members, and not to give an amnesty to those responsible for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

But the government has stalled in implementing a new Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (DDR) program for former combatants, and there were few efforts made to bring to justice M23 and other armed group leaders implicated in abuses. At time of writing, most former M23 fighters were still in Uganda and Rwanda and their leaders remained at large.[8]

Attacks on Civilians by Other Armed Groups

As the Congolese military focused attention on defeating the M23, numerous other armed groups carried out horrific attacks on civilians in North and South Kivu. They include the Raia Mutomboki, the Nyatura, Mai Mai Sheka, Mai Mai Kifuafua, and the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (Forces démocratiques pour la libération du Rwanda , FDLR).[9]

Combatants from an armed group called the Raia Mutomboki massacred entire families with machetes and spears, specifically targeting Hutu civilians. Fighters of another armed group, Mai Mai Sheka, abducted young schoolchildren, marched them through the forest, and killed those who were too tired or weak. They have also killed and mutilated civilians and held dozens of girls as sex slaves. FDLR fighters rounded up and gang-raped women and girls, some as young as 7, attacking them so brutally that some died from their wounds. Congolese army forces deployed on operations to fight these armed groups have in turn attacked the civilians they were meant to protect.

Education in North and South Kivu

Congo’s constitution guarantees that everyone has the right to education, and that primary education—which lasts six years and is aimed at 6 to 11 year olds—is both free and compulsory in public schools.[10] Unfortunately, the reality is far from this promise.

There are four categories of schools in Congo: 1) schools under the direct control of the government; 2) so-called “network schools,” also known as “government-regulated schools” or “conventionized schools,” which are usually run by religious or social groups by agreement with the government; 3) private schools accredited by the government; and 4) private schools not accredited by the government. The first two types of schools are generally considered as public government schools, with the “network schools” responsible for the majority of children. The government is responsible for paying teachers and administrative staff at public schools, although the “network schools” hire their own teachers and also sometimes mobilize other resources, generally from the local community, for instance, to build infrastructure. A comparison between the total education expenditure of households in 2010 to 2011 with the total budget of the Ministry of Education during the same time showed that households spent nearly three times more than the government did on education.[11] As one school director from Kalehe told Human Rights Watch, “Parents contribute for everything.”[12]

The education sector has been severely negatively affected by the country’s various crises over the past decades, especially in terms of government investment.[13] In 2010, the Congolese government decreed a gradual transition towards free primary education, but the elimination of school tuition, registration fees, and other related costs is not universal, and these fees remain a barrier for many families. As one parent who is a member of a school committee told Human Rights Watch, “Parents do not have money to pay school fees.”[14] Another parent explained, “I had children at the schools, but I no longer have any money to pay their school fees, so they don’t study anymore.”[15]

According to a 2012 survey by Congo’s Ministry of Primary, Secondary, and Vocational Education, the proportion of 5 to 17 year olds who are out of school (that is, have either never enrolled in school or who have dropped out) is estimated at 29 percent.[16] For 6 to 11 year olds—children who should be in compulsory primary education—27 percent are out of school.[17] Girls account for more than half of those not enrolled.

The statistics for North Kivu are particularly grim. North Kivu has the nation’s highest proportion of 5 to 17 year olds out of school, at 44 percent. South Kivu is the fifth worst affected region, with 30 percent out of school.[18] For children of primary school age, North Kivu again has the highest proportion out of school for anywhere in the country, at 40 percent, while South Kivu is the country’s fifth worst region, with 27 percent out of school.

A child living in North Kivu is more likely to never attend a school than a child born anywhere else in the country—only 79 percent will enter school any time before turning 12.[19] And a child who does enroll in school in North Kivu has the highest chance of failing to complete 12 years of schooling (40 percent drop out) than anywhere else in the country; South Kivu ranks third worst, at 37 percent of children dropping out.[20]

Various factors explain low enrollment and high drop-out rates in Congo, including low income and educational levels of some parents, early and child marriage, child labor in agriculture and mining, insufficient funding for education, and not enough places at schools. However, according to the 2012 survey, 16 percent of children in South Kivu and 8 percent in North Kivu who dropped out of school did so—at least in part—due to concerns about “fear of crime/conflict.” Indeed, in South Kivu, it was the third most mentioned reason for a child to drop out of school, after “money” and “family constraints.” Reversing positions, 15 percent of respondents in North Kivu and 10 percent in South Kivu cited “fear of crime/conflict” for why children have never gone to school. In North Kivu, this was the third most cited reason after “money” and “no school nearby.” Again, North and South Kivu topped the nation in percentage of children who had never gone to school out of “fear of crime/conflict.”[21]

New fighting in North Kivu in 2012 led to a sharp jump in children whose schooling was affected by the conflict. According to UNICEF, the UN’s children’s agency, at least 240,000 students missed weeks of schooling as a result of the conflict between April and December 2012.[22]

It is against this bleak education outlook that attacks on schools and the military use of schools makes a bad situation worse.

II. Attacks on Students and Schools

When war came, [Ntabo Ntaberi] Sheka didn’t want the schools in Masisi to function… He said “There’s no school better than this weapon!”

—Parent from Pinga, July 2013

On October 4, 2012, the Congolese government adopted an action plan for the prevention of recruitment and use of children, sexual violence, and other grave violations against children by the national armed forces and other state security forces. In July 2014, the government appointed Jeannine Mabunda Lioko Mudiayi as a presidential adviser on conflict-related sexual violence and child recruitment. The government has worked together with United Nations child protection agencies to remove child soldiers from the army and to prevent integration of children from armed groups into the army.

However, as documented in this chapter, numerous armed groups have attacked schools, students, and teachers; looted schools; and abducted and recruited children from school grounds, or while students are on their way to or from school. According to UN documentation and Human Rights Watch research, between 2012 and 2014, the M23, the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (Forces démocratiques pour la libération du Rwanda, FDLR), Nyatura groups, Mai Mai Sheka, the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), the People’s Alliance for a Free and Sovereign Congo (Alliance du peuple pour un Congo libre et souverain, APCLS), Mai Mai Yakutumba, Mai Mai La Fontaine, the Front for Patriotic Resistance in Ituri (FRPI), and the Union of Congolese Patriots for Peace (Union des patriotes congolais pour la paix, UPCP) have committed such abuses in eastern Congo.[23]

Fear of abduction from school, or while en route, can keep students from attending classes. A school official named seven of his students abducted by Bosco Ntaganda’s fighters while returning home from school in April 2012. “Having learned of this,” the school official said, “all the other students were afraid to attend school.”[24]

Abduction of Children from School by Mai Mai Sheka

On September 27, 2013, Mai Mai Sheka fighters attacked the primary school in Butemure village, in western Masisi territory, abducted about 20 students, and used sticks and bayonets to beat children who tried to escape, seriously injuring at least six of them. Sheka fighters also looted the school, and another primary school in Lwibo, as well as the health center in Butemure.[25]

For the next six days, the fighters marched with the children and other abductees, through the forest from Lwibo to Pinga.[26]

A 6-year-old girl told Human Rights Watch how she was wounded by Sheka fighters:

I saw people coming with weapons and we started to flee. In the schoolyard, one of the fighters hit me with his gun and I fell. When I came to and got up to leave, no one was left in the schoolyard. They had hit me in the back of my head and there was blood everywhere. I went to my house, but I couldn’t find my mother or father. I then went to the place where we usually hide near our farm and I found my aunt there. She used plant leaves to treat the wound.[27]

While some people escaped along the journey, at least one abducted child was killed by Sheka fighters before they reached Pinga. A 6-year-old girl who was abducted in Lwibo told Human Rights Watch how a young boy was killed during the journey because he could not walk fast enough. “They cut him in his head with a machete, and then threw his body in the river,” she said. Sheka fighters later stabbed the girl in the foot and near her right eye, but she survived.[28]

A 22-year-old Hunde woman who escaped told Human Rights Watch that one fighter said, “Any child who is tired and can’t continue will be killed like the other child who was just killed back there.”[29]

A 48-year-old woman who was abducted in Lwibo told Human Rights Watch:

When we didn’t march fast enough, they beat us with sticks and the butts of their guns to force us to go faster. Those who were in good shape could go faster than those of us who were older. Some children were tired, and I think they killed some of them. I heard the voice of one child crying out, ‘Mama wee’ [a cry for help in Swahili used by small children], and then we never saw that child again. He was about 6 years old.[30]

Only 12 child and 2 adult abductees eventually made it to Pinga on October 3.[31] There, they were held for two weeks until released following interventions by the UN Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) and other international organizations.

Witnesses and a former Sheka combatant told Human Rights Watch that one of the leaders of the attack was a Mai Mai Sheka commander known as “Tondeuse.”[32] Witnesses said that Raia Mutomboki combatants allied with Mai Mai Sheka also participated in the attack.[33]

An October 2013 UN report on child recruitment by armed groups noted allegations that 30 to 40 percent of Nduma Defense of Congo (NDC)/Sheka elements under the leadership of Ntabo Ntaberi Sheka were under 18, and that children rarely succeed in surrendering or escaping as the punishment for leaving the group is allegedly a bullet to the knee or decapitation.[34]

Recruitment of Children from Schools by the M23

When Bosco Ntaganda and those loyal to him defected from the Congolese army in March 2012, before the start of the M23 rebellion, they told civilians in Masisi territory that children and young men were needed for their forces. A woman told Human Rights Watch that Ntaganda came to Birambizo village and said, “Since you [villagers] have been with the government, you’ve gotten nothing. Why not join me?” The woman explained,

“[Ntaganda] asked us to give our children, our students, to him to fight. He came to our village himself.... But we refused and said our children should go to school.”

In the days that followed, Ntaganda’s fighters took children by force from schools as well as from their homes, farms, or the roadside as they tried to flee on foot or on motorbike taxis. A number of those forcibly recruited were given rudimentary military training, but the majority was immediately forced to porter weapons and ammunition to frontline positions. Many were made to wear military attire.

Near Kingi, Masisi territory, on April 19, 2012, Ntaganda’s forces rounded up at least 32 male students at Mapendano secondary school. A 17-year-old student told Human Rights Watch:

When the soldiers arrived at our school, some students fled, but the soldiers surprised us and some of us were unable to flee. They told us there was a message they were bringing to our school. All the rest of the students gathered on the playground, and they separated the oldest and the youngest as well as the girls…. I found myself in the exempted group. All the older students were asked to go with them…. The soldiers told them that other young people like them were fighting for the liberation of the country, and even dying, “And you! You say you are studying! What is that? Come on, help others to fight!”[35]

One student explained how some of the students have subsequently returned home, “but have never attended school again for fear of being caught another day at the school by soldiers.”[36]

Human Rights Watch documented that Ntaganda’s forces forcibly recruited at least 149 boys and young men into his forces between April 19 and May 16, 2012.[37] Students were also abducted by the M23 after the rebellion was officially established. In July and August 2012, at least 137 young men and boys were forcibly recruited in Rutshuru territory, including at least 20 children under 18, seven of whom were under 15.[38]

A 19-year-old student told Human Rights Watch that, one day, she was met by M23 soldiers as she arrived at school: “They stopped three of us students, and the others fled. They gave us bundles of wood which we transported 10 kilometers, until they found other people to stop and take the [load] we had.”[39]

A parent explained how his village tried to protect students at their school:

There were rumors that the [M23] were preparing an attack on the school so that they could get the children for military service. So we got together, all of the parents, and put in place a security alert system where we left two parents outside the school and two others along the road from where the fighters came. As soon as one of those who went to check on the movement of [Ntaganda’s forces] saw fighters coming our way, they would run to alert us, and we would go straight to the school director and tell him to let the children go.... We were driven to this when we learned that students had been taken in a school in Kasebaya, a town 20 kilometers from here.[40]

Recruitment of Children from Schools by Other Armed Groups

Other armed groups in eastern Congo have also recruited children in schools or while children are walking to or from school. Many were then sent to fight on the battlefield with little to no training. Others served as porters or cooks, and many of the girls were forced to be sex slaves.

FDLR combatants have forcibly recruited hundreds of children into their ranks, including FDLR dependents and Rwandan Hutu refugee boys, as well as Congolese children. MONUSCO child protection officers documented the recruitment by the FDLR of 136 boys and 1 girl, ages 9 to 17, predominantly in North Kivu, between January 1, 2012, and August 31, 2013. Of the recruits, 31 were 15 years old, 23 were 14 years old, and 26 were age 13 or younger.[41]

Most of the children were abducted during FDLR attacks on their villages. After being forced to transport looted goods to the FDLR’s camp, they were told to stay with the FDLR. Others were abducted on their way to the market, in the market, on their way home from school, or while working in the field. Some were family members of FDLR combatants. During an intensive abduction campaign in the Mpati area in Masisi territory, in February 2013, teachers and students were recruited from schools to fight.

A former FDLR fighter told Human Rights Watch how the FDLR attacked the Bumbasha Institute, a secondary school in Rutshuru, in July 2013, kidnapping ten boys and three girls, as well as two other girls from the village. They forced all of the children to join the FDLR and serve as combatants or forced laborers.[42]

APCLS fighters have also forcibly recruited children into their ranks. A 14-year-old boy was captured by APCLS fighters on his way home from school with four other boys, ages 12 to 14. After escaping from the group in 2014, he told Human Rights Watch:

The life we led was very difficult because we spent nights without eating. They told us that’s what it is to be a soldier. We should be different from civilians. During these times, they gave us strong drinks like King Whiskey and Simba —all that in order to differentiate us from civilians and make us have self-control. They also beat us and that was part of the training. They dragged us through the mud like pigs.[43]

A UN report also documented the new recruitment of 185 boys and 5 girls by Nyatura groups between January 1, 2012, and August 31, 2013, including 34 children under 15 years old. The report noted that most of the children were recruited on the road to the market, in the market, on their way home from school, in school, while farming, or walking to their fields.[44]

Rape and Other Sexual Violence against Girls

Sometimes, soldiers and fighters target girls from schools for abduction and sexual violence. After being raped, girls often drop out of school because of the associated stigma, medical consequences, or because they are scared of being attacked again.

A female teacher from Rutshuru territory, which was under the control of the M23 at the time, told Human Rights Watch:

Sometimes, fighters come to the school to find girl students. We [teachers] can’t refuse. They [the girl students] go with [the fighters]. Often, students arrive late to school, because they get caught en route…. Soldiers don’t come into the classroom, but when a fighter knocks on the door, you have to answer. This happened in May. I said, ‘Hello.’ He asked for a girl. I can’t refuse. So I called the girl, the one that he named, and she went with him. He didn’t have a gun, but his escorts were behind him, and they had guns, three of them. [The fighters] know [the students] names from encountering them on the road. It would happen three to four times a month [at my school]. It would be lots of girls, maybe 10 a month or so. I can’t really say. We can’t say anything; if we do, we could be killed.[45]

Camille, who was 16 when Human Rights Watch interviewed her, said she had dropped out of secondary school in the Lukweti area without finishing her exams after she was raped by an army soldier and became pregnant. “They got us when we were fleeing but still in the school enclosure,” she told Human Rights Watch. “It was government soldiers who took us. They took us two girls and raped us.”[46]

A student in Nyongera explained to Human Rights Watch some of the difficulties girls at her school faced during the time that the M23 controlled the area:

There was a military barrier right beside our school…. Some fighters stood at the gate. If they saw you coming into school, one would stop you and tell you to join him at recess [and threaten that if you did not] you will have trouble passing that way when you return at the end the day. Under these conditions, many of my friends dropped out [of school]. These same soldiers sent boys to pick up girls who they studied with, and if the boys didn’t do it, they’d be in danger.[47]

When Mai Mai Sheka fighters occupied the town of Pinga in 2012 and 2013, Human Rights Watch documented the rapes of at least 25 girls between the ages of 13 and 17 by Sheka fighters. Sixteen of the girls became pregnant, including a 13-year-old girl. Many of the girls dropped out of school because of their pregnancies.[48]

Other Violent Attacks on Schools, Teachers, and Students

Human Rights Watch has documented numerous cases in which schools, teachers, and students were targeted during attacks by armed groups on villages in eastern Congo.

On July 26, 2012, for example, M23 fighters forced a primary school teacher from Gisiza locality to transport boxes of ammunition from Kabaya to the Rumangabo military camp. When the teacher tried to return home, he was shot in the back by M23 fighters.[49]

On October 26, 2013, the Raia Mutomboki attacked the villages of Nkokwe, Muhande, and Kavere in the Mupfuni/Kibabi groupement in Masisi territory. Near the village of Kavere, they killed the Hutu director of a primary school. A witness who was hiding nearby in a cornfield told Human Rights Watch:

[The school director] was carrying a child on his shoulders when he met a group of Raia Mutomboki combatants who stopped him, just a few meters from where I was hiding. They said to him suddenly: ‘We are going to kill you.’ He responded by saying he was just a civilian and the director of a school. Another Raia Mutomboki fighter came and asked them: ‘What are you waiting for to kill this director? Don’t you see that he’s in good health? Kill him.’

They shot him in the shoulders from behind and he fell to the ground. After a few seconds, they stomped on his body with their boots and cut him with their machetes on his neck and arms. They stabbed the child in the knee with their Singer [bayonet]. There were seven combatants. I went and got the injured child after they left.[50]

The director of a school in the Ufamandu area, Masisi territory, told Human Rights Watch what he found when he came to inspect his school following an attack on his village by the FDLR in May 2012:

It was like we were in the bush because there was nothing there. We called the teachers together to see what we could do. It [the school] was just burned. There was nothing there. There was really nothing there.[51]

The director explained that they had lost the entire original school, which had been built of wood and tin, in the attack. They also lost all the school’s furniture, books, and documents. He explained that the students now studied in a rudimentary temporary structure that the parents built: “We put up tree sticks and a tarpaulin and we put straw as a roof.” A year after the attack, the school had still not been able to replace lost books.[52]

Soldiers loyal to Bosco Ntaganda took over a school in Kamurotsa on April 21, 2012, occupying all of the classrooms, the playground, and the school fields. The school administrator said that when he visited the school one day, he found soldiers grilling sweet potatoes inside one classroom, and using the desks as firewood:

I wanted to ask them why they were in the classrooms. [They responded by] intimidating me, and one of the soldiers forcibly took the bag I was carrying with me, and took money equivalent to US$150 that I had with me to pay the examination center for my students. Then they beat me up and told me to chew on a skull that was used as a teaching prop in a classroom of my school, which they thought belonged to a person that we had previously killed and then dug up and put in the class.[53]

A member of a school parent committee in Pinga told Human Rights Watch about an attack on August 28, 2013, by Mai Mai Sheka fighters: “I found the school and the office was destroyed. School desks were thrown in the stream. It was sabotage and they forced people to flee by destroying the school.”[54]

A teacher at an eight-classroom school, built by a small community in 2010 in the Ufamandu area of Masisi, saw fighters of a local armed group loot the newly-bought tin roofs from the school. “They took all the tin,” he told Human Rights Watch.[55] “We saw them take the tin toward Katoyi and Kahunda [presumably to resell]. It was a big operation. Everything else was burned.” The teacher estimated that many sheets of tin roofing were stolen, explaining that community members had bought the tin sheeting for the school in Ngungu, a town more than a day’s walk away, at $10 per sheet.

III. Military Use of Schools

I don’t know why the soldiers were in the school. There were a lot but I couldn’t count. I thought they were going to kill us all there.

—Lubuto B., 12, Kalungu, June 2013

The use of schools for military purposes, along with looting from schools, are the most frequently reported disruption caused by troops against schools in eastern Congo.[56] Government soldiers and members of armed groups have used schools as lodging and military positions and looted them for firewood and other resources.

When soldiers impose themselves into schools it puts students and teachers unnecessarily at risk and hinders students’ ability to learn. It also causes damage to school buildings, equipment, and teaching materials. In most cases documented by Human Rights Watch, school occupations lasted from two nights to a week or slightly more, although use for many months was also documented. Even brief military use left schools unfit for educational use without major rehabilitation.

In some cases, soldiers or fighters occupied schools entirely, forcing schools to close for the duration of the occupation. In others, they used schools after school hours and at night, leaving the school to partially function during the day, or they only used part of the school, with students attempting to continue their studies alongside the combatants.

Attempts to quantify the number of schools across Congo affected by military use between 2012 and 2014 is complicated by competing standards of verification and reporting used by different UN agencies and nongovernmental organizations, as well as difficulties in surveying schools due to factors such as insecurity and remoteness of locations.

For example, according to information published by the UN Secretary-General, the UN formally verified military use of 11 schools by the Congolese army and 1 school by the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (Forces démocratiques pour la libération du Rwanda, FDLR) in 2012; 25 incidents during 2013, including 13 cases by the Congolese army; and during 2014, 12 schools were used, including at least 4 by the Congolese army and 6 by the Raia Mutomboki.[57] However, an investigation by the UN Joint Human Rights Office (UNJHRO) received reports of at least 42 schools occupied in the area of Minova and neighboring Bweremana in November 2012 alone.[58]

Groups Using Schools for Military Purposes

Human Rights Watch documented schools being used for military purposes by the Congolese army, the M23, the FDLR, Nyatura groups, and the Raia Mutomboki.

Sometimes schools have been used multiple times by different groups. The director of one school told Human Rights Watch:

On May 10, 2013, we stopped school activities as the school was occupied by [Congolese army] soldiers who were in combat with the M23…. [Congolese army] soldiers stayed for a month in the classrooms.… The school was transformed into a military camp…. [Then] the M23 … managed to chase away the [Congolese army] from the area. They fled, leaving behind some military equipment in our school that the M23 recovered upon their arrival. The M23 then, in turn, also used our school for a period. And when, during the months of October and November 2013, the fighting resumed between the [Congolese army] and the M23, the [Congolese] military chased away the M23 and reoccupied the classrooms of our primary school.[59]

The prefect of a secondary school in an area caught in intense fighting between the Congolese army and the M23 in Rutshuru territory in early 2013 lamented the similarity of abuses and damage by all sides: “When government soldiers come, they interfere with my school. When M23 fighters come, they interfere with my school.”[60]

Several other school officials told Human Rights Watch their schools were occupied successively by Congolese army soldiers and members of armed groups, with similar resulting damage to their school buildings and equipment. Data from UNICEF and reports by Congolese nongovernmental organizations suggest that scores of schools in eastern Congo were occupied by more than one armed force in 2012 and 2013.[61]

Use of Schools as Military Bases and Temporary Accommodation

School staff described how soldiers and fighters demanded entry into classrooms or broke the locks off doors in order to enter schools and use them as bases or for temporary accommodation.

A secondary school director explained what happened when the Congolese army arrived in May 2012:

They [army soldiers] put their weapons and ammunition in the classrooms…. The students were afraid and said that the [army] would start fighting soon. Some fled. The captain told me to calm the students; that they would win soon…. We were cohabitating in the school with the [Congolese army] who were staying during the night. It was for about 10 days.[62]

When the M23 took control of Goma in November 2012, soldiers from several army units based nearby retreated to the area around Minova, a town 50 kilometers away. Over the next two weeks, army soldiers from North and South Kivu occupied at least 42 schools in the area of Minova and neighboring Bweremana, preventing over 1,100 children from having access to their schools, according to an investigation by the UN Joint Human Rights Office (UNJHRO).[63]

The director of one affected primary school told Human Rights Watch how soldiers arrived during the night. “They made me come from my house to the school in order to open the classrooms,” he said. “The soldiers said, ‘Open the classrooms because we must stay here. You see that there is a war.’”

School officials and teachers often said they felt powerless to protect their schools from occupation. Espérance L., the deputy director of a primary school in Kalehe territory, told Human Rights Watch that, one day in March 2013, she was alone at the school finishing up paperwork when she saw combatants of the Nyatura armed group in the school courtyard. Fearing they may hurt her, she slipped out a door and escaped. Returning the next morning with the school’s director and several students, Espérance described seeing fighters and their wives cooking in classrooms:

Without any authority, they entered the classrooms, and used the school desks for firewood…. They made makeshift beds…. I asked a soldier, ‘Why are you here?’ [He responded,] ‘We saw good things here. We’re en route to a training. ‘I asked why they were traveling with their families. [He responded,] ‘We go with our wives because they search for food for us. The wife of a soldier is also a soldier.’[64]

The school had to close while the Nyatura combatants stayed there for two nights, leaving behind smoldering fire pits and emptied classrooms.

Teachers and school directors told Human Rights Watch that government soldiers often dismissed their concerns about protecting the schools, claiming that wartime circumstances justified the school’s occupation. The director of a primary school in Nyiragongo territory, north of Goma, told Human Rights Watch what happened after army troops occupied his school in September 2012: “We tried to organize a meeting with the [Congolese army], but they refused and said that we were in wartime, and they weren’t willing to give the time.”[65]

Duration of Military Use

In numerous instances, armed groups and the Congolese army have used schools as temporary accommodation while traveling to or from military operations, sometimes far from active combat zones. For example, at a school in Masisi territory, army soldiers occupied classrooms overnight in February 2013 while traveling south. The school’s deputy director said that he had asked them, “‘Why are you occupying the school?’ They said they wouldn’t stay long. It looked like they were just passing through. They stayed only at night, outside of school hours. Some of them wrote on the doors, ‘Don’t enter, this is my room.’”[66]

But in some cases, occupations lasted for days, weeks, and even months. A teacher at a primary school in Nyiragongo territory described how soldiers used his school as a small command center for several weeks in September and October 2012: “The [Congolese army] stayed at the school at night…. They were in some of the rooms. Then they would leave during the day. Later, in the afternoon, the soldiers reoccupied the rooms.”[67]

The dozens of schools taken over by army soldiers in Minova around November 20, 2012, began to be vacated after December 24. In one school, however, Kashenda primary school, located approximately 5 kilometers from Bweremana, soldiers continued for at least eight more months to park military trucks in the school courtyard. Two military trucks were parked on the premises during Human Rights Watch visits to the school in June and July 2013.[68] Several soldiers guarded the trucks and military equipment, and witnesses reported that they used the school’s toilets.[69] A low-ranking soldier present at the school in June 2013 told Human Rights Watch that the soldiers were positioned there “to secure the school.”[70]

Use of Schools for Military Training

Schools have also been used as places to train soldiers and forced recruits. For example, a man who was abducted by the M23 told Human Rights Watch that he was taken first to a classroom of the primary school in Chengerero and then to a former kindergarten for military training for a week in June 2013.[71] And at Institut Bweremana, immediately next to the army’s headquarters in Minova, soldiers frequently used the school grounds from November 2012 until at least July 2013 to conduct parades and military training exercises.[72]

Held Captive in the ClassroomAmani, a 10-year-old primary school student from the Minova area of South Kivu, was surprised to see soldiers approach his school while he and other students were preparing to leave for the day. Congolese army troops fleeing a rebel advance on the city of Goma had occupied dozens of schools in nearby Minova and Bweremana, but his school was up on the hill and had not yet been occupied. Just before 1 p.m. on November 24, 2012, soldiers arrived at Amani’s school. Fearing what the soldiers might do to them, students and teachers ran in every direction. But Amani and several other students did not make it past the school courtyard. As they began to occupy the classrooms to use as temporary lodging, the soldiers rounded up Amani and at least five other students and forced them to help with various tasks.[73] Amani and his fellow students were told to fetch water, steal food from nearby farms, and prepare fires for cooking. “They destroyed the school desks,” Amani said.[74] “I had to help cut up the desks for firewood,” he continued, and, waving his hands to explain how a piece of wood flew toward his face, he showed how he got a scar on the bridge of his nose. “They told us we had to work for them. They brought us into the school and beat us.” Soldiers beat Amani and several other students. When another student, Muhima, 14, refused to work for them, a soldier cut his arm: “I had to pay to get it stitched up at the health clinic,” he said.[75] Fimi and Vandah, two 16-year-old girls who were held at the school at the same time as Amani, reported how they and other girls in the area were harassed by soldiers. “If you resisted, they would rip your clothes,” Fimi said.[76] The soldiers held Amani for six days at the school. He and other students explained to Human Rights Watch how they were not allowed to return home or see their parents.[77] “We slept in the classroom,” Jean, 14, another student, explained to Human Rights Watch. “There were soldiers in front of us and behind in the same classroom to prevent us from escaping. When we resisted, they said, ‘We will shoot you.’”[78] Parents of two students told Human Rights Watch that they briefly saw their children from afar, but they felt powerless to remove them from the situation.[79] When the soldiers finally left, they forced Jean and other older students to help them carry their heavy supplies several kilometers away. Amani was then allowed to return home. There, his parents asked if the soldiers had beaten him. “I said, ‘Yes.’ They said, ‘Understand, child, life is like that.’” |

Negative Consequences of Military Use of Schools

Almost inevitably, use of schools by the government armed forces or armed groups harms students’ safety or education. When students mix with soldiers, they are often subjected to abuses such as forced recruitment, forced labor, beatings, and sexual violence.[80]

Whatever the duration of the occupation, in every instance of the military use of schools documented by Human Rights Watch, witnesses described how forces looted the school’s equipment or building materials to use as firewood or for other purposes. When schools are damaged or destroyed, and school materials looted or burned, education infrastructure vital to the realization of children’s right to education is lost.

Girls’ Experiences, Fear of Rape and Sexual Abuse

When students are forced to share their school premises with soldiers, or are present when soldiers take over a school, the students, and in particular girls, are at risk of rape and other sexual assault, as described in the previous chapter. Fear of such abuse also causes girls to drop out of school preemptively. “Most girls quit school when we were occupied,” said an official whose school has been occupied by both the Congolese army and M23.[81]

Forced Labor

Fighters using schools for military purposes have forced students, teachers, and other local residents to work to establish a military camp. A village leader said that forces loyal to Bosco Ntaganda forced him to get people from his village to help dig trenches around the school they were using. “Others were taken by force to dig holes and fetch water,” he told Human Rights Watch.[82]

Children or teachers can also be forced to carry out work unconnected with the school. A prefect whose school was used by M23 forces told Human Rights Watch, “Often, the M23 asks the teachers to help them find water, cut a tree, do random tasks. I ask the professors to justify their absences, and they tell me how they are taken to help construct M23 camps.”[83]

Schools Damaged or Destroyed by Occupying Soldiers

Forces occupying schools have regularly taken tin roof sheeting for shelter; used school benches, the wood sidings of classrooms, and textbooks and notebooks to light and burn fires; and raided the supplies of school canteens. The theft of school property may constitute the unlawful seizure of non-military property, or looting.[84] Because local communities frequently fund the construction of their schools in eastern Congo, the destruction and damage of schools hurts the community financially.

In one village, M23 fighters occupying the primary school and secondary school during July 2013 removed doors and windows and sold them, according to school officials.[85]

A teacher at a school in the Ufamandu area of southern Masisi territory described the behavior of a mixed group of army soldiers and Nyatura combatants in August 2012:

All the office equipment was stolen. We saw some manuals that were burned and some administrative documents. Some documents were also taken. Now the office is empty. We are starting from zero.[86]

A school official listed the damage to his school, which was taken over by soldiers loyal to Bosco Ntaganda in April 2012:

The administrative and educational offices were completely destroyed and looted. All the documents were burned or thrown out and scattered across the courtyard. Desks and some piece of wood siding from the classrooms were burned as firewood. The windows of the new building, which had recently been rehabilitated, were broken. The metal roof had holes in it caused by [bullets] or shrapnel. The water tank …was removed and completely broken. Chairs, office tables, and desks were broken. The flag of the school was burned.… All doors to classrooms were demolished. All training materials were taken away from the school. And this list is not exhaustive.[87]

A teacher at a primary school in Nyiragongo territory, just north of Goma, described how soldiers used his school as a small command center for several weeks in September and October 2012:

There were normally about seven soldiers who stayed in my classroom. When I arrived in the mornings, I counted them…. They were responsible for damaging books and demolishing the school’s canteen and some of the floor tiles. No one was controlling them…. We had to bear these problems. And the students had to continue to study. There wasn’t another way to go about it.[88]

A village leader explained what M23 fighters did to a school in his village:

They destroyed a block of classrooms built out of wood siding, which they used as firewood. And the chief military commander who was there who I recognized, Baudouin Ngaruye, spent the night in the prefect’s office. They had forced the door open, and all the papers were scattered in the office and in the playground. They used some of the papers and documents in the office to lie on as a mattress.[89]

Another school official described the damage caused by Nyatura fighters and their wives who occupied the school: “They broke most of our materials. They damaged the blackboards.”[90]

“They were like bandits,” the guard of a secondary school in the Minova area said, describing how army troops arrived after school hours, intimidated him, broke the locks on classroom doors, and occupied his school.[91]

When fighters occupy schools with their families it places additional strain on school infrastructure. In September 2012, government soldiers and their families occupied eight classrooms and the grounds of the secondary school where Ezechiel N. served as director in Rutshuru territory. “Their children defecated in the school courtyard, which the schoolchildren use for recreation, and their wives cooked there. They took school bricks to position their saucepans for cooking,” said Ezechiel.[92]

Schools Damaged or Destroyed by Attacks Because of Military Presence

A number of schools came under attack because of the presence of the army or armed groups in the school. Such attacks are legitimate under the laws of war, yet nonetheless result in damage to education infrastructure and thus impinge on students’ studies.

One director explained that while his primary school was used by Congolese army soldiers, they installed heavy weapons that were used to fire on the M23 forces on a hill about five kilometers away. In return, the M23 fired in the school’s direction. “One classroom was completely destroyed after a bomb fell on it from the M23 area,” he said.[93]

During fighting between People’s Alliance for a Free and Sovereign Congo (Alliance du peuple pour un Congo libre et souverain, APCLS) and the army in early and mid-2012, government soldiers occupied several schools in Masisi territory. One director explained how government troops used his school four times from March to June 2012: “The school was just grounds for them. They stayed there. Our military are not there to protect but to use firearms and damage things.” The director noted that “there were spent shells everywhere and in the school courtyard,”[94] indicating that weapons had been fired inside the school.

Ongoing Dangers After School Use

The risk to students and teachers’ safety may not end even once the troops have vacated a school.

A village leader explained that after the M23 abandoned his village’s school, a demining organization found “rocket-like bombs” around the school, one in each of the four corners of the school plot, and a fifth at the entrance to the main road leading to the school, about 100 meters from the school.[95]

During a visit to Institut Bweremana in Minova in June 2013, Human Rights Watch observed technicians removing large munitions from the school latrines. Found in the latrines were nine 107mm rockets, two boxes of standard AK-47 ammunition, and two recoilless rockets.

Though the latrines had been closed and partially destroyed so as to prevent their use, Human Rights Watch observed children playing around them. New latrines had been built about 50 meters away, but removing the munitions took more than seven months.

Harm to Education

The presence of troops inside schools can lead to children being forcibly excluded from school, or to students avoiding school due to concerns about their own safety. An Education Ministry official in North Kivu said, “In wartime, soldiers with no sense of patriotism occupy the school space and force schools to move their students.”[96]

Deterioration of a school’s physical structure and a loss of education materials have also hurt students’ studies. Given the dire state of many Congolese school buildings, even moderate damage can render them completely unusable. The director of a Congolese NGO in South Kivu that focuses on education explained: “The schools start in such a state of disrepair. They are not constructed well. So you take away a piece and the school disappears.”[97] Accordingly, teachers and school directors often told Human Rights Watch that the damage inflicted on their schools by troops constituted “the destruction” of their school.

One parent explained why students did not want to return to his child’s school after an attack on his village by Nyatura forces:

I went to the school. Everything was ruined in a way that you couldn’t repair it. They broke the planks [of the walls] with machetes. They ruined the [tin] roof sheeting in each class. There were six classrooms.... They are no longer usable. After the war, the students didn’t have the desire to study because the school was destroyed.[98]

A primary school director said:

The consequences of the invasion of our school by armed groups and army soldiers included the loss of students, lower attainment by students because teachers lack textbooks … the parents’ insolvency due to poverty caused by the war, and when it rains during school hours, we have to send students back home for fear they will get wet because the roof leaks [due to holes caused by shrapnel damage].[99]

Another parent talked about the consequences of losing school desks: “Some of our students write on their knees. But they get tired. When they get tired, they stop writing.”[100]

Use of Schools for Extortion and Illegal “Tax” Collection

In some areas under the control of armed groups, fighters used schools to collect illegal “taxes” or to ensure that students had paid such taxes. Illegal taxation constitutes an important source of revenue for armed groups, and is generally imposed on all of the population. The targeting of schools and teachers at school to enforce the tax leads to additional safety issues at schools and interferes with children’s education.

In June 2013, combatants from a Nyatura group gathered all 20 of the teachers at a primary school in Bushanga village, Masisi territory, and forced them to pay 1,200 francs [$1.30] each.[101] Male students, aged 15 and up, were also forced to pay.[102]

A community leader and parent from the Mpati area in Masisi territory told Human Rights Watch:

The school is closed because of bandits coming and beating students. They also beat the teachers. They enter the classrooms with their guns. And when that happens, everyone flees…. One day, they came into the class and asked all the students to show their [receipt showing they had paid the illegal tax]… Some students fled and got me, and I went to the school. I asked them why they were in the school. [They replied:] ‘It’s not your problem. We are in control here.’[103]

A 16-year-old boy from the Mpati area said he was briefly detained by Nyatura fighters when his parents were unable to pay the armed group’s “tax.” The director of his school went to negotiate the boy’s freedom. Afterwards, the boy said, “The director warned me that if I came back to school, they might take me again and take me away even further, to where he couldn’t rescue me. So that’s why I stopped going to school.”[104]

A teacher from Masisi territory shared what happened after teachers refused to pay an informal tax to Nyatura fighters:

On April 22 and 23, 2013, the situation worsened in the classrooms when a fighter … entered with his weapon and made us exit the classrooms. We weren’t able to manage this situation so we decided to suspend school activities for 10 days, because we didn’t have the money.[105]

IV. International Examples of Good Military Practice Protecting Schools

Not all uses of schools for military purposes are prohibited by the laws of armed conflict. However, unlawful and unnecessary misuse of schools is made more likely by a lack of clear regulations, training for soldiers on how schools should be protected from military use, and adequate logistical support.