“No Money, No Justice”

Police Corruption, Abuse and Injustice in Liberia

Glossary of Abbreviations

AFL: Armed Forces of Liberia

CPA: Comprehensive Peace Agreement

CDC: Congress for Democratic Change

ERU: Emergency Response Unit

FRTUL: Federation of Road Transport Union of Liberia

GAC: General Auditing Commission

INCHR: Independent National Commission on Human Rights

LACC: Liberia Anti-Corruption Commission

LD: Liberian Dollar (colloquial)

LISGIS: Liberia Institute of Statistics and Geo-Information Services

LMTU: Liberia Motorcycle Transit Union

LNP: Liberia National Police

NGO: Nongovernmental Organization

PSU: Police Support Unit

PRS: Poverty Reduction Strategy

PSD: Professional Standards Division

UNMIL: United Nations Mission in Liberia

UNPOL: United Nations Police

Map of Liberia

© 2013 Human Rights Watch

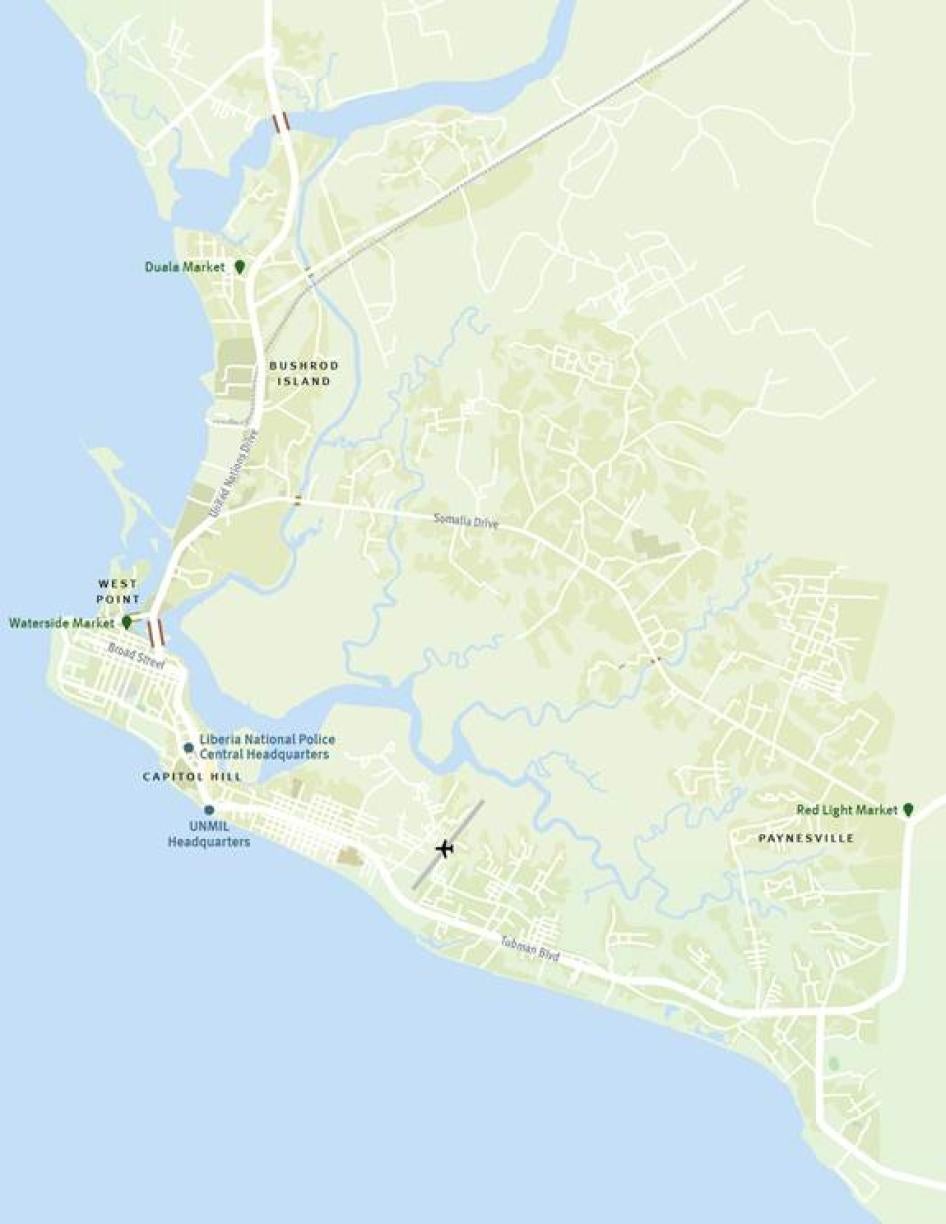

Map of Monrovia

© 2013 John Emerson/Human Rights Watch

Summary

I went to the police investigation department with a complaint [about how I was arrested, jailed for five days, and told to pay money to be released]. The whole thing was like a trick. They kept saying tomorrow, tomorrow [they would address my complaint]. The culture of impunity [in the police] continues to exist.

—Joseph (pseudonym), 43, victim of police corruption and abuse, Monrovia, December 2012

Sometimes you go to work and do your own thing.… Everyone is doing the same thing [with corruption]. This is happening and UNMIL [United Nations Mission in Liberia] is here. What do you think will happen when UNMIL leaves? It will be worse.

—Police chief inspector, Monrovia, January 2013

From 1989 to 2003, Liberia was engulfed in two civil wars that killed more than 200,000 people and displaced another one million. The West African country, now headed by Africa’s first elected woman president, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, is politically stable and rebuilding, assisted by numerous international donors and institutions. The United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) has extensively supported Liberia since the signing of the 2003 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) in Accra, Ghana, and has maintained a strong presence in the country.

Since early 2013, UNMIL has begun to draw down its peacekeeping forces—which currently number around 8,000 uniformed personnel—with the goal of more than halving its presence by 2015. Increasingly, maintaining law and order will be under the sole stewardship of Liberia’s government and its security forces.

The government has emphasized the importance of the security sector, specifically the police, in post-war human rights compliance and human development. Its two major development plans—the Poverty Reduction Strategy (PRS) and Liberia Rising/Vision 2030—stress the importance of a professionalized security sector in securing human rights and access to justice.

The Liberia National Police (LNP), which stands at 4,417 police officers, is now twice the size of the army and bears the primary responsibility for maintaining law and order and creating the stability required for Liberia’s post-conflict economic prosperity. UNMIL has estimated that Liberia will need 8,000 officers, or nearly double the current LNP force, to adequately serve the Liberian public upon the UN’s departure, although the UN Secretary-General’s report on Liberia suggested that improving the quality of officers, not the quantity, should be the priority. This idea is supported by several special inquiries called for by President Sirleaf to investigate widely publicized instances of police misconduct.

The police’s professionalization and its ability to promote human rights and the rule of law in the wake of UNMIL’s departure are crucial for Liberia’s economic development and long-term stability. As Liberian lawyer and activist Tiawan Gongloe told Human Rights Watch in November 2012, “It will be the quality of governance that will sustain the peace when UNMIL leaves.”

But Human Rights Watch’s research in Liberia found that the ability of the police to enforce the law and investigate wrongdoing is severely compromised by lawlessness and abuse that police officers themselves inflict on ordinary Liberians, especially those living on the margins. The police force is riddled with corruption and a lack of professionalism and accountability. A 2012 survey showed that Liberians perceived the police to be the most corrupt institution in Liberia; the courts were a close second. Even more recently, a Transparency International report, Global Corruption Barometer 2013, noted that the police were perceived to be the most corrupt institution in the country.

From November 2012 to February 2013, Human Rights Watch interviewed over 220 people about police abuses and the policing challenges. We spoke with more than 120 victims of police corruption and over 35 police officers from Montserrado, Bong, Lofa, and Grand Gedeh counties. Researchers conducted interviews primarily in urban areas, but also in rural locales throughout the country.

Regardless of location, victims of police corruption frequently expressed their concern that in Liberia, “justice is not for the poor,” or “no money, no justice.” They described police extortion at every stage of a case investigation—from registration of a complaint to transportation to the crime scene, to release from police detention. This institutional neglect has created the credible perception among many Liberians that wealth, not guilt, determines the outcome of a criminal case.

All too often, our research found, the police act as predators, violating the law, rather than protecting the population. Human Rights Watch documented numerous cases where police officers entered poor communities at night or simply patrolled a street and engaged in shakedowns. In these situations, officers approached or followed local residents and under the pretext of searching them for contraband items or weapons, demanded money, sometimes using threats or violence. Motorcycle taxis, street vendors, and taxi drivers are particularly vulnerable to extortion and theft by the police.

Liberian police officers themselves face numerous challenges in performing their jobs. They frequently lack the basic but essential tools of policing, such as vehicles or the fuel for them, and even pens and paper for reports. Patrol officers say that their wage—currently US$135 per month—does not reflect the long hours they work and is insufficient for meeting their basic needs. This encourages the police to support themselves and their families through extortion and bribe-taking.

Commanding officers also place pressure on their subordinates to make payments up the chain of command. Officers commonly pay their supervisors to obtain promotions, desirable posts, and other perquisites—or just to avoid negative assignments.

To raise the necessary cash, police often “hustle” for money on the street—going after motorcycle taxis or street vendors—instead of reporting to their posts. Thus two kinds of harm are inflicted: on those people who are compelled to pay the bribes, and the general public, which then goes without another police officer. Commanders often give up on trying to suspend or remove derelict officers since their depot, or police station, might not receive replacement officers.

There has been some progress in professionalizing the LNP since the end of the war. Arrests are now conducted more professionally, with broader recognition by the police that they need to either charge or release a suspect within 48 hours. Torture and ill-treatment in detention, long a problem in Liberia, has decreased significantly, largely due to UN monitoring and trainings. Some officers are also now more inclined to report the abusive behavior of others, which is partly an accomplishment of the Professional Standards Division (PSD), the internal monitoring arm of the LNP.

Despite these positive developments, corrupt practices persist throughout the country. The LNP has said that it is trying to address its internal culture and encourage accountability. However, success in bringing cases against LNP officers has been limited. A number of people who had tried to report their case to either a commander or the Professional Standards Division told Human Rights Watch that their complaints went unaddressed. Many other victims of police abuses said that they were either too afraid to report the violation, or, because of negative past experiences with pursuing police accountability, would no longer report cases to LNP personnel.

These and other obstacles raise questions about the capacity of the LNP to fully address corruption within its ranks at all levels, pursue cases against high-level officials, set an example of probity for more junior officers, and ensure all police act professionally and in accordance with human rights.

UNMIL itself has flagged poor police conduct as a potential impediment to safeguarding peace and security in Liberia. In a 2012 report, the UN reached what it called a “sobering” assessment of the LNP’s policing capacity, and expressed concern about the extensive logistics deficiencies and unprofessional behavior of many officers. The report also noted that while the development of security institutions had received considerable attention, there had been less of a focus on governance and accountability mechanisms for these institutions, which remain weak. Notably, the lack of democratic oversight of security agencies contributed to the corruption and abuse that were endemic under previous regimes in Liberia.

Rampant police corruption compromises the rule of law in Liberia and violates the rights of ordinary Liberians. Police harassment and extortion result in threats to life, liberty, and the security of the person. It also denies the poor equal protection of the law and hinders their ability to provide for their families, obtain an education and health care, and reap the benefits of Liberia’s much-needed economic development. The Liberian government has made important progress in the political and economic spheres since the civil war ended 10 years ago. Reining in the police, upholding basic rights, and restoring trust in the security sector is essential for continuing these gains and ensuring their longevity and durability.

UNMIL and donor governments should assist in this effort through helping the Liberian government evaluate and review the needs of the LNP, strengthen anti-corruption institutions, and ensure that foreign assistance for the security sector is meticulously tracked.

Recommendations

To the Government of Liberia

- Call on the legislature to enact a comprehensive anti-corruption law after input from civil society groups, the Liberia Anti-Corruption Commission, and legal experts.

- The president should act on her pledge to establish an independent Civilian Oversight Board for the Liberia National Police that would accept complaints from the public on acts of police misconduct.

- Publicly support investigations and prosecutions by the Ministry of Justice and the Liberia Anti-Corruption Commission of high-level corruption at the LNP.

- Urge the Senate to promptly hold hearings into irregularities in past General Auditing Commission (GAC) reports.

- Ensure that Lift Liberia/Liberia Rising/Vision 2030 addresses security sector reform, especially professionalization of the police.

To the LNP: Transparency and Strengthening Oversight

- Implement an anti-corruption strategy based on input from members of the police and civil society, and make that strategy public.

- Work with UNMIL and other international partners to promptly complete the new Police Act, which should address recruitment and training protocols, appropriate labor limits (such as maximum hours per week), and measures to address absenteeism.

- Work with international partners to institute a tracking system for all logistics, including fuel, vehicles and vehicle repairs, and supplies. Use the tracking system to report concrete numbers on logistics shortages to the Liberian government for consideration in the budget process.

- Reinstitute the use of the promotions board and task the Professional Standards Division with monitoring promotions to ensure that they are based on a clearly defined merit system.

- Hold commanders responsible for the foreseeable or repeated misbehavior of the officers under their command.

- Institute transparent investigations and adopt disciplinary measures, including referring cases for prosecution, of the commanding officers of patrol officers who engage in extortion, threats and other illegal acts, or who prevent members of the public from bringing complaints of police misbehavior.

- Officers subject to investigations should be suspended without pay, pending findings.

To the LNP: Professional Standards Division

- Ensure via the LNP leadership that high-ranking officers do not intervene in disciplinary measures against subordinates.

- The PSD’s Public Complaints section should make public the number of complaints it receives annually, the number of complaints it deems to be valid, the number of investigations that it undertakes, and the results of those investigations.

- The PSD’s Inspection and Control unit should publish the number of inspections it conducts annually, and the results of those inspections.

- Adopt measures to improve the ability of the regional hub system to receive and respond to public complaints originating from outside Monrovia.

- Conduct trainings with the PSD to make sure it professionally responds to all complaints and can resist efforts to interfere in its disciplinary processes.

To the LNP: Recruitment and Training

- Recruit more police officers from the counties who are willing to remain in their counties. Ensure that officers deployed to the counties have equal access to promotions and opportunities for training and advancement, similar to those officers assigned to Monrovia.

- Provide ongoing and appropriate human rights training.

To Independent Government Accountability Agencies

- The General Auditing Commission should complete and publicize an investigation into police corruption and abuse, including both budgetary irregularities and performance shortfalls.

- The Liberia Anti-Corruption Commission (LACC) should continue to investigate and prosecute high-level police corruption cases.

- The Independent National Commission on Human Rights should develop the capacity to investigate and take action on human rights complaints, in accordance with its mandate.

- The Independent National Commission on Human Rights should more actively investigate and document alleged human rights abuses, including those abuses involving the police, and publicize that information.

To the United Nations and Donor Governments

- UNMIL should assist in the establishment and implementation of a logistics tracking systems for fuel, vehicles and vehicle maintenance, and supplies.

- Donor governments should require tracking systems for all assistance to the LNP and provide adequate support for such tracking.

- The UN and donor governments should assist the LNP in compiling findings on logistics shortages.

- UNMIL should assist in regular procurement requests to ensure that logistics are arriving to their slated location.

- The UNMIL Human Rights and Protection Section and UNMIL should conduct human rights trainings for the police, with the support of donor governments.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted by Human Rights Watch between September 2012 and June 2013, including field visits to Liberia from November 2012 to February 2013. Research was conducted in four counties, including Montserrado, the county where the capital city, Monrovia, is located, Lofa in northern Liberia, Bong in central Liberia, and Grand Gedeh in eastern Liberia. We chose these locations based on geographic diversity, reports of abuse from the media and domestic nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and the location of reform efforts.

During a total of six weeks in Liberia, three Human Rights Watch researchers conducted interviews with over 220 individuals, including over 120 victims of alleged police corruption, 35 police officers, and numerous members of civil society organizations, government officials including the police inspector general, diplomats, and officers from the United Nations Mission in Liberia. Human Rights Watch requested a meeting with the minister of justice, Christiana Tah, by formal letter on January 29, 2013, and through multiple follow-up calls and emails; however, a meeting was not granted.

Interviewees were identified through NGOs, Liberian consultants, and professional associations. Police officers were identified through referrals and random stops at police stations. Interviews primarily took place in English. On a few occasions, a Liberian consultant assisted with translation from Liberian English. Interviews in Bong, Lofa, and Grand Gedeh counties were conducted individually, but often in the presence of others in open spaces in the work areas of the participants. No material compensation was given for the participation of the interviewees. Most interviews with victims in Monrovia took place individually at the offices of one of several NGOs. Human Rights Watch covered victims’ travel expenses, but victims received no compensation for their participation.

Interviews were conducted at the consent of the interviewees with the explanation and understanding that the information provided would be used in this report. All victims, non-senior police officers, and many officials participated on the basis that they would remain anonymous. As a result, where certain officials could easily be identified by the mention of their county, position, or rank, this information has been omitted.

Background

The central goal for the security sector is to create a secure and peaceful environment, both domestically and in the sub-region, that is conducive to sustainable, inclusive, and equitable growth and development.

—2008-2011 Liberia Poverty Reduction Strategy

From War to Reconstruction: Rebuilding Liberia and its Security Sector

In August 2003, shortly after the resignation and flight of President Charles Taylor, the Liberian government and two opposition armed groups signed the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) in Accra, Ghana, ending the country’s second civil war in 14-years. The country was in a state of political and economic collapse,[1] with no functioning justice system.[2]

Recognizing the need for an integrated approach to stabilize Liberia, the United Nations Security Council adopted a resolution in September 2003 that established the UN Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) and called for UN assistance to enforce the CPA and for UN participation in security sector reform, humanitarian assistance, and human rights monitoring.[3]

A key goal of the CPA was to reconstitute the highly abusive military and to reconstruct the police, the courts, and other parts of the security and justice systems that were corrupt, mismanaged, and rights-violating.[4] The United States government took charge of rebuilding the Armed Forces of Liberia (AFL), while the UN oversaw the recruitment and restructuring of the Liberia National Police (LNP).[5]

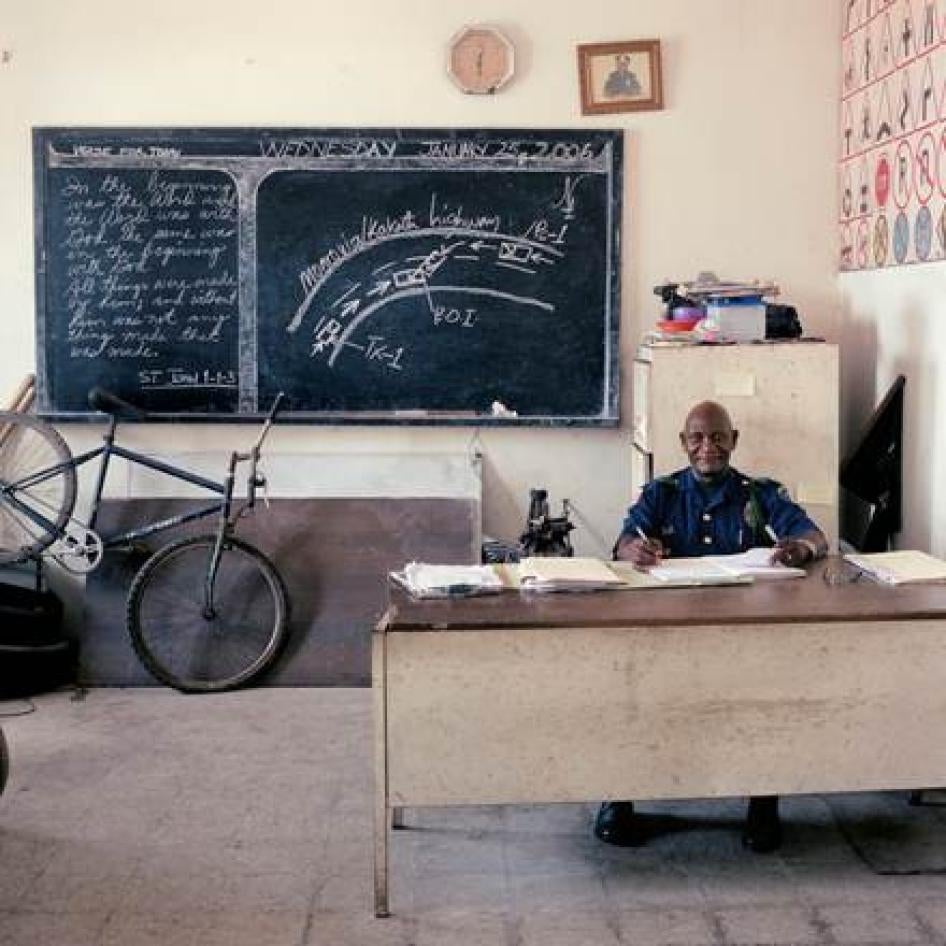

United Nations troops and the newly trained Liberian police force fan out in a neighborhood in Monrovia on September 14 2006, in an effort to quell increased crime in the city. © 2006 Reuters/Christopher Herwig

The United States completely demobilized the AFL in order to recruit, vet, and train an entirely new military, whereas the UN relied on a vetting procedure to identify which police officers could continue in the force and to select eligible new recruits. United Nations Police (UNPOL) faced a number of challenges in recruiting, vetting, and training the new LNP, which undermined its ability to effectively identify and weed out abusive and corrupt officers.[6]

Ten years after the war, Liberia has inadequate numbers of police officers, particularly outside the capital. As of February 1, 2013, there were only 4,417 police officers in the LNP, for a country of more than four million people.[7] In a 2006 global survey the UN found that the median number of police officers per 100,000 people was 300, and in Africa as a whole the median number was 187 officers per 100,000 people. Liberia has slightly over 100 officers for every 100,000 people, significantly lower than the global and African median.[8] Officers in Liberia are not evenly distributed; most are concentrated in Monrovia. Bong (2008 population 333,000) Lofa (2008 population 277,000)[9] and Grand Gedeh (2008 population 125,000) counties each have only between 90 and 120 officers.[10] Some communities within the counties have only two or three officers assigned to their area, while others have no police officers at all.[11]

UNMIL and UNPOL have been extensively involved in Liberia’s security sector over the past 10 years—vetting, advising, monitoring, and providing logistical support to the LNP and the Liberian government. They have made it clear that there will soon be a drawdown. There are currently over 8,000 uniformed UN personnel in Liberia (down from the 15,000 immediately after the war), including more than 1,400 UNPOL officers.[12] In May 2012, Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon recommended reducing UN troop levels by 4,200 “blue helmets” by 2015.[13] The UN now says it aspires to bring military strength to 3,750 by 2015. The drawdown (also termed the “transition”) has slowly begun, with Liberia’s government assuming full control of policing in smaller police stations and more remote locations.[14]

UNMIL has estimated that Liberia will need 8,000 police officers, or about double the current LNP force, to adequately serve the Liberian public upon the UN’s departure. It has reported as a serious concern the lack of readiness by the police to take over internal security. In a 2012 report, the UN noted pervasive logistics deficiencies and the unprofessional behavior of some officers.[15] It also said that while efforts had focused extensively on the development of security institutions, less attention has been paid to the governance and accountability mechanisms of these institutions, which remain weak.[16]

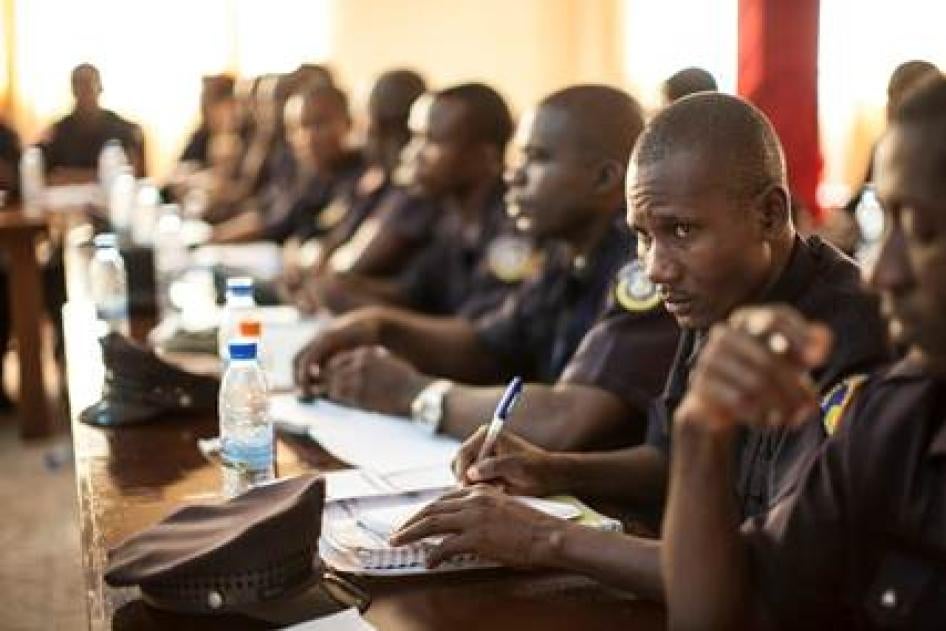

Officers attending a training provided by the Norwegian Refugee Council in Monrovia, May 2010. © 2010 Glenna Gordon

While UNPOL was initially heavily involved in vetting police officers, it now primarily serves as an advisory and monitoring force that also plays a substantial role in filling LNP resource gaps.[17] UNPOL monitoring can be credited with reducing the number of arbitrary arrests and detentions. UNPOL has done this through frequent visits to police depots and detention cells, where UNPOL staff check recordkeeping and speak with detainees.[18]

One resident of West Point, a section of Monrovia, told Human Rights Watch of the important role that UNPOL played in securing his release from police detention after his neighbor accused him and a friend of stealing a phone. He said police arrested and detained him without investigating the allegation, and that he was held for two days before an UNPOL official arrived, conducted an investigation, determined there was insufficient evidence to hold him, and requested his release. The man said, “If the UNMIL woman hadn’t come, I may have still been in the cell. It was so lucky for me that she did the check-in.”[19]

Unless prompted by UNMIL, the LNP has inconsistently monitored the length of pre-trial detention or scrutinized the quality of police investigations. While some nongovernmental human rights monitors are allowed in police detention centers, they do not have the capacity to monitor as frequently as the UN.[20]

UNPOL was charged with using “monitoring, mentoring and training … to improve the policing skills, management knowledge and professional capacities of the Liberia National Police [and] institute logistical and institutional reforms critical for improved, sustained and democratically principled national law enforcement in Liberia.”[21] UNPOL has played a critical role in the oversight and logistical support of the LNP, conducting joint patrols, monitoring the 48-hour limit of detention without charge, providing vehicle and other transportation and logistics support, and helping to mediate protests and major clashes with the police. In its absence, it is unclear whether the LNP will be able to reliably execute these core functions in compliance with international law.

Many UN officials in Liberia said that improving the quality of officers, not the quantity, should be the highest priority as the UN downsizes.[22] The need to professionalize the police has been perhaps most evident through the special inquiries that President Sirleaf has called for to investigate widely publicized instances of police misconduct. The two most recent inquiries occurred in 2011:

- In April 2011, Sirleaf created a Special Presidential Committee to investigate police violence related to student protests on March 22, 2011, when police beat a number of unarmed students, many of whom had to receive stitches. One student told Human Rights Watch that the police had stolen his phone while beating him, and he saw the police searching other students’ pockets for money.[23] The committee found that the force used by police was “excessive” and recommended that the police inspector general, Marc Amblard, be suspended for two months and that Deputy Director of Operations Al Karlay be dismissed.[24] Instead, Sirleaf gave Amblard a warning and suspended Karlay for one month.[25]

- On November 7, 2011, police clashed with the Congress for Democratic Change (CDC), an opposition party. The commission of inquiry that was formed to investigate the police violence on that day found that at least one person had been shot and killed, and others wounded, when one officer fired live ammunition into a crowd of protesters. The commission found that the police’s reaction to the protest was disproportionate, that it was ill-prepared for crowd control, and cited failure of leadership as a principal cause of the violence.[26] Based on the commission’s recommendations, Inspector General Amblard was dismissed.[27]

Aside from administrative action, such as suspensions and removals, no officers were ever charged for their actions in either incident, despite commissions calling for investigations and prosecutions.[28]

Governance and Corruption in Liberia

Since the end of armed conflict, the Liberian government has focused on enshrining the rule of law and has acknowledged how corruption has fueled abusive state agencies, contributed to Liberia’s past conflicts, and hindered proper security and economic development.[29]

However, despite the government’s programmatic goals, corruption remains a serious problem in Liberia, particularly in the security sector.[30] At the beginning of her presidency, Sirleaf announced that corruption was “public enemy number one,” and that reducing corruption throughout the government was critical to both Liberia’s economic recovery and its strengthening of accountability, transparency, and justice.[31]

Liberia’s government has made some noteworthy progress combatting corruption, notably by establishing the Liberia Anti-Corruption Commission (LACC) in 2008, which has the power to investigate and prosecute corruption cases, and establishing and by 2007 staffing the General Auditing Commission (GAC), which conducts independent audits of government agencies. The government has also required all commissioned officials to declare their assets, which the LACC then verifies.[32]

Nevertheless, these anti-corruption and human rights institutions remain weak. Although the General Auditing Commission has released numerous reports documenting mismanagement and irregularities, the government rarely acts upon these reports. [33] The LACC has secured several important indictments and convictions, but many civil society groups consider the institution to be under-resourced and ineffectual. Liberian human rights groups also found the Independent National Commission on Human Rights (INCHR) to be largely ineffective in investigating abuses or providing redress to victims. After two years in operation, it still had not developed the capacity to accept and process human rights complaints. Instead, it has mainly focused on human rights awareness campaigns. [34]

The US State Department has discussed Liberia’s ongoing corruption problem in its past few annual country reports on human rights practices. In its most recent 2012 report, it stated that, “ Low pay levels for the civil service, minimal job training, and few court convictions exacerbated official corruption and a culture of impunity.” [35] Transparency International, in its recent Global Corruption Barometer 2013, noted that in Liberia, people’s views on corruption in the country were among the worst in the world, that over 75 percent of those surveyed reported paying a bribe during the 12 months covered by the survey, and that the police were considered to be the most corrupt institution in the country. [36]

The president herself has faced challenges around corruption. In recent years, she installed her sons in Liberia’s cabinet, appointing them to prominent positions, defying media and civil society complaints of nepotism and conflicts of interest. [37]

In October 2012, Leymah Gbowee, who shared the 2011 Nobel Peace Prize with Sirleaf, resigned from her post as the head of the Liberia Reconciliation Initiative, citing the administration’s inadequate commitment to eradicating corruption. [38]

Security and Development

The government of Liberia has repeatedly acknowledged the links between human rights, a professionalized security sector, and human development. These links were seen most clearly in President Sirleaf’s Poverty Reduction Strategy (PRS) from her first term. This strategy underscored the critical role that the security sector plays in Liberia’s recovery and lasting peace: two of the four pillars of the strategy were security and rule of law (the other two were economic revitalization and infrastructure/basic services).[39]

Police officers conducting an arrest in Monrovia, Liberia September 2006. © 2006 Zoom Dosso/AFP/Getty Images

In preparation for the PRS report, the Liberian government consulted the public about its expectations and priorities, and discovered that while “security had improved since the war,” there were “several common internal security concerns.”[40] Principal among these concerns were “a shortage of qualified security and police personnel, incidence of police corruption, and low levels of public confidence and trust in the police.”[41]

International organizations have reported on the negative impact that police corruption can have on the recovery of post-conflict states. In a 2011 report, the US Institute of Peace found generally that:

Diplomats, aid administrators, and other field personnel report that police corruption wastes resources, undermines security, makes a mockery of justice, slows economic development, and alienates populations from their governments. Their stories and the findings from general surveys reveal a fundamental obstacle to fulfilling the basic, widely proclaimed objective of most interventions the international community undertakes, namely, establishing the rule of law…. Eliminating police corruption is required for any country that has establishing the rule of law as a national objective. Ignoring this imperative means that international efforts at nation building proceed at their own peril.[42]

I. Paying the Police for Justice

I don’t go to the police for anything. They always want from me and I don’t have.

–A 36-year-old woman, Monrovia, January 2013

Police corruption severely impedes proper administration of justice and denies Liberians their basic rights to personal security and redress, including equal protection under the Liberian constitution[43] and international law.[44]

Corruption compromises the state’s duty to protect all Liberians from violations of their human rights. It fuels abusive practices such as arbitrary arrest and detention, since arrests and releases are often done through bribes and extortion, [45] undermining the constitutional provision that “[j]ustice shall be done without sale, denial or delay.” [46] It harms the victims of crime as well as alleged perpetrators, deterring those, particularly impoverished people, from seeking help from police for state services. And it works against the Liberian government’s post-war goal of establishing trust between the police and the public.

Victims of police corruption reported that the police can extort money at every stage of a investigation, whether for a common crime or a government rights violation. Many told Human Rights Watch that because of routine demands to pay bribes, they would no longer report crimes to the LNP. Several said they decided to drop their cases because they could not afford monetary demands made by police.

Poor investigative practices make it difficult for the government to prosecute cases. Human Rights Watch spoke to several individuals in the judiciary who noted that judges must often throw out charge sheets and dismiss cases due to little or no fact-gathering by the police. [47]

Many people expressed a growing distrust of the police’s capacity to protect the public. Victims of police corruption repeatedly told Human Rights Watch that “justice is not for the poor,” or “no money, no justice.” This has been one of the most pernicious results of ongoing corruption in the LNP—the perception that wealth, not guilt, determines the outcome of a case. One Liberian summarized, “They don’t even investigate. If you go there and pay money, you’re right.” [48]

Payment to Register a Case

Payment to register cases in Liberia is widely recognized, including by the police, as a common, if unlawful, practice. Despite the LNP leadership’s public condemnation of the practice, many police depots require complainants to pay a “registration fee” for desk officers to register a complaint or file a case. Crime victims told Human Rights Watch that the police had asked them to pay to register their case or demanded money before following them to the crime scene. Except for the demand for a “registration fee” at the police depot, they were never given a reason for the payment.

Of the individuals Human Rights Watch spoke with, registration fees ranged from 150 LD (US$2)[49] to 500 LD ($6.75).[50] The most common amount paid in 2012-2013 was about 250 LD ($3.30).[51] While these amounts may seem inconsequential, in a country in which over 90 percent of the population live on less than $2 a day, this is a significant sum.[52] Even those who described the fees as “small small” or a “small thing,” often admitted that for the poor these were large amounts that prohibited them from seeking needed police assistance.

Registration and other fees even occur when the perpetrators of the crime are the police themselves. One woman from Monrovia described how a group of officers from the Police Support Unit (PSU) robbed her and several other women of their valuables while they were outside a house at night.[53] The woman said she and the women tried to file a complaint with the West Point depot but were asked to pay 500 LD ($6.75) to register the case. They did not have the money. She recalled, “After that, we left it. We don’t go back there [anymore].”[54]

Transportation and Other Logistics “Fees”

Victims of crimes are also often asked to transport the police to the scene of the crime, or to pay for such transport. Police officers seek to justify these charges by referencing their poor logistical support, such as lack of fuel or vehicles. Human Rights Watch spoke with police officers who expressed dismay at their inability to respond to victim complaints because of lack of fuel or a working vehicle. However, transportation fees can also be another cover for corruption.

Demands for transport come in a number of different forms. Police may ask the victim to pay for fuel for a working police vehicle. If vehicles are not available, the police may ask the victim to pay for their transport by motorcycle taxi (pehn-pehn) or taxi cab. Sometimes officers ask for the money outright; other officers have victims ride alongside them and pay the taxi fee upon arrival at the accident scene. That these fees are often bribes becomes clear when officers ask for cash that exceeds—often by substantial amounts—the usual taxi fare to the accident scene. One person said he was asked to pay 1,000 LD ($13.50) to transport the police to a crime scene that should have cost no more than a couple hundred Liberian dollars.[55]

Others told Human Rights Watch that they had been charged a “walking fee” for officers to respond on foot to their complaints. A group of women in West Point, said that they had tried to minimize walking fees and other fees in connection with domestic violence and rape cases since such fees effectively prevented many women from filing complaints. The group’s leader said, “When women are bloody and they get to the police, they say ‘walking fee,’ and the whole case comes down. We formed our group to enforce the law.”[56]

Payments for Release from Police Detention

It is common for people held in police custody or detention in Liberia to pay the police for their release—regardless of whether they are innocent or guilty of the alleged crime. But police sometimes even demanded payments when charges had already been dropped.

Payments for release take several different forms. The police sometimes told the accused to pay for the case to be dropped and to leave the station before the person was formally charged. One woman said that after she was arrested, the police told her that she was at fault in a dispute with another woman and that she had to clear her case to avoid placement in a police detention cell. She told Human Rights Watch:

They wanted to put me in a cell, but I appealed and begged. They had mercy on me and told me to pay a certain amount. [It was around] 400 to 600 LD [$5.40-$8.10]…. I paid the police because they said, “You need to clear this.”… I was afraid to go to jail. I gave the money to the boss man [the officer in charge of the depot].[57]

Others told Human Rights Watch that, after paying the police, they were released from a detention cell. In such cases, charges were almost never pursued; the payment to the police effectively ended the case—and perhaps deprived justice to the victim of a crime.

A secondary school student told Human Rights Watch that he was put in police detention without any formal charges after a woman lodged a complaint against him. His mother was asked to pay the police to let him go free. He said:

My mother came and she had to give them money in order to release me—about 500 LD [$6.75]…. [T]hey released me and they told us we could go. It made me feel like I was being cheated [by being jailed with little explanation and no follow-up]. They didn’t really explain what happened; they just took me and put me in jail. It makes me feel like the police aren’t really doing their job.[58]

Human Rights Watch also received several reports from domestic human rights organizations about police officers attempting to charge “bond fees”—bail—to release detainees. [59] Liberian law only empowers the courts to issue bond fees; [60] the police were engaging in an illegal practice.

As a result of police malfeasance, those who wish to pursue justice are denied that right. Similarly, those who should be held accountable for their crimes—notably those with enough resources to pay their way out—routinely escape accountability, and could pose a security threat to others.

Mob Violence and Vigilante Groups

Many Liberians told Human Rights Watch that people distrust the police’s ability to properly investigate crimes or protect them from violence, which encourages popular support for vigilante groups and mob violence to achieve “justice.” Liberian newspapers frequently display photographs of mutilated faces and bodies after a vigilante or mob attack. A county magistrate summarized, “The way police handle matters, it makes people want to take matters into their own hands.”[61]

A young man is beaten with sticks after being accused of attempted theft in Monrovia, February 2007. © 2007 Reuters/Christopher Herwig

One street vendor in Monrovia said:

When you see someone stealing, we give the alarm. We usually do it to stop them and put fear in them. They say, “Rogue! Rogue!” Then you can be caught. Sometimes if [the suspects] still have materials in hand, we chase them. We ourselves are against the police. When [the suspects] are caught [by the police], they are often released. [W]e don’t know if they [gave] the police money. So we feel like any time we catch them, we beat them.[62]

It is common practice for a crime victim to shout “rogue”—the word used for a thief—and for those nearby to chase down the accused and beat him with fists, sticks, and machetes (called “cutlasses”). The most recent UNMIL secretary-general report cited 31 instances of mob violence for a six-month reporting period, between August 2012 and February 2013.[63] This number is likely low, since UNMIL relies on the LNP for data on mob violence.[64] The LNP’s data reporting methods are weak and the force still lacks a presence in many communities. Moreover, all the factors that deter people from going to the police in the first place—such as paying fees to register cases—discourages the reporting of mob violence and reduces the likelihood of such crimes being registered with the police.

One young man in Monrovia said that his community had begun to pool their money to pay for a vigilante group to patrol at night:

In the community now we have a vigilante group. We pay them, because the police are doing nothing. Each house pays 300 LD ($4) a month. We have about 300 houses in the community…. In the nights they will be at some strategic points and even patrolling the community…. They can have cutlasses and sticks in their hands.[65]

There is no reliable data on the number of vigilante groups in Liberia, so it is difficult to know whether their prevalence is increasing or in decline. A number of people told Human Rights Watch that they feared mob violence would increase with the UN’s drawdown.

II. Police as Predators, Not Protectors

The police and other security agencies will be trained to cooperate closely in a structured system of national, county and district-level security committees, which also involve local government, [sic] is important in gaining the confidence of local communities to combat crime and underpin the rule of law and is a key ongoing part of the Government’s efforts to improve human and economic security.

—Government of Liberia, “Poverty Reduction Strategy” (2008)

I feel like the ERU [Emergency Response Unit] and the armed robbers are the same people, because what the ERU [did to me] and what the armed robbers [do]…was the same thing.

—30-year-old woman, Monrovia, December 2012

The brunt of daily police bribery, extortion and theft in Liberia is borne by those in society scrambling near the bottom of the financial ladder to feed themselves and their families. These are the street vendors, motorcycle drivers, and taxi drivers living hand-to-mouth whose commercial activities put them in constant contact with police at checkpoints, random stops, and street raids. They are both easy to target for abuse and pose little risk of enforcing accountability.

Liberia’s police, instead of upholding the rule of law and the rights of individuals, are all too often preoccupied with supplementing their salaries—and those of their superiors—through criminal activity. These activities are not only harmful in themselves, but displace regular police functions such as patrolling and responding to reports of crimes.[66]

While those on the fringes of the economy are not lucrative targets individually, they are en masse and over time. Repeated small-scale extortion adds up, and those engaged in small-scale commercial activity are less likely or able to refuse to pay bribes or report police abuse. Such individuals who spoke to Human Rights Watch often did not know where to report abuse beyond their local police depot, were worried about reprisals for reporting, or did not understand that police demands for money were illegal. For many Liberians, the police act more like predators, extorting and taking what they are able, rather than protectors of their rights.

Police officers in Liberia use numerous methods to extort money from residents, including both routine demands for bribes at checkpoints and more open and brazen shakedowns of poorer communities at night. During police patrols, officers approach or follow residents, and under the pretext of searching for contraband items or weapons, pat them down for money. Members of the armed police units—the Police Support Unit and Emergency Response Unit—committed almost all the cases reported to Human Rights Watch.

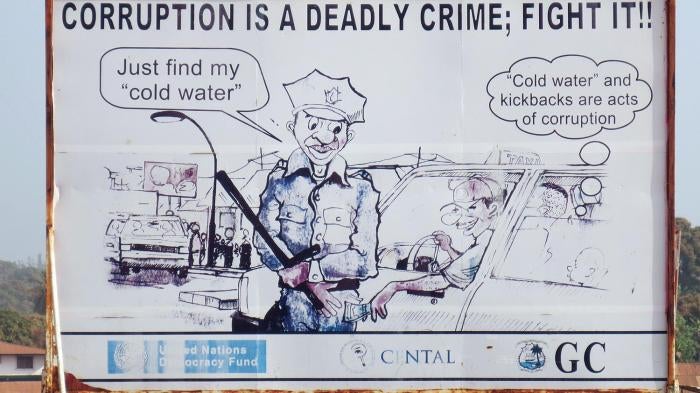

Of course, bribery requires two parties, as has been emphasized by the police leadership and a bumper sticker campaign across Liberia. [67] But most motorcycle taxi drivers and street vendors said they believed that they would not be permitted to pass through checkpoints, or receive their impounded goods or motorcycles, without paying the amount that police demanded. The drivers and street vendors said they try to beg or haggle with the police for a reduction in the illegal sum, often to no avail.

A number of police officers confirmed to Human Rights Watch that harassment was used as a money-making scheme. Several of these officers said they participated in “Susu,” or savings clubs, in which they would pool the daily money they had made from extorting taxi and motorcycle taxi drivers and others. One officer explained:

Three to four [of us] are in the office. Every day we bring 150 LD ($2). At the end of the week, we all give it to one person. The Susu is like a safety…. It is like helping one another. How do you get the money to pay your Susu? It is through harassment. There is no love for the job.[68]

An officer from the Professional Standards Division, which has a Public Complaints section that receives the public’s reports of police abuse and an Internal Affairs section that addresses officer complaints against other officers,[69] elaborated:

In the Red Light area, officers are putting daily Susu there. Can you imagine? You [the officer] are not in business. Where is that money coming from? Even in my office now, [an] officer was transferred to us, [and] he was transferred back. He said—no money here, so I am going back to traffic.[70]

The LNP’s inspector general has publicly requested that citizens report incidents of corruption directly to him.[71] Such actions, which have shown no discernible effect, may give some public airing to an issue, but are no replacement for comprehensive government action to discipline and punish police officers engaged in illegal activities.

Armed Shakedowns

The armed Emergency Response Unit and the Police Support Unit appear to be especially involved in robbing Liberians under the pretext of carrying out their duties, misusing their weaponry for their financial advantage. Such actions are common at night, when these units patrol the streets—especially in Monrovia—and should be protecting Liberians from violent criminals.

The ERU, with an estimated 321 active officers,[72] is a “quick reaction force” that the government established after the war to respond to major internal security breaches.[73] The PSU, numbering about 681 officers, was formed for riot control and to respond to violent crime.[74] Most of the theft or robbery cases reported to Human Rights Watch involved one of these two units and frequently involved the victims being beaten before their belongings were stolen.

Police officers on nighttime patrol in Monrovia, Liberia. © 2011 Espen Rasmussen/Panos

The PSU, and sometimes the ERU, patrol Monrovia’s impoverished West Point area at night and harass those found outside their homes. One man said that in October 2012 PSU officers robbed him and his wife at night outside their West Point home. The officers kicked him, held his wife at gunpoint, and seized money from her bra, he said.[75] The officers made off with their money and phones.

A woman who said she was robbed by six PSU officers in 2012 while sitting outside her house at night told Human Rights Watch:

In the night, we can’t bring nothing outside. We can’t even carry [a] phone with us outside. [Maybe] once in three weeks [they come]. They can “charge” people in the night [robbing them through shakedowns]. They use the baton. If you put up resistance, they beat you with it. I have seen them beat somebody with it in front of me. This started last year. When they cause trouble, they wait for people to forget and then they come back. They usually come at 10 or 11 at night.[76]

These shakedowns resemble tactics that were used by government security forces during the civil war to pay themselves.[77] Although the police and military personnel now receive regular salaries, these practices persist. A police officer who works in West Point confirmed that their depot sometimes received reports about PSU shakedowns. The officer said:

On a daily basis, they [the PSU] patrol. Sometimes we get complaints [about] them, but we are not the authority for them. So we send people to Central. Some people complain that they “charged” them.[78]

The police command structure makes it especially difficult for the regular police to report on abuses by these two armed units. While both are under the direction of the LNP, Monrovia-based police officers generally report to either ERU and PSU commanders in Monrovia or senior-ranking officers. Any reports of ERU or PSU criminal activity might go to the very unit implicated.

ERU harassment occurs in both urban and rural communities. Community members from Grand Gedeh County told Human Rights Watch that the ERU sometimes used violence against residents to rob them of their valuables or goods.[79] One community that spoke with Human Rights Watch described multiple violent encounters with the ERU since 2011. These included one individual being tied up, beaten and robbed, and on another occasion, ERU officers storming the town with tear gas and batons when they received an inaccurate report about the town stealing zinc.[80] The town chief and leaders said that for over five years they had experienced no violent brushes with the regular LNP officers before the ERU arrived. Residents and UNMIL officials noted that this type of violence and theft increased notably after the ERU deployed to Grand Gedeh in response to the 2011 crisis in Côte d’Ivoire.[81]

III. Police Extortion and Other Abuses in the Informal Sector

Much of the commerce in Monrovia and other Liberian cities takes place in the streets, with vendors dotting busy corners and countless motorcycle and automobile taxis weaving in and out of traffic. Many of these low-income jobs are held by young people, typically with little formal education and who are returned refugees or were internally displaced during the civil wars. Because these street sellers and drivers are accessible and vulnerable and have little means to assert their rights, they have long been regular targets for police extortion. As many told Human Rights Watch, when a police officer demands money, if they want to be able to continue their work, they have little option but to pay.

In a country where relatively few people enjoy the benefits of formal sector employment, jobs like these and others in Liberia’s informal sector are the main income source for many families. In a 2011 report on the Liberian labor force, the Liberia Institute of Statistics and Geo-Information Services estimated that 68 percent of Liberians work in the informal sector and 78 percent are considered vulnerably employed. [82]

The Liberian government has recognized the importance of small-scale entrepreneurship and its critical role in poverty alleviation. It has also noted that small business provides earning potential to perpetually underserved groups, such as women and youth. A 2011 paper on small, medium, and micro enterprise by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry stated:

As the main source of income for the great majority of Liberian people, perhaps 80 percent or greater, microenterprises are the lynchpin of family welfare in Liberia. Households with successful microenterprises that generate reasonable, steady revenues are positioned to finance better health services, housing and education for their families. Those with marginal microenterprises that generate minimal, unstable revenues manage only to keep from falling into dire poverty.[83]

Yet it is these low-income workers and their families that are most vulnerable to police extortion and its attendant abuse, including arbitrary arrest and detention, assaults on the person, and mistreatment in custody. Losses of income, as well as the ability of street vendors and drivers to earn an income, create immeasurable hardships for their families.

Street Vendors

Ongoing ambiguity in Monrovia concerning city zoning policies and national law regulating street vendors has generated confusion that the police exploit to extort money and commit other abuses. Under the pretext of enforcing these laws, the police steal or “lose” goods confiscated from vendors during raids, or require that vendors taken into custody pay “fees” to be released from jail. While seizure of street vendor goods occurs across the country, it is the most pervasive in Monrovia. Almost every street vendor that Human Rights Watch spoke with in Monrovia had experienced seizure of their goods several times in the last year. One street vendor described the impact of police harassment:

The PSU, MCP, LNP—everyone can arrest your goods.... We don’t know what to do…. My father died when I was very small. So for me I pay my school fees. I am supporting my brothers and sisters. We always say the strong will survive because nothing else will do.[84]

Even small sums taken by the police can have a significant impact on those in the informal sector. Street vendors, many of them women with children, told Human Rights Watch that they chose to sell sandals, clothes, and other small items because there were no other job opportunities. They use the little they make to feed and educate their children. Young women especially said they sell goods on the street to put themselves through high school. A 2007 study estimated that street vending (also calling “street selling” or “petty trading”) was the main income source for 38 percent of the women in Monrovia and 17 percent of the men.[85] Noting that women conduct 85 percent of agricultural marketing and trading, the Sirleaf Market Women’s Fund stated in a 2012 report:

[M]arket women working in the informal sector are a critical component of the current Liberian economy; not only do they grow most of the food but also, through income earned from their market activities, feed most of the population.[86]

Police raids can have a substantial economic impact on the vendors, who told Human Rights Watch that after a raid they were sometimes unable to buy food or pay school fees. Some former vendors said they left this occupation because the raids in their area were so bad that they perpetually lost money to the police.

One 30-year-old street vendor who sells clothes in Duala, a busy market area of Monrovia, recalled that, after a raid, she tried to get her market goods back from the police, but she was unsuccessful. She recalled that the goods were worth almost US$300, and the loss of this potential income crippled her ability to pay her children’s school fees.[87] As a result, she had to take her two children out of school. She explained that, for all of 2011, she was unable to sell, because she could not amass enough funds to reinvest in her market goods. In 2012, she was finally able to secure a loan from the bank to purchase market goods to sell. However, her family continues to struggle. She said:

I got no one to help me for the children’s fees. The big one [is] in school [now], but the small one, no. She is 11 years [old], in 4th grade. She wants to be in school, but [there’s] no money.[88]

Human Rights Watch interviewed 27 street vendors, mostly working in Monrovia. Police harassment, extortion, arbitrary arrest, and violence against street vendors occur most frequently in heavily populated market districts such as Duala, Red Light, and Waterside, among others. These sellers said that the most common form of harassment was police raids. In such instances, police officers drive one or two police pickup trucks into heavily populated market streets. When the street vendors see the police coming, they collect their goods and begin to run. The police chase after the sellers and seize whatever goods they can. Sometimes, the vendors try to negotiate with the police to get back their goods.

Street vendors arrange their goods for sale in Red Light, a market district in Monrovia. © 2010 Glenna Gordon

A couple of street vendors noted that, when they could not pay the bribe, police officers took a portion of their goods as in-kind payment. More often, street vendors said that the police throw the goods in a plastic bag, or sometimes simply leave the goods loose in the pickup, and carry the goods to the police station. One street vendor described a recent raid:

Last week Friday, was the last time it happened…. I was selling on the sidewalk. I tried to run, but I couldn’t make it. When you see the police, you try to run. I ran in the store, and they ran in there and they took the goods [which were in a box].… They carried it to Slip Way depot. I went for it, and they told me to pay 1,500 LD ($20)…. When I went to them to pay for the market, it was not correct. Seven pieces were missing. I shed tears when they took the goods and when they gave me the goods that were not correct. They told us not to sell in the streets, but this is the only thing we can do to survive…. I had to [borrow] money from my friend to buy food for my family.[89]

Street vendors in Monrovia recalled going to the police Central Headquarters as well as local depots in areas like Slip Way and Red Light to collect their goods, only sometimes to find that more than half of their inventory was missing. Other times, their goods were nowhere to be found. There is no tracking system in place for when goods are seized, which perpetuates the loss and stealing of goods. Street vendors told Human Rights Watch that they frequently paid money directly to the police to collect their goods from the depot.

Police also sometimes arbitrarily arrest sellers and make them pay for their release:

They took my sister and myself to Zone 1…. I was selling in the market and the police came and while we were running they grabbed me, handcuffed me, and put me in the car. I don’t know [why they handcuffed me]…They put me in the cell, and I slept there. I was there the whole day. [T]hey said I should pay money to them before they freed me—500 LD ($6.75).[90]

During raids on street vendors, police sometimes commit beatings and other violent abuses. One street vendor said that he and other vendors had gone to the warehouse where they keep their goods, with the intention of cleaning and restocking it. He said that the police then arrived:

[The police] were running behind our children when they reached [us]…. I asked them why they were using abusive language and telling us to “take the fucking [food]” from the road. When they came in the [warehouse] fence, they said we should [clear] the road for them to pass. They were calling the food shit. Five police men jumped me and took me to the police station. While they were jumping me, they put their hands in my pocket. They took [my] phone and $25. They beat me, [and] after they finished beating me, they put me in the handcuffs and we [left].… [There was] no investigation. I went in jail. Later on [someone I knew] came, and she had to talk for me. They said she must “clear the desk” [a term used to ask for a bribe for release from detention] before I could be released. She paid small thing—450 LD [$6], and she freed me.[91]

Beyond the immediate harm of the police raids on street vendors was their longer term financial and psychological impact on families living on the margins. A 24-year-old street vendor told Human Rights Watch:

I’ve sold in the market for almost seven years now. Each [time] the police come around, they take your market [goods] and carry it. Sometimes, when you don’t give your market, they beat you. They take you to Central [Headquarters]. You can’t get it, and you start all over again…. I sell to pay my school fees to go to school at night. That is the only way I can sustain myself. If I don’t sell, I won’t feed myself. If I don’t sell, I can’t feed my son.[92]

Another street vendor elaborated:

I am a high school graduate. I don’t have any money, so I decided to sell to get bread for my aunt and me. But each time we go to sell, the police take our market. They are [supposed] to come and save our life, but they come to destroy us.[93]

Motorcycle Taxi Drivers

Sometimes, they [the police] eat more than we [make]. The small thing you save, you have to take it and give it to them…. If you are running the motorcycle [making money for yourself], you don’t even have an intention to steal, because you can get small thing [from your work]. But the police are always [running after us, taking our money]. They say they are there to protect life and property. But [t]hey are killing me slowly.

—24-year-old motorcycle taxi driver, Lofa, February 7, 2013

At a May 7, 2013 forum on “Partnering for a Shared Vision of Liberia’s Economic Future” in Washington, DC, Finance Minister Amara Konneh responded to a question about youth unemployment by emphasizing that many young people were pursuing self-employment. He specifically highlighted motorcycle taxi drivers as an example, stating that these young men had “become critical in our economy, filling a void in transport.”[94] Yet the government has done little to protect these entrepreneurial activities from police corruption and its harmful impact.

Motorcycle taxis have been an important source of income for young men who have low levels of education or have lost family in the wars. A number of them are ex-combatants from the civil wars: the motorcycle drivers union estimates that 25 percent of motorcycle taxi drivers are former fighters. [95] The motorcycle is how they sustain themselves and their families financially. [96]

Motorcycle taxi drivers wait for customers in Red Light, Monrovia. © 2010 Glenna Gordon

Human Rights Watch interviewed 37 motorcycle taxis drivers (also called pehn-pehn drivers) throughout the country who reported frequent extortion, harassment, arbitrary arrest and detention and physical abuse from the police. Extortion and abuse take place at official and ad hoc checkpoints that are common along the country’s major roads and at random stops. Police officer demands at checkpoints vary greatly. A representative of the Liberia Motorcycle Transit Union (LMTU) told Human Rights Watch:

There’s no security [at the checkpoints]. People are only there to satisfy their own desire, improve their salary…. If you don’t have money, it is difficult to trust the checkpoint. You believe that only your money can speak for you. Security is like a business.[97]

Motorcycle drivers said that police officers are often assigned to checkpoints alongside other security personnel, such as those in the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization or the Forestry Development Authority, each of whom wants their share of the checkpoint bribe.[98] One motorcycle driver explained why more motorcyclists did not resist extortion at the checkpoints and other random stops, especially where armed units were present:

Because they have pistol, when they say you must pay, you have to pay…. If we were people with good money, we could take people [the police] to court. But we don’t have money to pay.[99]

Motorcycle drivers are also often targeted on “inspection days,” when the police routinely confiscate their bikes, which can only be recovered by paying bribes. The most common amount cited by motorcycle drivers was 500 LD ($6.75) to free the motorcycle from police custody, but several drivers described paying as much as 1,000 LD ($13.50) or 1,500 LD ($20). On such days, it is not uncommon to see dozens of motorcycles lined up outside police stations.[100]

Motorcycle drivers in different parts of the country said they were beaten, injured, detained, arrested, or had their motorcycles seized when they tried to proceed through a checkpoint without complying with the monetary demands of the police. Sometimes, drivers said, they could negotiate their way through checkpoints.

A leader of the LMTU explained the human cost of police corruption for many motorcycle drivers:

Most of the children, they lost their parents [during the civil wars]. They are borrowing bikes to take care of themselves. Some of them, they can’t send themselves to school. They are using the motorbike to survive. There is no one to talk for them. The LNP needs to encourage the children instead of harassing.[101]

|

Alex’s Story Alex,” a pseudonym, was orphaned at a very young age. He told Human Rights Watch: I don’t have father or mother, but I want to go to school. I want to learn. They killed my father and mother during the war. I decided to ride motorbike so that I would be able to support myself. [102] Alex worked his way through elementary school in Lofa County with the help of a farmer, who had taken him in after he returned from a refugee camp in Sierra Leone. He moved to Monrovia to continue his education when he discovered an uncle lived there. I was eager to come to the city to continue my education. [But] when I came to the city, I started to struggle…. [There was] no one to pay my school fees continuously, [so my uncle] decided to call someone to help me ride the motorcycle. [103] Alex uses the money he makes from riding the motorcycle in order to pay for his education. Police corruption has created a constant strain on his ability to complete his schooling. Alex explained one incident that caused him to leave school for the year: There is one police in Logan Town who is always harassing me for money. He chases me for money. One day he was chasing behind me, and I had an accident. That happened in 2011. The motorcycle had its own damage. So the owner of the motorcycle ordered me to pay for it. I was in 11th grade at that time. That caused me a lot of problems in my school. I am the one who pays my school fees. I don’t have anyone to help me. Alex explained that when he had the accident, he used the money he had saved for his schooling to fix the bike. Without school funds, he had to drop out. In addition, the motorcycle owner took the motorcycle from him after it had been repaired, which created further financial strain. Eventually, he was able to save enough money to go back to school, but he explained that it is a daily struggle to make sure he has enough money to pay both the police and his school fees. “For now, I am still trying to finish. I am in 12th grade now.” [104] Alex noted there was a risk in reporting police corruption and abuse because police officers often live near communities where they work. Given the fear of reprisal, he said he would not risk reporting police corruption. Instead, he hopes that the police will change: I want the police to become friends for us. I want them to know that some of us are on the motorcycle to fund our education, so they have to give us chance. If every day they are harassing us, how will we be able to do something good for our future?… [F]or motorcyclists, we are just like [the] army. Every day you have to expect to die. Because if you don’t hit car, car will hit you. We just want [the police] to help us, to provide our protection . [105] |

Police officers who apprehend motorcyclists at the checkpoints also sometimes arrest the drivers and demand bribes for their release from detention. One motorcycle driver explained how he was arrested and detained when an officer randomly stopped him in town. He said he was tying a jug of gas to his motorcycle for a trip into the forest when an officer accused him of selling marked up gas, and arrested him. The driver explained, “[Even though] he understood that I was not selling the gas, he jailed me. I was there the whole day.” He noted that the fish he was carrying spoiled, costing him 2,500 LD ($33.78). The officer also made him pay 300 LD ($4) to be released from police detention.“I felt bad, because there is nowhere to carry a complaint,” the driver said. “They are using us as business. Any time police stand at the street, they take money from us.”[106]

Almost all of the motorcycle and taxi drivers who spoke to Human Rights Watch knew that any fines they received required a proper ticket outlining their offense, rather than an informal payment to the police. The ticket should be brought to the Ministry of Finance, where tickets are paid. The ministry should give the ticket holder a stamp, permitting the driver to recover his motorcycle, remove his name from a list of drivers wanted for trafficking violations, or whatever the issue might have been.[107]

However, attempts to enforce this system and resist or report police misbehavior are met with resistance and retaliation from the police. Two advocates on behalf of the motorcycle taxi drivers spoke about their efforts to advocate for the removal of an ad hoc checkpoint in one county. An LMTU representative explained that the officers had set up a checkpoint with a rope in the middle of the town and were carrying on “vehicle inspection” for the motorcycles. “They would say: you are overloaded, no helmet…. [There were charging] 200/300/500 LD [per person].” The LMTU representative said that the officers had a plastic bag into which they were collecting all the money. He and other LMTU representatives went to see what was happening and to speak on behalf of the riders:

When we told them that what they are doing is illegal, they began to call for reinforcement and said we were beginning to incite riders against them. A pickup came [for us]. They put us in the cell. We were in jail for a whole [day]…. We called a lawyer…. There was no charge sheet. We paid 4,475 LD ($60) to be released. They didn’t issue a receipt. There was nothing.[108]

Since the Professional Standards Division does not exist in Liberia’s counties, motorcycle drivers and others must report any complaints they have about police officers directly to the depot or county commanders and rely on these commanders to take appropriate action. Motorcycle drivers told Human Rights Watch that the depot commander is often present and thus aware of motorcycle seizures or corruption at the checkpoints. Because of this, drivers often said it would be futile to report police abuses to the commander.

Motorcycle taxi drivers appeared to have a more positive view of the police where the predatory behavior towards them was minimized—such as in Voinjama, the county capital of Lofa County. Motorcycle drivers who mostly rode within and near Voinjama stated that if they did not have bribe money, officers often let the motorcyclists pass without detaining or arresting them. Riders noted that sums demanded by the police were low, around 10 LD ($0.13). These motorcycle riders also voiced a greater faith in the police and their efforts. One motorcycle taxi driver commented,“[The police] are helping. All the time, they are correcting us. Sometimes they say—man you are carrying heavy load. Don’t do that.”[109] Conversely, motorcycle riders who traveled to areas in Lofa where they experienced aggressive police extortion tactics expressed a more negative view of police.

Taxi Drivers

Taxi drivers experience many of the same abuses from police as motorcycle taxi drivers. Human Rights Watch spoke with 25 taxi drivers who drove through many different areas of the country. They told Human Rights Watch about the harassment and extortion they encountered at checkpoints, arbitrary detention when they were unable to pay the amounts demanded by police officers, and police violence in connection with extortion and theft.

Taxi drivers noted that one common way for police officers to extort money was to threaten the driver with a ticket that was triple or quadruple the amount of a bribe. This could happen at checkpoints or at random stops on the roads. Officers would tell taxi drivers that they were overloaded or that they had engaged in improper driving, and the taxi driver would be given the option to either pay a bribe—usually between 300 and 500 LD ($4-$6.75), or they would be issued tickets that could be priced as high as $50.[110] Taxi drivers said that such tickets often surpassed their financial means, so they would pay the bribe demanded.[111]

One taxi driver described how the police had removed the batteries of 13 taxis parked at Red Light to obtain bribes:

They said it was 500 LD [$6.75] each [to get the batteries back and go on our way], but if we didn’t pay the 500 LD each, they would issue a 2,500 LD [$33.78] ticket. The drivers were scared of the ticket, so they paid [the] 500 LD.[112]

Red Light is so overrun with police officers that an unofficial system has been set up to move taxis through the area without having to stop to pay an officer. This system involves a “fee” for officers to “escort” taxis through Red Light to the nearby Parker Paint area. Drivers report this fee as averaging around 100 LD ($1.35); whereas, drivers can pay 500 LD ($6.75) or more if they are stopped by an officer and told to pay in exchange for not being issued a ticket.[113] One taxi driver said, “We don’t even know [the] main police assigned to Red Light. Everyone is just floating there.”[114] Another taxi driver noted that officers should be wearing their badges so that witnesses of corrupt practices could report abusive behavior, but “many of them don’t use [wear] it.”[115]

Human Rights Watch spoke with several representatives nationwide from the Federation of Road Transport Union of Liberia (FRTUL) who discussed the problems of drivers trying to protect their rights. One explained:

[I]nstead of enforcing the law, they [the police] are there to pollute the system. There is no system in place. Most of the drivers are not educated. So to take the matter to the traffic board, they are afraid. They would rather pay the money…. Those who are illiterate, there is fear. If you know the law and your rights, [you] will not allow someone to prey on you. [But] [t]here is a risk for the drivers; the police may deal with them even more [harshly] than that [monetary demand].[116]

Many taxi drivers who spoke to Human Rights Watch said that their primary concern with the police was extortion and detention at the checkpoints and through major market junctions. However, several described cases of police ill-treatment that occurred under the pretext of a police investigation. One driver recalled:

The woman [who was a passenger] talked to me—she said [her] cell phone was lost. I said I have not seen it. She called the phone. It was ringing, but not on me and not in the car. She still called the ERU…. They searched the car, but they didn’t see anything…They took my money—1,500 LD ($20). They told me to “charge myself.” I was outside the car standing. They [then] just jumped on me and started beating me [for] more than 15 minutes. They beat me with stick and [baton]. [They] beat me on the arms and neck. There were about six. They beat me and I lay down on the ground. I was crying. I wasn’t even able to swallow my spit. I was on the ground and the union people carried me into the house. I lost a lot of blood…. I didn’t complain to people. I left it with God. I didn’t have anyone to complain [to]. The union said they would see after it. The said it would receive my money, but I have not seen it.[117]

IV. The LNP and Corruption

Corruption in the Liberia National Police does not exist in a vacuum. Many factors contribute to corrupt practices in the police force. Police officers, civil society activists, and UNMIL personnel all noted that gaps in crucial logistics, such as fuel, vehicle maintenance, and basic supplies like pens and paper, encourage and exacerbate corrupt practices.

Lack of accountability for corruption, especially at the highest police and government levels, remains a barrier to a more professionalized police. This lack of accountability, coupled with poor systems in place for promotion, assignment, and resource allocation, can effectively penalize those officers who are unwilling to engage in corruption.

Police corruption violates Liberian law and contravenes policies in the LNP Duty Manual, governing its operations. Beyond the direct harm to those affected and the broader societal impact, rampant police corruption also impedes security sector reform that the Liberian government has acknowledged is critical for post-conflict peace and recovery.

United Nations Police has provided extensive monitoring and oversight for the LNP. Many officers noted that UNPOL stopped by their depots, sometimes daily, to check their books and inquire into day-to-day operations. UNPOL’s monitoring has largely been to enforce certain protocols, such as ensuring that detainees are either brought before a court or released within the 48-hour detention limit. UNPOL has also been a crutch for the serious logistical shortages in the LNP, most notably for vehicles and fuel supplies, but also for stationery and smaller items. Logistical support from UNPOL has been especially pronounced in the counties.

UNPOL has not, however, been able to extinguish the flow of corruption in the LNP. Both officers and citizens expressed trepidation at what might lie ahead when UNMIL is no longer present to assist with logistics shortfalls and regularly monitor the police.

The following discussion sets out factors contributing to, but not justifying, police corruption in Liberia.

Logistical Support