The Deported

The Trump administration has dramatically ramped up immigration arrests inside the US while it scapegoats millions of people by painting them as violent criminals who should be deported. The administration claims it is focusing on serious, violent criminals, but President Trump’s new policies make every unauthorized immigrant a target, regardless of their actual criminal histories. The crackdown is also sweeping in immigrants who are legal residents but who have been convicted of sometimes only minor or old criminal offenses.

Many of these deportations threaten a range of fundamental human rights including the right to family unity, the right to seek asylum from persecution, the right to humane treatment in detention, the right to due process, and the rights of children. (Our recommendations for rights-respecting immigration reform can be read here.)

Every day, people who call the United States home—including the mothers and fathers of US citizen children, tax-paying employees, and respected community members---are being arrested, locked up, and deported under a system that often does not even weigh their deep and longstanding ties in the balance. Our researchers have traveled to interview people who have recently been deported—or are facing potential deportation---since President Trump was elected. These are their stories.

Deported to a Country He Hasn’t Seen Since He Was Three

At 2 a.m. on August 28, guards at the federal immigration detention center in Cleburne, Texas, woke 24-year-old “Diego R,” and loaded him onto a bus full of Mexican migrants. They all sat with their wrists and ankles chained together. As the bus drove south to the border, Diego thought of his daughter, who was turning four years old that day.

“My wife bought some gifts to give her from me, so that she does not forget that she has a dad,” Diego told a Human Rights Watch researcher at a deportee reception center in Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, the day after he arrived.

The bus reached the border at noon and the migrants were left to cross the Rio Grande on a footbridge into Mexico, a country Diego had not seen since he was three years old.

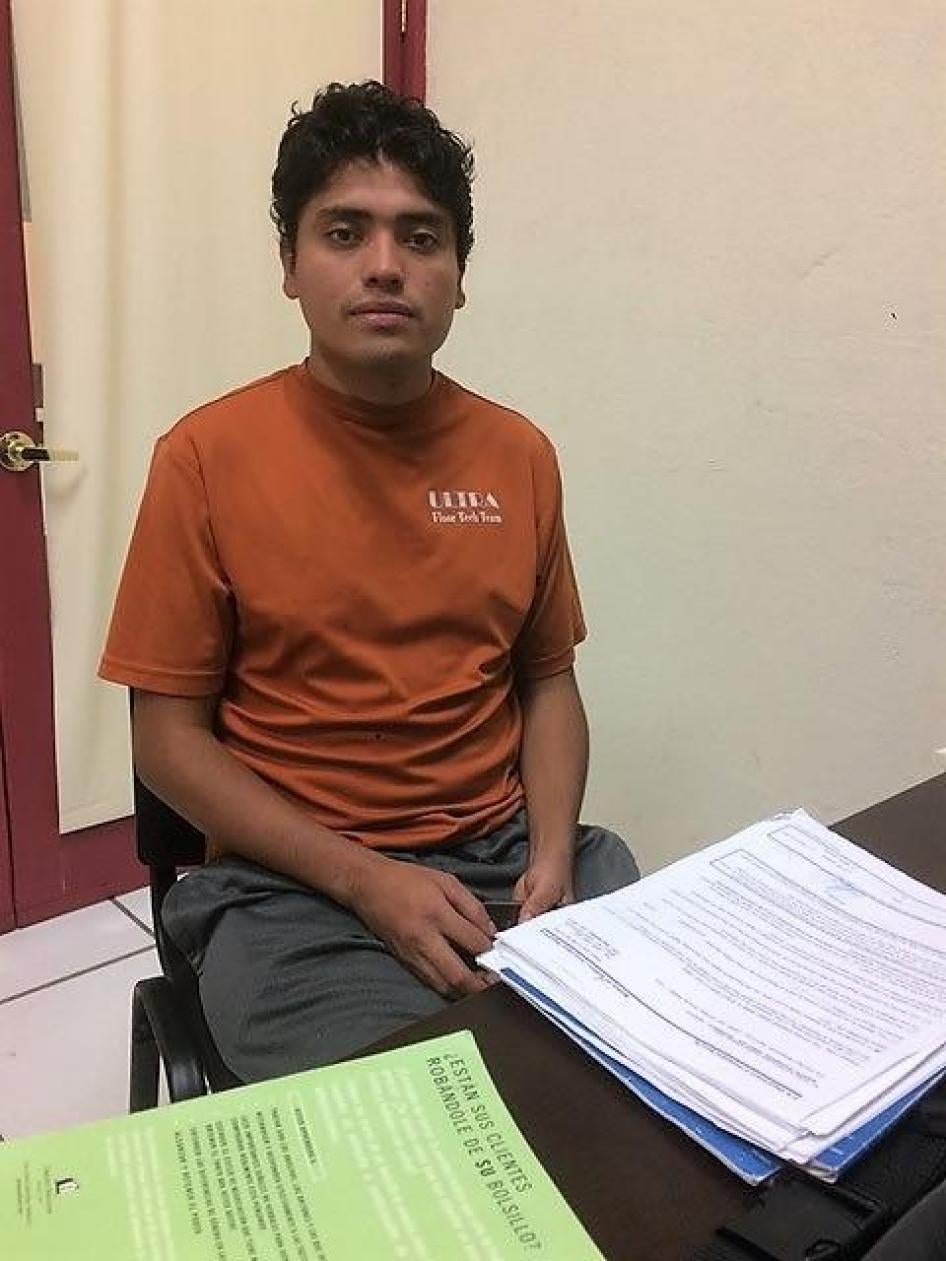

Longed to Join the Marines, but Now Deported to Mexico

Benjamin M. checked his phone constantly at the migrant reception center in Nuevo Laredo, Mexico - he had just been deported that August day, and was following the progress of his mother and wife, who were driving from Dallas to meet him.

“I have an amazing marriage and two beautiful kids,” said the 26-year-old, holding up a photo of his beaming family gathered around a birthday cake with one candle.

“Camille”, Benjamin’s US-citizen wife, would get to spend only a few hours with him in Nuevo Laredo, before returning to be with their two-year-old son and one-year-old daughter. But his mother, a legal resident of the United States, was planning to ride the bus with Benjamin to help keep him safe on the way to staying with relatives in Toluca, near Mexico City.

All of Benjamin’s seven brothers and sisters have legal status in the United States, whether as citizens or holders of visas or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrival permits, and Benjamin, the youngest, was hoping, within a year, to get legal status, as Camille’s husband.

To him, Mexico felt like a foreign country.

When Benjamin was 11, his widowed mother moved him from Toluca to Dallas to be near the older children who had emigrated. He quickly learned English to escape bullying in elementary school, he said. By middle school, “I could defend myself with words,” he said, and in high school, he found his passion: the Reserve Officers Training Corp. “It was the best experience of my life,” he said. “I was always good at school, and I would never skateboard or hang out, I was just into school and ROTC.” He served on the color guard, the rifle team, and an award-winning physical training group. His best friend, a year older, joined the Marines after graduating, and Benjamin got recruited too. He trained with the Marines during senior year, and then came the biggest disappointment of his life: without legal status, he learned, he would not be able to join.

As his friend shipped out to California and then Japan, Benjamin spiraled into depression. He doesn’t know why he didn’t apply for DACA, except that he was “so down at being rejected [from the Marines].” For the first time, he started drinking. “My mom and my brothers kept telling me to stop, that there were other ways, but I was too depressed to hear them.”

In 2013, after a cook-out at a friend’s house, he said police stopped him for driving 10 miles-an-hour over the limit on a freeway and arrested him for driving while intoxicated. He paid the $750 fine and served a two-year probation, appearing for monthly drug and alcohol tests and completing classes. It was while he was on probation that he met and married Camille, and they started their family.

Benjamin worked as a glazier, installing glass at the Cowboys’ stadium in Frisco and at other commercial sites. His mother, who lived with them, helped out at home, and they all enjoyed dinners together, outings, and going to church. But when Camille was pregnant with their daughter, Benjamin hit another rough spot. “I was working from 4 a.m. to 9 p.m., sometimes 7 days a week, and my wife was on me for not spending time with them, so I was frustrated and tired.” For the first time since his probation, Benjamin stopped by a friend’s house in July 2016, and drank a beer “then another, and another,” he said, “and there you go.” Police stopped him for driving five miles over the limit on the freeway on the way home, and arrested him for another DWI.

Probation didn’t make sense this time, he said, as ICE was by now picking up lots of people at probation check-ins. He said he knew that people who are deported with sentences that they haven’t finished serving have a hard time returning to the US legally. So he took a lawyer’s advice to do the time. After three months in Tarrant County Jail, he was transferred to ICE detention in Johnson County Jail, where he said conditions were terrible. He sighed and wiped a tear when he spoke of a Chinese friend locked up there for more than a year who had no idea when he would be released or deported. “I feel really bad for him,” he said.

But Benjamin hopes he has a chance to return legally, though under current US law, he faces a 10-year bar to applying for a visa for having lived in the US without legal status for over a year. “I don’t want anything to stand in my way,” he said. “I have to go back.”

Unfair Arrest Leads to Deportation

For 29-year-old “Alfonso B.” and his US-citizen wife, “Rebecca,” there’s a cruel irony to his deportation: the chain of events that led to it began with an argument over him needing to spend more time with the family.

Alfonso ran a cleaning company in Houston that employed 25 people. The contracts often required night work, and he was a hands-on employer. “I had to be boss, secretary, supervisor, and cleaner. With all that, it could come to 70 hours a week,” he told Human Rights Watch researchers in Nuevo Laredo on September 20, the day he was deported.

What set off his deportation troubles in 2016 was his own call to police, after Rebecca confronted him outside their apartment about the excessive hours he was working. She was speaking loudly. “I tried to pull her inside, because I knew a neighbor might get mad, and then I called the police myself, because I thought that would go better,” he said.

“It was the only thing we argued about,” Rebecca said in a telephone interview. “He would work till 3 a.m. sometimes, and then he’d need rest. But the kids wanted to go out. They wanted him to play. It got to me now and then.”

When police arrived, Rebecca said she insisted she was fine – he never hit her – and when that didn’t keep him from being arrested on a domestic violence misdemeanor charge, she wrote a letter to the court. By the time of his arrest, Alfonso had only one more step, they said, in the process of regularizing his immigration status on the grounds of his marriage to a citizen. He said his lawyer advised him there was no way to beat the charge and that the only way to put it behind him would be to plead guilty and serve the sentence – nine days – which is what he ended up doing.

Alfonso had come to the United States from Mexico City as soon as he turned 18, and quickly found work in a butcher shop. But it was his night job, cleaning several YMCAs, that he discovered he really liked. He met Rebecca when they were both cleaning at a Honda dealership, and after dating for two years, they married in 2012, and he became the sole provider. Rebecca’s daughter from a previous relationship, “Alison,” now 7, had never known a father, and Alfonso stepped into that role. “Jamie” was born in 2013, around the same time that Alfonso started his own cleaning business. His record was clean except for one drunk driving charge – and the charges that stemmed from the argument with Rebecca.

Rebecca was leaving to take Alison and Jamie to school on August 23 when immigration authorities arrived at their apartment to arrest Alfonso, initially claiming to be the police. (ICE’s practice of identifying themselves as ‘police’ has been controversial – some elected officials have objected, calling it misleading, especially where local law enforcement has been working to differentiate themselves from immigration enforcement to engender trust in immigrant communities.) Alfonso explained that the domestic violence charge was resolved, but he said the agents told him it wasn’t as far as they were concerned.

Hurricane Harvey bore down on Houston while Alfonso was in immigration detention there, and he called Rebecca constantly, she said, as she and the children made their way from their flood-prone neighborhood and rode out the storm in the relative safety of Rebecca’s mother’s home an hour from the city.

“The kids miss him,” Rebecca said, as she packed up the apartment to move with the children to Mexico City to be with Alfonso.

Rebecca is afraid of the gangs in Mexico City and believes the schools will be worse. The children, both US citizens, don’t want to leave their teachers and friends, she said. But Alfonso’s lawyer suggested that Alfonso would have a better chance at gaining legal residency in the US, Rebecca said, if he filed the papers from Mexico.

“They ask me where he is, and the little one asks why the police took him,” Rebecca says. “That’s all Jamie thinks about – that they came to the house and took him. That’s the image they have, and it breaks my heart.”

'Who Will Feed My Wife and Son?'

The day “Alejandro S.” was deported to Mexico, his first concern was for his family back home.

Alejandro, a 49-year-old snow plow operator and landscaper, hurried to the phones at the Tamaulipas Institute for Migrants in Nuevo Laredo, and called his Colombian wife, “Anna” – who is also undocumented – and his 15-year-old US-citizen son, “Daniel.”

“I told Daniel, ‘You’re the man of the house now,’” Alejandro told Human Rights Watch researchers. “But I have to get back.”

Alejandro first entered the United States in 1998, flying from Mexico City to New York on a tourist visa. He found a well-paid job with a landscaping company in Waterbury, Connecticut.

Alejandro met Anna in Connecticut. They married, rented an apartment, and had Daniel in 2002. They lived what Alejandro described as a “totally American” life. “I was earning good money,” he said. “I paid a lot of taxes.”

Little Daniel loved following his father around at work, with a child-sized rake in his hands. They both loved building snowmen and forts from the mountains of snow Alejandro would pile up in the corners of parking lots. Anna and Alejandro spoke Spanish at home, but Daniel, once he started school, would answer them in English.

In 2005, Alejandro was charged with driving without a license. Someone saw him sitting in his car in front of his brother’s house in Waterbury, Connecticut, he said, and called the police. He didn’t have a license to show the officers who pulled up – it would be another 10 years before Connecticut started issuing driver’s licenses to undocumented immigrants. That seemingly minor charge would come back to haunt him.

In 2015, a shopping mall security guard overheard Alejandro and Anna arguing in Spanish while looking for a parking space. Anna felt Alejandro was working too many hours, Alejandro remembered. The guard called the police, Alejandro said, and the officers found an open bottle of tequila in the car. Alejandro hadn’t been drinking, he said, and he passed all of the officers’ sobriety tests. But they took him to Waterbury Jail for an hour.

This is often all it takes – the briefest, most insignificant-seeming contact with law enforcement at any level can end with being handed over to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and eventual deportation.

A judge released Alejandro on $1,000 bail, he said, and for two years, his hearings kept getting postponed. At the last one, on March 23 this year, the judge ordered Alejandro to attend a three-week Alcoholics Anonymous program. The day that Alejandro was going to start, an ICE agent took him into custody.

Once in immigration custody, an immigration judge noted Alejandro’s 12-year-old driving-without-a-license charge in addition to the open-alcohol-container charge, he said, and denied him bond while awaiting deportation.

In September, after two months in detention, ICE agents manacled Alejandro’s wrists and ankles to a chain around his waist for a five-day journey by bus and plane to Laredo, Texas, where his group of deportees finally crossed the bridge into Mexico. In the migrant center, he pantomimed trying to eat with his hands chained to his waist.

Anna has left her work at a fast-food restaurant, Alejandro said, because she is afraid of showing her face in public; she is getting house-cleaning jobs when she can. Alejandro stared at his hands. “Who will feed my wife and son?” he asked.

Kidnapped by Cartels After Deportation

As in many of the country songs he loves so much, “Ricky M.’s” troubles started with a broken heart.

Ricky, who came to the United States from Mexico when he was 2 years old, says he fell into a depression after his girlfriend went off to college. He started smoking marijuana with a new set of friends. This was a change for Ricky. During his high school years, he avoided alcohol and drugs, focusing on his beloved soccer. As long as he stayed clean, his status under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrival (DACA) program was never imperiled.

In April 2015, one of his new friends gave him a few small bags of cocaine and urged him to try selling them, he said. They went into his backpack, he said, and when a Canyon Lake Park ranger smelled marijuana smoke on him and searched it, they were there, along with a marijuana cigarette.

That moment would lead to his deportation to a country he had never known, and deliver him into the hands of violent criminals. It almost cost him his life.

Speaking in September from deportee-reception center in Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, Ricky told his story to a Human Rights Watch researcher. Mexico was so unfamiliar to him, he said, that he felt like he’d been “spun off the face of the earth and set down on another planet.”

After his arrest, Ricky ended up pleading guilty to possession of marijuana and less than 14 grams (half an ounce) of cocaine “with intent to deliver,” a first-degree felony in Texas. He served 28 months of a five-year prison sentence, lost his DACA status, and was deported “for life” on August 17, 2017. Immigration agents gave him the usual red “deportee bag,” to hold the few possessions he was allowed to take with him, and he walked across the footbridge that joins Laredo, Texas, to Nuevo Laredo.

That’s when things got ugly.

Ricky caught a bus from downtown Nuevo Laredo to visit a sister in Piedras Negras, fell asleep, and was awakened with a flashlight in his eyes and a gun at his head. The gunman, who identified himself as a member of the Nuevo Laredo drug cartel, told Ricky he recognized him as a deportee by the red bag, and said the cartel in Piedras Negras would kill him if he didn’t have the right password. Then he dragged Ricky off the bus, beat him with a stick, and forced him to an apartment where six other deportees sat, terrified.

Ricky spent eight hungry days in that apartment, he said, waiting for his mother to send the cartel $3,500 – with an agreement to pay another $3,000 on Ricky’s safe arrival in San Antonio, Texas, a 144-mile, 47-hour walk from the border. Ricky didn’t want to go; he knew that he’d go back to prison for 29 months to complete his sentence, if caught, possibly spend time in immigration detention, and then be deported again for life. But the gangsters weren’t giving him a choice. To them, Ricky and the other captive deportees were cash cows.

The deportees waded the Rio Grande by moonlight with the gangsters’ guns at their backs, he said, dodged border patrol cars and helicopters in a forest for hours, moving from abandoned house to abandoned house, where other groups of captive migrants waited.

As the sun reached its peak on the first day out, Ricky’s group was abandoned by their guide, he said. They had no food and little water, he said, and they hadn’t eaten in days. One man began screaming, and Ricky found him covered in a thick layer of angry bees that detached themselves and swarmed Ricky. As the day grew hotter, Ricky ran out of water, he said, and the next thing he knew, he was being wakened by a Border Patrol officer. He had passed out by the side of a road. The officer revived him with an IV drip, he said, and – in an act for which Ricky said he will always be grateful – instead of feeding him back into the criminal justice system to complete his prison sentence, the officer drove him directly to the Laredo-Nuevo Laredo footbridge.

As Ricky told his story nearly two weeks later, his face, neck, and arms were still covered with bee-sting welts. But he managed a sad smile. “I guess I’m lucky to be alive and out of prison,” he said.

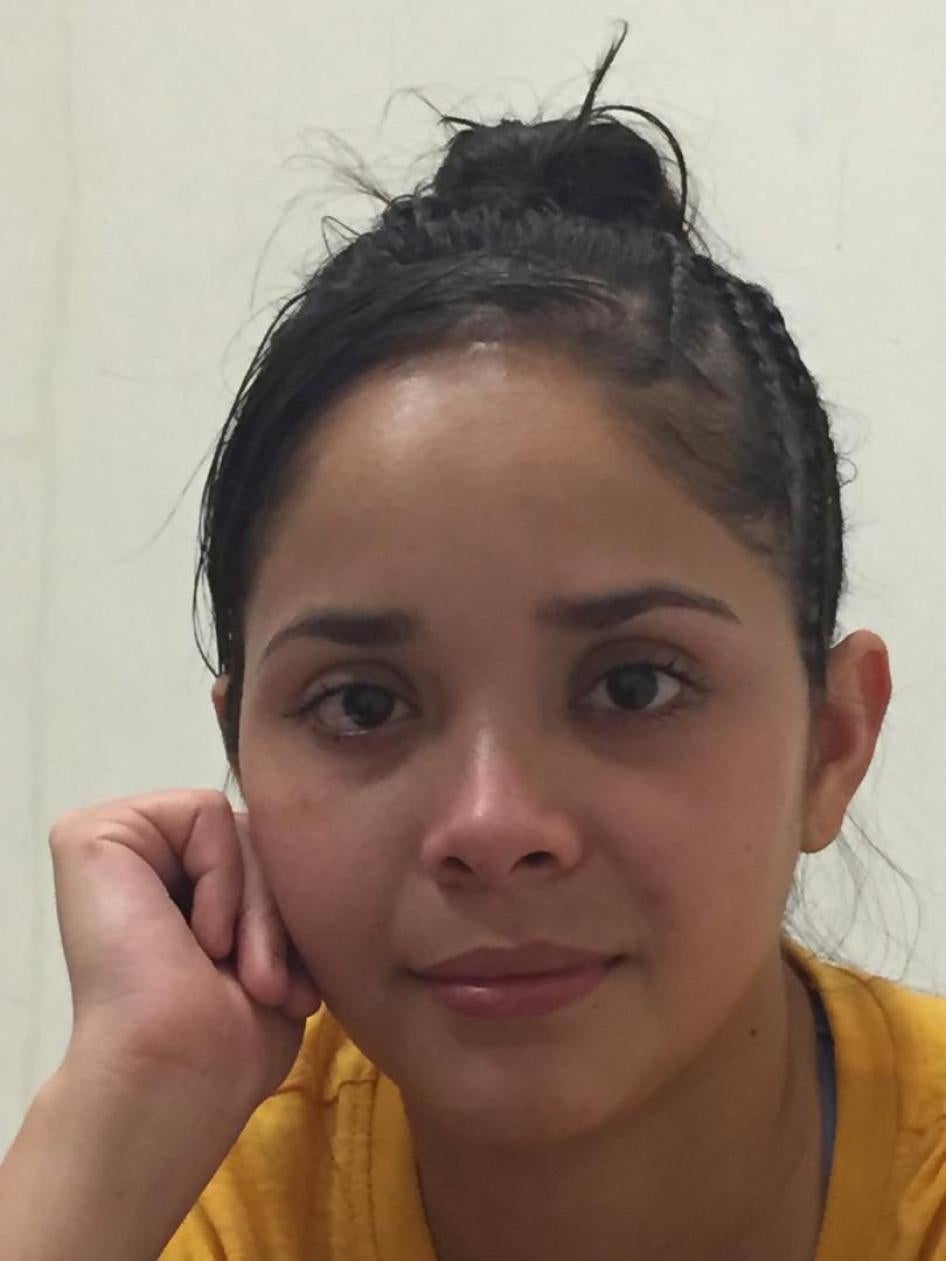

Wife and Mother of US Citizens Desperate to Return to Children

23-year-old “Adriana P.” was living in the Mexican state of Michoacán two years ago when she and her US-citizen husband, “Ricardo,” decided it was time to move to the United States. Violence among the cartels, and between the cartels and police, was becoming intolerable in their region, and they feared for their 2-year-old daughter, “Rosie,” who was born in Michoacán.

“It wasn’t so much that we wanted to earn more,” Adriana told Human Rights Watch researchers in a migrant aid center in Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, on September 1, the day of her deportation. “We needed to get away from the killings.”

Adriana, Ricardo, and Rosie each took a different route into the US. Ricardo showed his passport at a border station, Rosie crossed in an automobile with a family friend, and Adriana walked for eight days through the desert. When asked why her US citizen husband didn’t petition for her, she said, “He didn’t know how to fight on my behalf.”

They reunited in Houston, where Adriana’s father, brother, and other relatives live, and soon moved to a small town in Texas, about 200 miles away. Ricardo opened a tree-trimming business. Adriana sold home-cooked food out of her little kitchen. A second daughter, “Riley,” came along in March 2016. Life was good.

Like many immigrant families, Adriana and Ricardo opened their home now and then to friends and family members in need. In January 2017, Ricardo’s brother, “Tom,” was staying with them when police officers knocked on the door. The officers seemed to know exactly what they were after, Adriana said – and they found a small amount of marijuana in Tom’s room. Adriana was in her own room taking care of the children. Police arrested not only Tom, but Ricardo and Adriana.

Adriana served a month in jail, then spent six months in immigration detention. “I was breastfeeding Riley at the time, and it didn’t matter to them at all,” she said. Adriana signed an order of voluntary removal, but on the day she arrived in Mexico, she knew she wouldn’t stay.

“Of course I’m going back to the US,” she said. “My children are there.”

Robbed by Gangs Immediately After Deportation

It took less than 24 hours after his deportation for gang members in Mexico to find and rob “Fabio G.”

After his deportation on September 19, Fabio spent the night in a shelter before heading out, with three other deportees, to a bank on Nuevo Laredo’s central square to collect money sent by his family back in Saint Paul, Minnesota. As the deportees left the bank, a pickup came screeching to a halt in front of them, Fabio said. Two burly men jumped out, telling them to hand over their money or be kidnapped.

“We knew they had us covered with guns and probably more people around the square, so we paid,” Fabio told Human Rights Watch researchers at the Tamaulipas Institute for Migrants in Nuevo Laredo, shortly after the assault. “We were terrified. I’ve never been attacked before.” The institute, which is dedicated to protecting deportees and other migrants, stepped in to pay for Fabio’s $80 ticket to visit relatives in Jiquilpan, Michoacan.

Fabio hadn’t yet told his US-citizen wife, “Lara,” about the robbery, and she was already plenty stressed, he said, since his drunk driving arrest in March set off a cascade of immigration troubles. They had just bought a house, he said, and had lots of bills to pay, supporting his three children and her two, as well as their daughter “Mia,” all US citizens except for his oldest, who he said has temporary status under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program.

Fabio left Mexico and went to Saint Paul 14 years ago, when he was 25. He found work in all kinds of construction – roofing, siding, landscaping – and recently, he was substituting as a container loader. “I worked night and day, often 18 hours,” he said. “I’d get home, take a bath, and go to another job. On Sundays, I could go out with the family – or sleep – because I only get two hours of sleep sometimes.”

Fabio and Lara met in 2009, and within a few years, they had blended their families. Fabio’s first wife lived near them in Saint Paul, Fabio said, so that their three children, now 17, 13, and 11, could go back and forth between their parents easily. The father of Lara’s 11-year-old son and 14-year-old daughter is not in the picture, Fabio said, and they look to Fabio as their father. Mia, Fabio and Lara’s 4-year-old daughter, is the delight of the older children, he said. The videos and photos on his cell phone range from the oldest’s lavish quinceañera celebration and kids burying each other in sand at a lake beach, to Mia belting out the song “Happy.”

When Fabio was arrested in March for driving under the influence, he spent about 48 hours in Saint Paul’s Ramsey County Jail. Authorities saw that he had one earlier DUI, from eight years ago, and several tickets he had paid for driving without a license – undocumented immigrants can’t get a drivers’ license in Minnesota. They let Fabio out on a $1,200 bail, and he went back to his family – until immigration authorities arrested him at work about six weeks later. (Police in some states tip off immigration authorities when they arrest an undocumented person, so that even after local violations or charges have been cleared, immigration agents may make their own arrest.)

After 67 days in the immigration detention center in Albert Lea, Minnesota, Fabio was freed again, on May 3, on a $7,500 bond – and wearing an electronic bracelet. But on June 17, immigration authorities picked him up, he said, having revoked the bond. Three months later, they deported him.

Fabio has been in the process of arranging legal residency since 2013, he said, on the grounds of his marriage to a US citizen, and he prayed for good results from an appointment at the US consulate in Juarez, Mexico, scheduled for January. “I hope to God everything goes well,” he said, “and I’ll be able to be back with my kids in January.”

Criminally Prosecuted Multiple Times for Trying to Get Back to His Son

Forty-five-year-old “Braulio Q.” has spent more of his life in the United States than in Mexico. But after 10 months in immigration detention and his fifth deportation in September, his US-citizen son, “Miguel,” told him to wait in Mexico. Someday, his son said, there will be a way to arrange legal passage back to the US.

“I am so tired of being a prisoner,” Braulio told Human Rights Watch researchers in Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, the day after his September 30 deportation.

Braulio was 21 when he left rural Ignacio Zaragosa, Chihuahua, in 1993, and headed to the US, answering a call from a Texas rancher who needed a trainer for trick horses. “Ever since I was a kid, I loved horses and worked with them,” he said. Braulio took charge of seven horses on a ranch near El Paso, teaching them to dance, lie down, answer commands, and paw “yes” and “no.” At the ranch that same year, he met another rider, “Rosa,” a Mexican with US residency, and they eventually married; Rosa gave birth to Miguel four years later.

Braulio worked dawn to dusk, seven days a week, he said. “I never got to do anything in the city – I was always with the horses – but Rosa and Miguel would come see me at work.” By 2005, they were able to buy a house in El Paso – and three years ago, Braulio bought a property where he boarded clients’ horses.

“It was awesome, growing up with him as a dad,” said Miguel, who is now a landscaper, during a phone call from Clint, Texas. An older son of Braulio’s – born in Michoacan state in Mexico to an earlier wife – came to live with them, Miguel said, and their dad was a patient and energetic role model for both boys. “He showed us all kinds of things, not only how to work with horses, but how to build a house from top to bottom, how to do landscaping, how to save money, really how to take care of life.”

But by the time Braulio had his own horse property in 2014, he had been deported several times. In 2008, coming home from a fiesta, he was stopped by police, charged with driving while intoxicated, and deported. In 2013, he was ticketed for driving without a license – Texas doesn’t issue licenses to undocumented people – and later that same year, he got into a disagreement with his mother-in-law, who was living with him and his family.

His mother-in-law, upset, called immigration authorities, he said. According to federal records, Braulio was prosecuted for illegal reentry after deportation; he spent nine weeks in US Marshal’s custody and was deported. In 2014, he tried to cross the border, was caught and prosecuted for illegal reentry again, and sentenced to 10 months before being deported again. He managed to cross in 2015, and went back to his life in Texas, until he received notice that his ticket for driving without a license had not been resolved, as he had thought, before his 2013 deportation. When he went to clear that up, on November 14, 2016, immigration authorities arrested him.

After 10 months in detention, he was held even longer, he said, while authorities insisted that he had asked for asylum. He denied it, but the confusion took five days to clear up; he was finally allowed to sign withdrawal of a request to apply for asylum and was deported.

His plans, for the moment, were to head for Madera, Chihuahua. “I have work lined up—with cows,” he said. “I have to start somewhere.”

Miguel, now 20, married last year, and he and his wife are expecting a son. “I’m upset that I can’t have my dad here with me and my family,” he said. “I’m not going to live without seeing him. I’ll have to take off a day of work every week to visit him. It will take an hour or two to get to where he is – and crossing back – two or three hours more.”

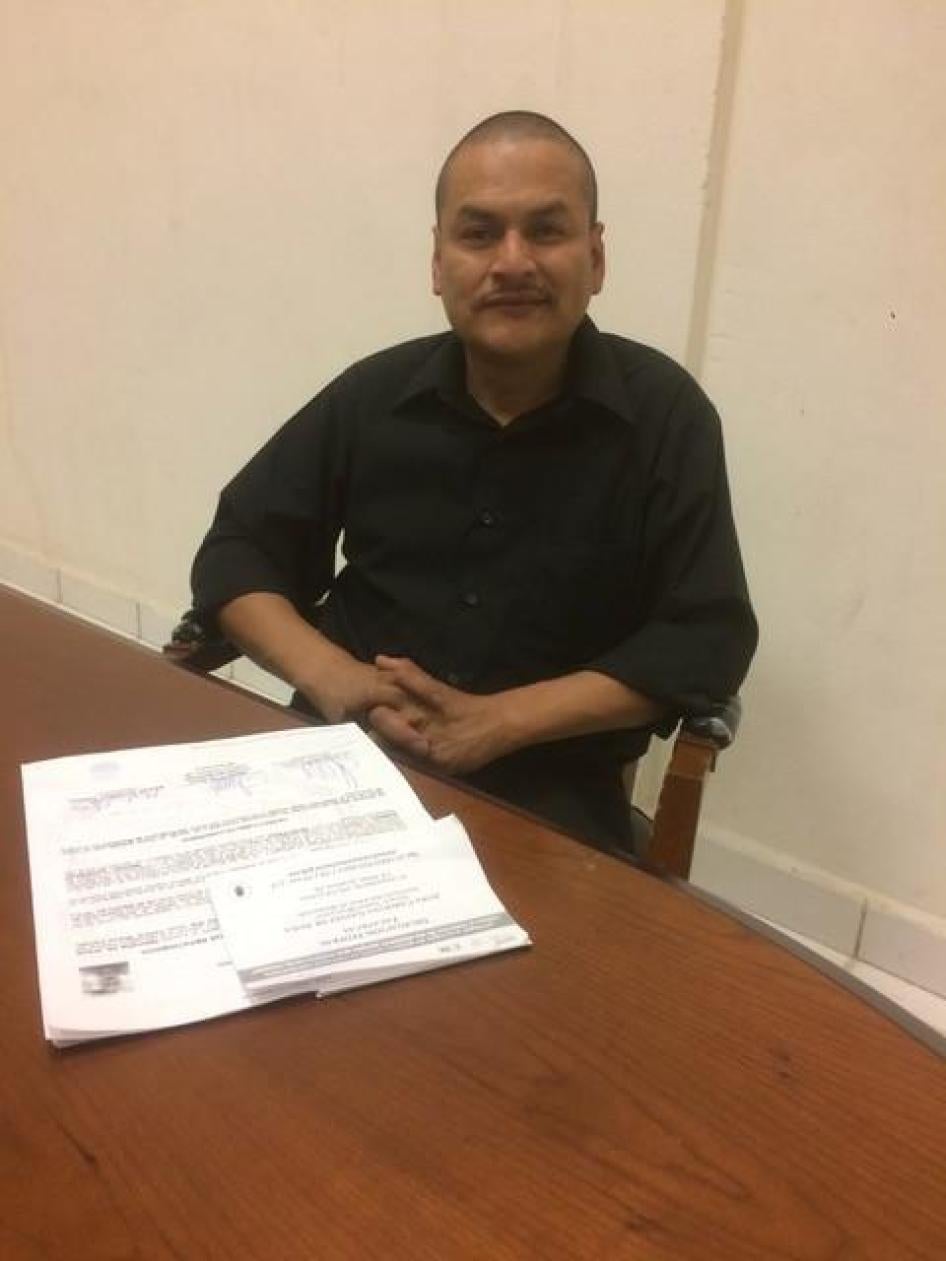

Father, Husband, and Community Leader Deported

For years, Manuel G. led a group of 25 regulars—five nights a week—for meetings of the Nueva Vida office of Alcoholics Anonymous in Tulsa, Oklahoma. This summer’s marathonica, hosted by the Tulsa AA office in mid-August, attracted 70 people from Oklahoma and surrounding states for a weekend of get-togethers that lasted into the wee hours.

Shortly past midnight on August 13, a friend asked Manuel for a ride from the marathonica to his hotel. He was stopped by police, he said, for making a made a wide U-turn. That stop led to Manuel’s deportation from the country that was his home for 29 years.

“I really like helping people who are drinking because I remember what it’s like,” he told Human Rights Watch researchers in the Tamaulipas Institute for Migrants reception center in Nuevo Laredo, Mexico. His AA co-leader, Nancy Munoz, described Manuel as a “man of faith” and praised his “passion to help others.” Manuel hasn’t had a drink in five years, he said, and he lived an orderly life in Tulsa. “I opened my own business, detailing cars, a year ago and I had just bought a trailer that my wife and I were remodeling.”

The officer who stopped Manuel during the marathonica thought Manuel had an outstanding traffic ticket, from 2005. “They were mistaken,” Manuel said. “I had paid it.” But by the time that was cleared up, he said, he had been taken into custody and was on his way to deportation.

Manuel left his small town in the state of Zacatecas, Mexico, for the United States when he was 16, and he quickly found work--cooking at restaurants in California, then moving on to Texas, for gardening work at a golf resort and eventually to join an industrial painting company. He married ”Sara,” who is also undocumented, when he was 19, and their three children were born in Texas in the 1990s. The family eventually moved to Oklahoma to be near Manuel’s parents and siblings.

In 2011, police stopped a friend’s car in which Manuel was riding, and arrested Manuel for public intoxication, he said. He served two months in Tulsa County Jail, was deported, but soon crossed the border again. That’s when he stopped drinking, he said, and Sara joined him as a leader in the AA movement, sharing her experiences as the wife of an alcoholic.

Manuel can’t help but connect the biggest tragedy of his life to the neglect associated with his years of drinking. His middle child, “Cara,” was dating a man who’d had dealings with gang members, and in 2015, when they were gunning for her boyfriend, they shot her—fatally. Sara and Manuel were just emerging from the depths of grief, focusing on their AA work and their remaining children--“Diego,” who now does bodywork on cars in Texas, and “Jessica,” who lives with them while she is saving for college—when Manuel was deported.

“I think it’s Trump,” he said. “They’re deporting people for no reason, grabbing them in restaurants and on street corners, people who’ve been in the US a long time.”

Nobody lives in the old family house in Rio Grande, Zacatecas, Manuel said, although his father, who has become a US citizen, makes occasional maintenance visits. “That’s not where I’m going today,” Manuel said, “not to a lonely, empty house. The pull is back that way,” he waved hand northward, “where everyone is.”

Caught Off Guard by Deportation

After years of looking for ways to regularize his status in the United States, Manuel C. was clearly still in shock at finding himself back in Mexico.

“The deportation notice came as a complete surprise,” he said, as he waited to use the phones in a migrant reception center in Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, after walking the pedestrian bridge across the Rio Grande with a group of deportees. “I thought everything was going well.”

Manuel left Veracruz, Mexico, in 2009, and headed to Des Moines, Iowa, where he found steady work in construction. One Sunday in 2010, he met his wife, “Amber” at church – also, coincidentally, from Veracruz. When he saw her across the room, he knew he had to talk to her. Not long after, they married; their daughter, “Daniela,” was born in 2013.

Manuel was charged with drunk driving in 2014; he said he completed a probation program. He submitted an application for asylum in the US that same year, arguing he feared violence from gang members in Veracruz. At the end of 2016, he said, a judge gave him a court date – for late 2017, which he fully intended to attend. But in the spring, his sister-in-law, who had paid his bond, received a “Notice to Obligor to Deliver Alien,” indicating that he had failed to appear for a hearing and was now slated for deportation. He thought that he must have been assigned a new hearing date, the notice for which he never saw and perhaps never received. People who miss their court hearings are often ordered deported in absentia.

On July 14, Manuel turned himself in at the immigration offices in Des Moines, and after nearly two weeks in detention, he was deported.

Amber cries every time she hears his voice on the phone, Manuel said. She is worried she won’t be able to support herself and 4-year-old Daniela on her wages as a janitor in a dentist’s office.

The story Amber told during their last phone call nearly broke Manuel’s heart: At a relative’s baby shower, the children took turns striking a piñata – one of Daniela’s favorite party games. The piñata broke, the candies scattered, and Daniela gathered up as many as her little hands could carry.

“It’s for my daddy,” she explained to Amber, “for when he comes home.”