<<previous | index | next>>

Cross-border Attacks on Civilians in Chad

Sudanese-based Janjaweed attacks into Chad

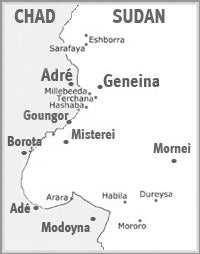

Recent Janjaweed attacks have occurred most frequently between the strategic town of Adré, thirty kilometers west of Geneina, the capital of West Darfur, and the small village of Modoyna, Chad, twenty kilometers west of the small West Darfur town of Damra. On and near this part of the border the civilian population is predominantly Masalit in the north and Dajo in the south, both non-Arab cross-border tribes that have also been the targets of Janjaweed attacks in Darfur.

Janjaweed militias based in Darfur were crossing the border north of Adré as early as 2003, largely in Zaghawa areas. They began conducting occasional raids in the region south of Adré in 2004. The border situation generally improved in 2005 thanks to a tentative ceasefire in Darfur; increasing presence of the AMIS (mandated by the Darfurian rebels and the Sudanese government to monitor an April 2004 ceasefire and protect civilians) in Darfur and in the border town of Tine (in a Zaghawa area) and in Abéché; and regular Chadian army patrols along the border. However, subsequent to the October-December 2005 withdrawal of the Chadian army from the area, and especially since the December 18 attack on Adré, security has deteriorated dramatically, and militia activity has increased. According to the secretary general of Adré prefecture, Janjaweed militias have attacked more than fifty border villages in the prefecture since December 18.16 Testimony from dozens of eyewitnesses suggests that starting in mid-December, Janjaweed raiding parties originating in Sudan have been carrying out attacks against villages inside Chad on a regular if not daily basis.

As markets in Darfur have been disrupted by violence and population dislocation, normal commerce is being replaced by a war economy in which livestock raiding and looting feature prominantly. Hence Janjaweed cross-border raids appear to be motivated heavily by considerations of profit, as cattle, horses, food and even household items such as straw mats and cups have been looted. Chadian villagers who resist robbery are summarily shot, and in some instances the Janjaweed have wantonly fired into huts, injuring and killing those inside. A thirty-five-year-old Dajo woman recounted an early morning Janjaweed attack on her village in September 2005 that killed seven, including her husband and her sixteen-year-old son. She was wounded, and was subsequently evacuated to the hospital in Adré, where her right leg was amputated at the knee:

I was sleeping and then I heard the guns and the screaming. I got up and my son was bleeding. I ran to him and I saw that he was dead. I ran back and that was when I was shot. . . . I just saw blood. My husband went into his room to get his grigri17 and the bullet hit him in the stomach and came out of his back. They had never attacked us before.18

Statements attributed to Janjaweed by eyewitnesses suggest that the appropriation of land may be another motivation for the violence. A fifty-one-year-old Dajo farmer from a Chadian border village that was attacked on December 18, 2005, is one of many who believe the Janjaweed seek to push non-Arabs off their land:

They came in the morning and they took the cows and the goats and they said, “What are you doing on this land. This is not your land. These cows are not your cows anymore. If you stay you will be killed, but if you run we won’t kill you.” The Janjaweed want to empty this place. They want to recover the land of the Nuba.19

Approximately one hundred kilometers south of Adré, in the vicinity of Borota (which is predominantly Masalit-inhabited), Janjaweed attacked a few hamlets on the night of January 20, 2006, while Human Rights Watch researchers were a few kilometers away in Borota center, documenting earlier attacks.20 The Janjaweed shot and badly wounded one man from Oussouri hamlet in the stomach; they also stole several horses.

Approximately 200 kilometers south of Adré, the village of Koloy has become a major center for internally displaced Chadians. Many villagers decided to relocate to Koloy, which lies twenty kilometers from the Sudan border, following a major Janjaweed attack in and around the village of Modoyna on September 27, 2005, that claimed dozens of lives.21 The Chadian army responded aggressively to that attack, engaging Janjaweed forces in a running gunbattle that ended near the border, and taking eight captives. One captive reportedly died of his wounds and the other seven are reported to be awaiting trial in a closed tribunal in N’Djamena.22

Human Rights Watch interviewed numerous victims of an attack against villages in the same area on December 18, 2005.23 That episode catalyzed an exodus away from the border and into Koloy that dwarfed the September displacement (see also below, “Humanitarian Consequences in Chad of Cross-Border Violence”).

Displaced persons in Koloy, most of them Dajo, described a pattern of Janjaweed attacks remarkably consistent with testimony recorded further north, where the Masalit predominate: light skinned Arabs and some black Arabs wearing Sudanese army khakis and turbans carried out attacks on villages, usually on horses and sometimes on camels. Some witnesses remembered seeing “white” (light colored) desert camouflage uniforms in addition to “khaki Sudanese.” Some in Koloy said they saw rank and insignia on the attackers’ uniforms. Eyewitnesses gave Human Rights Watch names of Chadian Arabs they recognized from their villages who had evidently joined the Janjaweed.24 A forty-eight-year-old man with scars from a bullet that passed through his shoulder said he was wounded near the border on December 18, 2005, by an assailant who identified himself as Janjaweed.

I saw soldiers in uniforms in the fields so I went to greet them. One of them said, “Wrong. You think we’re the Chadian army. How do you know we’re from Chad?” He said ”Have you heard of the Janjaweed?” I said ”I don’t know.” Then he said, “Okay, run.” I’m not a thief, why should I run? But I ran. Then he said, “Hey!” I turned around. He shot me.25

As a result of the security vacuum that exists on the Chad-Sudan border, Janjaweed raids have grown increasingly brazen. The Chadian military confirmed a Janjaweed attack on January 10, 2006, in Dorote, a Dajo village between Adé and Goz Beida, more than forty kilometers inside Chadian territory.26

In the absence of the Chadian military south of Adré, many villages have organized self-defense groups to discourage and defend against Janjaweed attacks—as their counterparts in Darfur were forced to do years earlier. These groups, made up of men and boys, are armed mostly with spears, ceremonial knives and swords, bows and arrows, carved clubs and boomerangs, though in some places villagers have raised money to equip their self-defense forces with firearms, generally Kalashnikov assault rifles.

Human Rights Watch noted a well-armed and well-organized self-defense group in Modoyna (comprised mostly of Dajo and some Zaghawa). The self-defense group in Borota, mostly Masalit, is said to have possessed around fifty firearms.27 Officially, the Chadian government has refused to arm civilians for its own reasons, and now aware of how quickly this strategy has spun out of control—by accident or by design—in Darfur. However, these civilian militia groups have been growing along the border south of Adré with or without outside assistance since at least 2004, when Human Rights Watch noted the presence of militia groups from inside Chad as well as militia groups composed of refugees on both sides of the border.28

Ethnic targeting by Janjaweed and others

The area of Chad bordering Darfur has a population that, similar to Darfur, is ethnically varied, with Arab groups present as well as non-Arabs (Africans). Many ethnic groups live on both sides of the border. Recent cross-border violence into Chad shows persistent signs of ethnic bias as it has largely affected two non-Arab tribes: the Masalit and the Dajo, which reside on both sides of the Chad-Sudan border and have been subjected to Janjaweed attacks in Darfur.29

The vast majority of eyewitnesses to Janjaweed raids in eastern Chad described their attackers as Arabs from Sudan with light or “red” skin color, speaking Sudanese Arabic. Many victims said their attackers used the pejorative racial epithet Nuba, suggesting that ethnic animus directs the violence. In border areas where non-Arab villages have been abandoned due to incessant raids, Arab villages enjoy de facto immunity from attack. The Janjaweed are drawn heavily from landless and often impoverished nomadic Arab tribes in Darfur, many of which emigrated from Chad in previous decades and have family ties on both sides of the border.

Recent Janjaweed attacks in eastern Chad are taking place in the context of underlying ethnic tensions that the Janjaweed raids only exacerbate. Inter-tribal violence in the eastern Ouaddaï province of Chad, especially in the area between the main towns of Adé and Goz Beida, has claimed at least twenty-two lives since the beginning of 2006.30 Disputes over resources and pastoral land use have led to bloodshed between the Dajo, which make up the majority in the area, and both Arab and other non-Arab tribes (who include the Mimi and the Waddai, both informally allied with the Arabs). Fields and orchards have been burned, and one village Human Rights Watch visited, Routrout, has been abandoned due to the continuing violence. The sultan of Goz Beida called all village chiefs in the area to a meeting on January 30 in a plea for peace.

Furthermore, Chadian Arabs from the area south of Adré have recently been crossing into Sudan in numbers significant enough to raise concern among humanitarian workers that the migration is being driven by fear of retaliatory attacks at the hands of non-Arabs.31 The motive behind the 2004 murders of two Arabs south of Adré by Massalit attackers was thought to have been revenge for Janjaweed raids in the area.32

Janjaweed leadership implicated in attacks in Chad

Two well-known Janjaweed militia leaders known to be closely allied to the Sudanese government are likely among those responsible for the violence in the area south of Adré. Hamid Dawai and Abdullah abu Shineibat were among the seven Janjaweed militia leaders named, by the United States (U.S.) Department of State in 200433 and in reports by Human Rights Watch and others,34 as leaders of some of the most abusive Janjaweed forces in West Darfur.

Victims of violence in Koloy identify Hamid Dawai, an emir of the Beni Halba tribe and Janjaweed leader in the Terbeba-Arara-Beida triangle of West Darfur, as being behind attacks on their villages. Dawai is said to be a Chadian Arab who is a naturalized Sudanese citizen. His considerable influence on the Janjaweed in Chad was demonstrated when he averted an imminent Janjaweed attack on a village north of Koloy, Chad, as a Dajo official from that village recalled:

The Janjaweed came at eight o’clock in the morning and circled the village. At ten o’clock Hamid Dawai came in two vehicles. I knew it was him because he said, “I am Hamid Dawai.” He said, “Where is the chief?” I said, “It’s me; I am the chief.” I brought water and gave him tea. He spoke with the Janjaweed and said that they would not attack my village.35

Another man, whose father was killed in a Janjaweed raid between Goz Beida and Adé, told Human Rights Watch that Dawai seized fifty-one cows from the Janjaweed responsible and had them returned by way of Ali Muhammad Saleh, the deputy under-prefect of Adé.36 In Goz Beida, Chadian civilian officials have been negotiating directly with Dawai in 2006 in an attempt to put a stop to Janjaweed cross-border attacks.37

Abdullah Abu Shineibat, also an emir from the Beni Halba tribe, is the commander responsible for Janjaweed attacks in the area of Modoyna, twenty kilometers east of Koloy, according to eyewitnesses. Abdullah Abu Shineibat is reported to have an area of operations in Sudan that stretches from Arara (close to the Chadian border) some thirty kilometers east towards Habila, with a headquarters in Amsamgamti. Villagers in Modoyna believe their looted cattle can be found in Amsamgamti. Both Arara and Habila are frequently mentioned as points of origin in Sudan for Janjaweed raiding parties, as is Gobe, Sudan, due east of the Chadian village of Hadjer Beida.38

Sources inside the Chadian military identify Yacub Angar as the Janjaweed commander whose influence reaches as far south in Sudan as Hagar Banga, near the Chadian town of Tissi.39

Sudanese government participation and complicity in cross-border attacks

The links between the Sudanese government and the Janjaweed militias in operations in Darfur have been comprehensively documented over the past few years.40 Human Rights Watch found evidence of apparent Sudanese government involvement in attacks against civilian populations in eastern Chad since early December 2005. Witness accounts and physical evidence indicated that government of Sudan troops and helicopter gunships participated directly in attacks, while many people reported seeing Antonov aircraft approach from Sudan, circle overhead, then return to Sudan in advance of Janjaweed raids; they believe spotters in these aircraft report concentrations of cattle to forces on the ground.41

Human Rights Watch documented four attacks by armed forces based in Darfur between December 5 and 11, 2005, in the prefecture of Goungour, with more than 8,300 mostly Masalit inhabitants in fifty-one hamlets, located eighty kilometers south of Adré. The first two attacks reportedly involved Janjaweed militias backed by government of Sudan soldiers and vehicles and two attack helicopters, which rocketed several areas over a three-day period.

Villagers described how they initially believed that Sudanese forces were pursuing Sudanese SLA rebels who were fleeing across the border into Goungour after skirmishes in Darfur. But it became apparent that civilians were the targets, as government of Sudan soldiers and Janjaweed directly attacked twenty-two villages in the Goungour area. Local officials in Goungour told Human Rights Watch that a total of forty-five people were killed over seven days of bloodshed, though only two fatalities could be verified.42 Livestock and food in large quantities were reported stolen.

In Bakou, part of Goungour prefecture, Human Rights Watch collected fragments of air-to-ground rockets43 and examined other physical evidence of aerial assaults presented by villagers, including shrapnel, stabilizing fins, a partially exploded rocket and handfuls of flechettes—small metal darts that are dispersed by anti-personnel ordnance.

Janjaweed militias between December 16, 2005, and January 5, 2006, attacked, looted and emptied forty villages out of eighty-five in the mostly Masalit prefecture of Borota, one hundred kilometers south of Adré. These attacks were conducted in the company of Sudanese police and soldiers, according to witnesses, who recognized the Sudanese officials not by their uniforms (they were dressed like Janjaweed, with assorted uniforms and turbans), but by their faces—they said they knew them from trading in Sudan, the border being within a few kilometers of several Borota villages. Reportedly the Janjaweed/Sudanese officials killed twelve Chadian civilians and wounded six, and looted horses, cattle, bags of grain and other goods. The inhabitants of all forty villages attacked in this period subsequently abandoned their homes and took refuge in Borota center.44

Hamid Dawai, one of the Janjaweed leaders mentioned above, is based in Beida, Sudan, where the government of Sudan reportedly maintains a sizable military base that has been reinforced recently with helicopters and heavy weapons, including tanks.45 In spite of the presence of these military assets, Sudan has proved unable or unwilling to prevent its Janjaweed militas in the area from launching attacks into Chad.46

Janjaweed-Chadian rebel coordination

Human Rights Watch found evidence of coordination between Janjaweed militias and RDL rebels, and there is circumstantial and other evidence that not just the Janjaweed but the RDL receive material and other support from Sudanese government forces. RDL rebels have several bases in West Darfur around Geneina, where Janjaweed militias and RDL rebels are said to occupy nearly adjacent camps (and where the Sudanese government has a substantial military presence),47 and in southern West Darfur. They have also reportedly been spotted in West Darfur in the company of government of Sudan army-sponsored Popular Defense Force militias.48

Eyewitness testimony suggests a military intelligence link between RDL rebels and Janjaweed militias. Local officials report RDL forces visited Modoyna on December 16, 2005, and spent the night there peacefully. When the RDL left Modoyna on December 17, an RDL rebel warned a member of the local self defense force that the Janjaweed planned a raid against Modoyna for the next day. 49 As predicted, a Janjaweed militia attacked Modoyna the next day, December 18.50

A coordinated RDL-Janjaweed attack took place on December 16, 2005, in Borota. The RDL rebels, who wore red bandanas marked with the letters “RDL” and drove vehicles bearing the same marking, controlled Borota for two hours before withdrawing. The same night Janjaweed militias raided six villages in the vicinity.51

[16] One humanitarian relief group estimates that twenty-six to twenty-eight villages in the area have been attacked or destroyed by Janjaweed during the same period. Human Rights Watch interview, Chad, January 13, 2006.

[17] Small leather amulets containing quotes from the Koran, believed to protect the wearer from harm. They are known as hijab on the Sudanese side of the border.

[18] Human Rights Watch interview, Chad, January 27, 2006.

[19] Human Rights Watch interview, Chad, January 27, 2006. Nuba is a pejorative term for black people and/or slaves that is used in Sudan, usually by non-Africans.

[20] The hamlets included Yayulata, Oussouri, and Ishbara. The earlier attacks in the Borota area occurred between December 16 and January 6.

[21] Local sources place the death toll at anywhere from fifty-three to seventy-two civilians killed; most media reports count thirty-six dead—see for example “Chad: Government says Sudanese insurgents killed 36 herders in east,” IRIN, September 27, 2005, [online] http://www.reliefweb.int/rw/rwb.nsf/db900SID/KKEE-6GMS5S?OpenDocument&rc=1&cc=tcd.

[22] The torture and other mistreatment of prisoners is a serious problem in Chadian detention centers, so the status of these detainees must be monitored. Human Rights Watch has heard recent testimony from a Darfurian political activist who was held incommunicado and tortured in the Chadian capital in 2005. Human Rights Watch interview, Abuja, Nigeria, December 15, 2005.

[23] Human Rights Watch interviews, Chad, January 27-28, 2006.

[24]Chadian Arabs were recognized among Janjaweed attackers in other incidents. For example, many villagers from Borota villages told Human Rights Watch that they grew up with two Chadian Arabs who joined the Janjaweed and returned to participate in attacks in Borota. Their names, provided to Human Rights Watch, were apparently well-known to many residents. Villagers displaced from the Koumou area approximately 100 kilometers southeast of Borota similarly provided names of other Chadian Arabs they knew who apparently joined the Janjaweed.

[25] Human Rights Watch interview, Chad, January 27, 2006.

[26] Human Rights Watch interview, Chad, January 31, 2006.

[27] Human Rights Watch, interview, Chad, February 3, 2006.

[28] See Human Rights Watch Report, “Empty Promises?”

[29] In Chad, the Masalit make up the majority between Adré, located twenty-five kilometers west of the Sudanese town of Geneina, and Adé, 175 kilometers to the south. The Dajo predominate in the area to the south and east of Adé.

[30] Human Rights Watch interviews, January 29 to February 1, 2006. Goz Beida (forty kilometers from the Sudanese border) is seventy-five kilometers southwest of Ade.

[31] Human Rights Watch interview, Chad, January 31, 2006.

[32] See Human Rights Watch Report, “Darfur in Flames.”

[33] “Confronting, Ending, and Preventing War Crimes in Africa,” Pierre-Richard Prosper, Ambassador-at-Large for War Crimes Issues, Testimony before the House International Relations Committee, Subcommittee on Africa, Washington, DC, June 24, 2004, [online] http://www.state.gov/s/wci/rm/33934.htm.

[34] See Human Rights Watch Report, “Darfur Destroyed.”

[35] Human Rights Watch interview, Chad, January 27, 2006.

[36] Human Rights Watch interview, Chad, January 26, 2006.

[37] Human Rights Watch interviews, January 25-30, 2006.

[38] Human Rights Watch interviews, Chad, January 28, 2006.

[39] Confidential communication to Human Rights Watch, Chad, January 31, 2006.

[40] See Human Rights Watch Report, “Entrenching Impunity.”

[41] Human Rights Watch interview, January 29, 2006.

[42] Medical records examined by Human Rights Watch at the dispensary in Goungour showed fifteen civilians injured in Goungour on December 11 and two killed. All casualties resulted from gunshot wounds.

[43] Some rocket fragments bore Cyrillic letters similarly to fragments recovered by Human Rights Watch in 2005 from Sudanese government attacks near Jebel Mara in Darfur.

[44] Human Rights Watch interview, Chad, January 20, 2006.

[45] Human Rights Watch interview with Chadian officials (identities withheld), Chad, January 20, 2006;

“SUDAN-CHAD: Cross-border conflict escalates,” IRIN, March 16, 2004, [online] http://www.reliefweb.int/rw/rwb.nsf/db900SID/OCHA-64D58K?OpenDocument&rc=1&cc=tcd.

[46] See Human Rights Watch Report, “Darfur Destroyed,” for further details on Hamid Dawai’s involvement in the attacks in the Beida area in 2003 and 2004.

[47] A video reportedly aired late last year on Al Jazeera Television showed RDL leader Muhammad Nour parading new weapons and vehicles, in the company of a mid-level Janjaweed commander. Human Rights Watch interviews, Chad, February 3, 2006.

[48] Confidential communication, February 6, 2006.

[49] The RDL rebel warned that the people of Modoyna should bring their cattle in from the fields, because the Janjaweed planned a raid for the next day. Human Rights Watch interview, Chad, January 29, 2006.

[50] Human Rights Watch interview, Chad, January 29, 2006.

[51] The French army (which patrols the Darfur/Sudan border at Chadian government request) arrived in Borota a few hours later. The next day, French soldiers reportedly allowed RDL rebels to drive through Borota on their way to Adré, which the rebels attacked the following day. Human Rights Watch interview, administrative district official, Borota, Chad, January 20, 2006.

| <<previous | index | next>> | February 2006 |