Civilian Harm

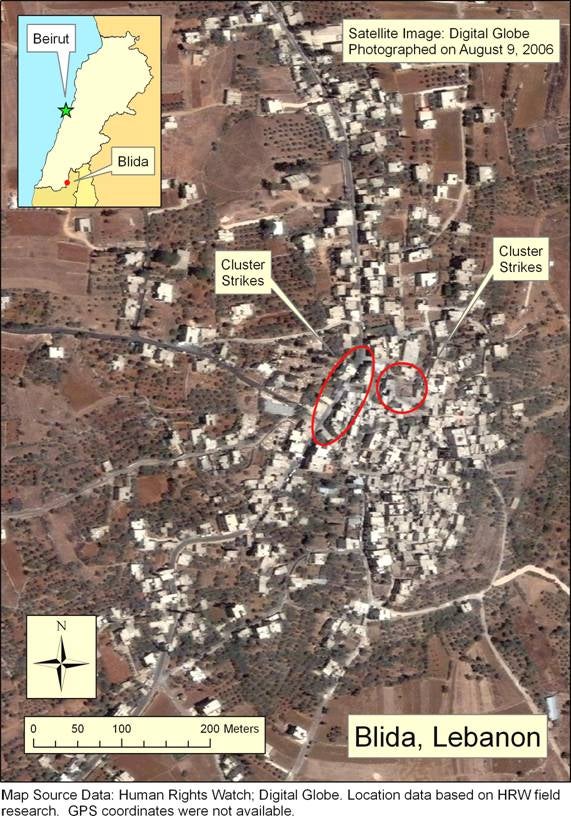

Cluster munitions have taken and continue to take a deadly toll on the civilian population of south Lebanon. The fatal results of cluster munitions began with the first strikes, including an attack on the village of Blida on July 19, 2006, where one civilian was killed and at least 12 wounded by a single cluster munition strike.141 However, by the time of Israel’s maximum use of the munitions over the final three days of the conflict, civilians had either fled south Lebanon or were under shelter, so the greatest civilian harm has come from the duds left behind, which continue to plague daily life in south Lebanon. As of January 2008, cluster munitions had caused close to 200 civilian casualties after the conflict.142 Children face an especially acute threat; MACC SL reported at that time that 61 of 192 casualties were under 18 years old. At least 42 civilian and military deminers had suffered deaths and injuries.143

Civilians returning home after the ceasefire found unexploded cluster submunitions in homes, neighborhood streets, and fields. “The problem is getting so big that we can’t face it,” said an officer with the Lebanese Army’s National Demining Office, speaking in October 2006.144 Given the sheer number of cluster duds on the ground, casualties are unavoidable, but most injuries and deaths fall into one of several definable categories: (1) civilians cleaning up the rubble of their war-torn homes and fields; (2) children playing with the curiosity-provoking submunitions; (3) farmers trying to harvest their crops; (4) civilians simply moving about villages as part of everyday life; and (5) professionals and civilians clearing submunitions.

Time of Attack Casualties

Though Human Rights Watch has documented several strike casualties, the precise number of injuries during the war is not known. Many civilians evacuated their homes before the barrage of cluster munitions fell during the final three days of the war. Frequently, the only villagers remaining in town were the elderly and infirm, who took shelter in their homes to avoid the weapons raining from the sky. When civilians returned home, they could not necessarily differentiate fatalities as a result of cluster munitions from casualties due to fighting, shelling, or other artillery fire.

On July 19, at around 3 p.m., the IDF fired several artillery-launched cluster munitions on the southern town of Blida, resulting in more than a dozen casualties. The cluster attack killed 60-year-old Maryam Ibrahim inside her home. At least two submunitions from the attack entered her basement, which the `Ali family was using as a shelter, wounding 12 persons, including seven children. Ahmed `Ali, a 45-year-old taxi driver and head of the family, lost both legs from injuries caused by the submunitions. Five of his children suffered injuries: Mira, 16; Fatima, 12; `Ali, 10; Aya, 3; and `Ola, 1. His wife, Akram Ibrahim, 35, and his mother-in-law, `Ola Musa, 80, were also wounded. The strike injured four other relatives, all German-Lebanese dual nationals sheltering with the family: Muhammad Ibrahim, 45; his wife, Fatima, 40; and their children `Ali, 16, and Rula, 13. On July 24, 2006, Human Rights Watch broke the news of the use of cluster munitions in Lebanon by the IDF.145

Returning Home after the Ceasefire

Civilians reported a significant number of casualties in the days immediately after the end of the war, as families returned home and began to clear the rubble of the villages. Shattered homes, concrete piles, and other signs of destruction easily hid the small submunitions. “I didn’t have any idea of the cluster bombs,” Ahmed Mouzamer, the vice head of Sawane municipality, told Human Rights Watch.146 Many civilians were exposed to submunition duds without any knowledge of the dangers or even the presence of the submunitions.

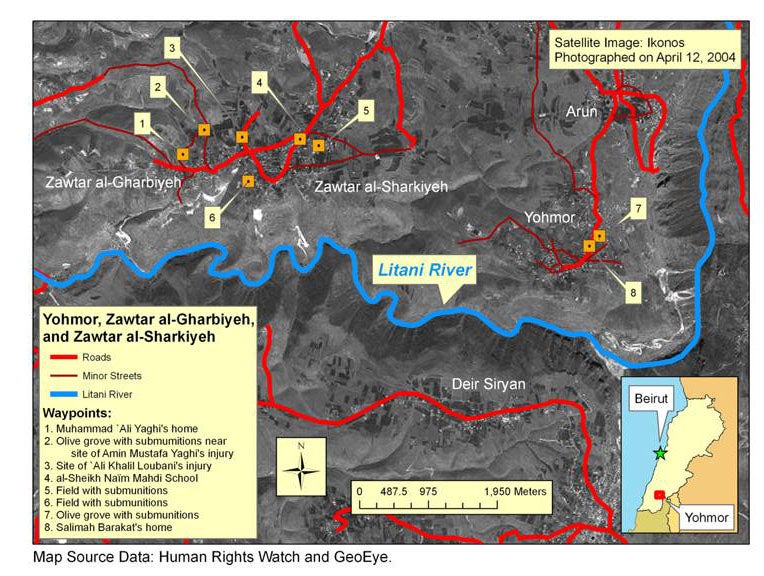

Salimah Barakat, a 65-year-old tobacco farmer in Yohmor, stayed in her home during the war to care for her disabled son and daughter. She told Human Rights Watch that she heard cluster munitions falling throughout the night during the last four to five days of the war, though she received no warning of an impending attack. When the ceasefire commenced on August 14, Barakat finally emerged from hiding to begin clearing the path to her home, trying to remove the large rocks so her blind daughter could safely walk around the house. She remembers moving a large rock blocking the stairs down to her home when a submunition exploded; she later learned that she had accidentally hit an unexploded dud. The explosion sent her to the hospital for shrapnel wounds to her chest, lower abdomen, and right arm. She has returned to work in her tobacco field and olive groves, which as of October 2006 remained littered with cluster submunitions.147 During its visit, Human Rights Watch found an M77 submunition and several ribbons in the backyard of her downtown home.

Unlike Barakat, the Hattab family left during the war, returning to their home in the center of Habboush at 9:30 a.m. on August 14. Musa Hussein Hattab, 33, and several family members began to clean the space adjacent to his house when Musa picked up a submunition that exploded, killing him and his 13-year-old-nephew, Hedi Muhammad Hattab. The blast injured four other family members, including `Ali Hattab, 46, who remained in the hospital until late October, and his brother Ibrahim Hattab, 38, who had three operations to repair his right leg.148 The doctors estimated it would be another year before Ibrahim Hattab would be able to resume work.

MACC SL reported 45 civilian casualties like these in the first week following the ceasefire, as civilians returned home.149 Simple efforts to rebuild and construct a home, however, continued to threaten civilians even after late August. On September 12, with clearance efforts well underway, Raghda Idriss returned home and began removing the rubble that fell into her olive grove next to her home on the outskirts of Bar`achit.150 In the course of her cleaning, she tossed a rock aside that hit a submunition causing it to explode. Idriss suffered injuries to her right arm, sending her to the hospital for a week. She now must live with her daughter to get the care she needs for recovery.

Children

Of MACC SL’s 192 reported civilian casualties, about 32 percent were under the age of 18.151 Children frequently grab submunitions out of curiosity, attracted by the ribbon or the weapon’s unusual shape and size. Several also reported that they thought the submunition resembled a soda can or, in one case, a perfume bottle. The submunitions “look like a toy,” said `Ali Fakih, the mukhtar of Kfar Dounine.152

Thirteen-year-old Hassan Hussein Hamadi was undergoing treatment in London when Human Rights Watch visited. Hassan’s friend `Ali Hussein Dabbouk recounted that on August 27, in Deir Qanoun Ras al-`Ein:

Hassan and a few of us were playing hide-and-seek next to the house. When Hassan went to hide, he found a cluster bomb, and he thought it had already exploded. So he brought it with him. It was black with the white ribbon completely burned. From the inside, there was red stuff. He brought it back to the house. When he was alone, he threw it and it exploded.153

Hassan’s 19-year-old sister, Fatima Hussein Hamadi, said he lost his right thumb, part of three fingers on his right hand, and flesh on his right arm. He suffered shrapnel wounds to his stomach and neck, and doctors had to operate on his right shoulder.154

Marwa `Ali Mar`i, 12, recovers in the Jabal Amel Hospital, Tyre, with her mother on August 16, 2006. Marwa picked up a dud submunition in the town of `Aita al-Cha`b and it exploded. She was severely injured in the blast along with two other children. © 2006 Marc Garlasco/Human Rights Watch

Clusters intrigued other children, such as Sukna Ahmed Mar`i, 12, and her two cousins Marwa `Ali Mar`i, 12, and Hassan Hussein Tahini, 11, all from `Aita al-Cha`b. According to the children, with whom Human Rights Watch spoke in Tyre’s Jabal Amel Hospital, the three were exploring a site where fighting had taken place during the war. As the children walked through the town, Marwa picked up a small cylindrical object she described as “like a Pepsi can but smaller.”155 She threw it to the ground, causing it to explode. Hassan said, “My stomach was pulled out. All three of us were injured, but I was injured most. Noise was coming out of my stomach. My hand and my stomach hurt me the most.”156

Dr. `Abdel Nasser Farran told Human Rights Watch that Hassan was suffering from a shrapnel wound caused by a piece that entered at the waist and exited through the stomach.157 It shredded his intestines and damaged his liver and stomach. He was in critical condition when Human Rights Watch saw him. Sukna had shrapnel injuries to her liver and other light wounds to her body. Marwa had minor leg injuries and was released from the hospital a few days later.

In late August, Human Rights Watch researchers returned to Blida, which Israel attacked with clusters on July 19. `Abbas Yousif `Abbas, a 6-year-old boy, was injured on August 30, suffering shrapnel wounds to the stomach, bladder, left lung, and right hand. He said that he was on the road in front of a friend’s house when another friend picked up a submunition and threw it, and it exploded. “It looked like a perfume bottle,” he said.158

Despite education efforts, many children remained unaware of the danger of submunitions into the fall of 2006. In Halta, Rami `Ali Hassan Shebli, 12, died on October 22 when he picked up a submunition while playing with his brother, Khodr, 14. Khodr, who suffered shrapnel wounds as a result of the incident, sat on a tree branch outside of his neighbor’s home, dropping pinecones on his brother on the ground below. Rami picked up something to throw back at his brother. When a witness noticed that Rami had picked up a submunition and yelled at him to put it down, Rami raised his hand to throw it away. The dud exploded when his hand was behind his ear.159 Human Rights Watch arrived in Halta several hours after the incident and saw the Lebanese Army destroy about 15 unexploded cluster duds in a backyard next to the village in the course of an hour.

Two men collect the final remains of 12-year-old Rami `Ali Hassan Shebli, who was killed by a DPICM submunition in Halta on October 22, 2006. Rami unwittingly picked up the submunition while playing with his brother only a couple hours before this picture was taken. © 2006 Bonnie Docherty/Human Rights Watch

Agriculture

Perhaps the most dangerous threat to civilian safety came as farmers and shepherds resumed the agricultural activities that characterize much of south Lebanon’s economy. Unexploded cluster duds blanketed the fields of south Lebanon, transforming olive and citrus groves and tobacco fields into de facto minefields. “Cluster bombs are causing great, great problems because they fell in all the olive and citrus groves,” `Ali Moughnieh, head of Tair Debbe municipality, told Human Rights Watch in late October 2006.160 According to MACC SL, 44 civilians have been injured and three killed in the course of working their fields or grazing their animals.161 Habbouba Aoun, coordinator of the Landmines Resource Center in Beirut, said the danger is no longer a lack of awareness of cluster munitions, but the risks posed by agricultural work.162 “At the beginning, people were being injured from doing reconnaissance in their homes,” Allan Poston of the UNDP said in October 2006. “Now, they are getting injured when working for their livelihood.”163

A woman injured by a submunition dud had just come out of an operation when Human Rights Watch visited Najdeh Sha`biyyah Hospital in Nabatiyah on August 30, 2006. A relative of the injured woman, `Aliya Hussein Hayek, 38, told `Aliya’s story:

The accident happened at 8:30 in the morning. `Aliya and her sister Hussneyyeh were picking tobacco. `Aliya was carrying a tobacco bag; when she placed the bag in the car, it exploded. The cluster bomb must have gotten stuck to the bag that she was using to carry the tobacco. She had carried the bag for 300 meters, and it is only when she put it in car that it exploded.

`Aliya had shrapnel in both legs and her face and injuries to the stomach and lost one finger. Hussneyyeh Hussein Hayek, 39, received light injuries.164

The hope of catching the end of the summer tobacco harvest and the urgency of the olive harvest, which takes place in the fall months, forced many civilians to work alongside unexploded submunitions. In the fields of Yohmor, for example, Human Rights Watch observed civilians picking olives as several dozen duds lay scattered around the tree trunks and ladders. Shawki Yousif, the head of Hebbariyeh municipality, said that farmers decided to harvest olives even though the IDF littered the area with submunitions during the war.165 There had been no injuries in the village as of Human Rights Watch’s visit in late October 2006; however, Yousif worried about his neighbors daily risking their lives to harvest their crops.166

In agricultural Tair Debbe, four farmers and one shepherd were injured in the course of their work.167 Hamid Zayed, 47, was injured while grazing his animals, though the wounds on his right leg have healed and he has since returned to work. The four other men—Abdul Karim, 40; Halil Bassoun, 65; Sayan Hussein, 75; Sa`id `Aoun, approximately 40—suffered injuries while working in olive or citrus groves, all in separate incidents.168 `Aoun was still in the hospital when Human Rights Watch visited Tair Debbe two weeks after the incident. The host of separate injuries in Tair Debbe, dispersed over the course of two months, demonstrated the ongoing threat that cluster duds posed to agricultural workers.

Others who resumed work in the fields often were injured in the course of their labor. Dr. `Ali Hajj `Ali, director of the Najdeh Sha`biyyah Hospital in Nabatiyah, told Human Rights Watch that he treated two separate casualties from farm work: a young man was picking grapes from a tree when a submunition fell on his head and exploded, and a young woman was picking tobacco when a submunition blew off two of her fingers.169

The risk of injury from agricultural activities was especially acute since the demining organizations focused initial efforts on more heavily populated areas.170 Frederic Gras of Mines Advisory Group (MAG) said that his organization primarily focused its efforts on where people were living, not where they worked.171 At the time of Human Rights Watch’s October 2006 visit, demining organizations were concerned about increasing dangers in rural areas once the autumn rains start to fall, softening the ground so that submunitions sink and become buried landmines. “We knew the problem would get more complicated because submunitions would get covered by mud,” said an official with the National Demining Office.172 Civilians have a difficult time seeing—and thus avoiding—a submunition covered in mud. As of July 2007, deminers were still dealing with the effects of the rains, which had buried some submunitions and covered others with fresh vegetation.173

Moving through the Town

Civilians have suffered many injuries from submunition duds while merely walking or even sitting in their village. `Ali Haraz was injured in Majdel Selm at about 12 p.m. the day after the ceasefire. He began walking down the main road of his hometown—which “looked like a city of ghosts”—and, while carefully focusing on avoiding a submunition he saw on the road, accidentally stepped on another dud with a ribbon and a green cylinder.174 It immediately exploded. He showed Human Rights Watch shrapnel scars across his chest, legs, and arms; he still had shrapnel in his left middle finger. He spent four days in the Jabal Amel Hospital in Tyre. The US$1,500 the government gave him after his injury was starting to dwindle, and he did not yet know when he would be able to return to his job as a car mechanic. “When you have the war, the war is for one month and three days,” Haraz said. “But the cluster bombs are war for life.”175 Haraz’s injury demonstrated what the head of the municipality of Tair Debbe told Human Rights Watch: “the basic problem is that they cannot move freely in their land.”176

In Deir Qanoun Ras al-`Ein, 14-year-old Elias Muhammad Saklawi was injured on the Monday of the ceasefire (August 14). He said he was sitting on the stairs of his family’s house when something exploded a few meters away, sending shrapnel into his neck. He said, “I had not noticed it [the submunition] before. It was stuck on a lemon tree across the street from the stairs. When the wind blew up, it must have pushed it to the ground and then it exploded.” He said that his family’s house and three or four others on the edge of town were hit by many cluster munitions.177

Submunitions, quite simply, were nearly everywhere. Salih Ramez Karashet, a farmer from al-Quleila, near Tyre, had asked the government to clear the estimated 200 submunitions from his land for weeks. “We started putting stones around the clusters to mark their location—especially because we needed to irrigate the olive grove and we feared that the irrigation would bury them or move them.”178 Karashet was injured when he accidentally stepped on some hay covering a submunition on his way to check on a water pump.

Good-faith clearance efforts also can easily miss an unexploded dud. “You cannot say you have totally cleaned [the submunitions],” Muhammad `Alaa Aldon, the mukhtar of Majdel Selm, said. “The people are scared now. Maybe they have cluster bombs in the olive fields.”179 On the morning of September 27, 2006, a family of boys in Sawane became victims of a submunition in a “cleared” area as they sat underneath a tree outside a collapsed home, seeking protection from the morning sun. Ten-year-old Hussein Sultan said they were watching a bulldozer clear rubble from the war.180 Tragedy struck when a submunution fell from the tree above. Muhammad Hassan Sultan, 16, died; five of his cousins and brothers, `Abbas Sultan, Hussein Sultan, Jamil Sultan, Hilal Sultan, andHassan Sultan, were injured.181

Casualties during Clearance

According to MACC SL, cluster munition duds had injured 25 and killed 17 clearance professionals by January 15, 2008.182 Chris Clark of MACC SL said that Army demining cluster deaths as of the end of October 2006 were all the result of civilians collecting cluster munitions in boxes and bags.183 “The danger then multiplies,” said Ryszard Morczynski, UNIFIL’s civil affairs officer.184 A UNIFIL team working just outside of Tebnine, for example, said that when they arrived to clear the fields, people had already gathered the cluster munitions into piles for the deminers to explode.185 Another major source of deminer casualties is the density of the submunitions. Dalya Farran of MACC SL explained, “If a deminer/searcher is working in an area with 10-20 sub-munitions for example, he/she is less exposed to an accident than a deminer/searcher working in a clearance site with 100-200 sub-munitions.”186

In some areas, civilians have been unable to wait for professional clearance and instead have taken it upon themselves to begin removing submunitions. Farmers pressured by the quickly passing harvest season cleared unexploded duds alone and without guidance. So-called community clearance by individuals untrained in munitions and bomb destruction endangers both the clearer himself and any nearby civilians.

Shadi Sa`id `Aoun, a 26-year-old farmer, talked to Human Rights Watch from his hospital bed in Saida:

I got injured on Wednesday, September 13th [2006] in Tair Debbe. I had gone to work in the orange orchard. After the war, we saw over 1,000 unexploded clusters in my orchard. We exploded over 800 of them. We would put some plastic material with diesel oil and light it up next to the cluster bomb, and the heat would cause it to explode a few minutes later. We had been doing this for 20 to 25 days. In a carton, I had gathered 80 of the cluster bombs. Those looked like they had lost their trigger, so I assumed it was safe to gather them and had not exploded them. The Lebanese Army came on Wednesday and was clearing a neighboring field. I wanted to carry the box with the 80 cluster bombs to the other field. While I was lifting the box, the bottom fell out and one or more of them exploded. My two legs are broken. The left leg went left, and the right leg went right. The bones were crushed.187

In `Ein Ba`al, Hussein `Ali Kiki, a 32-year-old construction worker, told Human Rights Watch about a submunition incident on August 19, 2006, that injured him and killed a friend:

We went to take a number of clusters out of a friend’s orchard. It was the first Saturday after the ceasefire. The orchard is between Batoulay and Ras al-`Ein. I was working with my friend `Ali Muhammad Abu `Eid, who had worked in the past for BACTEC [a demining group]. We were removing the ones with the white ribbons with no difficulty. We had already removed a bunch of them. But then we saw one that looked slightly different. It looks like the other ones but it is a bit thicker. It is also a bit more white with a red dot on it. We did not know how to disarm it, and it exploded. My friend `Ali died immediately. I got injured in my legs. I still can’t walk. The shrapnel tore through muscle and tendons.188

The gathering of scrap metal for income also caused casualties. Fifteen-year-old `Ali Muhammad Jawad had just returned from the hospital when Human Rights Watch visited his home in al-Hallousiyyeh. From his bed, he described how on October 17, 2006, around 4 p.m., he spent the afternoon picking up pieces of shrapnel and metal with his cousin Hamdid `Ali Jawad, 18, to sell for 1,000 or 1,500 Lebanese pounds (the equivalent of 66 cents or $1) per kilo. Hamdid found something unusual on the ground, marked by a painted red stick that he used to poke at the item. `Ali stood two to three meters away from Hamdid when the cluster exploded, killing Hamdid and injuring `Ali.189 The ambulance was slow in coming; `Ali’s family speculates that if it had arrived earlier, they might have been able to save Hamdid. `Ali remained bedridden and did not know when he would be able to return to his job as a blacksmith’s apprentice.

Case Studies

The following three case studies are highlighted because they represent a special circumstance (Tebnine) or egregious examples of the types of civilian harm discussed above (Yohmor and the Zawtars).

Tebnine

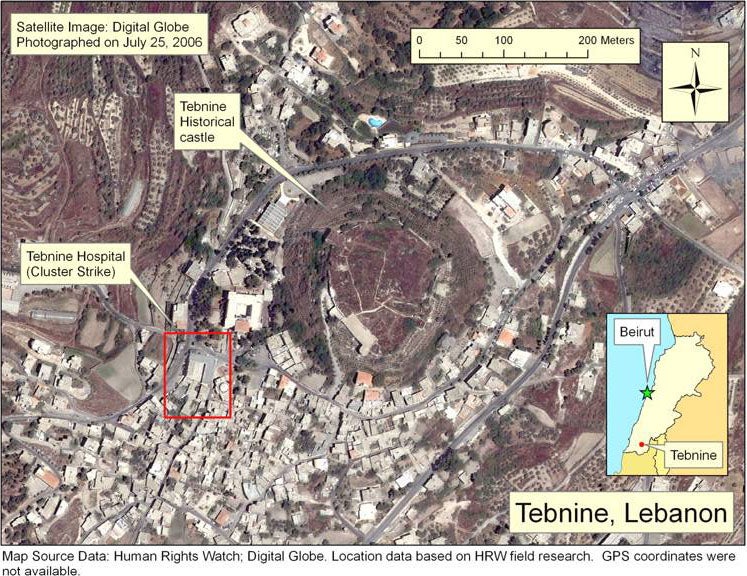

On Sunday, August 13, 2006, Israeli forces struck Tebnine Hospital with cluster munitions. Approximately 375 civilians and military noncombatants, including medical staff, patients, and people who had sought refuge, were in the hospital during the attack. Because “this whole area was infested with cluster bombs,” the civilians were trapped in the hospital until a path was cleared to allow them to escape.190 The hospital is a very large, multistory, multi-wing complex that has been

An Israeli cluster munition caused damage to the Tebnine Hospital in an attack on August 13, 2006. Hundreds of Israeli-manufactured M85 submunitions were removed from the roof, parking lot, and streets in front of the hospital. The damage was still visible on August 18, 2006. © 2006 Marc Garlasco/Human Rights Watch

in operation for many years, including during the Israeli occupation of south Lebanon. Human Rights Watch observed Red Cross flags flying on the hospital.

Tebnine Hospital is affiliated with the Ministry of Health and is administered by the Lebanese Army. Because the hospital was being renovated at the time of the conflict, it was only partially functioning, focusing primarily on emergency cases. During the conflicts in 1993 and 1996, the hospital had provided refuge to civilians and had never been hit. According to Musa, a 33-year-old nurse at the hospital, “From the beginning [of the 2006 war], people started coming to the hospital to seek refuge—initially from Tebnine and then from all over Bint Jbeil.”191 During the first 10 days of the war, 10,000 civilians passed through the hospital, with about 2,000 people inside at any given time. Dr. Ahmed Hussein Dbouk told Human Rights Watch that the hospital had been providing shelter because people felt safe there.192

Yousif Fawwaz, mukhtar of Tebnine, said, “When Israel decided to pull out, they littered the whole area with cluster bombs.”193 At around 5 p.m. on August 13, 2006, some 15 hours before the ceasefire, the IDF commenced a cluster attack around the hospital. The Lebanese Army colonel, the administrator of the hospital, said that he remained in a safe room in the hospital with about 300 others for about two hours during the attack.194 Afterward, duds covered the streets surrounding the hospital, the roof of the hospital, and the receiving areas for ambulances. Those who were in the hospital were trapped until the following day when a path to the hospital was cleared with a bulldozer tractor. Immediately after the path was cleared, NGO deminers and the Lebanese Army removed the cluster munitions next to the path.195

Human Rights Watch researchers visited Tebnine Hospital twice following the attack and saw pockmarked walls, broken windows, destroyed medical equipment, and damaged sidewalks and pavement surrounding the hospital. One submunition had blown up in a hospital room, destroying much of the room and the ceiling in the room below. Human Rights Watch researchers also found an unexploded M85 submunition on the roof of the hospital a week after the attack.

According to the Lebanese Army colonel, “MAG [Mines Advisory Group] removed approximately 50 clusters from within the campus of the hospital.”196 Although they had removed the submunitions on the premises, many still surrounded the hospital more than two months after the attack. When Human Rights Watch researchers again visited the hospital on October 24, 2006, deminers had taped off the grassy area directly next to the hospital because they had not yet cleared it of submunitions.

The problem in Tebnine was especially acute because so many of the submunitions had failed to explode on contact. Dalya Farran of MACC SL said, “There seems to be a huge failure rate [in the country]. In some cases, 50 percent. In Tebnine, we are seeing a failure rate close to 70 percent.”197 This high number of duds will continue to haunt the residents in and surrounding Tebnine until deminers complete clearance.

Although no one was injured during the cluster attack on the hospital, the attack seriously degraded the hospital’s capabilities, placing those seeking medical attention and medical workers, particularly ambulance drivers, at extreme risk. Some civilians who were in desperate need of medical attention had to zigzag through submunitions to make it to the hospital. Furthermore, according to Dr. Dbouk, who was in the hospital during the attack, many people suffered from panic attacks and one person died of a heart attack, possibly induced by the shelling.198

This attack on a hospital is of particular concern as hospitals, including military hospitals, are protected places under international humanitarian law and may not be the object of an attack unless they are being used for military purposes.199 Human Rights Watch’s researchers did not find any information suggesting that Hezbollah

was present at the time of attack or was using the hospital for military purposes.200 One nurse added, “Here in the hospital we did not hear anything [i.e. any fire] coming out of Tebnine.”201

A main road runs close to the hospital—a road that Hezbollah fighters may have been using to transit north-south. However, there is reason to question the legality of using an area-effect weapon on any target that is even in close proximity to a hospital. If Israel was targeting Hezbollah combatants using the road, the IDF must justify why it chose to use cluster munitions to target fighters while they were close to a protected place and not at some other point on the route.

If it can be shown the Israel indiscriminately or deliberately attacked the hospital without military justification and with criminal intent, it would amount to a war crime. It is imperative that Israel conduct a thorough investigation of this incident, make the results public, identify those responsible for ordering and carrying out the attack, and hold them responsible for any violations or war crimes should the evidence substantiate such conclusions. The UN should include investigation of the cluster bombing of Tebnine within the mandate of the International Commission of Inquiry into reports of violation of international humanitarian law in Lebanon and Israel that Human Rights Watch is calling on the Secretary-General of the United Nations to establish.

Yohmor

The IDF heavily bombarded Yohmor, a large village just north of the Litani River, with cluster munitions in the two days prior to the ceasefire. When Human Rights Watch researchers first arrived in the town on August 17, 2006, the Lebanese Army and UN demining groups were destroying cluster duds throughout the town. After two months of clearance work, when Human Rights Watch returned on October 26, 2006, unexploded submunitions still lay scattered in Yohmor’s gardens and fields. Submunitions could be found throughout the village of 7,500 civilians. “People here can’t move,” Kasim M. `Aleik, the head of Yohmor municipality, told Human Rights

Watch in October.202 “You can see [submunitions] everywhere. Deep inside the town. Everywhere, down to the river.”203

During the war, the IDF occupied al-Taibe, a town just across the Litani from Yohmor. Frequent firefights between the IDF and Hezbollah, on the north side of the Litani, ensued. Civilians reported that there were cluster munition attacks at night on the last two days of the war.204 Fortunately, most of the village’s 400 families had left Yohmor by the final strikes on the town, with only 20 families remaining until the end of the war.205

The day after the ceasefire took effect, Mines Advisory Group sent personnel to the village to warn the carloads of villagers flocking back to Yohmor of the dangers of unexploded submunitions.206 A MAG representative later wrote:

When our team first visited the area on 15th August, a day after the ceasefire, we were shocked by the level of contamination. Yohmor was particularly affected and we began clearance straight away. Bomblets littered the ground from one end of the village to the other. They were on the roofs of all the houses, in gardens and spread across roads and paths. Some were even found inside houses—they had fallen through windows or holes in the roof blasted by artillery and aircraft.207

Many families returning to their homes found their houses too dangerous to live in; some, however, decided to return to their homes despite the risks, trying to be as careful as possible. Human Rights Watch interviewed Hajje Fatima Jawad Mroue, 64, shortly after she returned to Yohmor. Submunition strikes had pockmarked her home, leaving a hole in her roof. Unexploded M42 submunitions littered her gardens and the grove of fruit trees. Though she would be unable to pick ripe fruit, she was happy to be home.208

As of October 2006, cluster duds had injured at least five Yohmor civilians and killed one. Shortly after the ceasefire, Salimah Barakat emerged from her home to clear the rocks and rubble blocking her pathway.209 She accidentally exploded a dud while cleaning and spent several days in the hospital for shrapnel wounds. A submunition explosion killed Yousif Ibrahim Khalil, 30, while he attempted to help clear submunitions in the road the day after the war.210 “He was cleaning around it to get it out of the ground and it exploded,” his friend Kasim M. `Aleik remembered.211 Another civilian was harmed in Yohmor when a civilian was doing self-clearance with a bulldozer.212 Hussein `Ali Ahmed was injured in late September, also while cleaning his home, and is now partially paralyzed and unable to talk.213 Two weeks later, on October 10, Hussein `Ali `Aleik exploded a submunition while walking around his home in Yohmor.214

Yohmor, like most of south Lebanon, relies mostly on agriculture for income. Approximately 60 percent of the village works in agriculture, with 150 families farming in tobacco alone. Out of economic necessity, some villagers returned to work in their fields, despite the prevalence of submunitions throughout rural Yohmor. In October 2006, Human Rights Watch researchers witnessed a farmer picking olives from a grove scattered with several dozen red-painted sticks demarcating still-uncleared submunitions.

As of late October 2006, MAG deminers—responsible for the clearance efforts in the area—had removed most unexploded submunitions from the houses, access roads, roofs, and pathways to homes.215 The deminers had progressed to clearing the gardens just outside the homes, but the fields remain the third, and last, priority in the area; MAG field manager Frederic Gras emphasized that his group needed to focus on where people lived.216 Two MAG teams scoured Yohmor with metal detectors, while three teams canvassed the area to locate the submunitions visually. Gras estimated that clearing Yohmor would be, at minimum, a year’s work for the MAG teams. There were “submunitions absolutely everywhere” at the end of the war, and MAG estimates that there was a 30 percent dud rate in the area.217

Lebanese military personnel said that they found remnants of 15 M26 MLRS rockets, some of which were still full of submunitions (each rocket contains 644 M77 submunitions). Human Rights Watch researchers saw more than 100 unexploded M77 and M42 submunitions, the latter from 155mm artillery projectiles, along the town’s roads, in gardens, on roofs, and in homes. UN deminers showed researchers unexploded BLU-63 submunitions from Vietnam War-era CBU-58B cluster bombs. Researchers also saw CBU-58B canisters that were load-stamped 1973.

Zawtar al-Gharbiyeh and Zawtar al-Sharkiyeh

On August 15, 2006, the day after the ceasefire, Muhammad Darwish and his friend `Ali Khalil Turkiye were picking fruit from a tree behind a friend’s home in Zawtar al-Gharbiyeh. When Turkiye grabbed a piece of fruit, a submunition fell from a branch, landing on him. Darwish, who was two to three meters away, recalled, “There was a very big explosion. I can’t tell you what happened, but I saw that `Ali was killed.”218 Darwish was injured and still has shrapnel in his body today. Darwish and Turkiye were the first of many casualties in the Zawtars.

Zawtar al-Gharbiyeh (Western Zawtar) and Zawtar al-Sharkiyeh (Eastern Zawtar), located just north of the Litani River, used to be one village, but have split into two. Israel heavily hit the two Zawtars, particularly with cluster munitions in the last week of the fighting. Although no one is known to have been injured during the attacks, buildings including a primary school were severely damaged. According to MACC SL, from the ceasefire until January 15, 2008, cluster duds had injured 10 civilians and killed one in the Zawtars.219

Roughly 90 to 95 percent of the towns’ residents left during the war.220 Some, however, like 56-year-old Muhammad `Ali Yaghi, stayed during the entire conflict and witnessed the barrage of cluster munitions. He said Israel began dropping cluster munitions in the fields outside the village on August 8 and inside the village during the last four days. “All of the town was destroyed the last four days. I was with my brother when they fell, about August 8 in the fields. They started in the surrounding areas, then here in town.”221 Because Yaghi’s home was littered with cluster munitions, he was forced to seek refuge at his brother’s house down the road for the remainder of the war.

When Human Rights Watch researchers visited Yaghi’s home, they counted 18 submunition holes in the ceilings of his house, including holes above his daughter’s bed. Because of the immediate danger posed to his family by duds, Yaghi collected submunitions from around his home by himself. He told Human Rights Watch, “There were 22 bombs around the house in the paprika garden. I cleared them. I took them to some place, ducked behind a wall, and threw them. The explosion was about 20 meters in diameter.”222 Yaghi’s method of “clearance” was not only extremely dangerous to himself, but also to those in the area where he disposed of the munitions. Tossed duds that may have failed to explode will pose a future threat in the area.

Yaghi’s home was one of many buildings damaged by cluster munitions. Particularly troubling was the severe damage done to al-Sheikh Naïm Mahdi primary school in Zawtar al-Sharkiyeh. Human Rights Watch researchers observed shrapnel damage all

Al-Sheikh Naïm Mahdi primary school in Zawtar al-Sharkiyeh exhibits the typical pockmarked walls of a building struck by cluster munitions. On October 23, 2006, the municipal leader said that deminers had removed 2,000 to 3,000 submunitions from the property. © 2006 Bonnie Docherty/Human Rights Watch

over the face of the building and small pits in the pavement surrounding the school caused by submunitions. Ahmed `Ali Mahdi Suleiman, the municipal leader of Zawtar al-Sharkiyeh, said the Lebanese Army and MAG cleared the school following the ceasefire, removing 2,000 to 3,000 submunitions.223 According to the local people interviewed by Human Rights Watch, Hezbollah had not used the school at any time during the war, and there had been no Hezbollah forces anywhere in the town.

The hazards of cluster munitions continued to plague the residents of the Zawtars, with injuries still taking place months after the conflict ended. One of the first casualties was 23-year-old Amin Mustafa Yaghi, who was injured by a cluster munition only a week after the ceasefire. He and his brother were walking down the road to visit his cousin when his brother saw something in the road that looked like a stone. “My brother kicked it to see what it was,” Yaghi recalls. “Then it exploded. It hurt my hand, arm, neck, and side—the same for my brother. For one week after the explosion I couldn’t hear.”224 When Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed Yaghi two months after the accident, he still had shrapnel in his neck, side, and leg. His brother also had pieces of the submunition embedded in his neck so close to a nerve that they could not be safely removed.

A submunition also injured 18-year-old mechanic Muhammad Abdullah Mahdi on October 4, 2006. Mahdi was moving a car motor behind the garage when a submunition inside the motor exploded. Mahdi’s boss rushed him to the hospital in Nabatiyah. Mahdi told Human Rights Watch, “I spent four days in the hospital. I hemorrhaged and had five units of blood transferred. I still have foreign bodies [inside me]. I will be like this for four months.”225 Mahdi’s right leg is injured, and he lost half of his left hand. A family member lamented that Mahdi has suffered both from loss of work and from psychological trauma because of the accident.226

A few days after Mahdi was injured, a submunition injured 64-year-old `Ali Khalil Loubani while he was picking up rubble from destroyed homes. Unable to drive his taxi during the conflict and unable to work in the tobacco fields since they were littered with clusters, he took a job filling holes in the road for $20 per day. Loubani said, “On October 7, at 8 a.m., I was working. I brought some ruins from damaged houses and went to fill holes in the road on the border between the two Zawtars. The ruins where I was working contained cluster bombs. I didn’t see it before it exploded…. I didn’t know anything about clusters.”227 Loubani lost part of his fingers from the explosion. Although flesh had been transplanted from his arm to his fingers to restore them, when Human Rights Watch interviewed him, Loubani remained skeptical about being able to return to work as a driver.

Casualties were still amassing in Zawtar when Human Rights Watch visited the town two months after the ceasefire. On October 13, 4-year-old `Ali Muhammad Yaghi was playing in front of his house when a submunition in his neighbor’s garden exploded, injuring him. “Someone exploded a submunition here,” `Ali’s father, Muhammad, recalled. “I saw my son injured in the driveway…. We don’t know how it went off.”228

In addition to the civilian casualties, cluster munitions took an economic toll in Eastern and Western Zawtar. Both communities rely heavily on agriculture, particularly olives and tobacco. Ninety percent of the families in Zawtar al-Sharkiyeh depend directly on agriculture, and the remaining 10 percent benefit from it indirectly.229 The abundance of submunitions in the fields made farming extremely dangerous. One resident stated, “You can’t go to any of the olive groves and tobacco fields. There are bombs in the trees and on the ground.”230 Farmers were faced with the decision of risking their lives to harvest their crops or avoiding their fields out of safety and thus being unable to feed their families.

Many residents feared in the fall of 2006 that the worst was yet to come in the fields. One woman stated, “When it rains, the bombs go into the ground. It’s very dangerous…. Deaths will get worse next summer when [farmers] return to the fields to farm again. The bombs will be less visible.”231

Though most of the submunitions inside the town had been cleared when Human Rights Watch visited, the fields on the outskirts were still heavily inundated with duds. Human Rights Watch researchers saw more than a dozen marked and unmarked submunitions, including BLU-63s and M42s, in two fields on the outskirts of the villages. They also saw several parts of submunitions and five CBU-58B casings collected by civilians. The casings were dated 1973 with a one-year warranty, a troubling indicator of one reason why dud rates had been so high during the conflict.

Four-year-old `Ali Muhammad Yaghi was playing in front of his Zawtar al-Gharbiyeh house when a submunition in his neighbor’s garden exploded. As he showed Human Rights Watch on October 23, 2006, he suffered a serious arm injury. © 2006 Bonnie Docherty/Human Rights Watch

The Socioeconomic Effects of Cluster Munition Contamination

The estimated hundreds of thousands and possibly up to one million submunition duds have greatly disrupted south Lebanon’s heavily agrarian economy. According to UNDP, submunitions have contaminated an estimated 20 square kilometers of agricultural land, which makes up more than half of the land contaminated.232 The UN Food and Agricultural Organization reported that submunitions contaminated at least 26 percent of south Lebanon’s agricultural land, a figure MACC SL described as “very conservative.”233 They blocked access to homes, gardens, fields, and orchards. Chris Clark, the program manager for MACC SL, told Human Rights Watch that “it’s not too much of an exaggeration to say everything is affected.”234 An estimated 70 percent of household incomes in south Lebanon come from agriculture. Unfortunately, the submunitions remaining after the cluster strikes on south Lebanon left farmers unable to harvest or plant crops.235 “They need help,” said Habbouba Aoun, coordinator of the Landmines Resource Center. “They cannot access anymore their source of survival.”236

South Lebanon is heavily dependent on the olive and citrus crops harvested annually and the tobacco crops harvested twice a year. However, in the fall of 2006, unexploded duds contaminated many fields beyond use, and many groves were abandoned. Farmers could not irrigate their fields until they were cleared of duds, as the watering of the fields would cause the duds to sink into the ground and make them more difficult to detect. Many communities consequently lost their 2006 harvest of olives, citrus, and tobacco. “The cluster bombs will definitely affect next year’s crops,” Allan Poston of the UNDP said in October 2006. “At this point, the extent of the effect is not known yet. It will depend on how fast demining can take place.”237 Assessing the monetary economic impact is difficult, given the numerous factors that go into this calculation. Farmers, however, will certainly feel the effects of the war for a long time.

As already described, some farmers decided that the hardship of losing the 2006 crop outweighed the danger of working amidst unexploded submunitions. The head of municipality for Yohmor, where 60 percent of the population works in agriculture, was among those who chose to work in his olive grove despite the risk of stumbling across unexploded clusters in his field. “I’m scared, but I want to work it. I lost money,” he said.238 For the farmers who avoided their fields because of cluster munitions, however, the price of safety was the 2006 harvest.

The leftover submunitions were particularly problematic for olive farmers, who usually harvest the annual crop in the fall months. In November 2006, UNDP estimated that duds contaminated around 4.7 square kilometers of olive groves.239 The olive crop typically alternates between a good crop one year and a bad crop the next; the 2006 harvest was expected to be the good crop. “We can’t work. We lost the season,” said `Ali Muhammad Mansour, the mukhtar of `Aitaroun, where 90 percent of the population works in agriculture.240 “We want to be able to work the new season. People are scared to work.” The mukhtar of Majdel Selm told Human Rights Watch that 50 percent of his village relies on agriculture, but given the numerous cluster duds found in the fields, “We cannot work in the agriculture fields because we are afraid.”241 He estimated that it will be a year before the community can return to the olive groves.

Tobacco farmers also faced devastation, unable to either harvest their crop in 2006 or plant for 2007. Tobacco is collected twice a year—once over the summer, and once six months later. In 2006 submunitions prevented farmers from salvaging tobacco left after the war, which disrupted the scheduled harvest. Human Rights Watch spoke with a tobacco farmer who estimated that he would lose around four million Lebanese pounds, or $2,666, because he could not harvest his crop.242 `Atif Wahba of `Ainata lost the summer crop when he fled the south during the war; when he returned, his field was saturated with clusters so he could not plant for the spring 2007 harvest. Instead, he worked as a day laborer, earning $10 or $20 per day, while his fields went untended.243

Unexploded submunitions continued to interfere with agriculture throughout 2007, even as clearance work reached more areas. While clearance has made significant progress, more remains to be done. Deminers have tried to prioritize agricultural areas based on the timing for cultivating crops and information from the municipalities and the ministerial level.244 Dalya Farran of MACC SL explained:

We built up a [clearance] schedule dividing the different harvest seasons throughout the year…. This means we target the CBU strikes in agricultural lands based on harvest season but we don’t finish…everything within the limited time frame. Then we move teams to another area based on another harvest season.245

Because of the scale of the problem, however, deminers could not immediately address all agricultural land. In 2006 Ahmed Kadre, an olive farmer in Kfar Shufa, told Human Rights Watch that none of the demining organizations had reached his village by October, though the bombing left the olive groves just outside the village unusable.246 Salih Ramez Karashet, a farmer from al-Quleila, near Tyre, had been asking the government to clear the estimated 200 submunitions from his land for weeks. “We started putting stones around the clusters to mark their location—especially because we needed to irrigate the olive grove and we feared that the irrigation would bury them or move them.”247 Until 2007, organizations demining in the region had to make the fields a secondary priority, behind homes and roads, in clearance operations.248

141 The actual number of casualties caused by cluster munitions during the war is not known. Civilians returned to find family members’ bodies in their homes, but could not ascertain whether the cause of death was a cluster strike or other weapons fire. In addition, the hospital staff was too overwhelmed, at the time of the war, to query injured patients or families of the dead about the causes of the injury or death.

142 MACC SL Casualty List; LMRC Casualty List.

143 MACC SL Casualty List. The Landmines Resource Center reported that at least 62 of its 239 civilian casualties, including four killed, were under 18 years old although it did not provide ages for all the victims. It also reported 33 deminer casualties (12 killed and 21 injured) as of January 2, 2008. LMRC Casualty List.

144 Human Rights Watch interview with officer (name withheld), Mine Victims Assistance and Mine Risk Education section, National Demining Office, Beirut, October 20, 2006.

145 “Israeli Cluster Munitions Hit Civilians in Lebanon,” Human Rights Watch news release.

146 Human Rights Watch interview with Ahmed Mouzamer, vice head of Sawane municipality, Sawane, October 26, 2006.

147 Human Rights Watch interview with Salimah Barakat, farmer, Yohmor, October 26, 2006.

148 Human Rights Watch interviews with Hassan `Abbas Hattab, mukhtar, Habboush, and Ibrahim Hattab, Habboush, October 25, 2006.

149 Human Rights Watch interview with Chris Clark, program manager, MACC SL, Tyre, September 14, 2006.

150 Human Rights Watch interview with daughter of Raghda Idriss, Bar`achit, October 24, 2006.

151 MACC SL Casualty List. The Landmines Resource Center found at least 26 percent of its casualties were children. LMRC Casualty List.

152 Human Rights Watch interview with `Ali Fakih, mukhtar, Kfar Dounine, October 24, 2006.

153 Human Rights Watch interview with `Ali Hussein Dabbouk, Deir Qanoun Ras al-`Ein, September 22, 2006.

154 Human Rights Watch interview with Fatima Hussein Hamadi, Deir Qanoun Ras al-`Ein, September 22, 2006.

155 Human Rights Watch interview with Marwa `Ali Mar`i, Jabal Amel Hospital, Tyre, August 18, 2006.

156 Human Rights Watch interview with Hassan Hussein Tahini, Jabal Amel Hospital, Tyre, August 18, 2006. From the ceasefire on August 14 until August 18, the hospital had received 12 cluster munition victims. Dr. Ahmed Mroue told Human Rights Watch that the hospital received a total of 841 injured patients during the conflict and 96 on the first day of the ceasefire. Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. Ahmed Mroue, Jabal Amel Hospital, Tyre, August 18, 2006.

157 Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. `Abdel Nasser Farran, Jabal Amel Hospital, Tyre, August 18, 2006.

158 Human Rights Watch interview with `Abbas Yousif `Abbas, Najdeh Sha`biyyah Hospital, Nabatiyah, August 30, 2006.

159 Human Rights Watch interview with witness (name withheld), Halta, October 22, 2006.

160 Human Rights Watch interview with `Ali Moughnieh, head of Tair Debbe municipality, Tair Debbe, October 21, 2006.

161 MACC SL Casualty List. The Landmines Resource Center reported 51 civilians were injured and seven killed doing agricultural activities. LMRC Casualty List.

162 Human Rights Watch interview with Habbouba Aoun, coordinator, Landmines Resource Center, Beirut, October 20, 2006.

163 Human Rights Watch interview with Allan Poston, chief technical advisor, National Demining Office, UNDP, Beirut, November 29, 2006.

164 Human Rights Watch interview with relative of `Aliya Hussein Hayek (name withheld), Najdeh Sha`biyyah Hospital, Nabatiyah, August 30, 2006.

165 Human Rights Watch interview with Shawki Yousif, head of Hebbariyeh munipality, Hebbariyeh, October 22, 2006.

166 Ibid.

167 Human Rights Watch interview with `Ali Moughnieh, head of Tair Debbe municipality, Tair Debbe, October 21, 2006.

168 Ibid.

169 Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. `Ali Hajj `Ali , director of the Najdeh Sha`biyyah Hospital, Nabatiyah, August 30, 2006.

170 Human Rights Watch interview with officer (name withheld), Mine Victims Assistance and Mine Risk Education section, National Demining Office, Beirut, October 20, 2006.

171 Human Rights Watch interview with Frederic Gras, technical field manager, Mines Advisory Group, Yohmor, October 26, 2006.

172 Human Rights Watch interview with officer (name withheld), Mine Victims Assistance and Mine Risk Education section, National Demining Office, Beirut, October 20, 2006.

173 Email communication from Julia Goehsing, program officer, MACC SL, to Human Rights Watch, May 14, 2007; email communication from Julia Goehsing, program officer, MACC SL, to Human Rights Watch, July 20, 2007.

174 Human Rights Watch interview with `Ali Haraz, car mechanic, Majdel Selm, October 26, 2006.

175 Ibid.

176 Human Rights Watch interview with `Ali Moughnieh, head of Tair Debbe municipality, Tair Debbe, October 21, 2006.

177 Human Rights Watch interview with Elias Muhammad Saklawi, Deir Qanoun Ras al-`Ein, September 22, 2006.

178 Human Rights Watch interview with Salih Ramez Karashet, farmer, Hammoud Hospital, Saida, September 22, 2006.

179 Human Rights Watch interview with Muhammad `Alaa Aldon, mukhtar, Majdel Selm, October 26, 2006.

180 Human Rights Watch interview with Hussein Sultan, Sawane, October 26, 2006.

181 Human Rights Watch interview with Ahmed Mouzamer, vice head of Sawane municipality, Sawane, October 26, 2006.

182 MACC SL Casualty List. As of January 2, 2008, the Landmines Resource Center had recorded 33 deminer casualties including 12 killed. LMRC Casualty List.

183 Human Rights Watch interview with Chris Clark, program manager, MACC SL, Tyre, October 21, 2006.

184 Human Rights Watch interview with Ryszard Morczynski, civil affairs officer, UNIFIL, al-Naqoura, October 27, 2006.

185 Human Rights Watch interview with UNIFIL deminer (name withheld), Tebnine, October 24, 2006.

186 Email communication from Dalya Farran, media and post clearance officer, MACC SL, to Human Rights Watch, January 16, 2008.

187 Human Rights Watch interview with Shadi Sa`id `Aoun, farmer, Hammoud Hospital, Saida, September 22, 2006.

188 Human Rights Watch interview with Hussein `Ali Kiki, construction worker, `Ein Ba`al, September 22, 2006. When asked whether Hezbollah had been firing rockets from the fields, he said, “The field I was in at the time I got injured did not have launching pads. However, fields next to it did. At the beginning, the Israelis were firing most of the clusters on places where there were rocket launchers. But after that, they started throwing them everywhere.” Ibid.

189 Human Rights Watch interview with `Ali Muhammad Jawad, al-Hallousiyyeh, October 21, 2006.

190 Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. Ahmed Hussein Dbouk, Tebnine Hospital, Tebnine, October 24, 2006.

191 Human Rights Watch interview with Musa (last name withheld), nurse, Tebnine Hospital, Tebnine, August 20, 2006.

192 Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. Ahmed Hussein Dbouk, Tebnine Hospital, Tebnine, October 24, 2006.

193 Human Rights Watch interview with Yousif Fawwaz, mukhtar, Tebnine, October 24, 2006.

194 Human Rights Watch interview with colonel (name withheld), Lebanese Army, Tebnine, August 20, 2006.

195 Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. Ahmed Hussein Dbouk, Tebnine Hospital, Tebnine, October 24, 2006.

196 Human Rights Watch interview with colonel (name withheld), Lebanese Army, Tebnine, August 20, 2006.

197 Human Rights Watch interview with Dalya Farran, media and post clearance officer, MACC SL, Tyre, October 21, 2006.

198 Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. Ahmed Hussein Dbouk, Tebnine Hospital, Tebnine, October 24, 2006.

199 See Fourth Geneva Convention, art. 18; Protocol I, art. 12. This protection ceases if a medical establishment is used to commit “acts harmful to the enemy.” Fourth Geneva Convention, art. 19; Protocol I, art. 13.

200 Human Rights Watch interview with Musa (last name withheld), nurse, Tebnine Hospital, Tebnine, August 20, 2006; Human Rights Watch interview with Yousif Fawwaz, mukhtar, Tebnine, October 24, 2006.

201 Human Rights Watch interview with Musa (last name withheld), nurse, Tebnine Hospital, Tebnine, August 20, 2006.

202 Human Rights Watch interview with Kasim M. `Aleik, head of Yohmor municipality, Yohmor, October 26, 2006.

203 Ibid.

204 Human Rights Watch interview with Salimah Barakat, farmer, Yohmor, October 26, 2006.

205 Human Rights Watch interview with Kasim M. `Aleik, head of Yohmor municipality, Yohmor, October 26, 2006.

206 Human Rights Watch interview with Frederic Gras, technical field manager, Mines Advisory Group, October 26, 2006.

207 Sean Sutton, Mines Advisory Group, “Lebanon Special Report: Yohmor Village—Imprisoned by Bombs,” http://www.reliefweb.int/rw/rwb.nsf/db900SID/YAOI-6TT9QW?OpenDocument (accessed September 20, 2006).

208 Human Rights Watch interview with Hajje Fatima Jawad Mroue, Yohmor, August 17, 2006.

209 Human Rights Watch interview with Salimah Barakat, farmer, Yohmor, October 26, 2006.

210 Human Rights Watch interview with Kasim M. `Aleik, head of Yohmor municipality, Yohmor, October 26, 2006.

211 Ibid.

212 Human Rights Watch interview with Frederic Gras, technical field manager, Mines Advisory Group, October 26, 2006.

213 Human Rights Watch interview with Kasim M. `Aleik, head of Yohmor municipality, Yohmor, October 26, 2006.

214 Ibid.

215 Human Rights Watch interview with Frederic Gras, technical field manager, Mines Advisory Group, Yohmor, October 26, 2006.

216 Ibid.

217 Ibid.

218 Human Rights Watch interview with Muhammad Darwish, Zawtar al-Gharbiyeh, October 23, 2006.

219 MACC SL Casualty List. The Landmines Resource Center, as of January 2, 2008, reported 20 injuries and one death from the Zawtars.

220 Human Rights Watch interview with `Ali `Aqil Shaytani, Zawtar al-Sharkiyeh, October 23, 2006; Human Rights Watch interview with Ahmed `Ali Mahdi Suleiman, mukhtar, Zawtar al-Sharkiyeh, October 23, 2006.

221 Human Rights Watch interview with Muhammad `Ali Yaghi, Zawtar al-Gharbiyeh, October 23, 2006.

222 Ibid.

223 Human Rights Watch interview with Ahmed `Ali Mahdi Suleiman, mukhtar, Zawtar al-Sharkiyeh, October 23, 2006.

224 Human Rights Watch interview with Amin Mustafa Yaghi, Zawtar al-Gharbiyeh, October 23, 2006.

225 Human Rights Watch interview with Muhammad Abdullah Mahdi, car mechanic, Zawtar al-Sharkiyeh, October 23, 2006.

226 Human Rights Watch interview with family member of Muhammad Abdullah Mahdi (name withheld), Zawtar al-Sharkiyeh, October 23, 2006.

227 Human Rights Watch interview with `Ali Khalil Loubani, Zawtar al-Sharkiyeh, October 23, 2006.

228 Human Rights Watch interview with Muhammad Yaghi, Zawtar al-Gharbiyeh, October 23, 2006.

229 “Lebanon: Cluster Bombs Threaten Farmers' Lives, Hamper Olive Harvest,” Reuters, November 15, 2006, http://www.alertnet.org/thenews/newsdesk/IRIN/50b5549dfd66b212ca120a7a9e353f31.htm (accessed September 3, 2007).

230 Human Rights Watch interview with `Ali Aqil Shaytani, Zawtar al-Sharkiyeh, October 23, 2006.

231 Human Rights Watch interview with Salwa Yaghi, Zawtar al-Gharbiyeh, October 23, 2006.

232 UNDP, “CBU Contamination by Land Use,” current as of November 29, 2006.

233 Email communication from Julia Goehsing, program officer, MACC SL, to Human Rights Watch, July 20, 2007.

234 Human Rights Watch interview with Chris Clark, program manager, MACC SL, Tyre, October 23, 2006.

235 UNOCHA, “Lebanon: Cluster Bomb Fact Sheet,” September 19, 2006.

236 Human Rights Watch interview with Habbouba Aoun, coordinator, Landmines Resource Center, Beirut, October 19, 2006.

237 Human Rights Watch interview with Allan Poston, chief technical advisor, National Demining Office, UNDP, Beirut, November 29, 2006.

238 Human Rights Watch interview with Kasim M. `Aleik, head of Yohmor muncipality, Yohmor, October 26, 2006.

239 UNDP, “CBU Contamination by Land Use,” current as of November 29, 2006.

240 Human Rights Watch interview with `Ali Muhammad Mansour, mukhtar, `Aitaroun, October 27, 2006.

241 Human Rights Watch interview with Muhammad `Alaa Aldon, mukhtar, Majdel Selm, October 26, 2006.

242 Human Rights Watch interview with `Atif Wahba, farmer, `Ainata, October 27, 2006.

243 Ibid.

244 Human Rights Watch interview with Allan Poston, chief technical advisor, National Demining Office, UNDP, Beirut, November 29, 2006; email communication from Dalya Farran, media and post clearance officer, MACC SL, to Human Rights Watch, January 16, 2008.

245 Email communication from Dalya Farran, media and post clearance officer, MACC SL, to Human Rights Watch, January 16, 2008.

246 Human Rights Watch interview with Ahmed Kadre, farmer, Kfar Shufa, October 23, 2006.

247 Human Rights Watch interview with Salih Ramez Karashet, farmer, Hammoud Hospital, Saida, September 22, 2006.

248 Human Rights Watch interview with Frederic Gras, technical field manager, Mines Advisory Group, Yohmor, October 26, 2006. Human Rights Watch interview with officer (name withheld), Mine Victims Assistance and Mine Risk Education section, National Demining Office, Beirut, October 19, 2006.