VI. US Deportation Policy Violates Human Rights

Since the beginning of the nation state, control over immigration has been understood as an essential power of government. In recent history, governments have allowed limits on their immigration power, recognizing that it may only be exercised in ways that do not violate fundamental human rights.98 Therefore, while international law does support every state’s right to set deportation criteria and procedures, it does not allow unfettered discretion to deport all non-citizens in all circumstances.

When Congress changed deportation law in 1996 it broke with international human rights standards in ways never before attempted in the United States. Four important human rights are violated by US deportation policies as applied to immigrants with criminal convictions: the right to raise defenses to deportation, the principle of proportionality, the right to family unity, and the right to protection from return to persecution. In this chapter, we describe these human rights standards and highlight examples of people who were ordered deported in contravention of these norms.

The Right to Raise Defenses to Deportation

A primary purpose of human rights law is to define rights protecting the individual against the coercive powers of the state. Deportation, which removes an immigrant from the community with which he or she has built close and enduring ties, is an example of a coercive state power. However, the recognized legitimate interests of states in deporting certain non-citizens, combined with the relative ease by which deportation can be accomplished, have caused government officials and the public at large to lose sight of just how serious and coercive the state’s decision to deport really can be.

Deported individuals lose their ability to live with close family members in a country that they may reasonably view as “home.” They are deprived of raising their children or living in the same country as their parents, they lose friends and communities, and their ability to work may be restricted as well. In their countries of nationality, people deported from the United States for criminal convictions are often stigmatized and have difficulty finding jobs and establishing or reestablishing family and community connections. Most are barred, either permanently or for decades, from ever re-entering the United States, even for a short visit.

A governmental decision to deprive a person of connection to the place he or she considers home raises serious human rights concerns, requiring at a minimum that the decision to deport be carefully considered, with all relevant impacts and potential rights violations weighed by an independent decision maker. Unfortunately, the US fails to do this on a daily basis.

Instead, the United States takes a “one size fits all” approach to deportation. When non-citizens are facing deportation for criminal convictions, immigration judges can do little more than run conveyer belt deportation hearings in which they rubber stamp the removal orders issued by Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Many non-citizens are legally blocked from raising the closeness of their family relationships or other ties to the United States as well as the likelihood that they may be returned to persecution. Without an ability to raise these equities, deportation hearings provided for immigrants with criminal convictions are devoid of justice, and they violate international standards.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which the United States ratified in 1992,99 states in Article 13 (to which the United States has entered no reservations, understandings or declarations),

An Alien lawfully in the territory of a State Party to the present covenant may be expelled therefrom only in pursuance of a decision reached in accordance with law and shall, except where compelling reasons of national security otherwise require, be allowed to submit the reasons against his expulsion and to have his case reviewed by, and be represented for the purpose before, the competent authority or a person or persons especially designated by the competent authority.100

The UN Human Rights Committee, which monitors state compliance with the ICCPR, has interpreted the phrase “lawfully in the territory” to include non-citizens who wish to challenge the validity of the deportation order against them. In addition, the Human Rights Committee has made this clarifying statement: “if the legality of an alien's entry or stay is in dispute, any decision on this point leading to his expulsion or deportation ought to be taken in accordance with article 13 …. An alien must be given full facilities for pursuing his remedy against expulsion so that this right will in all the circumstances of his case be an effective one.”101

Similarly, Article 8(1) of the American Convention on Human Rights, which the United States signed in 1977,102 states,

Every person has the right to a hearing, with due guarantees and within a reasonable time, by a competent, independent, and impartial tribunal, previously established by law … for the determination of his rights and obligations of a civil, labor, fiscal, or any other nature.103

Applying this standard, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has stated that deportation proceedings require “as broad as possible” an interpretation of due process requirements and include the right to a meaningful defense and to be represented by an attorney.104

While the ability to raise defenses to deportation is provided for in these human rights treaties, not every possible argument against deportation is important enough to call into question the legitimacy of a hearing that denies such arguments’ consideration. For example, a non-citizen who for reasons of personal predilection prefers the economic opportunities and climate in one country to another could not legitimately challenge his hearing under human rights law if he was prevented from making this argument as a defense to deportation.

However, some defenses implicate very important and fundamental rights that non-citizens should be able to raise in their deportation hearings in the United States, including the rights to family unity, ties to a country, proportionality, and the likelihood of return to persecution upon return. Without a hearing that allows for the weighing of these concerns, the right to raise defenses to deportation is undermined.

Several categories of immigrants facing deportation for crimes in the United States are barred from having hearings in which their human rights can be weighed.105 First, there is no mechanism by which immigration courts weigh whether deportation itself is a proportionate penalty imposed for the crimes a non-citizen has committed. Second, immigrants convicted of offenses categorized as aggravated felonies are barred from raising their family relationships or longstanding ties to the United States in a deportation hearing. Third, other non-citizens convicted of crimes cannot raise these issues if they do not fit the very narrow categories contained in the two remaining waivers of deportation (Sections 212(h) and 240A(a)). Fourth, many refugees convicted of aggravated felonies are barred from having their risk of persecution weighed by the courts.

The US policy of blocking certain categories of immigrants convicted of crimes from raising defenses to deportation during their deportation hearings violates international human rights standards. Europe has consistently allowed immigrants to raise these issues during deportation. If deportation infringes on a right protected in the European Convention of Human Rights, such as the right to family life under Article 8, a non-citizen is entitled to “an effective remedy before a national authority” under Article 13.106 This remedy must provide some basic procedural protections as well as be conducted by an authority with sufficient power to rule on the question of whether the infringement of the right is so severe as to render the deportation unlawful.107 In addition, in Stewart v. Canada108 and Canepa v. Canada,109 the Human Rights Committee has determined that hearings weighing family ties should take place prior to deportation.

Given the strength of these standards, many other constitutional democracies require deportation hearings to weigh such defenses to deportation in their domestic practices. In fact, in contrast to the United States, the laws and practices of 61 governments around the world researched by Human Rights Watch offer non-citizens an opportunity to raise family unity concerns, proportionality, ties to a particular country, and/or other human rights standards prior to deportation.

Figure 7: Human Rights Protections in the Deportation Laws of 61 Countries and Territories

|

|

Must weigh family ties as Party to ECHR |

As a matter of domestic law (DL): must weigh family ties prior to deportation |

DL: Must weigh proportionality prior to deportation |

DL: Must weigh ties to a country prior to deportation |

DL: Must give due process prior to deportation |

DL: Must consider human rights prior to deportation |

|

Albania |

X |

X | ||||

|

Andorra |

X | |||||

|

Argentina |

X |

X |

X | |||

|

Armenia |

X |

X | ||||

|

Australia |

X |

X | ||||

|

Austria |

X |

X | ||||

|

Azerbaijan |

X | |||||

|

Belgium |

X |

X | ||||

|

Bosnia & Herzegovina |

X |

X | ||||

|

Brazil |

X | |||||

|

Bulgaria |

X | |||||

|

Canada |

X | |||||

|

Croatia |

X | |||||

|

Cyprus |

X | |||||

|

Czech Republic |

X | |||||

|

Denmark |

X |

X |

X | |||

|

Estonia |

X | |||||

|

Finland |

X |

X | ||||

|

France |

X |

X |

X |

X | ||

|

Georgia |

X | |||||

|

Germany |

X |

X |

X | |||

|

Greece |

X |

X | ||||

|

Guatemala |

X | |||||

|

Hong Kong |

X | |||||

|

Hungary |

X |

X |

X |

X | ||

|

Iceland |

X |

X |

X | |||

|

Ireland |

X |

X |

X | |||

|

Israel |

X | |||||

|

Italy |

X |

X |

X | |||

|

Japan |

X | |||||

|

Latvia |

X | |||||

|

Liechtenstein |

X | |||||

|

Lithuania |

X |

X |

X | |||

|

Luxembourg |

X | |||||

|

Macedonia |

X |

X |

X | |||

|

Malta |

X | |||||

|

Moldova |

X | |||||

|

Monaco |

X | |||||

|

Netherlands |

X |

X | ||||

|

New Zealand |

X | |||||

|

Norway |

X |

X |

X |

X | ||

|

Poland |

X | |||||

|

Portugal |

X |

X | ||||

|

Romania |

X | |||||

|

Russia |

X | |||||

|

San Marino |

X | |||||

|

Serbia |

X | |||||

|

Singapore |

X | |||||

|

Slovakia |

X |

X | ||||

|

Slovenia |

X |

X |

X | |||

|

South Africa |

X |

X | ||||

|

South Korea |

X | |||||

|

Spain |

X |

X | ||||

|

Sweden |

X |

X |

X | |||

|

Switzerland |

X |

X |

X |

X | ||

|

Tajikistan |

X | |||||

|

Turkey |

X | |||||

|

United Kingdom |

X |

X |

X | |||

|

Ukraine |

X | |||||

|

Venezuela |

X |

X |

Source: This chart is based on international comparative law research and analysis performed for Human Rights Watch by the international law firm of Sidley Austin, LLP, February 2007 (legal memo on file with Human Rights Watch).

Case Study: Deportation and Post-Traumatic Stress: Kannareth C.110

Kannareth C., a young man facing deportation to Cambodia, came to the United States with his mother from a refugee camp in Thailand when he was 10 years old. The family entered the United States legally as refugees and became lawful permanent residents. At the age of 15, Kannareth was placed on probation for driving without a license. While he was on probation he was charged with pick pocketing. He also violated his probation by failing to report.

Kannareth has a fiancée and a daughter who was three years old when he went to renew his green card for employment purposes and his criminal record was checked. He was placed in immigration detention and in deportation proceedings. Kannareth wrote,

“I came to the United States of America legally for the opportunities offered of a good life. I was making the best of those opportunities by attending college to learn a trade for the chance at a good employment career. I held a job at the same time to provide for my family. My fiancée and I plan to marry and raise our daughter together. I value my family and have come to realize how much my family need me to be there for them. The thought of having my daughter ask how come I’m not home, saddens me. I regret putting my family through the strain of not having me home, and I regret this matter is before the court. Please understand that I am not a bad person, nor am I a violent person. I just got caught up and lost sight of direction. I have since gotten back on course …. I can once again provide for my family. I ask that you not destroy my dreams and plans to be a devoted father and husband, and my ambition to provide a good life to my family.”

Punthea C., Kannareth’s mother, spoke (with the help of an interpreter) with a Human Rights Watch researcher. She was under the care of a psychologist because the problems with her son were triggering old memories associated with her flight from Cambodia. She said,

“I feel very lost without my son. It happened again like during the communist years and the civil war. Basically, that is all coming back. Now, we are being separated again. It makes my chest feel very tight. I can’t talk. And breathing is … in other words it’s like something that lumps in your throat and you can’t talk … I feel very bad inside for my child. He went all through his life not having a father, not having a father figure. With my situation in the camp … I couldn’t give him a normal upbringing, that’s one of the reasons why things happened the way they did. After escaping what I went through and escaping from death, now to come to this point. It’s a lot to lose.”

A clinical social worker who is a therapist at the Program for Torture Victims in California gave a professional evaluation of Punthea, reporting that she is suffering from severe post-traumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder, and that it is her “professional opinion that the deportation of [Punthea’s] son to Cambodia would be severely damaging to [Punthea’s] psychological well-being. She is extremely fearful for her son’s well-being and safety if he is sent to Cambodia, and the thought of him in Cambodia triggers painful and frightening memories of her own torture and the other traumas she experienced in Cambodia.”

Proportionality

Since deportation is such an inherently severe sanction, governmental decisions to impose it are subject to human rights constraints. A person’s status as a non-citizen, his or her conviction of a crime, or the combination of the two, does not extinguish his or her claim to just treatment at the hands of the government, nor does it free a government to ignore fundamental rights in its actions. Even in an area in which governmental powers are known to be robust, such as in immigration, governments must uphold basic notions of fairness and proportionality. The gravely serious burdens that are imposed as a result of deportation require government to act within bounds of reasonableness.

The idea that infringements upon rights must be proportional is explicitly included in the domestic law of many countries around the world,111including the United States.112 International law uses proportionality to ensure that rights are not denied arbitrarily. Bodies enforcing those laws, such as the European Union, the Human Rights Committee and the International Court of Justice have all applied proportionality when analyzing states’ decisions to infringe on important rights, including in the context of deportation.113

However, US courts do not consider deportation a form of punishment,114 and therefore they do not weigh the seriousness of the consequence of deportation against the seriousness of a particular non-citizen’s criminal offense. Striking the right balance in the United States is therefore left to the legislative branch. Whether the proportionality analysis is done in a court, or whether it is done by the legislature, and irrespective of whether deportation is considered a punishment under US law, it is a very severe penalty that seems to outweigh some of the crimes that currently trigger it. This is especially so when mitigating and aggravating factors are not weighed in an individualized hearing.

For example, despite the plain meanings of the words “aggravated” and “felony,” this category includes misdemeanor crimes, even though misdemeanors are generally less serious and involve less violence than felonies. Figure 8 outlines some of the offenses that trigger deportation from the United States. For some of these offenses, deportation seems a very harsh additional penalty to add to a criminal sentence that is comparatively inconsequential, reflecting the minor nature of the crimes involved.

Figure 8 – Criminal Sentences Contrasted with Penalty of Deportation

|

Criminal Offense |

Immigration Consequence |

Examples of Likely Federal or State (NY law used) Sentence |

|

2 Shoplifting offenses |

Mandatory detention and deportation115 |

For first conviction individual could receive sentence to several days of community service.116 For second conviction, individual could receive a sentence of up to six months. |

|

Tax evasion, causing loss of more than $10,000 |

Mandatory detention and deportation117 |

Fine equaling tax loss plus zero to six months’ imprisonment118 |

|

Possessing stolen property within five years of entry to the US |

Mandatory detention and deportation119 |

Restitution of property, plus one year’s imprisonment120 |

|

Possession with intent to sell of 35 grams of marijuana |

Mandatory detention and deportation121 |

Between 15 days and up to one year of imprisonment122 |

The case of Suwan provides an example of a relatively minor offense for which deportation seems a disproportionate penalty. He was deported to Cambodia at the age of 34, after living in the United States as a refugee with his wife and two young children. Suwan was a supervisor on a construction crew in Houston, Texas. The crime for which he was deported involved two counts of indecent exposure. Suwan committed these offenses because, according to him, there was no toilet at the construction site that he was supervising, and he was forced to urinate outdoors. After his deportation to Cambodia, Suwan told a CNN reporter, “I think that the crime that I commit … [was not] bad enough to deport me here …. [I had] made it in the States [with my] wife, two kids, a home. Drive to work and back home … I could live the rest of my life [in the United States].”123

In another example, Jose A., originally from El Salvador, entered the United States in 1980 and became a lawful permanent resident in 1990. Jose has three US citizen children and is facing deportation for breaking into a car, a misdemeanor conviction; and for shoplifting a $10 bottle of eye drops from a drug store.124 Jose A. paid a fine for his first offense, and was sentenced to two months’ imprisonment for the shoplifting offense, which he served. His two crimes are considered “crimes of moral turpitude,” making him subject to deportation.

Jose has paid federal income taxes in the United States, and has worked as a technician for a sink and water fountain company. Jose’s wife is a US citizen, with whom he has a young daughter.125 Jose spoke about his wife and reflected on his past crimes and his pending separation from his wife and children:

[My wife] works, has started a credit line. She has a good job, a little house. It’s her time to chase her dreams. I acted foolishly and should pay for those decisions. But I do think the penalty is too harsh. I have been here for 26 years and I would thank the US and say I’m sorry for what I did. I would even accept the deportation if I killed someone or robbed a bank. But now what they are doing to me is robbing my children of their future and their ability to make their own choices … It is a severe punishment to put you in exile away from your whole world. That is the same as taking away your identity.126

Another example is the case of Hamok Yun,127 originally from Korea, who lived in the United States as a lawful permanent resident since the age of two. Yun is married to a US citizen, served in the US Coast Guard, attended Michigan public schools, and worked for seven years at Idra Prince (an industrial machine builder), but lost his job due to his problems with his immigration status.

Yun is facing deportation because he pled guilty to two counts of attempted third degree criminal conduct. After his discharge from the Coast Guard, at the age of 22, Yun began a relationship with a 15-year-old girl. It was this relationship that caused the girl’s parents to bring charges against Yun for statutory rape, resulting in his third degree criminal conduct conviction. A newspaper account of his case explained that “the parents of the girl say they have no ill will toward Yun. In fact, her mother wrote a letter to the immigration judge saying she did not think Yun should be deported. ‘I am stepping forward to say that I feel he has been punished appropriately and to a higher extent than I thought he would be. I feel it is not needed that he be returned to his former country…. I feel that no further punishment is needed.’”128

The principle of proportionality in international law may counsel against imposing the penalty of deportation for these types of offenses, which are less serious than intentional violent crimes such as homicide or (non-statutory) rape.

Case Study: Deportation after Questionable Legal Advice129

Every non-citizen deported for a crime had a separate criminal case prior to his or her deportation hearing. Defense attorneys across the country work hard to stay informed about immigration law, but nevertheless there are some who may give their clients bad advice, which then triggers deportation. It is nearly impossible for these immigrants to convince courts to reopen their criminal cases and resentence them, and thereby nullify the order of deportation.

In one such criminal case, Oscar Hernandez, originally from Mexico, arrived in the United States in 1979 at the age of four and became a lawful permanent resident at the age of 12. As a child, Oscar attended elementary, junior high, and high school in Phoenix. In 1993 Oscar was arrested and placed on probation. He became a father in 1994 and now has two US citizen daughters who live with their mother. Also in 1994, like many other lawful permanent residents, Oscar was recruited by the US Army, though he did not end up joining.

In 1995, while on probation, Oscar was arrested for carjacking. Although Oscar claimed then and now that he was innocent of the carjacking, his attorney advised Oscar to sign a plea agreement in 1998, claiming that he would be sentenced to time served (he had been in jail for three years) and there would be no immigration consequences. Instead, Oscar was sentenced to one year and two months, which he appealed, but which would have made him deportable if his appeal failed. In a shocking turn of events, while Oscar was waiting for his appeal, he was deported by US immigration authorities under his codefendant’s name. Oscar explained his attempts to correct the mistaken identity problem before he was deported:

“I requested to see a supervisor … I told her she was mistaken but she did not listen to me. I was deported as my codefendant, Oscar Barerra Sanchez. I continuously attempted to inform the guards that they had the wrong man and I was repeatedly ignored …. In June 1999 I was deported to Mexico and the following day I returned to the United States with my school identification my brother delivered to me. One-and-a-half years later, in November 2000, I was pulled over for driving without a license.”

Eventually, Oscar was prosecuted for illegal re-entry and sentenced to 57 months in prison. He was once again awaiting deportation when Human Rights Watch interviewed him in 2006. He wrote to the court,

“I … should not have been deported in 1999 as my codefendant. I want to stay in the United States and live here legally. I have been apart from my family for close to 10 years and would like to live with my mother in Phoenix and assist her as she grows older.”

When asked what would happen to Oscar, to his daughters, and to herself if he was deported back to Mexico, Oscar’s mother (who is confined to a wheelchair since she had an accident at her factory job) said,

“He doesn’t know anywhere outside of the US …. All of his brothers are here. Where is he going to go and with who? Right now, he’s the only one that accompanies me. He takes care of me because I can’t do anything. He cooks for me, he cleans the house, he picks up my medicine, and he takes me to the doctor. And if my son weren’t here, what would become of me? ... Like I told the judge once, if I would have seen that my son was bad, I myself would have turned him in to the police because I don’t want any of my children to be delinquents. I hope in God that he listens to me, that they take him out of jail and not out of the country.”

Family Unity

The international human right to family unity finds articulation in numerous human rights treaties. The concept is also incorporated into the domestic law of the United States. For example, in the context of custody rights for grandparents, the US Supreme Court has held that the “right to live together as a family” is an important right deserving constitutional protection, and an “enduring American tradition.”130

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that “[t]he family is the natural and fundamental group unit of society and is entitled to protection by society and the State.”131 The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights states in Article 17(1) that no one shall be “subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence.” Article 23 states that “[t]he family is the natural and fundamental group unit of society and is entitled to protection by society and the state,” and that all men and women have the right “to marry and to found a family.” The right to found a family includes the right “to live together.”132

As the international body entrusted with the power to interpret the ICCPR and decide cases brought under its Protocol, the Human Rights Committee has explicitly stated that family unity imposes limits on states’ power to deport.133 In Winata v. Australia,134 the committee found a violation where Australia sought to deport two Indonesian nationals whose 13-year-old son, Barry, had been born in, and had become a citizen of, Australia. The committee was unimpressed by Australia’s arguments that the petitioners were asserting a “claim[] to residence by unlawfully present aliens,” noting that instead the petitioners merely asserted that “forcing them to leave would be arbitrarily interfering with their family life.”135

The committee also rejected Australia’s argument that the family had the power to decide whether or not to separate, since they could choose to return to Indonesia as a group. The committee looked at the strong family ties to Australia and also the impact on Barry136 to decide that deportation would constitute not only arbitrary interference with the family under Article 17 in conjunction with Article 23, but also a failure to provide necessary measures for the protection of a minor under Article 24.137

Even in a case in which the governmental interest in deportation was strong because a non-citizen was found deportable due to prior criminal convictions, the committee found a violation of the same rights in Madafferi v. Australia, involving an Italian national who had married an Australian national and had four Australian children, and who had been ruled deportable based on prior crimes in his native Italy.138

The Council of the European Union, without challenging in general states’ power to deport non-citizens, imposes limitations in order to protect family relationships. When making deportation decisions, the council has found that the state must consider “the severity or type of offence against public policy or public security committed by the family member, or the dangers that are emanating from that person.”139 According to the council, states must also “take due account of the nature and solidity of the person’s family relationships and the duration of his residence in the Member State and of the existence of family, cultural and social ties with his/her country of origin.”140

Case law from the European Court on Human Rights (see case study: Boultif Test, above) has provided additional guidance to member countries on respecting family unity during deportation on criminal grounds, finding that they should weigh several factors including: the nature and seriousness of the offense; the length of stay in the host country; rehabilitation; spousal relationships; the existence of children; and the potential difficulties family members would face in relocating to the country of origin.141

The American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man142 features several provisions relevant to the question of deportation of non-citizens with criminal convictions and strong family ties. Article V protects every person against “abusive attacks upon … his private and family life.”143 Under Article VI, “[e]very person has the right to establish a family, the basic element of society, and to receive protection therefor.”144 The American Convention on Human Rights, to which the United States is a signatory,145 contains analogous provisions.146 The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights case, Wayne Smith and Hugo Armendáriz v. United States of America, relies on several of these provisions to challenge the US policy of deporting non-citizens with criminal convictions without regard to family unity. 147 The Smith and Armendáriz case was ruled admissible by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights,148 and Human Rights Watch has submitted an amicus curiae brief to the Commission in support of Petitioners Smith and Armendáriz. As of this writing, hearings in the case are expected in July 2007.

In light of these strong international standards, the United States has fallen far behind the practice of governments around the world in terms of providing protection for family unity in deportation proceedings. As shown above (Figure 7), 52 governments are required by domestic and/or international law to weigh family relationships when deporting non-citizens.

One immigrant, Hector J., who was deported from the United States away from his family in 2004, spoke about his loss of family in a way that summed up the sentiments of many others interviewed for this report. Hector spoke with a Human Rights Watch researcher by telephone, after he had been deported to Santo Domingo. Hector entered the United States at age 17 and lived with his mother in Brooklyn, New York. He attended public school in New York and completed an associate degree in human resources. After graduating, Hector worked as a community organizer and monitor for two non-profit organizations in Brooklyn that assisted homeless and low income families.149 Hector’s deportation separated him from his oldest daughter, Serena, and from his mother. He told Human Rights Watch,

[Y]ou know, being with your family, there is nothing that you can compare to anything in life. It’s just that warmness of the home, time with your loved ones

Ramon H. (introduced in Chapter IV), who was facing deportation for conviction of an aggravated felony, had such strong family ties to the United States that his attorney submitted a great deal of additional information to the court, even though the judge had no discretion to waive the deportation. Ramon’s wife told the court that her husband “is a wonderful and great husband and father to his two daughters. We both work to support our family … Our lives will not be the same if my husband is not with us. It will be very difficult for my daughters and myself.”151

Ramon’s daughter, Pamela Alicia, told the court, “My dad is the one who mainly supports the family. My father helps us when we need help on things like school and at home. My dad has given us everything we need to make us happy.”152 Pamela Alicia’s math teacher wrote a letter to the court, stating,

I am writing to respectfully request that [Ramon] … be allow[ed] to remain in the United States as a husband to his wife and as a father to [Pamela Alicia] and her younger sibling. In my experience with [Pamela Alicia], she has always been an excellent student … I must confess that a significant part of her growth as a thinker and student is due to the stability of her home …. It is rare to find a home environment that supports the student in the way that [Pamela Alicia] is supported.153

In another example, Jeremiah E., originally from Jamaica, came to the United States when he was eight years old as a lawful permanent resident and lived in California for 17 years. Jeremiah’s stepmother and father, both of whom are lawful permanent residents, petitioned to have him and his brother join the family. Jeremiah’s biological mother has not been involved in his life. Jeremiah’s other brother, his sister, two of his aunts, and two of his uncles are all US citizens.

Jeremiah was in detention in late 2006 facing deportation back to Jamaica for two offenses: possession of a controlled substance, for which he received 36 months of probation; and possession of a firearm, for which he also received 36 months of probation. Jeremiah’s stepmother wrote to the court,

[Jeremiah] and I always have [had] a great relationship, [when he was] a little boy we would go to Church together, and on our way we would sing songs from the tapes and at times we would just talk. As an only child for nine years we would do a lot of things together. When his sister was born he was excited and would help in many ways, the same with his brother. He is a loving son and brother and also helps around the home …. He also has a son of his own that he loves and adore[s]. We all love [Jeremiah], and I will continue to do so until God takes me home. I know he has made some wrong decisions, but I do hope that he has learned from them and … that he will be given another chance to be a positive leader both in the community and for his son.154

After Jeremiah’s son was born, he and his son’s mother lived in their own home together. During this time, Jeremiah worked as a carpenter, was a member of a union, and paid taxes for several years prior to his incarceration pending deportation. He was the sole financial support for his son and girlfriend. His father wrote, “I remember he would get up at four in the morning to fit in work and school into his day.”155 Jeremiah’s stepmother wrote,

All [Jeremiah] talks about is his son. Whenever he calls home, he asks about his son. It bothers him tremendously that he cannot take care of his son while he is detained. [Jeremiah] Jr. needs his father here—no one else can take a father’s place. If Jeremiah is deported, [Jeremiah] Jr. would be another child growing up without a dad. 156

Seventeen-year-old Michael Hinds, Jr. may lose his father, 58-year-old Michael Hinds, Sr., to deportation. At the age of 10, Hinds Jr. was reunited with his father because his dad returned to the United States after his mother, who was a lawful permanent resident, died of AIDS and he had no parent to raise him. Hinds Sr. returned to the United States from Jamaica after having already been deported in 1994 for attempted sale of a controlled substance in the third degree.157 He was facing deportation again for re-entering the country after deportation.

Speaking with obvious pride about his son’s academic and musical achievements (he is a pianist), Hinds Sr. told a Human Rights Watch researcher that he worked in construction, which he did in order to rent an apartment in the same neighborhood his wife had lived in, and to ensure his son’s attendance in school, and provide for him between 2000 and 2006.158 Hinds Sr.’s partner told a Human Rights Watch researcher that his son “is very obedient of his father. He never talks back to him. [Michael] tells his son to ‘try to keep his head up’ even though he’s been through so much and now his Dad is in detention. But it’s not easy. It’s not easy at all.”159

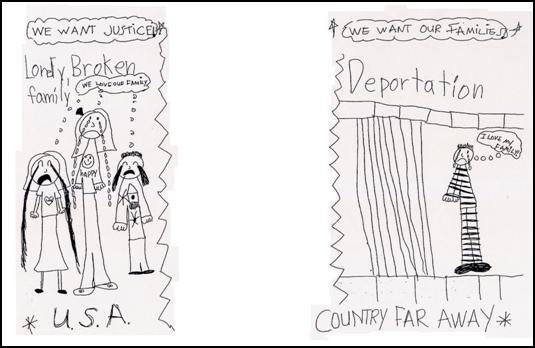

Drawing by a child facing separation from her father due to deportation © 2005 private

Cases like those described above, and in fact all such cases of family separation are particularly poignant because they are examples of families whose rights would have received greater protection when 212(c) hearings were still available.

Courts in the United States have been extremely reluctant to rely on international human rights law to overturn deportation decisions, even when family relationships are very strong and compelling. Few cases have looked at the human rights standards in detail, preferring to give these international treaties short shrift. However, the only US court to conduct a careful and thorough analysis of US human rights treaty obligations found that it would be inconsistent with those obligations to allow a deportation to go forward when it would interfere with the right to family unity. In Beharry v. Reno,160 Mr. Beharry, who entered the US from Trinidad as a lawful permanent resident when he was seven years old, had been ordered deported because of an aggravated felony conviction and denied a section 212(c) hearing as a result. He appealed that decision, raising the right to family unity under international law as a defense. The appellate court in the Southern District of New York highlighted Beharry's impending separation from several close family members, including his lawful permanent resident mother and his six-year-old US citizen daughter.

After considering several human rights instruments, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights as aids in interpreting US immigration law, the District Court found that “[s]ummary deportation of this long-term alien without allowing him to present the reasons he should not be deported violates the ICCPR's guarantee against arbitrary interference with one's family, and the provision that the alien shall ‘be allowed to submit the reasons against his expulsion.’”161 The Court further found that denial of a hearing balancing Beharry’s family ties “would violate the principles of customary international law that the best interests of the child must be considered where possible.”162

The US government appealed this decision. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the lower district court’s decision by finding that Beharry had not followed the correct procedures to raise the issues the district court considered. Therefore, the Court of Appeals did not address any of the international law issues; it declined to discuss “the merits of the district court's analysis of the interaction between international law, the Supremacy Clause, and § 212(h).”163

However, in later cases the Second Circuit rejected the reliance on international human rights law outright, holding that Congress's unambiguous intent controlled the availability of a waiver of deportation notwithstanding any perceived conflict with international law, customary or otherwise, of the sort discussed in Beharry.164 To date, no other US court has followed the District Court's reasoning in Beharry.165

Case Study: Loss of a Caretaker: Jimmy X.’s Story166

Jimmy X., originally from Laos, came to the United States with his parents as a refugee when he was four years old. His parents “made a little raft to cross the Mekong River [with] inner tubes and stuff like that.” Jimmy’s parents had difficulties adjusting to life in the United States. His father was “an abusive alcoholic. He used to beat my mom, me, and my sister up all the time.” Jimmy’s parents were divorced in 1989. His mother “would do that sweatshop stuff, you know making like five cents per item …. That’s why I really stick by her now, because I’m more mature now and I see all the struggle she did.”

As a teen growing up in Los Angeles, Jimmy joined a gang. He was 18 years old when he was convicted for robbery and home invasion, an aggravated felony. He was sentenced to seven years. In prison, Jimmy earned his GED. He told a Human Rights Watch researcher, “I used to get straight A’s when I was in school, so the GED wasn’t anything difficult …. Believe it or not, I was spelling bee champion in elementary school. Those were fun days, better days, best days.”

Jimmy told Human Rights Watch that after serving his criminal sentence (he was released after four years for good behavior) he had no idea that he would face deportation. He said, “I had my green card and everything, so I didn’t worry about it. This was the first time I ever heard anything about they’re deporting people. But that happens to everybody. You just don’t know until it happens to you.”

At the time of his interview with Human Rights Watch, Jimmy was a community outreach organizer for a non-profit group serving troubled youth involved in gangs. He explained,

“I really changed my life around. I don’t do anything bad anymore. I’ve been out five years, and I haven’t done anything illegal. I’ve made it a point to actually help others and prevent others from doing anything illegal. In the gang lifestyle you get used to doing things in certain ways … I’m working on my language right now, speaking in the best intellectual way. If only the government would actually see that some of us try so hard to change and do right.”

Although Jimmy has a final order of deportation, he has not yet been sent to Laos because the United States has not obtained the necessary travel documents. Jimmy has a lot of responsibility at work and at home. He cares for his mother and supports her. He told a Human Rights Watch researcher,

“[My mother] has suffered from depression and post-traumatic war, you know, stress. She is a little bit lost. I hate to say it, but she’s crazy. To the point where she always thinks someone’s after me. She really does think so. She thinks the phones are tapped and all that stuff. She got worse once I was put in deportation. She couldn’t understand. Because we’re here legally, she’s got all the paperwork and everything … She doesn’t leave the house at all, she doesn’t open the curtains, the lights are always off, she goes to the bathroom in the darkness … I use all my connections [from his work] to community agencies. That’s what pisses me off: I can help the whole damn world, but I can’t help my mom. I can’t get her like any government aid, anything like that.”

Jimmy barely speaks Laotian. When asked what would happen if he were sent to Laos, he said,

“My mom would go crazy. There would be no one here to take care of her. My sister can’t handle my mom. I mean, even I can’t handle her, but I still do my best with her. My mom can’t imagine me back there in Laos. She knows I’m an American boy. I mean, they didn’t give me a Lao name, they gave me an American name. Like any parents, they had all those hopes for me, for their kids.”

Children’s Rights

Beyond family unity in general, the rights of children to be raised by their parents is one of the strongest human rights counseling against the separation of families through deportation. Article 24 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which the United States is a party, entitles children “to such measures of protection as are required by [their] status as a minor, on the part of the family, society and the state.”

Article 9 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which the United States has signed but not ratified,167 requires that “States Parties shall ensure that a child shall not be separated from his or her parents against their will, except when … such separation is necessary for the best interests of the child.”168 Thus, the CRC weighs in favor of non-citizens’ rights not to be deported if it is contrary to the best interests of the child. Accordingly, the Committee on the Rights of the Child often notes concerns over states’ failure to put the best interest of children first and foremost in immigration proceedings.169

Almost every case study featured in this report presents an example of a family that was denied their right to remain together by US deportation policy. However, the following cases include particularly strong testimonies about the kinds of parent-child relationships that are harmed by deportation.

For example, eight-year-old Angelito Martinez is facing separation from his father, Eduardo. Eduardo explained his relationship to Angelito and his wife, Jennifer:

We used to do so many things together. I was his soccer coach at school. We would go fishing a lot. I took him to soccer, Jennifer took him to swimming lessons. I would help him with his homework. He is great at spelling. The school said maybe he should be in a higher grade, but I don’t want to do that right now. I think that’s too much pressure on him right now. As a family, we also ask him his opinion on decisions like that. The three of us talk about those decisions together. That’s why I don’t want to leave this country. My family. That’s it.170

Eduardo came to the United States at the age of 19. After several years in the United States, Eduardo said, “The most beautiful thing happened to me. I met my wife, Jennifer.” They were together for three years before getting married, and have been married for seven years. Eduardo and his wife applied to have his immigration status adjusted, but the paperwork was not final when he was arrested for possession of a marijuana joint and two grams of marijuana and for illegal possession of a weapon, which Eduardo said he “bought to protect my family. I kept it in the house, out of reach of my son. It is true that I smoked marijuana. I should not have done that. It’s shameful.” 171

Four-year-old Rosita and 10-year-old Carlos are facing separation from their father and stepfather, Miguel Y., who is currently in immigration detention waiting for deportation. His wife, Carmela Y., told a Human Rights Watch researcher, “[m]y son cries because he doesn’t understand why daddy disappeared.”172

Carmela was struggling to get by on her salary, to pay for rent, feed her two young children, and cover lawyers’ fees now that Miguel was in deportation proceedings. She explained that she couldn’t make ends meet on her salary alone:

I’m waiting for the tenth of the month. How can I help my kids? What will we eat for the next three days? Look—[she opens the refrigerator to show a Human Rights Watch researcher that it is empty apart from some milk and a half-eaten carton of fast food]—there’s nothing there! This is all I have to last us until I get paid again.173

Miguel had been convicted of possession of marijuana with the intent to sell, 174 and later in 1996 with receiving stolen property, an aggravated felony. His defense attorney advised Miguel to plead guilty in exchange for a 16-month sentence, without advising his client of the immigration consequences. Prior to his convictions, Miguel had lived in the country as a lawful permanent resident since the age of 13.

Deported to El Salvador, Miguel returned to the US in 1998, where he lived without getting in trouble with the law again (although his re-entry is a new deportable offense under immigration law). Miguel worked and supported Carmela, who was going to college to get her Bachelor’s degree when Miguel was arrested for illegal re-entry and detained. She explained what happened:

He got dragged out of the house in front of my two-year-old [Rosita]. He was handcuffed. [Rosita] put up a fight because she was … she didn’t want her daddy to leave.175

Losing a parent to deportation can be devastating for children, bringing about tragic results. Gerardo Anthony Mosquera, Jr., a US citizen, was the son of a 29-year-long legal permanent resident who was deported after committing the aggravated felony of selling a $10 bag of marijuana to an undercover police officer.176 Unable to be consoled after the loss of his father, Gerardo, a strong student interested in sports and taking care of his younger siblings, committed suicide by shooting himself in the head.

Ties to a Country

The US Supreme Court stated in Landon v. Plasencia that “once an alien gains admission to our country and begins to develop the ties that go with permanent residence his constitutional status changes accordingly.”177 Despite this accepted constitutional maxim, a non-citizen’s ties to the United States, including length of residence, military service, and business, educational, and community ties that are separate from family relationships, are often not considered when he or she faces deportation because of a criminal conviction.

Under human rights law, the state power of deportation should be limited if it infringes upon an individual’s right to a private life, which includes his or her ties to the country of immigration not including any family ties. Article 17 of the ICCPR provides that “[n]o one shall be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his privacy

The Human Rights Committee has explained that this “guarantee[s] that even interference provided for by law should be in accordance with the provisions, aims, and objectives of the Covenant and should be, in any event, reasonable in the particular circumstances.”179 Further, the committee has stated that the term “home” “is to be understood to indicate the place where a person resides or carries out his usual occupation.”180

Therefore, the right to protection against arbitrary interference with privacy and home encompasses those relationships and ties that an immigrant develops with the community outside of his or her family. For example, the Inter-American Commission has found that the right encompasses “the ability to pursue the development of one’s personality and aspirations, determine one’s identity, and define one’s personal relationships.”181

The European Court of Human Rights has weighed an individual’s ties to a country as a part of his private life (and separate from family life) in deportation cases. In C v. Belgium, the ECHR found that the petitioner’s private life included the petitioner’s “real social ties in Belgium”:182

He lived there from the age of 11, went to school there, underwent vocational training there and worked there for a number of years. He accordingly also established a private life there within the meaning of Article 8 (art. 8), which encompasses the right for an individual to form and develop relationships with other human beings, including relationships of a professional or business nature.183

The court ultimately found that the petitioner’s very serious crime outweighed countervailing factors, allowing him to be deported from Belgium, but only after a hearing that weighed his right to a private life against his crime. In another case, Beljoudi v. France, deportation was not allowed because of the rights violations faced by Mr. Beljoudi, including his right to privacy as well as his right to family unity. In the decision, one judge emphasized the right to privacy, finding that the applicant’s “links with France, and the absence of them with Algeria, are such that there must be much stronger arguments to justify an interference with his right to respect of his private life.”184 He continued,

[I]f there is a country responsible for the education and behavior of the applicant, there is room to consider that it is France, rather than Algeria. If it is not illegal, it is in any case morally rejectable to send to Algeria those of the numerous immigrants who become criminals, while those who contribute to the prosperity of the country can remain in France.185

Two additional cases, Moustaquim v. Belgium and Lamguindaz v. United Kingdom, involved non-citizens who the court found should not be deported because they had spent the vast majority of their lives in the host state, even though they had been convicted of various crimes as well.186 In each case, the individual had grown up and completed his education in the host state, which the ECtHR found constituted elements of his private life that required careful weighing prior to deportation.187

The European Union has taken steps to further codify the practice of weighing ties to a country before deportation by issuing a Council Directive on the issue in 2003. The Directive states that countries expelling long-term residents must take account of the length of their stay in the country when making a decision to expel188 and that long-term residents are entitled to “reinforced protection against expulsion.”189

Therefore, these international standards recognize that the right to private life is put at risk by deportation that fails to weigh the various ties and relationships that non-citizens develop with their host countries. In the United States, these ties and relationships can be subdivided into several parts, including: the length of legal residence in a country; military service in a country’s armed forces; legal residence in a country since childhood; and economic and business ties.

Length of Legal Residence

Many immigrants facing deportation from the US have stronger ties to the US than to their countries of origin, but unlike in Europe these ties receive no consideration in deportation proceedings. For example, 35-year lawful US resident and Cuban national, Sergio C., came to the United States at the age of six. His entire family190 was admitted into the United States, which gave Sergio legal permission to remain in the country. He attended school through the 10th grade in Miami, Florida. After leaving high school, he went to work for the Continental Marketing Group, where he was employed for 20 years, and paid income tax. Sergio pled guilty to two acts of fraud, for which he received a sentence of 20 months imprisonment and was required to pay restitution. He wrote to Human Rights Watch,

I have entered my plea and served my punishment. I only wish to return to the community from which I was raised to be the man and father I am known to be.191

Jared L., originally from Jamaica, entered the United States as a lawful permanent resident in 1972, which was 34 years prior to his arrest in 2006. He worked for a construction company for most of his adult life, and is facing deportation for unlawful transport or sale of a controlled substance, and aiding and abetting that transport or sale. Jared L. wrote to Human Rights Watch from immigration detention, “I have no one in Jamaica, all my family are here in the states.” Prior to his arrest and detention, Jared L. was injured on the job and was receiving treatment for five degenerated discs in his lower back. Now in immigration detention in Los Angeles, Jared is confined to a wheelchair. His treatments are paid for by the insurance of his employer, which “does not cover [him] outside of California, much less outside of the U.S.A.”192

Legal Residence in the United States Since Childhood

The international definitions of private life embrace the ties and relationships that a person builds with his or her country of immigration. Non-citizens who have lived in the United States from a very young age have developed a particularly strong connection to the country; nevertheless, these ties are given no weight in deportation hearings.

For example, Chris L. was born in a Cambodian refugee camp in Thailand and entered the United States legally as a refugee with his entire family when he was just three months old. However, Chris was charged and tried as an adult with attempted murder at the age of 15, convicted at age 16, served 10 years in prison, and now faces deportation to Cambodia.193

He told a Human Rights Watch researcher about his early childhood in the United States. Chris and his mom, dad, grandmother, and two sisters first lived in Dallas, Texas, and soon moved to Napa, California. His life in Napa was “good, normal. I was a regular American boy.” Then when Chris turned 12, his family moved to Riverside, California, where he “started hanging out with the wrong people.”194

Once in Riverside, Chris had friends who were gang members. On the night of his crime, he told a Human Rights Watch researcher, he had “tried to scare someone by shooting in the air. But no one was even hurt in my crime. I never should have taken the deal for attempted murder. I was only age 15. I did 10 years. My mistake was not thinking right at age 15, but I’m 25 now.”195 Chris said, “I didn’t know anything about being deported. Then, after serving my 10 years, immigration came to get me. My family is devastated. My grandma had a mild heart attack. Everyone in my family is afraid for me if I go back to Cambodia.”196

When asked what he would do if he wasn’t deported, Chris said, “I want to start a fresh life. I would like to study biology and psychology. I got my GED in prison. I have a certificate in computer repair. My sister would let me move in with her in Riverside. I know I could do it.”197 During his incarceration in California, Chris’s entire family—his mother, father, sister, and brother—all became US citizens.

Case Study: “I am Legally Here”198

Lan X. was brought to the United States when he was four years old. He was convicted of second degree murder at the age of 16 and sent to prison in California. Lan’s crime was gang-related, in which he shot a rival gang member who had shot at his house and assaulted his cousin. After serving his sentence in prison, Lan was facing deportation. Ironically, Lan’s parents are actually Laotian, but he was born in Cambodia, and so Lan faces deportation there even though he does not speak Khmer. He explained to a Human Rights Watch researcher about his family circumstances at the time of his offense:

“Before I joined the gang, I used to look at my mother and I just didn’t want to be at home because it would be a burden to my family. I said, ‘Okay [the gang will] take care of me, they feed me, they bathe me, they watch me. . .’ [It was] the worst mistake I ever did in my life. I thought, ‘My family—I’ll just leave them alone where you don’t have to worry about having to spend the extra money just to help me out.’ I felt like I was a burden to my family and plus, my mom was just a single mom. She came here with no education. She couldn’t do anything.”

After serving eight years in prison for his crime, Lan was shocked to learn he would be deported to Cambodia. He explained,

“I understood about illegal immigration, but I thought ‘your honor, that is not pertaining to me.’ I am not an illegal immigrant. I am legally here and a permanent resident here. Also, I didn’t think I was considered an adult. I was 16. But none of that mattered. I was convicted as an adult and now I’m being deported even though I thought I was a lawful permanent resident. Do you think as a 16-year-old I could have said to my mom, ‘Hey, Mom, you need to go to an INS place to get your citizenship?’ Do you think a 16-year-old would think of that? If you think a 16-year-old would think of that and should be tried as an adult, then you might as well think that an 11-year-old should drink beer.”

Lan said he knew his crime was horrible, and one that he deserved punishment for, but he emphasized the fact that he pled guilty to his crime, served his eight-year sentence, and that “it didn’t take me two or three times [to learn my lesson], it took me once in my life. When I was incarcerated, I went and got my education, my high school diploma, and then I got my college degree. I always worked two or three jobs. But that doesn’t matter. That’s how society is right now, all they judge you for is what happened in the past. They won’t judge you for who you are now.”

Lan was under a final order of deportation when he was interviewed by Human Rights Watch, but he had been released on parole while the immigration authorities tried to make travel arrangements to send him to Cambodia. When he is deported to Cambodia (or Laos), Lan will leave behind two brothers and two sisters. Lan was using his time on parole pending deportation to work to help his siblings and nieces and nephews out financially.

“I work as much as I can ’cause I’m the oldest one in the family. I try to take care of them as much as I can. I want to be married too one of these days, but the only thing that scares me is what happens if they take me away? If I have to tell my girl, how are you going to survive? Can you fend for yourself? And what happens if I have kids? Who’s going to take care of my daughter or my son when I’m in Cambodia? And what am I gonna do in Cambodia? They might as well send me to the gas chamber or to shark infested waters. I’m more Americanized. I don’t even speak their language!”

Reflecting on his crime and on his pending deportation, Lan concluded, “I did the crime, I knew I had to do the time, but with immigration law and everything around it, it’s like a chain reaction. I didn’t know. But it’s all too late now to rewind back time.”

Military Service

Military service is another example of an individual’s ties to the community. Like schooling, work experience, and friends, it is one of the elements of an individual’s private life which ought to be weighed prior to deportation.

Forty-two-year-old Andre R. has lived in the United States as a lawful permanent resident for 36 years. He entered the country when he was five years old. Andre attended public school throughout his childhood and entered the US military upon graduation from high school. He served in the US army in Panama in 1982 and 1985. Upon leaving the army in 1986, he applied for US citizenship but says that he never received the notice of his citizenship hearing. As a result, he was recorded as failing to appear for the hearing, although he remained a lawful permanent resident. Then, in 1995 he pled guilty to an aggravated felony that rendered him deportable once the immigration laws were changed in 1996. He explained that he pled guilty “thinking that it was the best for me so I could go to work and not miss any time … I should be able to be home with my family199 working and doing what a man is to do to take care of his children.”200

Andre owned his own company in the United States. As he wrote to Human Rights Watch, “I have paid tax all my life to this country until DHS detained me.” He concludes, “All I ask for is a fair chance to fight for what is right and that is my family and my right to be in a country that I fought for in the military. When I joined the army they never asked me if I was an alien.”201

A second example is that of Joe Desiré, originally from Haiti, who has lived in the United States as a lawful permanent resident for 40 years, since he was 11 years old. Desiré was married in 1971, and has four United States citizen sons, two of whom are in the military. Desiré himself was in the US military from 1970 to 1974. He was based in North Carolina, Oklahoma, Fort Dix, Okinawa, Panama, Korea, and did a one-month tour of duty in Vietnam. Desiré told a Human Rights Watch researcher that during his years in the military he developed the habit of using “marijuana, acid, and sometimes cocaine.”202

Desiré admits that it was his drug habit that caused him to get in trouble with the law. He has two drug possession convictions and one drug sale conviction—all from the mid-1990s—for which he served his criminal sentence, and now was facing deportation back to Haiti, a country in which he has no family or contacts. He told a Human Rights Watch researcher, “What I know of Haiti, I’ve read. I know nothing of the place. Nothing.”203

Despite his drug habit and three convictions, Desiré worked his entire life. He was a welfare fraud investigator and went to college at night after leaving the military. He explained, “my intention was to go into law enforcement, but then I got into my own business. I became a certified cable technician and worked for HBO, and NACOM, and as a sales manager for American Cable Systems. I also worked on the side as a limo driver.”204

As of this writing, Desiré has spent eight years in immigration detention awaiting deportation to Haiti. He told a Human Rights Watch researcher, “I have lived here most of my life. I want to be in touch with my sons. I have been clean and sober now for ten years. I cannot see myself going back to that style of life.”205

Training and Employment

International human rights law emphasizes the importance of education, vocational training, and employment in a host country “for a number of years” as elements of an individual’s private life placed at risk by deportation.206 These factors receive no consideration in US deportation law.

For example, Lingyan Zhuang, originally from China, owned his own store in Highland Park, Illinois, and had lived in the United States as a lawful permanent resident since the 1980s. He pled guilty in 2003 to illegally smuggling family members into the United States, for which he served 15 months in prison. Zhuang’s crime made him deportable. Zhuang’s wife is a naturalized US citizen and the couple has two US citizen children. The cost of fighting her husband’s deportation has caused her to work seven days a week at the couple’s store. Zhuang’s attorney said, “[a]ny American who sees the case, sees his children here and his family here, would decide that he’s someone who should not be deported. As the whole town of Highland Park has decided by their strong support … he’s someone who benefits the community, and we need people like him here.”207

Non-citizens who reside in the United States for a significant amount of time have deep ties to the country that extend beyond their immediate families. Once a non-citizen establishes a lengthy residence in the United States, the impact of deportation without a balancing hearing can produce a devastating violation of the right to private life.

Protection from Return to Persecution for Refugees

The principle of non-refoulement places well recognized limits on states’ powers to deport refugees. The 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, to which the United States is a party, binds parties to abide by the provisions of the Refugee Convention, including that no state “shall expel or return (‘refouler’) a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.”208

Given the imperative of protecting refugees from return to a place where they would likely be persecuted, refugee law permits a very narrow exception to non-refoulement, which only applies in extremely serious cases. Article 33(2) of the Refugee Convention states that protection against refoulement may not be claimed by a refugee, “who, having been convicted by a final judgment of a particularly serious crime, constitutes a danger to the community of that country.”209

Procedures must be in place to ensure careful application of this narrow exception. The Refugee Convention and Protocol require that a refugee should be “allowed to submit evidence to clear himself, and to appeal to and be represented for the purpose before competent authority or a person or persons specially designated by the competent authority.”210 UNHCR’s Executive Committee has explained that deporting a refugee under Article 33(2) “may have very serious consequences for a refugee and his immediate family members … [and therefore should only happen] in exceptional cases and after due consideration of all the circumstances.”211 The exceptions to non-refoulement in Article 33(2) were intended to be used only as a “last resort” where “there is no alternative mechanism to protect the community in the country of asylum from an unacceptably high risk of harm.”212

Therefore, an individualized determination must occur before deportation in compliance with Article 33(2),213 during which states must weigh two elements: that a refugee has been convicted of a particularly serious crime and that he or she constitutes a danger to the community.214

With regard to the first prong of the inquiry, the determination of a particularly serious crime cannot be merely rhetorical: It requires that the crime in question be distinguished from other crimes.215 The UNHCR has defined such a crime as a “capital crime or a very grave punishable act.”216

With regard to the second prong, a government must separately assess the danger the individual poses to the community: “A judgment on the potential danger to the community necessarily requires an examination of the circumstances of the refugee as well as the particulars of the specific offence.”217

Thus, under the Refugee Convention, even individuals convicted of serious crimes are guaranteed the right of a hearing to show that they do not in fact pose a danger to the community. Indeed, the “danger to the community” exception “hinges on an appreciation of a future threat from the person concerned rather than on the commission of some act in the past.”218 Past criminality is not per se evidence of future danger.219

Unfortunately, US law falls short of these standards, which are binding on the United States because of its ratification of the Refugee Protocol. The less protective standard used by the United States is known as “withholding.” Withholding states that protection may not be claimed by a refugee, who “having been convicted by a final judgment of a particularly serious crime is a danger to the community of the United States,"220 and a subsequent section states that for purposes of interpreting this clause,

[A]n alien who has been convicted of an aggravated felony (or felonies) for which the alien has been sentenced to an aggregate term of imprisonment of at least 5 years shall be considered to have been convicted of a particularly serious crime. The previous sentence shall not preclude the Attorney General from determining that, notwithstanding the length of sentence imposed, an alien has been convicted of a particularly serious crime.221

As this section states, in addition to all refugees convicted of aggravated felonies with five year sentences, the Attorney General has statutory authority to send refugees to persecution with sentences of less than five years. In a decision under this statutory authority, the Attorney General has issued the blanket statement that aggravated felonies with sentences of less than five years “presumptively constitute particularly serious crimes,” meaning that the non-citizen would have the difficult burden of overcoming the Attorney General’s presumption that his or her crime was “particularly serious” in deportation procedures.222

The automatic nature of this bar to refugee protection without judicial scrutiny of the details of the particular crime committed or the nature and likelihood of persecution feared violates the standards provided in international law for two reasons. First, it fails to weigh individually the seriousness of the crime. Second, it fails to assess whether the potential deportee poses a risk of dangerousness to the community of the United States. In sum, it fails to protect refugees from return to persecution and to carefully and narrowly apply the exception to this standard. The US is therefore regularly violating its obligations under international refugee law.

Juan Ramirez,223 a gay man originally from Guatemala, was tortured, detained arbitrarily, and raped prior to fleeing his country in 1992. Since 1998 he had been working in the United States under a valid work visa until he was placed in removal proceedings after being convicted of possession for sale of a small quantity of methamphetamine. The immigration judge in his case found that his conviction constituted a particularly serious crime, and therefore barred him from applying for withholding of removal. Ramirez claimed he feared persecution because of his status as a gay man, and because of his previous experience of persecution in Guatemala. His case is currently under appeal to the Board of Immigration Appeals.224

In another example, Mark McAllister, originally from Northern Ireland, was barred from protection against return to persecution because of his conviction for three counts of possession with intent to distribute the drug known as ecstasy. McAllister’s fear of persecution was based on his family’s political opinion in Ireland. His father was repeatedly arrested, beaten and jailed by the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) for his activities with the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA). His mother was also repeatedly arrested. Soon after the RUC’s security files on the McAllisters ended up in the hands of paramilitaries, the family’s house was repeatedly shot at while the family was at home. The pattern matched other cases of murders of INLA members and their families in Ireland. McAllister’s parents feared for their lives and were warned to leave the country, which they did: while McAllister was still a juvenile in 1996, they legally entered the United States. After his conviction, McAllister asked the immigration judge, the BIA, and the district court to grant him withholding of removal, but all three levels of review determined that his conviction was an aggravated felony and a particularly serious crime, which barred him from protection against return to persecution.225

98 UN Human Rights Committee, General Comment 15 (“It is in principle a matter for the State to decide who it will admit to its territory. However, in certain circumstances an alien may enjoy the protection of the Covenant even in relation to entry or residence, for example, when considerations of non-discrimination, prohibition of inhuman treatment and respect for family life arise”); Inter-American Commission on Human Rights – Report No. 49/99 Case 11.610, Loren Laroye Riebe Star, Jorge Alberto Barón Guttlein and Rodolfo Izal Elorz v. Mexico, April 13, 1999, Section 30 (recognizing state authority to control immigration but stressing that this power is limited by the American Convention on Human Rights’ guarantees); Gerald P. Heckman, “Securing Procedural Safeguards for Asylum Seekers in Canadian Law: An Expanding Role for International Human Rights Law?” International Journal of Refugee Law, vol. 15 no. 2 (2003), p. 214 (“[o]nce widely accepted as a nearly unfettered discretion derived from state sovereignty, the power of states to control the entry and residence of aliens on their territories is increasingly understood to be circumscribed by domestic law and customary and conventional international law.”); Boughanemi v. France (App. 22070/93), Judgment of 24 April 1996 (recognizing that a state’s right to control immigration is “well-established international law,” but that it must be tempered by Article 8’s protection of family life).

99 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), adopted December 16, 1966, G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI), 21 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 16) at 52, U.N. Doc. A/6316 (1966), 999 U.N.T.S. 171, entered into force March 23, 1976, ratified by the United States on June 8, 1992, http://www.ohchr.org/english/countries/ratification/4.htm (accessed May 30, 2007).

100 ICCPR, art. 13 (emphasis added).

101 UN Human Rights Committee, General Comment 15, paras 9 and 10.

102 American Convention on Human Rights "Pact of San Jose, Costa Rica,” General Information on the Treaty, http://www.oas.org/juridico/english/Sigs/b-32.html (accessed May 30, 2007).

103 American Convention, art. 8(1).

104 Inter American Commission on Human Rights, Report No. 49/99 Case 11.610, Loren Laroye Riebe Star, Jorge Alberto Barón Guttlein and Rodolfo Izal Elorz v. Mexico, April 13, 1999, Section 70-1.

105 Non-citizens convicted of aggravated felonies who are not lawful permanent residents, or who have lawful permanent resident status conditionally, are subject to accelerated removal procedures without a hearing before an immigration judge. Under such procedures, the law explicitly states that “an alien convicted of an aggravated felony shall be conclusively presumed to be deportable from the United States.” 8 U.S.C. Section 1228. Where cases are reviewed by immigration judges or the Board of Immigration Appeals, serious concerns exist that the quality of such review has “fallen below the minimum standards of legal justice.” Benslimane v. Gonzales, 430 F.3d 828, 830 (7th Cir. 2005). Review of detention and removal decisions is now possible only through a writ of habeas corpus in the Court of Appeals, and it is unclear as yet whether such review will be construed to include the right to challenge the underlying removal decision itself. Hiroshi Motomura, “Immigration Law and Federal Court Jurisdiction Through the Lens of Habeas Corpus,” Bender's Immigration Bulletin, vol. 11-10, p. 2 (2006). In addition, all categories of aggravated felons (including lawful permanent residents) facing deportation have no right to raise the fact that they will be separated from family members if the deportation is carried out. This lack of a hearing violates basic standards in international human rights law.

106 European Court of Human Rights, Al-Nashif and Others v. Bulgaria (App. 50963/99), Judgment of June 6, 2002.

107 Ibid., Section 137.

108 Stewart v. Canada, Communication No. 538/1993, U.N. Doc. CCPR/C/58/D/538/1993 (1996).