V. Failure of Justice

He was just a boy. I want to know what they did with him.

—Darshan Kaur, mother of victim

The cases detailed in this chapter highlight different aspects of the impunity that has prevailed since the Punjab counterinsurgency operations from 1984 to 1995. These cases reflect the failure of various government institutions including the police, the judiciary, the Central Bureau of Investigation, and the National Human Rights Commission to ensure accountability and redress for gross human rights violations.

Many observers had hoped that the Punjab mass cremations case described in detail immediately below would redress the systematic “disappearances” and extrajudicial executions perpetrated by Indian security forces. After 11 years of proceedings that have excluded victim participation, relied solely on police admissions, failed to identify responsible officials, and offered only limited compensation to a small subset of victims' families, many victims’ families now feel the government condones the abuses and the denial of justice.

Another case detailed below, that of murdered human rights defender Jaswant Singh Khalra, demonstrates the hurdles families face in pursuing individual cases, as well as the government’s reluctance to pursue investigations and charges against the alleged architects of these systematic abuses. This case, and the others we discuss in this chapter, highlights biases within the prosecuting authority, the challenges brought on by prolonged trials, the police’s role in the destruction of evidence and fabrication of records, and police intimidation and abuses suffered by survivors of those killed by the police.

In each case, the families continue to call for justice for the “disappearance” or extrajudicial execution of their loved one. These families have stated that they cannot move forward in their lives without knowledge, justice, and reparations.

A. NHRC and the Punjab mass cremations case

Human rights groups have uncovered basic facts of the gross human rights violations perpetrated by Indian security forces in Punjab during the counterinsurgency, including details of the destruction of evidence through thousands of secret cremations. In 1996, after reviewing evidence of mass cremations, the Supreme Court appointed the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) to address these violations.

During the past decade of the proceedings before the NHRC, the Commission has failed to apply Indian or international human rights standards to investigate and provide proper reparations for these abuses. Although the NHRC has failed to provide a remedy for these abuses, because the Supreme Court retains jurisdiction in this case and will review the NHRC’s actions, it will provide the ultimate resolution of the mass cremations case that will set a precedent in India on redressing mass state crimes.

In 1995, after human rights activist Jaswant Singh Khalra released official records exposing the mass secret cremations perpetrated by the Punjab police in Amritsar district, the Committee for Information and Initiative on Punjab (CIIP) moved the Supreme Court to demand a comprehensive inquiry into extrajudicial executions throughout Punjab.82 After Punjab police “disappeared” Jaswant Singh Khalra, the Supreme Court eventually ordered the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), India’s premier investigative agency, to investigate these crimes.83

The CBI submitted its final report on December 9, 1996,84 limiting its investigations to Amritsar district. The CBI’s report, which the Supreme Court sealed, listed 2,097 illegal cremations at three cremation grounds of Amritsar district—then one of 13 districts in Punjab.85 Khalra himself, however, had discussed over 6,000 cremations in Amritsar district.86 Moreover, CIIP had stated in its original writ petition that interviews with cremation ground workers disclosed that multiple people were often cremated with the firewood normally required for completely burning one body.87 Thus, many more than 2,097 bodies could have been cremated.

In December 1996, the Supreme Court referred the mass cremations case to the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC or “Commission”), observing that the CBI’s inquiry report disclosed a “flagrant violation of human rights on a mass scale.” In this case, the Supreme Court appointed the NHRC as its sui generis body, with the extraordinary powers of the Supreme Court under Article 32 of the Indian Constitution to redress fundamental human rights violations. The Supreme Court requested the NHRC “to have the matter examined in accordance with law and determine all the issues which are raised before the Commission by the learned counsel for the parties,” and also ordered that any compensation awarded by the NHRC would be “binding and payable.”88 Thus, the NHRC had the powers to forge new remedies and fashion new strategies to enforce fundamental human rights.89

The Supreme Court also entrusted the CBI with investigations into the culpability of police officials in the secret cremations case,90leaving “all the issues which are raised before the Commission” to the NHRC.91

Unfortunately, throughout the decade-long proceedings, the NHRC ignored the fundamental rights violations that had occurred in Punjab and thus shielded perpetrators from accountability. It refused to allow a single victim family to testify and failed to conduct any independent investigations towards identifying responsible officers. Instead, the NHRC based its findings on information provided by the Punjab police, the perpetrators of the crimes. Furthermore, the Commission refused to consider mass cremations, extrajudicial executions, and “disappearances” throughout the rest of Punjab. Despite having wide powers under Article 32, the NHRC’s actions were restrictive even when compared to steps it has taken in other cases under its normal limited powers. For example, the NHRC has often sent its own investigatory teams sua sponte to examine violations based on news reports, and has even filed lawsuits to challenge judgments and request the transfer of trials relating to the Gujarat pogroms.92

In its over ten years of proceedings in the Punjab mass cremations case, the NHRC compensated the next of kin of 1,051 individuals for the wrongful cremation of their loved ones, where the Punjab police did not follow the rules for proper cremations, and 194 individuals for the violation of the right to life, where the Punjab police admitted custody prior to death but did not admit liability for the unlawful killing.

In October 2006, the NHRC appointed retired Punjab and Haryana High Court Justice K.S. Bhalla as a commissioner for conducting an inquiry in Amritsar (“Bhalla Commission” or “Amritsar Commission of Inquiry”) to identify the remaining cremation victims from the CBI list under its consideration, if possible, within eight months.93

From 1997 to 1999, the Punjab mass cremations litigation stalled over the powers of the NHRC to adjudicate the case. The main question was whether the Commission possessed the Supreme Court’s powers under Article 32 of the Constitution, or if the Commission was bound by the act that created it, the Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993 (PHRA).94 The PHRA limits the Commission’s oversight in its regular operations to violations that occurred within a year of the filing of the complaint, grants only recommendatory powers to the NHRC, and prevents it from investigating abuses by armed forces, among other restrictions.95 In August 1997, the NHRC stated that it possessed the court’s Article 32 powers in this case, quoting a key Supreme Court case on Article 32:

We have therefore to abandon the laissez faire approach in the judicial process particularly where it involves a question of enforcement of fundamental rights and forge new tools, devise new methods and adopt new strategies for the purpose of making fundamental rights meaningful for the large masses of people...

It is for this reason that the Supreme Court has evolved the practice of appointing commissions for the purpose of gathering facts and data in regard to a complaint of breach of a fundamental right.96

That same day, the NHRC issued a second order on proceedings, proposing the invitation of claims by public notice and inquiries “to ascertain whether the deaths and subsequent cremations or both were the results of acts which constituted violation of human rights or constituted negligence on the part of the State and its authorities.”97The Union of India litigated the NHRC’s powers back to the Supreme Court, challenging its jurisdiction over the mass cremations case.98 In 1998, the Supreme Court held that in the Punjab mass cremations case, the NHRC possessed the court’s Article 32 powers, the NHRC was not limited by the Protection of Human Rights Act, and the Supreme Court retained final jurisdiction over the case.99

Although this order meant that the NHRC was fully equipped to investigate the widespread and systematic human rights abuses that had occurred throughout Punjab because it possessed the extraordinary powers of Article 32, in January 1999, the NHRC pronounced an order on the scope of its inquiry, limiting itself to the 2,097 cremations stated by the CBI to have occurred in three crematoria in Amritsar district, and divided the cremations into three lists of identified, partially identified, and unidentified cremations.100 The limited mandate meant the NHRC would only consider victims of unlawful killings whose bodies were: (1) disposed of through cremation, and not other methods; (2) cremated in one of the three crematoria investigated by the CBI in one of then 13 districts in Punjab; (3) cremated between 1984 and 1994; and (4) included in the CBI’s list of 2,097 cremations.

The CIIP challenged this restriction several times before the NHRC and ultimately to the Supreme Court.101 The NHRC insisted on its limited mandate and the Supreme Court refused to intervene at that stage.102 The NHRC thus ignored its Article 32 powers in this case.103

Throughout the entire proceedings, the NHRC refused to investigate a single case of illegal cremation.104 It relied solely on the accused—the Punjab police—to provide or confirm identification information on victims of illegal cremations. Even in cases where CIIP submitted identification information on partially identified or unidentified cremations, which it had derived by correlating the information available on the death with its database of “disappearances” and extrajudicial executions, the NHRC accepted the identification only if it was confirmed by the Punjab police.105 Only in one case did the NHRC reject the police version of events based on inconsistencies between an affidavit by the Punjab police and a petition filed by the state of Punjab concerning the same cremation.106

The NHRC also relied on the police to determine the type of violations. Only where the police were willing to admit custody of the victim prior to his or her death, did the Commission find a violation of the right to life based on the principle of strict liability.107 The Punjab police never admitted to direct liability or responsibility for violating anyone’s rights, including victims’ right to life or liberty, and continued to maintain that the victims were mainly terrorists or criminals killed in cross-fire.108 The NHRC identified 194 such cases out of the list of 2,097 cremations.109

Where the police denied they had prior custody of the victim but acknowledged that they had illegally cremated the person—in 1,051 cases—the NHRC found that the dignity of the dead had been violated.110 In determining the violation of the dignity of the dead, the NHRC relied primarily on the solicitor general’s admission that the Punjab police had not followed the rules for cremating unidentified bodies.111 Of the original lists drawn up by the CBI, 814 cremation victims remained unidentified, and an additional 38 cases were excluded as duplicates identified by the state of Punjab.112These victims were passed to the Amritsar Commission of Inquiry for identification by the NHRC’s October 9, 2006 order.113 The Bhalla Commission subsequently reduced this list to 800 cremations, based on submissions by the Punjab police.

In no case did the NHRC accept testimony from family members or witnesses, despite the drastically differing accounts put forward by the families and the accused. Nor did the NHRC accept challenges to the police version of events, based on victim testimony.114 It relied on the Punjab police for the identifications despite several troubling indications of lack of trustworthiness and impartiality, not surprising considering that the Punjab police was investigating its own colleagues. The NHRC itself found a serious lapse by the Punjab police for obviously concealing information at the time of cremation, and only revealing that information years later in litigation—as evidenced by their subsequent ability to identify 663 victims of illegal cremations during the proceedings before the NHRC.115

The NHRC failed to challenge the police version of events despite police admissions of forging the identities of its cremation victims. In February 2006, Punjab state officials admitted that the Punjab police had forged the identities of cremation victims in order to protect over 300 police informants living under assumed identities.116 The informants were alleged to have been killed in police encounters and cremated as unidentified bodies. However, these informants were given new identities and innocent individuals were killed and cremated in their place. This admission means that the true identities of the cremation victims cannot be established until the Punjab police reveals the identities of the victims killed and cremated in lieu of the informants.117

The CIIP demonstrated to the NHRC that the Punjab police had fabricated at least one identification when the next of kin of the decedent admitted to Ensaaf that his father, the alleged secret cremation victim, a former police officer, had died of natural causes at home. A police contact, offering compensation, encouraged him to agree to having his father identified as a victim of a secret cremation.118 When the CIIP presented this information at a February 2007 hearing of the NHRC, after some argument, the Chairperson instructed the state, which had submitted the incorrect identification, to re-investigate only that identification.119 At the subsequent hearing, the state submitted that it had made a mistake in the identification.120 The NHRC has not yet pronounced a ruling on this issue.

Throughout the proceedings, the NHRC has failed to investigate the illegality of individual killings, the role of state security forces or their agents in planning or carrying out illegal killings, other rights violations suffered by family members, or the identities of individual perpetrators, among other issues. Instead, in its orders granting compensation, the NHRC repeatedly stated that it was not expressing any opinion regarding culpability or responsibility for even the limited rights violations that it had identified.121 The NHRC maintained that it did not want to prejudice the investigations being carried out by the CBI.122 While the NHRC was not specifically instructed to establish criminal liability, under its Article 32 mandate, it was empowered to conduct detailed investigations capable of establishing the rights violations perpetrated as well as the identity of the responsible officials. In fact, in its August 1997 order, the NHRC had held that it would award compensation “only after the factual foundations are laid establishing liability.”123

The NHRC acted without regard for individual liability with its August 2000 order on 88 claims. In its submissions before the NHRC, the state of Punjab proposed awarding compensation to only 18 of the 88 claimants, with no admission of liability or guilt. The NHRC endorsed the proposal by the state:

For this conclusion it does not matter whether the custody was lawful or unlawful or the exercise of power of control over the person was justified or not, and it is not necessary even to identify the individual officer or officers responsible/concerned.124

All of the families submitted affidavits through CIIP rejecting any proposed compensation, stating that arbitrary cash doles did not meet their expectations of justice.125

The NHRC has used the principle of strict liability to attribute liability to the state, ignoring the individual actors. Thus, based on the principle of strict liability rather than any findings of wrongdoing by specific officials, the state was ordered to pay compensation to 194 individuals for violating their right to life, and to 1,051 individuals for violating the dignity of the dead.126 The use of strict liability resulted in the preclusion of investigations, where the establishment of direct liability was possible. For example, in many cases, the records of the cremation grounds identified the police station and officer who deposited the body for cremation. Thus, the perpetrators of the illegal cremation were identifiable and the Commission should have held them directly liable. However, the NHRC’s application of strict liability with the total exclusion of direct liability, combined with the ineffectiveness of CBI prosecutions, has resulted in de facto impunity for the perpetrators.

Developing a comprehensive reparations policy requires extensive investigation to clarify the extent of human rights violations, the potential beneficiaries, and the nature of injuries suffered, among other issues. International law identifies various methods of reparations, as discussed above. The NHRC has not come close to meeting this standard. Instead it has offered an arbitrarily determined amount of money only to a small subset of victims’ families. Given the NHRC’s failures to establish what happened to their loved ones or to identify the security officers responsible for abuses, many families who have been offered compensation, moreover, have perceived the offer as an attempt to buy their silence.127

In its first major compensation order in November 2004, the NHRC quoted Supreme Court precedent which stated that the amount of compensation depended on the facts of each case.128 The NHRC asserted, “Indeed, the quantum of compensation depends upon the circumstance of each case and there is no rule of thumb which can be applied to all cases nor even a universally applicable formula.” This reiterated a holding from the NHRC’s August 1997 order where it stated, “Indeed the question of quantification of compensation will arrise [sic] only after the factual foundations are laid establishing liability and, only thereafter, the questions of quantification follow.”129 Notwithstanding this precedent, the NHRC proceeded to award the same lump sum in every case in which the Punjab police admitted having had custody of the victim prior to the cremation.130 It subsequently defined “factual foundations” to mean the violation of the dignity of the dead as a result of the unlawful cremation, not the “manner and method of killing.”131 Thus, in over 10 years of proceedings, the Commission was not able to establish any new factual foundations; the fact of illegal cremation had been established by the CBI and Supreme Court in 1996.

CIIP solicited the intervention of international human rights groups to demonstrate the need to investigate the violations of the right to life and the physical and psychological trauma suffered by victims’ family members. Without such an understanding, the NHRC would not be able to develop or provide meaningful reparations. During a ten-day evaluation of 127 families in May 2005, organized by Ensaaf, experts of the Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) and the Bellevue/NYU Program for Survivors of Torture (Bellevue) assessed the torture and trauma suffered by families of some of the “disappeared” and extrajudicially executed persons, whose cases were part of the Punjab mass cremations case before the NHRC. The expert report submitted at the NHRC hearing on October 24, 2005, demonstrated that the deprivation of life occurred within a pattern of violations that included intentional abuse of multiple family members of the “disappeared” or extrajudicially executed person. The PHR/Bellevue evaluation found alarming rates of current and past psychological and physical suffering among the family members.132 The CIIP called on the Commission to summon the authors of the report to testify.133

The Commission rejected the report and attacked the authors’ professional credibility.134 The Commission did not attempt to resolve any of the objections it discussed in its order, in writing or at the multiple hearings that occurred between the report’s submission in October 2005 and the order issued regarding the report in October 2006. PHR and Bellevue responded to the NHRC’s order with an open letter in December 2006. 135

In its last major order on October 9, 2006, the NHRC dismissed CIIP’s arguments regarding the development of a comprehensive reparations program. The NHRC stated that it was sure the state of Punjab was fulfilling its obligations, and the NHRC did not feel compelled to make an order:

[T]he Learned Solicitor General stated that the State of Punjab had been taking all such steps as are necessary to heal the wounds of the effected families….It is an obligation of every civilized State to ensure that its acts, which have been found to be violative of humanitarian laws and/or which impinge upon human rights of the citizens, do not reoccur. We have no doubt that the State of Punjab as well as the Union of India are alive to their obligations in this behalf and would take appropriate steps which would also restore institutional integrity. We have also no doubt that the State of Punjab would offer medical/psychological assistance to a member/members of any such family which has suffered as a result of the tragedy, who approaches it, at State expense so that the healing process started by it becomes meaningful. In view of the statement of the learned Solicitor General no further directions in that behalf are as such necessary to be issued by the Commission.136

The Commission thus left the development of reparations to the goodwill of Punjab, which has not only consistently denied the rights violations and refused to accept responsibility throughout the proceedings, but has also failed to take any reparative steps to heal the wounds of the families.

We provide some examples below where the NHRC’s interpretation of its mandate has left out individuals who suffered violations of the rights to life and liberty. By limiting its mandate to these 2,097 cremations, the NHRC has excluded:

Victims of “disappearances” by Indian security forces, where the families have no knowledge of the victim’s ultimate fate; Victims of unlawful killings whose bodies were dumped in bodies of water, dismembered and dispersed, or disposed of through other methods; Victims of unlawful killings whom the Punjab police illegally cremated in other districts of Punjab; Victims of unlawful killings whom the Punjab police illegally cremated prior to 1984 and after 1994 in the three crematoria at issue in Amritsar district; Victims of unlawful killings whom the Punjab police illegally cremated, but who were not included in the CBI’s list of 2097 cremations, including those cremated at other cremation grounds in Amritsar district; and Victims of other human rights violations, such as custodial torture and illegal detention.

The case of Jugraj Singh, son of Mohinder Singh

This case illustrates the exclusion of cases of individuals cremated in Amritsar after 1994, and therefore outside the NHRC’s limited mandate. Jugraj Singh was abducted from Ropar district, but killed and cremated in Amritsar district in January 1995. (This case is discussed in detail later in this chapter to illustrate the failure of the courts in addressing extrajudicial executions.)

On January 14, 1995, 27-year-old Jugraj Singh, a taxi driver, was driving his Maruti van towards the market of Phase III B-2 Mohali, Ropar, to get his vehicle repaired. As he proceeded, individuals in civilian clothes signaled him to stop. An eyewitness later told Mohinder Singh, Jugraj Singh’s father, that the individuals who stopped the van had been waiting for a while and had come to the market in a Maruti car with registration No. PCO-42. When Jugraj stopped his vehicle, these individuals forcibly entered his van and had him drive away.

The next day, Mohinder Singh went to the police station to register a complaint, stating that people had witnessed his son’s abduction by the police. The day after, he visited the market and spoke to the owner of the shop next to the mechanic’s shop. This man confirmed that he had seen Jugraj in a van with police, and that the police had also abducted Sukhdev Singh from his shop.137

The police reported that Jugraj Singh was killed on January 15, 1995, in Amritsar in what they claimed was an armed encounter. Considering that eyewitnesses saw Jugraj Singh being abducted by the police, his father Mohinder Singh believes he was killed in a faked encounter.138 According to a CBI inquiry, officials of the Municipal Corporation in Amritsar cremated his body.139 Because his son was killed one month after the time boundary fixed by the Supreme Court and the NHRC, Jugraj Singh has been excluded from the Punjab mass cremations case.

The case of Charrat Singh and Rashpal Singh, sons of Gurbachan Singh

On November 17, 1988, Gurbachan Singh’s youngest son Rashpal Singh, about 15 or 16 years old, was traveling on a bus to visit his maternal family, when Punjab police stopped the bus and removed Rashpal and another youth. That same day, the newspapers reported that the police killed five persons in an alleged encounter. Gurbachan Singh learned that those five persons were cremated at Durgiana Mandir cremation ground in Amritsar—one of the cremation grounds investigated by the CBI. After speaking to employees there, Gurbachan Singh believes that his son was one of the individuals cremated because his son matched the physical description of a victim. His cremation, however, does not appear on the CBI list, and has thus been excluded from the Punjab mass cremations case by the NHRC’s limited mandate.

On June 18, 1989, between 4 and 5 p.m., approximately 100 security personnel from the Punjab police, Criminal Investigation Agency (CIA) Staff, and Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) raided Gurbachan Singh’s village Johal Raju Singh in Tarn Taran, Punjab. Gurbachan Singh told Ensaaf:

The security forces proceeded to my residence and then my fields, where my son Charrat Singh and I were working. The Punjab police grabbed Charrat Singh and me, brought us to the small tube-well by the village, and began to savagely beat my son with their rifle butts. …They drove away with me and my son, but dropped me off on the way, and that was the last time I saw him. The security forces took my son to CIA Staff, Tarn Taran. Many folks from the village accompanied me to CIA Staff, where we asked to see my son and requested his release, but the police refused.140

On June 24, 1989, the Punjabi daily Ajit reported that unidentified persons had been killed in an encounter. A few days later, Gurbachan Singh and his family went to Police Station Tarn Taran (Sadar) to verify the news of the killing:

At the police station, we spoke with the clerk, who showed us a pile of clothes, and asked if we recognized any of them. Among the articles of clothing, we recognized the parna (small turban) worn by Charrat Singh on the day the security forces abducted him. We were allowed to view Charrat Singh’s parna, but the clerk did not allow us to take it with us.141

Gurbachan Singh did not receive the bodies of either of his “disappeared” sons, nor was he informed of their cremations, but he believes them both to have been killed by the Punjab police.

In response to the November 2006 notice issued by the Amritsar Commission of Inquiry, Gurbachan Singh submitted claims regarding both his sons. His claim for Rashpal Singh was never considered because Rashpal Singh’s cremation did not appear on the CBI list.

Justice Bhalla eventually allowed Gurbachan Singh to submit information on Charrat Singh’s death because Charrat Singh’s cremation matched an unidentified cremation on the CBI list of 814 remaining unidentified cremations. The Punjab police, however, rejected the identification of Charrat Singh.142 Justice Bhalla confirmed the police’s rejection of the identification, stating that Gurbachan Singh’s affidavit was not sufficient because Gurbachan Singh himself did not see Charrat Singh’s dead body. Justice Bhalla did not mention Gurbachan Singh’s identification of Charrat Singh’s belongings in police custody .143

The unlawful killings of Gurbachan Singh’s two sons highlight the disparate remedies available because of arbitrary distinctions resulting from the NHRC’s limited mandate and failure to investigate cases.

The case of Mehal Singh and Gurmail Singh, sons of Dara Singh

Dara Singh lost two of his four sons to extrajudicial killings: his youngest son Mehal Singh, aged 16, and his oldest son Gurmail Singh, aged 37.144 The NHRC did not acknowledge Dara Singh’s submission regarding Gurmail Singh because its limited mandate excluded cremations outside of Amritsar. In August 2000, the State of Punjab found 18 cases eligible for compensation with no admission of liability or wrongdoing, including that of Mehal Singh. Dara Singh rejected this compensation. Despite the fact that the individuals in these cases had been fully identified, the case of his son later reappeared on the unidentified list.145 The Punjab police now denies that Mehal Singh’s body was ever identified.146 The Bhalla Commission has also rejected the identification of Mehal Singh’s remains, because his father did not see his dead body and the doctor who conducted the post mortem and confirmed his son’s identity did not depose before the Commission.147

Dara Singh told Ensaaf:

My youngest son Mehal Singh was an apprentice at a tractor repair workshop in Tarn Taran. On the night of June 17 to 18, 1989, [names of police officers withheld] from Tarn Taran (Sadar) police station led a heavy police force …including the Punjab police and the CRPF, in raiding my house. It was after midnight when they came.

The security forces began beating me and my sons. They tied our hands behind our backs and lined us up facing a wall in the courtyard and threatened to execute us right then. The security forces thoroughly searched the house, and stole several valuable items, but did not recover anything incriminating….148

They then detained us at the police station for two hours and continued beating us, especially Mehal Singh. [Names of two police officers withheld] started torturing Mehal Singh. Around 5 a.m., they transferred all of us to the CIA Staff Interrogation Centre in Tarn Taran. There again, they segregated Mehal Singh and tortured him under the supervision of [name of third police officer withheld]. The rest of us were seated on the floor outside of the cell where they were torturing him, and we could hear his shrieks from the torture. Later that day, they transferred all of us, except Mehal Singh, to the Tarn Taran Sadar police station. They detained us for two days and interrogated us about weapons and threatened to kill us.149

The police officers released all of them, except Mehal Singh, on June 19, 1989. Dara Singh said he then immediately collected many respectable people from his area and went to CIA Staff Tarn Taran to inquire about Mehal Singh. Gurbachan Singh of village Johal Raju Singh, whose testimony is cited above, joined the delegation since his son Charrat Singh had also been abducted by the Tarn Taran police. But the station house officer denied custody of Mehal Singh and Charrat Singh. Dara Singh told Ensaaf:

Every day thereafter, I waited by the butcher shop [referring to CIA Staff Tarn Taran] to see if they would release my son. On June 24, by chance, I was by the entrance to the civil hospital where they conduct post mortems. There, I saw a tractor-trolley parked, and I guessed that there were bodies in the trolley. I went towards the trolley and attempted to climb in to see if my son was inside, but a policeman, who was sitting in the passenger’s seat, warned me not to get in. The trolley took off a few moments later. I followed the trolley, [walking] to the cremation ground by myself, which took about an hour.

At the cremation ground, I met one of the workers. He said that the police had just dropped off two bodies for cremation, and pointed to where they were being cremated. There were several other bodies being cremated in a line. I went to the cremations he indicated.

I wasn’t certain that the bodies were Mehal Singh and Charrat Singh, so I continued to try to find out what happened to them.150

About 8 to 10 days later, Dara Singh and a colleague who knew the doctor who performed post mortems at the civil hospital, went and spoke to the doctor. The doctor told him that he had conducted post mortems on two youth who fit the description of Mehal Singh and Gurbachan Singh’s son Charrat Singh. The doctor further described the clothes the boys were wearing. Dara Singh told Ensaaf:

We hired an attorney and obtained an order from a judge in Tarn Taran directing the police to show us the clothes in their possession. We took the order to Tarn Taran (Sadar) Police Station and spoke with the SHO. He said that we should perform our religious rites for the dead for Mehal Singh and Charrat Singh. We took this to mean that they were dead.151

The police continued to harass Dara Singh and his family, detaining them two to three more times. They wanted the family to produce Gurmail Singh, Dara Singh’s eldest son:

In the second week of June 1990, Gurmail Singh joined a Kar Sewa group renovating a gurdwara at village Gharam in Patiala district on the Punjab-Haryana border. Ten or 12 days later, a group of police officers from Ambala district in Haryana came to our village and made inquiries about the identity of Gurmail Singh, who, according to a newspaper report, had been killed in an encounter along with four other militants. The newspaper report did not mention my son’s name, but called him an unidentified militant. However, I recognized my son’s photograph that was published in the article. …Fearing further reprisals against my remaining sons, I didn’t pursue the matter. The families of the other encounter victims told us that the youth had been cremated in Ambala, the place of the encounter.152

In 1999, Dara Singh responded to the NHRC’s notice for claims regarding mass cremations. He submitted claims on behalf of Mehal Singh and Gurmail Singh. The NHRC decided that the family was eligible to receive compensation for the wrongful cremation of Mehal Singh, but Dara Singh rejected the compensation:153

Money is not justice. The police murdered both of my sons, and they won’t even admit that they did something wrong. They call my sons terrorists! The police are the terrorists.…. The government should also give us copies of their records relating to the murder of my sons, so we can figure out what really happened.154

In its October 9, 2006 order, which effectively closed all of the major issues dealing with the matter of police abductions leading to “disappearances” and secret cremations in Punjab, the NHRC appointed a commissioner of inquiry in Amritsar, retired High Court Judge K.S. Bhalla, to identify as many as possible of the remaining 814 cremation victims from the CBI list within eight months. The number of unidentified cremations was subsequently revised to 800.155

After its appointment, the Bhalla Commission and NHRC held ex parte meetings, excluding the petitioner CIIP.156 As a result, the NHRC issued an order on October 30, 2006, that limited participation in the Bhalla Commission proceedings to those families who were among the 1,857 families who had submitted claims in response to NHRC public notices issued in 1999 and 2004. The NHRC also restricted all 1,857 claimants from participating in the proceedings by requiring the claimants to resubmit their claims in response to a public notice issued in November 2006.157 The end result was that only 70 of 1,857 claimants were eligible to participate in the Bhalla Commission proceedings.158 In its October 30, 2006 order, the NHRC did not provide any rationale or legal justification for narrowing participation in the Bhalla Commission through such a procedure.

The NHRC limited Justice Bhalla’s mandate to identifying the remaining illegal cremations, but placed no further restrictions. However, Justice Bhalla demonstrated little interest in the underlying facts. In his February 3, 2007 order, he explicitly stated that human rights violations by the police did not fall within his scope of inquiry.159Further, at the April 10, 2007 hearing, Justice Bhalla stated:

Naturally, if the police had known the identity of the individuals, they would have turned over their bodies to the families. What interest would they have in keeping the bodies?160

This comment reflected Justice Bhalla’s dismissal of the contention that the police purposely covered up the identities of the individuals and destroyed their bodies in order to eliminate significant forensic evidence of torture and custodial death.

Justice Bhalla continued the NHRC practice of relying on the Punjab police for identifications or confirmations of victims of illegal cremations, instead of developing an independent methodology or conducting his own investigations.

While CIIP and other petitioners submitted identification information to Justice Bhalla, he waited for confirmation from the Punjab police. If the Punjab police rejected the identification, Justice Bhalla placed insurmountable evidentiary burdens on the petitioners, requiring them to produce evidence of the dead body or cremation.

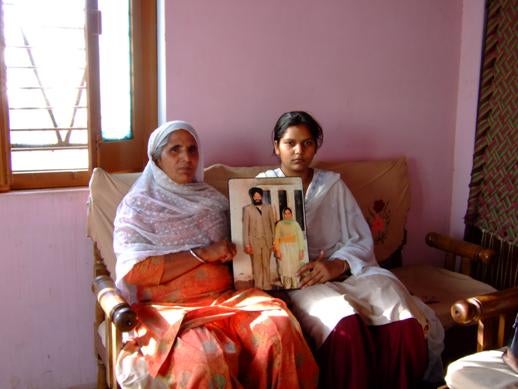

These women, whose family members were “disappeared” or extrajudicially executed by the Punjab police, regularly attended hearings of the Bhalla Commission in Amritsar but did not receive an opportunity to testify because they were excluded by the Commission’s arbitrary procedures.

© 2007 Ensaaf

At the initial hearings, through written and oral argument, the CIIP urged the Commission to adopt a rigorous methodology to resolve the unidentified cremations, and require the State to produce police records, post mortem reports, habeas corpus petitions, and news reports on abductions, “disappearances” and encounters. The CIIP also urged the Commission to solicit claims from throughout Punjab and allow all prior and new claimants to participate in the proceedings. The Bhalla Commission rejected these arguments at the February 3, 2007 hearing.161

Justice Bhalla further restricted the access of relatives to the commission, stating that victim families could not submit claims directly to the Commission, although they could provide information for the limited purpose of identification through CIIP or other petitioners. He did not explain how families excluded by the October 2006 NHRC order and November 2006 notice would know that they had this limited option. It was clear, however, that Justice Bhalla would not allow these families to testify.

The NHRC and Bhalla Commissions never acknowledged the possibility that the remaining 800 unidentified bodies could not be identified from the pool of 1,857 prior claims, and that a more inclusive process of participation was required if the Commissions were serious about establishing the identities of all 800 victims. At least 10 percent of the victims previously identified by the NHRC as having been secretly cremated in Amritsar lived outside of Amritsar district.162 The CIIP repeatedly suggested issuing a public notice throughout Punjab, inviting all victim families who believed their relatives may have been cremated in Amritsar to submit claims; these suggestions were rejected by the Bhalla Commission.163

The Bhalla Commission held its last hearing on June 29, 2007, and presumably submitted its final report to the NHRC. This report, according to the NHRC’s October 30, 2006 order, was due on June 30, 2007. The petitioners have not yet received a copy of the report. The NHRC initially scheduled a hearing for August 2007, but has postponed the hearing three times.164

B. CBI failure to investigate extrajudicial killings

The Supreme Court had entrusted the CBI with investigations into the culpability of police officials in the secret cremations case.165 The CBI was ordered to submit quarterly confidential progress reports.166Over 10 years later, the petitioners have no information regarding whether there have been any prosecutions.

In a July 1996 order, the Supreme Court ordered the CBI to register three cases—those which had specifically been mentioned in Jaswant Singh Khalra’s press release regarding his investigations: Pargat Singh “Bullet,” Piyara Singh, and Baghel Singh.167 The Punjab police responded that Baghel Singh was run over by a truck while being brought to Amritsar,168 Piyara Singh was killed by an ambush while being taken for recovery of weapons,169 and Pargat Singh was killed in an encounter.170

The case of two Pargat Singhs

The case of Pargat Singh “Bullet” illustrates the Punjab police’s practice of falsely identifying cremation victims, and the CBI’s collusion in that practice.

At the time of the July 1996 Supreme Court order mandating a CBI investigation into Pargat Singh’s death, the only information available was the date and place of cremation, the police station allegedly involved in the abduction and illegal cremation, and that Pargat Singh had allegedly been undergoing treatment at the Guru Nanak Dev hospital in Amritsar.171

But Pargat Singh has never properly been identified. One man, retired army officer Baldev Singh, claims he saw his son, named Pargat Singh, being cremated. However, the CBI and police have refused to respond to his pleas, and instead insist that the Pargat Singh that was cremated by Punjab police was the son of another man we can only identify as G. Singh at his son’s request. Both Pargat Singhs were nicknamed “Bullet.”

In the first year of the legal proceedings, Baldev Singh submitted an affidavit through CIIP regarding the extrajudicial execution and illegal cremation of his son, known as “Bullet,” after his detention by the Punjab police on September 19, 1992, from a movie theatre in Amritsar.172

The police started questioning Pargat Singh and his family in October 1988 and tortured Pargat Singh during six days of illegal detention. Later, when the police could not find Pargat Singh because he had gone underground, they illegally detained and tortured Pargat Singh’s father and older brother. Baldev Singh told Ensaaf:

[T]hey arrested me over 200 times during a period of two-and-a-half years and tortured me on many of those occasions. They would always ask me to turn over my son. But how could I? He was underground and never came home. During those days, the entire family stayed away from home. If I wasn’t home when the police came, they would take my wife and son and wouldn’t release them until I turned myself in.173

On September 20, 1992, Baldev Singh learned that Pargat Singh “Bullet” had been taken into police detention. He learned of the detention from his sister who met Pargat Singh in custody when she visited her son who had also been detained. (Her son was later released).

Baldev Singh immediately went to the police station to look for his son but was refused. He then began desperately to try to locate his son. One deputy superintendent of police (DSP) confirmed to a close police contact of Baldev Singh’s that Pargat Singh was in police detention, but refused to release him. Baldev Singh also learned that the police took Pargat Singh to B.R. Model School, an unofficial interrogation center, and tortured him.

Five days later, Baldev Singh asked another person who knew the district’s senior superintendent of police (SSP) to inquire after Pargat Singh. Baldev Singh said,

The SSP told him that Pargat Singh had been taken to the hospital for treatment. After that, I have no idea where they detained Pargat Singh or what they did to him, until I learned about his encounter.174

On the morning of November 5, Baldev Singh’s friend met with the SSP to ask about Pargat Singh. This time Baldev Singh heard that his son had been killed:

The SSP told him that yesterday they had killed Pargat Singh in an encounter and would cremate his body that day at Durgiana Mandir. The SSP further said that they would not turn over his body.175

The same day, Baldev Singh also read in the paper that Pargat Singh “Bullet” had been killed in an encounter. A former member of parliament (MP) from Amritsar, who had been helping the family locate Pargat Singh, called the SSP of Tarn Taran and asked for the body for cremation. The SSP told the MP they could attend the cremation at Durgiana Mandir cremation ground at 4 p.m. The MP advised Baldev Singh to go to the cremation ground immediately, since he could not trust the police. Baldev Singh recounted in his affidavit how he witnessed the cremation of his son:

I went to the cremation ground at Durgiana temple to ask whether the police had already cremated him [Pargat Singh]. He had not been. Then I went to the General Hospital [Guru Nanak Dev hospital] where his post mortem had been conducted. There I talked to an employee who had helped with the post mortem. He gave a detailed description of the body confirming that the person murdered in the faked encounter was indeed my son Pragat [sic]. He also told me that the police had taken the body away for the cremation. I rushed back to the cremation ground. The pyre had already been lit.176

Baldev Singh told Ensaaf:

Pargat Singh’s body had just started to burn from the head. His body was on a stack of firewood, and then more wood was stacked on top of his body. We rushed to the pyre and removed the wood on top. His body was wrapped in a blanket. We ripped it open with our fingers. The blanket was rotten so it came apart easily. I immediately recognized my son’s body. We saw bullet wounds on the left side of his body with exit wounds on the right. Once I was satisfied, we placed the wood back on top and allowed the pyre to burn.177

The police cremated Pargat Singh “Bullet,” son of Baldev Singh, on November 5, 1992; the next day the family collected his ashes.

The CBI visited Baldev Singh in the winter of 1996. He told them he wanted justice, but never heard from them again. Baldev Singh later learned that the CBI had refused to list his son as one of those identified as having been cremated by the Punjab police. He was instead identified as another Pargat Singh, a resident of M— village and son of G. Singh. Baldev Singh said he tried to convince the police that he had witnessed his son’s cremation, but to no avail. He was instead asked to produce his son.

In November 2006, an inspector from B-Division summoned me to the police station. He asked me to identify my son. I told him that my son was Pargat Singh and that he had been killed in a fake encounter. He started berating me saying that he didn’t believe me. He said that Pargat Singh belonged to a family from village M—. He told me that it was impossible for there to be two Pargat Singh’s from two different families, both killed in the same encounter, yet only one body. He then demanded that I turn over my son. I told him that he could say whatever he liked, but I saw my son’s body with my own eyes. He continued shouting at me, saying there couldn’t be two Pargat Singhs. I told him that was for him to explain, not me, but I saw him with my own eyes.

I returned about one week later to determine if they would acknowledge my son. The inspector said that he wouldn’t recognize my claim. He would recognize the family from M— village. According to his documentation, they were Pargat Singh’s family so he would decide in their favor. There was nothing else I could say, so I left.

The government should tell me what really happened. They should acknowledge my son’s death. I saw him with my own eyes. How can they tell me that it wasn’t my son?…They made my family suffer. Nobody was willing to marry my daughter. I’m not hungry for money, I’m hungry for justice.178

The CBI continues to identify the Pargat Singh who was cremated on November 5, 1992, as the son of G. Singh, not Baldev Singh.

The Pargat Singh that the CBI list acknowledges was the son of G.Singh and nicknamed “Mini Bullet.” Pargat Singh’s brothers told Ensaaf that he was a militant with the Khalistan Commando Force (KCF). The police regularly harassed his family. K. Singh, Pargat Singh’s brother, recounted to Ensaaf:

All in all, over the years, I was abducted and tortured 15 to 17 times. Chabal, Bhikiwind, Khalra, Harike were the main police stations involved. My father was abducted five to six times. In 1992, the police detained me continuously for seven months at various police stations, and beat me. When they transferred me between police stations, they would blindfold me, so I didn’t know where I was. I was released five to six days after they killed my brother Pargat Singh.179

According to the Punjab police, Pargat Singh of M—village was cremated on November 5, 1992, the same day that Baldev Singh witnessed the cremation of his son Pargat Singh. Only one Pargat Singh’s cremation is recorded on that day in the cremation ground records.180 The family of G.Singh read about the cremation at Durgiana Mandir cremation ground in the Ajit newspaper and went to collect the ashes; the cremation ground workers did not give the ashes to them.

As discussed above, in July 1996, the Supreme Court ordered the CBI to investigate the killing of Pargat Singh “Bullet.” One of his brothers, K. Singh, described the extent of investigation:

Many years later, the CBI visited our house to ask us about Pargat Singh’s death. They came a total of four times. The first two times the CBI came from Patiala. The first two times we were afraid to talk to the CBI and told them that we didn’t know anything. Then we spoke with Mrs. Khalra [Jaswant Singh Khalra’s widow] and she said that it was okay to speak with them—that they were investigating our case.

The CBI from Amritsar then visited us twice in the same year. We told them about our history of persecution and whatever we knew about Pargat Singh’s death. The CBI actually had more information than we did. They told us that the Raja Sansi police had faked the encounter of Pargat Singh. They said that some woman had admitted Pargat Singh to the hospital ten days earlier because of pain in his appendix. Then, on November 4, 1992, Raja Sansi police abducted Pargat Singh from the hospital and then cremated him at Durgiana Mandir the next day. They further said that Sub-Inspector[Name withheld]of Raja Sansi Police was the main accused.181

K. Singh described the lack of court proceedings:

In 2001, we received a letter from the CBI Patiala telling us to come to court to give testimony. About ten days later, I went to Patiala to the address indicated on the letter. I went to some government office. There, someone told me to go to an attorney’s office. I went to that attorney’s office and met a clerk. The clerk told me to return in about a month. I went back a month later to the clerk. The clerk told me that if we wanted to fight our case, we would have to give him 20,000 rupees—5,000 for him and 15,000 for the attorney. I told him that we had no ability to pay that amount and left. After that, the CBI never contacted us again. We have no idea if the CBI ever prosecuted anybody for Pargat Singh’s murder.182

Baldev Singh continues to dispute which Pargat Singh was killed and cremated on November 5, 1992. The CBI acknowledges the cremation of a Pargat Singh, but still insists he was the son of G. Singh.

The killing of Piyara Singh

In July 1996, the Supreme Court ordered the CBI to register a case regarding the killing of Piyara Singh.183 Piyara Singh’s son Balraj Singh, however, told Ensaaf that the CBI approached the family only twice during its investigation and the family has no knowledge of any criminal prosecution pursued in response to the Supreme Court order.

Balraj Singh said that a police team arrested his father in 1987 and tortured him for five to six days. In 1989, a police force arrested his father at his home and brutally tortured him, using a heavy roller, suspending him, tearing his legs, pulling his nails out of his feet, and impaling his legs with sharp, heated iron rods. In 1990, out of fear of the police, Piyara Singh moved to Uttar Pradesh to live with his sister.

In 1992, Balraj Singh was visiting his father in Uttar Pradesh when the police came to the village disguised as a group of doctors:

They approached my father’s neighbors, saying they wanted the presence of a prominent person to inaugurate a hospital. The neighbors mentioned my father, but said that he wasn’t home. The police said that they would wait nearby and asked the neighbors to signal them when my father returned.

When my father returned home and entered the house, about 10 to 12 policemen rushed in after him and tackled me and my father. They tied our arms behind our backs and took us away on a mini truck.184

The police took Balraj Singh and his father Piyara Singh to the B.R. Model School Interrogation Center, and placed them about three cells apart:

They started torturing my father. I could hear his screams into the morning. That night, around 9 p.m., they came for me and tortured me for about an hour. But they tortured my father continuously for three days. I could hear his screams the entire time. After the third day, I could no longer hear him, so I assumed they had tortured him to death.185

After his release over two weeks later, Balraj Singh learned that the police reported that his father had been killed in an encounter. He further learned from his family that his grandfather and Jaswant Singh Khalra had gone to Durgiana Mandir cremation ground and spoken with a cremation ground worker. Khalra knew Piyara Singh because they were both bank directors.

According to Balraj Singh, the family did not hear from the CBI again after 1996.

C. The murder of Jaswant Singh Khalra: Intimidation of witnesses and superior responsibility

In the early 1990s, human rights defender Jaswant Singh Khalra joined the Human Rights Wing of the political party Akali Dal.186 In 1994, while investigating the disappearance of a personal friend, Khalra discovered that the police had secretly cremated his body at Durgiana Mandir cremation ground in Amritsar district. Khalra launched a wider investigation into secret cremations.187

In January 1995, Jaswant Singh Khalra and his colleague Jaspal Singh Dhillon released a report on mass illegal cremations using government records. KPS Gill, the director general of police (DGP) in Punjab, responded to their evidence by accusing Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) of trying to destroy peace in Punjab and alleging that most of the “disappeared” persons were living abroad.188 Khalra discussed DGP Gill’s statements in April 1995:

KPS Gill said in a press conference in Amritsar, ‘These Human Rights Wing folks—they’re not doing anything on human rights. They have one motive, to prop up their agenda, so there is no peace in Punjab. They are ISI agents, and they are hatching a conspiracy to discourage the police machinery and re-incite militancy.’ KPS Gill went to the extent of saying, ‘I’ll tell you where those kids are.’ He said, ‘These kids are in Europe, in Canada, and in America, where they are earning their daily wages. And these human rights organizations are telling us that thousands of kids have disappeared.’ This was a challenge to us. This was a challenge to that truth which we sought to bring forward.189

Khalra challenged DGP Gill to an open debate on the evidence.190 In February 1995, at a press conference, Khalra publicly disclosed the death threats made to him because of his human rights work.191 He also discussed these death threats with various other individuals, especially threats made by the Tarn Taran police under the command of Senior Superintendent of Police (SSP) Ajit S. Sandhu, who had been transferred back to Tarn Taran district after Khalra released his investigative report.192 Sandhu allegedly threatened Khalra that he, too, would become an unidentified dead body.193 In March, the police tried to discredit Khalra by alleging that he had links with a militant group.194 Khalra continued to expose police officials, speaking throughout Punjab and North America on the issue.

On the morning of September 6, 1995, the Punjab police abducted Jaswant Singh Khalra. Rajiv Singh, a reporter who was present at the Khalra residence, witnessed the abduction and identified the police officers involved. Rajiv Singh saw three uniformed policemen and one policeman in civilian clothes exit a Maruti van. According to Rajiv Singh, two of the police officers, Station House Officer (SHO) Satnam Singh of Police Station Chabal and Head Constable (HC) Prithipal Singh of Police Post Manochahal, carried carbines, and Deputy Superintendent of Police (DSP) Jaspal Singh, also uniformed, had a walkie-talkie set. DSP Ashok Kumar sat in the front seat of the Maruti gypsy, or jeep, on the left side of the driver’s seat. Surinderpal Singh, SHO of Police Station Sarhali, sat in the front seat as well. Rajiv Singh further observed five to six uniformed policemen sitting in the back of the Maruti gypsy; one of them was Jasbir Singh, in-charge of Police Post Manochahal, another was Assistant Sub-Inspector (ASI) Amarjit Singh, and a third was Avtar Singh Sona, son of SSP Sandhu’s nephew Jagbir S. Sandhu.195

Rajiv Singh heard DSP Jaspal Singh tell Khalra that SSP Sandhu wanted to meet him. Khalra was forcibly placed between DSP Jaspal Singh and HC Prithipal Singh in the van. Rajiv Singh then heard DSP Jaspal Singh make a call on the walkie-talkie and state that the work was completed.196 Khalra was then taken away in the Maruti van, followed by the Maruti gypsy. Kirpal Singh Randhawa, a resident of the same neighborhood, also claimed to have seen the vehicles.197

After the abduction, Rajiv Singh called Paramjit Kaur, Khalra’s wife, and informed her of the abduction. She immediately came home from work and, accompanied by Rajiv Singh, went to Islamabad Police Station to make further inquiries. She then informed her family and husband’s colleagues, and also sent telegrams to the chief minister of Punjab, director general of police, chief justice of India, and chief justice of the Punjab and Haryana High Court, among others.198 A few days later, Paramjit Kaur filed a habeas petition in the Supreme Court. Khalra’s abduction by the police was never recorded in police records,199 and the police maintained that there was no criminal case against him and thus no reason to arrest him.200

As a court subsequently confirmed, the Punjab police illegally detained and tortured Khalra for almost two months before killing him in late October 1995 and, discarding his body in the Harike canal in Amritsar, Punjab.201 Several days prior to his murder, the police allegedly took Khalra to SSP Sandhu’s residence, where KPS Gill allegedly joined them and interrogated Khalra for half an hour. On the ride back to the police station, SHO Satnam Singh told Khalra that if he had listened to DGP Gill’s advice, he would have saved his life.202

In November 1995, the Supreme Court directed the CBI to investigate the kidnapping of Jaswant Singh Khalra.203 The CBI filed a charge sheet against nine police officers from Tarn Taran district on October 30, 1996, but did not arrest any of the accused.204 Initially, the CBI only charged the police officers with kidnapping and illegal confinement, and not torture or murder.205 After Paramjit Kaur Khalra’s attorney intervened in 1997,206 the court revised the charges to include murder charges against three of the officials.207

On November 18, 2005, over ten years after Paramjit Kaur Khalra filed a habeas corpus petition regarding her husband’s abduction, Additional Sessions Judge Bhupinder Singh convicted and sentenced six Punjab police officers for their roles in the abduction and murder of Khalra.208 Two other police officers—SSP Sandhu and DSP Ashok Kumar—died during the course of the trial, and one other police officer was not prosecuted and discharged.209 The convicted police officers have appealed the convictions.210 Paramjit Kaur Khalra has appealed the leniency of the sentences, arguing that all who gave orders or otherwise participated in the murder should receive life sentences.211 The CBI has not filed any appeal.212

While the convictions of lower-level officers more than a decade after the murder represent an exception to the impunity otherwise enjoyed by the security forces for serious abuses committed during the counterinsurgency, even in this case justice has not been done. The truth has not been established, the most responsible senior police officials have not been charged, and the proceedings that have taken place have been marred by inordinate delays and egregious intimidation and harassment of witnesses.

There is even evidence that some of the officers convicted in 2006 are receiving special treatment. Individuals have informed Khalra’s widow that they have seen some of the convicted police officers out during weekends at bars, clubs and hotels, suggesting that they are periodically released from jail.213 Mrs. Khalra’s attorney Rajvinder S. Bains informed Ensaaf that DSP Jaspal Singh has stayed at home in Hoshiarpur when he was supposedly transferred to a local Hoshiarpur jail for cases proceeding against him in a local court.214

Prior to the conviction, moreover, in part due to the slowness of the proceedings and the CBI’s failure to make arrests, the accused repeatedly intimidated and threatened witnesses.

Police have retaliated against activists by implicating five of the key witnesses—Khalra’s wife Paramjit Kaur, as well as Kulwant Singh, Kikar Singh, Rajiv Singh, and Kirpal Singh Randhawa—in false criminal cases, ranging from bribery, rape, and robbery, to establishing a terrorist organization.215 The police arrested Rajiv Singh, the witness to Khalra’s abduction, at least twice to prevent his appearing in court to testify, and implicated him in a total of four cases, including the forming of a terrorist organization.216 The Punjab State Human Rights Commission investigated the terrorism charge and concluded that the police falsely implicated him.217 In 2004, prior to his testimony in the Khalra case, the police falsely implicated another eyewitness to the abduction, Kirpal Singh Randhawa, in a rape case, and accused both him and Rajiv Singh of allegedly threatening a witness in the rape case.218

The police further threatened Kulwant Singh, who saw and spoke to Khalra in custody on September 6, 1995, the day of Khalra’s abduction. 219 Kulwant Singh said that he was brought to the office of SSP Sandhu and questioned about Khalra by Sandhu, Station House Officer (SHO) Satnam Singh and Deputy Superintendent of Police (DSP) Jaspal Singh, three of the accused police officers.220 Kulwant Singh stated in his trial testimony that police officers threatened and asked him not to meet CBI officials in connection with the Khalra case.221

Police harassment appears to have been the reason Kikar Singh turned hostile during trial. Kikar Singh initially told the CBI that he saw Khalra in police custody at Police Station Kang on October 24, 1995, witnessed signs of torture on his body, and helped him eat:

At the time the hair of his [Khalra’s] beard and head had been plucked and he had blue marks of bruises under his eyes. His fingernails were also blue. He had bruises on his body. He could not eat his food with his hands. I fed him food with my own hands. After eating the food he was taken out by the sentry and Jaswant Singh Khalra was not even able to walk properly. I helped him by supporting him with a shoulder along with another person in civilian clothes.222

After giving his statement to the CBI, Kikar Singh repeatedly asked for protection.223 The protection was ineffectual. In his affidavit of August 29, 1996, Kikar Singh stated that SSP Sandhu and DSP Jaspal Singh were pressuring him to turn hostile by implicating his father and relatives in false cases and by conducting raids on his house.224 They forcibly took possession of his house and farm on August 25, 1996 in connivance with Kikar Singh’s security guard.225 After spending time in judicial custody, Kikar Singh turned hostile in Khalra’s case, denying any knowledge of Khalra, that they had been in illegal detention together, or that he had made two previous statements to the CBI regarding his knowledge of abuses against Khalra.226

Police officers appear to have intimidated a key witness into filing a false bribery case against Paramjit Kaur Khalra and her supporters. In March 1998, officers implicated in Khalra’s abduction visited Special Police Officer (SPO) Kuldip Singh, who had witnessed Khalra’s illegal detention, torture, and the disposal of his body. The police officers intimidated SPO Kuldip Singh into filing false bribery charges against Paramjit Kaur Khalra, threatening him and his wife with disappearance.227 The charges against Paramjit Kaur Khalra were quashed after SPO Kuldip Singh’s family denied his statement and human rights groups drew attention to the case.228 In November 2004, SPO Kuldip Singh expressed no confidence in Punjab police security and requested that a Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) vehicle replace the Punjab police vehicle that was bringing him to court.229

The CBI’s failure to charge Punjab Director General of Police (DGP) KPS Gill for his role in the abuses against Khalra highlights serious failures in the prosecuting authority of the CBI. To address the CBI’s failure to charge KPS Gill, Paramjit Kaur Khalra petitioned the court to allow her lawyers to intervene in the case. In a September 1997 order, the special judicial magistrate allowed her lawyers to argue, examine, and cross-examine witnesses, while acting under the directions of the public prosecutor.230

In 1997, after SSP Sandhu committed suicide, SPO Kuldip Singh approached the CBI with direct information on the abuses against Khalra. He said he had been too afraid to disclose this information while Sandhu was alive.231 SPO Kuldip Singh had served under SSP Sandhu since 1994, specifically as the bodyguard of SHO Satnam Singh, another accused in the Khalra case.232 In February 1995, when SSP Sandhu was transferred back to Tarn Taran after Khalra announced his discoveries, SPO Kuldip Singh and SHO Satnam Singh were also transferred with him.233 In his statement to the CBI, SPO Kuldip Singh described how he had been appointed to guard the room where Khalra was detained, and discussed the role of different officers, including the senior-most officer, DGP Gill, in the abuses against Khalra.234

The CBI appears to have actively worked to prevent the addition of Kuldip Singh as a witness in the trial. According to Kuldip Singh, SHO Satnam Singh told him on March 22, 1998, that the CBI officials who had recorded his statement had apologized to KPS Gill under pressure from the central government.235 On August 12, 1998, Paramjit Kaur filed an application in court for a direction to the CBI to present the supplementary charge sheet with the statement of Kuldip Singh.236 The CBI opposed this application, as did the accused; the court, however, ordered the CBI to present its supplementary report within a month.237 In its report, the CBI stated that they refused to add Kuldip Singh as a witness because his statement did not “inspire confidence” since it had been made two-and-a-half-years after Khalra’s abduction; they imputed his making the statement to his failure to secure a job in the Punjab police.238 According to the CBI, other police officers stated they had no knowledge of Khalra’s detention and KPS Gill also denied his role.239 Mrs. Khalra filed another application through her attorney in January 2000 arguing for Kuldip Singh to be added as a witness, which the CBI opposed.240 Only in October 2000, by order of the sessions judge, was Kuldip Singh added as a prosecution witness.241 The sessions judge found Kuldip Singh to be a material witness whose credibility could be assessed during cross-examination in trial.242

In February 2005, SPO Kuldip Singh gave his testimony in court and explained the sequence of events leading to Khalra’s custodial torture and murder, including the role of KPS Gill. He described how, in October 1995, he was handed the key of a room in Police Station Chabal by SHO Satnam Singh. SHO Satnam Singh told him that a man was being detained there and that he must serve him meals and keep his detention secret.243 SPO Kuldip Singh opened the door and saw Khalra there; his clothes were torn and there were bruises on his body.244 He described how he witnessed beatings of Khalra by the accused officers because Khalra had refused to stop his human rights work.245 One day, the police officers took Khalra to SSP Sandhu’s residence:

The condition of Sh. Jaswant Singh Khalra was not good as he had suffered beatings and was not able to walk and was brought to the car by me and Sh. Satnam Singh by holding him from arms. His wrist joints were swollen at that time and he was not able to even take his meals properly. He was also unable to go to answer the call of the nature. We had to support him for doing so.246

Thereafter, he said, KPS Gill visited SSP Sandhu’s house and interrogated Khalra for half an hour, and thus witnessed that Khalra could barely move from the torture he had experienced at the hands of Gill’s subordinate officers.247 SPO Kuldip Singh further testified that SHO Satnam Singh told Khalra to accept KPS Gill’s advice and save himself.248 SPO Kuldip Singh further described Khalra’s murder and the disposal of his dead body in Harike canal.249

SPO Kuldip Singh’s testimony established that DGP Gill defied Supreme Court orders regarding Khalra’s habeas petition. On September 6, 1995, Paramjit Kaur Khalra sent Gill a telegram informing him of her husband’s abduction.250 On September 11, 1995, five days after Punjab police abducted Khalra, the Supreme Court issued formal notice and service to DGP Gill of the habeas corpus petition filed by Khalra’s wife.251 Despite receiving this formal notice, DGP Gill failed to disclose Khalra’s whereabouts while Khalra was alive. On November 15, 1995, the Supreme Court ordered the CBI to inquire into Khalra’s “disappearance” because the police investigation had not yielded any results. The Court further directed DGP Gill to “render all assistance and help to the CBI.”252

According to the judge who passed the final order, Kuldip Singh “did respond properly to all the queries put forward to him by the defense counsel who could not shake his veracity despite detailed and lengthy cross-examination of this witness.”253 The judge found that the in-court statements made by Kuldip Singh were “fully consistent” with the statements he had given earlier to the CBI.254

Despite this detailed and consistent information, accepted now as findings of fact by a court of law, the CBI has failed to initiate an investigation of KPS Gill’s role in the abduction, torture, and murder of Khalra. After writing twice to the CBI requesting that it initiate an independent investigation and bring charges against former DGP Gill,255 with no reply,256 on September 6, 2006, Mrs. Khalra filed a petition in the High Court.257 Over a year later, this petition has yet to have a substantive hearing.258

One of the greatest obstacles to combating impunity is the failure to hold superior officials accountable. The international law doctrine of superior responsibility imposes liability on superiors for the unlawful acts of their subordinates, where the superior knew or had reason to know of the unlawful acts, and failed to take necessary and reasonable measures to prevent or punish those acts.259 Based on his acts and omissions, the Punjab Director General of Police, KPS Gill, could be liable under the doctrine for Khalra’s abduction, illegal detention, torture, and murder. The evidence suggests that Gill himself participated in crimes against Khalra, and failed to rescue or order Khalra’s release when he knew Khalra was being ill-treated.

A superior-subordinate relationship exists if the superior possesses “effective control” over a subordinate,260 which includes the ability to prevent or punish the commission of offenses.261 By his own admission, Gill exercised effective control over the Punjab police, and had intimate knowledge about the functioning of individual police stations.262 Gill wrote that he created an “active and accountable police leadership” and described how he worked to be a leader who led “from the front.”263 His de jure command, as evidenced by his own admissions and the high-level tasks he performed, creates a presumption of effective control.264 His de facto command over his subordinates also demonstrates his effective control, as evidenced by his ability to issue orders that were followed.265 Moreover, Gill was in a position to prevent and punish offenses with the power to initiate investigations and discipline subordinates.266 In September 1992, Gill himself said that his office was investigating more than 30 allegations of police wrongdoing and had fired more than fifty officers for misconduct.267 Furthermore, Gill thoroughly exercised his powers to reward and promote subordinates,268 and demanded regular communications and meetings with subordinates.269 All of these factors demonstrate that Gill had effective control over the subordinates who committed the crimes against Jaswant Singh Khalra.

KPS Gill appears to have had actual and constructive knowledge that his subordinates committed and/or were about to commit unlawful acts against Jaswant Singh Khalra because he witnessed Khalra’s illegal detention and tortured body.270 Further, his position in the chain of command, the timing of the abduction after Khalra exposed the mass cremations,271 the extensive use of police infrastructure and personnel to commit the crimes, also are strong evidence of his actual knowledge of the crimes. In this case, there were no fewer than nine police officers involved in the operation to abduct Khalra, including officers with the ranks of SSP, DSP, and inspector, who used police radios, weapons, and unmarked vehicles to abduct Khalra.272 Further, in May 1994, the Supreme Court heard a petition implicating the police abduction and disappearance of four Punjab human rights attorneys.273 At the time of Khalra’s abduction, one of the accused, SSP Sandhu, had at least 19 charges against him.274

KPS Gill had reason to know, or constructive knowledge, of his subordinates’ crimes against Khalra because of the number of complaints and court notices he received about Khalra’s abduction and threats to Khalra’s life, the information available in the public domain about the role of his subordinates in Khalra’s abduction, and general information on the violent history of his subordinates. Despite this actual and constructive knowledge that his subordinates had committed and were about to commit unlawful acts against Khalra, Gill failed to take necessary and reasonable measures to prevent his subordinates from committing unlawful acts against Khalra or to punish them afterwards. Gill could have prevented his subordinates’ crimes against Khalra with a simple release order and an order prohibiting further harm against Khalra. This measure was necessary because it was legally required by the Supreme Court and within his ability.

This case demonstrates the serious defects in the way the government has dealt with the abuses that accompanied the Punjab counterinsurgency operations. The lack of witness protection, the length of trials, duplicative investigations, the unwillingness to hold senior officials accountable, and government interference ensure that impunity for mass state crimes continues.

D. The killing of Jugraj Singh: Police intimidation and failure of due process

The lack of justice in India is like a cancer. It’s eating away at Indian society. But if you don’t tell people about it, then it will never get cured. You can’t be afraid to tell the truth.

-Mohinder Singh, father of Jugraj Singh

Unfortunately, the Khalra case is not an isolated example. The experience of Mohinder Singh in pursuing justice for the murder of his son Jugraj Singh also illustrates the role of the CBI in protecting the police, the intimidation of witnesses and petitioners, the failures of the judicial process, destruction of evidence by the police, and the lack of justice despite considerable efforts by affected families. It is further evidence that impunity continues to trump the rule of law in India.

On the morning of his abduction on January 14, 1995, Jugraj visited Mohinder Singh—they lived a few blocks apart in Mohali. Jugraj Singh told his father that he was going to the scooter market in Phase III B-2 to get his van fixed. When Mohinder Singh visited Jugraj Singh’s house around 8 or 9 p.m. that evening, his daughter-in-law told him that Jugraj had not returned. After speaking to neighbors, they learned that people at the market were saying that the police had arrested Jugraj. Mohinder Singh recounted:

A lot of people at the market knew Jugraj so it’s no surprise that they were talking about it. The day after the abduction the juice vendor, whose stall was in the market, told me that a blue Maruti car with license plate number PCO-42 parked at his stall around 7 a.m. and four plainclothes policemen stood around the car. When Jugraj passed the car in his van they jumped into the car and pulled out after him. The car overtook the van. Some of the men got out and signaled Jugraj. Jugraj stopped his van thinking they wanted a ride. They forced themselves into the van and took off towards Phase 8. Jugraj was a regular customer of the juice vendor’s and they knew each other well. A few days later, the juice vendor packed up and left.275

The next day, accompanied by two friends, Mohinder Singh went to the police station in Phase 8 to register a complaint:

I didn’t go to the police station immediately because it was late and I didn’t want to go alone.