<<previous | index | next>>

II. An Anatomy of Military Economic Activity

This chapter outlines the main features of the military’s economic activities and some of their negative consequences. It offers a typology of military economic ventures in Indonesia that places them in four broad categories: businesses owned or partly owned by the military, often via foundations and cooperatives; alliances with private businesses, many of which revolve around payments for security or other services; involvement in organized illicit business activity; and corruption. We explain the defining characteristics of each category and identify some sample ventures to show how the different kinds of economic activity play out in practice. Several of the examples illustrate that, in ways both large and small, military economic engagement helps undermine accountability, fuel conflict and criminality, and facilitate human rights abuses. This human rights analysis affords two key lessons: that the problem of military involvement in the economy is a serious one requiring immediate attention; and that any solution must be comprehensive in nature if it is to be effective.

Military-Owned Businesses

Companies owned in whole or in part by the Indonesian military span the full range of the economy, from agribusiness to manufacturing and from golf courses to banks. In September 2005 the TNI complied with a request from the Ministry of Defense for an inventory of its business interests.72 (Preparation of the inventory was a first step toward implementing the TNI law passed a year earlier that mandated the transfer of these businesses to government control.) The initial inventory identified 219 military entities (foundations, cooperatives, and foundation companies) engaged in business activity.73 As of March 2006, the TNI had provided information on 1,520 individual TNI business units.74 (See Table 1, below.) By April 2006, the Ministry of Defense had initiated a separate review process to examine whether its three foundations were engaged in business activity.75

Table 1: TNI Inventory of Military Businesses

|

Initial Inventory (September 2005) |

|

|

Foundations |

25 |

|

Companies under Foundations |

89 |

|

Cooperative Units Engaged in Business |

105 |

|

Revised Inventory (March 2006) |

|

|

Individual Business Units |

1520 |

Source: Ministry of Defense letter to Human Rights Watch, December 22, 2005; Maj. Gen. Suganda, then TNI spokesman,

“TNI commits to reform[,] upholds supremacy of law,” opinion-editorial, Jakarta Post, March 15, 2006.

The TNI and other authorities who have access to the inventory results have not publicly identified the individual business interests held by the military or provided information on their total value. Officials involved in the review of the military’s businesses declined to share a copy of the inventory with Human Rights Watch, to provide the names of the businesses listed on it, or to reveal the businesses’ total declared value.76 They said the data supplied by the TNI could not be considered final because it was “very rough” and included many entities that, in their view, did not constitute “real businesses.”77 According to these officials, the list incorporated many small-scale ventures, some with assets of negligible value, alongside other, much larger enterprises.78

|

Box 1: How Much are Military-Owned Businesses Worth? No reliable information is currently available about the value of the military’s business holdings. Most military-owned companies are privately held, rather than publicly listed, so their financial statements are not available for scrutiny.79 Up to mid-2005, when the TNI submitted an initial inventory of its businesses, even top military officials credibly maintained that they did not know the number, scope, value, or profits of the military’s business investments. In May 2005, for example, the air force chief said he lacked data about the number or profits of air force-owned companies.80 Ongoing government efforts to verify the financial condition of the companies listed in the TNI inventory should provide answers to such basic questions. In the meantime, public statements offer some indications. In mid-2005, unnamed officials told the Singapore-based Straits Times newspaper that the top twenty or so military companies in Indonesia had a total estimated annual income of $200 million.81 For the sake of comparison, perhaps the best available historical figure is one used by foreign finance officials. An “informal review” of a selection of eighty-eight military businesses in Indonesia found that they had a combined turnover of Rp. 2.9 trillion ($348 million) in 1998/1999.82 The Far Eastern Economic Review, referring to the same study, further revealed that annual revenue from the selected military businesses amounted to approximately Rp. 500 billion ($60 million).83 Contrasting this to the $200 million figure offered in mid-2005 (which covered a smaller number of companies), it appears that those military businesses that survived the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s were able to rebound significantly from that low point. (See below for additional data specifically for businesses held under military foundations.) |

Many of the military’s business holdings are little more than empty partnerships. The military’s stake in a company is typically a passive interest, also known as “golden shares” or “goodwill shares,” donated by the true investors with no expectation that the military will play an active role in the operation or management of the company.84 For example, in 2005, the commander of Kostrad (the army strategic reserve—see below) acknowledged publicly that over the years private investors had given Kostrad ownership stakes in various companies—and had done so for free.85 According to the Ministry of Defense, almost all TNI businesses have private-sector partners.86 Many are run as closely held companies, making it all the more difficult to obtain information on profits.87

Since the passage of the TNI law of 2004, the military has begun to liquidate some of its business holdings. The description below reflects the limited information that is publicly available about the extent of such restructuring. The military has argued that the TNI should be allowed to continue limited economic activity under its foundations and cooperatives. Thus, while some of the military’s business investments have been dropped, the presumption here is that the overall structure of military economic activity has not fundamentally changed.

Inevitably, formalized military businesses have led to a variety of independent economic ventures by military officers. These officers also have many opportunities to use their positions of power and influence to establish business ventures on their own or with private partners. High-ranking officers are in the most advantageous position to make business connections and form private-sector alliances. In addition, many mid-level officers are believed to run small businesses to earn extra income.88 In one example, a military intelligence officer reportedly owned an ebony business in Central Sulawesi.89 Commonly, an officer’s stake is assigned to his wife or another family member.90

It is worth noting that in many cases, though not all, the private business holdings of retired military personnel can be traced to the military as an institution.91 Many military retirees launch businesses or form relationships with private entrepreneurs while on active duty. For example, the former armed forces commander General (ret.) Wiranto has stated that he intends to build a resort in Sukabumi, on the West Java coast, on land he obtained, along with permission to build, in the 1990s.92 Local farmers, however, say they have farmed that land since the late 1960s and, under an agrarian reform law, claim to own it.93 Wiranto was a very senior official throughout the 1990s but was suspended from the post of security minister early in 2000 following allegations he presided over atrocities in East Timor.94

Foundations

Many important military business holdings have been established under the umbrella of tax-exempt foundations (yayasan). Military foundations were set up beginning in the 1960s to provide social services, such as housing and education, for the troops and their families. They soon expanded into businesses ventures as a way to generate revenue, ostensibly to pay for their welfare activities. The best known foundations have been those established by each of the service branches and special commands, as well as by TNI headquarters itself, but foundations also exist at other levels.95

Despite their nominally independent status, the military foundations were set up with funds donated by the government.96 As acknowledged by a senior Indonesian military official, Lt. Gen. Sjafrie Sjamsoeddin, for thirty years under Soeharto the military foundations benefited from monopoly control in many areas, priority for government licenses, and more generally the full backing and authority of an authoritarian government.97 As a result, the military’s foundations were economically prominent during the Soeharto years. They declined sharply in value as a result of the Asian financial crisis and poor management. Increased competition also was a factor. Military businesses still enjoyed certain privileges but after Soeharto’s fall they lost their dominance in many sectors.98 Some military-owned businesses were forced to close, while others underwent major changes.

Additional changes were required to comply with a 2001 law on foundations.99 That law specified that foundations could take part in business activities only indirectly through related entities whose activities were consistent with the foundation's designated social (or religious or humanitarian) purpose.100 This measure prompted military foundations to restructure their business interests and place them under holding companies. A separate provision in the law set a limit on the profit-making of foundations by capping investments at 25 percent of their assets.101

Foundations also continued to benefit from government resources. At least through 2001 government funds continued to flow to the foundations to help cover operational expenses, according to a government auditor who reviewed their accounts.102 Speaking that year, the auditor added that the military foundations “can and usually do take advantage of the resources and mandate of the founding department or agency” and were operated and managed by active military personnel: “In effect, these yayasans operate as quasi-governmental agencies.”103 The Indonesian government acknowledged this was true in a 2003 statement that referred to “military and other foundations receiving state funds or financing state activities.”104 In 2006, Lt. Gen. (ret.) Agus Widjojo, the former TNI chief of staff for territorial affairs and former deputy speaker of the People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR) from the armed forces faction, independently affirmed that, despite changes to staff the foundations with retired (rather than active-duty) personnel, they nevertheless retained strong ties to the military institution: “De facto, practically speaking, the foundations were established by the military command and the military command feels they own the foundation.”105

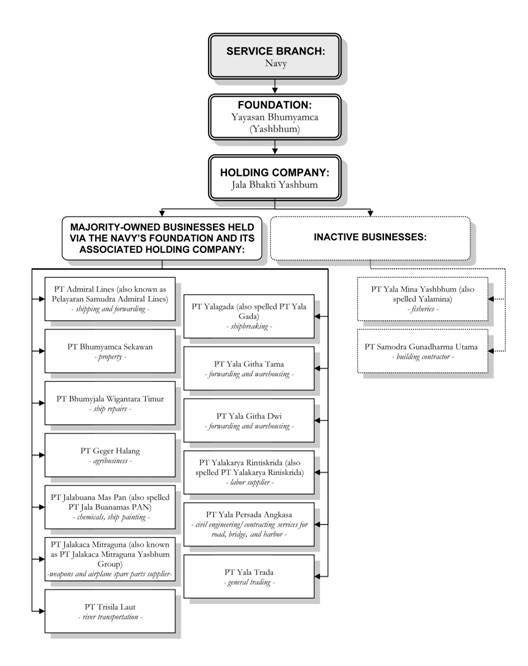

Each service branch has at least one foundation, and each foundation typically has at least one holding company that invests in individual businesses on the foundation’s behalf. The foundations may have sole or majority interest in the businesses but, as noted, often hold a minority stake though shares donated by private partners. (See “Illustrative Diagram of a Military Business,” below.)

Illustrative Diagram of a Military Business

Note: This example is provided here to demonstrate the ownership

structure of military businesses and does not purport to make a substantive

claim about the businesses listed. It is based on information provided by TNI

headquarters and supplemented by two people familiar with the navy’s businesses

because they reviewed them (in one case, as part of an internal review by the

navy and in the other independently).

(Information as of May 2006.)

|

Box 2: Military Foundations and their Assets The descriptions presented below reflect the information available to Human Rights Watch at the time of writing.106 Army: Yayasan Kartika Eka Paksi (YKEP). The largest military foundation, at least by reputation, it was established in 1972. Foundation holdings as of 2001 included eleven subsidiaries and twenty-two joint ventures. The disparate companies at that time fell into six broad categories: forestry/plantation, construction, property, manufacturing, services, and mining.107 Among its most visible holdings at one time was its part-ownership of the Sudirman Business District, a prime real estate development in Jakarta run by private partners that in 1999 was estimated to be worth $3 billion.108 Still suffering the effects of the financial crisis, YKEP suffered a net loss from its investments of approximately Rp. 8 billion ($880,000) per year in 2000 and 2001.109 The TNI chief declared in 2002 that YKEP generated a profit of no more than Rp. 50 billion ($5.5 million).110 The negative trend apparently continued: according to a former deputy army chief , Kiki Syahnakri, YKEP’s profits in 2005 showed a steady decline from previous years.111 As of that time, it was believed to have largely retained its earlier investments and to continue to own, among others, timber companies, hotels, property, and transport services.112 In 2006, the Ministry of Defense announced that one of the army’s most prominent businesses, PT International Timber Corporation Indonesia (ITCI), was in dire financial condition, as it was experiencing large losses and was unsure if it could pay its thirteen thousand employees.113 Kostrad (Army Strategic Reserve Command): Yayasan Kesejahteraan Sosial Dharma Putra (YKSDP Kostrad). This foundation was first set up as Yayasan Dharma Putra Kostrad (YDPK) in 1964, under Soeharto’s command. Information provided to Human Rights Watch in 2004 showed that YKSDP was believed to have an investment in thirteen companies, including in the automobile, plastics, and insurance industries.114 In April 2005, however, Kostrad commander Lt. Gen. Hadi Waluyo declared that his forces only retained an ownership stake in three companies: PT Mandala Airlines (100 percent), Darma Medika General Hospital (25 percent), and PT Darma Mandala (25 percent).115 He said they had divested themselves of all other business holdings because the businesses had fared poorly.116 Waluyo, in his capacity as the Kostrad chief, also served as a commissioner of Mandala Airlines.117 Potential buyers were reluctant to take over the company because of concerns that financial information was incomplete and presented the risk of hidden liabilities.118 In April 2006, Kostrad sold the foundering airline.119 Kopassus (the Army Special Forces Command): Yayasan Kesejahteraan Korps Baret Merah (Yakobame), formed in 1995.120 As of 2004, it was thought to have investments in the construction business.121 Air Force: Yayasan Adi Upaya (Yasau). Yasau owned ten companies in 2000.122 Its holdings in 2004 (eight companies) were in forestry, construction, property, airlines and related companies, and a pharmaceutical company.123 Several air force-owned businesses remained active as of early 2006, including PT Konstruksi Dirgantara (construction), PT Angkasa Pura (property), and PT Dirgantara Husada (pharmacy).124 Navy: Yayasan Bhumyamca (Yasbhum). Established in 1964, Yasbhum had thirty-two companies in 2000.125 The number of navy-owned companies had dwindled to six by late 2004, according to the then navy chief of staff, Adm. Bernard Kent Sondakh, who said these would be sold off to the private sector.126 Information provided by TNI headquarters, however, listed the navy as owning one holding company and fifteen individual businesses as of early 2006.127 (See “Illustrative Diagram of a Military Business,” above.) The TNI also identified two other navy foundations, Yayasan Nala and Yayasan Hangtuah, without indicating if they owned businesses.128 TNI headquarters: Yayasan Markas Besar ABRI (Yamabri). Founded in 1995 with a combination of military and civilian ownership and initial capital of only Rp. 25 million ($11,250), it quickly expanded.129 In 2004, it was believed to have holdings in agribusiness, mining, communications, transport, and a convention hall.130 That year, the then TNI chief Gen. Endriartono Sutarto indicated that the total value of military businesses under TNI headquarters was no more than Rp. 100 billion ($11 million).131 Ministry of Defense: Yayasan Kejuangan Panglima Besar Sudirman (YKBPS). In 2006, YKBPS owned three universities, a high school, and hospital.132 A second foundation, Yayasan Kesejahteraan Perumahan Prajurit (YKPP), was involved in housing, while the ministry’s third foundation, Yayasan Satya Bhakti Pertiwi (YSBP), had numerous profit-oriented companies.133 |

Cooperatives

Military cooperatives form part of the national cooperative movement in Indonesia and, as such, are supposed to exist for the mutual benefit of their members and to be collectively controlled by these members, as well as by a national law on cooperatives.134 Like military foundations, however, military cooperatives have strayed far from their stated purpose. Initially established with troop welfare in mind—to provide subsidized commodities, such as rice, to soldiers and families—they soon became a vehicle for business ownership. The business activities of military cooperatives have tended to receive less scrutiny than those of military foundations. This has helped feed the often-false perception that military cooperatives merely serve as discount stores for the troops.135 Yet many cooperatives actually raise revenue not only from membership dues but also from wide-ranging business activities, including investments in private companies.136 Military cooperatives, for example, have owned stakes in numerous hotels and a cargo company.137 As with foundations, many are privately held companies so financial data can be difficult to obtain.

Table 2: Businesses Owned by Military Cooperatives

|

Service Branch |

Number of Businesses |

Internal Capital |

External Capital |

Dividend |

|

Army |

923 |

Rp. 169 billion ($17 million) |

Rp. 38 billion ($4 million) |

Rp. 13 billion ($1.3 million) |

|

Air Force |

147 |

Rp. 40 billion ($4 million) |

Rp. 9 billion ($900,000) |

Rp. 4 billion ($400,000) |

|

Navy |

124 |

Rp. 95 billion ($9.5 million) |

Rp. 8 billion ($800,000) |

Rp. 4 billion ($400,000) |

Source: Ridep Institute, Practices of Military Business, citing statistics from the planning bureau

of the Ministry of Cooperatives, Small and Medium Enterprises, 2001.138

The cooperatives of the military exist for each service branch and follow the territorial command structure. In the case of the army, for example, the Army Parent Cooperative (Induk Koperasi Angkatan Darat or Inkopad) corresponds to army headquarters, the Army Central Cooperative (Pusat Koperasi Angkatan Darat or Puskopad) to the regional military command, and the Army Primary Cooperative (Primer Koperasi Angkatan Darat or Primkopad) to the sub-regional military command level. District level offices and local posts also exist. Military cooperatives for the other services include Inkopau and Primkopau, in the case of the air force, and Inkopal and Primkopal for the navy.

An example provided below addresses military investments in forestry and agribusiness activity in East Kalimantan. In that case, an army cooperative had a minority share in a privately established company and also had its representatives on the board of the company, so the business ties were formalized. Informal business ventures are addressed separately in this chapter, in the section below on military alliances with the private sector, which includes the informative example of a military cooperative involved in coal mining activities.

Example 1: Military Investments in East Kalimantan

Military ownership in private companies is often hidden, but with assistance from NGO colleagues in the area Human Rights Watch was able to trace military interests in forestry operations in an area of East Kalimantan, near the border with Malaysia. The case of a series of military companies that held investments in the regency of Nunukan offers insight into military involvement in business.139 It also sheds light on some of the negative social and environmental consequences of this activity. Over the years, officials and local residents have accused military-associated businesses in the area of contributing to illegal logging, environmental destruction, and social tensions.

Military Stake in Forestry Operations

In 1967, citing “national security considerations” in the wake of a border dispute, the Indonesian government granted a military-owned company, PT Yamaker, concession rights on a huge tract of land covering more than one million hectares along the Indonesia-Malaysia border.140 With this move, it dispossessed indigenous communities of their customary land.141 It also set in motion a pattern that would persist for decades: military economic interests in the forestry sector would take precedence over the interests of local communities.

For decades, Yamaker grossly mismanaged the land. Local indigenous communities charged that overlogging by Yamaker disrupted their livelihoods and traditions and left “only forests with no trees.”142 The communities experienced additional hardship when Yamaker blocked access to the land, which it did routinely on the pretext of security.143 After the downfall of the Soeharto government in 1998 that ushered in the reformasi era, the new government investigated and exposed massive timber smuggling by Yamaker.144 The then minister of forestry and plantations, Muslimin Nasution, denounced the company for conducting its business in an illegal manner, failing to promote the welfare of area residents, and having “plundered [the forests] on a vast scale.”145 Acting on those findings, in 1999 the government revoked the entire Yamaker concession.146

The military nonetheless retained strong ties to that land. The new concession holder, the state-owned timber company Perhutani, partnered with the Inkopad army cooperative that had logging operations within the ex-Yamaker site.147 The military also provided security to Perhutani.148 Rather than directly engage in logging operations in the area themselves, the military instead partnered with foreign investors from Malaysia for that purpose.149

Military-Private Partnership

In 2000, Inkopad’s economic stake in the ex-Yamaker land deepened further. That year it partnered with a Malaysian company, Beta Omega Technologies (BOT), that planned to develop an oil palm plantation and processing factory on land in and near Nunukan regency. Inkopad became part-owner of the BOT subsidiary set up in Indonesia, Agrosilva Beta Kartika (ABK), and had several representatives on its board.150

These military connections helped the new company secure permissions and negotiate further deals.151 ABK gained the local government’s approval to cut timber on the land to prepare it for palm oil planting.152 Local officials said they expected the company to clear some 150 thousand hectares of land in the regency.153 From an early stage, it was clear ABK planned to log the area and sell the resulting timber. To assist ABK, the Nunukan government agreed to facilitate a minimum production target of fifty thousand cubic meters of lumber per year.154 (The then Nunukan regent also signed a contract to gain a partial ownership stake in ABK, though it remained unclear if he did so in his individual or official capacity.)155

These plans upset local indigenous communities living in the Simenggaris area, a forested zone in the interior of Nunukan regency along the border with Malaysia. A letter signed by some twenty community leaders outlined their concerns. They objected to the palm oil project on the grounds that it threatened to destroy the forest on which they depended for food, wood, and traditional medicinal plants.156 In addition, the collection of non-timber forest products such as rattan by local communities was an economic lifeline, second in importance only to agriculture, and they derived additional income from occasional logging activities in the forests.157 Nunukan residents already had the experience of severe forest depletion from logging operations in the area.158 The leaders of the area also urged that the project not move forward without proper consultation and the consent of the community.159 The leaders expressly opposed the involvement of the military in logging activities, stating “We are no longer willing to endure the same experience as [we had] with PT Yamaker.”160

Fears about the potential for overlogging were also informed by suspicion that the oil palm project might be nothing more than a cover to clear-cut forested areas for a quick profit, with no plantation ever being built. The practice has been prevalent enough in Indonesia to have earned a nickname, the “plantation hoax.”161 NGOs have estimated that only 10 percent of the three million hectares of East Kalimantan forest allocated to oil palm concessions has actually been converted into working plantations.162 Specialists who examined Nunukan’s soil as part of an independent environmental study determined that it was generally not suitable for oil palm.163 In addition, the conversion of forest to other uses, including oil palm plantations, contributed to the degradation of Nunukan’s forests. A related study found that about one-quarter of the primary forest in Nunukan’s formerly lush river basin had been lost over a seven-year period.164

Nunukan officials declared in 2001 that ABK’s Malaysian parent company BOT would invest at least $4.3 million to build an oil palm plantation and factory in the area, and that the project would employ as many as thirty-five thousand workers locally.165 Ignoring community concerns and requests for consultation, in mid-2001 the then regent gave the Inkopad army cooperative and ABK permission to proceed with the project.166 Community members issued protest letters to no avail.167 Later that year ABK contracted a Malaysian firm to clear land in the vicinity of Nunukan regency and market the timber on its behalf.168

A Pattern Repeats

By mid-2004, a new regent complained publicly that authorities in the region had granted logging permits too readily to unnamed forestry companies that promised to invest in oil palm plantations but instead only cut trees for export to Malaysia.169 He accused these companies of destroying some twenty-five thousand hectares of forests in Nunukan and contributing to the problem of illegal logging.170 The regent also pointed to a social cost. According to him, the episode sparked tensions and social unrest as people grew frustrated over promised plantation jobs that never materialized.171

The events that followed indicate the regent was referring to ABK. The contractor working for ABK was unable to renew its timber license after April 2004.172 The parent company in Malaysia, BOT, did not respond to questions from Human Rights Watch, but according to its joint-venture partner, Inkopad, ABK ceased operations on July 9, 2004, and subsequently lost its permits.173 In August 2004, regional authorities said they would investigate the regent’s allegations before taking action against any company.174 In December 2004, NGOs have reported, an official Department of Interior investigation concluded that ABK had engaged in extensive illegal logging and cross-border timber sales.175 That same month, the public record shows, the Indonesian Department of Forestry withdrew ABK’s permit.176

In an echo of the Yamaker experience years earlier, a military-linked company once again had been accused of breaking the law, causing environmental destruction, and contributing to social upheaval, and the only penalty was eventual loss of its concession rights. To Human Rights Watch’s knowledge, the military entities were not otherwise punished for their involvement in illegal activity, the individuals involved did not face prosecution, and the local community was not compensated for the damage done to the land.177 Inkopad told Human Rights Watch that it relinquished its shares in ABK and returned them to the parent company, BOT of Malaysia.178 The army cooperative declined to address its role in logging activities, land disputes, or environmental concerns associated with its business investment in Nunukan. On this point, its written response to Human Rights Watch stated, “Inkopad is no longer connected to problems related to [the planned] palm oil plantation in Simenggaris [area], Nunukan regency, East Kalimantan.”179

The issue was unlikely to end there, however. In 2005, the Indonesian government announced a plan to develop the largest oil palm plantation in the world along the Malaysia-Kalimantan border area.180 Nunukan was one of several regencies anticipated to host the massive plantation.181 Environmentalists, international officials, and even the palm oil producers association lined up against the project.182 In response to critics, the Indonesian government announced that it would reduce the size of the planned plantation, and avoid placing it on land designated for an international conservation initiative to preserve the area’s biodiversity, but that it still intended to move forward with the project in the Kalimantan border area.183 There was also controversy over the prospect that the project would provide a new excuse for the military to engage in forestry activities under the pretext of security.184 Human Rights Watch learned independently that the military had a stake in several forest concession areas elsewhere in Kalimantan that were slated for conversion to oil palm.185

Military Collaboration with Private Businesses

Alliances with corporations or private entrepreneurs account for a vast part of the TNI’s extensive business interests. Often the military partners with foreign investors. Private businesspeople, whether domestic or foreign, have different reasons to enter into an alliance with the military. They may seek, for example, to curry favor with powerful individuals who can advance their business. The military’s ability to arrange government licenses or block competition has diminished in recent years, but particularly at the local level, military officers retain the role of gatekeeper. Businesspeople also choose to align themselves with the military to gain access to goods and services. For example, the military provides transport services on military vehicles for a fee, leases out land, and trades in items such as fuel, timber, and coffee.

In an example described to Human Rights Watch, in 2004 a private business operated on military-owned land in Jakarta, for which the owner paid a monthly fee of Rp. 30 million ($3,300) directly to the unit. When he refused a demand by a military unit to raise the monthly fee, the unit shut down his business until a compromise was reached. The monthly payments went directly to the unit without being reported to public accounts.186

“Acquaintance Funds”: Private Contributions to the Military

The military’s alliances with business also can involve solicitation for contributions. Businesses raise money for the military for operations and provide in-kind support, such as vehicles or office equipment.187 In one example that was publicly reported, a developer provided land and buildings worth Rp. 18.5 billion ($1.95 million) to locate an army base inside a West Java industrial zone known as Jababeka. The donation made good business sense, an official of the industrial zone argued, since the presence of military personnel “can deter people from carrying out crimes here.”188

In other cases, an analyst explained, “[t]he local military commander just picks up a phone to get money [from business patrons].”189 The proceeds from these informal arrangements are sometimes referred to as “acquaintance funds” or “help from friends.” Lt. Gen. (ret.) Agus Widjojo acknowledged to Human Rights Watch that “it happens that business people make contributions” but stated that such arrangements have become less common than since the late 1990s: “Then it was easy [for a military officer] to approach a business to say what you need. Not now. The police are taking over the roles outside of defense.”190

Payments for Security Services

The Indonesian military makes itself available to provide security services for private interests. Different military units earn money by forming private security companies, and individual commanders charge a fee to loan out their troops as private guards.191 Some military officers who arrange such security services are later hired on by the companies they protected, to serve as security managers for company facilities.192 More famously, the TNI provides security to large multinational companies. In Indonesia, companies that operate facilities that the government has declared to be “vital national assets” are required to have protection. In practice, it has usually been the TNI that fills this role, despite a 2004 presidential decree that officially shifted the responsibility to guard such facilities to the police.193 For example, Indonesian authorities certified in January 2006 that the TNI would guard the facilities of three companies because neither the company nor the police could ensure adequate security.194 The reliance of major companies, particularly in the extractive sector, on state security forces (military and/or police) to protect their installations in remote and dangerous locations around the world can be rife with problems if the arrangements are not carefully managed.195 In Indonesia, questions surrounding company payments for military security are acute because of the armed forces’ record of corruption and human rights violations.

Companies can come under strong pressure to underwrite the expenses of military forces assigned to protect their facilities, so they do not always feel they have a choice. A former international executive commented to Human Rights Watch in frustration: “The way Indonesia sets up funding of the police and military is one grand national extortion racket.”196 A former employee of a multinational company offered this view to a researcher:

It is true that the Indonesian military is underpaid and under-equipped, and the housing they are provided is terrible. But is it the company’s place to subsidize the Indonesian military?197

This same person referred more directly to financial demands made by the military:

The problem was never with Jakarta as such, not with the military hierarchy there. The biggest problem has always been with the local military. Basically once we started to pay we were backed into a corner. The demands always came in for more money.198

Moreover, Indonesian troops often are accused of using intimidation and violence in the course of “protecting” private companies. (See “Freeport’s Security Arrangements,” below.) In one example, a pending 2001 lawsuit accuses ExxonMobil of complicity in gross abuses allegedly carried out by Indonesian security forces in and near the site of the company’s operations in Aceh, while the company strongly disputes the claim that it bears any responsibility.199 A coalition of environmental and indigenous rights groups described an incident in North Maluku in late 2003 in which they alleged that armed soldiers paid by a mining company delivered written notice threatening protesters with arrest if they did not leave that company’s mine site. 200

Freeport’s Security Arrangements

A well-known case of security arrangements involving the Indonesian military and police is that of U.S.-based mining giant Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Inc., which has extensive operations in Papua through its subsidiary, PT Freeport Indonesia.201 The TNI has had a presence alongside Freeport for decades,202 but the security presence has expanded considerably over time: as of 2005, more than 2,400 government security personnel (military and police) were located in the general area of Freeport’s operations.203

Security-Related Controversies

Freeport’s security arrangements have been controversial in a number of respects. First, Freeport’s ties to the military have led to accusations of complicity in human rights abuses by these forces. In the mid-1990s, troops at the mine site allegedly used company vehicles, offices, and shipping containers to transport and detain people they then tortured or killed.204 The company said it bore no responsibility for how its equipment was used by the military.205 Freeport’s human rights policy, adopted years after these events, explicitly recognizes the risk that military or police personnel may misuse company equipment and facilities to commit abuses.206

Second, there has been widespread speculation that the military intimidated Freeport into providing financial support at its Grasberg mine in Papua.207 The New York Times has repeated claims that the August 2002 killings of three Freeport employees in an ambush near the town of Timika may have been carried out by soldiers to ensure the continuation of paid security arrangements, as initially suspected by police.208 The TNI has disputed such claims in the strongest terms,209 Freeport has said it has no independent knowledge of who perpetrated the ambush,210 and a joint investigation by the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the Indonesian police did not find evidence of military involvement. The allegation resurfaced after the FBI’s prime suspect was arrested, together with several other Papuans, in January 2006.211 The suspect confessed to firing on the convoy of Freeport vehicles but also sought to implicate the military in the crime. According to his lawyer, a soldier provided the bullets used in the ambush and three men in military uniform also took part in the ambush.212

Third, serious questions have been raised regarding the financial ties between the company and the Indonesian security forces. Following the Timika killings, investors concerned about the company’s links to the military in Indonesia successfully pressured Freeport to reveal its spending on security. The company first publicly disclosed this information in 2003 and has reported annually since then.213 By the end of 2005, the company’s total spending on the military and police had topped $66 million.214 Much of the company’s support was provided in-kind, in the form of barracks, transport, food, and other such items, but Freeport also provided financial support. In explaining these payments, Freeport has said, “At the [Indonesian] Government’s request, we provide financial support to ensure that [its] security personnel (the military and police) have the necessary and appropriate resources to provide security for our operations.”215 The company, however, has not responded to queries seeking to establish to whom it made the payments and whether the payments went to government accounts.216 When it first disclosed its security payments, in 2003, a spokesperson for Freeport’s Indonesia subsidiary stated:

Many were shocked when they found out that we allocated millions of U.S. dollars to security personnel to guard the company, because they thought that we gave it in cash. But it is not like that because we allocated the funds to several posts, of which only a small amount was given to soldiers in cash as allowances.217

Investigative reports published in 2005 by the NGO Global Witness and the New York Times, by contrast, suggested that Freeport directed a large portion of its security payments to individuals.218 These reports alleged that the company had made large, direct payments to individual Indonesian military and police officers, as well as to units in the field. The New York Times, citing company documents it obtained and verified as authentic, said such payments totaled about $20 million from 1998 to 2004.219 The Times reported that the company doled out large sums of money that it recorded under accounting categories such as “food costs” and “monthly supplement,” but the bulk of the funds in fact were at the personal disposal of the commanders.220 Freeport asserted that the Times “mischaracterized the support we provide for Indonesian security forces and ignored the practicalities of conducting business in a remote area.”221

Indonesian military officials acknowledged that the company had provided assistance and confirmed that it was circulated to units in the field and did not go to the armed forces “as an institution.”222 The TNI has argued that the deployment of soldiers at the Grasberg mine and other designated vital facilities was in keeping with the duty of the TNI and took place upon the request of the companies involved, the regional governments, and the national police.223 Officials also have maintained that the government covers the essential costs associated with troop deployments, and Freeport provides additional support “without obligation.”224 Regarding Freeport’s financial arrangements with the military, the TNI has stated that “institutionally the TNI has never received security money from Freeport but our members who were assigned there did receive money from the company as logistics funds.”225

Such admissions helped propel the call by Global Witness for an investigation into possible bribery-related charges against Freeport under the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.226 After Indonesian officials indicated that direct payments to officers and soldiers could constitute corruption under Indonesian law, in early 2006 U.S. authorities initiated “informal inquiries.”227 Freeport staunchly defended the legality of its security arrangements and said it was cooperating with these inquiries.228 The Indonesian defense minister also indicated that he would ask the armed forces inspector general to open an inquiry.229

Freeport’s payments to the police have received less attention but raise similar issues. Global Witness and the New York Times cited examples of cash payments to senior police officials in Papua. Earlier published accounts suggest that the company did not find it unusual to be solicited for funds. According to a 2001 press account, a member of Freeport Indonesia’s board of directors, Prihadi Santoso, received a request for a Rp. 100 million ($10,000) loan from a person falsely claiming to be the then Papua police chief. Prihadi reportedly acted to authorize the requested bank transfer but later cancelled the remittance after the police chief’s office denied having issued the request.230 Freeport declined to respond to a question from Human Rights Watch about the incident.231 Company payments to the police are likely to receive greater scrutiny if the TNI withdraws from the Freeport mine area, as it has said it intends to do, and the police increase their presence.232

Freeport’s Perspective

Freeport has had little to say publicly, but a spokesperson has denied that it made inappropriate payments:

We don’t bribe. We do give assistance to the military, not in cash, but in the form of field equipment such as hand talky [portable two-way radio], cars, food….All payments are transparent and reported to the New York Stock Exchange. And assisting security personnel on duty is just normal. If you give some food to your starving guard, that is normal, right?233

A former Freeport executive familiar with security arrangements in Indonesia told Human Rights Watch that cash disbursements, made by bank transfer or check, accounted for about 15 percent of the total funds Freeport spent on the Indonesian security forces (the rest being used for in-kind goods and services).234 According to this source, the money was used for three purposes:

- “Small per diem payments” to supplement troop salaries. For a time, the payments were made to local commanders, but after the company insisted that the units establish bank accounts Freeport subsequently transferred funds to those accounts. Due to an “administrative mislabeling” some of these cash payments were listed as food costs in the company’s accounts until this practice was corrected.

- Reimbursements for administrative and logistical costs incurred by the military units in the field, such as for communications or use of helicopters, that the company provided in view of its assessment that “the [budgeted] money out of Jakarta is not enough for normal operations.” The company’s payments for this purpose amounted to approximately $1000 to $1500 per month for the regional military command (Kodam).

- Financing for individual “development” projects requested by the military, such as for hospital renovations. The company performed spot checks on about one-in-five of the projects.235

The former Freeport executive also maintained that the flow of funds to the military was governed by procedures outlined in a “written support agreement,” or, as other Freeport executives described it, “a contract with the military of the [security] relationship.”236 That document was submitted to the military commander in Jayapura, capital of Papua province, as well as to his police counterpart, the executives said, but was returned unsigned.237 The former executive maintained that the provisions of the unsigned agreement were nevertheless in effect and had been adhered to by both sides.238

The former executive defended the decision to bypass military headquarters in Jakarta by stating that corruption in the chain of command would prevent the funds from reaching the troops. Making the payments through commanders in Papua, he argued, “helped us and it helped them. We could avoid the extortion and extracurricular activities [by the military] and they could close the gap between what they needed and the available funds.”239 Asked why the company withheld details about its payments to individuals by only reporting aggregate amounts, this person said he could not be sure but thought that Freeport’s top management did not want to draw additional attention to an issue that already was “a magnet for controversy.”240

The former executive stated that the company made its security arrangements bilaterally, through a direct relationship with the military on the ground rather than through civilian government structures, because there was no government regulatory authority to fill that coordination role for the mining industry.241 He also repeated company claims that Freeport’s financial support to the military (and police) was a requirement of its Contract of Work (CoW) signed with the Indonesian government. Freeport’s spokesman, Greg Probst, explained the company’s rationale in 1999:

The original CoW [from 1967] was less specific in these areas [related to the relationship with the military] than the 1991 CoW. However, in a review of this issue, our Indonesian outside counsel found that the provisions of our [1967] CoW must be read in context with Indonesian law and that the two together provide a clear obligation on the part of [Freeport] to provide logistical and infrastructure support to the Government, including both military and civilian personnel, in all areas in which the government cannot supply such services.242

This issue has been under dispute. The author of a book on Freeport as well as the New York Times reported that the CoW has no language that requires security payments.243 Human Rights Watch’s understanding is that the CoW, as updated in 1991, contains only a general reference that the company “has been and will continue to be required to develop special facilities and carry out special functions for the fulfillment” of the CoW.244

Conclusion

Freeport has said it wishes to avoid controversy but it instead appears to invite it by what it says and declines to say publicly. On key issues related to its security arrangements in Indonesia, the company has offered public explanations that are open to question. The company has maintained that it is required to provide financial support to Indonesian security forces but has not provided sufficient evidence to bolster that claim, even when directly asked.245 Government officials, meanwhile, insist that the company’s support is entirely voluntary.246 It is also difficult to reconcile the company’s position that its support is fully compliant with the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights, a set of international guidelines designed to ensure that company security arrangements respect human rights.247 The Voluntary Principles presume maximum transparency for security arrangements, including any payments, subject only to overriding safety considerations or security situations.248

Moreover, if Freeport’s decision to make payments at the local level and to seek to avoid scrutiny by withholding details about those payments was intended as a way to avoid corruption and also the glare of publicity, then it failed on both fronts. Payments to commanders and units in the field, which the former executive maintained were designed to avoid centralized corruption, served instead to raise allegations of local-level corruption by Freeport. By the same token, the company’s unwillingness to fully disclose its payments at the outset, and when asked subsequently, has encouraged suspicion that it has something to hide. The misidentification of payments, as food costs rather than cash transfers, also lends itself to the implication that employees had sought to cover up the company’s financial support. In short, Freeport’s actions were insufficient to avoid the potential problems it identified and instead created vexing new ones.

The wave of negative publicity surrounding the military’s ties to Freeport led Indonesian Defense Minister Juwono Sudarsono in early 2006 to offer to prepare official guidelines on companies’ security arrangements, including associated payments.249 An alliance of Indonesian civil society groups, however, strongly challenged the assumption that it was appropriate for companies to directly underwrite the military. They pointed out that such arrangements give the military an economic stake in internal security tasks for which the police have primary responsibility.250 The groups added that company payments compromise the country’s security forces, since they could cause these forces to put the interest of companies ahead of their duties to the public. Another criticism that often has been made, including by civil society groups, is that financial arrangements with companies provide a platform for military corruption and serve to undermine civilian control. It also often has been suggested, as in the Freeport case, that paid security arrangements create incentives for the military in the area to cause security disturbances so they can reap the financial benefits when they are called in to assist.251 In short, the military is in a position to create and sustain demand for its services. Concern over the potential for human rights abuse, as noted above, provides another reason for opposition to the military’s role in providing security to companies. A case described in detail below shows how troops from a military cooperative, brought in at the request of a mining company, used abusive tactics to keep unlicensed miners in line.

Example 2: Military Coal Mining and Human Rights in South Kalimantan

When PT Arutmin, an Indonesian-owned mining company with operations in South Kalimantan, was faced with illegal mining in its concession areas, it turned to the security forces for help.252 After the police response proved inadequate, the company engaged the military—through a loose partnership with an army cooperative—to help control illegal mining at its Senakin mine.

Army Cooperative Regularizes Illegal Mining

The role of the army cooperative was to act as an intermediary to help reduce the illegal mining activities of local residents who used heavy equipment to mine tons of surface coal. The active-duty soldiers who worked in the cooperative were to organize the unlicensed local miners and ensure they turned the coal over for delivery to the company. In exchange, the army cooperative got to earn a profit from the resale of the coal.253

Neither the army cooperative nor Arutmin responded to Human Rights Watch’s requests for information. A representative of the contractor for Arutmin’s operations at the Senakin mine, however, publicly explained the set-up under which the military (and police, at another mine location) organized illegal miners with the concession-holder’s permission:

I actually wouldn’t even call it illegal [mining] now. It is semi-organized subcontracting direct to Arutmin, who have now got the whole thing under control.254

Once the army cooperative had a financial stake in coal mining operations, it soon slipped into a realm outside the rule of law. Soldiers not only channeled to the company the coal mined by the illegal miners, as envisioned, but demanded bribes from the miners to allow black market coal sales. The army cooperative also exploited the miners. Soldiers demanded bribes, paid the miners a fraction of the value of the coal, and often did not pay them for months at a time. Moreover, the soldiers used coercion and violence to enforce their cooperative’s control. Miners told Human Rights Watch of beatings and other abuse.255

The account here focuses on military abuses committed against coal miners who were controlled by the army cooperative under this arrangement. As explained to Human Rights Watch by several miners, the regional army cooperative for South Kalimantan, Puskopad B,256 issued permits to miners granting them permission to mine on the Arutmin concession,257 required them to sell the mined coal back to the cooperative for it to resell to Arutmin at a large profit, and used intimidation and force to keep the miners in line. This was lucrative business for Puskopad, which paid the miners only about half the market value for their coal (approximately Rp. 38,000 to Rp. 44,000 [$4.18 to $4.84] per metric ton, compared to the Rp. 75,000 to Rp. 85,000 [$8.25 to $9.35] local price on the open market in late 2004).258

The miners, however, had little choice since their status was tenuous. Despite the permits granted by Puskopad, with the presumed agreement of the company, the miners were still operating outside the law and were subject to arrest by police.259 One miner explained:

The Puskopad guarantee is not 100 percent. Since I have a work permit from Puskopad to mine on the Arutmin site, it’s almost like I’m a legal miner. But the police will come and say I’m not authorized.260

A third miner put it more bluntly:

The TNI takes advantage of the guarantees so they can get the fee for the coal, but they do not protect us from the police.261

Puskopad also facilitated illegal mining outside the agreement. Miners said they were able to pay Puskopad a fee (Rp. 13,000 per ton, or $1.43) so that Puskopad would not block them from selling coal they had mined on the open market.262 One miner explained:

If you don’t pay the royalty to Puskopad you can’t sell the coal on the open market. If you don’t pay the royalty you’d get taken away. Everybody knows you have to pay so no one even tries to sell [on the open market] without paying.263

Exploitation and Abuse of Miners

Miners who spoke to Human Rights Watch said these arrangements trapped them in an exploitative relationship with the army cooperative. They said that the low price the cooperative paid them for their coal, in combination with the various fees it charged, made it very hard for them to make a living. They also complained of payments that often were made months late, leaving them to live hand-to-mouth. Several of the miners felt they were being taken advantage of and some decided it was not worth it to mine for Puskopad on the Arutmin concession.

A former miner explained why he got out of the business: “There are too many procedures. You also have to give money, lots of it, if you want to mine there.”264

A more serious concern for the miners was that Puskopad enforced its economic interests with an iron hand, relying on intimidation and violence. All of the miners with whom Human Rights Watch spoke had been subjected to various forms of mistreatment by Puskopad. These cases arose when the miners acted in defiance of the permit arrangements or when they attempted to avoid the additional payments demanded by the cooperative for allowing the miners to sell coal on the open market.

For example, two miners said that Puskopad patrols forced miners to dump out truckloads of coal when they were caught leaving without having first stopped at the Puskopad office to pay the agreed fees.265 Another miner was detained for several hours in September 2003 for mining without Puskopad’s advance knowledge. He said an armed patrol escorted him to the Puskopad office, where the commander threatened to seize the miner’s equipment and demanded, “If you are in the Arutmin site you have to report to me.”266

Some of these encounters involved the implicit or explicit threat of violence. One miner said that on repeated occasions Puskopad patrols had threatened to shoot him and had beaten the drivers and laborers working with miners.267 Late at night in November 2003, as three miners and their crews were loading the coal they had secretly mined, some twenty uniformed and armed military personnel from the Puskopad post approached and immediately began threatening and beating them:

The commander (…) arrived. He threatened me. He said, “If you do anything you’ll be shot.” The guns were pointed at me, they were long guns [rifles]. The people in our group were beaten for around fifteen minutes until they were bruised. They used everything to hit them—their guns, their hands, their feet. I was in a car and they threatened to shoot me. They were all in uniform and had guns.268

He went on to describe that the miners and laborers were subsequently arbitrarily detained. They were taken to the Puskopad office, where the beatings continued:

We were held until morning but some people who were not taken that night were called in for questioning the next morning. About ten people were taken to the hospital for their injuries. One was beaten in the ears and lost his hearing. He still can’t hear properly. Mostly people had severe bruising, and in one case cuts to the face, from being hit with the butt of a gun. I wasn’t beaten but I was handled roughly and was threatened.269

Explaining why they had dared take coal out secretly, one of the miners said:

This happened because we had mined for three or four months and never were paid, so we went out that night to mine on our own to cover our expenses for that time.270

Late payments were a common complaint. The miners attributed the months-long delays to the arrangements Puskopad made to resell the coal back to Arutmin. They said that process involved the cooperative and company jointly measuring out the coal, combining it with the company’s stockpile, and processing payment, only after which would the miners be paid by Puskopad.271 As one put it, “Our community suffered over this because we couldn’t get the money and we weren’t able to eat.272

Military Denies Business Activity

In October 2005, the police chief for South Kalimantan ordered the police cooperative in the area, Puskopol, to suspend its involvement in mining activities out of concern that it had become a cover for illegal mining activity.273 As with the military cooperative, though in different locations, Puskopol was originally brought in by Arutmin to control illegal mining activities as an intermediary.274 Like the military cooperative, the police cooperative allegedly took over illegal mining activities at these locations and expanded them.275 The South Kalimantan police chief acted after a local NGO, the regional office of the Forum on the Environment in Indonesia (Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia, Walhi), urged him to crack down on illegal mining by his forces.276

There was no such crackdown by the military. In 2004 and 2005 the army cooperative declined to meet or discuss its role in coal mining activities with Walhi and Human Rights Watch, which worked together to carry out field research on the military’s business activity in Senakin. After Walhi wrote to the TNI chief in Jakarta in late 2005 about the situation in Senakin,277 it received a response. The response, issued by the commander of the sub-regional military resort command, or Korem, headquartered in Banjarmasin, South Kalimantan (known as Korem 101/Antasari) said the TNI had investigated the matter and found no evidence of wrongdoing.278 Ignoring the economic dimension of the army cooperative’s role in Senakin, the TNI investigators concluded that “Puskopad B is a partner of PT Arutmin in a non-technical operation to prevent illegal mining and the siphoning of coal.”279 Disregarding Walhi’s call for military personnel involved in illegal mining to be punished, the Korem commander’s report concluded:

Up to now there are no TNI personnel, specifically members of Korem 101/ANT, who participate in or are involved directly or indirectly in illegal coal mining activities.280

The commander’s rationale that the Puskopad cooperative simply acted to regularize illegal mining directly contradicted the statements of more senior military officials. When informed by Human Rights Watch of the activities of the cooperative in Senakin, military representatives at the TNI headquarters asserted: “This activity is definitely outside of [proper] cooperative activity and TNI activity so must be stopped and will be stopped.”281 The secretary-general of the Ministry of Defense responded similarly: “I agree that brokering is illegal for us [military personnel] and we have to regulate that. It’s not the military itself [that is responsible.]”282 Yet some six months after Walhi sent its letter to the TNI chief—which it copied to numerous other authorities, including the Minister of Defense and military officials at the headquarters, regional, and sub-regional levels, as well as the regional police chief—no such action had been taken. The only response was the Korem commander’s report to his superior that the cooperative’s activities did not constitute a business and therefore were not banned.

The willful failure to act to halt the coal brokering activity by TNI troops made clear that, despite the reassuring words, military business activities continued to be officially tolerated, and at times even justified, as they had been for years.283 The investigation into Puskopad’s activities in and near the Senakin mine apparently did have one effect: Within days of receiving the Korem commander’s response, Walhi was contacted by an Arutmin representative who said that the company had decided to end its cooperation with the military.284 As of this writing, it was not possible to determine if the situation had in fact changed on the ground in Senakin.285

Military Involvement in Criminal Activity

This section considers some of the main areas in which the military has been implicated in criminal activity. The presentation here is by no means exhaustive, given that military personnel have been accused of direct involvement in a range of criminal enterprises. Persistent patterns of illegal business activity by the military, often concentrated in sectors such as logging and mining, indicate that the problem is widespread. Across the country, units and commanders, not just low-ranking soldiers, are commonly implicated. In a number of cases it can be shown that their illegal businesses are known to their superiors, and only very rarely do the authorities act to enforce the law against these military personnel.286 These characteristics point to the structural nature of the problem of illegal military business.

At the same time, it must be acknowledged that some cases involve relatively isolated incidents by rogue individuals. Paid assassinations are among the most extreme examples of economically-motivated criminal acts by individual soldiers. One case involved the July 2003 murder-for-hire of a businessman in which his bodyguard, a moonlighting Kopassus soldier, was also killed.287 The marines who were convicted in the killings reportedly confessed that they had been paid Rp. 2 million ($237) each to commit the murder.288 Another case came to light in early 2005; this time an army soldier was identified as a suspect in a paid killing.289

Illegal Logging

Military involvement in forestry operations can include illegitimate activity by military enterprises, such as overlogging at concessions owned by military foundations or processing illegal timber at sawmills run by military commands.290 The example provided above (see “Military Investments in East Kalimantan,” above) offers one illustration of military-owned businesses that allegedly engaged in illegal logging. Also, local timber barons rely on regional military commands to use intimidation and violence to secure community acquiescence.291 These timber barons benefit from impunity thanks to their links to the security forces.292 A timber expert explained that the role of the military also extends to “providing protection for timber mafias or transport on military trucks or helping smuggle logs across the border or extortion—to seize legal or illegal logs.”293

The problem has been best documented with respect to the remote and conflict-torn regions of Indonesia. For example, a joint report by the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) and the Indonesian NGO Telapak spotlighted the pervasive role of the military “in every aspect of illegal logging” in Papua, where massive timber smuggling takes place. Two timber dealers interviewed by the investigators acknowledged paying dozens of soldiers to look after their illicit timber interests. The report also drew attention to alleged acts of military intimidation in support of an illegal logging operation.294

Prompted by the EIA/Telapak report on Papua, President Yudhoyono announced a crackdown on rampant illegal logging that he promised would not spare military personnel.295 He issued a presidential order against illegal logging that called on military personnel to help combat illegal logging.296 A handful of military personnel were among the hundreds reported to have been arrested in operations against illegal logging.297 Campaigners expressed disappointment that, in the end, many of those arrested were released without charge and that in most cases they had not been able to get information about the outcome of military trials.298 In one prominent case, previously mentioned, EIA/Telapak first reported to the authorities in 2003 that a military policeman was deeply implicated in illegal logging activities in Papua but no action was taken for two years. After the EIA/Telapak report was made public, this person was brought in for questioning, but Telapak researchers learned that by the end of 2005 he had been released.299

In addition to undermining the rule of law, military involvement in illegal forestry activity has been associated with human rights abuses. In Papua, for example, communities that dare protest military-backed logging activities have been accused of being separatists.300 They also have been directly victimized by soldiers who seize their timber for resale, sometimes using violence and intimidation tactics.301

Racketeering

Protection rackets provide another source of illicit income to military personnel who are involved. Military backers reputedly protect drug traffickers, gambling operations, and prostitution rings.302 As with other revenue sources, racketeering also is linked to military abuses. Human Rights Watch received reports that in 2004 soldiers smashed the windows and burned the property of those who refused their demands for protection payments.303

In Medan, North Sumatra, military involvement in crime is well-organized. Medan residents said that the protection rackets are regularized, with shop owners and trucks paying monthly fees and showing stickers designating which military group or associated gang supported them.304 A person who for years worked in Medan’s underworld told Human Rights Watch that the military was deeply involved “[e]verywhere in Medan where illegal businesses exist,” including in prominent roles as backers of illegal logging and the drugs trade.305

Military-Police Conflicts

Military engagement in the criminal economy has often brought soldiers into tension with the police. Welcome moves to give the police greater responsibility for internal security have had the unintended side effect of displacing the military from some of its lucrative money-making opportunities, including illicit ones. This trend has aggravated rivalries that at times flare up into violence. Clashes between the Indonesian security forces were a regular occurrence in the early 2000s, with at least a dozen incidents from 2001 to 2003.306 In late 2004, a member of the Brimob (“Brigade Mobil” or Mobile Brigade) paramilitary police commandos was killed and three others were seriously wounded in an armed brawl with TNI soldiers in Aceh that was reportedly sparked by competition over oil palm interests.307

The security forces also can come into conflict with each other when police, acting in their law enforcement role, interfere with the economic interests of soldiers. For example, soldiers and police clashed in 2002 in West Kalimantan after police reportedly moved to shut down a TNI-protected gambling operation.308 That same year a notorious military-police firefight, detailed below, was sparked by the arrest of a drug dealer who reputedly had military backing. In another, more recent example, in March 2005 a local army unit battled with Brimob police forces in Papua, reportedly when they attempted to crack down on illegal logging operations that implicated a TNI officer.309 As a result, it comes as no surprise that police officials complain about the difficulty of acting against the military.310

Example 3: Turf Battle in Binjai, North Sumatra

In September 2002 police in Binjai, North Sumatra arrested an accused drug dealer who allegedly operated with military backing. The suspect’s associates in the military sought to have him released and became enraged when the police refused. What began as a battle over authority between the police and the military soon took on more ominous dimensions: In revenge, the military unit organized an armed assault on the police station, setting off a shootout that engulfed the town for hours and terrified the townspeople. Some fifteen people were killed, most of them police officers, and at least four civilians were among the dead. Of the more than sixty people estimated to have been wounded, twenty-three were civilians.311

Drug Arrest Triggers Dispute

The dispute that erupted into armed battle was triggered by an incident in the police station the day before. A fight broke out when police refused a demand from a small group of soldiers to release a suspect. Angry soldiers attacked the police, cutting the ear of the commanding police officer, and police responded by firing on the assailants.312 Police then retaliated by severely beating two of the attackers who had not managed to flee; their bodies were “covered in bruises.”313

The suspect whose arrest was at the center of the dispute was a suspected drug dealer reputed to operate with military backing from Linud 100, an airborne reserve unit based in Binjai.314 A senior police officer in the town explained:

The suspect at the time of his arrest was protected by military personnel. There’s a lot of business activity going on. We know there are military people behind it.315

A lower-ranking police officer in the town commented further:

There were individuals from Linud who were doing illegal activities so there were some problems when the police would stop their activities, things like gambling and drugs. The Linud members aren’t directly involved but they back up these activities, provide protection.316

The Military Revenge Attack

Linud troops waited until the night of the following day to respond to the incident. Scores of troops in combat gear launched a major attack against the police station in the center of town, firing small arms, rockets, and grenades. They also blocked the entrances and exits to the town, obstructed access to the local hospital, and deliberately cut electricity, causing a blackout. After paramilitary police commandos from the Brimob barracks a few kilometers away were called in to help, the Linud soldiers engaged in a firefight with Brimob along the road then proceeded to attack the Brimob barracks located near the entrance to town.317

With the area’s police forces scattered, in hiding, and engaged in a shootout with the military, no one was left to defend the town’s population from the assault. A young man from Medan was fatally wounded at about 1 a.m. as he drove into Binjai with a group of friends. Soldiers who had set up a roadblock stopped the vehicle and shot the young man in the head. Eyewitnesses told the victim’s family that the bullet was shot at short range and after those in the car had identified themselves as civilians.318 Separately, a restaurant owner traveling by car was killed when the vehicle was fired on, and two other passengers in the vehicle sustained gunshot wounds.319 A cigarette vendor was wounded by a stray bullet and ordered taken to a military hospital.320 In other incidents, a civil servant died from a gunshot wound and another person suffered unidentified wounds.321 As many as twenty-three civilians sustained injuries in the attack.322

Police casualties were also high. According to police sources, eleven policemen (local and Brimob) were killed and thirty-seven were wounded.323 The TNI suffered fewer casualties. One soldier died and, by one count, four Linud personnel were wounded.324

After the Battle

The battle finally came to an end some twelve hours after it began, when top police and military officers arrived in Binjai to impose a truce.325 With many police officers still in hiding, a climate of lawlessness prevailed for several days and many people remained too scared to leave homes. Even two years after the incident, the residents of Binjai remain disillusioned with the TNI. Several townspeople told Human Rights Watch that they could no longer trust the military after troops sworn to defend the security of the nation had done the exact opposite.

Military and government officials issued strong statements of condemnation, temporarily shut down the Linud battalion, and announced that those responsible would be dishonorably discharged.326 But of the approximately 350 Linud soldiers that police said were involved in the attack (about half of the battalion),327 only twenty soldiers were dismissed and faced trial. The military prosecution of the twenty discharged soldiers, all of them of low rank, resulted in nineteen convictions and prison sentences of five to thirty months.328 The military court in Medan declined Human Rights Watch’s request for information about disciplinary action taken in response to the Binjai incident. Repeated visits to the military stations in Binjai and Medan also failed to elicit any information, but indications were that the more senior officers who oversaw the Linud battalion faced little consequence. The army transferred the Binjai battalion commander and five other officers to other locations and decided not to take immediate action against the regional military commander.329

Conclusion

The battle in Binjai stands as a particularly outrageous example of the negative consequences of military involvement in illicit businesses. There, troops effectively declared war on the police. The police in Indonesia have a well-deserved reputation for corruption, and competition over local spoils has given rise to numerous armed clashes between the security forces, but in this case the confrontation was sparked by an altercation between a few troops and policemen over a local drug arrest. The issue could have been resolved without bloodshed, but it exploded into a major battle because the military unit as a whole had already lost its integrity. It had learned to put self-interest above institutional duty, lacked respect for the rule of law, automatically resorted to violence to protect its turf and pride, and assumed it could do so with impunity. This arrogance was a legacy of the unit’s links to the criminal economy. A Binjai police officer offered a skeptical view on whether the military had learned any lessons from the experience: “The military are still involved in backing up illegal activities so it could happen again.”330

Military Corruption

Transparency International has identified Indonesia as the world’s sixth most corrupt country in its annual survey.331 The group ranked the Indonesian military as among the most corrupt public institutions in the country.332 The World Bank defines corruption as “the use of authority for private gain.”333 It includes in that definition, among other acts, an official’s acceptance, solicitation, or extortion of a bribe.334 Collusion, patronage or nepotism, theft of state assets, and diversion of state revenues are also considered to be corruption.335 Indonesian anti-corruption laws also encompass the abuse of power, causing financial loss to the state, and self-enrichment.336

Grand Corruption

Indonesia’s history offers many examples of military corruption on a major scale that involve relatively senior government officials. Often these relate to the sorts of collusive business practices and misuse of foundation funds described elsewhere in this report. Some other cases relate to individuals who take advantage of their position to take public funds for personal use. As one indication, over 100 cases of financial fraud reportedly were uncovered within the TNI in 2005.337 In early 2006 an army colonel and a private citizen were arrested on charges of conspiring to embezzle as much as $14 million from the army’s housing fund.338