<<previous | index | next>>

V. Attacks on Civilians Working for Foreign Governments

While most insurgent attacks in 2003 targeted Iraqi or multinational forces, by early 2004 insurgents began to attack so-called “soft targets” affiliated with the foreign forces in Iraq; namely, Iraqi and foreign civilians working for, or suspected of working for, the Multi-National Force or foreign governments. By far the largest number of victims has been Iraqis who worked as translators, cleaners, drivers and barbers for the CPA, the U.S. government or other governments in the coalition, as well as those suspected of giving information to foreign governments. The total number of victims is unknown, but press reports and anecdotal evidence reveal a pattern of threats and attacks, including the murder of civilians who work with foreign governments in any capacity.

According to those claiming responsibility for attacks on these civilians, the victims were valid targets because they were collaborating with the foreign powers in Iraq. Even though they were not directly engaged in hostilities, they were viewed as aiding and abetting foreign forces by providing services to a government or military. As a matter of international humanitarian law, any attack against civilians who are not directly participating in hostilities is prohibited.

The attacks are intended as punishment for perceived collaboration and as a warning to others who might consider such work. On October 23, 2004, for example, Ansar al-Sunna posted a video on its website that showed the “confession” and execution of Saif `Adnan Kan`an, who said he was a vehicle mechanic at the U.S. base in Mosul. “I am telling anybody who wants to work with Americans to not work with them,” he said. “I found out that the mujahadeen have very accurate information [and] strong intelligence about everything. They are stronger than I thought.” He was then beheaded.148

A well documented target among this category of victims is Iraqi and foreign civilians working on U.S.-government-funded reconstruction contracts. According to a report by the U.S. government’s Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction, insurgent groups killed 276 civilians working on such contracts up to March 31, 2005.149 Approximately 100 of these civilians were U.S. citizens. The attacks have continued apace since the report, with armed groups killing seven contractors, injuring eleven and kidnapping up to sixteen in August, according to the U.S. Project and Contracting Office in Baghdad. Of the thirty-four contractors who were killed, wounded or went missing that month, thirty-two of them were Iraqi and none was American.150

Another targeted group is translators who worked for the U.S. government, the military or the CPA. According to one press report, insurgent groups killed fifty-two translators

in Baghdad, al-Falluja and al-Ramadi between January and September 2004, although the report did not specify how they were killed. Forty-five of the deaths were in Baghdad.151

In one case documented by Human Rights Watch, armed men gunned down four young women, all of them Christians, as they drove home from work as cleaners on the U.S. military base at Mosul airport. According to family members of the victims, the three women in the back seat were killed, while the driver and woman in the front survived.

Tara Majid Boutros, aged nineteen, was one of those killed (see photo below). A literature student at the university in Mosul, she was working at the base for the summer to earn extra money for the family. Her father suffered from kidney stones and was unable to work. According to family members, the four women commuted every day from their homes in Bartala, just outside Mosul, to the airport base. One of them told Human Rights Watch what happened on August 31, 2004:

Usually she [Tara] came home at 4:45 p.m. and we would wait for her because the situation in Mosul was bad. On that day she didn’t come at 4:45 or 5:00. By 5:10, I was waiting in the street, and I thought to call the family of the driver. When I called, I heard crying, and someone said they had been attacked. You can imagine how I felt. I dropped the phone. I was in bare feet but I ran to the family of the driver, which was one kilometer away.152

At that point, another family member went to Mosul with a friend to look for Tara and the other girls. They found her in al-Razi Hospital, badly wounded from bullet wounds to the lower back, hip and buttock and in need of blood. She died just after they arrived.153 The death certificate stated the cause of death as “rupture of the heart and two lungs as a result of gunfire.”154

The two other victims were the sisters Taghrid and Hala `Ishaq. According to the woman in the front seat, who received a minor shrapnel wound in the back:

We were driving along, and we had just passed the light near the al-Karama police station when a car came from behind and hit us on the driver’s side. I don’t remember the kind of car, but it was milk colored. I think they were three, a driver and two men in the back. Our driver stopped to see who had crashed into us. Then he saw they had weapons so, although he had slowed down, he said “Put your heads down!” and he sped up. He sped up and the other car followed us but they had a better car and they caught up to us and cornered us on the side of the street. They were shooting the whole time.

I

ducked and stayed down until the shooting stopped. I got a piece of metal from

the car in my back. When I lifted my head, I saw the driver move, and he was

asking the girls if they were hit. He was holding his side because he was hit. I

didn’t feel the fragment yet, but we turned around and I saw the three girls

were covered in blood. Only Tara said “Oh!” from the pain. We got out of the

car and opened the back door to see if we could help them. Tara was right

behind me so I asked where she was hurt. She only said, “Get me to the

hospital.” We tried to stop some cars to help us and finally a car stopped…

Before they drove away, when they pulled Tara from the car, Hala slumped over. Half

of her was in the car and half outside. It was clear she was dead because she

was hit in the head and half her brain was out. So passersby lay her on the

street and covered her with a scarf. I called Taghrid and she moved her hand so

people said she was still alive.155

I

ducked and stayed down until the shooting stopped. I got a piece of metal from

the car in my back. When I lifted my head, I saw the driver move, and he was

asking the girls if they were hit. He was holding his side because he was hit. I

didn’t feel the fragment yet, but we turned around and I saw the three girls

were covered in blood. Only Tara said “Oh!” from the pain. We got out of the

car and opened the back door to see if we could help them. Tara was right

behind me so I asked where she was hurt. She only said, “Get me to the

hospital.” We tried to stop some cars to help us and finally a car stopped…

Before they drove away, when they pulled Tara from the car, Hala slumped over. Half

of her was in the car and half outside. It was clear she was dead because she

was hit in the head and half her brain was out. So passersby lay her on the

street and covered her with a scarf. I called Taghrid and she moved her hand so

people said she was still alive.155

The woman and driver helped get Taghrid and Tara to the hospital. Taghrid was dead on arrival but Tara was still alive, the woman explained:

While there, they brought Tara for x-rays. Two of the nurses were called away, there was only one left, so he asked me to help him put Tara in the right position for x-rays. At that point, Tara was still able to speak. She said, “Help me.” I said, “Hold on, the doctors are coming.” But then, all of a sudden, she stopped speaking… They had been giving her blood. After the fourth pint, the x-rays returned. There was a bullet in her urinary tract. There was internal bleeding. They said, “We can’t help her.”

Tara’s family tried to speak with the police in Mosul but they were repeatedly rebuffed, they said. “When I tried to speak to the police, I said ‘they [the attackers] are terrorists,’ but they told me, ‘no, they are mujahadin,’” one of the family members said.156 The family filed a complaint with the police ten days after the attack. The police took witness testimonies, and then one of the officers asked the family bluntly: “What got [her] into this mess? You know the mujahadin don’t accept [working for the U.S.].” The U.S. military called the family to the airport base, where they were asked if the family suspected anyone in the girls’ death, and whether the family had any enemies. The family said no. An officer said they would contact the family again in fifteen days, but the family has not heard from them since.

In a case involving Christians, gunmen shot and killed a man named Isho Nissan Markus, aged twenty-three, and his niece Ramziyya, aged twenty-one, while they went to work at the laundry in the Presidential Palace in Baghdad, which was occupied by U.S. forces. According to a family member who wanted to remain anonymous, his two relatives, together with three others named Ramiz, Rami and Duraid, traveled every day by taxi to work in Baghdad’s Green Zone. On June 7, 2004, unknown assailants attacked them on the way to the family home. The family member said:

We were at home at the time and we heard the commotion outside, because the killing took place near our house, just at the end of the road. When I got there I saw Ramziyya. We took her to the Al-Yarmuk Hospital. She had seven bullets in her back, her waist and her left hand. Isho had received three bullets to the head and he died instantly. There were also two other bullet wounds to his chest. Ramziyya was still alive when I found her but she died around 12:30 p.m. after we had arrived at the hospital.157

According to the family member, the other passenger Duraid also died, while Ramiz and Rami were wounded. According to the Assyrian Democratic Movement, Iraq’s largest Christian political organization, three men died in the attack: Isho Nissan Markus, Duraid Sabri Hanna and Hisham `Umar.158 It is possible that Hisham `Umar was killed on the street as a bystander rather than in the car.

In a separate incident on the same day, the Assyrian Democratic Movement said gunmen shot and killed a driver and three Assyrian Christian women returning from work at the CPA, Alice Aramayis, Ayda Petros Bakus and Muna Jalal Karim, but Human Rights Watch did not confirm this report.159

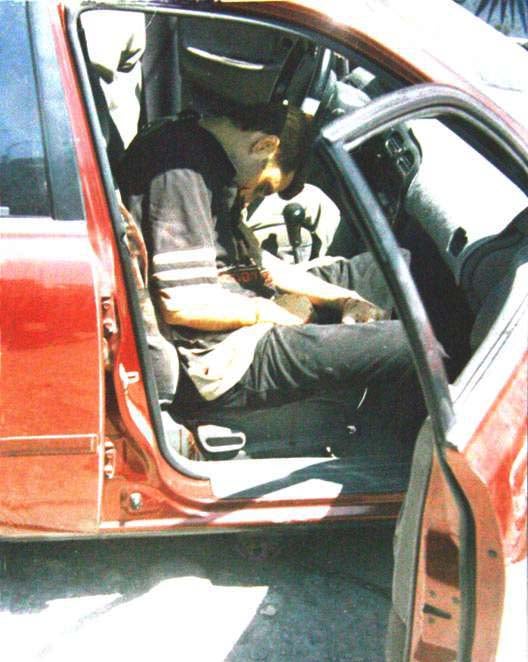

In a third case involving Christians, insurgents killed two brothers whom they suspected of working for the United States military, Khalid and Hani Boulos Tu’ma Sliwa, aged thirty and thirty-three, respectively. Gunmen shot and killed both men in their car in Mosul on September 2, 2004 (see photos).

According to family members, the problems began in mid-2004 when insurgents captured a Christian from Mosul, who they believed was giving information to the U.S. military about insurgent activity. An armed group called Salah al-Din al-Ayyubi soon distributed a video around Mosul called “The Spies,” in which the captured man “confessed” to being an informer for the United States. In the video, viewed by Human Rights Watch, the man names others as informers, including the five brothers of the Sliwa family, before being beheaded with a large knife.

On June 1, 2004, one of the Sliwa brothers who wished not to be named was walking home from a café with four friends, two Christians and two Muslims, when masked men opened fire on them with pistols. The brother said he was hit in the left arm and stomach.160 Human Rights Watch saw scars in both places as well as medical records from the al-Zahrawi Teaching Hospital in Mosul attesting to the injuries.

The injured brother said that acquaintances from his al-Sa`a neighborhood in Mosul, where the family had lived for five generations, had threatened him before, wrongly asserting that he was working for the U.S. military, but this was the first physical attack. Graffiti in the neighborhood called for Christians to be killed, he said, and the beheading video by Salah al-Din al-Ayyubi, mentioned above, was widely available in Mosul markets. According to the brother, neither he nor anyone in his family worked for the U.S. government, but Human Rights Watch did not confirm this claim.

Six weeks after the first shooting, gunmen again shot and wounded the brother. Unknown men had entered his neighborhood, he said, and when he went out to look, they opened fire with Kalashnikov assault rifles, hitting him in the right thigh and left shin. Three other men nearby were also hit.

Unknown gunmen in Mosul shot and killed these two brothers,

Khalid and Hani Boulos Tu’ma Sliwa, aged thirty

and thirty-three,

respectively, on September 2, 2004, apparently because they were

thought to be giving information to the U.S. military about insurgent

activity.

© 2005 Human Rights

Watch

The injured brother interviewed by Human Rights Watch left Mosul, but the other Sliwa brothers stayed behind. On September 2, relatives said, Khalid and Hani were pulling their red BMW out of a garage when approximately fifteen armed men blocked their path and opened fire with automatic rifles, killing them both. The family went to the police station in Mosul’s Khazraj district and gave the names of the people who had threatened them in the past, but said the police told them to go home. As of February 2005, the family had no information on whether the attackers had been arrested. “We went to the police but it was no use,” the brother said.

The entire family moved to `Ain Kawa after the murders, where they lived in small rented house. “We are threatened. We cannot go back,” one of the family members said. “I would never allow my [family] to go back. We had to leave.”161

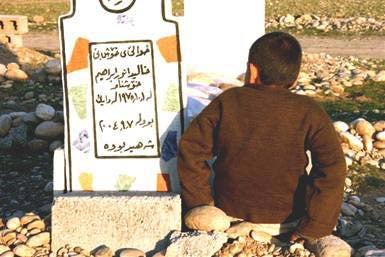

In a case with a Kurdish victim, unknown insurgents abducted and beheaded Khalid Anwar Ibrahim Mustafa Khoshnaw, a father of five, in Mosul on September 9, 2004.

A son of Khalid Khoshnaw sits by his

father’s grave outside Arbil.

Unknown insurgents abducted and beheaded Khalid,

a Kurdish father

of five, in Mosul on September 9, 2004.

© 2005 Human Rights Watch

Although he was not formally working for the U.S. government or military, he did occasionally visit the U.S. base at the Mosul airport, his family said, and he had previously worked with the CPA in Arbil.162 His precise relationship to the U.S. government remains unclear but, by all accounts, he was not engaged in hostilities and was a civilian under the law.

Armed men previously had threatened Khoshnaw, a taxi driver in Mosul who was married to an Arab woman for thirteen years, two family members said. About one month before his murder, an unknown group had abducted him for ten days, but they released him unharmed.

On September 9, Khoshnaw went out to buy breakfast with his young son in the al-Karama neighborhood. Some minutes later, the son returned alone. Two days later, Khoshnaw’s decapitated body appeared on a street with the left hand also severed. A relative explained the circumstances of the murder:

He went out to get breakfast. A bit later, about fifteen minutes, his son came home and said, “my father has been killed.” I went to the place where the car was and I saw it burning. It was near our house. The car was on fire but the fire engine was there and the police too, trying to put out the fire. I asked the police, and they told me Khalid had been taken away.

They told me nothing else. I went home, but the next day people told me his head had been found near where the car was. I didn’t go myself but neighbors went to the hospital to identify the head. The next day, his father went to the hospital and identified his son. The body was found two days later. I learned from the hospital that they had discovered the body. We have a relative who works there. Khalid’s father identified the body because of the tattoos with his children’s names [on the severed hand].163

Three-and-a-half months after his murder, Khoshnaw’s wife gave birth to a baby boy, Ghaffur.

One case reported in the press happened on January 21, 2004, when gunmen attacked a minibus carrying workers from Baghdad to the U.S. military base in al-Habbaniyya near al-Falluja. Five Christian women were killed.164 U.S. Brigadier General Mark Kimmitt believed the purpose of the attack was “to send a message of terror to those people that if you work for the coalition... we can reach out and touch you.”165

Some employees of foreign governments received threats that caused them to leave their jobs, and subsequently moved to the relative safety of the Kurdish-controlled north or fled Iraq. One such man who spoke with Human Rights Watch in northern Iraq was a car mechanic in Mosul. In the summer of 2004, he said, U.S. soldiers asked if he would work on their vehicles. He repaired two Humvee military vehicles and, one week later, was visited by Iraqi men he did not know. He explained:

One week later, two men came in dishdasha [white robes] and red scarves. I don’t know if they were armed. “Why are you working for the Americans?” they said. “If you don’t stop that, we will kill you.” I said “I’m just earning a living.” They said, “If you don’t stop, we’ll kill you.” Out of fear, I never went back to my work again. And one week later we left.166

[148] “Iraqi Militants Behead Man Who Worked With U.S. Forces in Mosul,” Associated Press, October 23, 2004, and “Al-Qaeda-linked Group Beheads Alleged ‘Spy’ in Iraq: Website,” Agence France-Presse, October 23, 2004.

[149] Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction, Report to Congress, April 30, 2005.

[150] Rick Jervis, “Intimidation, Attacks Take Toll on Contractors in Iraq,” USA Today, September 7, 2005.

[151] Sabrina Tavernise, “Iraqis Working for Americans Are in Insurgents’ Cross Hairs,” New York Times, September 18, 2004. For another article about attacks on translators, see “Iraqi Translator Defiant in Face of Death Threats Longs for Peace,” Agence France-Presse, June 25, 2004.

[152] Human Rights Watch interview with family member A, Bartala, Iraq, January 31, 2005.

[153] Human Rights Watch interview with family member B, Bartala, Iraq, January 31, 2005.

[154] Death Certificate, Iraqi Ministry of Health, #669266, August 31, 2004.

[155] Human Rights Watch interview with victim, Bartala, Iraq, January 31, 2005.

[156] Human Rights Watch interview with family member A, Bartala, Iraq, January 31, 2005.

[157] Human Rights Watch interview with family member, Zakho, Iraq, February 7, 2005.

[158] “Terrorist Attacks on Assyrians Intensify,” www.assyrianchristians.com/news_terroristattacks_june_24_04.htm (accessed February 23, 2005).

[159] Ibid.

[160] Human Rights Watch interview with a Sliwa brother, ‘Ain Kawa, Iraq, January 25, 2005.

[161] Human Rights Watch interview with Sliwa family member, ‘Ain Kaws, Iraq, January 25, 2005.

[162] Human Rights Watch interview with family member, Arbil, Iraq, January 26,2005

[163] Human Rights Watch interview with family member, Arbil, Iraq, January 27, 2005.

[164] Cecile Feuillatre, “Families Mourn Iraqi Women Slain for Doing Washing of US Troops,” Agence France-Presse, January 23, 2004.

[165] Alissa J. Rubin, “Four Iraqi Women Slain on Way to Work at Base,” Los Angeles Times, January 23, 2004.

[166] Human Rights Watch with victim, ’Ain Kawa, January 29, 2005.

| <<previous | index | next>> | October 2005 |