<<previous | index | next>>

Case Studies

Since December 2003, ENDF forces in Gambella have committed widespread human rights violations against Anuak communities throughout the region. These abuses have included large-scale attacks on villages, extrajudicial killings, rape, beatings and torture and destruction of property and looting. Some of the most egregious examples of these abuses are presented here in case studies of three Anuak communities. As documented below, the testimony gathered by Human Rights Watch evidences a similar pattern of abuse that occurred throughout Gambella in late 2003 and 2004.

Ethiopian Army Raid against Anuak Civilians in Pinyudo

Pinyudo lies roughly 110 kilometers to the south of Gambella town, close to the banks of the Gilo River. It is the largest predominantly Anuak town in Gambella. The town’s population includes a sizeable minority of highlanders but neighborhoods are largely segregated along ethnic lines.

On the afternoon of December 16 or 17, 2003, a few days after the massacre in Gambella town, Ethiopian soldiers stationed near Pinyudo conducted a raid on the town’s Anuak neighborhoods. Pinyudo’s Anuak population was already on edge because soldiers had shot and killed a young man named Akurkwar Bok Olay several days earlier in the center of town and refused to offer any explanation for the killing.58 However, word of the violence in Gambella town had not yet reached Pinyudo and the attack caught most people completely by surprise.59

It is not clear how the attack in Pinyudo began. Some witnesses later heard that there had been a clash between military forces and a group of armed Anuak just outside of the town at around the time the violence erupted. However it started, the attack quickly evolved into a destructive assault on Pinyudo’s Anuak neighborhoods. Witnesses report that panic gripped the town’s Anuak population as soldiers moved into Anuak neighborhoods, deliberately setting fire to houses and firing at fleeing Anuak residents. Hundreds of families fled as the soldiers descended on their homes, most of them in the direction of the Gilo River. As the smoke from burning houses filled the air above the town, many of the fleeing persons swam across the river to hide in the tall, dense grass that lay beyond the opposite bank.60

The vast majority of the people who fled managed to escape safely into the bush. A small number of people sought refuge in their homes or in the houses of neighbors instead of fleeing, however; at least two of them were reportedly burned alive inside their homes.61 One thirty-two-year-old man who was hiding in the house of a friend described seeing soldiers loot and burn all of the houses around him, including his own. He then watched as a friend of his ran out from a neighboring house after soldiers set fire to its grass roof; a soldier shot and killed him before he had managed to make it more than a few meters from the door.62

Late in the day, the violence subsided. Wereda63 officials arrived on the scene and began moving along the banks of the Gilo River with loudspeakers, announcing that the situation had been brought under control and urging people to return to their homes.64 Many people were skeptical and remained hidden, but a large group of people emerged from the grass and began making their way back across the river. As they stepped into the water, soldiers on the opposite bank opened fire indiscriminately. One sixty-year-old man whose two sons were cut down in the water described watching them die:

They were moving along the bank calling, “Come back, there is peace now.” [My sons] were in a hurry to go back and see their homes. When they came crossing the river they were killed. I saw them fall….I saw the [members of the] defense forces who shot them. I immediately recognized them when they had fallen and I ran to them. After the death of these people and my two sons, the people still on the bank ran away to the forest. I had nothing to do—I had already died. When the people ran away I stayed behind….

According to my culture, the first person to die should be the old person. But these were my two sons.65

Human Rights Watch was able to document twelve killings of Anuak residents by soldiers in Pinyudo town during the course of the day; the actual total may be higher.

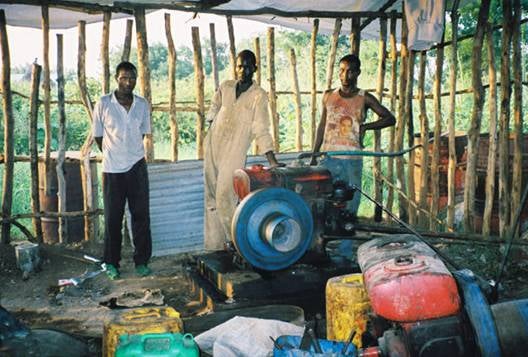

Soldiers also looted at least one clinic and ransacked a junior secondary school.66 The attackers also disabled a community grinding mill that had been operated collectively by Anuak households; it had not been repaired at the time of Human Rights Watch’s visit to the town.67

ENDF soldiers deliberately disabled this grinding mill during the attack

in Pinyudo.

The townspeople who once made use of it had not been able to

repair it at the time of Human Rights Watch’s visit.

© 2004 Human Rights Watch

By the close of the day, the violence came to an end, and over the next few days many people began returning home. Most found that they had been left homeless; nearly every house in the most densely populated Anuak neighborhoods had been razed and many had been looted. Well-informed regional officials speaking on condition of anonymity estimated that well over 1000 homes were destroyed in total.68 The officer then in command of military forces in the area around Pinyudo, Captain Amare, initially claimed to regional officials sent to investigate the destruction that only a handful of houses were destroyed. He later admitted that a large number of homes were burned but said that all of them were destroyed accidentally in the course of his soldiers’ efforts to fend off an attack by Anuak shifta.69 As most of the grass around Pinyudo town had already been cleared by ENDF soldiers, there was not enough available to build roofs for reconstructed houses. As a result, hundreds of families spent months living under makeshift shelters covered with plastic sheeting.

Ethiopian Army Raids against Anuak Villages in Tedo Kebele

Tedo is a rural kebele70 in the Jor region of Gilo wereda that encompasses several remote Anuak villages. Three of the kebele’s villages were attacked by ENDF forces over the course of roughly three weeks beginning in March 2004. In each of three surprise raids, villagers were forced to flee into the forest as soldiers burned and looted their homes behind them. At least seventeen Anuak civilians were killed in total.71

The first of the three attacks took place in a village called Bad Kut. In the mid-afternoon, a large group of soldiers descended upon the village, catching its population completely off guard. One witness described the first moments of the attack and its aftermath in some detail:

I was there when they arrived. People were just sitting and the women were preparing food. The men, we were just sitting and talking. We didn’t see them right when they came—we heard guns shooting and when we looked we saw that it was soldiers who were shooting. After the shooting we had to think of running and so we didn’t see what they did. But after we escaped we could see houses burning and the whole village on fire. When we went back we saw burned houses and our things were broken. Cattle and property were taken and goats and sheep were killed. Also the pots we use to store grain and powdered maize were broken. Even the shells we use to eat food were broken….My house was there and it was burnt down….Bad Kut was fifty houses—it is one of the bigger villages in Tedo. Almost all of the houses were burnt down. Only a few remained.72

Other witnesses gave similar accounts to Human Rights Watch. In addition to looting and burning at least several dozen homes and destroying grain stores, the attackers reportedly looted the village’s primary school and stole the tin roofing from the church. Between five and eleven people who did not manage to escape were shot and killed as the soldiers entered the village.73

The second attack took place one to two weeks later in the village of Cham, a small village roughly three hours on foot from Bad Kut. Villagers there said that they had been nervous since hearing news of the attack on Bad Kut, but the attack on Cham nevertheless also caught them by surprise. According to some witnesses this was because the attacking soldiers approached from an unexpected direction that allowed them to conceal their approach. As in Bad Kut, the villagers fled as the soldiers drew near the village. At least five people were shot from behind and killed as they ran. The remaining villagers fled into the forest and returned several hours later to find many of their homes destroyed and most of their possessions looted. One survivor of the attack recalled:

Our houses and all of the grain stores were burned. All of the cooking pots and dishes were destroyed. They took all of the cattle and sheep and goats. We saw this when we returned. Almost all the village was burned down; it was only this village that was attacked. My house was burned. They looted everything.74

One to two weeks after the attack on Cham, the military conducted a raid on the nearby village of Abunjay. The soldiers entered the village in the early hours of the morning, and again succeeded in catching the population by surprise. One witness recounted what took place:

There was a little bit of rain. As the rain stopped early in the morning they came and started shooting at people. The people escaped and ran away. I ran also. When we were running they were chasing us….They burned down the whole village and they took everything. They destroyed everything like cattle, sheep, goats, grain stores and the powdered maize in big jars. Two old women were burned in their houses. I saw their bodies in the houses after we returned. We could only recognize them by their homes—you could not even tell who they were.75

At least seven Anuak residents were killed in the attack.

Anuak villagers from these three villages told Human Rights Watch that after the third attack many people in Tedo left their homes and crossed into southern Sudan as refugees. One man from Abunjay said that after the attack on his village, “all of the villagers went to Pochalla and there was no more life in Tedo.”76

Witnesses to the attacks in Tedo kebele were at a loss in trying to explain them but believed that their substantial herds of cattle, sheep and goats may have been one motivating factor. In all three villages, the attacking soldiers rounded up and stole entire herds of livestock. Several months after these attacks, Human Rights Watch researchers observed several dozen cattle that had been taken from villages in Tedo grazing outside of Pinyudo town, watched over by a young soldier. Soldiers reportedly sold some of the stolen cattle to buyers in town and used the remainder to supplement their diet.77

There have been no reported raids on villages in Tedo kebele since March 2004, but ENDF soldiers continue to commit abuses against the local population. In two separate incidents in May, women walking alone along the road were caught and gang-raped by soldiers in ENDF patrols.78 In a third and especially gruesome reported incident, a group of soldiers captured a group of six women and two men who were walking together in the countryside. The soldiers cut the throats of the two men, Okwier Omot and Manyu Chan, while the women watched and then raped all six of them.79

Ethiopian Army Abuses against Anuak Civilians in Gok

Gok Jinjor and Gok Dipatch are kebeles within Gilo wereda. The population of both kebeles is overwhelmingly Anuak. The Ethiopian military has committed human rights abuses against Anuak civilians living throughout this area over the course of the past year. Since the establishment of a permanent military camp in Gok Dipatch in July or August 2004, however, these abuses have grown considerably more frequent and serious.

Prior to the stationing of a permanent military garrison in Gok Dipatch, military patrols were frequently sent to Gok from the garrison near Pinyudo to search for shifta and illegal weapons. Soldiers frequently detained and beat any Anuak men they came across in their patrols and occasionally looted Anuak villages.80 ENDF soldiers also raped some Anuak women who they caught alone outside of their villages.81

In July or August 2004, the military established a permanent camp in Gok Dipatch. Several individuals from villages in Gok told Human Rights Watch that their problems with ENDF soldiers had grown much worse since then. One man who had recently fled a patrol approaching his village and spent that night in the forest said that since the arrival of this garrison, “things have become very serious. There is lots of raping and if you accidentally meet them on your way to another village they will beat you. So people are always ready—your clothes are always in a bag and ready for running.”82

Patrols from the camp move between all of the Anuak villages in Gok Dipatch and Gok Jinjor kebeles. These patrols conduct frequent searches of Anuak houses, often destroying or looting property in the process. One man from a village near Gok Dipatch reported to Human Rights Watch that a patrol had come to his village, accused the people there of hiding bullets in the jars of powdered maize the community had stored from their last harvest, and poured all of it out into the dirt.83 Several villagers from Gok Dipatch said that the soldiers seemed especially fond of the honey many households gather to supplement their diet and would steal it whenever they come across it while searching a house for weapons. As one local man said, “Because everything is in their hands, they take whatever they want.”84

At least ten Anuak civilians have been shot and killed by ENDF soldiers from the Gok Dipatch garrison since December 2003. Many of those were killed while attempting to flee a group of approaching soldiers. The most notorious of the killings in Gok was the murder of Oballa Obang,85 an elderly and widely respected village chairman from Gok Jinjor who had been an active community leader since the days of Haile Selassie, Ethiopia’s last emperor. The commander of the military garrison in Gok Dipatch had called a meeting of community leaders in Gok Jinjor; the main purpose of this meeting was to demand that Oballa respond to accusations that he had been furnishing food and other material support to Anuak shifta. Oballa sent a message saying that he was sick and did not attend the meeting. After the meeting adjourned, a group of soldiers went to his house. According to witnesses, they told him that they did not believe he was actually ill and arrested him. Oballa was then taken to the campus of a nearby school, which the ENDF garrison was using as its headquarters. According to one eyewitness, the soldiers present began threatening to kill Oballa. He became frightened and tried to run away; two or more soldiers shot him in the back and he died almost instantly. The next day, villagers followed a trail of blood to find his body buried in a shallow grave in the forest not far from the school.86

Human Rights Watch interviewed several villagers from communities near the Gok Dipatch garrison, and all of them said that women from their villages had been raped by soldiers stationed there. Some of them were raped on the roads; in other cases soldiers have followed women who venture outside of the village to fetch water and attacked them there. One man from a village in Gok Dipatch kebele called Che Aba described what happened to one of his relatives:

She was trying to go and fetch water at night; there were some soldiers guarding the way. They asked her her name and she told them. They said, “Where are you going?” She said she was getting water. He asked her, “Why are you going at night?” She said, “I want to get some water for tomorrow morning.” Then she left, but one of the soldiers followed her. After she fetched the water and was trying to go back he took the jerrican from her and did not want her to go. She cried out, but no one went to see what had happened. He then forced her. She left everything there, even the jerrican, and came home. When she came back she told us this thing.87

Officers from the Gok Dipatch garrison regularly require villagers to attend meetings, but they are not responsive when those present raise complaints about the soldiers’ behavior. One man from a village close to the garrison said:

They have many meetings. They surround the village and say, “We want to meet with you….” In these meetings they say, “Now we have to talk about peace and how peace will come.” People respond, “But we had peace when you were not here.” All these months we are always having meetings with them, but they are not meetings for something to happen. They are just for confusing people. [We] tell them the same things in all the meetings but nothing comes of it. We are fed up with all of these meetings. 88

In one meeting a village chairman demanded that the officers in command of the garrison do something to stop soldiers from raping women from his village:

The chairman raised these issues with the military at this meeting. At this meeting the military was mainly discussing how to bring about peace. They said that they were there for the peace and security of the villagers. The chairman said, “No, your being here is a problem. You are not living in peace, you are raping women”—he was even mentioning their names—“and beating people in the villages.” They were just telling him that what he said is something which could be wrong or not correct. They said, “You have to tell us the names of the soldiers who raped these women.” But [the soldiers] all look the same.89

In another incident, a woman from a village near the Gok Dipatch garrison was attacked and raped by four soldiers in the early hours of the evening. She screamed, several people from the village came running to see what was happening, and the soldiers fled. The next day, community leaders went to the garrison to report the incident and were told that it would be investigated. Villagers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that a short while later, a letter from the garrison’s commanding officer arrived in the village. The letter said that since the soldiers in the garrison were difficult to control, the best way for the community to avoid problems in the future would be to make sure that women did not leave the village unaccompanied. The soldiers responsible for the rape that had been reported were never punished.90

[58] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #33, 44, 72, 73 and 74, Gambella, late 2004.

[59] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #43 and 74, Gambella, late 2004.

[60] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #3, 26, 33, 35, 51 and 72, Gambella and Ruiru, Kenya, late 2004.

[61] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #7, Gambella, late 2004.

[62] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #43, Gambella, late 2004.

[63] A wereda is a unit of administrative governance in Ethiopia. The country’s nine regions are divided into zones, and the zones are divided into weredas. Gambella is divided into six weredas and one ‘special’ (or autonomous): Gambella, Alwero-Openo, Gilo, Jikaw, Akobo, Dimma and Godere (special).

[64] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #3, 33, 34, 47, Gambella and Ruiru, Kenya, late 2004.

[65] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #47, Gambella, late 2004.

[66] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #31, 48 and 57, Gambella, late 2004.

[67] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #48 and 57, Gambella, late 2004.

[68] Human Rights Watch interview with federal government official, Addis Ababa, late 2004; Human Rights Watch interview with regional government official, Gambella, late 2004.

[69] Human Rights Watch interview with regional government official, Gambella, late 2004.

[70] A kebele is the unit of administrative governance below a wereda and the smallest unit of government in Ethiopia. In urban areas, kebeles are akin to neighborhood associations while in rural areas they often encompass several small villages and hamlets over a relatively large area.

[71] This is a conservative estimate and likely understates the number of people killed.

[72] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #54, Gambella, late 2004.

[73] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #44, 51, 54 and 71, Gambella, late 2004.

[74] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #51, Gambella, late 2004.

[75] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #71, Gambella, late 2004.

[76] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #44, Gambella, late 2004. Many of the villagers who fled have subsequently returned and there have been no reported attacks on villages in Tedo kebele since the attack in Abunjay.

[77] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #51, 54 and 71, Gambella, late 2004.

[78] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #71, Gambella, late 2004.

[79] Ibid.

[80] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #17, 39 and 61, Gambella, late 2004.

[81] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #53, 58 and 84, Gambella, late 2004.

[82] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #53, Gambella, late 2004.

[83] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #76, Gambella, late 2004.

[84] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #58, Gambella, late 2004.

[85] Oballa Obang was known to many as Oballa Gach

[86] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #31 and 79, Gambella, late 2004.

[87] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #42, Gambella, late 2004.

[88] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #53, Gambella, late 2004.

[89] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #78, Gambella, late 2004.

[90] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #58 and 76, Gambella, late 2004.

| <<previous | index | next>> | March 2005 |