<<previous | index | next>>

Notes on Wahhabism, “Wahhabis,” and Hizb ut-Tahrir

Wahhabism and “Wahhabis”

In Central Asia, government leaders and government-aligned clergy use the term “Wahhabism” to denote “Islamic fundamentalism” and “extremism.” It is often used as a slur, with strong political implications.89 There is a common misconception, encouraged by the government of Uzbekistan, that within Islam there are three schools: Sunni, Shi’a, and Wahhabi. In fact, Wahhabism, a revivalist movement that grew out of the Hanbali school, is a branch of Sunni Islam practiced in Saudi Arabia and elsewhere. The name derives from its eighteenth century founder, the Hanbali teacher and reformer Muhammad ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhab (1703-1792).

Wahhabism advocates a purification of Islam, rejects Islamic theology and philosophy developed after the death of the Prophet Muhammad, and calls for strict adherence to the letter of the Koran and hadith [the recorded sayings and practices of the Prophet]. In promoting what its adherents view as the precepts of early Islam, Wahhabism maintains a strict and puritanical view of religious rites. It eschews "innovations," including practices viewed as polytheistic, such as the worship of saints, mysticism, and decoration of graves. It prohibits dancing and music.

Ibn Wahhab came under the protection of Muhammad ibn Saud and the alliance of the Wahhabi movement and the Saud family, now the rulers of Saudi Arabia, remains formidable to this day. A small number of Sunni Muslims in Uzbekistan are in fact followers of Saudi-style Islam and therefore could be called Wahhabi. They adhere more strictly than adherents of other schools of Sunni Islam to the letter of the Koran and hadith, to the exclusion of other sources.90

Views differ as to when Wahhabism first found adherents in Central Asia. Pakistani journalist and author Ahmed Rashid estimates that this occurred in 1912, but that Wahhabism failed to gain much popularity.91 Haghayeghi argues that Wahhabi principles may have spread from India to Central Asia in the early part of the 1800s.92

Haghayeghi draws clear distinction between the Hanafi school and the Wahhabi movement. The Hanafi school of Sunni Islam is another one of the four main schools of law and distinct from the Hanbali school. Haghayeghi writes that adherents emphasize analogy, critical scrutiny, public consensus, and private opinion when implementing and interpreting Islamic principles.93 The Hanafis’ tolerance and even reverence for difference of opinion, according to Haghayeghi “…places the Hanafi school farthest away from the conservative or dogmatic understandings of Islam.”94

Haghayeghi notes that Wahhabism had little resonance with the population of Central Asia because of that branch’s “puritanical views” and rejection of private opinion and public consensus.95 Rashid points to the dramatic difference between actual Wahhabis and the so-called Wahhabis targeted by the Uzbek government:

In 1992[…] the Uzbek government began to label anyone who was perceived to be an adherent of radical Islam or held anti-government sentiments as part of his Islamic beliefs, a Wahhabi. By 1997 the government was labeling as Wahhabis even ordinary Muslims who practiced Islam in unofficial mosques or engaged in private prayer or study. Any Muslim who associated with unregistered prayer leaders or taught children how to read the Koran was also termed a Wahhabi. Today the government uses Wahhabi to undermine all Muslim believers by associating them with the Wahhabis’ record of extremism. Such mislabeling, whilst demonstrating the lack of real knowledge about Islam amongst the ruling elites, enables them to suppress all Islamic activity merely by naming it Wahhabi.96

Indeed the vast majority of those branded by the Uzbek government as “Wahhabis” had little in common with the relatively small group that actually follow Wahhabi doctrine. Notably, they were almost without exception adherents of the Hanafi school. Independent Muslims who were followers of the Hanafi school were not necessarily in favor of the establishment of an Islamic state, or application of shari’a in Uzbekistan. Consistent with Hanafi principles, many were believers, but were not all strictly observant practitioners. They often continued to observe pre-Islamic, namely Zoroastrian, rituals.97 Qualification as a “genuine” Muslim, then, has been for them more dependent on submission to God and his Prophet Muhammad than participation in rituals and strict adherence to duties.98 Religious rules regulating marriage, divorce, funerals, and other ceremonies differed dramatically from those followed by Wahhabis.

Many independent Muslims in Uzbekistan objected to the politicization of religion both by Wahhabis and by the government. Many so-called moderate Muslims were branded “extremists” and, ironically, “Wahhabis” for repudiating the government’s injection of politics into sermons and rituals. Under President Karimov, a person who moved beyond the official, limited definition of religious observance—by studying Arabic in order to read the Koran in its original language, sticking strictly to the observance of the five daily prayers, or appearing in public dressed in a way that suggested piety—was considered deviant or “Wahhabi.” People have also been called “Wahhabi” for showing respect for or declaring allegiance to any authority not sponsored by or directly associated with the state structure—this was viewed by the Karimov government as an affront to its power, a danger to be curbed. Thus, visits to the homes of local religious teachers, attendance at mosques not registered with the state, and most importantly the placement of loyalty to Islam before loyalty to political leaders, were regarded by the state apparatus as displays of excessive independence. Refusals by imams and others to serve as informants for the state security agents regarding the activities and beliefs of their coreligionists was similarly seen as unacceptable insolence.

Hizb ut-Tahrir

Hizb ut-Tahrir members form a distinct segment of the independent Muslim population by virtue of their affiliation with a separate and defined Islamic group with its own principles, structure, activities, and religious texts.

Hizb ut-Tahrir is an international Islamic organization with branches in many parts of the world, including the Middle East and Europe. Hizb ut-Tahrir propagates a particular vision of an Islamic state. Its aims are restoration of the Caliphate, or Islamic rule, in Central Asia and other traditionally Muslim lands, and the practice of Islamic piety, as the group interprets it, (e.g., praying five times daily, shunning alcohol and tobacco, and, for women, wearing clothing that covers the body and sometimes the face). Hizb ut-Tahrir renounces violence as a means to achieve reestablishment of the Caliphate. However, it does not reject the use of violence during armed conflicts already under way and in which the group regards Muslims as struggling against oppressors, such as Palestinian violence against Israeli occupation. Its literature denounces secularism and Western-style democracy. Its anti-Semitic and anti-Israel99 statements have led the government of Germany to ban it.100 The government of Russia has also banned the group, classifying it as a terrorist organization.101

Some in the diplomatic community, in particular the U.S. government, consider Hizb ut-Tahrir to be a political organization and therefore argue that imprisoned Hizb ut-Tahrir members are not victims of religious persecution.102 But religion and politics are inseparable in Hizb ut-Tahrir’s ideology and activities, and one of the chief reasons Uzbek authorities arrest members is the religious ideas Hizb ut-Tahrir promotes: the reestablishment of the Caliphate and strict observance of the Koran. Even if one accepts that there is a political component to Hizb ut-Tahrir’s ideology, methods, and goals, this does not vitiate the right of that group’s members to be protected from religion-based persecution.

Hizb ut-Tahrir in Uzbekistan

Hizb ut-Tahrir is not registered in Uzbekistan and is therefore illegal. It is referred to as a “banned” organization, though in contrast to the means used by German authorities to ban Hizb ut-Tahrir, no single Uzbek administrative or judicial decision has ever prohibited the organization.103

Members meet in small groups of about five people, referred to as “study groups” by members and as “secret cells” by Uzbek government officials. Both sides acknowledge that the primary activity of these small groups is the teaching and study of Hizb ut-Tahrir literature, as well as traditional Islamic texts such as the Koran and hadith. Membership in the group is solidified by taking an oath, the content of which has been given variously as: being faithful to Islam; being faithful to Hizb ut-Tahrir and its rules; and spreading the words of the Prophet and sharing one’s knowledge of Islam with others.104 Law enforcement and judicial authorities generally considered both those who had and had not taken the oath as full-fledged members.

In Human Rights Watch interviews and in court testimony, Hizb ut-Tahrir members have overwhelmingly cited an interest in acquiring deeper knowledge of the tenets of Islam as their motivation for joining the group. Hizb ut-Tahrir members in Uzbekistan, and likely elsewhere, regard the reemergence of the Caliphate as a practical goal, to be achieved through proselytism.

Members in Uzbekistan distribute literature or leaflets produced by the organization which include quotations from the Koran, calls for observance of the basic tenets of Islam, and analysis of world events affecting Muslims, including denunciation of the mass arrest of independent Muslims in Uzbekistan.

Peaceful or Violent?

Hizb ut-Tahrir’s designation as a nonviolent organization has been contested. Hizb ut-Tahrir literature does not renounce violence in armed struggles already under way—in Israel and the Occupied Territories, Chechnya, and Kashmir—in which it views Muslims as the victims of persecution. But Hizb ut-Tahrir members have consistently rejected the use of violence to achieve the aim of reestablishing the Caliphate, which they believe will only be legitimate if created the same way they believe the Prophet Muhammad created the original Caliphate, and which can occur only as a result of gradual “awakening” among Muslims.

Human Rights Watch is not aware of Hizb ut-Tahrir members in Uzbekistan charged with undertaking an act of violence.105 An anonymous leader of Hizb ut-Tahrir reportedly told Ahmed Rashid that “Hizb ut-Tahrir wants a peaceful jihad [struggle] that will be spread by explanation and conversion, not by war.”106 Members of the group in Uzbekistan have uniformly renounced violence and asserted their commitment to peaceful advocacy of Muslim practice and adherence to the goal of a Caliphate. Hizb ut-Tahrir literature states that only God is empowered to determine when the Caliphate will actually come to be. Members also vigorously profess their abhorrence of violence and their belief that the use of violence, particularly murder, is a sin according to Islam.

One young member of Hizb ut-Tahrir told Human Rights Watch, “There will not be a jihad, we will not turn to violence. We will spread the ideas of Hizb ut-Tahrir, but we will not fight.”107 When asked by a judge to name the actions Hizb ut-Tahrir planned to take to realize its goal of an Islamic state, accused member Shahmaksud Shobobaev said that the group’s principles were consistent with the teachings of the Koran and that, “Hizb ut-Tahrir condemns terrorism, any use of weapons, to establish an Islamic state. When peoples’ consciousness changes, when they are pious and want to do good things, the Hizb ut-Tahrir idea is to establish a real, good state.”108 When Judge Rakhmonov later asked Shobobaev whether or not he would kill for Allah at the direction of Hizb ut-Tahrir, the defendant responded, “No. No one would ask such a direct, stupid question… We are not going to kill anybody. We are not reactionaries, we are just expressing our views.” He added, “Our idea was to teach, not to use force.”109 When a lay assessor asked Shobobaev’s co-defendant, Tolkhon Riksiev, “How can you change the country without [using] weapons?” the accused man answered, “We don’t discuss establishing the Caliphate now. We just call people [proselytize] and believe they will decide for themselves how to live.”110 When the lay assessor challenged him, saying that this could take centuries, Riksiev stated, “Allah calls us to be patient.”111

Judge Rakhmonov noted that Riksiev’s co-defendant Aflotun Normukhamedov had expressed dissatisfaction with the current government system in Uzbekistan and embraced a Caliphate as a better system, but acknowledged also, “He does not recognize the use of force or weapons. He only wanted to peacefully establish a Caliphate.”112

Hizb ut-Tahrir’s Religion and Politics

Hizb ut-Tahrir’s goals are a mix of religion and politics. According to a statement by the leadership of the international group, “Hizb ut-Tahrir is a political party whose ideology is Islam, so politics is its work and Islam is its ideology.”113 The statement explained, “...politics in Islam is looking after the affairs of the people, either in opinion or in execution or both, according to the laws and solutions of Islam.”114 That is, Islamic politics is the explanation and implementation of Islamic law, shari’a. Hizb ut-Tahrir also claims that the idea of the Caliphate is consistent with Hanafism, and indeed is the truest expression of the teachings of Hanafism’s founder.115

Many people have been imprisoned for possessing or distributing Hizb ut-Tahrir literature. The political content and consequences of this literature has led some observers, particularly members of the diplomatic community, to regard the literature and the activity of disseminating the literature as primarily political and not religious in nature. The U.S. in particular views the group as political and overlooks the religious ideas and goals its literature contains. To be sure, Hizb ut-Tahrir literature opines on such political phenomena as the repressive policies of the Uzbek government, the arrest and torture of Hizb ut-Tahrir members, corruption in Uzbekistan, and the armed conflicts in Israel and the Occupied Territories, Kashmir, and Chechnya. But it also expounds the duty, which members believe was prescribed by the Prophet Muhammad, for Muslims to reestablish the Caliphate, and reiterates the need to convince others to become observant Muslims. Dissemination of these ideas is considered part of a program of religious proselytism.116

Islam as a Complete and Comprehensive System

Members of Hizb ut-Tahrir, like many other Muslims, believe that Islam is a complete system, incorporating rules for all kinds of human conduct, including the direction of politics, economics, family relations, etc. Members’ political activities, which consist of propagation of the ideas of Hizb ut-Tahrir, are subservient to the organizing ideology in which they take place, and which they promote—Islam. Politics is viewed as part of a religious doctrine, the implementation or realization of religious belief.117

This idea was expressed by Hizb ut-Tahrir member Shahmaksud Shobobaev, who testified that as part of the group he had engaged in Islamic education and the spread of religious ideas. When the Tashkent City Court judge asked Shobobaev whether or not he had been “involved in politics,” he responded, “Religion has politics and finance in it, everything. I just wanted people to be religious.”118 He added, “I have nothing against the existing state.”119

Hizb ut-Tahrir also claims that Islam is a superior religion because it contains a comprehensive system of beliefs and governance120 and because it is a religion revealed by God.121

Opposition to Secularism and Democracy

As explained above, Hizb ut-Tahrir rejects the separation of religion and politics,122 and so also rejects “Western” secularism. An April 2000 leaflet states:

It is well known that Western laws derived from the doctrine of separation of religion from life and state are applied all over the world, including the Islamic world, with Uzbekistan being part of it. It was well known ahead of time that this doctrine, being false, could not stand [up against] the truth, i.e. Islam, and guarantee justice in the world by separating religion from the life. That is why today, when Islam together with the Islamic community regains its lost stature, this infamous faith [separation of religion and state] cannot withstand this process and retreats from its own laws, thus showing the rotten decline of its era… Undoubtably [sic], this fallacious doctrine of separation of religion from the life, state, and politics and, derived from it, the western ideology and legislation has corrupted the whole world. Therefore, the western ideology and laws, its states coupled with its menial servants in the Islamic countries, absolutely do not have any right to govern mankind. In the meantime, Islam by means of [rational thought] and clear documentation has proved the ineligibility of all other religions, doctrines, ideologies and systems.”123

This rejection of secularism and Hizb ut-Tahrir’s view of Islam as a superior social, political, and economic system are at the heart of its stance against democracy.

Anti-Americanism

Hizb ut-Tahrir leaflets often portray President Karimov as a proxy of undefined global forces, led by the U.S. government, that seek to impose “alien” western ideas on the people of Uzbekistan.124

The U.S. government is seen as the driving force behind Uzbekistan’s drive to preserve secularism: “…The USA, watching the unprecedented spread of Islam in Central Asia, specifically the movements to renew the Islamic life and reestablish the Khilafah State, and wishing to prevent them from spreading, ordered their servant Karimov to create a basis and ideology for the state of Uzbekistan other than Islam.”125

Hizb ut-Tahrir portrays U.S.-led counter-terrorism actions as an assault on Islam and a transparent attempt to assert cultural hegemony. An April 2000 leaflet, for example, reads:

America had noticed that Islam was spreading in Central Asia. Thus she feared for her influence and ambitions there. She feared for her culture and herself due to the rise of Islam, which she saw not as a mercy to her but as an affliction on her. That is why she and all the Kufr [unbeliever] states call it terrorism and are holding conferences and draw up plans to fight it.126

Anti-Semitism

Hostility to Jews is a recurring theme in Hizb ut-Tahrir literature. This is frequently expressed in denunciations of President Karimov as a Jew or kafir (unbeliever).

Hizb ut-Tahrir blames Karimov’s campaign against the group on his alleged Jewish identity. Commenting on an unfair trial that resulted in twenty-year prison sentences for ten members of Hizb ut-Tahrir, an April 9, 2000 leaflet stated:

…though the prosecutors, having ‘proved’ trumped-up charges against Members of Hizb ut-Tahrir, which carries an ideological and political call to Islam, asked the judges for [varied] terms, they (the judges) disregarded the request and sentenced all of [the defendants] to 20 years of imprisonment. This is due to the fact that today the Uzbekistan regime led by the Jewish unbeliever Islam Karimov holds trials of Members of Hizb ut-Tahrir, basing its decisions not on the laws in force, but on fear and hatred of Islam… Playing about with ideas like ‘legal state’ and ‘justice,’ the Uzbekistan regime shows the people of this country, via such unjust rulings in its court cases, how [tyrannical] and deceitful it is. Moreover, the ‘state,’ claiming to be legitimate[ly]…led by the Jewish disbeliever Karimov, by all means shows its full ignorance of its own laws in force.127

After describing authorities’ systematic arrest and torture of Hizb ut-Tahrir members and other Muslims, another leaflet states, “This harshness of Karimov comes from his origins as a disbelieving Jew. The Jews are the most severest [sic] of people in enmity to Islam and the Muslims.”128

The man interviewed by Ahmed Rashid who claimed to be a leader of Hizb ut-Tahrir, and who was presumably located outside of Uzbekistan, stated point-blank, “We are very much opposed to the Jews and Israel. We don’t want to kill Jews, but they must leave Central Asia.”129

The Legal Setting

The Uzbek government’s campaign against independent Muslims violates the basic rights to freedom of conscience and religion and freedom of expression, which are guaranteed under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). This section first elaborates on key aspects of these rights, drawing on authoritative commentary by the U.N. Human Rights Committee, the body that monitors compliance with the ICCPR, as they relate to the situation in Uzbekistan. The second part of this section describes the abusive restrictions Uzbek law places on freedom of conscience and religion and freedom of expression.

In pressing forth with this campaign, the government violates many other obligations under international law. Not only does the government fail to protect and promote freedom of conscience and religion and freedom of expression, but its attacks on people exercising these rights also involves violations of due process and the right to liberty. Law enforcement and security agents engage in illegal searches and arbitrary arrest and detention. Once in custody, detainees are routinely tortured in violation of the ICCPR and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. The government denies independent Muslim detainees access to counsel and violates their right to a fair trial as guaranteed in the ICCPR. Even after the defendants are convicted and sentenced to prison terms, many continue to be tortured and subjected to other forms of inhuman and degrading treatment. Many aspects of prison conditions in which independent Muslim prisoners serve out their sentences violate U.N. Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners. More detailed reference is made to these instruments in the relevant chapters of this book.

Freedom of Religion in International Law

In 1995 the Republic of Uzbekistan, under the leadership of President Karimov, voluntarily acceded to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Uzbekistan ratified the ICCPR the next year, in 1996. Article 18 of the ICCPR upholds individuals’ rights to hold and to manifest their religious beliefs. It states:

Everyone shall have the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion. This right shall include freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief of his choice, and freedom, either individually or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in worship, observance, practice and teaching. No one shall be subject to coercion which would impair his freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief of his choice.

Also relevant in the context of this report is the ICCPR’s article 19, which protects freedom of expression. Article 19 states:

Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference. Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.

Articles 18 and 19 allow states to place certain restrictions on the manifestation of religion and on the exchange of information, respectively. With regard to freedom of conscience, article 18 allows only those limitations on the manifestation of beliefs that are “prescribed by law and are necessary to protect public safety, order, health or morals or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others.”130 Similarly, with regard to the right to exchange information and ideas, article 19 permits only those restrictions that are provided by law and are necessary: for respect of the rights or reputations of others; for the protection of national security, or of public order or of public health or morals.

In its General Comments on articles 18 and 19 of the ICCPR, the United Nations Human Rights Committee clarified the scope of religious belief, practice, and expression covered by this instrument. The General Comment to article 18 specifies that freedom of thought, including freedom of conscience and religious conviction, is a right that cannot be limited. In its General Comment 10 on article 19, the committee stated that there could be “no exception or restriction” on the right to “hold opinions without interference.” In recognizing the right of state parties to limit the right to free expression, the General Comment reiterates the need for such restrictions to fulfill all of the criteria set forth in the article. Moreover, it emphasizes that such restrictions “may not put in jeopardy the right itself.”131

In its explanation of the right to hold beliefs without interference, the committee notes that the ICCPR’s article 18.2, along with article 17 (stipulating the right to privacy), create a freedom from compulsion to reveal one’s thoughts or adherence to a religion or belief.132 The committee has also detailed particular manifestations of religious beliefs that should be considered protected under article 18. Section four of the General Comment states:

The freedom to manifest religion or belief in worship, observance, practice and teaching encompasses a broad range of acts. The concept of worship extends to ritual and ceremonial acts giving direct expression to belief, as well as various practices integral to such acts, including the building of places of worship, the use of ritual formulae and objects, the display of symbols, and the observance of holidays and days of rest. The observance and practice of religion or belief may include not only ceremonial acts but also such customs as the observance of dietary regulations, the wearing of distinctive clothing or head coverings, participation in rituals associated with certain stages of life, and the use of a particular language customarily spoken by a group. In addition, the practice and teaching of religion or belief includes acts integral to the conduct by religious groups of their basic affairs, such as the freedom to choose their religious leaders, priests and teachers, the freedom to establish seminaries or religious schools and the freedom to prepare and distribute religious texts or publications.133

The ICCPR bans coercing an individual to recant his or her religion or belief.134 The committee commented specifically on the rights of prisoners—who are particularly susceptible to such coercion—not only to hold, but to manifest their religious belief. It stated that, “Persons already subject to certain legitimate restraints, such as prisoners, continue to enjoy their rights to manifest their religion or belief to the fullest extent compatible with the specific nature of the constraint.”135

Finally, the committee acknowledges that states parties may adopt a state religion or ideology, and clarifies the right not to adhere to it:

If a set of beliefs is treated as official ideology in constitutions, statutes…or in actual practice, this shall not result in any impairment of the freedoms under article 18 or any other rights recognized under the Covenant nor in any discrimination against persons who do not accept the official ideology or who oppose it.136

Uzbek law violates many of the standards protecting freedom of conscience and freedom of expression. It limits or outright bans several of these manifestations of religious belief, including worship, building houses of worship, religious dress, religious teaching, the freedom to choose religious teachers and schools, and the freedom to publish and distribute religious texts. These limitations are described in more detail below. Even where domestic law conforms to international standards, Uzbek government practice violates them in ways documented throughout the report.

The Domestic Legal Context

Beginning in late 1997 the government began arresting suspected members of Islamic religious groups, closing mosques, and carrying out other restrictions in the absence of a legal framework authorizing such measures. In May 1998 Uzbek lawmakers adopted such a law, the Law on Freedom of Conscience and Religious Organizations (hereinafter, the 1998 law).137

Also in May 1998 the Oliy Majlis (parliament) adopted a series of amendments to the country’s criminal and administrative codes, providing for harsh punishments for violating the 1998 law and for other religion-based infractions.138 In May 1999 both codes were again amended to impose even stricter penalties on crimes related to religious belief and association.

Key provisions of the 1998 law that were applied against independent Muslims set out restrictions on internationally protected rights to hold and manifest religious beliefs, to freedom of association and assembly, and to freedom of expression, including the right to receive and impart information. Under international law governments may impose reasonable restrictions on rights for the purpose of regulating a legitimate state interest, but not for the purpose of prohibiting protected rights. The restrictions imposed by Uzbek law, however, are an impermissible violation of religious expression and association. Statements by Uzbek officials make it clear that the law is intended to stifle freedom of religion. President Karimov, for example, said that the new law was necessary because, “Today’s main task is to fight against all appearances of Islamic fundamentalism and religious extremism.”139 Another government official said the law was meant to counter the alleged threat of “aggressive Wahhabism.”140 The criminal, in addition to administrative, penalties for violations of the 1998 law also indicate the law’s prohibitive intent.141

Criminalization of Independent Belief and Practice

The 1998 law proscribes numerous aspects of religious activity. Punishments enforcing these proscriptions were set out in amendments made in 1998 and 1999 to the administrative and criminal codes. Infractions of most articles of the 1998 religion law were to be punished under the administrative code if the infraction was a first offense. Repeat offenses were to be punished by harsh prison sentences, established in two sets of amendments to the criminal code. In practice, courts have handed independent Muslims prison sentences for first-time offenses relating to religious activity.

Most relevant in the campaign against independent Islam are articles of the criminal code relating to illegal distribution of religious literature, membership in a banned religious organization, and unsanctioned teaching of religion. These legal cornerstones of the campaign are outlined below.

Exchange of Information

Uzbek law criminalizes expression of “religious extremism,” “separatism,” and “fundamentalism.” Article 5 of the 1998 law proscribes such expression, stating: “The state shall not…allow religious or other fanaticism and extremism.”142 Article 19 of the 1998 law states that persons who produce, store, and distribute materials—including printed documents, video and audio cassettes, films, and photographs—that “contain ideas of religious extremism, separatism and fundamentalism” will be held accountable under the law.143 Neither the law nor any internal regulations provide standards for evaluating at what point religious literature becomes “extremist,” or “fundamentalist,” and in practice the government has used these vague ideological labels to imprison and silence people whose views it did not want openly expressed.

The 1998 criminal code was amended to include a provision—article 244-1—corresponding to the restrictions under article 19 of the 1998 law, making possession and distribution of literature containing ideas of “religious extremism, separatism, and fundamentalism” a serious offense. These terms and phrases are nowhere defined. Under the new article 244-1 of the criminal code, producing and storing, with the goal of distributing, materials that contain “ideas of religious extremism, separatism and fundamentalism” became punishable by up to three years in prison. Distribution of literature deemed to fall into one of these categories carries with it a maximum sentence of five years in prison. Under such aggravated circumstances as dissemination after agreeing with a group of people to do so, by using one’s official position, or using financial assistance from a religious organization, foreign state, group, or person, the offense is punishable by up to eight years in prison.

Article 244-1 emerged as one of the cornerstones of the government’s campaign against independent Muslims. Members of Hizb ut-Tahrir, in particular, were tried and convicted under it.

Article 244-1 conflates the above-mentioned ideas with a prohibition on “calls for massacres or the forced eviction of citizens,” and materials aimed at “sowing panic.”144 No distinction is made between peaceful expression of “fundamentalist” ideas and outright calls for violence, including massacres. This misleading association of two different types of expression appears to be an attempt by the legislation’s authors to associate “fundamentalism” with calls for violence, and to smear certain religious ideas and identities.145

The 1998 amendments to the criminal code also included new language outlawing the import of literature “propagating religious extremism, separatism and fundamentalism,” labeling it as contraband, and setting a penalty of up to ten years in prison.146

The 1999 amendments to the criminal code added article 244-2, which invoked the same undefined “extremist” label to impose stricter criminal penalties for membership in a group that holds certain ideas: “Setting up, leading and participating in religious extremist, separatist, fundamentalist or other banned organizations are punishable by five to fifteen years of imprisonment with the confiscation of property.”147 The same actions, if they entail “serious consequences,” are punishable by fifteen to twenty years of imprisonment with confiscation of property. This charge, particularly when levied in combination with article 216, which bans participation in an illegal religious organization, results in the maximum punishment, twenty years in prison, for holding a set of ideas in conjunction with others.

Proscriptions on Unregistered Religious Rites, Worship, and Association

Article 14 of the 1998 law bestows the right to perform religious rites and worship to religious organizations and not to individuals. It also restricts the types of groups that may exercise this right. Under articles 8 and 11, only registered religious organizations have the right to function as legal entities and thus engage in rites and worship. Article 8 states that, “Religious organizations obtain the status of a legal subject and can carry out their activities after their registration….” Article 11 warns that religious leaders who evade registration will be punished under the law and, further, that “Officials who allow activity of non-registered religious organizations shall bear responsibility in accordance with the law.” Since only registered religious organizations have the right to carry out religious ceremonies and worship, the legislation effectively criminalizes unregistered religious rites and observance.

Regarding registration, the prohibitive aspect of the 1998 religion law and related amendments to the criminal code stands in sharp contrast to the 1991 law. Under the latter, a religious organization or group had to have as members ten citizens over the age of eighteen. Such groups had full rights not only to congregate for worship, but also to produce and distribute religious literature and impart religious education. Under the 1998 law, religious organizations—defined by membership of at least 100 citizens over the age of eighteen—have the right to gather for worship. In order to enjoy the right to produce or distribute literature or impart religious education and other essential activities, religious organizations must first establish a “central administrative body.” In order to establish a central administrative body, adherents of a given confession must organize a constituent conference of their registered religious organizations from no less than eight separate provinces of the country (thus, 800 members from eight provinces are now required where only ten were previously).148

The central administrative body must be headed by an Uzbek citizen deemed by the government to be qualified and registered with the Ministry of Justice, or headed by a foreigner approved by the Committee on Religious Affairs.149 Only after registering this central body do adherents possess the right to produce and impart information.150

The government abuses the legitimate process of registration to ensure the prohibition of religious associations it views as hostile. The registration issue, while at first glance benign, is one of the government’s chief weapons against independent Islam.

This restriction of the right to association was one of the main aims of the 1998 religion law. On September 30, 1998, then-Minister of Justice Sirojiddin Mirsafaev wrote, “Registering and re-registering all religious organizations with the Ministry of Justice and its bureaux [sic] were the most important requirements for ensuring the implementation of this law, because arbitrariness and unruliness in this sphere had gone beyond all measure….”151 Minister Mirsafaev went on to link unregulated religious leaders with criminality and to equate the disparate phenomena of violent crime and expression of ideas that the minister did not share. He stated: “Self-styled clerics made certain of such establishments as their ‘bases,’ dens of crime, and committed theft, robbery with violence, and spread false ideas in order to get rich and get publicity.”152

Under the law, failure to register a religious organization not only means that it will not enjoy certain rights, it means that the group is illegal, and that its membership is criminalized. Article 216 of the criminal code sets out penalties for involvement in an unregistered religious organization. Under article 216, as amended on May 1, 1998, organization of, or participation in, the activities of a “prohibited religious organization” is punishable by up to five years in prison.153 The way in which a group might earn the status of a “prohibited organization” is not defined. However, the meaning of this language is informed by requirements and limitations elsewhere in the law; broadly but most importantly legal status is realized through registration with and prior sanction by the state.

The 1998 amendments also created article 216-1, imposing sentences of up to three years in prison for the crime of persuading others to join a prohibited religious group, and article 216-2, setting out a three-year prison sentence for religious leaders who fail or refuse to register their group.154

Under article 201-2 of the administrative code, any person found violating the state rules on religious meetings, street processions, or “cult ceremonies” would be fined or placed under arrest for up to fifteen days. This, like other administrative code articles, appears to have been rarely if ever invoked in the campaign against independent Muslims.

Proselytism Outlawed

Article 5 of the 1998 religion law forbids proselytism, stating, “Actions aimed at converting believers of one religion into another (proselytism) as well as other missionary activity are prohibited.” The Soviet version of the law similarly prohibited missionary activity.155

The penalties for proselytism and missionary activity are set out in the 1998 amendments to article 240 of the administrative code, and to article 216-2 of the criminal code. As with other offenses under Uzbek law, the first violation carries a fine or period of detention under the administrative code.156 Persons found guilty of subsequent infractions are punished under article 216-2 of the criminal code and may be fined fifty to one hundred times the monthly minimum wage, sentenced to up to six months of administrative arrest, or sentenced to up to three years in prison. In practice, those charged with violation of this and all other provisions of the religion law rarely have been punished under the administrative code, even for a first offense, and, instead, have been tried under the criminal code and given the maximum punishment.

The ban on proselytism has far-reaching implications for individuals and religious groups that see it as their religious duty to call on or encourage others to join in their beliefs or practice. The prohibition on such “missionary” activity violates not only the right to freely express one’s belief, and the right to exchange views, it also effectively removes the individual’s right to observe his or her own religious faith, a crucial component of which is attempting to convert others. This provision thereby casts legitimate religious practice as a crime.

Limiting Expression and Education: The Ban on Private Religious Teaching

Article 9 of the 1998 religion law prohibits the “private teaching of religious principles.” Similar to the right to publish and disseminate religious material, the right to instruct others in religion is conditioned on membership in a registered religious organization that has met all of the requirements set forth in article 8, including establishment of a central administrative body. Once this is done, the central administrative body of a given religious organization must obtain a license and register with the Ministry of Justice before it can legally train clergy and others.157 Failure to fulfill these requirements brings with it punishment under the law.

With article 9 of the 1998 law, the government of Uzbekistan sought to put a stop to any religious education or activity that was beyond its control. It is illegal to impart religious education outside the framework of a government sanctioned central administrative body of a religious organization. Private citizens may not teach religious subjects. This is a particularly significant prohibition for Uzbek society, given that, historically, religious traditions and precepts were passed on to younger generations and largely kept alive during the Soviet period through private religious education. During the Soviet era, this private Islam thrived separately from officially sanctioned Muslim activity that was controlled by the state and therefore has been termed “parallel Islam.” This phenomenon of coexistence of official and private Islam characterized the later Soviet period, despite restrictions on paper.

The 1998 amendments to the criminal and administrative codes added penalties for engaging in private religious instruction, showing the seriousness with which the government of Uzbekistan approached this prohibition. Article 241 of the administrative code, as amended in 1998, prescribes a fine of five to ten times the monthly minimum wage or fifteen days administrative arrest for violators.158 Second offenses are punished under article 229-2 of the criminal code, entitled, “Violation of the Order Regarding Teaching of Religious Dogmas.” It states, “Teaching religious dogmas without special religious education and without permission of the Central Administrative Board of [a given] Religious Organization, as well as teaching religious dogmas in private” can result in punishment of up to three years in prison.159

Other Aspects of the Religion Law

Religious Attire

Article 14 of the religion law explicitly bans Uzbekistan’s citizens from wearing “religious attire,” translated also as “cult dress,” in public places, unless they are members of the clergy. This provision had no counterpart in the 1991 Soviet law, and has emerged as one of the most controversial new rules in Uzbekistan. The 1998 amendment to the administrative code, article 184-1, envisions penalties ranging from a fine equal to five to ten times the minimum monthly wage to fifteen days under administrative arrest for violation of this clause. The prohibition on religious garb clearly violates international instruments establishing the right to manifest one’s belief.160

The application of this law has been one element of the discriminatory government campaign against independent Muslims. Government officials and academic administrators alike used the prohibition on religious dress to retroactively justify expelling from school and university women students who wore headscarves that covered their faces prior to the law’s adoption. It has also established quasi-legal grounds for police surveillance and, ultimately, harassment of women in full hijab (meaning clothing that covers the body and face) and many men with beards.161

Religious Parties Banned

Article 5 of the religion law reiterates the constitutional ban on political parties with a religious platform. The prohibition on political parties with a religious character was also outlined in the 1991 precursor to this law.162

Application of Existing Statutes in the Arrest Campaign

In addition to articles in the statutes amended in 1998 and 1999 to accompany a stricter religion law, three articles of the criminal code that do not derive from the religion law are also among the primary legal tools used to prosecute independent Muslims. These relate to subversion, organization of a criminal group, and inciting ethnic, racial, or religious enmity.

Subversion

Perhaps the most important and common legal statute invoked in the state campaign against independent Muslims has been criminal code article 159, entitled Encroachment on the Constitutional Order of the Republic of Uzbekistan. In the years since 1997, prosecutors and judges have almost uniformly applied this charge, commonly referred to as “anti-state or anti-constitutional activities,” to cases involving Muslim religious dissidents.163

Article 159 states:

Public appeals to unconstitutionally change the existing governmental system, to seize power to remove from office legally elected or appointed representatives, or to unconstitutionally disrupt the territorial unity of the Republic of Uzbekistan, as well as distribution of material with such content are punishable with a fine of up to fifty times the minimum wage or imprisonment up to three years.

The law goes on to say that violent actions against the constitutional authorities carries a penalty of up to five years in prison. When undertaken repeatedly or by a group, perpetrators can be imprisoned for up to ten years.

Of particular significance to cases dealt with in this report is the provision in article 159 punishing conspiracy to “overthrow the constitutional order of the Republic of Uzbekistan” with ten to twenty years imprisonment and confiscation of property. Any call for an Islamic state, including the call by Hizb ut-Tahrir members for restoration of a Caliphate, absent any other actions and absent any threats or acts of violence, is considered by Uzbekistan’s authorities to be a crime under article 159.

Organizing a Criminal Group

In addition to invoking criminal code article 216, prescribing punishment for membership in an illegal religious group, Uzbek state authorities employed article 242, “organizing a criminal group,” to prosecute independent Muslims for their presumed membership in unregistered religious groups. Categorized as a crime against national security and social order, it punishes the establishment or leadership of a criminal society or group with up to twenty years in prison or the death penalty.164

Inciting National, Racial, or Religious Enmity

Article 156 refers to incitement of national (ethnic), racial, or religious enmity. In addition to outlawing acts that directly infringe on the rights of others or lead to the physical harm of others, it states that, “Willful action that denigrates national (ethnic) honor or dignity or which offends citizens on the basis of their religious (or atheistic) beliefs, committed with the goal of inciting animosity, intolerance, or discord…is punishable by imprisonment of up to five years.” If actions deemed to fall under this statute are undertaken by prior collusion or by a group, or under other aggravated circumstances, they are punishable with up to ten years in prison. Uzbek prosecutors and judges routinely interpreted this provision as applicable to the possession or distribution of literature. Neither the criminal code nor any other legislation or government regulation defines denigration of a group’s honor and dignity or an offense to an individual, leaving the interpretation to judicial and executive authorities. The opportunities for arbitrary application of this article are apparent and examples are provided in subsequent chapters of this report.

It is worth clarifying that the government of Uzbekistan does not prosecute Hizb ut-Tahrir members for hate speech, if defined as incitement to violence.165 Rather, Hizb ut-Tahrir members and other independent Muslims have been charged under article 156 of the criminal code, which punishes speech that “insults” ethnic, national or other groups. The International Covenant for Civil and Political Rights, article 19, which provides for freedom of speech and expression, allows for exceptions only when necessary “For respect of the rights or reputations of others” or “For the protection of national security or of public order (ordre public), or of public health or morals.” The government of Uzbekistan has failed to recognize the right of Hizb ut-Tahrir members to freedom of speech and has instead jailed, tortured, and tried them, with no due process, for their belief in a Caliphate, for exchange of opinions including those in favor of a Caliphate, and for membership in a pro-Caliphate organization.

Common Crimes: Drugs and Weapons Charges

Independent Muslims were routinely brought up on fabricated charges of illegal possession of narcotics (criminal code articles 273 and 276) or illegal possession of weapons or ammunition (criminal code article 248). These charges do not relate directly or logically to religiosity, but were fabricated by police and applied in an arbitrary way by state prosecutors and judges so universally that they became core elements of the government campaign. These phenomena are explained further in other chapters of this report.

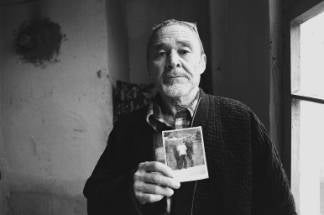

Usman Iusupov, age 64, with a photograph of one of his sons, an imprisoned independent Muslim. Two of his sons are currently in prison for membership in Hizb ut-Tahrir. Margilan city, Fergana Valley.

© 2003 Jason Eskenazi

Oiparcha Mirzamatova and her daughter-in-law, with photographs of male relatives imprisoned on religion-related charges. Mirzamatova's son, Ibrokhim Khaidarov, is serving a sixteen-year sentence for membership in Hizb ut-Tahrir. Her daughter-in-law's brother, Khurshid Oripov, was arrested on religion-related charges and died apparently from torture in custody. At least two other male relatives are in prison on similar charges. Margilan city, Fergana Valley.

© 2003 Jason Eskenazi

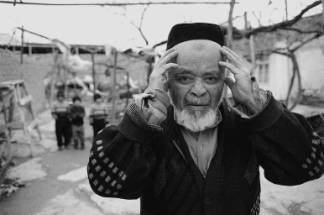

Akhmedjon Madmarov, age 58, with a letter from his son, Hamidulla, imprisoned in Karshi on religion-related charges. Madmarov has two other sons in prison on similar charges. Margilan city, Fergana Valley.

© 2003 Jason Eskenazi

Former religious prisoner Bakhodir Ulmasov, who suffered head trauma and other serious injury from mistreatment in prison. His brother (shown in smaller photograph) was also imprisoned on religion-related charges. Margilan city, Fergana Valley.

© 2003 Jason Eskenazi

Sadik Vahobov, age 75. His son was arrested while praying in public in commemoration of a friend who had died in prison. He is serving an eighteen-year sentence on religion-related charges. Margilan city, Fergana Valley.

© 2003 Jason Eskenazi

89 The “Wahhabi” label has also been used in other parts of the former Soviet Union as short-hand for militant. According to Central Asia scholar Mehrdad Haghayeghi, the term was first used by the Soviets to refer to “fundamentalist” Muslims in general during the 1980s. Mehrdad Haghayeghi, Islam and Politics in Central Asia, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1995, p. 227, note 55. In the Tajik civil war, fighters seeking to overthrow the government were nicknamed “vofchiki,” a diminutive form of “Vahabit,” or “Wahhabi.”

90 Mehrdad Haghayeghi, Islam and Politics in Central Asia, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1995, p 95. While the Wahhabi doctrine rejects reinterpretation of the Koran and hadith, it does allow for ijtihad, or independent reasoning, in other areas.

91 Jihad: The Rise of Militant Islam in Central Asia, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002, p. 45.

92 Islam and Politics in Central Asia, p. 92.

93 Ibid. p. 81.

94 Ibid, p. 81.

95 Ibid. p. 95

96 Jihad, p. 46

97 For example, Navruz (celebration of the new year).

98Islam and Politics in Central Asia, pp. 80-81

99 Hizb ut-Tahrir materials often denounce Israeli occupation of Palestine and Israeli conduct in the conflict there.

100 The German Ministry of the Interior issued a statement on January 15, 2003 announcing that Hizb ut-Tahrir was banned in the country. http://www.bmi.bund.de/dokumente/Pressemitteiling/ix_91334.htm. The ministry statement cited as grounds for the decision, paragraphs 3, 14, 15, and 18 of the German Vereinsgesetz (congregation laws). German Minister of the Interior Otto Schilly said that, “Hizb ut-Tahrir abuses the democratic system to propagate violence and disseminate anti-Semitic hate-speeches. The organization wants to sow hatred and violence.” He also stated that, “The organization supports violence as a means to realize political goals. Hizb ut-Tahrir denies Israel’s right to exist and calls for its destruction. The organization further spreads massively anti-Semitic propaganda and calls for killing Jews.” See also, Peter Finn, “Germany Bans Islamic Group; Recruitment of Youths Worried Officials,” The Washington Post, January 16, 2003. That article states that German officials accused Hizb ut-Tahrir of spreading “violent anti-Semitism” and establishing contacts with neo-Nazis. In April, German police searched the homes of more than eighty people suspected of supporting Hizb ut-Tahrir. No arrests were made. See, Associated Press, “Germany stages new raids against banned Islamic organization,” April 11, 2003.

101 On February 14, 2003, Russia’s Supreme Court, acting on a recommendation from the Office of the Prosecutor General, designated Hizb ut-Tahrir a terrorist organization. According to a press statement released by Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs on June 9, 2003, “The main criteria for the inclusion of organizations in the list of terrorist outfits were: the carrying out of activities aimed at a forcible change of the constitutional system of the Russian Federation; ties with illegal armed bands, as well as with radical Islamic structures operating on the territory of the North Caucasus region, and ties with or membership of organizations deemed by the international community terrorist organizations.” “On the Detention of Members of the Terrorist Organization ‘Islamic Liberation Party’ (‘Hizb ut-Tahrir al Islami’),” Publication of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, Information and Press Department, June 9, 2003, from the Daily News Bulletin, posted June 11, 2003. http://www.ln.mid.ru/bl.nsf/0/43bb94f12ad12c7543256d42005a9b49?OpenDocument On June 6, 2003, fifty-five people alleged to be members of Hizb ut-Tahrir were detained in Russia. Two of the men arrested—one a citizen of Kyrgyzstan, the other a citizen of Tajikistan—were accused of illegal possession of grenades and explosive material. Ibid. As of this writing, Human Rights Watch had no further information about the fate of these two men or whether they were convicted on these charges. The Russian rights group Memorial contested the significance of the law enforcement action, however. The group noted that the majority of the men detained were immigrant workers at a bakery and were released soon after the sweep. “Russian rights group: Detention of 55 'Islamic extremists' was sham,” Associated Press, June 25, 2003.

102 In a recent expression of this view, Larry Memmot, then-first secretary of the U.S. Embassy in Tashkent, told Human Rights Watch that this is “not an issue of religious repression, but political.” Human Rights Watch interview, Tashkent, May 4, 2003. Whether the U.S. government views those arrested on charges related to Hizb ut-Tahrir membership victims of religious persecution has important legal and foreign policy consequences. Under the U.S. International Religious Freedom Act, the U.S. government annually must determine whether governments engage in religious persecution. If the executive finds that governments “have engaged in or tolerated particularly severe violations of religious freedom,” it must choose from a menu of actions, ranging from private demarches through sanctions, with regard to that country.

103 See “The Legal Setting” in Chapter II.

104 Human Rights Watch unofficial transcript, Tashkent City Court trial held in the Chilanzar District Court building, Tashkent, June 30, 1999. For examples of the specific wording of Hizb ut-Tahrir oaths, See “Hizb ut-Tahrir” in Chapter II.

105 Although not charged with involvement in or responsibility for a specific violent act, some Hizb ut-Tahrir members, particularly in Andijan, have been convicted for terrorism under article 155 of the criminal code. Human Rights Watch’s review of these cases found no reference to a violent act having taken place. In one case following the September 11, 2001 attacks in the United States, nine Hizb ut-Tahrir members tried in Tashkent were alleged by the procurator to have links to Osama Bin Laden and al-Qaeda. However, according to trial observers, no evidence was provided to back this claim. One journalist who covered the process described the nature of the alleged connection a “mystery” and quoted defendant Nurullo Majidov’s rejection of the state’s charges, “We do not have connections to Osama Bin Laden or any other terrorist organizations, as we pursue different methods of struggle. We are fighting for our ideas through peaceful means.” Said Khojaev (a pen name), “Tashkent Cracks Down on Islamists,” Institute for War and Peace Reporting, October 12, 2001. The nine men were convicted in October 2001 to prison terms ranging from nine to twelve years. Hizb ut-Tahrir members in the U.K. also denied that the organization had any ties with Bin Laden or al-Qaeda. Human Rights Watch interview with members of the leadership committee of Hizb ut-Tahrir Britain, London, June 29, 2002.

106 Ahmed Rashid, “Interview with Leader of Hizb-e Tahrir,” The Analyst, available on Eurasianet.org [online] http://www.eurasianet.org/resource/cenasia/hypermail/200011/0066.html (retrieved May 9, 2003).

107 Human Rights Watch interview with a member of Hizb ut-Tahrir, name withheld, Tashkent, February 2001.

108 Human Rights Watch unofficial transcript, Tashkent City Court trial held in the Chilanzar District Court building, Tashkent, June 30, 1999.

109 Ibid.

110 Ibid.

111 Ibid.

112 Human Rights Watch unofficial transcript, Tashkent City Court trial held in the Chilanzar District Court building, Tashkent, July 20, 1999.

113 Hizb ut-Tahrir web site [online], http://www.hizb-ut-tahrir.org/ (retrieved May 9, 2003).

114 Ibid.

115 One example of this claim can be found in “The Ideology the President of Uzbekistan, Karimov, Wants to Impose upon Muslims,” Hizb ut-Tahrir leaflet, Uzbekistan, July 24, 2000 [online], http://www.khilafah.com/home/lographics/category.php?DocumentID=189&TagID=3 (retrieved May 9, 2003). The leaflet states: “To fight the idea of Khilafah, [the Karimov government] first announced that the Khilafah concept contradicts Islam, they claimed it contradicts the method of the Great Imam Abu Hanifah, but when Muslims realized that the Khilafah is the only way to apply Islam and its shariah in full accordance with Islam and with the method of Abu Hanifah, their plot became obvious and failed.”

116 The group’s writings also hold that criticism of an unjust ruler is the duty of all Muslims. Hizb ut-Tahrir’s draft constitution, which envisions the order that would be in place in a future Caliphate, says, “Calling upon the rulers to account for their actions is both a right for the Muslims and a fard kifayah (collective duty) upon them.” [Article 20 of the draft constitution of Hizb ut-Tahrir ; see, Hizb ut-Tahrir, “A Draft Constitution,“ in The System of Islam (London: Al-Khilafah Publications, 2002), [available online], http://www.hizb-ut-tahrir.org/english/ (retrieved February 22, 2004). Criticizing unjust rulers, then, is a distinctly religious action, as it is viewed as a prerequisite to creation of a worldwide Muslim community, to be awarded by God with an Islamic form of government, or Caliphate.

117 Hizb ut-Tahrir also says that it does not accept a religious system bereft of politics any more than it would accept a political order that was not based on Islam. This is articulated in the book, The System of Islam, a principle Hizb ut-Tahrir text, which reads, “…anything that confines religion to the spiritual dimension, separating it from politics and ruling should be abolished.” Hizb ut-Tahrir, The System of Islam, p. 40.

118 Human Rights Watch unofficial transcript, Tashkent City Court trial held in the Chilanzar District Court, Tashkent, June 30, 1999.

119 Ibid.

120 One leaflet states, “Being perfect and complete, Islam has the right to rule the world.” See, “Government of Uzbekistan Displays the Decline of Systems of Belief,” Hizb ut-Tahrir leaflet, April 9, 2000 [online], http://www.khilafah.com/home/lographics/category.php?DocumentID=84&TagID=3 (retrieved May 9, 2003.)

121 “The Ideology the President of Uzbekistan, Karimov, Wants to Impose upon Muslims,” Hizb ut-Tahrir leaflet, Uzbekistan, July 24, 2000 [online], http://www.khilafah.com/home/lographics/category.php?DocumentID=189&TagID=3 (retrieved May 9, 2003). The leaflet states: “Because Islam is the ideology and system capable of completely solving all problems and leading to an unconditional correct development….Islam is a religion, revealed by Allah to its Messenger Muhammad (the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him). Therefore, we submit ourselves to Islam not because our ancestors did, but because it is a true religion revealed by Allah, and we obey its rules and call to it as Allah orders us.”

122 This idea is expressed in an April 24, 2000 leaflet entitled “The President of Uzbekistan Admits to Being Intellectually Bankrupt.” It states: “The creed of the people in the Islamic world is the Islamic creed and the creed of Islam is one from which a system emanates organizing all affairs of the people. And this system is the only correct system for the world because it comes from Allah (swt). And every attempt to separate the creed from the system or to mix and patch together different creeds and systems is a consequence of shallow thinking and its outcome is failure.” The leaflet is available at: http://www.khilafah.com/home/lographics/category.php?DocumentID=1&TagID=3 (retrieved May 9, 2003).

123 “Government of Uzbekistan Displays the Decline of Systems of Belief,” Hizb ut-Tahrir leaflet, April 9, 2000 [online], http://www.khilafah.com/home/lographics/category.php?DocumentID=84&TagID=3 (retrieved May 9, 2003).

124 “The Ideology the President of Uzbekistan, Karimov, Wants to Impose upon Muslims,” Hizb ut-Tahrir leaflet, Uzbekistan, July 24, 2000 [online], available at: http://www.khilafah.com/home/lographics/category.php?DocumentID=189&TagID=3 (retrieved May 9, 2003).

125 Ibid.

126 Hizb ut-Tahrir, “The President of Uzbekistan Admits to Being Intellectually Bankrupt,” Hizb ut-Tahrir leaflet, April 24, 2000 [online], http://www.khilafah.com/home/lographics/category.php?DocumentID=1&TagID=3 (retrieved May 9, 2003).

127 “Government of Uzbekistan Displays the Decline of Systems of Belief,” Hizb ut-Tahrir leaflet, April 9, 2000 [online], http://www.khilafah.com/home/lographics/category.php?DocumentID=84&TagID=3 (retrieved May 9, 2003.)

128 Hizb ut-Tahrir, “The President of Uzbekistan Admits to Being Intellectually Bankrupt,” Hizb ut-Tahrir leaflet, April 24, 2000 [online], http://www.khilafah.com/home/lographics/category.php?DocumentID=1&TagID=3 (retrieved May 9, 2003). This statement is apparently inspired by sura “The Table” [5:82 of the Koran]: ”You will find that the most implacable of men in their enmity to the faithful are the Jews and the pagans…” The Koran, Penguin Books, London, England, 1990, p.88. Translated into English.

129 Ahmed Rashid, “Interview with Leader of Hizb-e Tahrir,” The Analyst, November 22, 2000.

130 Under article 4, the ICCPR allows state parties to derogate from certain articles of the covenant in times emergency that threaten the life of the nation. Article 4 does not permit states to derogate from a number of articles, among them article 18.

131 Human Rights Committee, General Comment 10, Article 19 (Nineteenth session, 1983). Compilation of General Comments and General Recommendations Adopted by Human Rights Treaty Bodies, U.N. Doc. HRI\GEN\1\Rev.1 at 11 (1994).

132 Human Rights Committee, General Comment 22, Article 18 (Forty-eighth session, 1993). Compilation of General Comments and General Recommendations Adopted by Human Rights Treaty Bodies, U.N. Doc. HRI\GEN\1\Rev.1at 35 (1994).

133 Ibid.

134 Article 18 (2) states, “No one shall be subject to coercion which would impair his freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief of his choice.”

135 Human Rights Committee, General Comment 22, Article 18 (Forty-eighth session, 1993). Compilation of General Comments and General Recommendations Adopted by Human Rights Treaty Bodies, U.N. Doc. HRI\GEN\1\Rev.1at 35 (1994).

136 Ibid.

137 The 1998 law replaced the law on religion enacted at the end of the Soviet era on June 14, 1991, three months prior to independence. All citations from the 1998 religion law are from the English translation of the law in BBC Monitoring, May 20, 1998, translated from the original publication of the law in Russian in Narodnoe Slovo, May 15, 1998.

138 Law of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Amendments and Additions to some Legal Acts of the Republic of Uzbekistan, May 1, 1998.

139 Uzbek Radio first program, May 11, 1998, English translation in BBC Monitoring, May 11, 1998.

140 BBC Worldwide Monitoring, quoting Interfax, May 1, 1998.

141 Uzbek law enforcement and judicial authorities have also ignored the provision of the religion law recognizing the supremacy of international over domestic law regarding freedom of conscience and religious organizations. Article 2 of the 1998 law states, “If an international agreement of the Republic of Uzbekistan sets rules different from those stipulated in the legislation of the Republic of Uzbekistan, regarding freedom of conscience and religious organizations, the provisions of the international agreement shall apply.”

142 Article 5, Law on Freedom of Conscience and Religious Organizations, May 1, 1998.

143 Article 19, Law on Freedom of Conscience and Religious Organizations, May 1, 1998.

144 Law of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Amendments and Additions to some Legal Acts of the Republic of Uzbekistan, May 1, 1998.

145 Article 244-1 states: “Preparation or possession, with the aim of disseminating, of materials containing ideas of religious extremism, separatism or fundamentalism, calling for pogroms or forcible eviction of citizens, or intended to create panic among the population, committed after administrative punishment has been levied…” carries punishment ranging from a fine equal to fifty times the minimum wage to three years in prison. Meanwhile, “Preparation or possession, with the aim of disseminating, of materials containing ideas of religious extremism, separatism or fundamentalism, calling for pogroms or forcible eviction of citizens, or intended to create panic among the population, as well as use of religion to disturb the harmony of the citizenry, spreading slander, destabilizing the situation through deception, and committing other acts aimed against the established regulations for public conduct and public safety” are punishable with up to five years in prison. Those people found to have committed the above infractions under aggravating circumstances—“by preliminary agreement or as part of a group, by using one’s official position, or with the financial or other material help of a religious organization or foreign government, organization or citizen”—can be sentenced to up to eight years in prison.

146 Article 246 of the criminal code, as amended in 1998.

147 A number of punishments spelled out in Uzbekistan’s criminal code include confiscation of property. Execution of this sentence can result in negative consequences for members of the convicted person’s family as well as for the individual.

148 According to the Ministry of Justice, Presidential Decree 882, signed on August 14, 1998, allows for registration of religious groups with smaller congregations if and when a special commission of the Ministry of Justice deems it appropriate. Khalq Sozi (The People’s Word)(Tashkent, Uzbekistan), September 30, 1998, English translation in BBC Monitoring, November 11, 1998.

149 Article 8, Law on Freedom of Conscience and Religious Organizations, May 1, 1998.

150 Article 19 of the religion law states that “‘Religious organizations’ central administrative bodies have a right to produce, export, import and distribute the religious items, religious literature and other materials with a religious content in the order established by the law…Delivery and distribution of religious literature published abroad is allowed after its content is examined…Religious organizations’ central administration bodies have an exclusive right to publish and distribute religious items provided they have a corresponding license….” Law on Freedom of Conscience and Religious Organizations, 1998.

151 Khalq Sozi, September 30, 1998, English translation in BBC Monitoring, November 11, 1998.

152 Ibid.

153 In 1999, article 216 was again amended to change the reference to “prohibited” or “banned” groups to “illegal public associations or religious organizations;” the penalty remained unchanged. Law of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Amendments and Additions to Certain Legislative Acts of the Republic of Uzbekistan, dated April 15, 1999, printed in Narodnoe Slovo, Tashkent, May 12, 1999, English translation in BBC Monitoring, May 13, 1999. Hizb ut-Tahrir is frequently referred to as a “banned” organization, leading some to believe that the government singled it out for prohibition. However, its “banned” or “prohibited” status derives from its lack of registration and from the “religious extremism” the government ascribes to it.

154 Article 216-2 has rarely been invoked. Instead, prosecutors routinely levy and judges employ the principle provision, article 216, which carries a stiffer penalty, up to five years in prison. Also under article 216-2, members of unregistered religious organizations who “organiz[e] and [hold] special meetings for children and youth as well as labor, literature and other circles and groups that are not connected with performance of religious rites by the servants and members of religious organizations” face a sentence of up to three years imprisonment.

155 Article 7, Law on Freedom of Conscience and Religious Organizations, June 14, 1991.

156 Article 240, “Violation of the Laws on Religious Organizations,” allows authorities to punish proselytism with a fine equal to five to ten times the monthly minimum wage—3,535 som, approximately U.S. $4, in 2003—or administrative arrest for up to fifteen days. In April 2003 the Labor and Social Security Ministry announced this figure for the minimum wage. Uzland.uz web site, in Russian, April 1, 2003, English translation in BBC Monitoring, April 1, 2003.

157 Article 9, Law on Freedom of Conscience and Religious Organizations, May 1, 1998.

158 Law of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Amendments and Additions to some Legal Acts of the Republic of Uzbekistan, May 1, 1998.

159 Ibid.

160 As noted above, the U.N. Human Rights Committee has stated that, “The observance and practice of religion or belief may include not only ceremonial acts but also such customs as the observance of dietary regulations, the wearing of distinctive clothing or head coverings, participation in rituals associated with certain stages of life, and the use of a particular language customarily spoken by a group.” Human Rights Committee, General Comment 22, Article 18 (Forty-eighth session, 1993). Compilation of General Comments and General Recommendations Adopted by Human Rights Treaty Bodies, U.N. Doc. HRI\GEN\1\Rev.1at 35 (1994).

161 For more information, see: Human Rights Watch, “Class Dismissed: Discriminatory Expulsions of Muslim Students,” A Human Rights Watch Report, Vol. 11, No. 12 (D), October 1999.

162 Article 7, Law on Freedom of Conscience and Religious Organizations, June 14, 1991.

163 The primary exception to the application of article 159 to those charged with religious infractions is in cases involving membership in Hizb ut-Tahrir under so-called mitigating circumstances. Specifically, if a person charged with membership in the group claims that he or she became a member “accidentally,” that he or she is in fact not a member at all, or that he or she stopped attending the group’s study sessions and did not participate in distribution of the group’s literature, then that person has, in some cases, avoided prosecution under article 159 and is most routinely charged under article 216, punishing membership in an illegal religious organization, which carries a shorter maximum prison term.

164 As of this writing, there were no known cases of an independent Muslim being sentenced to death under this particular article.

165 In none of the cases cited in this report are independent Muslims prosecuted for speech that was demonstrated to be a direct and imminent incitement to violence.

<<previous | index | next>> | March 2004 |