IV. CASE STUDY: POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND INTIMIDATION IN TBONG KHMUM

Tbong Khmum district in Kompong Cham province saw some of the worst violence and intimidation of the Cambodian commune election period. A double killing in Sralop commune, followed by a sustained campaign of intimidation directed against opposition candidates, showed clearly the impact of political violence on the democratic process and the impunity enjoyed by local officials suspected of involvement in violations. The ongoing murder investigation also demonstrates the importance of international pressure on the Cambodian government to pursue and prosecute suspected offenders.

Kompong Cham

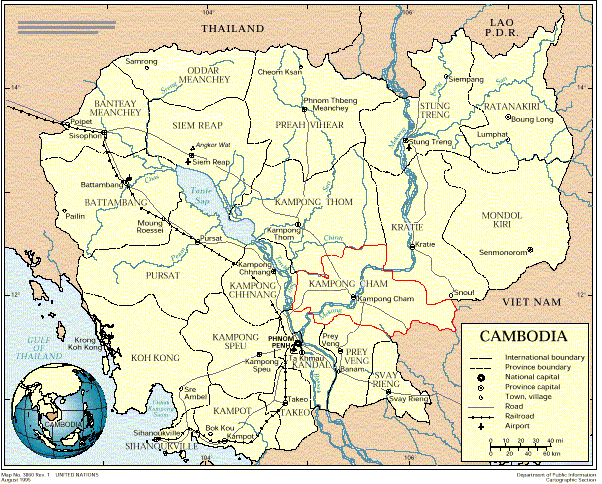

Kompong Cham province straddles the Mekong River northeast of Phnom Penh, and borders Vietnam to the east. Cambodia's most populous province and the heart of the lucrative rubber industry, it also has a long and bloody history of conflict. Situated along a key trade route, its strategic military significance has placed it at the center of warfare in Cambodia. During the Indochina wars, districts east of the Mekong saw heavy fighting involving not only Cambodian forces and Khmer Rouge guerillas, but also units of the Viet Cong and North and South Vietnamese armies. Under the rule of the Khmer Rouge (KR), Kompong Cham witnessed some of the worst atrocities directed against Cambodian civilians, as well as extensive purges of KR cadre as the regime began to turn in on itself. Following their ouster from power, the Khmer Rouge retained bases throughout the province until reintegration efforts commenced in 1996.

The province now serves as the base for the Royal Cambodian Armed Force' Military Region 2 (MR2), an area also encompassing Kratie to the north, and Prey Veng and Svay Rieng to the south. According to local human rights groups, MR2 soldiers have been repeatedly implicated in serious human rights violations, from extortion and armed robbery to assault, rape, illegal detention and murder. Efforts to prosecute suspected offenders have been frustrated, with suspects failing to answer arrest warrants in the few instances where they have been issued.

Kompong Cham has historically been a CPP stronghold. The birthplace of Prime Minister Hun Sen, it was the area from which he and many other Khmer Rouge officers fled to Vietnam in 1977, fearing the growing purges in the KR's Eastern Zone. When they returned to Cambodia backed by the Vietnamese army two years later, Kompong Cham was the first province to fall. In the subsequent People's Republic of Kampuchea, Khmer Rouge defectors such as Hun Sen and Heng Samrin who had served in Kompong Cham and other eastern provinces took key positions in government. Hun Sen's brother, Hun Neng, was later appointed Kompong Cham governor.

Yet despite the province's strong association with the CPP, when U.N.-sponsored national elections were held in 1993 the population voted overwhelmingly for the royalist Funcinpec (FUN 53.9 percent, CPP, 30 percent). Funcinpec held the province in the 1998 elections, albeit with a significantly reduced majority (FUN 38.5 percent, CPP 34.2 percent), and also won the most votes in the district of Tbong Khmum.

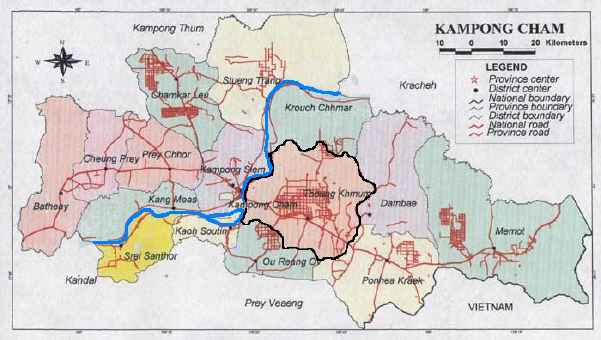

Tbong Khmum District

Tbong Khmum lies on the east side of the Mekong river, across a newly-constructed bridge from Kompong Cham provincial town and along National Road 7 to Vietnam. The road, currently the subject of a major reconstruction effort, cuts through Tbong Khmum, passing just south of the massive rubber plantation that lies at the heart of the district. Tbong Khmum is also fringed by smaller plantations in Kroich Chhmar district to the north, and O Reang Ov to the south, while important fishing concessions lie along the river to the west.

In addition to the military bases scattered throughout Tbong Khmum, the rubber and fishing concessions have long been a focus for violence. According to local human rights groups, police and military guards have repeatedly been implicated in cases of threat, assault and even murder while enforcing the illegal seizure and usage of concessions.

Tbong Khmum was the scene of some of the worst crimes in the run-up to the 1998 election, including numerous cases of threat and intimidation. The link between politics and violence was clear, for example in the June 1998 killing of Sam Rainsy Party activist Em Iem. A U.N. report documents the circumstances surrounding his death:

The investigation into the killing of Em Iem (c.10 June; Tbong Khmum, Kompong Cham) has established convincing evidence of a political motive. On the morning of 10 June 1998, Em Iem left his home on his bicycle to go to the district headquarters of the Sam Rainsy Party where he was working. He was witnessed being arrested by six men including the village chief, commune police and the militia chiefs. He was searched and party documents were seized. He was seen being handcuffed, blindfolded and taken in the direction of a nearby rubber plantation, where his body was found several days later in a shallow grave. The body was exhumed and identified on June 19. It showed damage to the left side of the head, to the back of the neck and to the right hand. Several teeth had been broken, the right jaw was broken and the nose was smashed. Witnesses said that on the night before the murder (June 9) the village chief had invited people to his home where he declared loudly that anyone joining a political party other than the CPP would be killed. The threat was reiterated several days after the murder, during a gift distribution ceremony, when he stated that Sam Rainsy Party members would be killed one after the other.6

Given their experiences in past elections, the residents of Tbong Khmum viewed the prospect of the February 2002 commune elections with strong apprehension. One voter, who claimed no affiliation to any political party, described the situation:

It is important to have the elections, as we want to choose for ourselves who will be commune chief. But we know that whenever there is voting, there will also be killing. So I am very worried about this election, as there is often killing and violence here.7

The year 2001 started badly in Tbong Khmum, with a murder that linked politics, access to resources and the military. On January 14, long-time Funcinpec member and prospective commune council candidate Chhay Than was shot dead in his home in Chiro Pi commune. Than, a fisherman, had been closely involved with advocacy for his fellow villagers against the confiscation of fishing lots and the use of illegal fishing methods by lot owners. The suspect in the killing - a soldier from a neighboring commune who worked guarding the fishing lots - remains at large. But worse was to come as the election drew near.

Double Killing in Sralop Commune

At around 6:20 p.m. on the night of November 14, 2001, people riding on two "motos" (small 100cc motorbikes commonly used throughout Cambodia) arrived at the house of Phoung Sophat in Veal Knach village, Sralop commune. Phoung Sophat, a member of the opposition Sam Rainsy Party, lived close to National Road 7 and the Sralop police post. He was not running as a candidate in the commune elections, but his wife described him as an enthusiastic supporter who was fond of calling on his drinking partners to vote for Sam Rainsy.

According to witnesses, the first moto drew up at the house and two men dismounted, calling for Sophat by his nickname of "Thur". They told Sophat's wife that they had come to see her husband on business, and she agreed to fetch him from a neighboring house where he was tending his sick aunt. She left, returning ten minutes later with her husband, and they together approached the second moto, which had stopped in the darkness a few meters away. As they neared the motorbike its passenger dismounted, took Sophat by the shoulder and shot him twice at point-blank range with a handgun, killing him instantly. The four perpetrators, three of whom were wearing military jackets, swiftly left the scene and headed west along National Road 7. There was no attempt to rob Sophat or his wife.

Two hours later, in the nearby village of Trapeing Dom, Funcinpec commune election candidate Thon Phally and his wife were awoken by the sound of people moving under their house (which, like many others in the area, is supported on long stilts). Coming to the door, they saw two men in military uniforms climbing the ladder towards them. Without a word, one man shone a flashlight in the face of Thon Phally, and the second shot him with a handgun. He died a few minutes later. Footprints under the house indicated that four or five men had been present, and had fled from the scene into rice fields to the east.

Later that night, reports indicate that two motos bearing three unknown men entered the compound of another Funcinpec candidate in a third village of Sralop. Fortunately for the candidate, he was not at home at the time, and the motos eventually departed.

Local police immediately dismissed the killings as due to unrelated personal disputes, and not in any way connected to politics.8 But as more evidence emerged, it became clear that the two killings constituted a deliberate act of intimidation against opposition parties in Sralop commune, the effects of which were to be felt throughout Tbong Khmum in the run-up to the commune elections and beyond.

The Preliminary Investigation

Soy Tha, Thon Phally's wife, was interviewed by the police the day after the murder. Shocked and terrified, she said that she did not know any of the attackers. But she was later to revise her statement in a way that made her initial reluctance to testify understandable. On November 21 she stated that she had recognized the man who pulled the trigger on her husband as Ian Saveth (commonly known as "Veth") - the deputy police chief of neighboring Longieng commune and son of the Sralop commune chief.9 Veth had been seen by several villagers hanging around the north end of Trapeing Dom village earlier on the afternoon of November 14, accompanied by his friend Lang Sarin ("Seth") - the deputy police chief of Sralop commune. Witnesses said the two had also been joined by three men in military uniform, riding on two motos.

There is no record that the police sought to question Veth, but they did speak that same day to his colleague Seth. Seth denied any involvement in the killing, but implicated three men: Yuon Samoeun, Yuon Thonny and Chorn Rotha - the same three who had been seen with Seth and Veth on the afternoon of the 14th.

Yuon Samoeun was the former chief of militia in Sralop commune, and the husband of Phuong Sophat's former sister-in-law. Yuon Thonny, his nephew, was also a former militia member in Sralop. Equipped with a uniform and weapon, local residents believed that he had become a member of the District Military - although he does not appear on their records. It is possible that he was registered under a false name, or that he was an "unofficial" soldier, equipped by officially serving officers to conduct extortion and intimidation for them. Chorn Rotha, a friend of the other two and former Khmer Rouge fighter, is a sergeant in the District Military.

On November 23, a warrant was issued against the three suspects, ordering them to be brought to the district court for questioning in the murder of Thon Phally. No action was taken against Veth or Seth, and no link was made to the killing of Phoung Sophat, despite the proximity and similarities between the cases (a ballistics report had already confirmed that the same type of gun was used in both killings.)10 The suspects, however, remained at large.

Continued Intimidation

The killings of Phoung Sophat and Thon Phally proved to be just the start of an apparent intimidation campaign against opposition members in Sralop commune, and Funcinpec candidates in particular. About ten days after the killing, two men in military uniforms arrived after dark at the house of a prominent Funcinpec candidate in a village near Trapeing Dom. Armed with a handgun, an AK-47 automatic rifle and a flashlight, they called for him to come out, but he was not at home. His wife did not dare to open the door or look more closely at the men. The date of this incident is not confirmed, but it appears to coincide with the issue of warrants against Yuon Samoeun, Yuon Thonny and Chorn Rotha.

Five days later, two armed men matching the descriptions of those who had appeared at Trapeing Dom came to the house of another Funcinpec candidate. They did not enter the compound, but stood outside for around half an hour playing a flashlight over the house. They then moved down the road to repeat the intimidation at the house of another candidate. Five days later they returned, and the same pattern ensued.

Acts of intimidation returned to the village of Trapeing Dom, where Thon Phally had been murdered, targeting Funcinpec candidate Sin Suon, and his neighbor, party agent Pin Kha. On the night of December 13, two or three men entered Sin Suon's compound, kicking the ladder up to his house and threatening to release his cows. This was repeated a further four times, followed by visits on two occasions to the house of Pin Kha, until human rights workers visited Sralop on January 15 and learnt what was taking place. The following day, Sin Suon was evacuated from Sralop.

Prior to his evacuation Sin Suon and several other candidates in Sralop had taken to sleeping in the rice fields away from their houses, fearing that they might be killed if they could be found at night. By the time the official election campaign started on January 18, the party had arranged for all candidates to stay together in the Funcinpec commune office. This provided some safety in numbers, but the fact that the office was located directly opposite the Sralop police post, whose deputy chief was a suspect in the Thon Phally murder, did little to help the mood of the candidates. Funcinpec could not afford to extend this protection to other party members and agents.

On January 22, prominent Funcinpec figures came to campaign in Trapeing Dom, including Interior Co-Minister You Hokry and Kompong Cham First Deputy Governor Thav Kimlong. The visit may have provided the impetus for further political intimidation in Trapeing Dom that same night. Sin Suon was not at home, but his neighbor Pin Kha was targeted. On this occasion, villagers spotted men approaching from the fields and warned Pin Kha, who hid. A call was placed to the Sralop police post for assistance, but the villagers were told that no-one could come as all the policemen were "at a wedding". The police later denied this, saying they had sent an officer to the village, although he did not attempt to contact the victim or village authorities. Human rights groups assisted Pin Kha to join the Funcinpec candidates in the commune office for the remainder of the campaign.

The Official Response

As the election neared, human rights groups kept up pressure on the district court and the police to apprehend the murder suspects. The media also became alerted to the continuing problems in Sralop, and eventually the authorities began to act.

On January 11, 2002, the opposition newspaper Samleng Yuvachan Khmer (Voice of Khmer Youth) published an article on Tbong Khmum, describing the killings of Thon Phally and Phoung Sophat, the subsequent intimidation campaign and other violations taking place in the district.11 The following day, Director of National Police Hok Lundy issued an order suspending Seth and Veth to facilitate investigation into the Thon Phally case. The two policemen were required to reside in the district police headquarters - allowed to come and go freely, but not to return to Tbong Khmum.

On January 15, the Cambodia Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights (COHCHR) released a pre-election report that drew particular attention to two Cambodian districts, Tbong Khmum and Chhouk district in Kampot province:

It is the view of the Special Representative of the Secretary General for Human Rights in Cambodia that immediate steps should be taken in these locales and in surrounding areas to address practices that clearly contravene Cambodia's electoral and criminal laws, and to tackle longstanding problems arising from impunity12.

The focus drawn to the case by the U.N. and other human rights organizations appears to have been effective. Just two days after the report was published, Prime Minister Hun Sen spoke at the groundbreaking ceremony for a road reconstruction project in Tbong Khmum. Toward the end of a speech that focused on the importance of development assistance, he included a surprise announcement:

There is a murder case in the village of Sanlob, Sanlob commune. May General Choeun Sovantha search the two suspects as His Excellency You Hokry already passed the case down the system here.13 I gave my instruction days ago to arrest and bring these criminals to justice. Anyone [who] committed acts of violence must be arrested no matter what political party they belong to or ranks they may have.14

This direct order produced instant results. General Chouen Sovantha, the Commander of Military Region 2 and, according to some observers, the most powerful man in Kompong Cham, is an old ally of Hun Sen who fought alongside him against the Khmer Rouge. On January 18, Sovantha issued a directive for the arrest of Yuon Samoeun, Yuon Thonny and Chorn Rotha, citing the arrest warrants and Hun Sen's order. On January 29, Youn Samoeun was arrested in Phnom Penh. He denies involvement in the killings, and the other two men remain at large.

Human rights organizations continued their pressure on the Kompong Cham provincial court to prepare arrest warrants against the policemen known as Veth and Seth, and on February 22 the provincial prosecutor filed charges against them. On March 4, the two were finally placed in detention.

Wider Pattern of Violence in Tbong Khmum

Tbong Khmum has a long history of crime and violence, but a sharp increase in armed robberies in early 2002 with close similarities to the events in Sralop led human rights groups to question whether some of the same perpetrators - or organizers - might be involved. And whatever the true motivations behind the various attacks, they clearly served to heighten the atmosphere of fear and intimidation in the pre-election period.

On January 8, 2002, a group of four men in military uniform with flashlights and AK-47 rifles attacked the house of Heng Seng in Doung Preas village, An Cheum commune, beating his wife and stealing their valuables. Four days later the attackers returned to the village in greater numbers (witnesses put the group at more than six) and repeated the attack, first at the house of Heng Seng's sister, Heng Thol, and then at the adjacent house of their father, Doung Heng. Shots were fired at Doung Heng, who fled into the fields and is now believed to be in hiding with his family. The motive for the attacks remains unclear, but Doung Heng was clearly the target - the perpetrators named him during both attacks on his children. A former member of Funcinpec, Doung Heng was rumored to be joining the Sam Rainsy Party. The local police attributed the attack to a personal dispute, yet the numbers involved and professionalism of the assaults make this an unlikely scenario.

On the night of January 13, two near-identical armed robberies took place in villages some thirty minutes apart by road. In Suong commune, approximately five men with AK-47s and flashlights stole five buffalo from a house in Chrok Phaun village, on the edge of a rubber plantation. There was no attempt to conduct the robbery by stealth - the men deliberately awoke their victims, told them to stay inside and fired warning shots into the ground. Tracks indicated that the buffalo were led to a waiting truck in the plantation. Meanwhile, in Chup commune, a half-dozen armed men stole six cows from a house in Toul Sambo village, this time firing warning shots through the house. Tracks again led into the nearby rubber plantation, where it is thought a truck collected the animals. The following night, Tip Nimith village in Kor commune was targeted, with the victim Ms. Hang Srieng, the number five candidate on the Sam Rainsy Party candidate list. Three armed perpetrators stole two cows, shot and injured Hang Sreing's son, and once more escaped into the rubber plantation.

The victims of these three robberies had in common their vulnerability. Their houses were relatively remote and located next to plantations, making for an easy escape with the livestock. But perhaps more significantly, none had any connection with the ruling party or local officials - giving them little chance of justice. Hang Srieng was described as the poorest person in her village, making robbery at her house the least profitable.

The apparent professionalism of these raids stood in contrast to a series of otherwise similar robberies in the south of Tbong Khmum. A series of three attempted cattle robberies in Steung Penh village, Chikor commune over the nights of January 13-15 suddenly intensified on the night of January 16, when a gang of approximately ten men armed with AK-47s and sporting head-mounted flashlights entered the village, shooting and injuring a villager and escaping with his two cows. The following night, about a dozen men entered Thnung village in Muong Riev commune (not far from Steung Penh), again with AK-47s and head-torches, surrounded a house and attempted to steal cows. Spotted by a neighbor, they first shot at his house, then threw a grenade through his window, killing his mother-in-law, wife and two daughters.

On this occasion, however, the perpetrators were not aware that two trucks of provincial police were in the village in advance of the electoral campaign that began the following day. Hearing the shots and explosions, the police approached the scene and a firefight ensued. One perpetrator was fatally injured, but told the police before dying that he came from just over the district line in Sangke village, O Reang Ov district. The following day, police arrested nine men in Sangke, three of whom (including the village chief) remain in custody.

The gang from Sangke appeared far more amateurish than the perpetrators in the previous examples. They seemed to have little local knowledge and planning, not even being aware of the large police presence awaiting their final attack. Yet they had clearly been organized and equipped with uniforms, weapons and head-torches (the last of these probably being the hardest items to find in Cambodia). These may have been opportunistic, copycat attacks, but some observers have speculated that they were deliberately arranged to distract attention away from the unfolding events in Sralop commune.

The Impact of Intimidation

The effects of violence and intimidation go far beyond the individuals targeted, or the village or commune where they live. News of the double killing in Sralop commune spread swiftly throughout Tbong Khmum, causing many opposition candidates and activists to fear for their safety if they continued with their work.

In neighboring An Cheum commune, the Funcinpec candidates experienced a relatively peaceful campaign, taking the occasional drunken threat in stride. But they were acutely aware of the problems experienced by their counterparts in Sralop, to the extent that some admitted they did not want to win the election. They claimed that after the 1993 national election, when Funcinpec won in their commune, most members had been the victims of robbery. They did not expect any different this time around:

If we win, it is election night that we are afraid of, after they have counted and the results are produced. If we are lucky, then when we wake up our cows will be gone. If we are unlucky then our lives will be gone.15

Sam Rainsy Party candidates were similarly afraid. An SRP candidate in An Cheum explained:

Of course many people know about [the killings in] Sralop. Afterwards, my family came to me and asked me to stop being a candidate for Sam Rainsy. They had heard that I might be killed. But I decided to stay.16

In other communes, candidates experienced specific threats and intimidation, and were acutely aware of the potential threats to their safety. Opposition candidates from both parties in Longieng commune, where murder suspect Veth served as deputy police chief had been repeatedly threatened by one of his subordinates. Eventually, the district Sam Rainsy Party office lodged a complaint with the district police, and the accused officer was summoned to the district police headquarters. However, as the candidates were terrified of the policeman in question, who claimed to possess a large supply of weapons including guns, grenades and land mines, they did not wish to see him punished for fear that they would then be subject to reprisals:

We hope that he will be educated, and not fired. When he learnt that he had to go to the district police headquarters, he went to the house of every Sam Rainsy Party candidate, armed with a hand grenade, and told them that he would kill them all if he lost his job.17

The Post-Election Period

The opposition candidates in Tbong Khmum need not have worried about winning. The CPP were victorious through the district, taking 56 percent of the vote (compared with 37 percent in the 1998 national elections) and retaining control of all the communes. Their victory was mainly at the expense of Funcinpec, whose share of the vote dropped from 41 percent to 24 percent. The Sam Rainsy Party made gains, increasing their share from 11 percent to 19 percent. It was a pattern largely reflected throughout the rest of the country.

Polling day itself in Tbong Khmum was relatively quiet, with no major incidents of violence or intimidation, although there was a significant presence of village and commune authorities around polling stations (and in some cases inside, in the form of CPP party agents). In Sralop commune, six seats were won by the CPP, three by Funcinpec and two by the Sam Rainsy Party.

Shortly after the election, reports from Sralop indicated that the brother of murder suspect and deputy police chief Seth, along with the chief and deputy chief of his village, were coercing villagers to provide alibis for both Seth and Veth in the murder of Thon Phally. Meanwhile, the election has not ended the violence and intimidation. On March 3, gunmen shot and seriously wounded a former SRP candidate in An Cheum commune. Several candidates who were previously targeted for nighttime visits have again reported the presence of armed men near their houses after dark. With three of the five murder suspects now in custody, and the others having fled the area, it appears that other perpetrators continue to operate with impunity, and may be seeking retribution for the arrest of their fellow gang members.

Conclusion

Although much of Cambodia did not experience the level of violence and intimidation associated with the national elections of 1993 and 1998, this was not the case for Tbong Khmum district. The deliberate killing of two opposition members, combined with a follow-up campaign of armed intimidation, was easily sufficient to make opposition candidates and supporters throughout the district fear for their lives. In a situation where some candidates preferred to lose the election for fear that victory would bring retribution, it is clear that democratic processes are unable to function.

The prime suspects are law enforcement and military officers who are closely associated with local authorities and the ruling CPP. In the Sralop double killing, sustained pressure on national authorities and local police officials led to the arrests of three suspected perpetrators. Yet it remains to be seen whether future court proceedings will guarantee a fair hearing for the accused, and justice for the

victims.

The early indications are not promising. On April 8, 2002, Thon Phally's widow Soy Tha received a letter from the Kampong Cham provincial court notifying her that a trial had been set for April 12 - just four days later. In a highly irregular procedure, the letter included a list of sixteen people that she was required to bring to the court as prosecution witnesses. Summoning prosecution witnesses is the responsibility of the court, not the victim's family, a point emphasized by the fact that some of the names on the list were not even known to her.

The day before the trial was due to take place, and following the intervention of several human rights groups, lawyers appointed to represent Soy Tha won a postponement of the trial (citing the fact that they had not yet received the relevant court papers). A new date for the hearing has yet to be announced.

For the people of Tbong Khmum, it is doubtful whether any outcome will prove satisfactory. Many in Sralop commune expressed fear that Veth and Seth might be released. One witness to events on November 14 who provided a statement to police said that, although not a political party member, should the two suspects return he would have to leave the area for his own safety. Yet if any suspects are convicted, citizens are similarly afraid of the retribution that might come from their associates remaining at large.

The only effective way to resolve these problems remains to end the impunity granted to perpetrators of human rights abuses. The violence and intimidation in Tbong Khmum will prove an important test case for Cambodian justice, and should continue to be closely monitored if it is not to join the long roll call of unresolved cases of political violence. Unless the Cambodian authorities demonstrate clearly and effectively their willingness to pursue the perpetrators of politically motivated abuses and bring them to justice, the prospects for free elections in 2003 and beyond look bleak.

6 Report on Monitoring Of Political Intimidation And Violence (28 June - 5 July 1998), Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General for Human Rights in Cambodia, July 1998.

7 Human Rights Watch interview with Tbong Khmum resident, January 22, 2002.

8 Lor Chandara, "Two Killings Not Political, Police Say," The Cambodia Daily, November 19, 2001.

9 See Bou Saroeun, "Fear still haunts Kampong Cham commune," Phnom Penh Post, March 15-28, 2002.

10 Technical and Scientific Police Department Report, November 20, 2001.

11 Sorya, "Many Murders East of Mekong River," Samleng Yuvachan Khmer (Voice of Khmer Youth) newspaper, January 11, 2002.

12 COHCHR, "Pre-campaign period report by the Special Representative of the U.N. Secretary General for Human Rights in Cambodia on crime and intimidation related to the commune elections," January 15, 2002.

13 Shortly after the killings, Funcinpec Co-Interior Minister You Hokry established an investigative commission, although it appears to have taken little action.

14 "Selected Comments to the Groundbreaking Ceremony to Rebuild the National Road 7, 17 January, 2002," Cambodia New Vision, Issue 48, January 2002. "Sanlob" is an alternative name for Sralop; although neither killing took place in Sralop village, Hun Sen was clearly referring to the Sralop commune murder cases.

15 Human Rights Watch interview with Funcinpec candidate for An Cheum commune council, January 23, 2002.

16 Human Rights Watch interview with SRP candidate for An Cheum commune council, February 21, 2002.

17 Human Rights Watch interview with SRP candidate for Longieng commune council, February 21, 2002.