Summary

Tanisha James (pseudonym), a 25-year-old mother of four, was arrested in January 2017 after her boyfriend called the police when they were fighting. Tanisha told us that this was her first arrest and she “fought back that once.” Her boyfriend was not arrested.

Three of her children (toddler son and infant twin babies) were present at her arrest and Oklahoma’s child welfare services agency (OKDHS) immediately became involved.

Tanisha needed around US$6,000 to secure her release from jail on bond (bail was set at $61,000) but she could not afford to pay. She spent nearly one month incarcerated at Oklahoma County Jail before she accepted a guilty plea offer to charges of domestic violence and obstructing an officer and received a five-year suspended sentence. She said she pleaded guilty because she wanted to get back to her children as soon as possible: “I was sick of being away from my kids. I was crying every day. … All I wanted to do was be around them.”

OKDHS initially allowed Tanisha’s children to stay with their paternal grandmother while she was incarcerated. But after Tanisha’s release, her children were taken into foster care.

More than a year later, Tanisha is still fighting to regain custody of her children by meeting requirements in her child welfare reunification plan (which sets out conditions Tanisha must correct and services she must receive). If she does not satisfy the conditions of reunification, her parental rights can be terminated. But Tanisha told us that she cannot afford to meet some of these requirements. She cannot afford a required psychological evaluation, 52 required domestic violence classes ($25 per class, $1,300 total), and child support she is ordered to pay monthly to the state while her young children remain in foster care. In addition to these costs, Tanisha said that parenting classes were offered between 1-3p.m. and conflicted with her schedule. She had been working part-time, making only $43 per day, but said she lost her job when she missed work to attend mandatory meetings with OKDHS. She is worried her children will ultimately be adopted: adoption is “my biggest concern. … I’m not letting my kids go.”

Tanisha also told us that she is required to pay $40 per month for probation supervision, which she has been unable to afford, and she owes the $900 she was billed for each day she was jailed (more than $30 per day for 30 days) as well as other fines, fees, and court costs. She told us, “They try to set it up so that I will fail.”

***

Every day in Oklahoma, women are arrested and incarcerated in local jails waiting—sometimes for weeks, months, a year, or more—for the disposition of their cases. Most of these women are mothers with minor children.

Drawing from more than 160 interviews with jailed and formerly jailed mothers, substitute caregivers, children, attorneys, service providers, advocates, jail officials, and child welfare employees, this report shows how pretrial detention can snowball into never-ending family separation as mothers navigate court systems and insurmountable financial burdens assessed by courts, jails, and child welfare services—like in Tanisha’s case.

While most women admitted to jails are accused of minor crimes, the consequences of pretrial incarceration can be devastating. This report finds that jailed mothers often feel an added, and unique, pressure to plead guilty so that they can return home to parent their children and resume their lives. These mothers face difficulties keeping in touch with their children due to restrictive jail visitation policies and costly telephone and video calls. Some risk losing custody of their children because they are not informed of, or transported to, key custody proceedings. Once released from jail, they are met with extensive fines, fees, and costs that can impede getting back on their feet and regaining custody of their children.

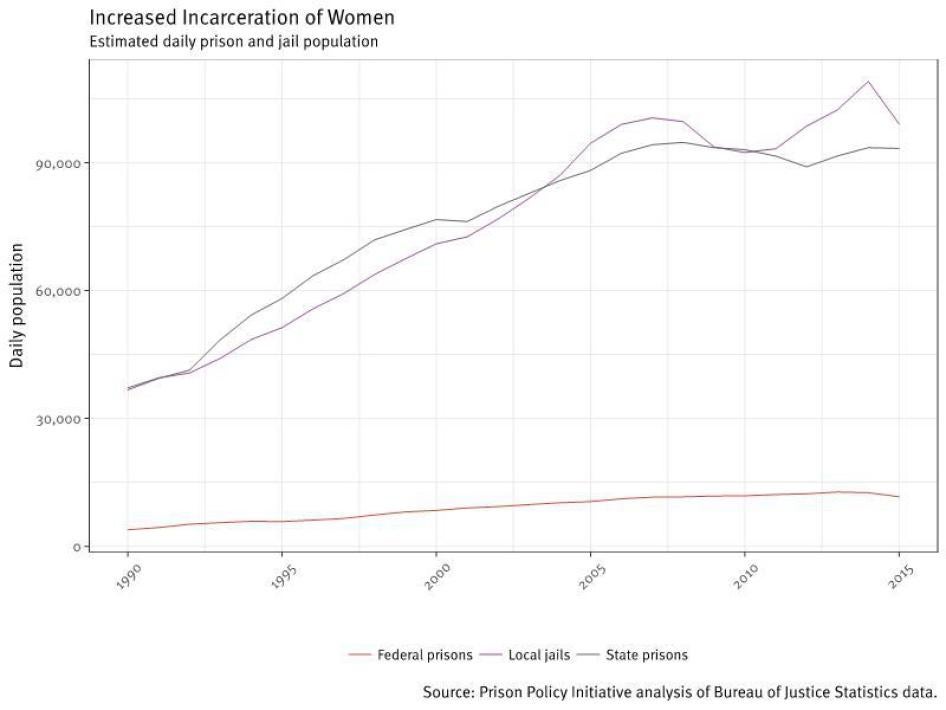

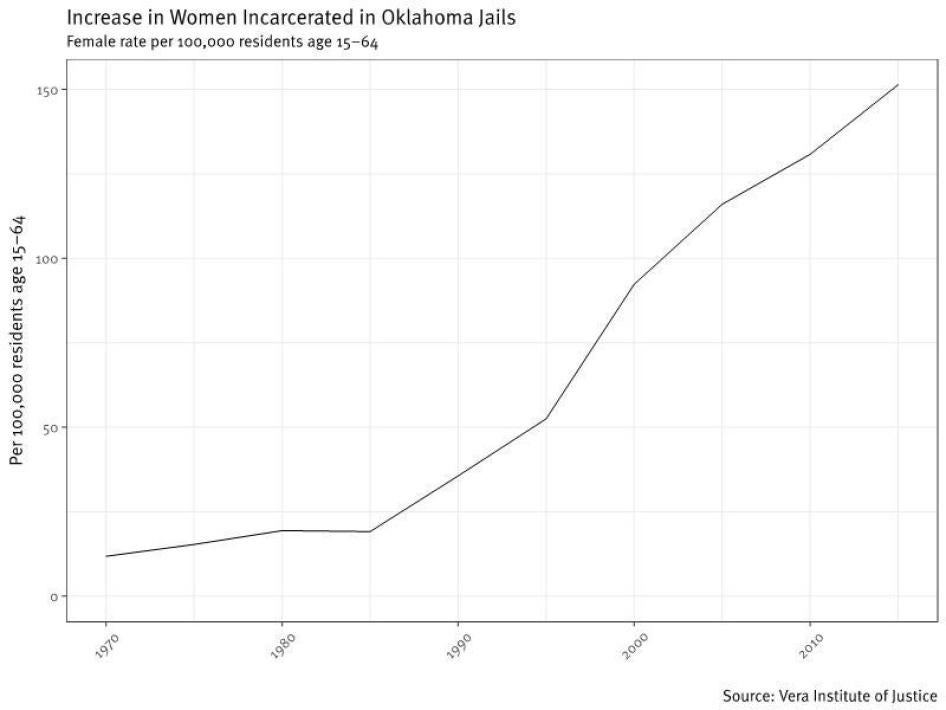

Women are the fastest growing correctional population nationwide and since the 1990s, Oklahoma has incarcerated more women per capita than any other US state.

Local jails (which typically house people prior to conviction, sentenced to short periods of incarceration, or awaiting transfer to prisons for longer sentences) are a major driver of that growth. On a single day, the number of women in jails across the US has increased from approximately 8,000 in 1970 to nearly 110,000 in 2014, a 1,275 percent increase, with rural counties accounting for the largest growth rate. Many times more are admitted to jail over the course of a year.

The growth in women’s incarceration also means growth in the number of jailed mothers, which has doubled since 1991. Nationwide, more than 60 percent of women in prisons and nearly 80 percent of women in jails are mothers with minor children. A study conducted by the US Bureau of Justice Statistics reported that a majority of incarcerated mothers lived with and were the sole or primary caretaker of minor children prior to their incarceration. This means that when mothers go to jail or prison, their children are more likely not to have a parent left at home, and can either end up with other relatives or in foster care.

One in 14 children in the US, or nearly six million children, have had a parent behind bars, which researchers identify as an adverse childhood experience associated with negative health and development outcomes. Children of color are disproportionately impacted by parental incarceration, with one in 9 Black children having had an incarcerated parent compared to one in 17 white children.

Jailed mothers are often dealing with a myriad of issues prior to their incarceration, which is why comprehensive support is essential to keep families together, disrupt cycles of incarceration, and to preserve human rights to liberty, due process, equal protection, and family unity. Losing contact with and custody of their minor children should not be a consequence of arrest and criminal prosecution.

While nationally and in Oklahoma the rate of women’s incarceration is garnering increasing attention, many barriers to achieving necessary reforms remain.

Human Rights Watch and the ACLU urge Oklahoma and other states to require the consideration of a defendant’s caretaker status in bail and sentencing proceedings, expand alternatives to incarceration, facilitate the involvement of incarcerated parents in their children’s lives and proceedings related to child custody, and substantially curb the imposition of fees and costs, which can impede reentry and parent-child reunification.

Money Bail, Pretrial Incarceration, and Added Pressure to Plead Guilty

Money bail in Oklahoma is not tailored to a person’s ability a pay and other individualized circumstances, including primary caretaker status, are not meaningfully considered. Public defenders told us that some judges in the state rely on preset bail schedules instead of conducting an individualized bail determination. If someone cannot afford to pay for their release, they are often stuck behind bars until case disposition. Being incarcerated in jail awaiting trial creates an enormous pressure to plead guilty and can result in worsened case outcomes. Nationally, it is generally true that prosecutors have overbearing influence over case outcomes and overcrowded and unsanitary jail conditions coupled with slow moving court systems can result in individuals accepting a guilty plea offer just so that they can get out of jail. Public defenders in Oklahoma also told us that their clients often wait 30 days before they can go before a judge with appointed counsel, including cases where the charges may only carry a maximum 30-day custodial sentence.

The pressure to accept a guilty plea is especially acute for jailed mothers who need to return home to parent their children. They also may reasonably fear the temporary or permanent loss of child custody. Several mothers we spoke with told us that they accepted guilty pleas, even when they would have otherwise wanted to fight their charges, because they needed to care for their children and they were afraid of losing child custody.

Parent-Child Communication While in Jail

Jails are meant to house people short-term and are ill equipped to meet the needs of incarcerated mothers and their children, especially those waiting months in jails for their cases to be resolved.

Although studies have shown the importance of maintaining contact with family to reducing recidivism rates, jail visitation policies in Oklahoma often bar or limit parent-child visitation and many jails have eliminated in-person visitation altogether. When in-person visitation is permitted, it is almost always behind a glass partition and mothers cannot touch and console their children.

The costs of telephone calls and video visitation can also be prohibitive, resulting in lapses in communication between mother and child. Some mothers we interviewed told us that they did not have any contact with their children and did not know where their children were located while they were in jail.

Child Custody and Parental Rights at Risk

When mothers are jailed, children are often placed either in the custody of non-parent family members or the state. If the state is involved, federal and Oklahoma law impose reunification deadlines: child welfare services must move for termination of parental rights if children are in foster care for 15 of the preceding 22 months, with only a few exceptions. Some states, including Oklahoma, expedite this timeline when a child is under four years old.

Mothers also may be closed out of key child custody-related decisions while they are in jail. Oklahoma law and policy require notice prior to family and juvenile court hearings but are vague about the jails’ responsibility to ensure jailed parents are transported to such proceedings. Law and policy are also vague about the required communication between jailed parents and child welfare caseworkers. Jail policies limiting visits and communication by telephone may exacerbate the difficulties mothers experience in staying informed about the custody and placement of their children. One mother told us that she did not discover she had lost child custody of one of her children until after her release from jail.

Additionally, lack of coordination with pregnant women and their families can result in a child, once born, being automatically placed in child welfare custody until a family member is approved as an appropriate guardian.

System Imposed Debt and Collateral Consequences

When mothers are released from Oklahoma jails, often after accepting a guilty plea, their struggles do not end. Some leave Oklahoma’s jails with a bill for the time they spent behind bars (“jail stay fees”), medical expenses they accrued during their jail stay, and fines, fees, and court costs that may be exorbitant. If they are on probation, supervision fees and onerous and costly conditions of probation can land them right back in jail. If their driver’s license is suspended or revoked, many face high costs to reinstate it. Without reliable access to public transportation, they face difficulties getting to work, school, doctor’s appointments, parenting classes, or other important destinations. When attempting to regain custody of children in the state’s care, costs can also accumulate for psychological evaluations, mandated drug testing, and child support.

These fines, fees, and costs can easily add up to thousands of dollars. Having a criminal record also results in formal and informal barriers to employment, housing, education, public benefits, and even child custody. In sum, these consequences of a criminal record exacerbate the instability facing mothers and their children.

Recommendations

Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union offer the following recommendations to improve outcomes for arrested mothers and their children. Other broader criminal justice reforms would help to address the problems identified in this report, including:

- More and better-resourced alternatives to arrest, prosecution, and incarceration.

- Wholesale reforms to eliminate reliance upon bond schedules, eliminate or substantially reduce the imposition of money bail, and the establishment of a strong presumption for nonmonetary release.

- Amendments to mandatory minimum sentencing laws, reductions to sentencing ranges and sentencing enhancements, and an end to hard-line restrictions on early release from prison.

- Wholesale reforms to substantially reduce criminal justice fines and eliminate fees and court costs.

- Decriminalization of drug possession for personal use and expanded access to evidence-based treatment and support, including harm reduction services.

- Retroactive criminal justice reforms to ensure fairness and proportionality.

To Oklahoma Lawmakers

- Enact primary caretaker legislation that would require judges to consider a defendant’s primary caretaker status: (1) when making bail determinations; (2) when deciding to revoke a suspended sentence or accelerate a deferred sentence; and (3) at sentencing. At sentencing, and where warranted, primary caretakers should receive a community-based alternative to incarceration in lieu of a custodial sentence.

- Enact legislation that would eliminate the use of bond schedules and require individualized bail determinations that take into account primary caretaker status, ability to pay, and other mitigating factors.

- Enact legislation to provide mothers who give birth under the supervision of jails and prisons with substantial time to spend with their newborns, mandate full access to menstrual and other hygiene products at no cost, and require the provision of holistic prenatal, postpartum, and other healthcare at no cost.

- Appropriate funds to expand programs and services available to parents in jails and prisons, including programs and services that will satisfy conditions laid out in a child welfare reunification plan.

- Enact legislation that substantially reduces court fines and eliminates fees and court costs. In the alternative, require the consideration of primary caregiver status when decisions are made to reduce fines, fees, and court costs or to set up reasonable payment plans.

- Appropriate funding to OKDHS or external service providers to assist parents who are unable to afford the fees required to access services required under a child welfare reunification plan.

- Appropriate funds to expand programs and financial assistance for substitute caretakers of minor children.

- Enact legislation that creates a clear statutory obligation on courts to notify jailed parents of all family and juvenile court proceedings through personal service and to order the transport of incarcerated parents to all such proceedings.

- Enact legislation that requires OKDHS caseworkers to communicate directly with incarcerated parents as frequently as necessary to ensure parents are informed of their children’s condition and whereabouts and informed of all custody-related meetings and proceedings.

- Enact legislation that requires an inquiry into a jailed parent’s ability to access and pay for courses, drug testing, and related programs before such requirements are included in a child welfare reunification plan.

- Enact legislation that requires jail officials to inquire about and track the parenting status of newly admitted people.

- Enact legislation that would require the regular collection and publication of data that can be disaggregated (by gender, race, and ethnicity) about the number of jailed people, their primary caretaker status, and their children’s living arrangements.

To Oklahoma Judges

To the extent permitted by law and by limits on the appropriate exercise of discretion:

- Consider primary caretaker status, ability to pay, and other mitigating factors: (1) when making pretrial release decisions by prioritizing nonmonetary pretrial release; (2) when making sentencing decisions by prioritizing alternatives to incarceration and restricting onerous conditions of a noncustodial sentence, including eliminating or reducing the imposition of financial contributions from a person sentenced; (3) when deciding to revoke a suspended sentence or accelerate a deferred sentence by prioritizing continued release; and (4) when imposing fines, fees, and court costs by opting to not impose such fees and costs.

- Order regular in-person physical contact visitation between a child and their incarcerated parent. Judges should also coordinate visits between jailed parents and their children before or after family or juvenile court hearings.

- Ensure sufficient notice and issue court orders to transport incarcerated parents from jails and prisons to custody or juvenile court hearings, including by writ if a parent is jailed in another county.

To Oklahoma Prosecutors

To the extent permitted by law and by limits on the appropriate exercise of discretion:

- Consider an accused person’s primary caregiver status: (1) before deciding to pursue charges; (2) before arguing against pretrial release by ensuring the least restrictive means of release; (3) when making plea offers and sentencing recommendations by prioritizing alternatives to incarceration and by not seeking onerous conditions of a noncustodial sentence, including financial contributions from a person sentenced; and (4) before filing applications to accelerate deferred sentences or to revoke suspended sentences.

- Consider barriers to reentry for formerly incarcerated parents and its effect on child welfare reunification plan compliance prior to moving to terminate parental rights (TPR) in juvenile court.

To the Oklahoma Department of Human Services (OKDHS)

- Coordinate regular in-person physical contact visitation between parent and child while a parent is incarcerated in jails and prisons.

- Certify programs or develop evidence-based and culturally competent curricula to be used in jails and prisons that parents can enroll in to satisfy child welfare reunification plan requirements while incarcerated.

- Ensure regular communication between OKDHS caseworkers and parents about the status of children in the state’s care, including the child’s placement, reunification goals, and available services during incarceration and upon release.

- Implement or expand training for OKDHS staff on best practices in supporting incarcerated and formerly incarcerated parents and their minor children.

- Revise OKDHS policies to clarify communication requirements between caseworkers and jailed parents.

- Regularly collect and publish data that can be disaggregated (by gender, race, and ethnicity) on temporary removals, TPR, and the number of children in child welfare custody with an incarcerated or formerly incarcerated parent.

To Oklahoma Jail Administrators

- Expand visitation policies to include regular in-person physical contact visits between jailed parents and their minor children and coordinate with OKDHS and courts to facilitate visitation.

- Provide access to free weekly telephone calls between indigent jailed parents and their children, child welfare caseworkers, and custody or juvenile court attorneys.

- Ensure that jail security levels do not prohibit access to parent-child visitation and enrollment in parenting courses or other courses or services available that satisfy child welfare reunification plan requirements.

- Ensure the distribution of adequate menstrual and other hygiene products at no cost.

- Ensure coordination with family and juvenile court to facilitate transportation of jailed parents to all court proceedings.

- Track the primary caretaker status of those admitted to jails.

To the United States Government

To the Congress of the United States

- Pass legislation to ensure access to adequate menstrual and other hygiene products and prenatal and postpartum care inside jails and prisons.

- Pass legislation to provide targeted support to children with incarcerated parents, reunification services for incarcerated parents, and financial assistance and other resources to family caregivers.

To the US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics

- Regularly collect and publish data that can be disaggregated (by gender, race, ethnicity, and caregiver status) on the jail population nationwide.

- Update and publish the “Parents in Prison and Their Minor Children” study, including the jail population.

To the US Department of Health and Human Services

- Establish pilot programs designed specifically to ensure in-person physical contact between incarcerated parents and their children and to reunify formerly incarcerated parents with their children in foster care.

- Regularly collect and publish data that can be disaggregated (by gender, race, and ethnicity) on the number of children in child welfare custody with a current or formerly incarcerated parent.

Methodology

This report is the product of a joint initiative—the Aryeh Neier fellowship—between Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union to strengthen respect for human rights in the United States.

The report is based on 163 in-person and telephone interviews[1] conducted primarily between October 2017 and July 2018, as well as extensive desk research and analysis of publicly available information and data, policies, and procedures provided to Human Rights Watch in response to public information requests.

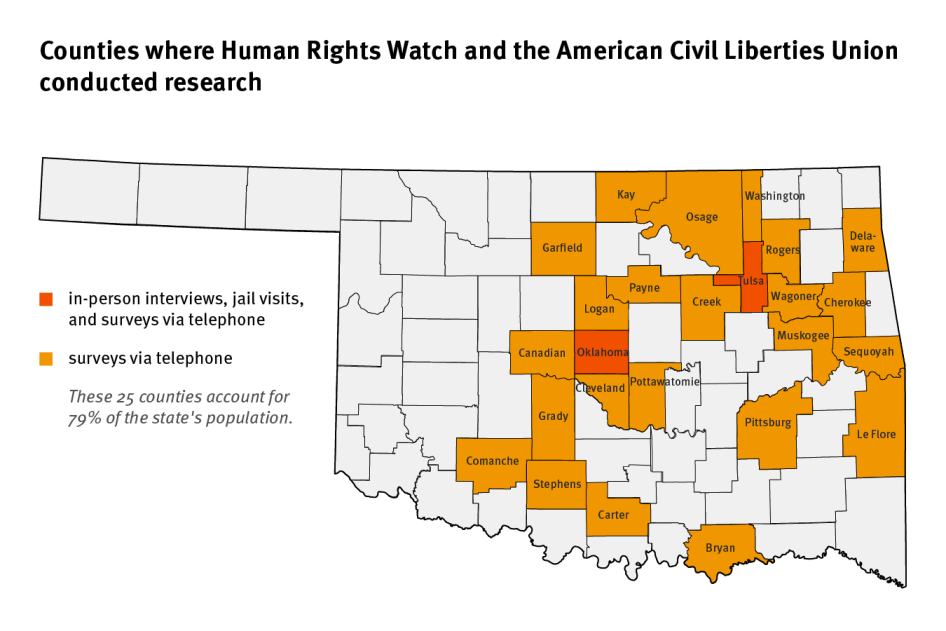

We conducted interviews with 35 women who had minor children while incarcerated pretrial in Oklahoma county-run jails. Human Rights Watch identified individuals through outreach to local service providers, defense attorneys, and advocacy organizations. Most of our interviews with incarcerated and formerly incarcerated mothers were conducted in Oklahoma at the site of diversion programs in Tulsa County and Oklahoma County or at Tulsa County Jail. Most interviews inside Tulsa County Jail were conducted individually, in a meeting room, and in the presence of a clinician.[2]

Nearly all of the mothers we interviewed for this report were current participants or alumni of diversion programs in Tulsa County and Oklahoma County, or current participants in the Parenting in Jail Program at Tulsa County Jail. Women in these programs are mostly mothers with histories of substance dependence. Most of the mothers we interviewed also had extensive criminal records that they often attributed to trauma, poverty, and substance dependence.

All individuals interviewed provided verbal informed consent and no incentive or remuneration was offered to interviewees. The researcher informed potential interviewees that they were under no obligation to speak with us and that they could decline to answer questions at any point or terminate the interview at any time. The researcher also informed interviewees of the purpose of our research and our intention to publish a report. We did not ask questions about disputed facts or issues related to their underlying criminal charges, especially in cases where charges were still pending.

Out of concern for the privacy of mothers and their families and given the sensitive nature of the information they provided, we have chosen to use pseudonyms in all cases, with the exception of two formerly jailed mothers with their permission. In one instance, we have not used the name of a non-profit attorney, at her request. In such cases, we have noted our use of pseudonyms or our decision to withhold a name in the relevant citations.

We conducted interviews with 118 caregivers, children, attorneys, service providers (including those working for non-profit organizations and diversion and reentry programs), government workers (including judges, pretrial services, jail staff, and child welfare (OKDHS) employees), as well as local and national advocates to understand the unique challenges facing incarcerated mothers and the effect of maternal incarceration on children and families.[3]

In some cases, we reviewed individual records of fines and fees imposed on convicted mothers, child support and reunification-related fee schedules, and, where available, relevant state court records on the cases we describe.

Human Rights Watch submitted data requests regarding the correctional population, personal demographics of incarcerated persons (including race, gender, and parental status), charges and sentences, bail status (including amount), entry and release dates, and primary caregiver, marital, and pregnancy status to jail public information officers and clerks of courts in Tulsa County and Oklahoma County, the two largest counties in the state. We also requested policies and procedures related to visitation and mother-child separation for women giving birth while detained. We received responsive data from Tulsa County Jail.

Although most of the women we interviewed were incarcerated in jails in Tulsa County and Oklahoma County and data requests were submitted only to these counties, some had been incarcerated in other county jails, including jails in other urban and rural counties.

Human Rights Watch also surveyed jail visitation policies, incarceration-related costs, and programming availability in the 25 most populated counties in Oklahoma. We consulted jail websites, made several calls to jails directly, and attempted to gather information from private company websites (who contract with jails to provide medical care or video and telephone service). Some jail staff refused to provide information via telephone or did not know the answers to questions we asked, leading to gaps in the information collected. We also received conflicting information. In these cases, we relied on information provided during our most recent call to each jail.

The exact number of incarcerated parents nationally, and in Oklahoma, is not known. Nationwide jail data is limited, dated, and often not disaggregated by gender, parental status, and jurisdiction, making it impossible to obtain comprehensive figures or even reliable estimates of the parental status of women and girls admitted into local jails and prisons each year. Similarly, the Oklahoma data presented in this report is necessarily limited because parental status is not systematically tracked or published.

While this report focuses on Oklahoma, we draw extensively on publicly available national data from the US Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics and Bureau of Justice Assistance, US Department of Health and Human Services’ Administration for Children and Families Children’s Bureau, and the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Kids Count Data Center.

A note on terminology:

Throughout the report, we use phrases such as “jailed” or “formerly jailed” mother and “person living with substance dependence” to avoid stigmatizing language. Quotes from interviewees or other sources have not been altered to conform to the language choices elsewhere in this report.

The term “jail” refers to county-run facilities that typically incarcerate people who are awaiting trial, awaiting transfer to another jurisdiction, sentenced to shorter terms of incarceration (usually one year or less), or sentenced and awaiting transfer to prison.

In Oklahoma, Child Welfare Services, Child Protective Services, and Child Support Services are under the Oklahoma Department of Human Services (OKDHS). In this report we may use “child welfare services,” “child welfare system,” and “OKDHS” interchangeably to refer to these Oklahoma systems.

We also use the term “individualized service plan (ISP)” and “reunification plan” interchangeably to describe the requirements set forth by OKDHS and the juvenile court that a parent must satisfy in order to reunify with their children. A reference to the termination of parental rights is also abbreviated as TPR.

Lastly, the terms “caretaker” and “caregiver” may be used interchangeably to describe an individual’s role in providing care to minor children, adults with disabilities, and older persons. We also use the term “substitute caregiver” to describe non-parent caretakers of children with an incarcerated parent during the parent’s incarceration, primarily in reference to kinship caregivers.

I. Background

A National Problem: Disproportionate Rise in Women’s Incarceration

Approximately 219,000 women and girls are incarcerated in the US.[4] While women account for just 14 to 15 percent of the US jail population[5] and 7 percent of the state and federal prison populations,[6] for nearly four decades, women have been America’s fastest growing correctional population.[7]

Recent efforts to curb mass incarceration impact women and men differently. The Prison Policy Initiative has reported that in 35 states, women’s state prison incarceration has “fared worse” than men’s because the population of women in prisons has either (1) grown while the population of men in prison has declined, (2) outpaced growth in men’s prison population, or (3) declined at a lesser rate than the population of men in prison.[8]

Like men of color, women of color are overrepresented in US prisons and jails. The incarceration rate of Black women and Latinas is 2 times and 1.4 times, respectively, the incarceration rate of white women.[9] The race, ethnicity, and gender of the US jail population has not been tracked and published in nearly 20 years,[10] however, the most recent data available reported that women of color accounted for nearly two-thirds of the women’s jail population—Black women accounted for 44 percent, Latinas accounted for 15 percent, and “other” women of color accounted for 5 percent.[11]

Drivers of Women’s Incarceration

Women’s pathways into the criminal justice system are unique. Studies have found that a majority of incarcerated women have significant histories of substance dependence, physical ailments, mental illness, intimate partner violence, homelessness, and joblessness.[12]

US Bureau of Justice Statistics studies have found that, compared to jailed men, more women in jails reported having a medical problem (53 percent compared to 35 percent),[13] mental impairments (15 percent compared to 7 percent),[14] and mental health problems (75 percent compared to 63 percent).[15]

A multi-site study of rural and urban jails in the US also found that a majority of women had experienced violence:

- 86 percent had experienced sexual violence in their lifetime;

- 82 percent of jailed women met criteria for drug or alcohol dependence;

- 77 percent had survived intimate partner violence;

- 73 percent had witnessed violence;

- 63 percent had been subjected to non-familial violence; and

- 60 percent had experienced caregiver violence.[16]

Efforts to cope with trauma and defend[17] against violence can lead to incarceration, and incarceration is likely to worsen the psychological impact of pre-existing traumas.[18] The American Civil Liberties Union has also previously documented the ways in which women are funneled into jails and prisons for tangential involvement in crimes under conspiracy and accomplice liability theories.[19]

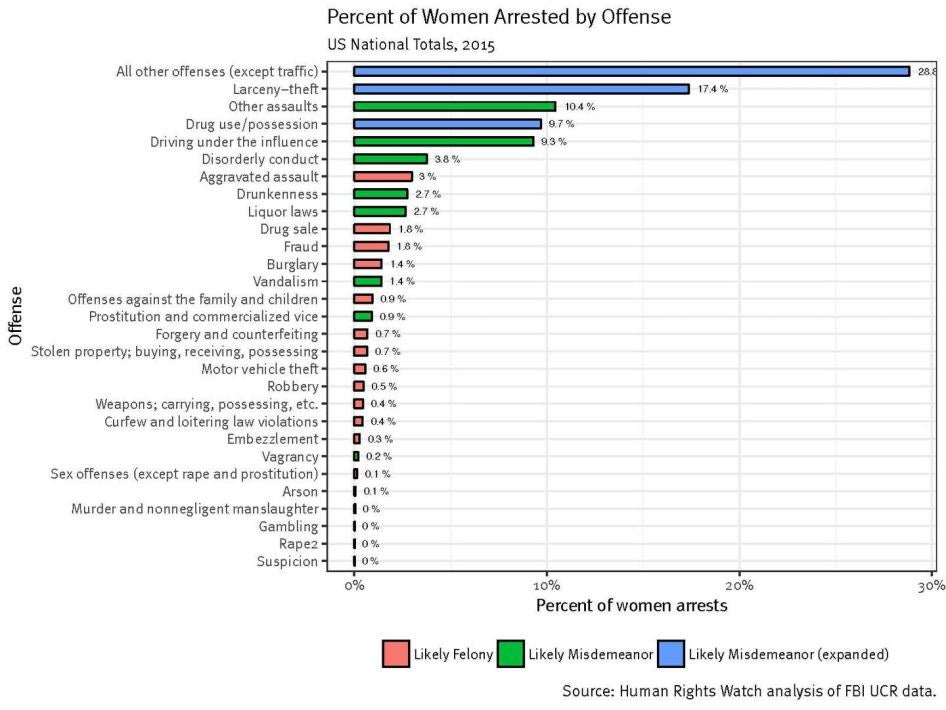

Moreover, women are more likely to be jailed (detained before trial or sentenced) for nonviolent offenses than men (82.9 percent compared to 73.5 percent),[20] are more likely to serve their first sentence (48.7 percent compared to 36.8 percent),[21] and are somewhat more likely to be “nonviolent recidivists” (35.3 percent compared to 33.3 percent), according to national data from 2002.[22]

Our analysis of national data on women’s arrests also show most women are charged with offenses that are likely misdemeanors:[23]

Mirroring national data, most of the women we spoke with in Oklahoma had criminal records resulting from long-term substance dependence and poverty and were met with harsh punishment. As one mother told us:

Throughout the off and on almost 20 years of my addiction, most of my arrests were drug related. Some of them may have not been [a] drug charge. I may not have had drugs on me, but I was charged with petty larceny because I was stealing from stores. Some of the time it probably was to feed my addiction, but for the majority of them, I did whatever I needed to do to feed my children. To clothe my children. … Diapers. … To get money for items to be able to afford a hotel room for the night because we were living out of my van at some point. I always wanted to make sure that we had a hotel room to sleep in. The cycle would start all over again the next day.[24]

Another mother told us, “If you’re a single parent, sometimes you gotta do what you gotta do.”[25]

Growth in Women’s Jail Population

Jails are a major driver of women’s incarceration in the US. Just 40 years ago, about three-fourths of county jails in the US did not house any women—now, nearly all jails house women.[26] The number of women in jails on a single day has increased from approximately 8,000 in 1970 to nearly 110,000 in 2014, a 1,275 percent increase.[27] The growth has been highest in rural counties, where the rate of women in jail has increased from 79 to 140 per 100,000 between 1970 and 2014.[28]

Yet the daily population count obscures the high number of jail admissions. Over the course of a year, approximately 1.5 million women are admitted to jail.[29] And over the past 15 years, 99 percent of jail growth has been a product of pretrial incarceration.[30] Sixty percent of women in jail have not been convicted of a crime and are awaiting trial.[31] Incarcerated women are also almost equally dispersed between local jails and state prisons, while twice as many incarcerated men are in state prisons than in local jails.[32]

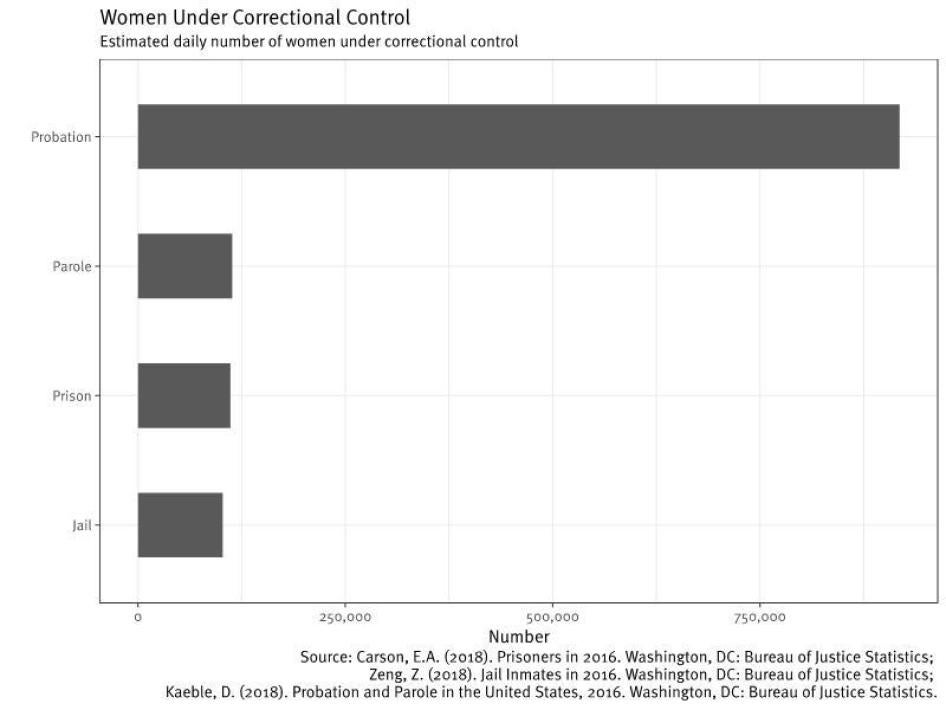

Women Under Correctional Control

3,673,100, or approximately one in 68 adults in the US, were on probation (period of supervision in the community, typically imposed as an alternative to incarceration) at the end of 2016.[33] The majority (55 percent) of adults in contact with the criminal justice system are on probation—for women, nearly 75 percent are on probation.[34]

While probation is a less severe sentence than incarceration because it is served in the community, conditions to satisfy probation are often onerous, cost-prohibitive, and long lasting and failure to comply with those conditions can result in imprisonment.[35]

In addition to probation, diversion programs can be used as an alternative to a custodial sentence. In Oklahoma, diversion programs specifically for women are available in Tulsa County and Oklahoma County and these programs aim to provide holistic services and reunite women with their children.[36] However, some women wait months in jail before they are referred to a diversion program,[37] women in other counties do not have access to similar programs,[38] and failure to comply with the requirements of a diversion program can also result in imprisonment.

Some states in the US have introduced primary caretaker legislation that requires a defendant’s primary caretaker status be taken into account at sentencing to divert convicted parents from prison to an alternative to incarceration.[39] Similar legislation should be introduced in Oklahoma to require the consideration of primary caretaker status[40] at every stage of the criminal justice system, including when conditions of pretrial release are set, when convicted individuals are sentenced, and when decisions are made to revoke probation or a suspended sentence[41] or to accelerate a deferred sentence.[42]

Women’s Incarceration in Oklahoma

Oklahoma has the highest incarceration rate in the country (1,559 per 100,000 adult residents)[43] and for decades has incarcerated more women per capita than any other state (159 per 100,000 women in prison,[44] 151 per 100,000 women in jail[45])—a rate that is more than double the national average.[46]

Research on women incarcerated in Oklahoma prisons has found that nearly two-thirds were first time offenders and most were in prison for nonviolent offenses, with more than half admitted into prison for a drug offense and nearly 20 percent for violations of probation or parole.[47]

A 2017 analysis of Oklahoma Department of Corrections data by Reveal found that Indigenous women are incarcerated at a rate three times higher than their proportion of the state’s total population.[48] For Black women, their rate of incarceration is twice as high as their proportion of the state’s total population.[49] Reveal also reported disparities in incarceration rates county-by-county, indicating that rural areas have higher incarceration rates.[50]

While new initiatives have and continue to be implemented in larger counties, these efforts must be extended to rural areas of the state. Without substantial and retroactive criminal justice reforms, the rate of people in prison in Oklahoma will only continue to grow. In 2017, it was estimated that by 2026, the number of women in prison would increase by 60 percent, compared to 30 percent overall in Oklahoma.[51]

Women Held in Oklahoma’s Jails

Oklahoma has 77 counties and each county has a county-run jail.[52] The Vera Incarceration Trends database reports that in 2015, 12,096 people were held in Oklahoma’s jails on any given day and over 281,000 were admitted over the course of the year.[53] Oklahoma’s jail incarceration rate is 46 percent higher than the average US state (478.3 per 100,000 compared to 327.2 per 100,000). The state’s pretrial jail incarceration rate is about 54 percent higher than the average state (322.2 per 100,000 compared to 209.8 per 100,000).[54]

According to Vera, in 1970, the pretrial incarceration rate for women in Oklahoma was 11.8 per 100,000 (95 women)—this rate swelled to 151.4 per 100,000 in 2015 (1,905 women):[55]

In 2016 and 2017, Vera published reports analyzing Oklahoma County and Tulsa County jail admissions for the previous year. Vera reported that more than 28,000 people were booked into Oklahoma County Jail in 2015 and estimated that 80 percent of the jail population was held pretrial.[56] Women accounted for 27 percent of jail admissions.[57] Black people accounted for 40 percent of the jail population, while only accounting for 15 percent of the total county population.[58]

In Tulsa County, Vera reported that more than 76 percent of the Tulsa County Jail population was held pretrial.[59] Vera also found that only 9 percent of people detained in Tulsa County Jail were convicted and serving their sentence in the jail.[60]

Human Rights Watch submitted requests to Tulsa County and Oklahoma County and we received responsive 2016-2017 jail admissions data from Tulsa County Jail.[61] Over the two-year period we analyzed, women accounted for about one-fourth (26.5 percent) of jail admissions—a total of 13,907 unique jail bookings and 9,013 women.[62] About 30 percent of women admitted in the jail were booked in more than once.[63]

Black women accounted for 25.3 percent of jail bookings,[64] which is more than double their population in the county.[65] White women accounted for 65.5 percent.[66]

Many women were booked into Tulsa County Jail for low-level offenses. The most common offenses women were charged with were:[67]

|

Top Charges for Women Booked into Tulsa County Jail |

||

|

Charge |

# of women booked in with charged offense |

Percentage of women booked in with charged offense |

|

No Proof of Liability Insurance |

1,604 |

12% |

|

Possession of Drug Paraphernalia |

1,480 |

11% |

|

Possession of Controlled Dangerous Substances |

1,434 |

11% |

|

Driving Under the Influence |

1,156 |

9% |

|

Failure to Pay Court Cost |

1,124 |

9% |

|

Application To Accelerate a Deferred Sentence |

1,097 |

8% |

|

Larceny - Merchandise - Retailer |

1,037 |

8% |

|

Application To Revoke a Suspended Sentence |

952 |

7% |

|

Suspended Or Revoked Driver’s License |

952 |

7% |

|

No Drivers License |

934 |

7% |

|

Improper License Plate Display/Expired Tag |

902 |

7% |

|

Drive Under Suspension |

753 |

6% |

Vera’s data analysis of Tulsa County Jail admissions found that Black women were admitted on municipal charges (typically jailed on warrants for traffic-related violations) at a rate 3.8 times higher than that of white women.[68]

Incarceration’s Impact on Children, Other Dependents, and Substitute Caregivers

Mothers in Jails and Prisons

Nationwide, more than 60 percent of women in prisons[69] and nearly 80 percent of women in jails are mothers with minor children.[70] Five percent of women admitted into jails are pregnant.[71]

One in 14 children in the US, or nearly six million children, have had a parent behind bars[72] and the number of children with an incarcerated mother has more than doubled since 1991.[73] Almost half of children with incarcerated parents are under 10 years of age.[74]

In Oklahoma, the percentage of children impacted by parental incarceration is greater than the national average.[75] According to the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Kids Count Data Center, 12 percent of children in Oklahoma (108,000 children) have a parent or guardian who has served time in jail, which is greater than many of its neighboring states including Texas (9 percent), Missouri (9 percent), Colorado (8 percent), and Kansas (9 percent).[76]

A Bureau of Justice Statistics study has shown that a majority of incarcerated mothers lived with and were the sole or primary caretaker to their minor children prior to their incarceration.[77] This means that when mothers go to jail or prison, their children are more likely to not have a parent left at home and are more likely to end up in foster care.[78]

Incarcerated Parents in State Prison and Their Minor Children

|

Child/Children’s Living Arrangements Prior to and During Parent’s Incarceration

|

Incarcerated Mothers |

Incarcerated Fathers |

|

Lived with child/children in the month prior to arrest |

55.3% |

35.5% |

|

Single parent household |

41.7% |

17.2% |

|

Provided daily care to child/children |

77% |

26% |

|

Child/children living with non-parent relatives during incarceration |

67.7% |

21.3% |

|

Child/children living with other parent during incarceration |

37% |

88.4% |

|

Child/children in foster care |

10.9% |

2.2% |

A 2014 study of women in Oklahoma prisons found that:

- 68 percent of women in prison had a minor child;

- The average woman had 2.4 minor children;

- The median child’s age was 7.6 years old;

- Two-thirds of mothers in prison were living with their minor children at the time of their arrest;

- Almost half of women living with their minor children were not living with a partner;

- Nearly 58 percent of minor children were now living with family or friends;

- 26 percent of minor children were now living with the other parent;

- Nearly 10 percent were living in foster homes or agencies;

- The average age of minor children in foster care was only 4.2 years old; and

- Nearly 12 percent of incarcerated mothers reported that they did not know where their children were located.[79]

A 2015 study found that children living in rural areas and children of color in the US are disproportionately impacted by parental incarceration, with one in 9 Black children having had an incarcerated parent compared to one in 16 Latino children, one in 14 children from other races, and one in 17 white children.[80]

Indigenous and Black children are also overrepresented in the foster care system.[81] Indigenous children make up 1 percent of the US population under 18[82] but accounted for 2 percent of children in foster care in 2016.[83] The foster care system’s proportion of Black children has radically declined in the past two decades, from 43 percent in 1998[84] to 23 percent in 2016,[85] but remains disproportionate, as Black children are just 14 percent of the US population under 18.[86] Data also shows that 8 percent of children in foster care in 2016 (20,939 children) were placed in state custody because of parental incarceration.[87]

Impact on Children

Parental incarceration can take a toll on the health and development of children and is identified by researchers as an adverse childhood experience.[88] Incarcerated mothers who have infants shortly before they are jailed or who give birth behind bars, are not given opportunities to bond with their babies.[89] This can cause attachment and development issues.[90]

National studies show that children with incarcerated parents are more likely than children without incarcerated parents to have poor peer relationships and exhibit emotional and psychological problems, as well as internalized and externalized behaviors (including aggression, hostility, eating disorders, and self-harm) later in life.[91] Studies also show that school-aged children with incarcerated parents often have diminished educational outcomes, such as poor grades and higher suspension and dropout rates.[92]

In the 2014 study of women in Oklahoma’s prisons, mentioned above, incarcerated mothers reported that their children experienced higher incidents of poor grades, problems with friends and guardians, expulsions from school, running away, depression, and suicidal ideation since their mother’s incarceration.[93]

The manager of a re-entry program that unites children with parents after they are released from Oklahoma’s prisons estimated that 80 percent of the kids she sees have abandonment, behavioral, or mental health issues, including several children who have experienced suicidal ideation.[94]

Two social workers in Oklahoma described the devastating impact of having an incarcerated parent on children. One said, “A lot of shame … gets transferred to the kids” and the children often do not know why their parent is away.[95] The other told us:

Instability at home creates a domino effect at school. … They feel like their parents don’t love them and are unable to focus. … They are bullied and because they are worried about keeping their heads above water, they can’t think about school. … It hurts when you have a loved one who is here one day and gone the next.[96]

One jailed mother of four told us that the father of her two oldest children (ages 18 and 14) died just one year before she was arrested.[97] She said that being incarcerated makes her children “feel like they lost both [of] their parents.”[98] Her younger children (6 and 4) have also been impacted—she told us that her 6 year old is not communicating and is overeating and her 4 year old “tells me all the time that he dreams about me being home.”[99]

When mothers are jailed, the home lives of their children are more likely to be disrupted. Jailed and formerly jailed mothers told us that their children changed homes and schools since their mother’s incarceration.[100] Some children were shuffled from one home to another, in foster care or with relatives, and sometimes they were separated from their siblings.[101] Some mothers also may not know where their children are located.[102]

April Weiss, a 30-year-old mother of three, told us, “I didn’t want my kids to be separated. When I was a kid, I was in foster care. It was the first traumatic experience of my life being separated from my younger siblings. Now my daughter only gets to see her sisters eight hours each month.”[103]

Intergenerational incarceration is also a major concern. About 26 percent of women responding to an Oklahoma prisons study reported growing up with a parent behind bars.[104] We also spoke with a few mothers who told us their parents, their children, or the fathers of their children had been incarcerated, and some expressed a strong desire to break the “vicious cycle.”[105]

Impact on Other Dependents

Women are also more likely to be caregivers to young people, older people, and people with disabilities.[106] Therefore, when women are incarcerated, they are likely to leave behind dependents other than their minor children who may not have other resources for care. While national and local data does not track the caregiver status of incarcerated people, a few mothers we spoke with told us that they were providing primary care to family members in addition to their children.

One mother told us that prior to being jailed at Tulsa County Jail for more than seven months, she was raising her then 2-year-old granddaughter and her three minor children (ages 17, 14, and 5).[107] Another mother said she was caring for her 2-year-old son, 82-year-old grandmother, and younger siblings before she was jailed at Tulsa County Jail for 10 months. She told us, “Everything I have done in my life revolves around [my son], other kids, and older folks. … Me being here hurts my family a lot because they don’t have me.”[108]

Impact on Substitute Caregivers

As noted above, children with incarcerated mothers are more likely than children with an incarcerated father to live with a grandparent or another relative while their mother is away.[109] The quality of caretaker relationships and meaningful contact with incarcerated parents make a significant difference in how well children weather the traumatic experience of being separated from their incarcerated parent.[110] However, substitute caretakers often struggle for lack of the financial and emotional support they need.[111] One mother told us that the guardian of her 2-year-old daughter “makes too much money” and has to pay US$900 per month for childcare out of pocket.[112]

We spoke with a jailed mother who told us, while in tears, that her cousin is taking care of her 2-year-old son. She said she does not want to burden her family and tells her 26-year-old cousin, “You have your own life.”[113]

For older persons, who may be unemployed, retired, and/or living on a fixed income, taking on the primary caretaker role of a minor child can cause physical, financial, and emotional strain.[114] Several mothers we interviewed told us that their mothers stepped up to care for their grandchildren and were struggling with the financial and emotional stress of child rearing while older.

One mother told us that while she was in jail her 62-year-old mother took care of her two minor grandchildren and great-granddaughter: “[it] aged her, stressed her … [it was] hard on her, hard on her marriage, [she] nearly divorced because of it. … [She] was in fear of being homeless.”[115] Another mother told us that her incarceration put a strain on her 54-year-old mother’s marriage and is hard on her 73-year-old grandmother who now has to “run around with my 4-year-old.”[116]

A 48-year-old grandmother, who is taking care of three of her grandchildren (ages 11, 3, and newborn), said, “It’s a struggle for me. I don’t have [money] taking care of all the kids and I don’t get assistance. … It takes a lot of money to survive out here.”[117]

Karen Turner, a 65-year-old grandmother, has been struggling to take care of her 10-year-old granddaughter, whom she has raised since birth because of her daughter’s frequent incarceration. She lives on a fixed income, relying on social security and veteran’s benefits. Karen told us that her “budget is thin to nothing.” Since raising her granddaughter, Karen’s lifestyle has changed a lot. She has not been able to afford a haircut or manicure in 10 years and sometimes skips eating a full meal, instead subsisting on “toast,” so that she can feed her granddaughter. Although Karen’s daughter is now receiving treatment, as part of a diversion program, Karen estimates it will take “several years” before her daughter gets on her feet. Karen told us she hopes that by then “I’ll be Mimi. … I haven’t really been able to be grandma to her. I’ve been mom, dad, and grandma.”[118]

II. Barriers to Pretrial Release

Despite the presumption of innocence, nearly 11 million people accused of crimes in the US are admitted to local jails each year.[119] Many are incarcerated pretrial for days, weeks, months, or longer because they cannot afford to pay even small amounts of money bail.[120] Women, who generally have fewer financial resources than men, may be even less likely to afford bail or bond.[121]

People locked up in jails face significant pressure to plead guilty to the charges against them in order to get out of jail more quickly and to resume their lives. For mothers, the need to get out of jail to care for their children, especially if they are single mothers, makes the pressure to accept a guilty plea offer especially acute. Several mothers we interviewed in Oklahoma said they were willing to give up their constitutional right to trial in order to get home to their children more quickly.[122]

Money Bail

Pretrial incarceration is supposed to be a means of last resort,[123] but the imprisonment of individuals before they have been charged, convicted, and sentenced is a widespread practice throughout the US and in Oklahoma.

International human rights law and US law both permit pretrial incarceration and the use of pretrial release with conditions, including money bail. However, any pretrial restrictions must be consistent with the right to liberty, the presumption of innocence, and the right to equality under the law.[124] Additionally, pretrial restrictions must not be discriminatory.[125]

On its face, the amount of bail associated with any particular offense may not be discriminatory, but as a practical matter, many people in the US cannot afford even a US$400 emergency expense[126] and women are more likely to have trouble affording bail than men because of higher poverty levels and the gender pay gap, resulting in discriminatory outcomes.

A 2002 survey of jailed people conducted by the US Bureau of Justice Statistics found that jailed men were more likely (60 percent) to be employed during the month before their arrest than jailed women (40 percent).[127] Only a quarter of jailed women reported having an income from wages or salary, compared to two-thirds of jailed men.[128]

A 2016 report by the Prison Policy Initiative found that “[p]eople in jail are even poorer than people in prison and are drastically poorer than their non-incarcerated counterparts.”[129] Prior to detention, jailed women who were unable to post bail earned an average of $11,071, compared to $15,598 for jailed men.[130] Non-incarcerated men earned an average of $39,600 compared to $22,704 for non-incarcerated women.[131] The income disparities are starker for women of color. Incarcerated Black women earned $9,083 prior to arrest and incarcerated Latinas earned $12,178, compared to incarcerated white women who earned $12,954.[132] About half of Black women and Latinas who are single have zero or negative net wealth.[133] And compared to white women, Black women are five times more likely to live in poverty and receive public assistance and are three times more likely to be unemployed.[134] Most of the mothers Human Rights Watch interviewed in Oklahoma experienced substance dependence, homelessness, and/or joblessness.

While nearly all offenses are bail eligible,[135] defendants can be subject to pretrial incarceration not because they are a flight risk or pose a danger to society,[136] but because they cannot afford money bail.

Case law in Oklahoma sets out several key factors courts need to consider when setting bail:

- the seriousness of the crime defendant was charged with;

- defendant's criminal record;

- reputation and mental condition;

- the length of residence in the community;

- family ties and relationships;

- employment history;

- members of the community who could vouch for his reliability; and

- other factors relating to his life, ties to the community or risk of flight.[137]

However, several public defenders told us that, in practice, many judges in Oklahoma set bail according to a district court bail schedule, which provides presumptive amounts of bail based on the charges against the accused in lieu of making an individualized bail determination.[138]

Public defenders also told us that the burden is on them to file a motion to set reasonable bail and to make arguments before a judge consistent with the factors listed above, often weeks after the accused has been in jail.[139] Another public defender told us that counties with larger populations are more likely to use bail schedules to deal with higher case volumes.[140]

Human Rights Watch reviewed bail schedules in Tulsa County and Canadian County.[141]

In Tulsa County, for possession of a controlled drug (felony), the presumptive bail amount is $5,000; for robbery (felony), it is $25,000; and for trafficking marijuana (felony), it is $25,000.[142] If multiple violations are alleged, the presumptive bail amount is the highest listed for any of the violations.[143]

In Canadian County, for any non-violent felony, the presumptive bail amount is $5,000 for Oklahoma residents and $10,000 for non-residents.[144] Violent felonies carry a presumptive $25,000 bail for Oklahoma residents and $50,000 for non-residents.[145] If multiple violations are alleged, the bail amount is combined.[146]

Defendants with higher incomes and more financial resources are likely to secure their release pretrial. Defendants who cannot afford the full amount of bail and cannot obtain a loan by any other means would generally have no choice but to resort to private bail bond companies that will guarantee bail, typically in exchange for payment of a nonrefundable fee—often around 10 percent[147] of the total bail amount (which would be $500 to $5,000 for the examples above).

Obtaining a bail bond may be beyond reach for many or is a strain on families pooling together already limited financial resources. Those who are able to make bond also remain at risk of incarceration if they are unable to afford payments to the bond company.[148]

As one former Oklahoma state court judge told us, “Nobody has that kind of money waiting around. For a lot of folks [bail] might as well be a million. … They will sit in jail until hell freezes over or they plead guilty.”[149]

Whether or not money bail or a nonmonetary form of release is set in a case can also vary depending on the bail practices of the county of arrest.[150]A public defender told us about a client who is a mother of four and has previous credit card fraud convictions. He said that she has pending charges in two neighboring counties (within the same judicial district)—in one county she was released without conditions, in the other county bail was set at $200,000,[151] which demonstrates the “pretty stark difference” in pretrial release outcomes from county to county.[152]

Lengthy Pretrial Incarceration

Even just a few days of pretrial incarceration can have a long lasting impact on jailed parents—they can lose their job, lose their housing, lose their belongings, and lose contact with their children.

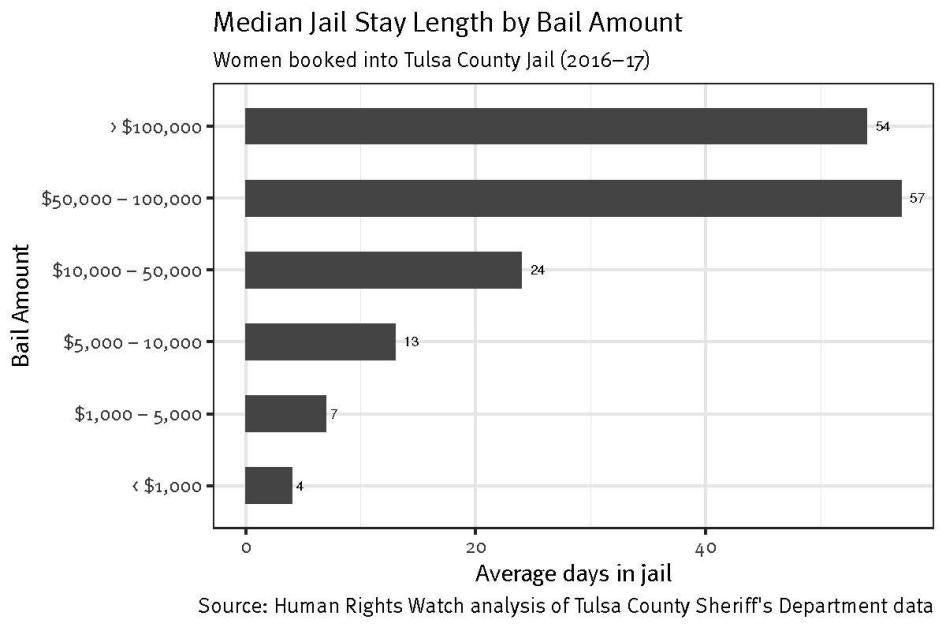

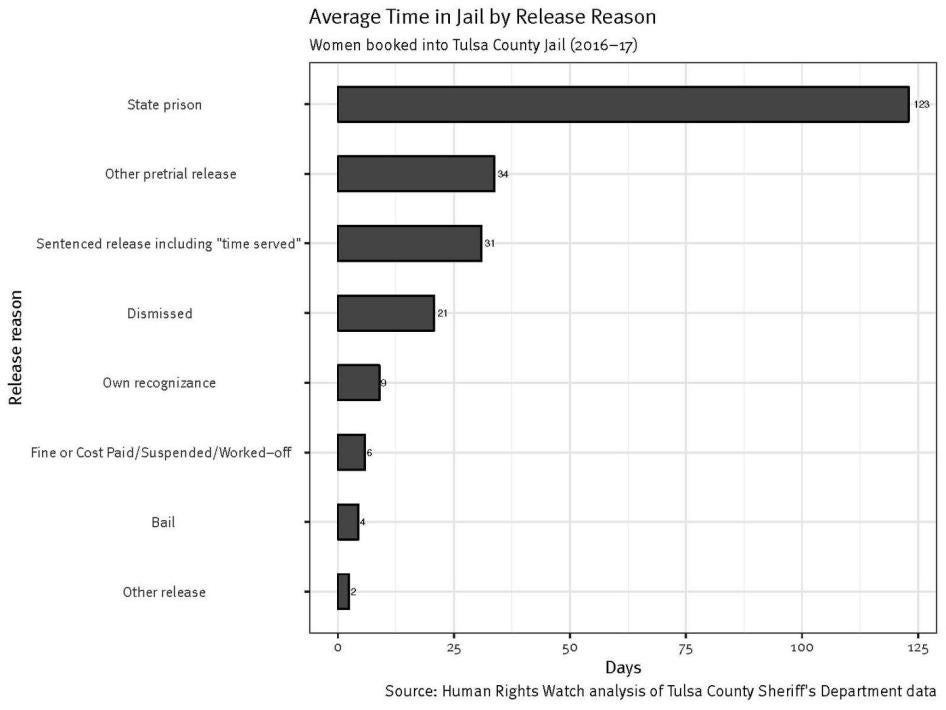

Our analysis of Tulsa County Jail admissions data from 2016 and 2017 found that women, on average, spent 18 days in jail (median = 5) before bailing out.[153] Indigenous women and Latinas stayed in jail longer than Black and white women, on average.[154]

Length of stay is directly connected to the amount of bail set:[155]

The average bail amount for women jailed in Tulsa County was $13,675 (median = $2,092).[156] There was little variation in these averages between women of different races.[157] The higher the bail, the longer women stayed in jail on average.[158]

Over 400 women were booked into jail only to have their cases dismissed.[159] Women who had their cases dismissed were held for 21 days on average (median = 9).[160] About 13 percent of women were released pretrial on their own recognizance after staying an average of 9 days in jail (median = 3) and approximately 5 percent are released pretrial in another manner.[161]

Public defenders in Oklahoma told us that it can take one to three weeks before they are brought in on a case.[162] Some of their clients spend 30 days in jail before they are assigned counsel and brought before a judge to move their case forward, even in cases where the charges against them only carry a maximum sentence of 30 days.[163] One said, “It just doesn’t make any sense how people whose charges carry a 30-day sentence … have to wait the same amount of time to go to court as people whose charges carry longer sentences.”[164]

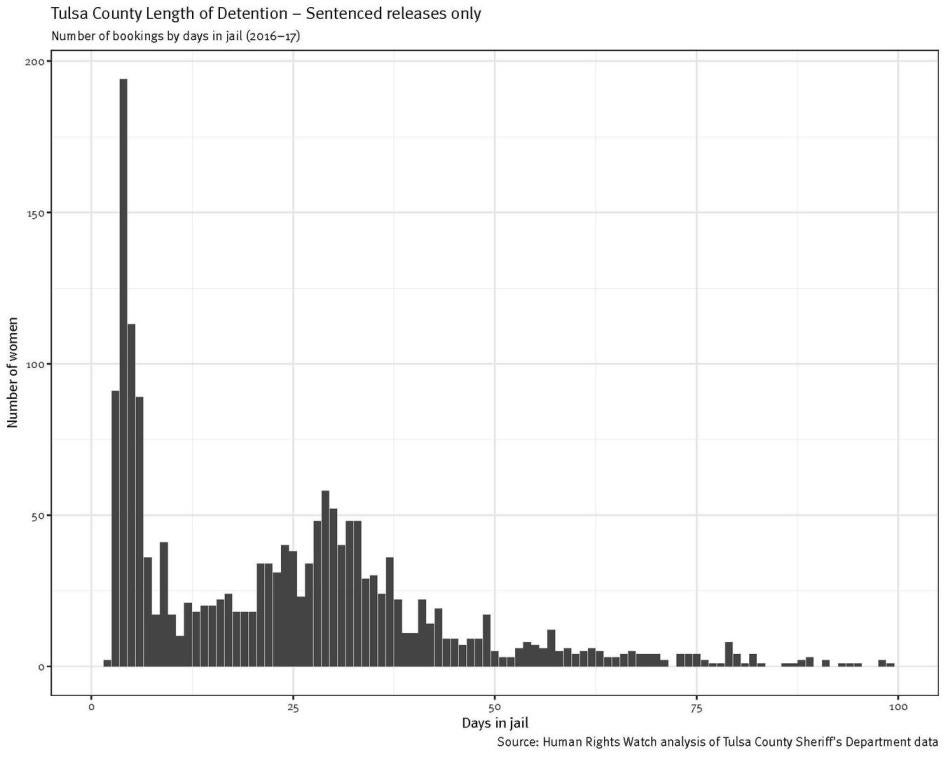

Our data analysis shows that 17 percent of women stayed in jail until they were sentenced, including “time served” sentences.[165] About one in three of this 17 percent pleaded guilty within the first 10 days of their jail stay, with the highest numbers coming on days four and five.[166] Another large proportion of women are released around the 30 day mark, reflecting what public defenders told us about the timeframe between arrest and when a meaningful hearing is held.[167]

While most women left Tulsa County Jail within 30 days, 781 women were incarcerated between 30 and 60 days, 200 between 60 and 90 days, 185 between 90 and 180 days, 61 between 180 and 365 days, and 10 for more than 365 days.[168]

Many of the mothers we interviewed were in jail for several months and some told us that their scheduled dates to appear in court were repeatedly postponed, or in other words, they were “passed” over:

- Candace Smith, a 26-year-old mother of five incarcerated at Tulsa County Jail, recalled a conversation with her mother: “[I told her] ‘Mom, I think I’m lost in the system for real.’ I have been passed seven times in a row and nine times total since I have been here. … I haven’t seen an attorney, haven’t seen a courtroom or a judge [in four months].”[169]

- Alyssa Barnes, a 38-year-old mother of three incarcerated at Tulsa County Jail, told us that she had been “passed” six times in three months. She told us she did not have a public defender until recently and the private attorney she had hired to represent her had failed to show up to court on several occasions.[170]

- Mary White, a 34-year-old mother of one, was incarcerated at Oklahoma County Jail in 2014. She told us that she had no court date for three months and was told that her paperwork “fell through the cracks.” She was in jail for 10 months before she eventually was accepted into a diversion program.[171]

- Sonya Pyles, a 42-year-old mother of three and custodial grandmother, told us that her court dates were 30, 60, and sometimes 90 days apart when she was incarcerated at Tulsa County Jail in 2014.[172]

A Tulsa County public defender told us that when a defendant is “passed,” they “[do] not know what’s happening with their case. … There’s a lot of sitting in the dark.”[173]

Unique Pressure on Mothers to Plead Guilty

Nationwide, nearly all cases in state and federal courts are either dismissed or resolved via guilty pleas.[174] Negotiated plea agreements can be beneficial to the accused, however, prosecutors have most of the power in shaping a case’s outcome, pretrial incarceration itself negatively impacts case outcomes,[175] and it can take months and even longer than a year to have a trial.[176]

The lengthy wait to go to trial coupled with the jail environment can coerce a defendant to accept a guilty plea that, in the long run, may not be in their best interest.[177] Several mothers told us that the conditions in jails were unbearable—from sleeping on concrete without mattresses and blankets[178] to the lack of feminine hygiene products.[179] Mothers also told us that three or four women were placed in a two-person cell in Oklahoma County Jail, though there is some evidence that this may no longer be the case.[180] One mother said that her anxiety attacks were worsened while in jail because of the conditions.[181]

In addition to the already overwhelming pressure to plead guilty, some mothers told us that they accepted a guilty plea offer to a noncustodial sentence because they needed to return home quickly to care for their children:

- April Weiss, a 30-year-old mother of three, was charged with robbery and detained in Oklahoma County Jail in 2012. She said that she pleaded guilty and received a 10-year suspended sentence, against the advice of counsel. April said she could have fought the charge but she decided she had to get back to her children: “I wasn’t thinking ‘Oh I am going to be a felon [for] the rest of my life,’ I was just thinking I have to take care of my kids.”[182]

- Tanisha James, a 25-year-old mother of four, believed that the domestic violence charges against her were likely to be dismissed but after being detained in Oklahoma County Jail for nearly a month, she pleaded guilty in exchange for five years probation. She told us “I was away from my kids and all I wanted to do was be around them.”[183]

When Vanessa Evans, a 21-year-old mother of one, was arrested, her two-month-old daughter was in the car. She said that the bail amount was too high for her to pay. After four months at Tulsa County Jail, Vanessa said she chose to participate in a diversion program instead of fighting her charges because “I didn’t want to miss out on my baby anymore.”[184]

Mothers who spent time incarcerated pretrial in Oklahoma jails also told us that they were concerned about losing custody of, or contact with, their children.

Chloe Washington, a 47-year-old mother of six, was arrested for possession of a firearm and attempted armed robbery. Bail was set at $48,000, which she could not afford to pay. She told us that she was incarcerated at Oklahoma County Jail for nine months, and only saw her children twice via video, before she accepted a guilty plea. She said, “I’m thinking I got to get out of here, I got to get these kids or they’ll be adopted out.” As part of her sentence, Chloe was required to complete a rehabilitative program in prison in addition to receiving an eight-year suspended sentence.[185]

III. Barriers to Parent-Child Contact

Incarceration should not deprive parents of their right to remain in contact with their children. Family visitation and communication in jails and prisons has been shown to produce multiple benefits: stronger bonds between incarcerated people and their families, improved post-release outcomes such as lower recidivism rates, greater parent-child attachment, and decreased misconduct while behind bars.[186] Research conducted in Minnesota found that a single visit between a parent and child could reduce recidivism rates.[187]

Regular contact between parents and children is necessary to ensure stability for both parent and child.[188] And if a jailed mother has children in foster care, having a substantial relationship with her children is essential for reunification after release. As one non-profit lawyer explained, “you can’t have a substantial relationship with kids if there is no visitation.”[189]

Despite all the benefits of facilitating family relationships during incarceration, the visitation and communication policies and practices in Oklahoma’s jails create almost insurmountable roadblocks to meaningful parent-child interactions.

Visitation and communication may be severely limited in jails because jails are meant to house people for shorter periods of time—but the reality is that many people spend substantial periods of time incarcerated in jails. Some jailed mothers we spoke with did not see their children at all or only spoke with them once or twice over the telephone during long periods of pretrial incarceration.[190] Even if jailed mothers manage to have regular contact with their children, it is not a replacement for being physically present. One jailed mother of five, who had been incarcerated for 16 months awaiting trial, said of her absence: “you miss so much when you’re gone, … from first teeth to first words.”[191]

Policies and Practices that Limit or Bar Family Contact

Oklahoma is comprised of 77 counties and each county has their own jail.[192] Because many Oklahoma county jails provide no information on visitation and communication policies online, Human Rights Watch undertook a 25-county survey by calling county jails and sheriffs’ offices. The information we gathered is set forth below, and in the appendices of this report, and confirms what several public defenders we interviewed told us: jails “treat visitation as a perk”[193] and the “rules [are] in [a] constant state of flux.”[194] Indeed, during the course of our survey, a few jails discontinued in-person visitation, opting for video visitation as a substitute.[195] As Mark Opgrande, the public information officer for the Oklahoma County Sheriff’s Office told us: “jail isn’t conducive to bring people in for visits. [It’s a] packed house, it takes up time and energy, and the jail is understaffed.”[196]

In-Person Visitation

Only six out of 25 county jails surveyed told us that regularly scheduled in-person visitation is available.[197] The form and quantity of visitation varies. In Comanche County, Stephens County, and Wagoner County, in-person visitation is the only form of visitation available.[198] Visits are offered one to two times per week and the length of visits range between 15 and 30 minutes.[199] Stephens County Jail[200] does not permit children to visit and Tulsa County Jail does not permit children under 14 to visit, unless special procedures are followed or the jailed mother is participating in the Parenting in Jail program.[201] Le Flore County Jail allows a maximum of three child visitors each visit.[202] Jailed people must wait between one to 10 business days before they can begin to receive visits, depending on the jail’s policy.[203] Comanche County Jail only permits jailed people to visit with their biological children.[204]

All in-person visits are held behind a glass barrier, with the exception of visits between mothers and their children as part of the Parenting in Jail Program at Tulsa County Jail.[205]

Contact visits are especially important for incarcerated mothers with young children because young children need physical contact for bonding and attachment[206] and young children cannot understand why their mother cannot hold, touch, or play with them.

The only mother-child visitation program[207] in Oklahoma jails is located at Tulsa County Jail, which permits full contact visits between eligible jailed mothers and their children once per week.

|

Parenting in Jail Program[208] The Parenting in Jail program at the Tulsa County Jail was established with a private grant in September 2014. The program works with approximately 20 women at a time and has 15 new clients every seven weeks. More than 250 women have participated since its inception. Since 2015, the program has provided women with mental health and substance use assessments, treatment plans, and advocacy, in addition to the Parenting Inside Out curriculum. The program works collaboratively with incarcerated mothers to meet their goals, which include drug and alcohol recovery, relationship-building with children and families, and coping with trauma. Most treatment plans include individual counseling. The program also provides support to caregivers, coordinates with child welfare services to secure visitation, and works with reentry specialists that support mothers while incarcerated and when they return to their communities. The Parenting Inside Out curriculum is a six-week course (two hours per day, five days per week) run in the county jail. Mothers who complete six classes can begin to have visits with their children. Visits take place every Thursday for one hour. Mothers spend time with their children in a designated visiting area where mothers are allowed to change out of the jail-issued orange shirt. The visiting room is in a library-like setting with colorful placemats and toys. About 34 percent of program participants have weekly visits. Mothers housed in restrictive housing (segregation) or who are classified at higher security levels are not eligible to participate and priority is given to mothers with children ages eight or younger. Mothers are required to have a child under 14 to participate. Fifty percent complete the parenting course and the program has a 20-25 percent graduation rate. Because the program is housed inside a jail, most women are released prior to completion. The majority of program participants have been women of color, with 45 percent identifying as white, 27 percent African American, 15.9 percent Native American, 10.6 percent Latina, and 1.6 percent Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. |

Human Rights Watch observed a scheduled visitation day at Tulsa County Jail during which four mothers were reunited with their children for one hour. For example, Candace Smith, a 26-year-old mother of five, gave birth to her youngest child while detained for more than eight months at Tulsa County jail.[209] As part of the program, she was able to visit with three of her children, including her seven-week-old newborn. During the visit we observed, Candace held her infant while simultaneously playing and talking with her 11 and 3-year-old daughters. Lori Smith, Candace’s mother, told us that the parenting program has given Candace the opportunity to bond and develop a close relationship with her newborn, despite their separation.[210]

Vanessa Evans, a 21-year-old mother of one, told us that she was concerned that being in jail would impact her relationship with her 1-year-old daughter. “I just didn’t think my baby would know me, … we wouldn’t have a connection. … [Because of the Parenting in Jail program] I got to bond with my baby. … I believe that has created the bond my daughter and me have now. … It was the first time I got to hold her since I was arrested.”[211]

However, a few mothers we spoke with told us they were in jail for two to seven months before they could get into the program and begin visits.[212]

Jailed mothers may also face difficulty receiving visits if their children are in the custody of Oklahoma’s child welfare system (OKDHS). Some children may have been placed in OKDHS custody prior to their mother’s arrest, while others may have been placed in OKDHS custody as a result of their mother’s arrest. While parents have a right to regular visitation and communication with their children,[213] OKDHS policies provide a great deal of latitude to OKDHS caseworkers to decide whether and how to provide for child visitation depending on the OKDHS “case plan goal” for the child.[214] Jailed mothers are thus reliant on the juvenile court system, OKDHS, and jail staff to facilitate visitation between them and their children.

Even in cases in which OKDHS caseworkers may decide to arrange for visitation, OKDHS policy offers contradictory standards for the frequency of contact between caseworkers and parents. One policy requires face-to-face contact between jailed parents and caseworkers 14 days after a child is removed from the home and every 30 days thereafter;[215] another policy provides 30 days to make contact with parents and requires that communication be arranged via jail (correctional) case managers.[216]

Staff at the Parenting in Jail program told us that arranging visitation between mothers and their children is easier when OKDHS is not involved.[217] Nancy, a clinician, said that some OKDHS workers are supportive and help facilitate visits but others see their job as “needing to protect the children by keeping them away from their mother.”[218] Noting that OKDHS caseworkers sometimes argue that visits are inappropriate because the child is experiencing trauma, Nancy emphasized: “Don’t you think being separated from [their] parents is part of that? Including biological parents and caregivers can be healing. … [Visits] might be upsetting [for children] but that doesn’t mean [they are upset] from seeing their parents.”[219]

Judges in juvenile court (overseeing OKDHS cases) can order visitation but several attorneys and service providers told us that key decision makers in OKDHS cases believe that jail is an inappropriate and traumatizing environment for children thus leading to no visitation.

An assistant district attorney in Oklahoma County who handles juvenile court cases said:

For incarcerated parents, pretty much no judges order visitation. … A lot of judges worry about the potential trauma of the child going in and out of those facilities. … Even more so for jails than it is for prisons because of the environment of the jail. … It’s traumatizing in the judge’s eyes.[220]

An attorney representing children in juvenile court also told us that visitation in jail “just doesn’t seem to happen … and I just don’t see how it would happen” given the conditions of jails.[221]

If parent-child visits in jail are ordered and facilitated, OKDHS policies allowing 30 days between communications, and requiring arrangements be made with jail case managers, can slow things down.[222] Interviewees explained that it could take months before visitation starts. Travis Smith, a public defender in Tulsa County, said, “[Clients] don’t have meaningful communication with their children. … We don’t see [OK]DHS bringing children to visit in the jails until around three months [have passed]. … They try really hard to avoid [setting up visits].”[223]

While some judges may arrange for visitation corresponding with court proceedings,[224] there appears to be limited access to visitation within the jail and very few opportunities for regular visitation outside of the jail setting.

Without court orders, OKDHS facilitation, and cooperation from jails, many jailed mothers are separated from their children and unable to see them face-to-face for the duration of their pretrial incarceration. This outcome has negative repercussions beyond the immediate harms because parents are expected to see and communicate with their children regularly to successfully reunify with them post-release.

Four of the six jails permitting in-person visitation told us that people in segregation for disciplinary reasons are not able to receive visits.[225] This can affect parent-child visitation:

- Tiana Henderson, a 21-year-old mother of one, said that she was placed in segregated housing at Tulsa County Jail following an allegation of misconduct. Tiana told us “[the investigation is] preventing me from seeing my baby.”[226]