A Price Too High

Detention and Deportation of Immigrants in the US for Minor Drug Offenses

Summary

Finally Off Drugs But Facing Deportation and Family Separation

Marsha Austin (second from right) with her US citizen husband and three of her daughters, all US citizens or lawful permanent residents. Austin, a lawful permanent resident from Jamaica, is currently fighting deportation as an “aggravated felon” because a 1995 conviction for attempted sale of a controlled substance stemming from a long struggle with dependency on crack cocaine. © 2014 Private Marsha Austin is facing deportation for a 1995 conviction for attempted criminal sale of a controlled substance in the third degree, stemming from her long struggle with a dependency on crack cocaine. A 67-year-old great-grandmother, Austin came from Jamaica to New York as a lawful permanent resident in 1985. Other than two sons in Jamaica, her entire family—husband, seven children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren—lives in the United States. They are all US citizens or permanent residents. “I live in a drug-infested area,” Austin said, describing her neighborhood in the Bronx in New York City. According to Austin, she began using drugs when her mother was killed after being hit by a train. For eight days, her family did not know what had happened to her. Austin said she was devastated by her death and accepted a cigarette laced with crack cocaine at her funeral. Austin said she managed to hide her dependency from her family for many years, but her drug dependency led to a lengthy record of minor convictions, mostly for simple possession. The 1995 conviction for attempted sale happened, Austin said, when an undercover police officer asked her to go to a roof and buy five units of crack cocaine for him, for which he gave her five dollars. She pled guilty to attempted sale. She said her criminal defense attorney failed to tell her the conviction could lead to deportation. Austin’s convictions led to little or no jail time, but in 2010, Austin said her husband had a seizure, and she drank alcohol, a violation of probation, to calm herself. Her probation violation led to a 90-day sentence, at the end of which, immigration authorities arrested her. Austin eventually spent two-and-a-half years in immigration detention at a jail in Hudson County, New Jersey. ICE repeatedly opposed her release, asserting she was under mandatory detention for her drug crimes, but then unexpectedly released her in March 2013. Two days after her release, Austin was back in her treatment program. Austin proudly reports that she has been “clean as a whistle” for the past five years. The US government continues to argue, however, that she is subject to deportation for the “aggravated felony” of her 1995 attempted sale conviction. Austin is desperate to remain in the US. Her husband is in very bad health, as is her daughter who suffered a breakdown after her own daughter’s serious illness. Austin said, “My kids and grandkids, that’s what I’m living for now.”[1] |

Detained and Denied the Chance to Say Goodbye to His Dying Father

Arnold Aguayo, holding a photo of his father, Arnoldo Aguayo, for whom he is named. Aguayo, a lawful permanent resident who grew up in the US, was held in mandatory immigration detention for seven months in 2011 and 2012 while he fought deportation for drug convictions. During that time, his father, a US citizen, had two heart attacks and died. Aguayo requested but was denied a short leave from detention to say goodbye. © 2015 Timothy Wheeler for Human Rights Watch According to Arnold Aguayo, his parents brought him to the US from Mexico when he was less than a year old. He grew up in Compton, California, with parents and siblings who are all US citizens and permanent residents. Aguayo, now 38, is himself a permanent resident with five US-born children. Aguayo said he was particularly close to his father growing up. “I was a daddy’s boy, I would follow him around.” Aguayo is a plumber, and he credits his father for having taught him how to fix anything, as well as “how to be humble with people, to basically be a good person.” His father suffered from gout and diabetes, and Aguayo reported he had been his caregiver: “I used to do everything for him…. I was always there making sure he took his medicine.” Aguayo struggled with dependency on methamphetamine for many years. He tried to keep it “stable” and not to let it affect his family, but he ended up getting arrested several times. One time, the police pulled him over, he said, claiming his music was too loud, but he believed, “Out here, you look young, they’re just going to pull you over for the hell of it.” He ultimately got arrested in September 2011 for violating probation because he had not gone to treatment. Aguayo said he had already sobered up by then, motivated by his wife and children, but going to treatment required him to miss work. After he had served four months in LA County Jail for violating probation, immigration authorities picked him up and told him the US government wanted to deport him. Aguayo, as a permanent resident with possession convictions, was eligible to apply for a type of pardon, lawful permanent cancellation of removal, and fight deportation. But under US law, any drug conviction triggers mandatory immigration detention while proceedings are pending. If Aguayo had been arrested for a criminal offense, he would have had a right to a bail hearing. He had no such right to apply for an immigration bond. Aguayo was ultimately in immigration detention for seven months. During that time, his father had two heart attacks and eventually died. His attorney and his family tried desperately to get him released so he could see his father one last time, but he said immigration authorities responded, “It’s not that important.” Aguayo even considered accepting deportation just so he could be released and see his father, but his family talked him out of it. “I still haven’t gotten over it,” he said. Aguayo had been the primary breadwinner, and without him, his partner and children could no longer pay the rent on their home. His oldest son was diagnosed with depression. He says his detention put such a strain on his relationship that they broke up, and his partner, who is Mexican, went back to Mexico and took their two children with her. Aguayo said he now only sees them on holidays and during school vacations. If he had never been detained, Aguayo believes, “I would still have a stable home, I’d still have my kids living with me.…Whatever I had planned [for the future] was shattered.” He wanted to share his case with Human Rights Watch because, “I don’t want this to happen to anyone else.”[2] |

There is growing consensus in the United States today that existing criminal drug laws and policies—defined by criminalization of drug use and possession, and disproportionately severe sentences for drug offenses overall—are not working and, in many respects, are doing more harm than good.

Legislators from both major political parties have called for reforms of harsh federal mandatory minimum sentencing laws. The US Department of Justice has announced new reforms and initiatives intended to address the fact that half of the more than 200,000 people in federal prisons are incarcerated for drug offenses. Dozens of states have enacted far-reaching reforms, from providing judges with more discretion in sentencing drug offenders to decriminalizing and even legalizing possession of marijuana. Many jurisdictions have created drug courts and other diversion programs to minimize the use of incarceration and criminal sanctions, reflecting the principle that the harms of drug dependency are often better treated as a public health issue, rather than a criminal justice matter.

Reformers are often motivated by concerns that harsh drug laws and enforcement policies are unjust, racially discriminatory, ineffective, and wasteful, and that mandatory minimum laws in particular unfairly apply a one-size-fits-all policy to people who deserve more individualized consideration. Although existing and proposed reforms could and should go further, the momentum toward reform is a welcome effort to remedy the many ways in which drug law enforcement has contributed to serious human rights violations in the US.

This careful reexamination of US drug policy, however, has stopped short of investigating and reforming US immigration laws that essentially mandate detention, deportation, and exile each year for tens of thousands of immigrants, including lawful permanent residents, convicted of drug offenses—sometimes for offenses so minor as to result in no criminal justice sentence of imprisonment.

Deportations for Drug Offenses

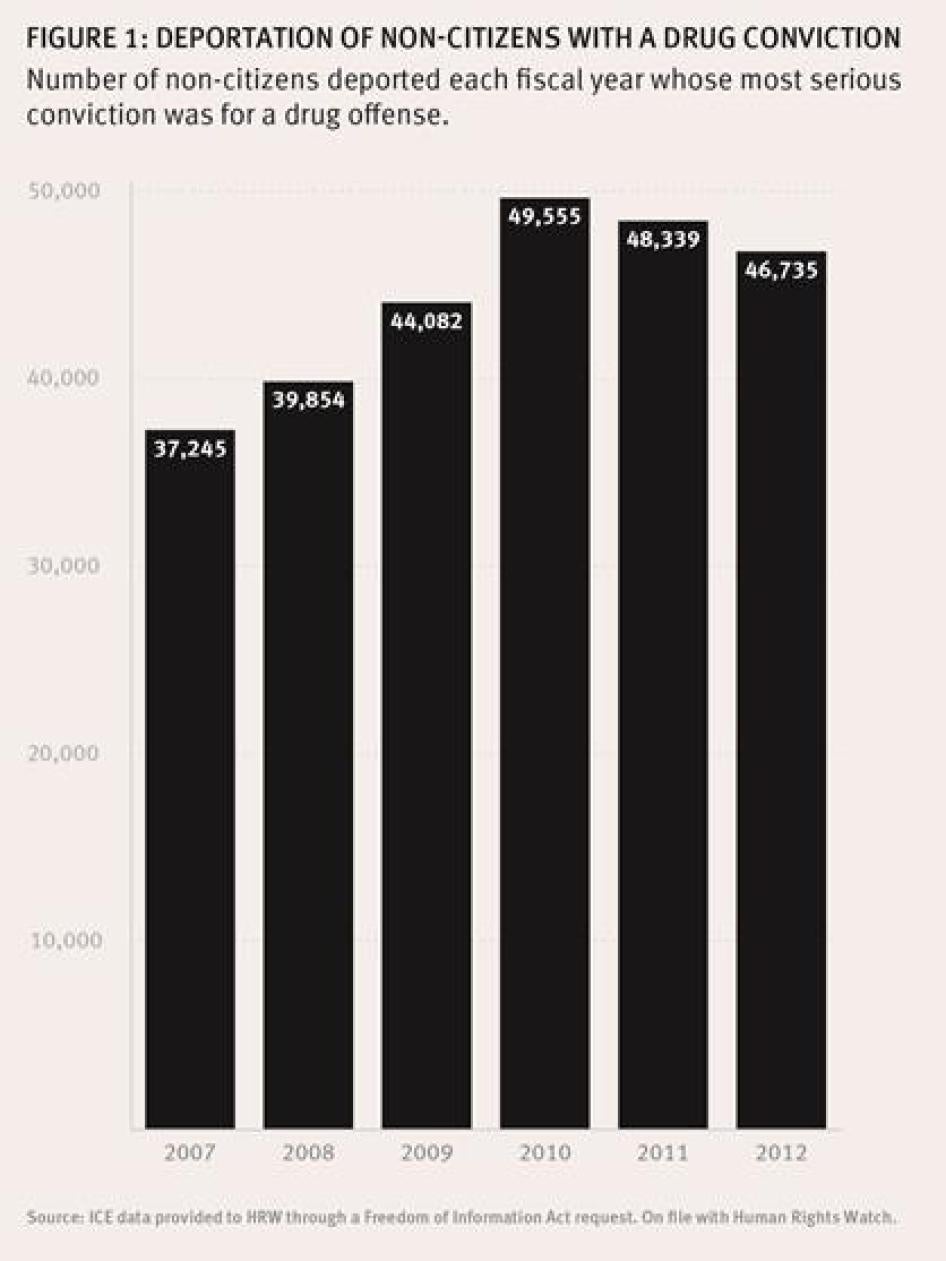

According to data released by the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in response to a Human Rights Watch Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, deportations of non-citizens whose most serious conviction was for a drug offense increased 22 percent from 2007 to 2012, totaling more than 260,000 deportations over the same period. Deportations of non-citizens with convictions for drug possession increased 43 percent. ICE claims that it does not keep track of whether these individuals were lawful permanent residents or undocumented immigrants. But, as detailed in this report, the US is deporting a significant number of both permanent residents and undocumented individuals with strong family and community ties to the US, often for minor or old drug offenses.

US immigration law began to dictate severe immigration consequences for non-citizens with drug offenses in the 1980s and 1990s, often as part of legislation passed in support of the US “War on Drugs.”

Lawful permanent residents— that is, people with legal immigrant status in the US— can be deported for any drug offense, with the sole exception of a conviction for possession of 30 grams or less of marijuana. Many lawful permanent residents with convictions for simple possession are eligible to apply for and receive “cancellation of removal” to remain in the US, but they must often fight their cases while being detained without bond. If the offense is considered “drug trafficking,” even if it is a low-level sales offense involving small amounts of drugs—such as selling ten dollars-worth of cocaine—permanent residents face deportation as “aggravated felons,” and are disqualified from almost every defense to deportation. In such cases, immigration judges, like judges forced to impose mandatory minimum sentences in criminal cases, are barred from considering each case individually and taking into account such factors as the circumstances of the offense, rehabilitation, length of residence in the US, and ties to US family.

Unauthorized immigrants with any drug conviction, even a minor possession offense, face a lifetime bar from ever gaining legal status even if they have close US citizen relatives. US law imposes a bar to gaining legal status for other crimes as well, but while non-citizens with convictions for many other crimes, like assault or fraud, can apply for a “waiver” of the bar if they can show a US citizen or permanent resident family member would suffer extreme hardship, no such waiver exists for drug offenses (the sole exception is a single conviction for possession of 30 grams or less of marijuana).

Once deported, non-citizens are permanently barred by their drug offenses from returning to live with their families in the US. For many, as described by one immigration attorney, deportation can feel like a life sentence without the possibility of parole.

Non-citizens who fear persecution if returned to their countries are ineligible for asylum if they have a drug conviction that has any element of sale, because such offenses are all considered drug trafficking convictions and deemed “particularly serious crimes.”

US immigration law also mandates detention, with no opportunity to apply for bond, for anyone (including lawful permanent residents) with a conviction for a controlled substance offense. Thus, immigrants who received no sentence, or relatively short criminal sentences, for minor drug offenses can end up spending months or even years in immigration detention.

Immigrants who successfully complete drug diversion programs and have their convictions expunged can still end up deported and permanently separated from their families for these offenses. Even pardons do not eliminate the immigration consequences of a drug crime.

Criminal defense attorneys have an obligation, under the 2010 Supreme Court case Padilla v. Kentucky (involving a permanent resident who pled guilty to transporting marijuana) to advise their non-citizen clients about the immigration consequences of a guilty plea, and defense attorneys who are well-versed in immigration law are sometimes able to negotiate plea deals that allow their clients to avoid deportation. But numerous immigrants and immigration attorneys reported cases in which the criminal defense attorneys had failed to properly advise their clients. Indigent immigrants must rely on court-appointed counsel, whose access to immigration law expertise and other resources can vary widely from state to state and county to county. Furthermore, because minor drug offenses increasingly carry little jail time, criminal defense counsel may be particularly unaware that severe immigration consequences can follow a conviction or plea. In some jurisdictions, the drug offenses that trigger detention and deportation are so minor that individuals regularly plead guilty to these crimes without a lawyer.

The ability of defense counsel to negotiate “immigration-safe” pleas can also vary widely depending on the willingness of prosecutors in that jurisdiction to consider immigration collateral consequences. While some prosecutors have publicly spoken out against unfair immigration collateral consequences, others remain reluctant and sometimes actively hostile toward efforts by defense counsel to avoid such consequences. Immigrants who plead guilty without proper advice from their attorneys can sometimes vacate their pleas and avoid deportation, but the feasibility of post-conviction relief also varies significantly from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

Among the cases reported to Human Rights Watch are the following:

- Raul Valdez, a permanent resident from Mexico who had grown up in the US from the age of one, was deported in 2014 because of a 2003 conviction for possession of cannabis with intent to deliver, for which he had been sentenced to 60 days in jail.

- Ricardo Fuenzalida, a permanent resident from Chile, spent three months in mandatory immigration detention in 2013 fighting deportation because of two marijuana possession convictions that occurred 13 years earlier.

- Abdulhakim Haji-Eda, a refugee from Ethiopia who came to the US at the age of 13, was ordered removed as a drug trafficker for a single conviction for selling a small quantity of cocaine at the age of 18. Now 26 years old, he has no other convictions and is married to a US citizen and has two US citizen children.

- Marion Scholz, a permanent resident from Germany who had lived in the US for over 45 years, was deported in 2014 because of two convictions for misdemeanor possession stemming from drug dependency, which she has since overcome.

- “Antonio S.,” who came to the US from Mexico when he was 12 and was eligible for a reprieve from deportation as a “DREAMer” under the executive program Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, was detained for over a year and deported after a conviction for possession of marijuana, a municipal violation to which he pleaded guilty without an attorney.

- “Alice M.,” a 41-year-old graphic designer and Canadian citizen, reported she is barred from living in the US with her US citizen fiancé because of a single 1992 conviction for cocaine possession she received in Canada in her last year of high school, a conviction that was pardoned long ago in Canada.

- “Mr. V.,” a refugee and permanent resident from Vietnam, was ordered deported in 2008 for a 1999 conviction for possession of crack cocaine. Although he has since been granted a full and unconditional pardon from the state of South Carolina, Mr. V. remains under a deportation order and remains in the US only because of restrictions on the repatriation of certain Vietnamese nationals.

Drug offenses are not the only types of crime that trigger such draconian immigration consequences. Human Rights Watch has long advocated for changes to the US immigration system that essentially mandate deportation, exile, and family separation for a wide range of offenses. But this report focuses on the impact drug convictions have had on immigrants because the categorical treatment of nearly all drug offenses as warranting detention and deportation, on top of any criminal justice sentence, is in such sharp contrast to the growing recognition that severely punitive sentences for drug offenses in the criminal justice system are unwarranted and ineffective.

Deportations under the Obama Administration

The impact of abusive immigration laws has been exacerbated by the Obama administration’s pursuit of a deportation policy focused on immigrants with criminal convictions.

Despite the administration’s claims that enforcement targets those who pose a threat to public safety, many of the cases reported to Human Rights Watch involve immigration arrests of people with convictions for drug offenses, many of them minor or committed many years earlier. Those arrested were often lawful permanent residents or unauthorized immigrants with US citizen family.

In announcing his executive action in November 2014, President Obama said “[O]ver the past six years, deportations of criminals are up 80 percent. And that's why we're going to keep focusing enforcement resources on actual threats to our security. Felons, not families. Criminals, not children. Gang members, not a mom who's working hard to provide for her kids.” But the reforms, while a positive step in some respects, largely fail to address the dynamic of targeting immigrants who pose little to no threat to public safety.

At the same time, the executive actions hold out the possibility of a more nuanced approach. The eligibility requirements for its executive programs (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, which began in June 2012, and the newer programs announced in 2014) do not automatically disqualify anyone with a misdemeanor conviction for simple possession, though they do disqualify anyone with a felony conviction. The most recent enforcement priorities memorandum issued by the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS), effective January 5, 2015, also states the administration would be willing to consider exercising prosecutorial discretion in favor of individuals with criminal convictions, including those that make them enforcement priorities, if they can show strong equities, such as length of time since the conviction, length of time in the US, and family or community ties to the US.

As of date of publication, DHS has not issued any data or other information regarding the implementation of the memorandum and the implementation of the newer executive actions has been delayed by an injunction granted in response to a federal lawsuit.

Drug Reform Should Include Immigration Reform

The Obama administration recognizes that the US criminal justice system can produce deeply unjust outcomes and can have a particularly devastating impact on communities of color. Attorney General Eric Holder, referring to “the destabilizing effect [of the federal criminal justice system] on particular communities, largely poor and of color,” specifically noted in a 2013 speech to the American Bar Association that “tens of thousands of statutes and regulations … impose unwise and counterproductive collateral consequences,” and further stated his department’s intent “to consider whether any proposed regulation or guidance may impose unnecessary collateral consequences on those seeking to rejoin their communities.”[3] Yet by doggedly pursuing the deportation of non-citizens with criminal convictions, without more nuanced acknowledgment that not all “criminal aliens” actually pose a threat to public safety or national security, the US government has exacerbated the consequences of harsh drug enforcement and barred hundreds of thousands of people with convictions for nonviolent drug offenses from rejoining their communities.

At the same time, the US Congress has shown no inclination to reform draconian laws that have denied lawful permanent residents and long-term unauthorized immigrants with criminal convictions the opportunity to have an individualized hearing before an immigration judge, the kind of discretion liberals and conservatives increasingly recognize is needed in the criminal justice system. Congress has sought instead to include more offenses in the category of “aggravated felonies” that require deportation of non-citizens with criminal convictions, regardless of how minor or old the offense and without any opportunity for the affected individual to get an individualized hearing before a judge Hundreds of thousands of families have been separated due to such laws.

Under international human rights law, the US government has the right to regulate its borders, and states have a particular interest in restricting the entry of those who pose a threat to public safety. But current US immigration policies toward drug offenders violate several provisions and principles of international law, including that punishment be proportional to the offense, the right to present defenses to deportation, the right to family unity, and the best interests of the child.

The president, Congress, and all who care about reforming US drug policy and reducing excessive punishment for drug offenses should extend their reform efforts to include US immigration law and policy. The US should restore immigration judges’ discretion to consider cases involving drug offenses and other criminal convictions on a case-by-case basis, weighing such factors as the seriousness of the offense, evidence of rehabilitation, family ties, the best interests of any minor children, and other similar factors.

Congress should eliminate the permanent bar to entering the US for any drug offense, and at the very least, should create a waiver that provides those with strong family ties the opportunity to demonstrate they are not a threat to public safety. Congress should also eliminate mandatory detention and amend the overly broad definition of a conviction that can include expunged and pardoned drug offenses.

State and local governments and law enforcement agencies should help minimize the collateral consequences of nonviolent drug offenses by creating diversion programs that help non-citizens avoid a conviction, as defined by immigration law, and decriminalizing the personal use of drugs.

It is encouraging that many US legislators and policymakers are working to create a criminal justice system that treats drug offenders more fairly and humanely. We urge these legislators and policymakers not to ignore US families and communities being destroyed by detention, deportation, and family separation that can follow convictions for the same offenses.

Key Recommendations

To the United States Congress

- Eliminate deportation based on convictions for simple possession of drugs.

- Ensure that all non-citizens in deportation proceedings, including those with convictions for drug offenses, have access to an individualized hearing where the immigration judge can weigh evidence of rehabilitation, family ties, and other equities against a criminal conviction.

- Ensure that refugees and asylum seekers with convictions for sale, distribution, or production of drugs are only considered to have been convicted of a “particularly serious crime” through case-by-case determination that takes into account the seriousness of the crime and whether the non-citizen is a threat to public safety.

- Ensure that non-citizens who are barred from entering the US and/or gaining lawful resident status because of a criminal conviction, including for drug offenses, are eligible to apply for individualized consideration, i.e., a waiver of the bar, based on such factors as the above mentioned.

- Eliminate mandatory detention and ensure all non-citizens are given an opportunity for an individualized bond hearing.

- Redefine “conviction” in immigration law to exclude convictions that have been expunged, pardoned, vacated, or are otherwise not recognized by the jurisdiction in which the conviction occurred.

- Decriminalize the personal use of drugs, as well as possession of drugs for personal use.

To the Department of Homeland Security

- Provide clear guidance to immigration officials that a positive exercise of prosecutorial discretion may be appropriate even in cases involving non-citizens with criminal convictions, with particular consideration for lawful permanent residents and non-citizens whose most serious convictions are for nonviolent offenses, including drug convictions, that occurred five or more years ago.

- Provide all non-citizens who have been in detention for six months or more with a bond hearing.

To State and Local Governments

- Ensure drug courts and diversion programs do not require a guilty plea from defendants that would constitute a conviction that triggers deportation, mandatory detention, and other immigration consequences even upon successful completion of the program.

- Remove barriers to post-conviction relief for non-citizens convicted of nonviolent drug offenses through legal error, including through guilty pleas obtained without adequate advice from defense counsel on the potential immigration consequences of the plea.

- Decriminalize the personal use of drugs, as well as possession of drugs for personal use.

Methodology

This report is based primarily on interviews conducted between February 2014 and June 2015 and information obtained from a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. It also relies on federal court decisions, news articles, and other publicly available sources.

Human Rights Watch conducted more than 132 interviews with non-citizens who had been arrested for or convicted of drug offenses, the vast majority of whom were placed into deportation proceedings; family members; immigration and criminal defense attorneys and paralegals; prosecutors; law enforcement officials; and drug policy and criminal justice reform advocates. We interviewed individuals, family members, and attorneys regarding a total of 71 cases and reviewed news articles and federal court decisions in several additional cases.

Criminal defense and immigration attorneys and local advocates referred us to individuals and families in many cases. In others, individuals contacted us directly to share their stories. The 70 cases we reviewed do not represent a random sample of non-citizens with drug convictions who were put into deportation proceedings, but they involve non-citizens from 17 different countries with convictions for possession, distribution, and production of a variety of drugs, obtained under drug laws in 16 states (California, Colorado, Florida, Illinois, Maryland, New York, New Jersey, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, Washington, Wisconsin), in the federal criminal justice system, and in other countries.

We also analyzed data received in response to a Freedom of Information Act request submitted to US Immigration and Customs Enforcement for individualized record data on non-citizens deported for criminal convictions. We examined publicly available data published by other organizations, such as the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, as well as US government agencies, such as the US Department of Homeland Security, US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Interviews were conducted in person or by telephone, and in English, Spanish, Korean, and Cantonese, with an interpreter for the Spanish and Cantonese interviews. All participants were informed of the purpose of the interview and consented orally. No interviewee received compensation for providing information. Where appropriate, Human Rights Watch provided interviewees with contact information for individuals and organizations providing legal, counseling, or other supportive services at the conclusion of the interview. We have used pseudonyms to protect the privacy of certain individuals at their request.

I. Background

US Deportation Policy for Immigrants with Criminal Convictions

In 2007 and 2009, Human Rights Watch published reports documenting how hundreds of thousands of families had been forced apart by punitive and inflexible US deportation policies against non-citizens with criminal convictions, regardless of how minor or old the offense.[4] We found that between 1997 and 2007, of the almost 900,000 non-citizens with criminal convictions who had been deported, 72 percent had been deported for nonviolent offenses. Twenty percent had been in the US legally, often for decades.

Since our reports, the Obama administration has pursued policies that have resulted in a record number of deportations: more than 2.3 million from fiscal years 2009 through 2014.[5] The administration claims its focus is on serious criminals, particularly with regard to enforcement in the interior of the country.[6] According to US government data, the proportion of deportations involving individuals with criminal convictions is at a record high. In fiscal year 2014, 56 percent of removals involved people who had previously been convicted of a crime.[7]

Yet the government’s own numbers indicate that a significant majority of these deportations involve people with convictions for minor and nonviolent offenses. The Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University found that in fiscal year 2013, only 12 percent of all deportees had committed an offense labeled a serious or “Level 1” offense, according to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) definition.[8] The most serious conviction held by half of those who were deported was an immigration or traffic violation.[9]

The increase in deportations, including of those with criminal convictions, was aided significantly by Secure Communities, a program that began in 2008 and was fully implemented throughout the US in 2013, that effectively linked the US immigration enforcement system with local law enforcement activities.[10] In November 2013, DHS announced it was discontinuing the program, and would now request that local law enforcement agencies notify ICE of pending releases of non-citizens convicted of certain priority criminal offenses or believed to pose a danger to national security.[11] The impact of this change is still being evaluated.

Harsh US Drug Policies

Throughout the US, individuals are regularly convicted of possession, production, and distribution of drugs under stringent laws and as a result of aggressive policing and prosecution policies. In 2013, nearly half a million people in the US were in prisons and jails for drug offenses, a dramatic increase from 40,900 people in 1980.[12]

First-time offenders can end up with severe sentences under mandatory minimum sentencing laws for being found with a certain quantity of certain types of drugs, rather than because the evidence shows they played a significant role in drug trafficking.[13] Thus, prosecutors can charge a low-level courier delivering drugs with the same crime as the drug boss who receives the package. The threat of long mandatory minimum sentences can also pressure defendants to plead guilty, rather than risk going to trial.[14]

Drug law enforcement, as documented in several Human Rights Watch reports, is also marked by severe and unjustifiable racial disparities.[15]

Recent Reforms in US Drug Policy

The US continues to spend billions of dollars on drug law enforcement each year, but there is a growing consensus among state and federal legislators and policymakers that harsh criminal sanctions for drug use and distribution may not be the most just, effective, or cost-efficient way to address the societal harms of such conduct.

On a federal level, Congress and the executive branch have enacted reforms that seek to reduce the severely punitive effects of mandatory minimum sentencing laws for drug crimes. In 2010, Congress passed the Fair Sentencing Act to reduce the massive disparity in the amounts of crack versus powder cocaine that triggered mandatory minimum sentences, a disparity that had had a disproportionate impact on African Americans.[16] Since then, federal lawmakers from both the Democratic and Republican parties have called for further reforms. Senator Rand Paul at a 2013 hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee called federal mandatory minimums “a major culprit in our unbalanced and often unjust drug laws.”[17] Attorney General Eric Holder and the US Department of Justice have made several efforts in recent years to minimize the effects of mandatory minimum sentences in the federal system, including instructions to US Attorneys to charge defendants in a way to avoid triggering mandatory minimum sentences and a clemency program for drug convicts serving longer sentences than they would have received under current law.[18]

On a state level, 29 state legislatures have rolled back state mandatory minimum sentencing laws since 2000, and most of them have addressed nonviolent drug-related offenses.[19] Thus, although drug offenders continue to comprise a significant proportion of the US prison population, new commitments of individuals to state prisons for drug offenses decreased 22 percent between 2006 and 2011.[20]

Numerous states, counties, and localities have also created drug courts and other types of diversion programs intended to provide defendants with drug dependency problems opportunities to seek treatment, avoid incarceration, and reduce drug use relapse and criminal recidivism. There are now more than 2,800 drug courts across the US.[21] Some have criticized drug courts for continuing a punitive approach toward drug use[22], but their proliferation reflects some agreement that drug and drug-related offenses may stem from drug dependency requiring treatment as a public health issue, not a criminal one. A few jurisdictions, such as Seattle-King County, Washington, and Santa Fe, New Mexico, have begun to experiment with pre-arrest diversion, in which police have the option to offer community-based services to low-level offenders instead of jail and prosecution.[23]

The changes have been most pronounced with respect to marijuana. Eighteen states have decriminalized possession of small amounts of marijuana, and Colorado, Washington, Alaska, Oregon, and the District of Columbia have legalized recreational use of marijuana altogether.[24] These changes reflect a major shift in US public opinion, with only 45 percent in 2014 opposing the legalization of marijuana, compared to 78 percent in 1991.[25]

II. Immigrants and the “War on Drugs”

Historical Link between US Immigration Policy and Drug Policy

Drug crimes have been deportable offenses since 1922,[26] but the harshest immigration consequences for drug crimes and other offenses came into effect in the 1980s and 1990s, when US legislators began to include immigration regulation as a major component of the so-called “War on Drugs.”

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 enacted harsh mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses, including severely disparate sentences for crack versus powder cocaine. The ADAA of 1986 also authorized the use of “detainers,” under a subsection titled the “Narcotics Traffickers Deportation Act,” by which immigration authorities could request that local law enforcement agencies hold people arrested for controlled substance offenses until they could be taken into immigration custody.[27] These detainers have since been interpreted by DHS to allow for immigration holds on people arrested for a much wider range of offenses, leading to considerable controversy and federal litigation in recent years.[28]

Two years later, the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988 sought to further address “an expansive drug syndicate established and managed by illegal aliens,” in the words of Florida senator Lawton Chiles.[29] The ADAA of 1988 created the concept of the “aggravated felony,” limited at that point to three crimes: murder, firearms trafficking, and drug trafficking. As one law professor put it, “Congress … viewed these crimes as, if not analogous, at least worthy of mention in the same breath.”[30] Those convicted of aggravated felonies were now subject to mandatory detention and fewer procedural rights so as to expedite deportation.[31]

Soon afterward, then-President George H. W. Bush signed the Immigration Act of 1990 into law, declaring that it “meets several objectives of my Administration’s war on drugs and violent crime” and “improves this Administration’s ability to secure the U.S. border—the front lines of the war on drugs.”[32] It eliminated the “Judicial Recommendations Against Deportation,” a provision that had previously allowed sentencing judges to make recommendations against deportation for non-citizens. The 1990 law also disqualified noncitizens with aggravated felony convictions who had served a term of imprisonment of at least five years from 212(c) relief, a now-defunct form of relief from deportation by which legal residents who were deportable for criminal convictions could present evidence of family ties, rehabilitation, and other positive factors to the immigration judge tasked with deciding whether to deport them.[33] The Immigration Act of 1990 also made certain criminal convictions, including those for controlled substance offenses, bars to entering the US.[34]

In 1996, with the passage of the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act and the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, Congress substantially expanded its efforts to deport and bar non-citizens with criminal convictions. It dramatically broadened the definition of an “aggravated felony” to encompass a whole host of minor offenses—capturing offenses as minor as shoplifting and turnstile jumping—and completely eliminated eligibility for relief from deportation through an individualized hearing before an immigration judge for anyone convicted of an “aggravated felony,” regardless of the length of sentence imposed. Congress also significantly broadened the definition of a “conviction” to include dispositions that the criminal justice system does not consider a “conviction,” including convictions that have been expunged, such as those following diversion programs like those offered by drug courts. And it expanded grounds for mandatory detention to include any controlled substance offense (and other non-drug offenses) as well as drug trafficking offenses.[35]

Deportations of Non-Citizens with Drug Convictions

US deportation policy toward immigrants with criminal convictions was shaped initially by concerns about curtailing international drug trafficking. But as the US government’s own numbers show, many of the hundreds of thousands of non-citizens who have been deported for drug offenses over the years have not been engaged in drug trafficking but rather, engaged in more minor conduct.

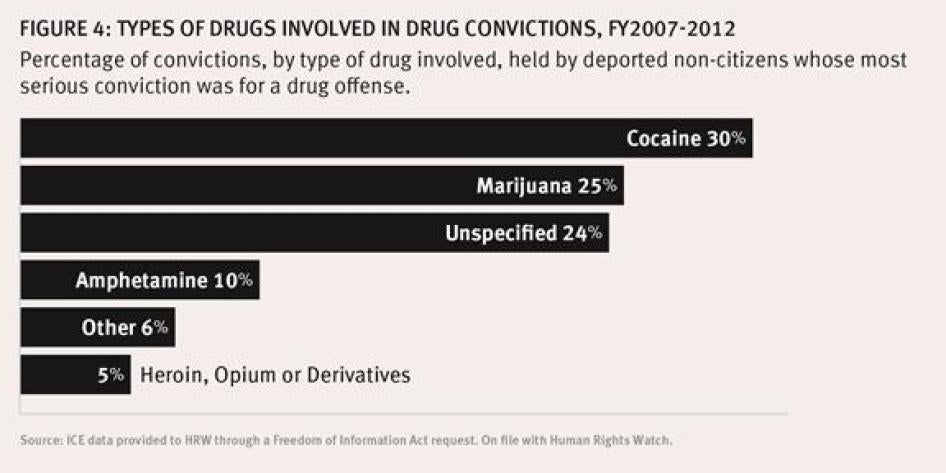

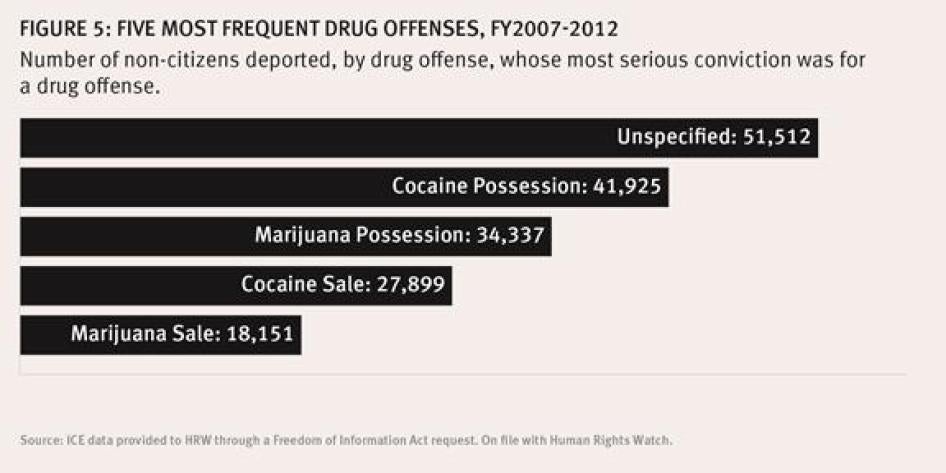

According to data Human Rights Watch received from ICE in response to a request under the Freedom of Information Act, between 2007 and 2012 almost 266,000 deported non-citizens had a drug conviction as their most serious conviction. They constituted one out of every four removals of non-citizens with a criminal conviction. [36]

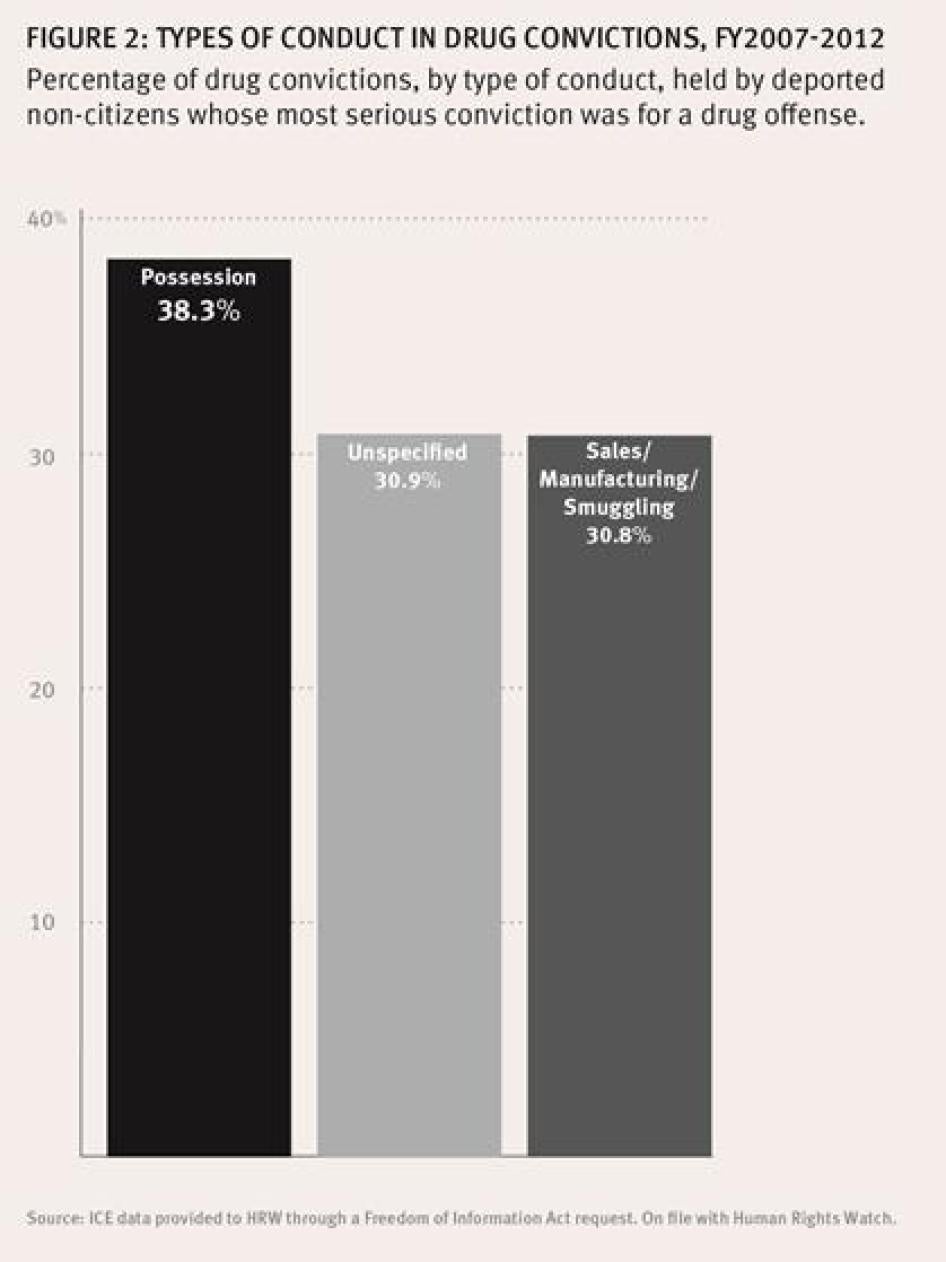

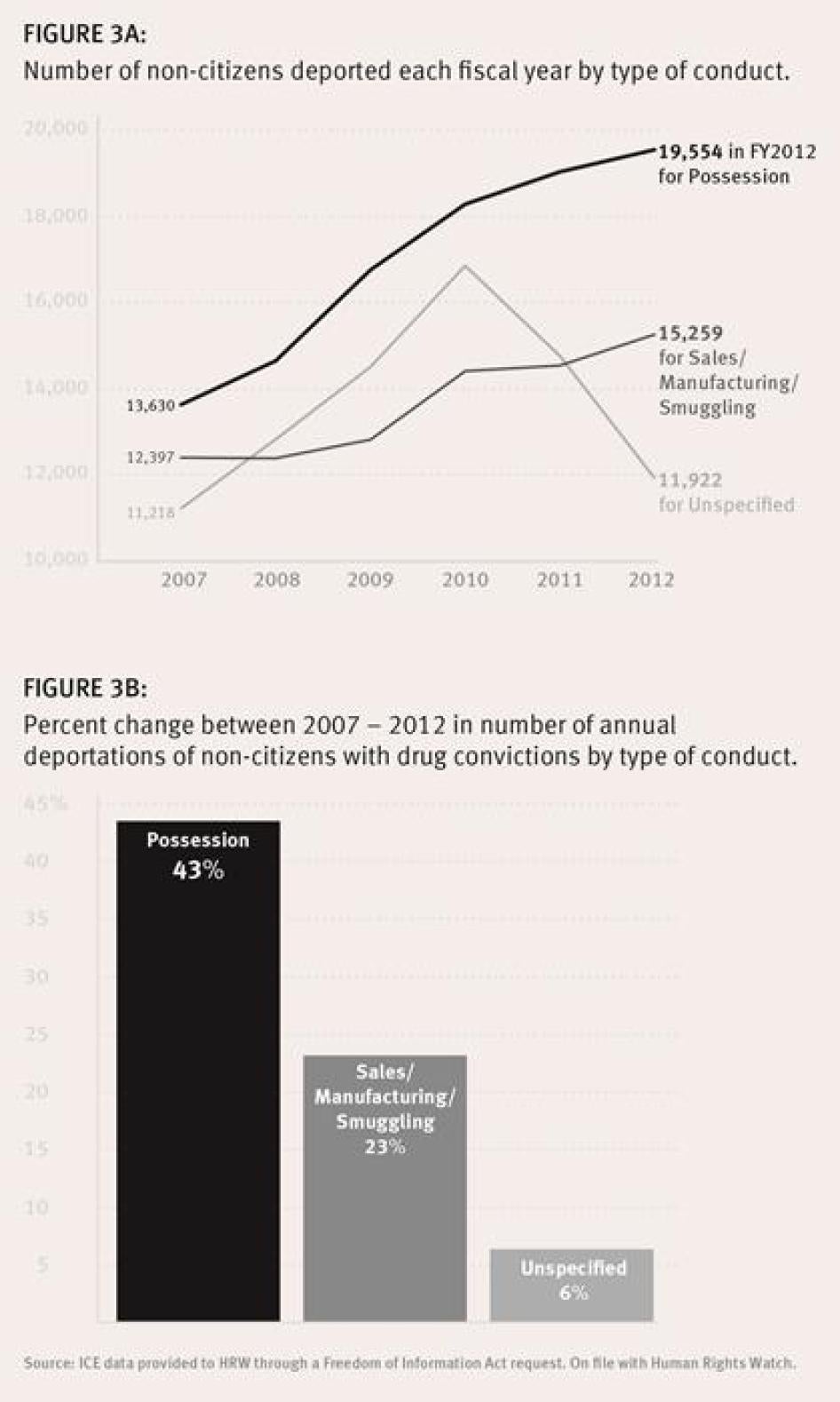

The type of conduct was unspecified in 31 percent of cases, but possession convictions were most common (38 percent), with the remainder involving sale, smuggling, trafficking, and manufacturing.[37] It should be noted that convictions for sale can include low-level sales offenses that often result in little or no prison time in the criminal justice system.

Notably, deportations after drug convictions increased significantly from 2007 to 2012. In particular, deportations after convictions for drug possession increased 43 percent, while deportations after convictions for sales, smuggling, or manufacture increased 23 percent.

In nearly 25 percent of these cases, the drug type was unspecified. Another quarter involved a conviction for marijuana. Over 34,000 deported non-citizens had a marijuana possession conviction as their most serious conviction.

Immigrants’ Perceived Propensity to Commit Crime

Immigrants are sometimes perceived by legislators and the US public as having a greater propensity toward crime than native-born persons. Congressman Lawrence Smith of Florida stated during a 1989 hearing before the House Judiciary Committee that “aliens coming across the border seem to be prone to more violent kinds of crime, more drug-related types of crime,” and that by allowing them to remain in the US, “we are unleashing an army of criminal aliens on American citizens.”[38]

Several studies have shown, however, that foreign-born persons are less likely to commit crimes and less likely to be imprisoned than native-born persons.[39] A 2007 study of California’s adult population in correctional institutions, focusing on males between 18 and 40, found native-born institutionalization rates to be 10 times that of foreign-born immigrants.[40] The same study found that on average, between 2000 and 2005, California cities with a higher share of recent immigrants saw their crime rates fall further than cities with a lower share, particularly with regard to violent crimes.[41] The study concluded, “[s]pending additional dollars to reduce immigration or to increase enforcement against the foreign-born will not have a high return in terms of public safety.”[42]

III. Lawful Permanent Residents Deported for Drug Offenses

There is no publicly available information on how many permanent residents are deported each year for drug offenses. ICE claimed, in response to a 2012 Freedom of Information Act request, not to keep information on the immigration status of those deported on criminal grounds. Numerous interviews with immigrants, their families, and attorneys, make clear, however, that lawful permanent residents are regularly put into deportation proceedings for offenses ranging from marijuana possession to trafficking in cocaine.

“Drug Trafficking” is a Deceptive Label

International human rights law does not preclude a government from deporting non-citizens convicted of serious offenses, such as drug trafficking, after weighing the totality of the circumstances. But US law considers drug offenses that have an element of sale or distribution, even of a small amount of drugs, to be drug trafficking offenses and “aggravated felonies,” triggering severe and permanent consequences.[43] Such convictions make non-citizens, including lawful permanent residents, ineligible for almost all forms of relief from deportation and result in mandatory detention, near-automatic deportation, and permanent exile.

Low-Level Offenses that Constitute Drug Trafficking

Several immigration and criminal defense attorneys told Human Rights Watch that many of their clients who are charged as deportable for drug trafficking had convictions for offenses that are quite minor. As one attorney put it, “I represent a lot of guys with drug trafficking convictions, but I’ve never represented a drug trafficker.”[44]

The definition of “aggravated felony” is overly broad with regard to many offenses, as documented in several Human Rights Watch reports.[45] But while many crimes are considered “aggravated felonies” only if a sentence of one year or more is imposed[46] or other factors are present,[47]all crimes involving sale, distribution, or production of drugs are deemed “drug trafficking” and thus “aggravated felonies.”

Among non-citizens deported for an aggravated felony from 2007 to 2012 who had a drug conviction as their most serious crime, about a quarter (13,000) had a conviction for possession or use of a drug.[48] Although we cannot determine the underlying conduct in these cases, it is likely that many had committed offenses that fall short of what most people would consider drug trafficking.

Erika Pinheiro, a legal services attorney, said many of the immigrant detainees she meets end up with trafficking convictions even if they never sold drugs, because “addicts will buy multiple bags [of methamphetamine]” and then end up charged with possession with intent to sell.[49] And several of the cases reported to Human Rights Watch involved defendants who claimed that they had not known about the drugs they allegedly possessed.[50] Andrew Free, a private immigration attorney, described a case in which his client, a lawful permanent resident who lived near the Mexican border in Texas, was convicted of possession with intent to distribute because he was hired to drive a truck in which a large amount of marijuana was found. There was strong evidence to support his claim he did not know there were illicit drugs in the truck, but Free said, “You can still be convicted of possession with intent to distribute marijuana despite the fact that the government can't prove you knew the type and amount of contraband in the vehicle you're driving.”[51]

Robert Jaeggli, an attorney in Washington, reported that one of his clients had been prescribed pain medication, did not like it, and gave it away with no remuneration. But he was convicted of attempted delivery of a controlled substance. “When he was caught by the police, he confessed to the activity because he had no idea he wasn’t supposed to be doing that,” Jaeggli said. His client was in his 60s, had lived in the US as a green card holder since the 1970s, had his entire family living in the US, and had no other criminal record. His client was able to withdraw his guilty plea and enter a new plea to solicitation, which does not constitute “drug trafficking,” and Jaeggli is hoping on that basis to terminate deportation proceedings. But in the meantime, his client spent six months in immigration detention, during which time he lost his job, his apartment, and almost everything he owned.[52]

In a case published in Politico Magazine, Howard Bailey, a veteran of the Persian Gulf War, claimed he had been convicted for possession of marijuana with intent to distribute after he accepted some packages in the mail for an acquaintance. Ten years later, in 2012, he was deported to Jamaica, while his US citizen wife and two US citizen children remain in the US.[53]

In many of the cases reported to Human Rights Watch, permanent residents facing deportation for their drug trafficking conviction had convictions so minor, the judges in their criminal cases had sentenced them to little or no time in prison.

- Lundy Khoy, a refugee from Cambodia and a permanent resident, said she was convicted of possession with intent to distribute when, as a college student, she was arrested with ecstasy pills her boyfriend gave her. The criminal justice system imposed a punishment of three months’ imprisonment and four years’ probation, but because that conviction constituted “drug trafficking” and thus an “aggravated felony,” she has been ordered deported. She remains in the US only because Cambodia has not issued a travel document for her.[54]

- “Mario F.,” a lawful permanent resident from Colombia, was stopped at the airport in February 2013 and put into removal proceedings for a single 10-year-old conviction for sale of methamphetamine for which he received only probation.[55]

Deported for a Ten-Year-Old Cannabis ConvictionRaul Valdez, a 36-year-old lawful permanent resident, moved to the US when he was one year old and grew up in the suburbs of Chicago. His entire family lives in the US. They are US citizens and permanent residents. But in 2014, Valdez was deported for a 2003 conviction for unlawful possession of cannabis with intent to deliver. Speaking by phone from Guadalajara, Mexico, Valdez told Human Rights Watch that he used to smoke marijuana, but said he had not been a dealer. However, when his brother’s friend got in trouble, “he told on me, and they found the drugs in my house.” His criminal defense attorney did not tell him he could get deported. After Valdez pled guilty, he was sentenced only to 60 days in prison and 2 years’ probation. Ten years later, however, immigration came and arrested Valdez. “They picked me up out of nowhere,” he said. He said immigration agents told him, “We’re deporting people with drug convictions.” Valdez was placed in immigration detention, where he remained for over two years as he fought to stay in the country he considers home. According to family members who submitted affidavits on his behalf, Valdez, who also had misdemeanor convictions from his teenage years, had turned his life around since his earlier brush with the law. Valdez had a union construction job that paid well, and his employer praised his work in a letter submitted to immigration authorities. He provided financial and emotional support to his elderly parents. He was engaged to a US citizen, who attested, “My children [from a previous marriage] see Raul as a father figure and know he is someone they can always count on.” But Valdez’s conviction constituted drug trafficking and an “aggravated felony.” As such, the immigration judge could not consider the minor nature of his conviction, evidence of his rehabilitation, and his strong ties to his family and the US, but instead had to order him removed. His pro bono attorney sought a grant of prosecutorial discretion, citing all the positive factors in his case and the fact that his last conviction was over 10 years old. The US government denied his request, and Valdez now lives in Mexico, a country he barely knows.[56] |

Facing Deportation and Family Separation for a Teenage Drug Offense

Abdulhakim Haji-Eda and his US citizen wife, Hani Hamza, and their two children, Haroun (left) and Nasreen, also US citizens. Haji-Eda, a refugee from Ethiopia, has been ordered deported as a drug trafficker for a single conviction for selling a small amount of cocaine at the age of 18. Now 26, he has no other convictions and is seeking a stay of removal to remain in the US with his family. © 2015 Private Abdulhakim Haji-Eda was born in Ethiopia but grew up in a refugee camp in Kenya. When he was 13 years old, he and his family came to the US as refugees and settled in Seattle, Washington. He said he struggled academically, but he loved basketball and as a teenager, he and his friends set up a basketball league for local Muslim youth, with the goal of being mentors and helping them keep out of trouble.[57] When he was 15 years old, Haji-Eda’s father kicked him out of their house because he had gone to Oregon for a basketball game without asking his father’s permission. Haji-Eda went to live with a cousin, who told him, “I can’t buy you food every day, go sell [drugs].” According to Haji-Eda, he tried hard to find another job and did stop selling drugs when he was briefly able to live with a girlfriend’s family, but he eventually had to return to his cousin’s home. “It’s not something that I chose,” he said, “It’s something that for me was to survive.” In 2006, days after he turned 18, Haji-Eda was arrested for selling a small quantity of cocaine at a bus stop in downtown Seattle. He was ultimately convicted of possession with intent to manufacture or deliver and sentenced to one year in prison, of which he served six months. Haji-Eda said his criminal defense attorney gave him no warning that pleading guilty could result in the loss of his legal status and permanent deportation. But at the end of his six-month sentence, immigration authorities arrested Haji-Eda. He was put into removal proceedings and charged with being deportable for the aggravated felony of drug trafficking.[58] Now a soft-spoken 26-year-old, Haji-Eda is married to Hani Hamza, a US citizen, and they have two US-born children, a three-year-old son and a two-year-old daughter. His parents are US citizens, as are all his brothers and sisters. Haji-Eda has worked steadily since his arrest, and he has no other criminal conviction. But because his conviction is considered an aggravated felony, the immigration judge could not consider these factors, and ultimately ordered him deported. Lori Walls, his current immigration attorney, pointed out, “The judge in his criminal case…sentenced him to the extreme low-end. The flexibility that’s available in criminal court is not there in the immigration court.”[59] Haji-Eda currently remains in the US only because the US government temporarily granted a stay of removal, but it expired in August 2014 and his status remains in limbo. Hamza, Haji-Eda’s wife, has heard President Obama claim he is focusing on deporting serious criminals. On paper, she understands that her husband would be seen as a drug trafficker and as one of these serious criminals. But if she could meet President Obama, she told us, she would say to him: “Are you sure you know what you’re talking about? Why don’t you sit down and talk to him? Why don’t you meet him? Why don’t you meet his family?”[60] |

Not every non-citizen with a conviction for “drug trafficking” receives an insignificant prison sentence. Human Rights Watch interviewed several people with more serious drug trafficking convictions, including people who had convictions for manufacturing methamphetamine, cultivating marijuana, and trafficking in crack cocaine, who had been sentenced to considerably more time. In some of these cases, however, the defendants were sentenced under the kind of disproportionately harsh mandatory minimum sentencing laws that are currently being reexamined at both the state and federal level. To immigrants who have served these long sentences, deportation only further compounds the harshness of the punishment.

The Difference an Individualized Hearing Can Make

Before the 1996 amendments to immigration law, lawful permanent residents convicted of aggravated felonies, including drug trafficking, were still able to get an individualized hearing before an immigration judge where they could present evidence of their family ties, residence in US, rehabilitation, and other factors in favor of their application to remain in the US. This relief, called “212(c)” for its provision number in the Immigration and Nationality Act, was available before 1990 to all permanent residents with any aggravated felony conviction, and before 1996, to all permanent residents with an aggravated felony conviction if they had received criminal sentences of five years or less.[61] After protracted litigation around whether the 1996 amendments should be applied retroactively to those who were convicted before 1996, the Supreme Court ruled that certain lawful permanent residents who pled guilty before 1996 are still eligible for 212(c) relief.[62] Almost 20 years after these amendments went into effect, there are still permanent residents who are eligible for 212(c) relief because they are still being arrested by immigration authorities for their pre-1996 convictions.

The case of “Luis A.,” reported to Human Rights Watch by his son Jorge, illustrates how eligibility for such an individualized hearing, rather than the imposition of a one-size-fits-all policy, can make all the difference for a lawful permanent resident and his family.[63]

Luis first came to the US in 1966, and eventually raised four children, all US citizens, with his wife, also a US citizen. He was a farmworker for many years in the Central Valley of California, and now runs a popular stand at a local farmers’ market.

But in 1989, Jorge said, his father was approached by an undercover police officer who told him he had a very ill father and needed to obtain drugs to try to make money to help his dad. “My dad had been working in [his town] since the 1960s, and he knew the good, the bad, and the ugly,” he said. He connected the undercover police officer to some of these contacts, and Luis was soon afterward arrested, convicted, and sentenced to one year in prison for possessing and transporting cocaine.

Although that year of imprisonment was hard on the entire family, they thought they had put this conviction behind them, as Luis never got in trouble again. Jorge said, “He never even got a parking ticket.” But in 2009, 20 years later, immigration authorities arrested his father and put him in immigration detention in Eloy, Arizona, and placed him in removal proceedings.

Because his father had been convicted in 1989 and released from his prison sentence before October 1998,[64] he was not subject to mandatory detention for his drug crime and he was still eligible for 212(c) relief, even though his conviction constitutes an “aggravated felony” under current law. The government did not contest it and the judge granted him relief immediately. Soon afterward, Luis applied for and was granted naturalization.

Luis is still scarred by his experience of six weeks in immigration detention. He developed a thyroid condition and high blood pressure in detention and suffered from depression. He is uncomfortable in crowds and he refuses to stay at parties or gatherings for more than an hour. But they know they were lucky that Jorge, who has a law degree, was able to obtain good counsel and navigate the complex immigration system to get his father released and eventually end his ordeal.[65]

US Supreme Court Response to Unjust Interpretations of “Drug Trafficking”

Over the years, the very broad definition of “drug trafficking” used by the US government has led to protracted litigation, often involving long-term lawful permanent residents facing deportation for minor offenses. Although permanent residents with low-level offenses continue to be placed in proceedings as drug traffickers, Supreme Court decisions have placed some limits on the US government’s interpretation of drug trafficking.

In 2006, the Supreme Court heard a challenge by Jose Antonio Lopez, a permanent resident whom the US government sought to deport as a drug trafficker for a single conviction in South Dakota for aiding and abetting another person’s possession of cocaine. This offense would have been treated as a misdemeanor under federal law, but South Dakota, like many states, categorized this crime as a felony. The Court ruled that a state felony conviction for possession of a controlled substance is not a drug trafficking aggravated felony if the same offense would be punishable only as a misdemeanor under federal law.[66]

Since then, the Supreme Court has further rejected the US government’s interpretation of “drug trafficking” to include a second or subsequent conviction for simple possession of a controlled substance (Carachuri-Rosendo v. Holder),[67] and ruled that a conviction for an offense that could include social sharing cannot be considered “drug trafficking” (Moncrieffe v. Holder).[68]

These rulings have allowed some permanent residents in deportation proceedings to argue against deportation and apply for cancellation of removal, and thereby present evidence of their strong ties to the US. Other Supreme Court decisions have also expanded options for some lawful permanent residents with old convictions.[69] But in the meantime, there are likely thousands of permanent residents, if not more, who have been deported as aggravated felons for offenses that are no longer considered “aggravated felonies,” or who have otherwise been deported under incorrect interpretations of US law.

Once deported, it is extremely difficult for such former residents to come back to the US legally. It is not enough for them to show that they were deported under incorrect interpretations of the law. They must meet strict time, number, and procedural requirements to reopen or reconsider their cases.[70] Once deported, US government regulations state that they can no longer file a motion to reopen or reconsider. Although some courts have found that these requirements and bars do not apply in certain situations,[71] reopening a case is a complex procedure that is practically impossible for an immigrant who has been deported to navigate, particularly without an attorney. According to Jessica Chicco, staff attorney at the Post-Deportation Human Rights Project at Boston College, “[F]or many people, if they’re not in a position to file a motion to reopen in 90 days [of their removal order], they’ll have a very difficult time.”[72]

For example, Marco Merino, a permanent resident who came to the US from Chile when he was five months old, was unable to reopen his case after being deported in 2007 for two possession convictions, one for a marijuana joint and one for LSD, convictions he received when he was 18. According to Merino, these convictions were so minor, “I never received one day in jail.”[73] But over 10 years later, when he returned from traveling abroad, he was placed in immigration proceedings and eventually deported under the interpretation the Supreme Court later held was incorrect in Lopez.[74] The Post-Deportation Human Rights Project took Merino’s case after he was deported, but the Fifth Circuit US Court of Appeals ruled in 2012 that Merino did not meet the strict procedural requirements to reopen his case and seek a legal way to return.[75]

Deportation for Simple Possession Offenses

Lawful permanent residents can be deported for any drug offense, including simple possession (other than a conviction for possession of a small amount of marijuana).[76] However, permanent residents with simple possession convictions can try to avoid deportation by applying for “lawful permanent resident cancellation of removal” if they meet certain requirements for length of residency and lawful status,[77] and get the kind of individualized hearing permanent residents with drug trafficking convictions are denied.

According to several dozen immigration lawyers interviewed by Human Rights Watch, many of their permanent resident clients who are put in deportation proceedings for simple possession offenses are able to win cancellation of removal. However, in the meantime, most are placed in mandatory detention while proceedings are pending, which can take months or even years, during which time many lose their jobs and their homes. They must navigate the complexities of a deportation proceeding in which they have no right to a court-appointed lawyer if they cannot afford to pay for one themselves. (More information on the human rights impact of mandatory detention for drug offenses can be found in Section IV of this report.)

Some permanent residents are not eligible for cancellation of removal because they do not meet the strict residency and status requirements, despite having lived in the US for many years and having strong family and community ties.

For example, Iris del Carmen Morales, a grandmother and a lawful permanent resident from Guatemala, told Human Rights Watch in 2014 while in immigration detention that she was ineligible for cancellation of removal, even though she has lived in the US since 1989, because her 2013 conviction for possession of methamphetamine occurred just three days before she would have accrued the required seven years of lawful status. Morales has five children, four of whom live in the US and are citizens or permanent residents. She became dependent on drugs, she said, after she lost her job and her home and began hanging out with “the wrong people.” Morales said the judge agreed to send her to a drug treatment program, but instead of starting the program after her six-month sentence, she was arrested by ICE and put into removal proceedings.[78]

Eswin Figueroa Lemus, a lawful permanent resident from Guatemala who had lived in the US since 1990, told Human Rights Watch he was facing imminent deportation for being found with a very small amount of cocaine. Figueroa claimed he was not a drug user but had accepted the drug from an acquaintance. He had built a life with his wife and three US citizen children, working in construction and paying taxes for over 20 years. “I’m not a drug addict,” Figueroa said. “I don’t know why I took it, why I saved it.…my mistake with the drug has cost me my family.”[79] Despite his 20-plus years in the US, Figueroa had only been a permanent resident since 2006, and his 2012 conviction cut off his eligibility for lawful permanent resident cancellation of removal.

Lawful permanent residents are also ineligible for cancellation of removal if they previously were granted cancellation of removal or 212(c) relief, a similar form of relief that existed before the 1996 amendments. Persons who struggle with drug dependency often relapse after initial efforts at drug treatment. The consequences of such relapse for permanent residents are severe.[80]

Marion Scholz, a lawful permanent resident from Germany who has lived in the US for almost 50 years, was deported in 2014 after two misdemeanor convictions for possession of methamphetamine. Scholz said she had struggled with dependency on methamphetamine for many years. She was first convicted of misdemeanor possession of a controlled substance in 1993. When the government sought to deport her in 1998, Scholz applied for and received a grant of cancellation of removal. She sought treatment and was off drugs for four months, but fell back into drug dependency and was convicted again in 2005 for possession, which led to new deportation proceedings.

After almost two years in immigration detention, ICE released Scholz in 2010 with an ankle monitor, and she immediately entered a drug treatment program. According to Scholz and her attorney, she turned her life around completely. She has been off drugs for over six years, and she was promoted at the job she had before getting deported. She repaired relationships with her family, including a son, all US citizens. But she was nevertheless deported to a country where she does not speak the language and knows no one. She is now living in a shelter. Scholz wishes the US government could “understand what addiction is,” and “look at what [people are] doing now to better themselves.”[81]

Immigration Arrests for Old Offenses

The US immigration law makes no distinction between drug offenses committed recently and drug offenses committed many years ago. Human Rights Watch documented numerous cases in which immigrants with old convictions for drug offenses were put into removal proceedings in recent years.[82]

In some cases, permanent residents traveled abroad and their convictions were flagged by US Customs and Border Protection upon their return, or they applied for naturalization or some other immigration benefit, not knowing their convictions could lead to their deportation. For example, “Mario F.,” a lawful permanent resident from Colombia, was put into removal proceedings in 2013, upon returning to the US from a trip abroad, for a 2003 conviction for sale of methamphetamine.[83] “Luis A.” (case described above) believed he was put into removal proceedings in 2009 for a 1988 conviction because he had applied to renew his green card.[84] Henry Cruz stated one client, a 63-year-old Korean woman with a ten-year-old conviction for using communication devices to assist in drug trafficking, was put into removal proceedings after she applied for naturalization.[85]

Advocates reported some people are identified through traffic stops or more recent arrests, often for minor, non-deportable offenses.[86]

Some immigrants and immigration advocates reported immigration authorities actively sought out individuals at their homes or at work, years after their criminal conviction. ICE officials came to Raul Valdez’s home almost 10 years after his 2003 conviction for possession of cannabis with intent to deliver, leading to his deportation in 2014.[87] Ricardo Fuenzalida reported that immigration authorities came to his home in 2013 to put him in detention and removal proceedings for two marijuana possession convictions 13 years earlier.[88] Talia Peleg and Ruben Loyo, immigration attorneys at Brooklyn Defender Services, described cases in which lawful permanent resident clients with possession convictions had been arrested at home years after their convictions.[89] Similarly, Erika Pinheiro at Esperanza Immigrant Rights Project in Los Angeles recounted a case in which immigration authorities had shown up at her client’s door years after his one 1998 conviction for sale of marijuana.[90]

In Preap v. Johnson, three non-citizens in 2014 brought a federal habeas corpus class action lawsuit against DHS in California challenging their mandatory detention based on the fact that all three had been arrested by immigration officials five to ten years after their relevant convictions.[91] All three plaintiffs have convictions for drug offenses, in addition to other offenses.[92] Since the lawsuit was filed, the court has granted plaintiffs’ motion for class certification and granted their motion for a preliminary injunction requiring the government to give them bond hearings.[93] Similar challenges have been brought and granted in several district courts across the country.[94]

It should be noted that the most recent enforcement priorities memorandum issued by DHS Secretary Jeh Johnson states “extended length of time since the offense of conviction” will be considered, along with other factors, in determining whether prosecutorial discretion should be exercised even when the past criminal conviction makes the case an enforcement priority.[95]

Fearing Deportation for Being in the Wrong Place at the Wrong Time 20 Years Ago“Daniel P.,” now 42, is a social worker, husband, and father to three children. His wife, children, mother, and sister are all US citizens. Daniel is a lawful permanent resident who has lived in the US since he moved from the Dominican Republic at the age of seven. He has been at the same job for 14 years, as an employee of the City of New York. Although Daniel is proud of his work and his family, he said, “Since 1996, my life has been a nightmare.” In 1996, when he was 23 years old, Daniel pled guilty to criminal sale of a controlled substance in the third degree, his sole conviction. Daniel claimed he “was in the wrong place at the wrong time.” He had stopped to say hello to some friends hanging out on the street, he said, on his way home from work. He did not know the police were watching his friends, who were selling drugs. They arrested everyone, and even though no drugs were found on him, Daniel was charged with conspiracy to sell drugs. His attorney told him that if he pleaded guilty, he would not get a prison sentence, and he was right. Daniel was sentenced to five years’ probation and a $155 fine. Daniel said he met all the terms of his probation. One of his probation officers noticed that he was always on time, and he recommended he apply for a certificate of relief from disabilities. In New York, such certificates are meant to “contribute to the complete rehabilitation of first offenders and their successful return to responsible lives in the community.”[96] Daniel received the certificate, went to college and graduate school, and continued with his life. Soon afterward, though, Daniel heard news reports that permanent residents like him were being deported for criminal convictions. Since then, he has not traveled outside of the US for fear that he will be stopped at the airport and put into removal proceedings. When his father died in the Dominican Republic, he was unable to go to the funeral. He has not been able to visit his 87-year-old grandmother and 105-year-old great-grandmother for almost 20 years. Daniel said, “This type of law is breaking up families, destroying families.”[97] |

Permanent Exile and Bars to Reentering the US

Those who are deported have no legal way to return, and no matter how many years have passed without a new arrest, they are forever barred from returning to live in the US with their families.

Carlos Guillen, a lawful permanent resident from Ecuador, was arrested in 1992 in Texas for possession of drugs with intent to distribute after police found a large amount of cocaine in his home. His brother has since admitted the drugs belonged to him, but Guillen went on to serve seven years in prison and was deported to Ecuador in 1999. After being separated from his US citizen wife and three US citizen children for 15 years, and suffering from serious medical conditions, his daughter Diana Wride reported that her father, now almost 70 and desperate, tried to reenter the US illegally. Because it had been over 20 years since the date of the offense, and it was Guillen’s only conviction, his daughter applied for prosecutorial discretion so her father could spend his remaining years with his family. Their application was denied.[98]

Many of those who do return illegally face criminal prosecution for the federal crime of “illegal reentry” and additional time in prison with sentences that are enhanced by their prior drug convictions. Among defendants convicted and sentenced for felony reentry or second or subsequent illegal entry in 2013, more than 3,000 or 17 percent had a prior conviction for a drug offense.[99]

Jesus Octavio Perez Ochoa, according to federal court documents filed by his federal public defender, grew up in the US with his entire family. He was deported in 1993 after a conviction for distribution of cocaine, although he was using and sharing drugs, not selling them. He had pled guilty on the advice of his criminal defense attorney who assured him he would only receive a sentence of probation. Perez Ochoa returned illegally to the US and was living quietly with his permanent resident wife and their US-born daughter when he was the victim of a hit-and-run accident and waited for the police to arrive. He was then arrested and transferred to immigration authorities.[100] Sixteen years after his drug conviction, Perez Ochoa was prosecuted for illegal reentry and sentenced to 13 months in prison.[101]

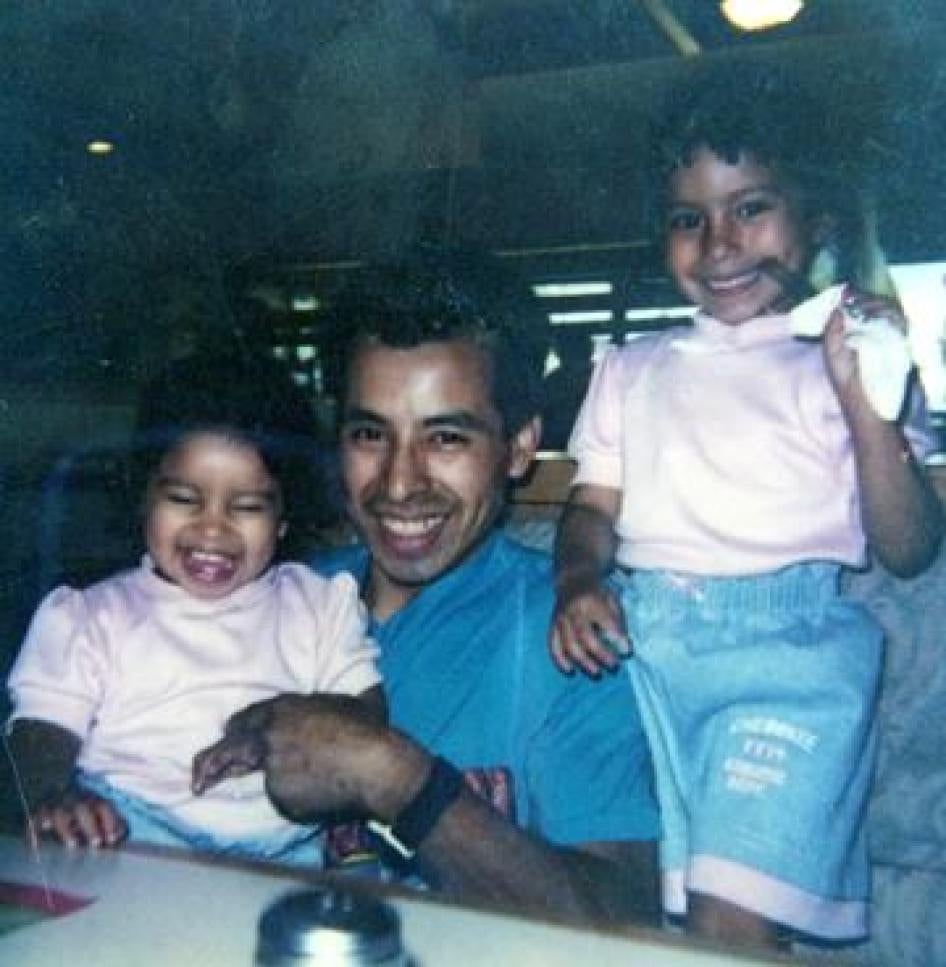

“This is All from One Mistake, One Poor Choice He Made.”

Francisco Equihua Lemus, with his two US-citizen daughters, Lili (left) and Cecilia in 1993. Equihua was deported in 2001 after a conviction stemming from manufacture of methamphetamines. According to his daughters, he reentered illegally and lived without incident for nine years. When Equihua was stopped for a broken taillight in 2010, he was deported again. Francisco Equihua Lemus was first deported in 2001 after a conviction stemming from manufacture of methamphetamines. According to his US citizen daughters, Cecilia and Lili Equihua, Francisco first came to the US in 1967 and had been a lawful permanent resident. Separated from their mother but devoted to his two young daughters in the US, Francisco came back illegally soon after his deportation. Cecilia and Lili, now 24 and 22 years old, said he lived a quiet life for nine years, dedicated to spending time and rebuilding his relationship with his daughters. The sisters remembered “Sunday was father day.” They lived with their mother in Las Vegas, Nevada, while their father lived in California. So every Sunday, he would leave California at 4 am to be in Las Vegas by 8 am. He would wake them up, take them to church, and then go to lunch or the movies. He would leave at 5 pm so he could be home in time to go to work early Monday morning. The sisters saw him sacrifice as much as possible for their sakes—their father lived for them. Even their mother came to respect and appreciate him because he provided as much financial support as he could. In 2010, the Sundays came to an end. Cecilia remembered he had come to take them shopping for school. “We had such a good time, it was almost painful to see him leave.” He began driving back to California and two hours later, she called him, as she always did, but there was no answer. Cecilia stayed up all night calling him and heard nothing. Two weeks later, they finally heard from their father. He had been stopped for a broken taillight, taken to immigration detention, and immediately deported. He was only able to get in touch with them once he was back in Mexico. A week or so later, Francisco tried to enter the US illegally again. He was caught and prosecuted for felony illegal reentry and sentenced to two years in prison, which he served in New Mexico. In 2012, Francisco was deported again. His daughters worry for his safety in Mexico because of drug cartel violence, but they hope he will stay in Mexico and out of US prison. Cecilia and Lili understand their father committed a serious crime, but they feel that their family is continuing to be punished for one poor decision he made years ago. They long for a way for their father to come back to the US legally, so he can be here for their graduations and other milestones. Lili said, “There are still so many things he could be a part of.”[102] |

IV. Permanent Denial of Legal Resident Status

The “Controlled Substance” Bar

The US, like many countries around the world, bars non-citizens from gaining legal resident status if they have certain criminal convictions, including drug offenses. A state may legitimately consider the existence of convictions in determining who may or may not reside within its borders, particularly as a long-term immigrant. The draconian nature of the bar for any controlled substance offense, however, stands out because of the severe impact it has on the ability of affected immigrants to live with their US citizen families in the US. And given the changes in how the criminal justice system views drug offenses, the bar seems increasingly arbitrary.