“I would beat her,” the Algerian man confirmed, “not hard, just normal.” His response to the question, “Would you beat your wife?” aired on Ennahar, an Algerian TV channel in March, alongside several similar answers. sparked outrage on social media.

The show betrayed an acceptance of domestic violence among many Algerians that contributes to abuse and can prevent survivors from getting help. Domestic violence survivors interviewed for a recent Human Rights Watch report spoke of being beaten, burned, and stabbed by their partners. Some also said their husbands prevented them from working or from seeing friends or family.

When women sought help they often faced formidable barriers instead of aid. Their families often refused to help. Police turned them away or did little to investigate their complaints. Many could not find a shelter or other emergency assistance.

In December 2015, Algeria’s Parliament adopted Law no.15-19, criminalizing some forms of domestic violence in its Penal Code, while Tunisia and Morocco continue to debate draft laws on violence against women.

Though Algeria was first to legislate reforms, it’s law is not strong enough. Positive changes include increased penalties for assault against a spouse, or members of the family, and criminalization of psychological and economic violence against spouses.

Tunisia’s and Morocco’s current Penal Codes provide increased penalties for assault against certain members of the family, but do not criminalize psychological and economic forms of domestic violence. However, the Tunisian and Moroccan draft laws on violence against women go further than Algeria’s law by providing a broad definition of violence against women that includes physical, psychological, economic, and sexual violence, and by criminalizing forms of domestic violence other than assault.

Algeria’s penal code reforms also contain loopholes, allowing convictions to be dropped or sentences reduced if victims pardon their abusers. Human Rights Watch research found that women in Algeria, as in many other countries, face strong social and economic pressure to pardon their abusers, limiting the effect of the law.

The Algerian law, like Morocco’s penal code and draft law, also relies excessively on assessments of physical incapacitation to determine the level of sentencing, without offering guidelines for forensic doctors on how to determine incapacitation in domestic violence cases. The law ignores that harm resulting from domestic violence may be the result of several beatings that cannot be assessed in a single forensic examination, or non-visible harm such as brain trauma, stress-related disorders, emotional abuse and isolation that does not leave a physical mark.

“Hassiba” who suffers from paralysis of her left arm and leg, is a case in point. She said her condition was caused by a brain injury after her husband threw a chair at her head. However, the courts sentenced her husband only to two months in prison and a fine of 8000 DZD (US $73). They treated it as a minor offense because they relied on the report by the forensic doctor, who determined that her injuries from the attack to her head had caused only 13 days of incapacitation despite medical exams earlier that day which she said showed that some nerves in her brain were damaged and that, as a result, she had been paralyzed in her left arm and leg. Under the penal code, stiffer penalties begin with 15 days of incapacitation, as determined by a forensic doctor; and injuries that lead to a permanent disability can result in prison terms of up to 10 years which now under Law no.15-19 has increased to 20 years.

The Algerian law focuses on criminalization. But further reforms should follow the example of Tunisia’s draft law, currently before its Parliament, which includes the key elements of prevention, protection, and prosecution in combating domestic violence.

Protection orders (also known as temporary restraining orders), for instance, have been shown around the world to be a useful way to prevent further violence. Such orders can require the suspected offender to leave the family’s home, stay away from the victim and their children, surrender weapons, and refrain from violence, threats, damaging property, or contacting the victim. Algeria provides no such protection, leaving women exposed to violence and threats of retaliation if they seek help.

Tunisia’s draft law provides for both immediate protection by removing a suspected abuser from the home, and longer-term protection orders that are not dependent on a criminal case or divorce proceedings.

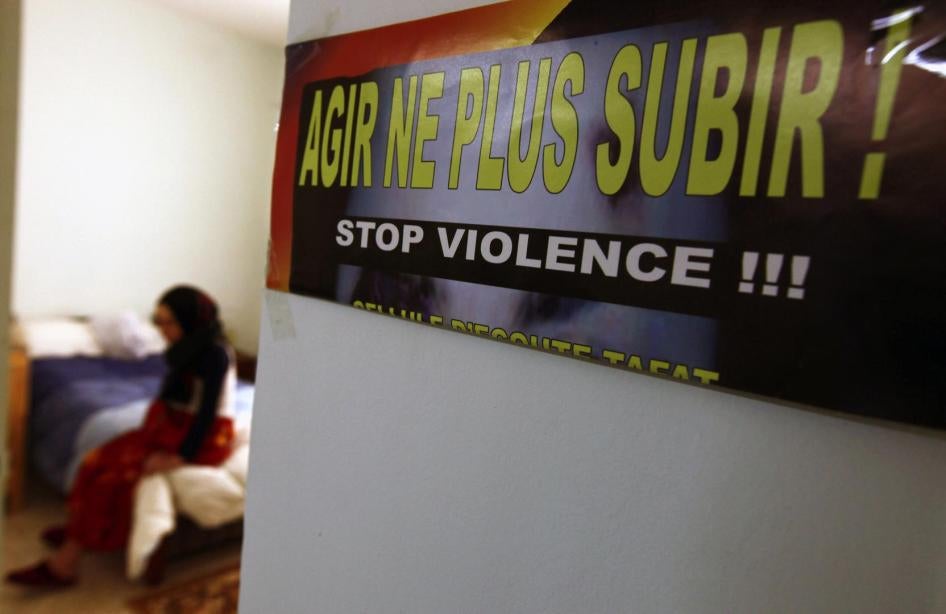

Algerian Law no.15-19 is also silent on shelters and assistance for domestic violence survivors. The country of 41 million people has only three state-run shelters specifically for women victims of violence. The government instead leaves it to non-governmental organizations to run shelters, and these are scarce, underfunded, and concentrated in urban areas.

Algeria may be eclipsed very soon by its neighbors in adequately preventing domestic violence, protecting survivors, and prosecuting abusers. The government should stand up for women and fight violence in the home. This includes ensuring that police and prosecutors are trained and motivated to investigate and prosecute cases of domestic violence. The government should also help victims reach safety, including in emergencies, by introducing a law for protection orders and funding domestic violence shelters.

Taking these actions, along with public awareness campaigns that emphasize zero tolerance for domestic violence, are a critical step to changing the attitudes showcased in the TV program.

Beating women should never be considered “normal.”