As the Senate considers the USA Freedom Act this week, policymakers should strengthen it by limiting large-scale collection of records and reinforcing transparency and carrying court reforms further. The Senate should also take care not to weaken the bill, and should reject any amendments that would require companies to retain personal data for longer than is necessary for business purposes.

It has been two years since the National Security Agency (NSA) whistleblower Edward Snowden unleashed a steady stream of documents that exposed the intention by the United States and the United Kingdom to “collect it all” in the digital age. These revelations demonstrate how unchecked surveillance can metastasize and undermine democratic institutions if intelligence agencies are allowed to operate in the shadows, without robust legal limits and oversight.

On May 13, the US House of Representatives approved the USA Freedom Act of 2015 by a substantial margin. The bill represents the latest attempt by Congress to rein in one of the surveillance programs Snowden disclosed—the NSA’s domestic bulk phone metadata collection under Section 215 of the USA Patriot Act. The House vote followed a major rebuke to the US government by the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, which ruled on May 7 that the NSA’s potentially nationwide dragnet collection of phone records under Section 215 was unlawful. Section 215 is set to expire on June 1 unless Congress acts to extend it or to preserve specific powers authorized under the provision, which go beyond collection of phone records.

Surveillance reforms are long overdue and can be accomplished while protecting US citizens from serious security threats. Congress and the Obama administration should end all mass surveillance programs, which unnecessarily and disproportionately intrude on the privacy of hundreds of millions of people who are not linked to wrongdoing. But reforming US laws and reversing an increasingly global tide of mass surveillance will not be easy. Many of the programs Snowden revealed are already deeply entrenched, with billions of dollars of infrastructure, contracts, and personnel invested. Technological capacity to vacuum up the world’s communications has outpaced existing legal frameworks meant to protect privacy.

The Second Circuit opinion represents an improvement over current law because it establishes that domestic bulk collection of phone metadata under Section 215 of the Patriot Act cannot continue. Section 215 allows the government to collect business records, including phone records, that are “relevant” to an authorized investigation. The court ruled that the notion of “relevance” could not be stretched to allow intelligence agencies to gather all phone records in the US.

However, the opinion could be overturned and two other appeals courts are also considering the legality of the NSA’s bulk phone records program. The opinion also does not address US surveillance of people not in the US. Nor does it question the underlying assumption that the US owes no privacy obligations to people outside its territory, which makes no sense in the digital age and is inconsistent with human rights law requirements.

Even if the Second Circuit opinion remains good law, congressional action will be necessary to address surveillance programs other than Section 215—both domestic and those affecting people outside the US—and to create more robust institutional safeguards to prevent future abuses. The courts cannot bring about reforms to increase oversight and improve institutional oversight on their own.

Human Rights Watch has supported the USA Freedom Act because it is a modest, if incomplete, first step down the long road to reining in the NSA excesses. Beyond ending bulk records collection, the bill would begin to reform the secret Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) Court, which oversees NSA surveillance, and would introduce new transparency measures to improve oversight. In passing the bill, the House of Representatives also clarified that it intends the bill to be consistent with the Second Circuit’s ruling, so as to not weaken its findings.

The bill is no panacea and, as detailed below, would not ensure comprehensive reform. It still leaves open the possibility of large-scale data collection practices in the US under the Patriot Act. It does not constrain surveillance under Section 702 of the FISA Amendments Act nor Executive Order 12333, the primary legal authorities the government has used to justify mass surveillance of people outside US borders. And the bill does not address many modern surveillance capabilities, from mass cable tapping to use of malware, intercepting all mobile calls in a country, and compromising the security of mobile SIM cards and other equipment and services.

Nonetheless, passing a strong USA Freedom Act would be a long-overdue step in the right direction. It would show that Congress is willing and able to act to protect privacy and impose oversight over intelligence agencies in an age when technology makes ubiquitous surveillance possible.

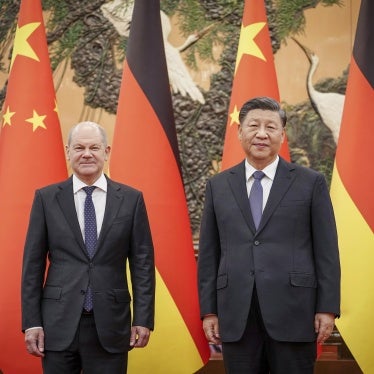

Passing this bill would also help shift the debate in the US and globally and would distance the United States from other countries that seek to make mass surveillance the norm. On a global level, other governments may already be emulating the NSA’s approach, fueling an environment of impunity for mass violations of privacy. In the last year, France, Turkey, Russia, and other countries have passed legislation to facilitate or expand large-scale surveillance.

If the USA Freedom Act passes, it would be the first time Congress has affirmatively restrained NSA activities since the attacks of September 11. Key supporters of the bill have vowed to take up reforms to other laws next, including Section 702 of the FISA Amendments Act.

The challenge human rights advocates face is that the very structure of US surveillance laws—and indeed, surveillance laws in many other countries—is premised on the notion that a country need only protect the privacy rights of those inside its territory, and is free to infringe on the privacy of those outside its borders. But in the digital age, with a government’s surveillance reach not limited by geography, neither should its obligation to respect privacy be so limited. The fundamental rights to privacy and free expression so sacred to Americans are no less precious to citizens of other countries, and no one can flourish under the threat, or the fact, of mass surveillance. Moreover, US surveillance of those outside US borders, without adequate privacy protections, may give other countries the green light to do the same to Americans.

Restructuring US law to protect people outside the US and reversing the tide of mass surveillance will not be easy. But Congress should show that the NSA can and should be reined in.

It is not too late to check the insidious creep of the surveillance state. “Collect it all” mass surveillance should end once and for all: we must make it an historical anomaly, not the new normal.

Background

What the USA Freedom Act does:

- Seeks to end bulk, indiscriminate collection of calling records under Section 215 of the Patriot Act and several other laws. Metadata collected under these provisions would have to be tied to a “specific selection term” that “specifically identifies an individual, account, or personal device.” To collect call records, the government would have to show that there is a reasonable articulable suspicion that the selection term is connected to terrorist activity. The bill imposes similar, though broader, limits on collection of other kinds of records.

- Reforms the secret Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) Court. It establishes a panel of experts to assist the court with novel or significant legal issues or technical matters, including by advocating for privacy and civil liberties. Under current practice, only the government is represented before the FISA court.

- Increases reporting and transparency. The bill requires the government to report on the use of surveillance authorities and publicly disclose unclassified FISA court opinions, or summaries of opinions, that involve significant interpretations of law, including novel interpretations of the term “significant selection term.” The bill would also codify the ability of technology companies to report on the number of surveillance orders received and the number of customer selectors targeted in aggregate ranges.

How the USA Freedom Act should be strengthened:

- Prevent large-scale and disproportionate collection of records. Although the bill requires security agencies to identify a “specific selection term” to serve as a basis for records collection, the definition of “specific selection term” is not narrow enough to prevent disproportionate collection that could harm the privacy of many people not connected to terrorism. In addition, the bill allows agencies to collect records of a “second hop” without any additional showing, allowing automatic collection of call records of those who have been in contact with the original number. Congress should narrow the definition of “specific selection term” to prevent large scale collection and remove the government’s ability to collect a “second hop” without some showing that such records are also linked to terrorism.

- Restore “super-minimization” procedures to limit retention of records. A prior version of the USA Freedom Act included “super-minimization” procedures that limited the government’s ability to retain data not shown to be related to terrorist activity and required deletion of such data. Congress should restore the prior version’s “super-minimization” procedures to limit retention of data.

- Strengthen court oversight and transparency measures. The bill’s FISA court reforms and transparency provisions are less robust than would have been required under a previous version of the bill introduced by Senator Patrick Leahy last year. If USA Freedom goes forward, it should include the stronger versions of these provisions from last year’s Senate bill.

- Remove provision that increases the maximum sentence for material support to terrorism. The US has misused material support charges to punish behavior that did not demonstrate an intent to support terrorism. Until the law is changed to avoid misapplication of such charges, this increase in penalties should be removed.

What the USA Freedom Act does not do:

- Does nothing to address mass surveillance under Section 702 of the FISA Amendments Act or Executive Order 12333. The majority of the NSA dragnet surveillance of people outside the US occurs under these two legal authorities. For example, the NSA compels Internet companies to provide access communications and personal data (PRISM) and requires telecom companies to assist with mass fiber optic cable tapping of traffic coming into the US (Upstream) under Section 702. The USA Freedom Act only addresses bulk records collection under the Patriot Act and certain other laws. Congress should next take up reforms to rein in mass surveillance under these legal authorities.

- Does not provide needed protections for whistleblowers who might reveal similar surveillance abuses in the future. President Obama has welcomed the current debate over privacy and surveillance in the digital age. This debate would not be possible without the work of whistleblowers like Edward Snowden and others who came before him. Yet existing laws and practices give would-be whistleblowers (especially those in the intelligence community) few internal ways to disclose governmental misconduct, no recourse when existing options are inaccessible or unresponsive, and no meaningful right to challenge official retaliation and defend themselves from criminal and civil liability.