The Zimbabwean finance minister, Tendai Biti, is coming to London this week to ask for a step-change in British aid for Zimbabwe. As a long-time opponent of President Mugabe, a human rights lawyer and the number two in the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), Biti is the right messenger, but is it the right message? Is aid to Zimbabwe's new power-sharing government what the country needs most right now?

Zimbabwe's economy is in a dreadful state. More than half the population depend for survival on food assistance from the UN. A major cholera outbreak recently killed 4,000 people. There's no money to fix the country's collapsed water system. Schools are closed for lack of money to pay teachers. For the same reason hospitals and health clinics are nearly empty of doctors, nurses, medicine and equipment. Unemployment stands at about 90%. In the face of this crisis the UK is giving about £50m in humanitarian aid a year to Zimbabwe and last week the government announced another £15m on top of that. The top-up was a sweetener to underline the UK's support for moderate voices like Biti in the power-sharing government of the MDC and Mugabe's Zanu-PF. But it also appeared to be an effort to head off requests from Zimbabwe for the resumption of more formal and potentially more generous government-to-government economic assistance.

At present UK humanitarian assistance to Zimbabwe is delivered entirely through UN agencies and NGOs. That's how it should be. Giving aid directly to an unreformed government apparatus in Harare risks perpetuating the causes of the crisis in Zimbabwe which UK foreign secretary David Miliband has correctly identified as "the misrule, abuse, neglect and corruption of the current Mugabe regime" Throughout the 1980s and 1990s British policymakers paid far too little attention to the abusive tactics by which Mugabe consolidated his power and repressed any serious opposition to his despotic rule, starting with the massacres in Matabeleland by the infamous Fifth Brigade of the Zimbabwean army in the mid-1980s.

Extraordinarily enough, UK political, economic and even military support continued to flow to Mugabe right up until the late 1990s, long after it was blindingly clear how abusive Mugabe's government really was. Eventually the arguments used to justify supporting Mugabe (and which continue to be used to justify support to repressive and corrupt leaders in Africa and elsewhere) simply ran out of credibility.

But it's possible that with formation of a power-sharing agreement those arguments - that the new government is "going in the right direction", that the current set-up is "the best opportunity there is" - might start making enough sense again for British ministers to consider resuming government-to-government assistance. They should think hard about that and resist repeating the mistakes of the past.

All the signs are that Mugabe remains fully committed to staying in power by whatever means possible. He agreed to the new power-sharing arrangements only under the greatest of external pressure and is doing his best to limit the power of the MDC in the new government. Mugabe and his loyalists remain fully in charge of the key security ministries, the army and police. Many of the 29,000 so-called "green bombers" or "war veterans", who perpetrated so much violence during last year's elections, remain on the government payroll.

Human rights activists, opposition supporters and dissident journalists are still regularly attacked, arbitrarily arrested and prosecuted in a court system that obeys Mugabe's bidding. Youth militia are still taking over the properties of commercial farmers. Crucially for potential donors, the finance ministry, under Biti, has no control over the central bank. By his own admission, Biti has been able to curtail the bank's influence for now only by abandoning the Zimbabwe dollar. The bank's governor, Gideon Gono, is responsible for funding Mugabe's repression - and he admitted recently that he had raided the accounts of foreign aid groups to pay government salaries.

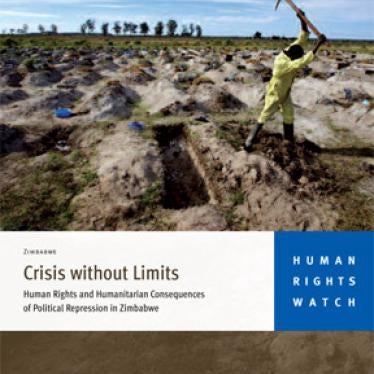

To cap it all, the Zimbabwe army has been doing what it does best in recent months: killing civilians in a brutal and secret operation launched last November to take control of diamond mines in southwest Zimbabwe. Human Rights Watch has documented the killing of more than 200 people in just one month at the Marange alluvial diamond mines, and the continuing implementation by the army and the police of a brutal regime of forced labour, torture and arbitrary arrest against thousands of others.

The aim of the operation is not to secure the revenue from the diamond mines for the new government's coffers - money that could be spent on addressing Zimbabwe's massive humanitarian crisis or on kickstarting the once profitable agricultural sector - but, our research found, to produce a new stream of revenue with which to line the pockets of Mugabe's loyalists and maintain the repressive and predatory infrastructure that keeps them in power.

There is much talk of reform in Zimbabwe but, as yet, no concrete action. The process of political change may have started but it is not irreversible. As long as Mugabe's nexus of repression and corruption remains in place, no amount of development assistance will help solve Zimbabwe's huge economic problems. And any economic aid to Harare from the UK or other donors will help to feed the crocodiles, just as surely as the blood-soaked profits of the Marange diamond mines.