MAE SOT, Thailand -- On Friday, millions of people will gather to celebrate universal values, national spirit, and the promise of progress in a country isolated for decades on the precipice of change. You might think of Aug. 8, 2008 in Beijing, but I'll be remembering Aug. 8, 1988, in Burma, the day that changed my life and that of countless compatriots.

Since eight is a lucky number in much of Asia, the Burmese people chose the auspicious 8.8.88 for their uprising, just as China decided to open the Olympic Games on 8.8.08. But while the eights still signal a celebration for many Chinese, for the Burmese they mark a massacre.

On Aug. 8, 1988, millions of Burmese marched throughout the country calling for an end to military rule, which had isolated and impoverished us since 1962. It was the culmination of months of unrest in Burma, and the army met us with merciless violence. Soldiers shot hundreds of protesters that day, and the army killed an estimated 3,000 people in the following weeks. The streets ran with blood but, back then, there were few images and no Internet to spread the news rapidly beyond our borders.

The outside world largely ignored events inside Burma, but for me there was no escape. As a student in Rangoon, I participated in many demonstrations and witnessed the brutal suppression by the riot police that killed and wounded so many. The regime also closed all schools, ending my education.

The first time I was arrested, in 1989, together with another student leader, Min Ko Naing, I managed to escape on the way to the interrogation. But in March 1990, the police picked me up at a student demonstration in Rangoon - we still hoped then that the approaching elections would change things - and a court sentenced me to three years in prison with hard labor. I spent more than seven of the next nine years in prison. I endured beatings, torture and long periods of solitary confinement in conditions not fit for animals. In 1999, the ongoing surveillance and intimidation by military intelligence made me concerned that any day I might return to prison. I fled to the Thai border, where I began working to inform the world about the brutal treatment of Burma's political dissidents.

Twenty years after our rulers crushed the rebellion, their prisons and labor camps hold more than 2,000 political activists. The Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi remains under house arrest, having spent much of the past two decades locked in her decaying house. Others, such as Burma's oldest political prisoner, the 78-year-old U Win Tin, remain incarcerated for their political writings and steadfast refusal to bow to the regime.

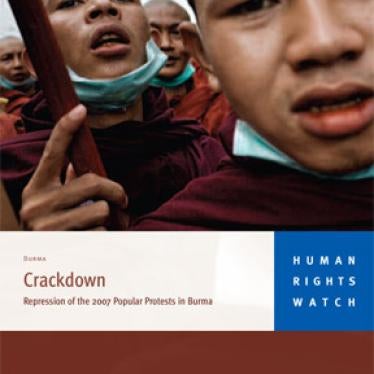

We got a reminder of the vast scale of repression with the bloody crackdown on peaceful protesters and monks in September 2007. Min Ko Naing (with whom I was arrested in 1989), was detained for his role in peaceful marches in Rangoon and remains in prison.

Few of us were shocked when the military-led government underlined its mockery of democracy by conducting a sham constitutional referendum amid the cyclone devastation wrought in May. The authorities even evicted cyclone survivors so that it could turn their shelters into polling stations, and then claimed a 98 percent turnout at a time when even emergency relief workers had yet to reach great swathes of the country.

Basic freedoms are routinely denied in Burma, with strict censorship, no right to assembly, and few avenues for expressing dissent. The army continues its brutal pacification of ethnic minority areas, routinely committing atrocities.

International efforts to engage the military government have floundered because of the regime's skill in pitting the countries who wish to trade and exploit Burma's natural wealth against those that want to isolate, punish and sanction the regime. Burma's generals seek to bypass Western sanctions, including new financial sanctions, by doing business with Asia-based companies and banks.

It's no surprise to me that Beijing would ignore the 1988 anniversary: China is a key trading partner and Burma's most important diplomatic supporter. Beijing continues to sell weapons to the Burmese military and train its soldiers, and enjoys access to Burma's lucrative gas fields and trade routes to the Indian Ocean. The tight relationship has entrenched military rule and left the regime secure in its belief that its superpower sponsor will subscribe to "national interests" and oppose progressive reform in Burma.

The world will no doubt mark Aug. 8 as a sporting celebration, but many Burmese will silently remember 1988. They do not deserve to wait another 20 years for the freedoms they demanded in 1988 and in 2007, for the reforms they long for every moment they survive under military rule.

Ko Bo Kyi is joint secretary of the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners in Burma and a winner of the 2008 Human Rights Watch Defender Award.