Julie was a graduate student at the University of Chicago when, in 2007, she was raped by a man she had been introduced to that night as a friend's new boyfriend. They were at a bar, and he was "acting weird toward me. He kept touching me and I kept pushing him away." The man's behavior attracted the attention of the club's manager and bouncer, who kicked him out.

Later that night, as Julie slept on her friend's couch, the boyfriend entered the apartment and raped her. Julie reported the rape to the police and went to a hospital for a forensic examination to collect DNA and other evidence from her body. She thought her rapist would be arrested.

Every year in the United States, more than 200,000 people report to the police that they have been raped. Many are asked to submit to the collection of DNA evidence from their bodies, which is stored in a small package called a rape kit. It is an invasive and sometimes traumatic process that takes four to six hours. But the potential benefits are enormous: testing the DNA evidence can identify an unknown rapist, confirm the identity of a known assailant, corroborate the victim's account, and exonerate innocent suspects. When a victim undergoes the examination to collect a rape kit, both she and the public reasonably assume that the kit will be tested. But all too often, that is not the case.

Following media reports in 2003 that the Chicago Police Department had 1,500 untested rape kits in storage, the department promised to send every rape kit to the Illinois State Police for testing. But stories from victims raped in Chicago since then raise disturbing questions about whether this promise is being kept. The police are refusing to answer those questions.

While we believe that Chicago sends every rape kit to the state crime lab, there are serious questions about what happens then. In response to a public records request, the state police tracked the number of DNA sexual assault cases sent to them by the Chicago police and the number where DNA testing actually occurred. In 2007, of 835 cases sent, only 388 were tested. Of the 1,211 cases sent in 2008, 685 were tested. The state police told us that rape kits from the Chicago police were not tested in cases where the police determined the reported rape was "unfounded" (in other words, did not happen) or state's attorney decides to close the case-cases like Julie's

When a victim undergoes the examination to collect a rape kit, both she and the public reasonably assume that the kit will be tested. For months after she was raped, Julie repeatedly called the investigating officer in her case, asking about the status of her rape kit. Her calls went unreturned.

In 2008, she was contacted by the state's attorney's office and told her case had been closed. Julie asked the prosecutor if the police had interviewed the bar manager and bouncer who witnessed her assailant's behavior had been interviewed. The prosecutor said no. Julie asked if her rape kit had been tested. The prosecutor said no.

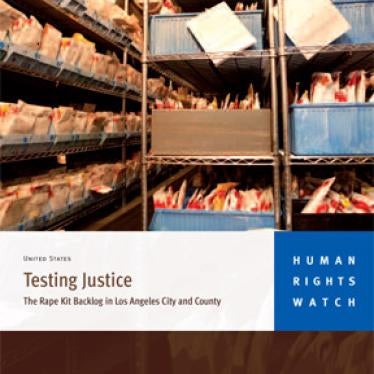

Human Rights Watch has been tracking the issue of whether rape kits are actually tested or just sit in police storage around the country. In Los Angeles alone, we found 12,500 untested kits. Both the city and the county have promised to test those kits. Testing all the kits can reveal valuable information that could change a prosecutor's mind, though. When New York started testing all its kits, not only did the arrest rate go up, but the prosecution rate also skyrocketed.

The state police said that untested rape kits connected to closed cases are returned to the requesting agency. The Chicago Police Department has denied our public records request for the number that may have been returned with the startling response that, "We do not keep information on rape kits." Repeated requests to speak with principals at the Chicago Police Department have been met with silence.

So, what happened to Julie's kit, and all the other kits like it? If the Chicago Police Department has a good answer, it isn't telling victims like Julie, and it isn't telling us. If the department has in place a system that ensures all rape kits are tested, it should want to share information about its success. If, on the other hand, there are untested rape kits accumulating in police storage facilities, the victims in those crimes, and the public have a right to an explanation.

Untested rape kits, and closed cases, can mean lost justice for some rape victims, and lost opportunity for a Chicago community that cares about preventing sexual violence.